Abstract

In recent years, postgenomic research, and the fields of epigenetics and microbiome science in particular, have described novel ways in which social processes of racialization can become embodied and result in physiological and health-related racial difference. This new conception of biosocial race has important implications for philosophical debates on the ontology of race. We argue that postgenomic research on race exhibits two key biases in the way that racial schemas are deployed. Firstly, although the ‘new biosocial race’ has been characterized as social race entering into biological processes, it is only particular aspects of social race that are taken to cross the biosocial boundary, resulting in a distorted view of the social component of biosocial race. Secondly, racial categories are assumed to be stable across time and space. This assumption is epistemically limiting, as well as indicating a reliance on a fixed racial ontology. However, the causal pathways for the embodiment of social race, and the different possible modes of embodiment, that postgenomic science is uncovering themselves present a challenge for fixed or static racial ontologies. Given these tensions, we argue that the emerging picture of a shifting landscape of entanglement between the social and the biological requires us to increase the complexity of our ontologies of race, or even embrace a deflationary metaphysics of race.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is a long history of the problematic relationship between the biological and the social. These two facets of the human have, at various times, been conceived in opposition to each other or as inextricably intertwined (Fox Keller, 2017). In the last 20 years since the Human Genome Project, postgenomic science has stirred new interest in this long debate. Driven by rapid developments in next-generation sequencing technologies, postgenomic science characterises developmental and inheritance processes as multi-factorial systems between environmental factors, developmental mechanisms and the genome (Richardson & Stevens, 2015). As Karola Stotz (2008, p363) describes it, “[p]ostgenomic biology has brought with it a new conception of the ‘reactive genome’—rather than the active gene—which is activated and regulated by cellular processes that include signals from the internal and external environment”. Due to this close dependency between the genome and its contexts, postgenomics has been described as heralding a blurring, or even dissolution, of the biological-social boundary: it has been argued that emerging developmental and epigenetic research provides a “novel operationalization of the biological” that “no longer aims to restrain or reduce the social to it, but to create a hybrid, entangled conceptual channel in which the ‘social’ is embodied, passed on and reconstituted at each generation thus making the very texture of the ‘biological’” (Meloni, 2016, 71).

Debates over the biological-social divideFootnote 1 have extended notably to raceFootnote 2. The question of whether or to what extent racial categories or racial difference are biological has a long history. This history includes 18th Century theories of racial classification of Carl Linnaeus and Johann Blumenbach, as well as 21st Century work within population genetics that identifies genetic clusters that should correspond to human continental populations (Rosenberg et al., 2002; Spencer, 2015; see also Wills, 2017; Schiebinger, 1990). The ontology of race continues to be a subject of intense philosophical debate: competing schools of thought advocate for various senses in which race can be said to be ‘biological’, or the conception of race as a social construction, or argue that given that essentialist conceptions of race are false, race cannot refer to anything real (Spencer, 2015; Mills, 2000; Zack, 1993). In addition to these three positions on the ontology of race (termed racial population naturalism, racial constructivism, and racial skepticism by Mallon, 2007), there are several others, including ‘biosocial’ accounts proposed by Lucius Outlaw and Philip Kitcher (see Sect. 2).

Previous debates over the extent to which race is biological have focused heavily on the existence (or non-existence) of genetic differences between races (Andreasen, 2000; Sesardic, 2010; Kaplan and Winther, 2013; Spencer, 2013; Hochman, 2019). However, a new way of ‘biologizing’ race has emerged in the postgenomic age that represents an important break from previous genetic race concepts (see Duster, 2015). Developments in fields that include epigenetics, microbiome research, and the developmental origins of health and disease research paradigm (DOHaD), have found biological differences between assumed racial groups (Jasienska, 2009; Yatsunenko et al., 2012; Clemente, 2015; Galanter et al., 2017; Horvath et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2018; for discussion, see Benezra, 2020; Baedke and Nieves Delgado, 2019; Nieves Delgado and Baedke, 2021; Gravlee, 2009; Richardson, 2011; Guthman, 2014; Meloni, 2017; Saulnier and Dupras, 2017; Meloni et al., 2022).

Importantly, in this kind of postgenomic research, the discovery of systematic biological differences between races is often (although not always) taken as an effect of social processes of racialisation. In short, race is no longer defined through intrinsic characteristics of bodies (i.e., genes) but through environmentally induced and embodied as physiological and health-related difference. For example, research has suggested that differing rates of psychosocial stress and trauma (resulting from, say, racial discrimination) could lead to epigenetic changes in gene-expression patterns, which lead to racial differences in factors such as risk of cardiovascular disease and birth weight of the next generation (Kuzawa and Sweet, 2009; Aroke et al., 2019).

These kinds of investigations could provide additional justification for remedying racial health disparities, and perhaps usefully contribute to identifying targets of intervention. However, some authors have articulated worries about epigenetic research reinforcing notions of acquired inferiority of racial populations, particularly when considering intergenerational effects (Meloni, 2017), and criticised the ways in which the unreflective use of racial categories in microbiome science reinforces damaging stereotypes (Benezra, 2020).

In addition to these political considerations, there are outstanding conceptual questions about how postgenomic research characterises, investigates, and integrates the social environment and its effects on biological systems, and what this means for how social racial categories become embodied. Furthermore, these findings have important implications for philosophical debates on the ontology of race. As Hardimon (2013) notes, the concept of social race can provide a link to racial health disparities without reference to ‘innate’ biological or genetic racial differences. However, an analysis of the picture of the ‘new biosocial race’ emerging from postgenomic science appears to suggest a need to embrace more complex ontologies of race, or perhaps a deflationary picture of the metaphysics of race.

In this paper we argue that postgenomic research on race (focusing on epigenetics and microbiome science in particular) exhibits two key biases in the way that racial schemas are deployed. Firstly, although the ‘new biosocial race’ has been characterized as social race entering into biological processes, it is only particular aspects of social race or the social environment of racial groups that are taken to cross the biosocial boundary. This results in a distorted view of the social component of biosocial race. Secondly, racial categories are assumed to be stable across time and space. This assumption places epistemic limitations on how embodiment of social processes of racialization are investigated in postgenomic science. Furthermore, this assumption indicates a reliance on a fixed racial ontology. However, and in contrast to this fixity, the causal pathways for the embodiment of social race that postgenomic science is uncovering, as well as the different modes of embodiment suggested by epigenetics compared with microbiome science, themselves present a challenge for fixed or static racial ontologies. Given these tensions, we argue that the emerging picture of a shifting landscape of entanglement between the social and the biological requires us to complicate our ontologies of race, or even to face the possibility that we need to give up on the idea of a metaphysics of race altogether.

In Sect. 2 we outline the ‘new’ biosocial race concept and how it differs from older accounts of biosocial race. We then turn to two key biases in postgenomic research on race. In Sect. 3 we argue that in postgenomic research, only particular aspects of social race are taken to cross the biosocial boundary. In Sect. 4 we argue that in postgenomic research racial categories are often assumed to be stable across time and space. We then delineate the different and complex modes of embodiment entailed by research in epigenetics and microbiome science in Sect. 5. Finally, we discuss the implications this has for debates on the ontology of race in Sect. 6.

2 The ‘new’ biosocial race

The question of whether or to what extent racial categories or racial difference are biological (rather than socio-cultural) has a sordid past that bears legacies of racial essentialism, scientific racism, and its association with justifications for imperialism and slavery (Graves, 2001; Paul, 2003; Smedley and Smedley, 2005; Yudell, 2014). Nevertheless, this controversy has been reinvigorated in recent decades. This is in part due to work within population genetics which uses clustering algorithms to identify genetic human continental populations (Rosenberg et al., 2002; Ceci and Williams, 2009; Reich, 2018), and interpretations of this work as indicating a biological (genetic) basis to racial categories (Spencer, 2015; for discussion, see Ludwig, 2015).

