Abstract

Background

Little is known about what factors are important to older adults when deciding whether to agree with a recommendation to deprescribe.

Objective

To explore the extent to which medication type and rationale for potential discontinuation influence older adults’ acceptance of deprescribing.

Design

Cross-sectional 2 (drug: lansoprazole — treat indigestion; simvastatin — prevent cardiovascular disease) by 3 (deprescribing rationale: lack of benefit; potential for harm; both) experimental design.

Participants

Online panelists aged ≥65 years from Australia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Interventions

Participants were presented with a hypothetical patient experiencing polypharmacy whose PCP discussed stopping a medication. We randomized participants to receive one of six vignettes.

Main Measures

We measured agreement with deprescribing (6-point Likert scale, “Strongly disagree (1)” and “Strongly agree (6)”) for the hypothetical patient as the primary outcome. We also measured participants’ personality traits, perceptions of risk and uncertainty, and attitudes towards polypharmacy and deprescribing.

Key Results

Among 5311 participants (93.3% completion rate), the mean (M) agreement with deprescribing for the hypothetical patient was 4.71 (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.67, 4.75). Participants reported higher agreement with stopping lansoprazole (n=2656) (M=4.90, 95% CI: 4.85, 4.95) compared to simvastatin (n=2655) (M=4.53, 95% CI: 4.47, 4.58), P<.001. Participants who received the combination rationale (n=1786) reported higher agreement with deprescribing (M=4.83, 95% CI: 4.76, 4.89) compared to those who received the rationales on lack of benefit (n=1755) (M=4.66, 95% CI: 4.60, 4.73) or potential for harm (n=1770) (M=4.65, 95% CI 4.58, 4.72). In adjusted regression analyses (n=5062), participants with a higher desire to engage in health promotion behaviors (b=0.08, 95% CI 0.02, 0.13) or need for certainty (b=0.12, 95% CI 0.04, 0.20) reported higher agreement with deprescribing.

Conclusions

Older adults across four countries were accepting of deprescribing in the setting of polypharmacy. The medication type and rationale for discontinuation were important factors in the decision-making process.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04676282, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04676282?term=vordenberg&draw=2&rank=1

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of chronic medications in older adults can have diminishing benefit and become potentially unsafe over time due to factors including physiological changes associated with aging, the accumulation of multiple chronic health conditions leading to more medications, and drug-drug and drug-disease interactions.1, 2 Globally, up to 50% of adults aged 65 years and above take one or more inappropriate medications, which has been associated with functional decline, reduced quality of life, and increased healthcare costs.3

One important approach that may reduce inappropriate or unnecessary medication use among older adults is deprescribing, the process of tapering or stopping medications lacking benefit or potentially causing harm.4 Existing efforts have mostly focused on providing guidance to clinicians about the deprescribing process but have less often focused on patients.5,6,7,8,9,10 Involving the patient in deprescribing decisions is critical to ensuring that the plan aligns with the patient’s preferences and goals.11,12,13,14,15

Existing literature on patients’ perspectives on deprescribing shows mixed results.16, 17 Many older adults have expressed interest in stopping unnecessary medications while at the same time preferring to continue their current medications18, citing concerns about what will occur during and after the deprescribing process (e.g., withdrawal effects, recurrence of symptoms).11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Better understanding of what factors influence older adults in deprescribing decisions is critical. We sought to address this knowledge gap using a vignette-based experiment. We explored the extent to which type of medication (i.e., preventive vs. symptomatic treatment) and rationale for potential discontinuation (i.e., lack of benefit, potential for harm, or both) influenced older adults’ agreement with a recommendation from the primary care physician to deprescribe a medication for a hypothetical patient.

Methods

We conducted a vignette-based online experiment using hypothetical vignettes with older adults recruited from Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), and the Netherlands. We chose these countries because they have markedly different healthcare systems and our research team has experience with the healthcare systems within these countries. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) and registered as a clinical trial at Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT04676282.

