Abstract

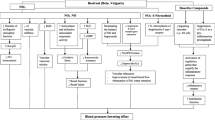

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a public health concern, and the third cause of death worldwide. Several epidemiological studies and experimental approaches have demonstrated that consumption of polyphenol-enriched fruits and vegetables can promote cardioprotection. Thus, diet plays a key role in CVD development and/or prevention. Physiological β-adrenergic stimulation promotes beneficial inotropic effects by increasing heart rate, contractility and relaxation speed of cardiomyocytes. Nevertheless, chronic activation of β-adrenergic receptors can cause arrhythmias, oxidative stress and cell death. Herein the cardioprotective effect of human metabolites derived from polyphenols present in berries was assessed in cardiomyocytes, in response to chronic β-adrenergic stimulation, to disclose some of the underlying molecular mechanisms. Ventricular cardiomyocytes derived from neonate rats were treated with three human bioavailable phenolic metabolites found in circulating human plasma, following berries’ ingestion (catechol-O-sulphate, pyrogallol-O-sulphate, and 1-methylpyrogallol-O-sulphate). The experimental conditions mimic the physiological concentrations and circulating time of these metabolites in the human plasma (2 h). Cardiomyocytes were then challenged with the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (ISO) for 24 h. The presence of phenolic metabolites limited ISO-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress. Likewise, phenolic metabolites increased cell beating rate and synchronized cardiomyocyte beating population, following prolonged β-adrenergic receptor activation. Finally, phenolic metabolites also prevented ISO-increased activation of PKA–cAMP pathway, modulating Ca2+ signalling and rescuing cells from an arrhythmogenic Ca2+ transients’ phenotype. Unexpected cardioprotective properties of the recently identified human-circulating berry-derived polyphenol metabolites were identified. These metabolites modulate cardiomyocyte beating and Ca2+ transients following β-adrenergic prolonged stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- β-AR:

-

β-Adrenergic receptors

- BDP:

-

Berry-derived polyphenols

- CaMKII:

-

Calcium calmodulin-dependent kinase II

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- ISO:

-

Isoproterenol

- PKA:

-

cAMP-dependent protein kinase A

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxidative species

- RyR:

-

Ryanodine receptors

- SR:

-

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

- SERCA:

-

Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase

- GPCRs:

-

G protein-coupled receptors

References

Baker, A. J. (2014). Adrenergic signaling in heart failure: A balance of toxic and protective effects. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology, 466(6), 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-014-1491-5.

Bers, D. M. (2008). Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annual Review of Physiology, 70, 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455.

Najafi, A., Sequeira, V., Kuster, D. W., & van der Velden, J. (2016). β-Adrenergic receptor signalling and its functional consequences in the diseased heart. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 46(4), 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12598.

El-Armouche, A., & Eschenhagen, T. (2009). β-Adrenergic stimulation and myocardial function in the failing heart. Heart Failure Reviews, 14(4), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-008-9132-8.

Bers, D. M. (2002). Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature, 415(6868), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/415198a.

Andersson, D. C., Fauconnier, J., Yamada, T., Lacampagne, A., Zhang, S.-J., Katz, A., et al. (2011). Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species contributes to the β-adrenergic stimulation of mouse cardiomycytes. The Journal of Physiology, 589(7), 1791–1801. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202838.

Curran, J., Hinton, M. J., Rı, E., Bers, D. M., & Shannon, T. R. (2007). Beta-adrenergic enhancement of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak in cardiac myocytes is mediated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Circulation Research, 100(3), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.0000258172.74570.e6.

Bovo, E., Lipsius, S. L., & Zima, A. V. (2012). Reactive oxygen species contribute to the development of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves during β-adrenergic receptor stimulation in rabbit cardiomyocytes. The Journal of Physiology, 590(14), 3291–3304. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230748.

Bovo, E., Mazurek, S. R., De Tombe, P. P., & Zima, A. V. (2015). Increased energy demand during adrenergic receptor stimulation contributes to Ca2+ wave generation. Biophysical Journal, 109(8), 1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.002.

Branco, A. F., Sampaio, S. F., Wieckowski, M. R., Sardão, V. A., & Oliveira, P. J. (2013). Mitochondrial disruption occurs downstream from β-adrenergic overactivation by isoproterenol in differentiated, but not undifferentiated H9c2 cardiomyoblasts: Differential activation of stress and survival pathways. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, 45(11), 2379–2391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2013.08.006.

Branco, A. F., Pereira, S. L., & Oliveira, P. J. (2011). Isoproterenol cytotoxicity is dependent on the differentiation state of the cardiomyoblast H9c2 cell line. Cardiovascular Toxicology, 11, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-011-9111-5.