Many researchers continue to work under the assumption that people of different races differ genetically, particularly in the context of biomedical research and investigations of differences in health outcomes (Risch et al., 2002; Bulatao & Anderson, 2004). This has not gone without extended and forceful pushback: many scholars have questioned and outright rejected race as a concept with a biological basis, on both epistemic and normative grounds (Roberts, 2011; M’charek, 2005; Tallbear, 2013). Critics have highlighted the ways in which studies that purport to show genetic differences between racial groups suffer from empirical and conceptual flaws (Lee, 2009), as well as the dangers of biological race concepts resurrecting racial essentialism and naturalising racial hierarchies (Lipphardt, 2014; Marks, 2017).

Given this history, further attempts to explore biological dimensions of race seem fraught. However, race has persisted as an analytical category in the biological and biomedical sciences. In many ways, the ‘new biosocial conception of race’ that is emerging from cutting edge developments in the life sciences is importantly different from previous genetic race concepts, as well as other notions of ‘biosocial’ race discussed by biologists and philosophers.

In genetic narratives, we have (apart from natural selection) limited ability to change the biological differences between races, and some of these biological differences act as a causal factor in generating social difference. Accounts of race as biosocial, where the biological component refers to genetic difference, tie in with this narrative. Lucius Outlaw (2014) argues for the acknowledgement that “there has been an evolutionary history producing population-distinguishing bio-cultural characteristics”, perhaps involving gene-culture co-evolution. Philip Kitcher’s (2007) account of biosocial race similarly relies upon the presumed existence of genetic clustering to provide a sense in which race is biological. This genetic clustering may, in part, have been brought about by socially-enforced norms of racial segregation, creating isolated breeding populations and therefore leading Kitcher to suggest that race is “both biologically real and socially constructed” (2007, 298).

In contrast, in postgenomic biologisation of race, the causal pathways can differ: social categories (such as racial, but also cultural and economic distinctions) have effects on biological processes other than (or in addition to) the human DNA-sequences. Racialised environments become embodied – but not genetic – biological difference; socially constructed inferiority becomes inscribed onto racialised bodies. This has changed the terms of the biological race debate: race can be biological, or have a biological component, but this need not be genetic or immutable. Furthermore, the biological component of race will more readily shift as the social construction of race shifts over time and space.

It has been suggested that racial health disparities, including the disparity in cardiovascular disease and birth weight between Black and white Americans, are in part brought about by epigenetic mechanisms (Kuzawa and Sweet, 2009). This could extend across generations: Jasienska (2009) assumes that a “multigenerational history of nutritional deprivation” (2009, 18) could explain the lower average birth weight of African Americans compared to European Americans. Epigenetics also provides a way for factors such as stress, exposure to violence or trauma, racial discrimination, or poverty to have a heritable effect on physiological processes in the body (Ohm, 2019). Racism in itself, then, could induce racial bodily difference. This research is also often combined with a ‘life course’ perspective, or falls under the DOHaD (Developmental Origins of Health and Disease) paradigm, which emphasises the role of the in utero and early life environment in producing later life health outcomes (Lumpkins & Saint Onge, 2017; Singh et al., 2019).

We find a similar trend in terms of the understanding of race in human microbiome ecology. In recent years, the microbiome has been implicated as a contributor to susceptibility to a range of diseases or conditions, including diabetes, obesity, asthma, and depression (e.g., Wang et al., 2017; Durack and Lynch, 2019; Zmora et al., 2019). Besides social factors such as lifestyle, physical activity, diet, birth, breastfeeding and hygiene practices, socio-economic status, urbanisation, and antibiotic usage practices (He et al., 2018; Porras and Brito, 2019; Quin and Gibson, 2020), human microbiome research increasingly identifies racial differences as a source of health-related microbial variation (Fettweis et al., 2014; Ross et al., 2015; Findley et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2017; for a review, see Fortenberry, 2013). Here, research tries to identify differences in the microbiome composition of different racial, or racialised, groups (including Black or white groups, western or Indigenous groups, US American or Hispanic groups). Although sometimes narratives about the host’s genetic background are invoked to explain (part of) such microbial differences, typically assumed sociocultural variation across races plays a key explanatory role.

The shift away from genetic and potentially essentializing conceptions of race, alongside a deepening understanding of the biological effects of social racial hierarchies, has been welcomed by some scholars. Gravlee (2009) suggests that an understanding of the biological effects of race and racism could offer a “constructive framework for explaining biological differences between racially defined groups”. Similarly, Kalewold (2020) suggests that understanding the mechanisms by which social racial difference can become embodied can help us explain racial health disparities without reifying the genetic race concept. This new conception of biosocial race could allow for the recognition and even integration of social constructionist perspectives on race, together with a nuanced understanding of the impacts of social processes of racialization that sits alongside a biologically informed approach. It has been argued that this new conceptualisation could have not only epistemic but also political and pragmatic effects: Sullivan (2013) suggests that “by illuminating the transgenerational scope of white racism, epigenetics can be a useful ally in that fight”. According to Roberts (2016, 121), the biosocial paradigm has the “potential to advance justice because it starts from the premise that social inequality is not natural”Footnote 3. Whilst genetic theories of race have led to political projects that posit racial inequality as natural and thereby unchangeable (and sometimes even desirable), seeing race as biosocial could provide further impetus to change unjust social conditions (given that they have not only social but also physiological and intergenerational effects).

On the other hand, several scholars have been more skeptical of the new biosocial race concept, both with respect to epigenetics and microbiome research, often raising concerns regarding its broader social or political implications (see Meloni, 2017; Saulnier and Dupras, 2017; Saldaña-Tejeda, 2018; Saldaña-Tejeda and Wade, 2018; Benezra, 2020; Baedke and Nieves Delgado, 2019; Meloni et al., 2022; Nieves Delgado and Baedke, 2021). For example, Mansfield (2012) points to the concept of embodied race as attaching responsibility to individuals as producers of biological, and thereby racial, difference, and Mansfield and Guthman (2015, 12) argue that “epigenetics produces an intensified racialization because it redefines difference as epigenetic damage”.

It seems, therefore, that the ethical and political implications of the new biosocial race concept remain contested. In addition, there are outstanding questions regarding how the social and biological are related to one another in postgenomic science. This has crucial implications for philosophical debates on the ontology of race. In Sects. 3 and 4 we argue that there are two key biases operating in postgenomic investigations of race, which lead to a distorted picture of racial categories as biosocial,.In Sect. 5 we delineate differing modes of embodiment in epigenetics as compared with microbiome science, and its implications for our understanding of the ontology of biosocial race.

3 The ‘social’ in biosocial race

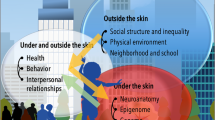

In these new biosocial accounts of race, the aspects or features of the social environment that become embodied (and therefore have biological effects which are measured in postgenomic science) display systematic biases.Footnote 4 We suggest that this results in a conception of biosocial race where it is not ‘social race’ in full that is understood as becoming embodied, but rather only particular aspects taken to be representative of racial environments. We highlight the ways in which postgenomic research into the ‘embodied social’ overwhelmingly focuses on firstly, the ‘negative’ social environment that contributes to harmful health outcomes, and secondly, the effects of this negative environment on members of ‘racialised groups’, and explore the implications this restricted focus has for understanding ontologies of race. Although the problematic distortions emerging in postgenomic science have been studied in detail (examples include Benezra, 2020; Mansfield, 2012; Meloni et al., 2022), the consequences of these distortions for constructing racial ontologies has been neglected.

As this research is often framed relative to the goal of addressing health disparities, the focus on the negative effects of particular social environments on minoritised racial groups appears warranted. Whilst the selective permeability of the biological-social boundary does not per se result in troubling epistemic or political implications, the narrow focus on selective aspects of the social environment can have unintended consequences. Furthermore, importantly, this poses a challenge for our understanding of the underlying ontologies of race.

We see this restricted characterisation of the social across postgenomic science. Epigenetic research has focused on the impact of factors such as air pollution, psychosocial stress, and rates of smoking which differ between racial groups. These factors could then lead to differentially methylated genomes, and therefore contribute to racial disparities (often between African Americans and European Americans) in the incidence of health outcomes that include rates of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, preterm birth, metabolic syndrome and chronic pain (Vick and Burris, 2017; Burris et al., 2020; Salihu et al., 2016; Song et al., 2015; Saban et al., 2014; Aroke et al., 2019; Chitrala et al., 2020).