Study Design and Sample

Participants were demographically diverse samples of older adults aged 65 years and above recruited through a panel of Internet users administered by Qualtrics Research Panels (Provo, UT) from December 2020 to March 2021.24 Qualtrics used various opt-in methods to assemble their panel. For our project, a random subset of eligible panelists were invited to participate according to our study’s pre-specified sample size and demographic distributions. We focused our power calculation on how three different rationales for deprescribing would impact agreement with a recommendation for deprescribing from a physician. We determined that a sample size of 1200 for each country would allow us to detect a 10% difference in level of agreement with a dichotomous primary outcome measure with power=0.80 and α=0.05 for a variable with 3 levels. We included quotas to ensure equal numbers of participants from each country and 50% of participants from each country would be female. For the US participants, we established quotas based on race and ethnicity that aligned with the national data (18% Hispanic, 15% African American, 5% Asian, 62% White/Other race/ethnicity). The sampling algorithm continued to invite panelists to complete the survey until all quotas were achieved. Strategies such as checking IP addresses, digital fingerprint technology, and deduplication technology were used to prevent multiple responses by one participant. To avoid self-selection bias, survey invitations did not include the study topic. The survey was administered in English for the US, UK, and Australia, and translated and administered in Dutch for the Netherlands.

All data were collected anonymously using Qualtrics software (Provo, UT). Participants were compensated based on the conditions of their panel agreement.

Intervention

We created a vignette about “Mrs. EF,” a 76-year-old who uses 11 medications to manage her multiple health conditions based on previous work of Todd et al. (Text box).16, 18 We sought to bring Mrs. EF to life by including details about her medical history, social history, and general attitudes and beliefs about her doctor and medications.20 By including her medication list as a figure in the survey, we aimed to better communicate the potential burden of her current medication regimen. After displaying this information, we asked participants to imagine that Mrs. EF was going to her primary care provider (PCP) for a routine visit.

Text Box Hypothetical vignette displayed to participants in online survey

Mrs. EF is a 76-year-old female who has multiple health conditions including:

-

Atrial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat)

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (chronic breathing problem)

-

Constipation

-

Depression

-

High blood pressure

-

High cholesterol

-

History of blood clots

-

Indigestion (upset stomach)

-

Prevention of brittle bones (osteoporosis)

Mrs. EF has regularly seen her primary care provider (PCP) for the past 10 years to help manage her health. A PCP is a doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant who sees people for common medical conditions. She trusts her PCP.

Over the years, her PCP has prescribed 11 medications. She takes all of the medications according to the directions (see picture below).

Mrs. EF believes that is a good idea to take medications if they benefit her health, even if the benefit is very small. However, Mrs. EF also doesn’t really like having to take medications.

She has had a number of problems including feeling tired, having constipation, and occasionally feeling dizzy. She talked with her PCP about this in the past and it was unclear which, if any, medication is causing these problems.

Mrs. EF’s husband was diagnosed with cancer several years ago and he recently had a stroke. She has been very busy taking care of him which has made it more difficult for her to manage her health conditions through lifestyle changes, such as eating healthy foods and being physically active. Taking care of her husband has made her want to take care of her own health even more than in the past.

Mrs. EF is at a routine visit with her PCP today. The following conversation takes place during the visit:

PCP: “I was looking at your list of medication and I would like to talk with you about potentially making a change.”

Mrs. EF: “What type of change?”

PCP: “I know that you have been taking [simvastatin/lansoprazole] once a day for several years. We talked about how this medication would lower your cholesterol and, in turn, help to prevent heart disease and strokes.”

Mrs. EF: “Yes, I make sure to take [simvastatin/lansoprazole] every day. I never skip a dose because I know it is important.”

PCP: “That’s great that you have been taking it every day. I am glad that you have [never had a stroke/not been having any indigestion]. However [rationale related to either lack of benefit, potential for harm, or a combination of lack of benefit and potential for harm – see Fig. 1]”

Based on what you have read so far, please choose how much you agree or disagree with the following statement:

I think that Mrs. EF should follow her PCPs recommendation and stop taking [simvastatin/lansoprazole]. (6-point Likert scale; 1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree)

The vignette-based online experiment examined the extent to which type of medication (i.e., preventive vs. symptomatic treatment) and rationale for potential discontinuation (i.e., lack of benefit, potential for harm, or both) influenced participants’ agreement with a recommendation from Ms. EF’s PCP for her to deprescribe a medication. We programmed the survey to randomize participants to receive one of six vignettes using a 2 (lansoprazole, to treat indigestion; simvastatin, to prevent heart disease and stroke) by 3 (lack of benefit; potential for harm; or combination of both) experimental design (Fig. 1). Randomization was set such that each vignette was displayed an equal number of times. The rationale for selecting these medications in our vignette was both statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) and proton pump inhibitors are frequent targets of deprescribing.25,26,27,28,29

The survey was refined based on feedback from patient and public engagement groups. We (JJ and a bilingual medical student) identified existing Dutch versions of validated scales and translated the rest of the survey into Dutch. We made minor modifications to the scenario wording to align with the context of the different countries (e.g., changing PCP to General Practitioner for participants outside the US). We piloted the survey with 50 participants per country through Qualtrics and made revisions to improve survey length.

