Abstract

Introduction

To reduce inappropriate polypharmacy, deprescribing should be part of patients’ regular care. Yet deprescribing is difficult to implement, as shown in several studies. Understanding patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing at the individual and country level may reveal effective ways to involve older adults in decisions about medications and help to implement deprescribing in primary care settings. In this study we aim to investigate older adults’ perceptions and views on deprescribing in different European countries. Specific objectives are to investigate the patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed by medication type and to have herbal or dietary supplements reduced or stopped, the role of the Patient Typology (on medication perspectives), and the impact of the patient-GP relationship in these decisions.

Methods and analysis

This cross-sectional survey study has two parts: Part A and Part B. Data collection for Part A will take place in nine countries, in which per country 10 GPs will recruit 10 older patients (≥65 years old) each (n = 900). Part B will be conducted in Switzerland only, in which an additional 35 GPs will recruit five patients each and respond to a questionnaire themselves, with questions about the patients’ medications, their willingness to deprescribe those, and their patient-provider relationship. For both Part A and part B, a questionnaire will be used to assess the willingness of older patients with polypharmacy to have medications deprescribed and other relevant information. For Part B, this same questionnaire will have additional questions on the use of herbal and dietary supplements.

Discussion

The international study design will allow comparisons of patient perspectives on deprescribing from different countries. We will collect information about willingness to have medications deprescribed by medication type and regarding herbal and dietary supplements, which adds important information to the literature on patients’ preferences. In addition, GPs in Switzerland will also be surveyed, allowing us to compare GPs’ and patients’ views and preferences on stopping or reducing specific medications. Our findings will help to understand patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing, contributing to improvements in the design and implementation of deprescribing interventions that are better tailored to patients’ preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high rate of polypharmacy, commonly defined as the regular use of ≥5 medications [1], is a worldwide public health problem. Recent studies have found that the prevalence of polypharmacy in older adults is rising in the last years, ranging from 26 to 40% in Europe [2,3,4,5]. There is also evidence that patients with polypharmacy are at higher risk of inappropriate medication use [6]. Inappropriate medication use has been associated with adverse outcomes, including the increased risk for falls [7], adverse drug reactions [8], declined functional ability, cognitive capacity, and nutritional status [9, 10], poor treatment adherence [11], and impaired quality of life [12]. In Switzerland, 21% of patients with polypharmacy take at least one potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) [13]. Indeed, the prevalence of PIMs is high among older adults worldwide [14, 15]. A medication is considered inappropriate when potential harms outweigh potential benefits in an individual [16]. Adverse effects of inappropriate medication mostly affect older adults due to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes with age, increasing vulnerability and probability of drug side effects [17, 18]. The increased awareness of the harms associated with polypharmacy has led to research that focuses on deprescribing, which is defined as “the process of withdrawal (or reduction) of an inappropriate medication, supervised by a health care professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes” (definition adapted from [19]).

Deprescribing should be implemented in primary care routinely for any patient who is affected by inappropriate medication use, especially older adults [20,21,22,23]. While the evidence for deprescribing is growing, individual patients face barriers and concerns when it comes to making deprescribing decisions [24]. Previous research has shown patients’ lack of knowledge about the harms of inappropriate polypharmacy is an important barrier, while a good patient-GP relationship acts as an enabler to deprescribing [25, 26]. Additionally, some patients may fear that the offer of deprescribing is an indication that their doctor is withdrawing care or neglecting them [27]. However, the barriers and enablers faced by older adults are highly individual. As shown in Table 1, the Patient Typology was developed by Weir et al. which identified three types of older adults who vary in their attitudes towards medications, preferences for involvement in decision-making, and openness to deprescribing [28]. This can help to understand more deeply how older patients are experiencing their medications and may help to achieve patient-centred decisions about deprescribing.