Similar trends arise in scientific investigations of the human microbiome. Research into vaginal microbiome composition has found differences between racial groups (again, typically between African Americans and European Americans), with these differences thought to contribute to differential rates of bacterial vaginosis and preterm birth (Ravel et al., 2011; Fettweis et al., 2014; Hyman et al., 2014; Serrano et al., 2019; MacIntyre et al., 2015). Whilst genetic differences are sometimes invoked as a possible partial explanation for these findings, researchers also point to the role of environmental influences. Findley et al. (2016), in their proposal for investigating health disparities in the microbiome, argue for combining studying microbiome composition with detailed characterisations of the social environment, that include chemical exposures and social factors such as poverty, violence, stress, limited access to healthy food and healthcare.Footnote 5

In both epigenetic and microbiome studies, when the features of the environment that could drive disparities are considered, it is the environment of racial minorities (such as Black Americans) which is the focus, and the negative features of this environment in particular (the ones that could contribute to poorer health outcomes). For example, in a 2019 study by Aroke and colleagues that investigated epigenetic differences as an explanation for racial disparities in chronic pain, the authors provide a contrast between two hypothetical individuals: one is an African American who experiences “low SES [socioeconomic status], abuse and neglect” and “gang violence, racism and bullying”, which leads to epigenetic changes resulting in chronic pain later in life. They contrast this with a white man who experiences a “nurturing environment, balanced diet” and comparatively mild stress of “school, role identity and confusion, balancing first job”. This results in some mild epigenetic changes for stress adaptation and therefore “healthy ageing” and only mild chronic pain. In these studies, the environment of white Americans or Europeans often implicitly provides a ‘neutral’ contrast class against which impoverished environments are compared. However, the valence of the chosen contrast class is not, in actuality, ‘neutral’, but rather involves a conception of these populations as representing a ‘default’ implicit healthy state.

Racial health disparities are urgent problems that need to be addressed. Understanding the ways in which socially constructed racial hierarchies can drive biological difference could potentially provide fruitful avenues for addressing these disparities. However, it is important to be aware of the conceptual picture of the relationship between the social and the biological that emerges, and the implications this has for the integration of biological and social ontologies of race, which have so far been under-explored.

To understand this let us look at social constructionist accounts of race. Some scholars have proposed accounts where what races are (or how they should be understood) is, centrally, in terms of a racial hierarchy, where some groups are privileged and others subordinated (some examples include Mill,s 2000; Haslanger, 2000; Ludwig, 2019, although there are important differences between the aims and details of these accounts). Others have explored how racial identity forms and what it comes to mean to individuals (Haslanger, 2005).

Michael Hardimon (2013), in his account of the use of race concepts in medicine, argues for the use of “socialrace” in medical contexts. He defines socialrace as “a social group that is taken to be a racialist race” (p. 14). By this he means that, ontologically, socialraces are kinds of social positions (such as in Haslanger’s 2000 account, where races are or ought to be understood in terms of positions on a hierarchy). Without the social practices that maintain these patterns of social relations, socialraces would not exist. In addition, socialraces for Hardimon are social groups which are taken to be specific kinds of biological groups, “racialist races”; that is, essentialist and hierarchical divisions of the human species based on physical difference. This allows us to understand how socialraces can be used within a racist society to justify racial subordination without any commitment to the reality of a racialist or essentialist biological race concept. Hardimon suggests that “socialrace is a biologically salient social category” (p. 16). He draws on Nancy Krieger’s notion of embodiment, as the “biological incorporation of the social experience of inequality into the human body” (ibid.) to argue for the utility of socialrace as a tool for understanding the social aspect of the biosocial embodiment process. A similar process could be said to be occurring in postgenomic investigations of race: without assuming any essential or genetic racial difference, socialrace affects the social environment of individuals, and this has effects on gene expression patterns or features of the microbiome.

Whilst socialrace functions, as Hardimon suggests, as a useful discursive tool to avoid confusion with biological concepts of race in certain medical contexts, there is a potential danger when considering the ontological question of race as biosocial. We can see this danger clearly when we consider one social constructionist account of race. Jeffers (2013) argues for a cultural concept of race which can be conceptually separated from the ‘political theory of race’ as racial hierarchy. Although the formation and maintenance of racial categories relies on historical and current hierarchies of privilege and disadvantage, this has resulted in socialising individuals into particular ways of life, and these ways of life have value. Jeffers stresses the positive aspects of this cultural concept (ibid, 422; emphasis added):

What it means to be a black person, for many of us, including myself, can never be exhausted through reference to problems of stigmatization, discrimination, marginalization, and disadvantage, as real and as large-looming as these factors are in the racial landscape as we know it. There is also joy in blackness, a joy shaped by culturally distinctive situations, expressions, and interactions, by stylizations of the distinctive features of the black body, by forms of linguistic and extralinguistic communication, by artistic traditions, by religious and secular rituals, and by any number of other modes of cultural existence.

The general point here is that there are many facets to a social analysis of race, which will incorporate and grapple with not only inequality and disadvantage, but also joy, community, solidarity, and so on. In contrast, the social environment that becomes ‘embodied’ is primarily understood through its negative biological effects. In older accounts of biosocial race which rely on genetic difference, race is both biologically real, in that it corresponds to real genetic population divisions, and socially constructed, in that the social groupings themselves (and associated social practices such as enforced segregation) lead to genetic difference. In the ‘new’ biosocial race, the postgenomic research which investigates embodiment gives us only a partial and limited snapshot of how some aspects of the social environment might affect biological processes in racialised groups.

The postgenomic view of racial environments not only stereotypes social environments in terms of their health-diminishing aspects; these environments become further pathologised through an exclusive focus on the environments of racial minorities. Yearby (2020), in her critique of the use of both genetic race concepts and thinly conceived social race concepts in medicine, points to the way that white people become the ‘control group’ or the standard, and argues that this reinforces racial hierarchies. While Yearby is critiquing the use of race in medicine broadly (including in, for example., clinical drug trials), this also applies to studies in postgenomic biomedicine (such as those described above), where the environment of white individuals is positioned a standard against which ‘worse’ environments are compared. This also has implications for ontologies of race as biosocial. In many social constructionist accounts, all races are defined in terms of their position on a social hierarchy. This has implications for treatment of these groups and their social environment in many domains. However, in postgenomic research in this area whiteness becomes ‘de-raced’, and acts as a neutral standard of comparison. This has epistemic limitations, in that there are lacunae in understanding of the ways in which racial stratification might have effects on all racial groups. Furthermore, this points to another way in which the ‘new’ biosocial race does not simply involve the reaching of ‘social race’ into the body. This is because in social ontologies of race, white individuals are not a neutral standard, but are also a socially constructed race (for example, occupying a particular position on the racial hierarchy). Thus, any possible ontology of race must take into consideration that biological race is affected by a highly complicated, selective, and normatively-biased snippet of the embodied racial environment.

4 Stability across time and space

The second key bias in postgenomic science that has implications for the ontology of race is the assumption of stability across both time and space. We demonstrate how these assumptions arise in postgenomic research on race and suggest that this leads to both epistemic limitations in this work and requires more complex ontologies. In particular, ontologies of race appear to become decoupled from spatio-temporal changes, and race is mapped onto entities in non-spatio-temporal ways; this may make research on race in postgenomics more tractable but leads to important limitations.