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome

-

1.

Agreement with deprescribing recommendation: The participants’ attitude towards deprescribing as measured by the extent of agreement with the statement, “I think that Mrs. EF should follow the doctor’s recommendation and stop taking [medication],” on a 6-point Likert scale with “Strongly disagree (1)” and “Strongly agree (6)” as the scale anchors.

Covariates

-

1.

Personality traits

-

a.

Preferences for more or less medical care: The single-item Medical Maximizer-Minimizer measure (MM1) measured preferences for seeking medical care, ranging from “I strongly lean towards waiting and seeing (1)” to “I strongly lean towards taking action (6).”30

-

b.

Beliefs about medicines: The 18-item Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) measured levels of agreement with medication use in general, the necessity of medications, and concerns about medications on a 5-point scale, with “Strongly disagree (1)” to “Strongly agree (5)” as the scale anchors.31, 32

-

c.

Health promotion/prevention: The 12-item Health Regulatory Focus Scale (HRFS) measured desire to engage in actions to promote health or prevent poor health, with “Not at all (1)” to “A great extent (7)” as the scale anchors.33

-

d.

Attitude towards uncertainty: The 8-item Attitude towards Uncertainty scale measured individuals’ comfort level regarding uncertainty, with “Strongly disagree (1)” and “Strongly agree (5)” as the scale anchors.34

-

a.

-

2.

Health literacy: Participants’ confidence filling out medical forms was measured using a single item with responses ranging from “Not at all (1)” to “Excellent (5).”39, 40

-

3.

Subjective health status: Participants’ perceptions of their health as measured by their response to the question “In general, how would you rate your health today?” with responses ranging from “Poor (1)” to “Excellent (5).”38

-

4.

Personal experience with medication: Participants’ self-report of taking a medication in the same therapeutic class as the medication presented in the scenario (i.e., statin or proton pump inhibitor) with responses of “Current,” “Previous use,” or “Never used.”

-

5.

Risk perceptions: We adapted the 6-item Tripartite Model of Risk Perception (TRIRISK) scale that measures Deliberative, Affective, and Experiential risk perceptions with questions such as, “How likely do you think it is that Mrs. EF’s heart health will worsen at some point in the future with simvastatin?” with “Very unlikely (1)” and “Very likely (7)” as the scale anchors.36

-

6.

Attitudes towards medications

-

a.

Stopping a medication (positive, beneficial, not harmful): These three adapted single-item measures on a 10-point scale: “I think that Mrs. EF stopping [medication] would be…” “Very positive (1)” to “Very negative (10),” “Very beneficial (1)” to “Not beneficial (10),” “Not harmful (1)” to “Very harmful (10)” as the scale anchors.35, 36

-

b.

Number of medications: Adapted single-item measure: “Mrs. EF takes 11 medicines. How positive or negative do you feel towards the number of medicines that Mrs. EF takes?” with “Very negative (1)” and “Very positive (10)” as the scale anchors.37

-

a.

Demographics and Medication Use

Country, age, gender, and education were measured. Number of medications taken (prescription, non-prescription, and/or dietary supplements) and amount of support needed for managing their medications was collected. Participants were also asked to “thoughtfully provide your best answers to each question” and individuals who selected “I will not provide my best answers” or “I can’t promise either way” were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics and conducted independent samples t-tests and ANOVAs to compare group means. We used ordered logistic regression to examine factors associated with agreement with stopping medications using the 6-point Likert scale and included experimental factors (drug in scenario, rationale for stopping medication), personality traits, participant characteristics (i.e., county of residence, age, gender, education, health literacy, health status, and personal use of the medication), risk perceptions, attitudes towards deprescribing, and positive attitudes towards polypharmacy. We used a statistical significance level of P<.017 to account for the number of similar analyses (P<0.05 divided by 3). Case-wise deletion was used for missing data for the ordered logistic regression analysis. All analyses were conducted with Stata, version Stata SE 16.0 (StataCorp). We reported our study according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist.41

Results

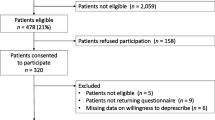

A total of 5693 individuals started the survey. We excluded participants who were younger than 65 years or did not reside in a participating country (n=301) and 81 participants who did not agree to give high-quality answers. The final analytical sample comprised 5311 participants (93.3% completion rate)

The mean age of participants was 71.4 years (SD 4.9 years) (Table 1).