In recent years there has been focus on patients’ hypothetical willingness to have their medications deprescribed. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that most of adults (84%) are willing to have a medication deprescribed [29] and similar findings have been shown in Switzerland [25, 30]. Of note, the studies conducted varied in terms of study design, population, and setting. Associations between willingness to deprescribe, clinical and participant characteristics were inconsistent across studies [29]. Furthermore, the literature mostly focuses on individual survey studies rather than systematic studies looking at deprescribing in different countries. Despite the high hypothetical willingness to have medications deprescribed, the literature shows that there is a much smaller percentage of patients, who agree with the statement: “I feel that I may be taking one or more medications that I no longer need”. Furthermore, patients also report a high level of satisfaction with their medications [29] and often indicate not being fully aware of the reasons for taking them or the potential harms caused by medications [31]. Despite the growing research on patients’ willingness to deprescribe, it remains unknown which medications patients would like to stop taking and why. Knowing this, will help designing and implementing deprescribing interventions.

Shared decision-making and patient-physician trust play an essential role in taking and implementing deprescribing decisions [32, 33]. Little is known about patients and health professionals deprescribing preferences and how these preferences compare. A recent study [33] found that patients seem to prefer continuing the use of sedatives and pain killers, but prescribers would rather discontinue these. However, this study was restricted to patients with cognitive disorders, younger than 60 years of age. In this context, it is important to better understand how GPs’ deprescribing suggestions are aligned with their patients’ preferences and how the patient–GP relationship influences deprescribing decisions. Having a better understanding of this will help to reduce disagreement in clinical practice by developing interventions that consider eventual differences [34].

While most of the literature on deprescribing focuses on prescription drugs only, for optimal medication management, GPs should be aware of all the medications used, including such supplements. Herbal and dietary supplements can be PIMs and are commonly used in many countries, including Switzerland [3, 35,36,37,38,39]. For instance, multivitamins are among the most frequently used PIMs [22, 40]. According to the Beers list and STOPPFrail criteria, Ferrous sulfate (iron), multivitamins, and caffeine are examples of PIMs and should be discontinued when prescribed for prophylaxis rather than treatment [41, 42]. Patients are commonly unaware of the potential risks of self-medication [36] and the use of such supplements is often not disclosed to GPs [39]. In this study we focus on supplements (e.g., multivitamins, vitamin D, calcium, iron, magnesium) as they are commonly used over a longer period, as compared to other medications (e.g., cold and flu medications) that can be bought over the counter in Switzerland.

Study objectives

The overall aim of this study is to investigate older adults’ perceptions and views on the use and deprescribing of prescription medications and supplements in different European countries.

Specific objectives for all participating countries are:

-

1)

To explore older patients’ views on deprescribing and compare how they differ by country.

-

2)

To assess patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed by medication type.

-

3)

To analyse if and how patients’ hypothetical deprescribing decisions are associated with the three types of the Patient Typology (a qualitative framework).

-

4)

To analyse the association between patients’ perceived trust and relationships with their GP and their willingness to make deprescribing decisions.

Additional objectives for Switzerland, where we do a patient-GP matched survey and collect additional data on herbal and dietary supplements, are:

-

1)

To compare patients’ and GPs’ hypothetical deprescribing decisions and to examine the role of patient-provider relationships with regards to the agreement between patients and GPs.

-

2)

To explore the views of patients on the use and on the reduction or stopping of herbal and dietary supplements.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This cross-sectional study contains two parts: Part A and Part B. Part A involves nine European countries (Fig. 1) with anonymous data collection on older adults’ willingness to have medications deprescribed. Part B is a nested sub-study in Switzerland only, which extends Part A by collecting additional data from older patients and GPs.

Map of participating countries created with MapChart.net. Maps created with MapChart can be freely used, edited and modified for publications, as long as mapchart.net is referenced (https://mapchart.net/terms.html, accessed July 15, 2022)

In both Part A and Part B, we are using a questionnaire to assess patients’ willingness to have their medications deprescribed, Patient Typology, and other relevant sociodemographic and clinical information on older patients with polypharmacy. For Part B, an additional questionnaire will be distributed to GPs in Switzerland, which will contain questions about the patients’ medications and the GP-patient relationship. Patients in Part B will be asked about their use of herbal and dietary supplements and their willingness to stop or reduce them. Table 2 shows further details.