Let us first consider the idea that social life of certain ethnic or racial groups does not change over time. The assumption that some groups, often non-Western and indigenous, represent pristine societies of the past is often present in postgenomic science. However, this idea is not exclusive to postgenomics. Instead, it emerges from a long history of (neo-)romantic anthropological research since the 18th century (Kressing, 2012) and population genetic approaches to race since the 20th century (Wade, 2017). In the latter, a central first aim to study racial difference was to identify a research population that shows genetic homogeneity, if possible, over an evolutionary relevant time scale. One way to preserve such homogeneity was via geographical isolation, a theoretical prerequisite since pre-WWII race science and its attempt to identify ‘Mendelian pure lines’ in humans (see Lipphardt, 2012). Besides such ‘geographical isolates’, a high genetic stability was considered to be secured through certain lifestyles or cultural practices (language, marriage rules, religion, etc.) that make gene flow between group and non-group members impossible or highly improbable. These assumptions about ‘social isolates’ made populations like Ashkenazi Jews or American Amish central research targets (see Azoulay, 2003; Francomano, 2012).Footnote 6

In this history of human population genetics ‘social isolation’ was often linked to ideas of purity and fixity (in contrast to mixture) of a certain race (Suárez-Díaz, 2014; Wade, 2017). Echoes of these assumptions still haunt genetic sampling methods today, even in projects mapping global genetic diversity such as the Human Genome Diversity Project (Bliss, 2009; Reardon, 2008; TallBear, 2007; Kressing, 2012). These assumptions about isolatedness of certain populations – what Pálsson (2007) calls the ‘island model’ – usually are used to hypothesize about the past evolutionary history of a group. In this context, socially (and geographically) isolated populations, especially indigenous groups, are considered to offer a glimpse into an evolutionary ‘aboriginal’ past of humankind, an ancient and pristine state that is reflected in certain gene frequencies. For this island model to work, not only selection pressures but the social environment of these groups needs to be ‘frozen in time’ (see Marks 1995; Leavitt et al., 2015). The social has to be static. While ‘more advanced’, socially stratified and demographically dominant Western cultures and societies should have displayed rapid social dynamics in the last centuries, these indigenous populations – their genes, indigenous knowledge, and culture – are assumed to have remained unchanged (see Kressing, 2012).

Even though postgenomics promises to provide a new and fresh look at the relationship between the biological and the social, the older primordialist assumptions about the social stability and purity of indigenous populations is still very much alive. In these new racial studies, too often, social stability creates not (only) genetic homogeneity, but epigenetic or microbial homogeneity. In microbiome research, narratives about isolation and uncontactedness of indigenous groups are often introduced to legitimize assumptions about the stability of primitive, non-western lifestyles, and thus of socially-induced stable microbial patterns in these groups (Maroney, 2017; Benezra, 2020).Footnote 7

For example, since the 1950s and not least due to James Neel’s work on the ‘thrifty genotype’, the Yanomami in Venezuela were a target of extensive anthropological and human genetic studies. For Neel the “world of primitive man is remarkably uncontaminated” (1970, 820). This view has not much changed in the microbial age. In their study of the microbiome diversity and composition of Yanomami, Clemente et al. (2015, 1) describe this group as “an uncontacted community [that] therefore represent[s] a unique proxy for the preantibiotic era human resistome”. Thus, while the Yanomami have changed from being an exemplar of metabolic disorders and obesity (as in Neel’s work) towards an exemplar of primordial health (due to their diverse microbiome), the basic simplistic assumptions about the group’s social isolation and stability remain unchanged. Still, this and other indigenous groups should allow westerners a glimpse into their ‘aboriginal’ past, into an ancient and pristine state that provides knowledge for biomedical applications. Besides the Yanomami, central ethnic groups currently under investigation are, among others, the Hadza in Tanzania with their “very ancient traditional lifestyle” (Schnorr et al., 2014) or the Matses in Peru with their “ancient bacteria” (Gibbons, 2015). In epigenetics, similar views about the stasis and primitivity of the social (including its biomarkers) are increasingly surfacing to legitimize the selection of indigenous research communities (for discussion, see Saldaña-Tejeda and Wade, 2018).

This primordialist framework to understand indigenous cultures and bodies, inherited from the history of anthropology and human population genetics, is continuously used in postgenomics to legitimize scientific and medical purposes (similar to, for example, the Human Genome Diversity Project). As a consequence of this trend, the narrow identity prototypes developed in this framework – about indigenous’ pristine ‘postgenomic condition’ that allows a glimpse into westerners’ ‘aboriginal’ cultural past – have started to affect medical doctors (Saldaña-Tejeda and Wade, 2018) and public media (Anderson, 2015). For example, in a public article of the American Society for Microbiology on microbiome sampling, the author summarizes: “bacterial cultures also represent human cultures. These microorganisms are a tangible byproduct, a living legacy, of distinct ways of life and shared evolutionary histories” (Corzett, 2019).Footnote 8

These simplistic, quasi-essentialist assumptions about indigenous stable cultures and bodies in race-based postgenomic research, become even more surprising given the highly dynamic picture of the epigenome and microbiome other studies in these fields point towards: Here, gene expression patterns and microbial compositions are not culturally stabilised and frozen in time, but highly fluid or transient over seasons and across life cycles, as they mirror the cultural complexity and transitions between various life styles, nutritional habits, and changes in the social and material environment. For example, in the Hadza in Tanzania we see fluctuations in the nutritional habits depending on seasonal and annual changes in food resources (Rampelli et al., 2015). In fact, these fluctuations are so large that during some time of the year (in the dry season when Hadza people eat a lot of meat) the composition of microbiota is surprisingly similar to that of ‘Western industrialised societies’ (Smits et al., 2017).Footnote 9 What is more, against the view of social isolation, one needs to highlight that, for example, microbes travel much faster than human contact (e.g., through trade and soil exposure) and many of the indigenous populations chosen, despite their apparent isolation, had direct contacts with anthropologists and human geneticists. These findings make characterizations of the temporal stasis and purity of the social environment of racial and ethnic research populations questionable, including their simplistic juxtaposition with ‘western civilizations.’ Here we see the ways in which our understanding of epigenetic processes and microbiome dynamics give us reason to increase the complexity of our racial ontologies. This is in stark contrast to the predominant assumption of fixed and stable ontologies that appears to shape or guide research in these areas. Here we see a conflict between an underlying ontology that assumes stability in microbiome research, against empirical findings of temporal fluctuations in microbial patterns.

Besides such biased views of the fixity and stasis of the social over evolutionary time, other biosocial studies in postgenomics assume racially specific cultural features to be stable across space, especially across national borders. Conceptually, race as understood biosocially should be able to accommodate shifting boundaries and meaningfulness of racial categories across space. The ways in which social racial hierarchies produce racial difference differ depending on geographic and national context, and therefore we would expect the ways in which social race becomes ‘embodied’ in biological processes to vary also. However, in practice, research around biosocial race often reveals the assumption that biosocial race is spatially stable, and therefore that findings from one particular geographic or national context can be easily exported to other contexts. The assumption of stability across space has been under-explored in the literature, in the context of microbiome research in particular, thus far. This has important implications for ontologies of race: races become decoupled from space and place, and this underlying ontology of a non-spatially varying race leads to dangerous biases in how race is studied. We highlight two potential dangers: firstly, findings from one national context may be assumed to apply in different contexts with different racial dynamics. Secondly, assuming that biosocial races are spatially stable could prevent exploring whether these findings could apply to other, non-racial, social hierarchies.

The expectation that findings of biosocial racial difference in one country or setting can be easily applied to different settings is misguided: if it is social processes of racialisation that drive biological differences in the epigenome or microbiome, and if social processes change over space, we would expect these biological differences to also shift. As a recent analysis of the use of race in human microbiome research emphasises (Nieves Delgado and Baedke, 2021), in many national contexts racial politics work very differently than in the US, where many microbiome studies are carried out. This study points to the case of racial categories in Latin America, where racial self-ascription is less common and is not regularly recorded for administrative purposes. One illustration of the risk of this assumption of stability comes from vaginal microbiome research. For example, Ravel et al., (2011) characterised the vaginal microbiome of 396 US American women, sorted into the ‘ethnic groups’ of white, Black, Asian and Hispanic. The study authors found that Black and Hispanic women exhibited differences in vaginal microbial community composition in comparison to white or Asian women. These findings could possibly indicate a connection between particular racialised social environments and how they impact the microbiome (although, this research still suffers from the biases outlined above). However, the implications of this work have not been restricted to the US; rather, this research has spurred investigations in other contexts. Mehta et al., (2020) cite the Ravel et al. study, amongst others, as a motivation for characterising the Indian vaginal microbiome. The implication here is that the investigation of the vaginal microbiome composition of Indian women could add to our understanding of racial or ethnic diversity in the vaginal microbiome in general. However, this assumes a stable conception of race globally. Data collected from Indian women living within India cannot reliably be inferred to apply to or represent women of Indian descent living in other places, such as the United States. A Hindu ‘Indo-Aryan’ woman in India could be understood as belonging to a dominant racial group (although the way that race operates in India is contested, see Rai, 2021) and will likely not experience racial discrimination or subordination based on race. However, this may not be true for the same woman in an US American setting.