Mendis, S., Puska, P., Norrving, B. (Eds.). (2011). Global Atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization.

Arts, I. C. W., & Hollman, P. C. H. (2005). Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies 1–4. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 81(1), 317S–325S.

Vauzour, D., Rodriguez-Mateos, A., Corona, G., Oruna-Concha, M. J., & Spencer, J. P. E. (2010). Polyphenols and human health: Prevention of disease and mechanisms of action. Nutrients, 2(11), 1106–1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2111106.

Johnson, S. A., Figueroa, A., Navaei, N., Wong, A., Kalfon, R., Ormsbee, L. T., et al. (2015). Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(3), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.001.

Watson, R. R., Victor, P., & Zibadi, S. (2014). Polyphenols in human health and disease. San Diego: Academic Press.

Du, G., Sun, L., Zhao, R., Du, L., Song, J., Zhang, L., et al. (2016). Polyphenols: Potential source of drugs for the treatment of ischaemic heart disease. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 162, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.04.008.

Dolinsky, V. W., Chakrabarti, S., Pereira, T. J., Oka, T., Levasseur, J., Beker, D., et al. (2013). Resveratrol prevents hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in hypertensive rats and mice. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 1832(10), 1723–1733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.018.

Manach, C. (2004). Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 79(5), 727–747.

Rodriguez-Mateos, A., Heiss, C., Borges, G., & Crozier, A. (2014). Berry (poly)phenols and cardiovascular health. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62(18), 3842–3851. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf403757g.

Pimpão, R. C., Dew, T., Figueira, M. E., Mcdougall, G. J., Stewart, D., Ferreira, R. B., et al. (2014). Urinary metabolite profiling identifies novel colonic metabolites and conjugates of phenolics in healthy volunteers. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 58(7), 1414–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201300822.

Pimpão, R. C., Ventura, M. R., Ferreira, R. B., Williamson, G., & Santos, C. N. (2015). Phenolic sulfates as new and highly abundant metabolites in human plasma after ingestion of a mixed berry fruit purée. The British journal of nutrition, 113(3), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514003511.

Nicklas, W., Baneux, P., Boot, R., Decelle, T., Deeny, A. A., Fumanelli, M., et al. (2002). Recommendations for the health monitoring of rodent and rabbit colonies in breeding and experimental units. Laboratory Animals, 36(1), 20–42. https://doi.org/10.1258/0023677021911740.

Louch, W. E., Sheehan, K. A., & Wolska, B. M. (2011). Methods in cardiomyocyte isolation, culture, and gene transfer. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 51(3), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.012.

Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., et al. (2012). Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9(7), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019.

Willis, B. C., Salazar-Cantú, A., Silva-Platas, C., Fernández-Sada, E., Villegas, C., Rios-Argaiz, E., et al. (2015). Impaired oxidative metabolism and calcium mishandling underlie cardiac dysfunction in a rat model of post-acute isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 308(5), H467–H477. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00734.2013.

Moore, M. J., Kanter, J. R., Jones, K. C., & Taylor, S. S. (2002). Phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(49), 47878–47884. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M204970200.

Song, Y.-H., Choi, E., Park, S.-H., Lee, S.-H., Cho, H., Ho, W.-K., et al. (2011). Sustained CaMKII activity mediates transient oxidative stress-induced long-term facilitation of L-type Ca2+ current in cardiomyocytes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 51(9), 1708–1716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.022.

Mustroph, J., Neef, S., & Maier, L. S. (2017). CaMKII as a target for arrhythmia suppression. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.006.

Dewenter, M., Neef, S., Vettel, C., Lämmle, S., Beushausen, C., Zelarayan, L. C., et al. (2017). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity persists during chronic β-adrenoceptor blockade in experimental and human heart failure. Circulation: Heart Failure, 10(5), e003840. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.003840.

Aratyn-Schaus, Y., Pasqualini, F. S., Yuan, H., McCain, M. L., Ye, G. J. C., Sheehy, S. P., et al. (2016). Coupling primary and stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in an in vitro model of cardiac cell therapy. The Journal of Cell Biology, 212(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201508026.

Bito, V., Sipido, K. R., & Macquaide, N. (2015). Basic methods for monitoring intracellular Ca2+ in cardiac myocytes using Fluo-3. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols, 2015(4), 392–397. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot076950.