Setting

The study will be conducted in primary care settings in nine European countries. It is coordinated by the central study team in Switzerland at the Institute of Primary Health Care (BIHAM) of the University of Bern and conducted in collaboration with a group of GPs from the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN) – a proven successful collaboration [43,44,45]. Seventeen National Coordinators from 13 different countries were invited to participate in the study, of which 11, coming from 8 different countries, accepted to participate (Fig. 1). Four National Coordinators are participating from different locations in Germany. The list of participant countries is subject to changes.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

For both parts, patients will be included if they are 65 years or older and have polypharmacy (taking ≥5 prescribed medications regularly). Patients are not eligible if they are unable to give informed consent or if they do not reside in one of the participating countries. For Part B, due to language reasons, the inclusion criterium for the GPs participating in the additional data collection is to be a practicing GP in the German-speaking part of Switzerland.

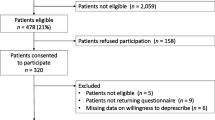

Screening and recruitment

Starting in May 2022, through the networks of the National Coordinators at each site, we aim to recruit GPs who will in turn recruit patients. For study Part A, our goal is to recruit a total of 900 primary care patients, which corresponds to approximately 100 patients per country (around 10 per GP). For Part B we will recruit an additional 35 GPs, who will invite five patients each to respond to a questionnaire and will also complete a questionnaire themselves for each of the recruited patients.

For Part A and B, primary care patients will be recruited through their GP. GPs will be recruited through the National Coordinators at the participating sites and the study team at BIHAM in Switzerland. GPs will be given screening criteria to be able to screen and recruit primary care patients in their practice. Screening criteria will be sent to all the participating GPs. Screening and recruitment of the patients will take place during the regular consultation hours of the GPs. They will be instructed to screen their patients consecutively (e.g., on a work half-day) to reduce selection bias. In the Netherlands, GPs are able to screen their patients in their electronic medical records and then invite a random sample of them.

Due to the anonymous design of Part A, patients will give their informed consent by replying to the question “by clicking yes here, I agree to participate in this study”. If they click “no”, they cannot participate in the study. For Part B, patients will have to give their written informed consent to participate. As soon as all questionnaires from one GP practice have been completed, the GP will return the questionnaire to the study team in Switzerland or to the respective National Coordinator of the participating sites.

Questionnaire

Cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire will be carried out by the National Coordinator in each participating country. Translations will be validated by performing back-translations to English and solving eventual inconsistences.

For patients (Part A and B), the questionnaire contains questions on demographic characteristics, educational level, housing and living situation, health literacy, medication management and information on life circumstances. Patients will be asked to specify any medications they would potentially discontinue, for what reason, and the support they would need to do this. Furthermore, the survey will contain questions on trust in the physician and questions on the Patient Typology. In Part B, patients will also be asked about herbal and dietary supplements. In Part B, GPs will be asked to attach the patient’s medication list to the questionnaire and indicate which medications they would be willing to deprescribe. The GP questionnaire will contain sociodemographic questions, questions about work practices, and decision-making preferences (“GP profile”) based on previous qualitative research [46]. Details on the individual components of the questionnaire, and how they related to the study objectives, are provided in Table 3.

Data collection and data management

Paper and online versions of the questionnaire will be available to participants. Part A is anonymized and thus complies with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Part B is pseudonymized and not anonymized, as we need to be able to match GPs and patients for the analysis.

We are programming the online survey using REDCap [51], which provides role-based user access control and audit trails [52]. The questionnaire will either be entered into REDCap by the National Coordinators, or the participant can fill in the survey directly online using REDCAp survey function. Only selected members of the research team will have access to the full database in REDCap.

Sample size

A recent systematic review found that 84% of patients strongly agree to have one or more of their medications deprescribed [29]. In Switzerland the results were similar with 77% of patients agreeing to deprescribe one or more of their medications [25]. For the sample size calculations, we used the more conservative estimate of 77%. The sample size calculation accounts for the clustered nature of data for patients within the same GP (ICC = 0.10), which is more conservative than the Intra-cluster correlations (ICC) of 0.01 to 0.05 that were reported for binary outcomes in cluster clinical trials of older individuals [53]. We did all sample size calculations using the power one proportion function in Stata, which allows to account for the clustered nature of the data.