Furthermore, this assumption of stability could also hinder the productive exploration and application of biosocial research to non-racial social hierarchies. If the biological aspect of biosocial races is taken to come about through racial hierarchies, which result in racial minorities experiencing disproportionate psychosocial stress, discrimination, and poverty, amongst other factors, then presumably these findings would have some relevance for non-racial hierarchies that result in similar inequities. One potential example is the caste system in India. Despite government-imposed affirmative action programmes, caste disparities in economic and health outcomes still persist (Deshpande, 2000; Dutta et al., 2020). It appears plausible that this ongoing social marginalisation could contribute to epigenetic or microbiome difference. However, postgenomic research along these lines has been limited, and there has been no attempt to utilise findings around biosocial race to understand the effects of this system.

This bias towards assuming stability across space is therefore epistemically limiting. In addition, the dynamic nature of the epigenome and microbiome give us reason to move away from stable ontologies, and require us to complicate our ontologies across both space and time.

5 Differing modes of racial embodiment

We have argued that there are two biases in postgenomic research on race: firstly, a focus on the negative social environment of non-white groups, and secondly, an assumption of stability across time and space. We have suggested that these biases introduce epistemic limitations, whilst also carrying implications for a biosocial ontology of race. Despite assumptions of fixity or stability, the range of causal pathways and modes of embodiment suggested by postgenomic developments appear to necessitate expanding or complicating our ontologies of race.

Both affirmative and critical perspectives on how postgenomics affects our understanding of race often neglect that there is a range of different pathways through which the social environment could be embodied as racial patterns. In fact, epigenetics and microbiome research draw on quite different ontologies to understand how race is embodied. In the case of epigenetics, environmental cues can change an individual’s gene expression patterns, which can have intra- or trans-generational effects. In the case of the microbiome, embodiment is represented by the presence or relative proportions of different microbial species (the function or composition of a particular microbial community, e.g., in our guts) which are affected by the environment. The processes and products of the embodied microbial community have a variety of biological or physiological effects on the biology of the host individual, which microbiome scientists are aiming to uncover and catalogue.

Across these two fields alone we see a wide difference in the (i) mode of embodiment and (ii) causal factors producing racial traits. This means that, for example, dietary differences due to social deprivation that lead to type II diabetes in certain groups are studied as racial health patterns in quite different ways. While the channel – diet – is the same in both fields, in epigenetics, what is embodied is certain nutritional components (e.g., vitamin B12 or betaine) that affect biochemical pathways and ultimately DNA-methylation patterns causing ‘racial’ health patterns; in contrast, in microbiome research, what is embodied is other organisms (microbes), which form the microbiome that brings about ‘racial’ health patterns, like type II diabetes, in certain hosts.

The latter microbial view of embodiment shows even more nuances, depending on how the microbiome-host relationship is conceptualized. Sometimes the microbiome is interpreted as the collection of all genomes of these microorganisms. Then the host and microbiome together for a hologenome (Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2019). In this case, embodiment through diet means extending the genome of hosts that then show ‘racial’ traits (produced through microbial DNA). This ‘postgenomic’ view of race is quite gene-centered: it is non-human DNA-sequences that then work as markers to cluster human groups into races. Another view of embodiment in the field, focusing on taxonomic patterns (diversity and abundance) of microbial species, constructs racial traits of certain hosts as resulting from organism-organism interactions between microbes and humans. Here we eat other species these then work as markers to distinguish different races of host groups. This view is taxonomically problematic, as it ultimately holds that human races are constituted by other non-human species. In addition, it decouples a biologically informed concept of race from the traditional idea of ancestry (i.e. racial patterns are inherited), since microbes and their human hosts do not form a common linage (for discussion, see Nieves Delgado & Baedke, 2021).

We come to see that postgenomic research does not point towards one consistent and coherent view of how social environments bring about racial patterns in certain groups. Instead, what emerges is a diversity of ontological frameworks. Both the embodiment and causal production of racial traits builds on a range of quite different ontologies – from non-genetic and somatic embodiment and production of race (in epigenetics) to extended genomes and gene-essentialism or symbiotic relationships that underlie racial patterns (in microbiome research).

6 Conclusion and outlook

A new concept of biosocial race appears to be emerging from research on embodiment, including within postgenomic research, and fields such as epigenetics and microbiome science in particular. The new biosocial race does not involve genetic difference, as with previous accounts of biosocial race. Rather, it is socially constructed race that has non-genetic biological effects, such as changes to gene expression patterns and changes in microbiome composition or function. Social race appears to become ‘embodied’. We have argued that in postgenomic research on race, we see two key biases in the way that racial categories are used, with implications for the underlying racial ontologies.

Firstly, although the new biosocial race has been characterized as social race entering into, having effects upon, or becoming entangled with biological processes, it is only certain aspects of social race (or the social environment of racialized groups) that are characterized in this way. In particular, it is often primarily the negative or harmful features of the social environment of non-white groups which are measured and investigated in terms of how they become embodied. In addition to the potential for pathologizing non-white groups or particular racialiaed environments, this has implications for how we understand the new biosocial race concept. Importantly, it is not the case that ‘social race’ as a concept is what enters into biological processes and becomes embodied. This is because ‘social race’ encompasses much more than the negative features of non-white social environments. Accounts of race as socially constructed sometimes involve complex positive aspects of identity and culture, and see all groups on the racial hierarchy as ‘raced’, rather than white individuals acting as a control or neutral standard. Both these aspects of social race are potentially important for understanding the interplay between the social and the biological, as well as how this impacts health.

Secondly, in postgenomic science racial categories or racial ontologies are often assumed to be stable across both time and space. These assumptions result in important epistemic limitations, and indicate a reliance on a fixed and stable racial ontology. The assumption of stability over time, as can be seen in microbiome studies on Indigenous groups, mischaracterizes these cultures and misses crucial dynamics of fluctuation and change. The assumption of stability across space, as can be seen in attempts to characterize the vaginal microbiome of different groups, leads to inappropriate importing of findings from one social context to another. In addition, this assumption prevents the productive exploration of connections between findings of the impact of racial difference on the microbiome and those same impacts in cases of other non-racial forms of social marginalization.

In contrast to these assumptions of a singular or fixed racial ontology, the causal pathways and modes of embodiment investigated in postgenomic research themselves present a challenge for fixed or static racial ontologies. This is because findings from epigenetics and microbiome science point not to one single and unified, but rather complex and shifting landscape of the interaction between the social and the biological, depending both on the social context and the pathways through which this interaction occurs.

How should we make sense of our ontologies of race in light of this biosocial complexity? Ludwig (2019) develops a framework for addressing racial ontologies on a global scale. He argues that current metaphysical debates on race are usually centered around the United States, and the arguments made are restricted to the US context. This is typically justified through the assumption that ‘race does not travel’. However, this ignores transnational continuities between racial ontologies, and potentially obscures the global nature of processes of racialization. On the other hand, attempts to identify a ‘world concept’ of race run the risk of ignoring transnational heterogeneity. Ludwig suggests a shift to a framework that focuses on various ‘conceptions’ (rather than concepts) of race, which analyses three dimensions: heterogenous conceptual connections, material property relations, and mappings between them. This move away from either assuming a single conceptual core of race across different contexts, or assuming different conceptual cores of race, allows for a fine-grained comparison of the existence and strength of transnational continuities and discontinuities. Under this framework, race conceptions do not provide clear answers to what the referent of race is, but rather this way of understanding race complements a deflationary perspective on the metaphysics of race. As Ludwig (2015, 258) argues, race “is too ambiguous and vague to support a general metaphysical debate about the question whether human races exist”.