Dries, E., Santiago, D. J., Johnson, D. M., Gilbert, G., Holemans, P., Korte, S. M., et al. (2016). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and nitric oxide synthase 1 dependent modulation of ryanodine receptors during β-adrenergic stimulation is restricted to the dyadic cleft. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689–1699. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Vanni, S., Neri, M., Tavernelli, I., & Rothlisberger, U. (2011). Predicting novel binding modes of agonists to β adrenergic receptors using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS Computational Biology, 7(1), e1001053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001053.

Lefkowitz, R. J., & Williams, L. T. (1977). Catecholamine binding to the beta-adrenergic receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 74(2), 515–519.

Deng, H., & Fang, Y. (2013). The three catecholics benserazide, catechol and pyrogallol are GPR35 agonists. Pharmaceuticals, 6(12), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph6040500.

Ambrosio, C., Molinari, P., Cotecchia, S., & Costa, T. (2000). Catechol-binding serines of beta(2)-adrenergic receptors control the equilibrium between active and inactive receptor states. Molecular Pharmacology, 57(1), 198–210

Moniotte, S., Kobzik, L., Feron, O., Trochu, J.-N., Gauthier, C., & Balligand, J.-L. (2001). Upregulation of 3-adrenoceptors and altered contractile response to inotropic amines in human failing myocardium. Circulation, 103(12), 1649–1655. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.12.1649.

Ufer, C., & Germack, R. (2009). Cross-regulation between β 1- and β 3-adrenoceptors following chronic β-adrenergic stimulation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 158(1), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00328.x.

Lohse, M. J., Engelhardt, S., Danner, S., & Böhm, M. (1996). Mechanisms of b-adrenergic receptor desensitization: From molecular biology to heart failure. Basic Research in Cardiology, 91(S1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00795359.

Hausdorff, W. P., Caron, M. G., & Lefkowitz, R. J. (1990). Turning off the signal: Desensitization of beta-adrenergic receptor function. The FASEB Journal, 4(11), 2881–2889. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.4.11.2165947.

Wallace, C. H. R., Baczkó, I., Jones, L., Fercho, M., & Light, P. E. (2006). Inhibition of cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels by grape polyphenols. British Journal of Pharmacology, 149(6), 657–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0706897.

Belevych, A. E. (2002). Genistein inhibits cardiac L-Type Ca2+ channel activity by a tyrosine kinase-independent mechanism. Molecular Pharmacology, 62(3), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.62.3.554.

Obayashi, K., Horie, M., Washizuka, T., Nishimoto, T., & Sasayama, S. (1999). On the mechanism of genistein-induced activation of protein kinase A-dependent Cl—Conductance in cardiac myocytes. Pflügers Archiv European Journal of Physiologygers Archiv European Journal of Physiology, 438(3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004240050909.

Hool, L. C., Middleton, L. M., & Harvey, R. D. (1998). Genistein increases the sensitivity of cardiac ion channels to beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Circulation Research, 83(1), 33–42.

LIEW, R., Macleod, K. T., & COLLINS, P. (2003). Novel stimulatory actions of the phytoestrogen genistein: Effects on the gain of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. The FASEB Journal, 17(10), 1307–1309. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.02-0760fje.

Bode, A. M., & Dong, Z. (2015). Toxic phytochemicals and their potential risks for human cancer. Cancer Prevention Research, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0160.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pedro Sampaio, from Cilia Regulation and Disease lab, CEDOC, for technical support regarding the cardiomyocyte beating measurement.

Funding

The present work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT, Portugal) [ANR-FCT/BEX-BCM/0001/2013], iNOVA4Health Unit (UID/Multi/04462/2013), the Agence National de la Recherche (France) [Grant ANR-13-ISV1-0001-01] and by the laBex LERMIT. Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia provided individual financial support to AG (SFRH/BD/103155/2014), HLAV (IF/00185/2012) and CNS (IF/01097/2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Shazina Saeed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12012_2018_9485_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 1 Schematic representation of the different phenolic metabolites used. The compounds were present in the human plasma in different concentrations: catechol-O-sulphate: 12 µM; pyrogallol-O-sulphate: 6 µM; and 1-methylpyrogallol-O-sulphate: 3 µM. (TIF 439 KB)

12012_2018_9485_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 2 Cell Viability. Cell viability was detected using propidium iodide, of differentiated H9c2 cells, treated with phenolic metabolites for 2 h and exposed to ISO for 48 h. Data are mean ± SD. ****P < 0.0001 versus Control and ####P < 0.0001 versus ISO (ISO: Isoproterenol). (TIF 482 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dias-Pedroso, D., Guerra, J., Gomes, A. et al. Phenolic Metabolites Modulate Cardiomyocyte Beating in Response to Isoproterenol. Cardiovasc Toxicol 19, 156–167 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-018-9485-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-018-9485-8