Calculations for Part A

Based on the assumption that 77% of patients would be willing to deprescribe (yes/no), assuming an ICC of 0.10, we need a total of 80 clusters (i.e., GPs recruiting patients and distributing surveys, around 8 per site), and 8 patients recruited per GP, to have an effect size of 0.06 at a power of 0.90. To account for potential missing data, we increased the number of GPs per site to 10 and the number of patients per cluster to 10.

Calculations for Part B

This part of the study is powered for the GP-patient agreement related to deprescribing specific medications. In line with the literature on the agreement between GPs and patients with regards to which medication to (dis-)continue, in around half of the cases patients and GPs were in agreement regarding which medications to continue [33]. Assuming an ICC of 0.10, we need a total of 33 clusters (GPs) and 4 patients with a minimum of 5 medications each per cluster to have an effect size of 0.10 at a power of 0.90. Overall, to account for missing data, we aim to recruit 35 GPs from the German-speaking part of Switzerland, who will be instructed to recruit 5 patients each. This will result in around 175 patients and a sufficient number of medications that were rated by both GPs and patients (willing to deprescribe yes/no). There will be a minimum of 875 medications if each study participant has a minimum of 5 medications. Likely, there will be more medications to compare though, since in a previous study with a similar study population the mean number of medications was 8 [25].

Statistical analysis

Part a

From the rPATD [47], we are using the question ‘If my doctor said it was possible, I would be willing to stop one or more of my regular medications’ to assess the primary outcome for objective 1. In a sensitivity analysis, we also use the question ‘I would like to try stopping one of my medicines to see how I feel without it’ from the rPATD. The rPATD questions with 5-point Likert scale responses will be dichotomized into “strongly agree/agree” versus “unsure/disagree/strongly disagree”. If patients agree or strongly agree with this statement, they will be considered to be willing to deprescribe. Descriptive statistics will report baseline characteristics of the sample stratified by willingness to deprescribe. Where appropriate, the t-test and Chi-square test will be used to compare participants who were willing to deprescribe versus not willing to deprescribe. To explore the patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed, we will assess univariate and multivariate associations between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., age, sex, medication management, living status, education level, number of medications, etc.) and their willingness to have medications deprescribed using mixed-effects logistic regression models. Models will be adjusted for clustering effects at GP and country level. We will use a hypothesis-driven approach to select the confounders we have to adjust for. To analyse how the views on deprescribing differ among the participating sites, we will use the same regression model, but stratify by country.

For objective 2, we will descriptively analyse which types of medications patients were most likely to report as willing to stop or reduce from their own medication use. We will also compare the reasons provided for stopping or reducing by medication type. Using multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression analyses, we will also investigate patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with being willing to have certain medication types deprescribed.

For objective 3, we will assess the association between the three “types” of the Patient Typology Dimension participants identify with and patients’ hypothetical deprescribing decisions. To do so we will use a multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression model that will be adjusted for patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and clustering at the GP and country level.

For objective 4, we will analyze the associations between patient-provider relationships (reported by patients) and patients’ willingness to make deprescribing decisions using multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression analyses that will be adjusted for patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and clustering at the GP and the country level.

Part B

For objective 5, we will analyse the agreement between patients’ and GPs’ hypothetical deprescribing decisions. We will use descriptive statistics to describe the percentage of (dis) agreement between patients and GPs and which types of medications they most commonly (dis) agree about. Logistic regression models will be used to assess the association between GP-patient trust, patient and GP characteristics, and the agreement between GPs’ and patients’ willingness to make hypothetical deprescribing decisions.

Finally, for objective 6, we will investigate the use, beliefs, and motivations of patients for taking herbal and dietary supplements and their willingness to stop or reduce using such supplements. Descriptive statistics will be used to determine the percentage of patients who use supplements. Logistic regression models will be used to assess the association between patients’ demographic, behavioural, and health characteristics, the use of supplements, and patients’ willingness to deprescribe those. The analyses will be adjusted for clustering at the GP level.