The dynamicity of the postgenomic processes through which the biological and the social become entangled further complicates projects that aim to identify a conceptual core of race and assume a fixed or stable ontology (even within a given national setting). The extent to which, or the ways in which, race can be said to be biosocial will vary significantly depending on the context. Perhaps in some contexts social processes of racialization have strong effects on either gene expression patterns or microbiome composition (or both), and this means that race must be understood biosocially. Perhaps in other contexts these effects are less pronounced. This may change over time or space. Ludwig’s framework of conceptions of race would allow for the identification of those contexts where race is biosocial, the specification of the ways in which race can be said to be biosocial, the drawing of connections between race as biosocial and other aspects of a particular conception of race, and comparison between a given biosocial conception and others.

Although this does not require adherence to a deflationary metaphysics of race, it makes such a metaphysics more attractive or plausible. There appear to be two possible responses to the postgenomic complexity that we have highlighted: we could increase the complexity of our racial ontologies in order to attempt to accommodate all possible differences, or we could reject the ideal of a fundamental ontology of race and acknowledge that our racial classifications deeply depend on how ‘race’ is specified.

Developments in postgenomic science indicate that there are multiple causal pathways and modes by which social race might become embodied. These findings in epigenetics and microbiome science appear to provide support for a new concept of biosocial race, where the ways in which the social and the biological become intertwined are dynamic and shifting. However, there is a clear tension between the complex causal pathways of racial embodiment proposed and explored, and the assumption of fixed racial ontologies that appear to underlie many studies in these fields. Thus, in face of postgenomic research, today’s race studies face the challenge to conciliate these two views. As a solution to this problem, we suggest that the emerging picture of a shifting landscape of entanglement between the social and the biological requires us to significantly increase the complexity of our ontologies of race, or even embrace a deflationary metaphysics of race.

Notes

These debates often rely on the problematic assumption that the ‘biological’ and the ‘social’ are discrete, unified, unitary categories that can be juxtaposed against each other. On different historical attempts of drawing this boundary, e.g., in the works of Durkheim, Weismann, and Kroeber, or on blurring it, e.g., in the work of Spencer, see Kronfeldner (2009), Keller (2017), Lock & Palsson (2016), Meloni (2016, 2017), and Meloni et al. (2016).

The relationship between race and ethnicity is complex and debated amongst philosophers. Gracia (2017) adopts a “genetic common bundle” view of race, whereby race is understood in terms of common descent and genetic features which result in phenotypes commonly associated with a racial group (the choice of which is socially constructed), and a “historical familial” view of ethnicity, where ethnicity is conceived in terms of family and history, relying on contingent historical events. Generally, ethnicity often is taken to involve a cultural component that is not taken as necessary for race, although the boundaries between them can be blurred and ethnicities can be ‘racialised’ (Blum, 2009). Here we discuss race and racialised groups; similar questions may also arise for groups that are typically considered ethnicities, or ‘ethnoraces’ (such as Latinos, see Alcoff, 2009).

It is important to note that Roberts simultaneously urges caution here, noting that although new biosocial science carries this potential, it “can be stymied when some scientists import old biosocial assumptions and frameworks into the new biosocial science” (2016, 121-2).

We recognise that the concept of ‘social environment’ is slippery and somewhat opaque. However, here we refer to the sets of variables or proxies that postgenomic scientists use in their research to measure features of the ‘social environment’, that include, for example, poverty and psychosocial stress.

Note that we also find the stereotyping of non-Western groups as ultimately healthy due to their primitivity, naturalness, or traditional purity (see Maroney, 2017; Benezra, 2020), particularly in studies on the microbiome of Indigenous groups that live as hunter-gatherers or rural agriculturalists. Whilst this is a focus on ‘positive’ aspects of the social environment, rather than negative, similar worries might arise: only particular (positive, or health promoting) features of the social environment are taken to become embodied.

Assumptions of primitivity and ‘primordial’ environments are not limited to population genetics: For example, Wald (2008) highlights the ways in which these assumptions became part of the narrative of the African or Haitian origins of HIV.

For a reflected counterexample, see Yong (2015, emphasis in original): “The Hadza and the Matses are not ancient people, and their microbes are not “ancient bacteria” […]. They are modern people, carrying modern microbes, living in today’s world, and practicing traditional lifestyles. It would be misleading to romanticise them and to automatically assume that their microbiomes are healthier ones.”

Interestingly, not only indigenous cultures but also those of Westerners seem to show seasonal fluctuations in diet (see van der Toorn et al., 2020).

References

Alcoff, L. M. (2009). Latinos beyond the binary. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 47(Supplement), 112–128.

Anderson, A. (2015). Study Reveals Microbiome Diversity, Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Isolated Amazon Tribe, Genomeweb. Available at: https://www.genomeweb.com/sequencing-technology/study-reveals-microbiome-diversity-antibiotic-resistance-genes-isolated-amazon (Accessed: 27 November 2021).

Andreasen, R. O. (2000). Race: Biological reality or social construct? Philosophy of Science, 67, S653–S666.

Aroke, E. N., Joseph, P. V., Roy, A., Overstreet, D. S., Tollefsbol, T. O., Vance, D. E., & Goodin, B. R. (2019). Could epigenetics help explain racial disparities in chronic pain? Journal of pain research, 12, 701.

Azoulay, K. G. (2003). Not an innocent pursuit: the politics of a ‘Jewish’ genetic signature. Developing World Bioethics, 3(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-8731.2003.00067.x

Baedke, J., & Nieves Delgado, A. (2019). Race and nutrition in the new world: colonial shadows in the age of epigenetics. Stud Hist Philos Sci C, 76, 101175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2019.03.004

Benezra, A. (2020). Race in the Microbiome. Science Technology & Human Values, 45, 877–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243920911998

Bliss, C. (2009). Genome sampling and the Biopolitics of Race. In S. Binkley, & J. Capetillo (Eds.), A Foucault for the 21st Century: Governmentality, Biopolitics and Discipline in the New Millennium (pp. 322–339). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Blum, L. (2009). Latinos on Race and Ethnicity: Alcoff, Corlett, and Gracia. In S. Nuccetelli, O. Schutte, & O. Bueno (Eds.), A companion to latin american philosophy (pp. 269–282). Wiley Blackwell.

Bulatao, R. A., & Anderson, N. B. (2004). Understanding racial and ethnic differences in health in late life: a research agenda. Panel on race, ethnicity, and health in later life. National Research Council.

Burris, H. H., Wright, C. J., Kirpalani, H., Collins Jr, J. W., Lorch, S. A., Elovitz, M. A., & Hwang, S. S. (2020). The promise and pitfalls of precision medicine to resolve black–white racial disparities in preterm birth. Pediatric research, 87(2), 221–226.

Ceci, S., & Williams, W. M. (2009). Should scientists study race and IQ? Yes: the scientific truth must be pursued. Nature, 457(7231), 788–789.

Chitrala, K. N., Hernandez, D. G., Nalls, M. A., Mode, N. A., Zonderman, A. B., Ezike, N., & Evans, M. K. (2020). Race-specific alterations in DNA methylation among middle-aged African Americans and Whites with metabolic syndrome. Epigenetics, 15(5), 462–482.

Clemente, J. E., Pehrsson, C., Blaser, M. J., et al. (2015). The microbiome of uncontacted amerindians. Science Advances, 3(1), e1500183.

Corzett, C. C. (2019). Conserving Cultures: Preserving Humanity’s Microbial Heritage, ASM.org. Available at: https://asm.org/Articles/2019/November/Conserving-Cultures-Preserving-Humanity-s-Microbia (Accessed: 27 November 2021).

Deshpande, A. (2000). Does caste still define disparity? A look at inequality in Kerala, India. American Economic Review, 90(2), 322–325.

Durack, J., & Lynch, S. V. (2019). The gut microbiome: relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. Journal Of Experimental Medicine, 216(1), 20–40.

Duster, T. (2015). A post-genomic surprise. The molecular reinscription of race in science, law and medicine. The British journal of sociology, 66(1), 1–27.