Most participants reported earning less than a Bachelor’s degree (65.2%), being in good health (43.0%), and being extremely confident filling out medical forms (44.2%). Participants reported taking an average of 7.0 medications (SD 10.9).

The mean (M) level of agreement with stopping the medication was 4.71 (on a 6-point Likert scale, 95% CI: 4.67, 4.75), but participants reported higher agreement with stopping lansoprazole (M=4.90, 95% CI: 4.85, 4.95) compared to simvastatin (M=4.53, 95% CI: 4.47, 4.58), P<.001 (Fig. 2).

Participants who received the combination rationale reported higher agreement with stopping the medication (M=4.83, 95% CI: 4.76, 4.89) compared to those who received the rationales only related to lack of benefit (M=4.66, CI: 4.60, 4.73) or potential for harm (M=4.65, 95% CI 4.58, 4.72). Willingness to stop lansoprazole remained higher than simvastatin (b=0.24, 95% CI 0.12, 0.35) when controlling for covariates (Table 3).

Participants who were given the deprescribing rationale about the medication’s lack of benefit in combination with a potential for harm had higher agreement that Mrs. EF should follow her PCP’s recommendation to deprescribe than with either rationale alone (Table 2), F(2, 5295)=8.93, P<0.001. However, when controlling for covariates, participants had higher agreement with the recommendation to deprescribe when the potential for harm was provided for either medication (b=0.16, 95% CI 0.02, 0.29), as opposed to the lack of benefit or a combination of lack of benefit and potential for harm.

We found that participants across all four countries reported high level of agreement with recommendation for deprescribing (Table 2). In unadjusted analyses, participants in Australia and the US were more willing to agree with the recommendation for deprescribing (Appendix 2a and 2b), F(3, 5294)=10.24, P<0.001. However, participants in the UK reported increased agreement with stopping the medications (Table 3) when controlling for covariates.

Participants frequently reported personal experience currently or previously taking a statin (53.2%) or proton pump inhibitor (40.5%). In adjusted analyses, individuals who reported previously taking the therapeutic class of medication presented in the scenario reported higher agreement with deprescribing compared with those currently taking the medication (b=0.23, 95% CI 0.04, 0.42). There was no difference in agreement with deprescribing among participants who currently or never took the medication.

There were several attitudes towards medications and risk perceptions that were predictive of less agreement with stopping the medication (Table 3). These included feeling that stopping a medication would be negative (b=−0.35, 95% CI −0.39, −0.30), not beneficial (b=−0.41, 95% CI −0.45, −0.36), or harmful (b=−0.10, 95% CI −0.13, −0.07); positive perceptions of taking 11 medications daily (b=−0.04, 95% CI −0.07, −0.01) or feeling anxious or worried that Mrs. EF’s health would worsen in the future without the medication (b=−0.23, 95% CI −0.30, −0.16) (Affective risk perceptions).

Finally, for the personality traits, individuals with a higher desire to engage in health promotion behaviors (b=0.08, 95% CI 0.02, 0.13) or a higher need for certainty (b=0.12, 95% CI 0.04, 0.20) reported higher agreement with stopping the medication. There were no statistically significant associations between agreement with deprescribing and medical maximizing, beliefs about medicines questionnaire, and the desire to engage in actions to prevent poor health.

Discussion

Deprescribing of inappropriate medications is increasingly recognized as an important strategy for optimizing medication use among older adults.42 However, several systematic reviews have shown there is resistance to deprescribing in clinical practice from both patients and clinicians.17, 43, 44 Our findings, from the largest international deprescribing survey to date, show that older adults were significantly more accepting of a recommendation to stop a medication to treat a symptom that can be self-monitored compared to a medication to prevent future health problems. This may have been due to the heightened perceived importance of the medication itself (a medication for the heart), concerns about having a cardiovascular event if the medication was stopped, and the lack of ability to monitor the impact of a preventive medication.