Baseline characteristics will be presented in proportions (categorical variables) and means ± SD (or medians and IQR) (continuous variables). A two-sided p-value of 0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Analyses will be performed with STATA 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Discussion

Overall, the aim of our study from 9 European countries about older primary care patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed is to better understand patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing at the individual and country level. Eventually, the study’s goal is to inform effective ways to involve older adults in decisions about their pharmacological treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies comparing patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed across countries. It will also be one of the first studies to look at both the willingness to have prescription medications and supplements stopped or reduced. A better understanding of the enablers and barriers of the willingness to deprescribe in older patients with polypharmacy by answering the questions raised in this project, may contribute to improvements in the design and implementation of deprescribing interventions that are better tailored to patients’ preferences. This in turn will directly help GPs and other health professionals to optimise the process of approaching and implementing deprescribing in patients with polypharmacy. This will provide a better understanding of the management of polypharmacy and medication optimization, especially in older individuals. Ultimately this may improve patients’ overall health, reduce adverse effects caused by inappropriate polypharmacy, and eventually reduce the burden of polypharmacy on different health care systems in Europe and worldwide.

This study is strengthened by its approach to patient and public involvement, National Coordinators are partners of the Swiss central study team, and they have helped shape several aspects of the study, such as the recruitment strategy. Therefore, we aligned the data collection with all countries, to ensure feasibility of the project in regard to the format of the questionnaire, timeline of the data collection, etc. Each of the National Coordinators signed a Research Collaboration Agreement, in which the duties, tasks, qualifications for co-authorship and data use are clarified. More details on the decisions taken together with the National Coordinators are shown in Table 4. Although in Switzerland, primary care research is gaining attention, it is still a difficult context in which to conduct research. However, our team succeeded in overcoming such difficulties when conducting research involving GPs and patient recruitment in the past [43, 54]. The questionnaires (both paper-based and online version) used in this study have been piloted with 6 patients and 4 GPs and were revised based on their feedback.

Strengths and limitations

As this will be a cross-sectional study design and we will ask hypothetical deprescribing questions, the directionality of the associations cannot be confirmed. Nevertheless, our study will add important information to the literature comparing GPs’ and patients’ preferences on deprescribing specific medication types. We are limited by GDPR and the available funding and therefore cannot compare GPs’ and patients’ preferences in all participating countries but will focus on Switzerland. For Part A, due to the irreversible anonymization, we are not able to track the response rate nor are we able to adjust the analyses for the clustering effect at the GP level. However, we will be able to adjust the analyses for GP-level variables.

This study is strengthened by the fact that it will investigate which specific medications patients would prefer to deprescribe and for which reason. Another strength will be the international study design with 12 participating sites, which will allow us to compare patient perspectives on deprescribing from different European countries.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The questionnaires used in this study are available upon request.

References

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–95.

Midão L, Giardini A, Menditto E, Kardas P, Costa E. Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:213–20.

Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818–30.

Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–10.

de Godoi Rezende Costa Molino C, Chocano-Bedoya PO, Sadlon A, Theiler R, Orav JE, Vellas B, et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults from seven centres in five European countries: a cross-sectional study of DO-HEALTH. BMJ Open 2022;12(4):e051881.

Aubert CE, Streit S, Da Costa BR, Collet T-H, Cornuz J, Gaspoz J-M, et al. Polypharmacy and specific comorbidities in university primary care settings. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:35–42.

Fletcher PC, Berg K, Dalby DM, Hirdes JP. Risk factors for falling among community-based seniors. J Patient Safety. 2009:61–6.

Milton JC, Hill-Smith I, Jackson SH. Prescribing for older people. BMJ. 2008;336(7644):606–9.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(5):514–22.

Corsonello A, Pedone C, Lattanzio F, Lucchetti M, Garasto S, Di Muzio M, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications and functional decline in elderly hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1007–14.

Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(2):303–12.

Fincke BG, Miller DR, Spiro A 3rd. The interaction of patient perception of overmedication with drug compliance and side effects. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):182–5.

Blozik E, Rapold R, von Overbeck J, Reich O. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in the adult, community-dwelling population in Switzerland. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(7):561–8.