Dutta, A., Mohapatra, M. K., Rath, M., Rout, S. K., Kadam, S., Nallalla, S., & Paithankar, P. (2020). Effect of caste on health, independent of economic disparity: evidence from school children of two rural districts of India. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(6), 1259–1276.

Fettweis, J. M., et al. (2014). Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology 160:2272–2282

Findley, K., Williams, D. R., Grice, E. A., & Bonham, V. L. (2016). Health disparities and the microbiome. Trends in microbiology, 24(11), 847–850.

Fortenberry, J. D. (2013). The uses of race and ethnicity in human microbiome research. Trends in microbiology, 21(4), 165–166.

Francomano, C. A. (2012). Victor A. McKusick and Medical Genetics among the amish. In K. R. Dronamraju, & C. A. Francomano (Eds.), Victor McKusick and the history of Medical Genetics (pp. 119–130). Springer New York.

Gupta, V. K., Paul, S., & Dutta, C. (2017). Geography, ethnicity or subsistence-specific variations in human microbiome composition and diversity. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 1162.

Galanter, J. M., et al. (2017). Differential methylation between ethnic sub-groups reflects the effect of genetic ancestry and environmental exposures. eLife, 6, e20532. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.20532

Gibbons, A. (2015). Ancient bacteria found in hunter-gatherer guts. Science, AAAS Available at: https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-bacteria-found-hunter-gatherer-guts (Accessed: 27 November 2021).

Gracia, J. J. (2017). Race and ethnicity. In N. Zack (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Race (pp. 180–190). Oxford University Press.

Graves, J. L. Jr. (2001). The emperor’s new clothes: Biological theories of race at the millennium. Rutgers University Press.

Gravlee, C. C. (2009). How race becomes biology: embodiment of social inequality. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139, 47–57.

Guthman, J. (2014). Doing justice to bodies? Reflections on food justice, race, and biology. Antipode, 46(5), 1153–1171.

Hardimon, M. O. (2013). Race concepts in medicine. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 38(1), 6–31.

Haslanger, S. (2000). Gender and race:(what) are they? (what) do we want them to be? Noûs, 34(1), 31–55.

Haslanger, S. (2005). “You mixed? Racial identity without racial biology.“ In Haslanger, S. & Witt, C. (Eds) Adoption matters: Philosophical and feminist essays. pp265-289.

He, Y., Wu, W., Zheng, H. M., Li, P., McDonald, D., Sheng, H. F., & Zhou, H. W. (2018). Regional variation limits applications of healthy gut microbiome reference ranges and disease models. Nature medicine, 24(10), 1532–1535.

Hochman, A. (2019). Race and reference. Biology & Philosophy, 34(2), 1–22.

Hoffman, K. L., Hutchinson, D. S., Fowler, J., Smith, D. P., Ajami, N. J., Zhao, H., & Daniel, C. R. (2018). Oral microbiota reveals signs of acculturation in mexican american women. PloS one, 13(4), e0194100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194100

Horvath, S., Gurven, M., Levine, M. E., Trumble, B. C., Kaplan, H., Allayee, H., & Assimes, T. L. (2016). An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome biology, 17(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1030-0

Hyman, R. W., Fukushima, M., Jiang, H., Fung, E., Rand, L., Johnson, B., & Giudice, L. C. (2014). Diversity of the vaginal microbiome correlates with preterm birth. Reproductive sciences, 21(1), 32–40.

Jasienska, G. (2009). Low birth weight of contemporary african Americans: an intergenerational effect of slavery? American Journal of Human Biology, 22, 16–24.

Jeffers, C. (2013). The cultural theory of race: yet another look at Du Bois’s “The conservation of Races”. Ethics, 123(3), 403–426.

Kalewold, K. H. (2020). Race and medicine in light of the new mechanistic philosophy of science. Biology & Philosophy, 35(4), 1–22.

Kaplan, J. M., & Winther, R. G. (2013). Prisoners of abstraction? The theory and measure of genetic variation, and the very concept of “race”. Biological theory, 7(4), 401–412.

Keller, E. F. (2017). Thinking about biology and culture: can the natural and human sciences be integrated?. The Sociological Review, 64(1_suppl), 26–41

Kitcher, P. (2007). Does’ race’have a future?.Philosophy and Public Affairs,293–317.

Kressing, F. (2012). : Screening indigenous peoples’ genes - the end of racism or postmodern bio-imperialism? In: Berthier, S.; Tolazzi, S.; Whittick, Sh. (Hrsg.), Biomapping or Biocolonizing?: Indigenous Identities and Scientific Research in the 21st Century. Amsterdam, New York, 117–136

Kronfeldner, M. E. (2009). Genetic determinism and the innate-acquired distinction in medicine. Medicine studies, 1(2), 167–181.

Kuzawa, C. W., & Sweet, E. (2009). Epigenetics and the embodiment of race: developmental origins of US racial disparities in cardiovascular health. American Journal of Human Biology: The Official Journal of the Human Biology Association, 21(1), 2–15.

Leavitt, P. A., Covarrubias, R., Perez, Y. A., & Fryberg, S. A. (2015). “‘Frozen in Time’: The Impact of Native American Media Representations on Identity and Self-Understanding.” Journal of Social Issues 71 (1): 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12095

Lee, C. (2009). “Race” and “ethnicity” in biomedical research: how do scientists construct and explain differences in health? Social science & medicine, 68(6), 1183–1190.

Lipphardt, V. (2012). Isolates and Crosses in Human Population Genetics; or, A Contextualization of German Race Science. Current Anthropology 53 (S5): S69–82. https://doi.org/10.1086/662574

Lipphardt, V. (2014). “Geographical distribution patterns of various Genes”: genetic studies of human variation after 1945. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 47, 50–61.

Lock, M. M., & Palsson, G. (2016). Can science resolve the nature/nurture debate?. John Wiley & Sons.

Ludwig, D. (2015). “Against the New Metaphysics of Race.” Philosophy of Science 82 (2): 244–65https://doi.org/10.1086/680487

Ludwig, D. (2019). How race travels: relating local and global ontologies of race. Philosophical Studies, 176(10), 2729–2750.

Lumpkins, C. Y., & Saint Onge, J. M. (2017). Reducing Low Birth Weight among African Americans in the Midwest: A Look at How Faith-Based Organizations Are Poised to Inform and Influence Health Communication on the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). Healthcare 5, no. 1: 6https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5010006

MacIntyre, D. A., Chandiramani, M., Lee, Y. S., Kindinger, L., Smith, A., Angelopoulos, N., & Bennett, P. R. (2015). The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a european population. Scientific reports, 5(1), 1–9.

Mallon, R. (2007). A field guide to social construction. Philosophy Compass, 2(1), 93–108.

Mansfield, B. (2012). Race and the new epigenetic biopolitics of environmental health. BioSocieties, 7(4), 352–372.

Mansfield, B., & Guthman, J. (2015). Epigenetic life: biological plasticity, abnormality, and new configurations of race and reproduction. cultural geographies, 22(1), 3–20.

Marks, J. (1995). Human Biodiversity. Aldine de Gruyter, 1995

Marks, J. (2017). Is science racist?. Polity Press.

Maroney, S. (2017). “Reviving Colonial Science in Ancestral Microbiome Research.”. Accessed 15 Dec 2021. https://microbiosocial.wordpress.com/2017/01/10/reviving-colonial-science-in-ancestral-microbiome-research/

M’charek, A. (2005). The Human Genome Diversity Project: an ethnography of scientific practice. Cambridge University Press.

Mehta, O., Ghosh, T. S., Kothidar, A., Gowtham, M. R., Mitra, R., Kshetrapal, P., & GARBH-Ini study group. (2020). Vaginal Microbiome of Pregnant Indian Women: Insights into the Genome of Dominant Lactobacillus Species.Microbial ecology, 80(2).

Meloni, M. (2016). From boundary-work to boundary object: how biology left and re-entered the social sciences. The Sociological Review, 64(1_suppl), 61–78.

Meloni, M. (2017). Race in an epigenetic time: thinking biology in the plural. The British Journal of Sociology, 68, 389–409.