In contrast, Vordenberg et al. previously reported that adults 65 years and older in the US reported similar rates of concern about stopping medications that differed based on risk, regulatory status, and indication for discontinuation.20 However, the study presented one medication at a time without patient-related information.20

When discussing deprescribing, a clinician may focus on the balance of benefits and harms, quality of life, diminishing returns, and uncertainty of evidence for specific medications.45 However, it is not feasible to include all of these topics in a brief medical visit. A recent discrete choice experiment study found that Danish general practitioners prefer a brief, as opposed to none or detailed, discussion with patients about statin deprescribing.46 In systematic reviews, Hoffmann et al. identified that patients and clinicians inaccurately perceive the potential benefits of treatments (overestimate) and the harms (underestimate) which could influence deprescribing.47, 48 It has been posited that the benefit of medicines is often taken for granted so informing individuals that their medicine lacks benefit may not resonate or be convincing enough to counteract the assumption that medicines are beneficial.31 Interestingly, our findings indicate that older adults across four diverse countries are more likely to agree with stopping a medication when they are presented with information about the potential harm of the medication. This suggests that if an individual is presented with the potential for harm of a medication, this may challenge strong beliefs about the potential benefits of medicines in general and raise concerns, which could in turn create an opportunity to deprescribe. Our work suggests that PCPs should focus on potential harms when discussing deprescribing recommendations with patients.

Research suggests that a person’s experience with deprescribing in the past can influence their attitudes towards deprescribing in the present.49 Rozsnyai et al. found that older adults who reported a negative deprescribing experience were less likely to support deprescribing.50 In our study, participants who reported previously taking a medication in the same therapeutic class as the medication under consideration for deprescribing in the vignette reported higher agreement with deprescribing Mrs. EF’s medication. While we did not collect information about the participants’ actual experience stopping the medication or the reason for deprescribing, it appears that it was successful in that they were no longer taking the medication. Integrating deprescribing as part of usual care and increasing older adults’ experiences with it could significantly increase deprescribing uptake throughout an individual’s life.

A key strength of our work is that it is the largest deprescribing survey to date and it included a sample of older adults across four countries with different healthcare systems. We used an experimental design which enabled the vignette to be held constant across conditions, allowing the impact on agreement with the PCP’s recommendation to deprescribe to be directly attributed to the effect of the manipulations. Furthermore, we adjusted our analysis for a range of important factors using validated scales. In addition, we worked with consumer stakeholder groups to ensure that the scenario represented a realistic and relatable person.

The primary limitation to this study is that the decisions that people make in a vignette may not align with their real-life decisions. Furthermore, we used lansoprazole to represent symptom control and simvastatin to represent a preventive medication; however, additional work is needed to see if the results would be replicated with other medications. Additional work is needed to understand the influence between specific language used in the intervention on an individual’s acceptance of a deprescribing recommendation. While our sample included substantial diversity, we make no claims that it is representative of all older adults in these countries, if only because our participants shared the common characteristic of being willing to participate in survey research using an online platform.

Conclusion

In this study using vignettes, a majority of older adults across four countries agreed with the recommendation by a PCP to deprescribe a medication for someone experiencing polypharmacy. Participants were more inclined to agree with deprescribing a medication for the treatment of a symptom rather than health prevention. Our work suggests that PCPs should focus on potential harms when discussing deprescribing recommendations. Our findings have application in future deprescribing intervention studies or to deprescribing guidelines or algorithms, as we have identified points of discussion about medications that are important to patients and may increase the likelihood of deprescribing.

References

Morin L, Johnell K, Laroche ML, Fastborn J, Wastesson JW. The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: Register-based prospective cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:289-298.

Rawles MJ, Richards M, Davis D, Kuh D. The prevalence and determinants of polypharmacy at age 69: A British birth cohort study. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(118):1-12.

Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57-65.

Sadowski CA. Deprescribing – A few steps further. Pharmacy. 2018;6:112.

2019 American Geriatrics Scoiety Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019(00):1-21.

O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, O'Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–218.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(5):827-834.

Scott IA, Le Couteur DG. Physicians need to take the lead in deprescribing. Internal Med J. 2015;45:352-355.

Pottle K, Thompson W, Davles S et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:339-351.

Ma A, Thompson W, Polemiti E, Hussain S, Magwood W, et al. Deprescribing of chronic benzodiazepine receptor agonists for insomnia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(7).

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2016;82:583-623.

Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter S, Bonner C, Irwig L, et al. Too much medicine in older people? Deprescribing through Shared Decision Making BMJ. 2016;353:i2893.

Tordoff J, Simonsen K, Thompson WM, Norris PT. “It’s just routine.” A qualitative study of medicine-taking amongst older people in New Zealand. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(2):154-161.

Bagge M, Tordoff J, Norris P, Heydon S. Older people’s attitudes towards their regular medicines. J Prim Health Care. 2013;5(3):234-242.