Guaraldo L, Cano FG, Damasceno GS, Rozenfeld S. Inappropriate medication use among the elderly: a systematic review of administrative databases. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):79.

Jungo KT, Streit S, Lauffenburger JC. Utilization and spending on potentially inappropriate medications by US older adults with multiple chronic conditions using multiple medications. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;93:104326.

Panel AGSBCUE, Fick DM, Semla TP, Steinman M, Beizer J, Brandt N, et al. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94.

Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(1):6–14.

Motter FR, Fritzen JS, Hilmer SN, Paniz ÉV, Paniz VMV. Potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly: a systematic review of validated explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(6):679–700.

Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(6):1254–68.

Moriarty F, Hardy C, Bennett K, Smith SM, Fahey T. Trends and interaction of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in primary care over 15 years in Ireland: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008656.

Todd A, Holmes HM. Recommendations to support deprescribing medications late in life. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):678–81.

Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, Fay M, Kearney A, Barras M. Reducing potentially inappropriate medications in palliative cancer patients: evidence to support deprescribing approaches. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1113–9.

Burge F, Lawson B, Mitchell G. How to move to a palliative approach to care for people with multimorbidity. BMJ. 2012;345:e6324.

Barnett N, Jubraj B. A themed journal issue on deprescribing. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(1):1–2.

Rozsnyai Z, Jungo KT, Reeve E, Poortvliet RKE, Rodondi N, Gussekloo J, et al. What do older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy think about deprescribing? The LESS study - a primary care-based survey. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):435.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807.

Heath I. Role of fear in overdiagnosis and overtreatment--an essay by Iona Heath. BMJ 2014;349:g6123.

Weir K, Nickel B, Naganathan V, Bonner C, McCaffery K, Carter SM, et al. Decision-making preferences and Deprescribing: perspectives of older adults and companions about their medicines. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(7):e98–e107.

Weir KR, Ailabouni NJ, Schneider CR, Hilmer SN, Reeve E. Consumer attitudes towards deprescribing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2021.

Jungo KT, Meier R, Valeri F, Schwab N, Schneider C, Reeve E, et al. Baseline characteristics and comparability of older multimorbid patients with polypharmacy and general practitioners participating in a randomized controlled primary care trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):123.

Lau DT, Briesacher BA, Mercaldo ND, Halpern L, Osterberg EC, Jarzebowski M, et al. Older patients’ perceptions of medication importance and worth. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1061–75.

Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter SM, McLachlan AJ, Nickel B, Irwig L, et al. Too much medicine in older people? BMJ. 2016;353:i2893.

Frankowski N, Grootens KP, van der Stelt CA, Noort A, van Marum RJ. 'You tell me, you are the doctor'; patients on long-term psychiatric residences about their medication. Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie. 2019;61(8):527–35.

Coran JJ, Koropeckyj-Cox T, Arnold CL. Are physicians and patients in agreement? Exploring dyadic concordance. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(5):603–11.

Marques-Vidal P, Pecoud A, Hayoz D, Paccaud F, Mooser V, Waeber G, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of vitamin or dietary supplement users in Lausanne, Switzerland: the CoLaus study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(2):273–81.

Troxler DS, Michaud PA, Graz B, Rodondi PY. Exploratory survey about dietary supplement use: a hazardous and erratic way to improve one's health? Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13807.

Werner SM. Patient safety and the widespread use of herbs and supplements. Front Pharmacol. 2014:5.

Agbabiaka TB, Spencer NH, Khanom S, Goodman C. Prevalence of drug-herb and drug-supplement interactions in older adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(675):e711–e7.

Pitkala KH, Suominen MH, Bell JS, Strandberg TE. Herbal medications and other dietary supplements. A clinical review for physicians caring for older people. Ann Med. 2016;48(8):586–602.

Paque K, Elseviers M, Vander Stichele R, Dilles T, Pardon K, Deliens L, et al. Associations of potentially inappropriate medication use with four year survival of an inception cohort of nursing home residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;80:82–7.

Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C, O'Mahony D. STOPPFrail (screening tool of older persons prescriptions in frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing. 2017;46(4):600–7.

American Geriatrics Society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–31.