Meloni, M., Moll, T., Issaka, A., & Kuzawa, C. W. (2022). A biosocial return to race? A cautionary view for the postgenomic era.American Journal of Human Biology,e23742.

Meloni, M., Williams, S., & Martin, P. (2016). The biosocial: sociological themes and issues. The Sociological Review, 64(1_suppl), 7–25.

Mills, C. (2000). ‘But what are you really?’ The Metaphysics of Race. In Light, A. & Mechthild, N. (Eds) Race, Class and Community Identity: Radical Philosophy Today. Humanity Books. pp23-51.

Neel, J. V. (1970). Lessons from a ‘Primitive’ People: Do Recent Data Concerning South American Indians Have Relevance to Problems of Highly Civilized Communities?. Science 170 (3960): 815–22https://doi.org/10.1126/science.170.3960.815

Nieves Delgado, A., & Baedke, J. (2021). Does the human microbiome tell us something about race? Humanit Soc Sci Commun, 8, 1–12.

Ohm, J. E. (2019). Environmental exposures, the epigenome, and african american women’s health. Journal of Urban Health, 96(1), 50–56.

Outlaw, L. T. (2014). If not races, then what? Toward a revised understanding of Bio-Social Groupings. Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, 35(1/2), 275–296.

Pálsson, G. (2007). Anthropology and the New Genetics. Cambridge University Press.

Paul, D. B. (2003). Darwin, social darwinism and eugenics. In G. Radick, & M. J. S. Hodge (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Darwin (pp. 219–245). Cambridge University Press.

Porras, A. M., & Brito, I. L. (2019). The internationalization of human microbiome research. Current opinion in microbiology, 50, 50–55.

Quin, C., & Gibson, D. L. (2020). Human behavior, not race or geography, is the strongest predictor of microbial succession in the gut bacteriome of infants. Gut microbes, 11(5), 1143–1171.

Rai, R. (2021). From colonial ‘mongoloid’to neoliberal ‘northeastern’: theorising ‘race’, racialization and racism in contemporary India.Asian Ethnicity,1–21.

Rampelli, S., Schnorr, S. L., Consolandi, C., Turroni, S., Severgnini, M., Peano, C., & Candela, M. (2015). Metagenome sequencing of the Hadza hunter-gatherer gut microbiota. Current Biology, 25(13), 1682–1693.

Ravel, J., Gajer, P., Abdo, Z., Schneider, G. M., Koenig, S. S., McCulle, S. L., & Forney, L. J. (2011). Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 1), 4680–4687.

Reardon, J. (2008). Race without salvation: beyond the science/society divide in genomic studies of human diversity. In B. A. Koenig, S. S. Lee, & S. S. Richardson (Eds.), Revisiting race in a genomic age (pp. 304–319). Rutgers University Press.

Reich, D. (2018). Who we are and how we got here: ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. Oxford University Press.

Richardson, S. S. (2011). Race and IQ in the postgenomic age: the microcephaly case. BioSocieties, 6(4), 420–446.

Richardson, S. S., & Stevens, H. (Eds.). (2015). Postgenomics: perspectives on biology after the genome. Duke University Press.

Risch, N., Burchard, E., Ziv, E., & Tang, H. (2002). Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome biology, 3(7), 1–12.

Roberts, D. (2011). Fatal invention: how science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century. New Press/ORIM.

Roberts, D. (2016). The ethics of biosocial science. The Tanner lectures on human values

Rosenberg, N. A., Pritchard, J. K., Weber, J. L., Cann, H. M., Kidd, K. K., Zhivotovsky, L. A., & Feldman, M. W. (2002). Genetic structure of human populations. Science, 298(5602), 2381–2385.

Rosenberg, E., & Zilber-Rosenberg, I. (2019). The hologenome concept of evolution: Medical implications.Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal, 10(1).

Ross, M. C., Muzny, D. M., McCormick, J. B., Gibbs, R. A., Fisher-Hoch, S. P., & Petrosino, J. F. (2015). 16S Gut Community of the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort. Microbiome 3 (1): 7https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0072-y

Saban, K. L., Mathews, H. L., DeVon, H. A., & Janusek, L. W. (2014). Epigenetics and social context: implications for disparity in cardiovascular disease. Aging and disease, 5(5), 346.

Saldaña-Tejeda, A. (2018). Mitochondrial mothers of a fat nation: race, gender and epigenetics in obesity research on mexican mestizos. BioSocieties, 13, 434–452.

Saldaña-Tejeda, A., & Wade, P. (2018). Obesity, race and the indigenous origins of health risks among mexican mestizos. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41, 2731–2749.

Salihu, H. M., Das, R., Morton, L., Huang, H., Paothong, A., Wilson, R. E., & Marty, P. J. (2016). Racial differences in DNA-methylation of CpG sites within preterm-promoting genes and gene variants. Maternal and child health journal, 20(8), 1680–1687.

Saulnier, K. M., & Dupras, C. (2017). Race in the postgenomic era: social epigenetics calling for interdisciplinary ethical safeguards. American Journal of Bioethics, 17, 58–60.

Schiebinger, L. (1990). The anatomy of difference: race and sex in eighteenth-century science. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 23(4), 387–405.

Schnorr, S. L., Candela, M., Rampelli, S., Centanni, M., Consolandi, C., Basaglia, G., & Crittenden, A. N. (2014). Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nature communications, 5(1), 1–12.

Serrano, M. G., Parikh, H. I., Brooks, J. P., Edwards, D. J., Arodz, T. J., Edupuganti, L., & Buck, G. A. (2019). Racioethnic diversity in the dynamics of the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy. Nature medicine, 25(6), 1001–1011.

Sesardic, N. (2010). Race: a social destruction of a biological concept. Biology & Philosophy, 25(2), 143–162.

Singh, G., Morrison, J., & Hoy, W. (2019). DOHaD in Indigenous Populations: DOHaD, Epigenetics, Equity and Race. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 10, no. 1: 63–64https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174419000023

Smedley, A., & Smedley, B. D. (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American psychologist, 60(1), 16.

Smits, S. A., Leach, J., Sonnenburg, E. D., Gonzalez, C. G., Lichtman, J. S., Reid, G., & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2017). Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science, 357(6353), 802–806.

Song, M. A., Brasky, T. M., Marian, C., Weng, D. Y., Taslim, C., Dumitrescu, R. G., & Shields, P. G. (2015). Racial differences in genome-wide methylation profiling and gene expression in breast tissues from healthy women. Epigenetics, 10(12), 1177–1187.

Spencer, Q. (2013). Biological theory and the metaphysics of race: a reply to Kaplan and Winther. Biological Theory, 8(1), 114–120.

Spencer, Q. (2015). Philosophy of race meets population genetics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 52, 46–55.

Stotz, K. (2008). The ingredients for a postgenomic synthesis of nature and nurture. Philosophical Psychology, 21(3), 359–381.

Suárez-Díaz, E. (2014). Indigenous populations in Mexico: medical anthropology in the work of Ruben Lisker in the 1960s. Studies in history and philosophy of Science Part C: studies. in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 47, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2014.05.011

Sullivan, S. (2013). Inheriting racist disparities in health: epigenetics and the transgenerational effects of white racism. Critical Philosophy of Race, 1(2), 190–218.

TallBear, K. (2013). Native american DNA: tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science. University of Minnesota Press.

TallBear, K. (2007). Narratives of race and indigeneity in the Genographic Project. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 35(3): 412–424

Tito, R. Y., Knights, D., Metcalf, J., Obregon-Tito, A. J., Cleeland, L., Najar, F., & Lewis, C. M. Jr. (2012). Insights from characterizing extinct human gut microbiomes. PloS one, 7(12), e51146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051146

Van der Toorn, J. E., Cepeda, M., Kiefte-de Jong, J. C., Franco, O. H., Voortman, T., & Schoufour, J. D. (2020). Seasonal variation of diet quality in a large middle-aged and elderly dutch population-based cohort. European journal of nutrition, 59(2), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01918-5

Vick, A. D., & Burris, H. H. (2017). Epigenetics and health disparities. Current epidemiology reports, 4(1), 31–37.