Linsky A, Simon SR, Bokhour B. Patient perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(2):220-5.

Todd A, Jansen J, Colvin J, McLachlan AJ. The deprescribing rainbow: A conceptual framework highlighting the importance of patient context when stopping medication in older people. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18:1-8.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;(30):793-807.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M et al. Assessment of attitudes towards deprescribing in older Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1673-1680.

Weir K, Nickel B, Naganathan V et al. Decision-making preferences and deprescribing: Perspectives of older adults and companions about their medicines. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(7):e98-e107.

Vordenberg SE, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Characteristics of older adults predict concern about stopping medications. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(6):773-780.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire, Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):510-56.

Reeve E, Low LF, Shakib S, Hilmer SN. Development and validation of the revised patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire: Versions for older adults and caregivers. Drugs Aging. 2016;33:913-928.

Weir R, Ailabouni NJ, Schneider CR, Hilmer SN, Reeve E. Consumer attitudes towards deprescribing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 2021, glab222.

Qualtrics: The experience management platform. Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com Accessed 29 October 2021.

Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Canadian Family Physician. 2017;63(5):354-364.

Thompson W et al. Continuation or deprescribing of proton pump inhibitors: a consult patient decision aid. Canadian Pharmacists Journal. 2019;152(1):18-22.

Thompson W, Hogel M, Li Y et al. Effect of a proton pump inhibitor deprescribing guideline on drug usage and costs in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016; 17:673e1–e4.

Reeve E, Andrews J, Wiese M, et al. Feasibility of a patient-centered deprescribing process to reduce inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:29–38.

Kutner, Jean S., et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691-700.

Scherer LD, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Eliciting medical maximizing-minimizing preferences with a single question: Development and validation of the MM1. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(4):545-550.

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire (BMQ): the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1998;14:1-24.

Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

Ferrer RA, Lipkus IM, Cerully J, et al. Developing a scale to assess health regulatory focus. Soc Sci Med. 2017;195:50-60.

Braithwaite D, Sutton S, Steggles N. Intention to participate in predictive genetic testing for hereditary cancer: The role of attitude towards uncertainty. Psychol Health. 2002;17(6):761-772. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044021000054764

Scherer LD, Shaffer VA, Caverly T, et al. The role of the affect heuristic and cancer anxiety in responding to negative information about medical tests. Psychol Health. 2018;33(2):292-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1316848.

Dormandy E, Hankins M, Marteau TM. Attitudes and uptake of a screening test: The moderating role of ambivalence. Psychol Health. 2006;21(4):499-511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320500380956

Ferrer RA, Klein WM, Persoskie A, Avishai-Yitshak A, Sheeran P. The tripartite model of risk perception (TRIRISK): Distinguishing deliberative, affective, and experiential components of perceived risk. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(5):653-663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9790-z.

DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:267-275.

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588-594.

Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: Screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874-877.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzche PC, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;47(8):573-577. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

Steinman MA, Fick DM. Using wisely: A reminder on the proper use of the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):644-646.

Doherty AJ, Boland P, Reed J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing in primary care: A systematic review. BJGP Open. 2020;4(3):bjpopen20X101096.

Dills H, Shah K, Messinger-Rapport B, Bradford K, Syed Q. Deprescribing medications for chronic diseases management in primary care settings: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(11):923-935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.06.021.

Greed AR, Wolff JL, Echavarria DM, et al. How clinicians discuss medications during primary care encounters among older adults with cognitive impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):237-246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05424-6

Thompson W, Jarbøl D, Nielsen JB, et al. GP preferences for discussing statin deprescribing: A discrete choice experiment. Fam Pract. 2021. 10.1093/fampra/cmab075. [Online ahead of print]

Hoffman TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: A systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274-286. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016.

Hoffman TC, Del Mar C. Clinicians’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: A systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):407-419. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8254.

Linsky A, Simon SR, Bokhour B. Patient perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(2):220-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.010.

Rozsnyai Z, Jungo KT, Reeve E, et al. What do older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy think about deprescribing? The LESS study-a primary care-based survey. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):1-11.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R24AG064025). Dr. Scherer received support via a K01 award through the National Institute on Aging (Award #: 1K01AG065440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 565 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vordenberg, S.E., Weir, K.R., Jansen, J. et al. Harm and Medication-Type Impact Agreement with Hypothetical Deprescribing Recommendations: a Vignette-Based Experiment with Older Adults Across Four Countries. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 1439–1448 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07850-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07850-5