Jungo KT, Mantelli S, Rozsnyai Z, Missiou A, Kitanovska BG, Weltermann B, et al. General practitioners' deprescribing decisions in older adults with polypharmacy: a case vignette study in 31 countries. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):19.

Boels AM, Koning E, Vos RC, Khunti K, Rutten GE. Individualised targets for insulin initiation in type 2 diabetes mellitus-the influence of physician and practice: a cross-sectional study in eight European countries. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e032040.

Streit S, Gussekloo J, Burman RA, Collins C, Kitanovska BG, Gintere S, et al. Burden of cardiovascular disease across 29 countries and GPs' decision to treat hypertension in oldest-old. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2018;36(1):89–98.

Weir KR, Naganathan V, Carter SM, Tam CWM, McCaffery K, Bonner C, et al. The role of older patients' goals in GP decision-making about medicines: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):13.

Reeve E, Low LF, Shakib S, Hilmer SN. Development and validation of the revised Patients' attitudes towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire: versions for older adults and caregivers. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(12):913–28.

Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:64.

Driever EM, Stiggelbout AM, Brand PLP. Shared decision making: Physicians' preferred role, usual role and their perception of its key components. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(1):77–82.

Davila H, Rosen AK, Stolzmann K, Zhang L, Linsky AM. Factors influencing providers' willingness to deprescribe medications. JACCP. 2022;5(1):15–25.

Patridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). JMLA. 2018;106(1):142.

Garcia KKS, Abrahão AA. Research development using REDCap software. Healthc Inform Res. 2021;27(4):341–9.

Smeeth L, Ng ES. Intraclass correlation coefficients for cluster randomized trials in primary care: data from the MRC trial of the assessment and Management of Older People in the community. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(4):409–21.

Jungo K, Lindemann F, Schwab N, Streit S. Hürden und Chancen der klinischen Forschung in der Hausarztmedizin. Primary and Hospital Care: Allgemeine Innere Medizin. 2019.

Declaration of Helsinki [Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

Human Research Act (HRA) [Available from: http://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/20121176/201401010000/810.305.pdf.

Ordinance on Human Research with the Exception of Clinical trials (HRO) [Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/20121177/index.html

Acknowledgements

We thank Birgitta Weltermann, Jacobijn Gussekloo, Markus Bleckwenn and Thomas Frese for their support with the conduct of this study and their editorial suggestions. Katharina Tabea Jungo is a member of the Junior Investigator Intensive Program of the US Deprescribing Research Network, which is funded by the National Institute on Aging (R24AG064025).

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Kollegium für Hausarztmedizin (KHM) through a research grant given to ZR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RL, KTJ, KW, and ZR wrote the first draft of this protocol paper. Critical review and feedback were made by RVL, KTJ, KRW, AKG, BS, DK, DMGW, FP, HT, HL, RA, RKEP, VL, ZR, SS. All authors were involved in the study design decisions and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local ethics committee in Switzerland (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern) approved the study protocol in January 2022 for Part A and B (Project-ID 2022–00035). This research project will be conducted in accordance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki [55], the principles of Good Clinical Practice, the Human Research Act (HRA) [56] and the Human Research Ordinance (HRO) [57] as well as other locally relevant regulations in the participating countries. In addition, for Part A, in order to respect privacy rights under the European regulation, the requirements of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will be fulfilled by anonymization and/or data source protection. Patients from Part A give their informed consent by replying to the question “by clicking yes here, I agree to participate in this study”. If they click “no”, they cannot participate in the study. Patients from Part B will provide written informed consent before completing the study questionnaire. All sites will also adhere to all local and national ethical guidelines for conducting research and apply for ethical approval, if necessary.

The results of this study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and the doctoral thesis of the first author. We also aim to diffuse our results in journals commonly read by GPs (for instance, the Swiss journal Primary and Hospital Care) to enable knowledge transfer.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lüthold, R.V., Jungo, K.T., Weir, K.R. et al. Understanding older patients’ willingness to have medications deprescribed in primary care: a protocol for a cross-sectional survey study in nine European countries. BMC Geriatr 22, 920 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03562-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03562-x