Abstract

Transphobia is an under-examined but important type of prejudice to study in Polish culture. Poland is a country where a majority of transgender people feel discriminated against. There is a need for a more evidence-based measures for researchers and practitioners to better understand transphobia. The main purpose of the present three studies (n = 300 participants for each study) was to validate the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (GTS; Hill and Willoughby 2005) and the Transphobia Scale (TS; Nagoshi et al. 2008) in Polish culture and to identify the possible psychological and demographic factors that matter in forming attitudes toward transgender individuals. The results confirm that Polish versions of both the GTS and the TS are reliable instruments to measure attitudes toward transgender individuals. Moreover, the studies revealed that both traditional and modern homonegativity, right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, religious fundamentalism, attitudes toward gender roles, and biological and cultural beliefs about the origins of gender differences were significant predictors of transphobia. As in previous studies, men were more prejudiced toward gender nonconformists in comparison to women. These studies contribute well-adapted tools for measuring transphobia and data-driven collection of significant predictors of transphobia.

Similar content being viewed by others

The present paper reports the validation of Polish versions of two recently developed and widely used measurements of transphobia: the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (GTS; Hill and Willoughby 2005) and the Transphobia Scale (TS; Nagoshi et al. 2008). Transphobia is defined as a prejudice against transgender individuals (Nagoshi et al. 2018) or, more specifically, as a fear and emotional disgust toward individuals who do not conform to society’s gender expectations (Hill and Willoughby 2005). Transgender individuals act against the traditional view of gender identity according to which gender is determined by biological factors and assigned at birth. Whereas many studies have been devoted to attitudes toward lesbian and gay people (Górska et al. 2017; Morrison and Morrison 2011; Piumatti 2017), who are still the targets of discrimination in many countries (Štulhofer and Rimac 2009; van den Akker et al. 2013; Zick et al. 2011), there is still less research concerning transgender people. Transgender individuals, like lesbian and gay people, also cross gender boundaries, but in a different manner, which is much more aligned with gender identity than with sexual orientation.

The term transgender refers to individuals whose gender identity is different from the gender they were assigned at birth (National Center for Transgender Equality 2016). However, “transgender person” is an umbrella term (Billard 2018). According to Śledzińska-Simon (2013), the prefix “trans-” is applied toward many different categories of people including those who identify as transsexual, transgender, transvestite, androgynous, queer, asexual, or cross-dresser. In the present paper, it denotes transsexual people (those who try to change their biological gender to the gender with which they identify using advanced medical intervention), transgender individuals (those who adapt their body to the gender with which they identify with little medical intervention), cross-dressing people (those who use external cues, such as clothes, to manifest their temporary belongingness to the other gender), and feminine men or masculine women—that is, all those who violate cultural norms of gender identity and gender roles. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals also seem to belong to this group because they are perceived as gender transgressors (Fassinger and Arseneau 2007). Nevertheless, some researchers have pointed out that attitudes toward transgender individuals, as well as their discriminatory experiences, differ from those that are associated with lesbian and gay people (Fassinger and Arseneau 2007; Worthen 2013). Although they are included in the LGBT acronym (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender), transgender individuals and attitudes toward them should be analyzed separately (Worthen 2013).

Prejudice and discrimination against transgender individuals are well-established phenomena. A report from the National Transgender Discrimination Survey under the meaningful title “Injustice at Every Turn” (Grant et al. 2011) brought to light the prevalence of discrimination against transgender people in the United States. Their study showed that transgender individuals experience stigmatization in many public spheres including education, employment, and healthcare. Simultaneously, as many as 50% of the 6,456 individuals in the studied sample claimed that they were harassed by someone at work, and 32% of respondents reported having presented or feeling forced to present in the wrong gender to keep their jobs. Moreover, 71% of participants admitted that they hid their gender or transition to avoid being discriminated against.

A similar situation is observed in the European Union countries. The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights survey (2013), which was conducted in 28 countries, revealed that 46% of the 6,771 transgender individuals surveyed felt discriminated against, and 28% were attacked or threatened with violence more than three times in the year preceding the survey. Although the survey showed important differences among countries, it is worth noting that even in the least conservative countries like Sweden or Finland (Donaldson et al. 2017), almost 40% of participants admitted experiencing discrimination and harassment because of being an LGBT individual.

Poland seems to be an interesting country against this background. On the one hand, it was Poland where a transsexual person—Anna Grodzka—became a member of Parliament for the first time in Europe. On the other hand, survey data of a representative sample of 1,000 persons revealed, that the majority of Poles (76%) considered homosexuality as immoral (Zick et al. 2011), whereas the Polish defense minister has called an LGBT pride parade a “parade of sodomites” (Chrzczonowicz 2018, para. 8). The number of transgender people in Poland has been estimated as less than 1% of the population (Zucker and Lawrence 2009); however, it must be noted that these estimates include only individuals who sought biological gender reassignment procedures so they do not capture all subtypes of transgender individuals (Kłonkowska 2015). A study by Antosz (2012) showed that among many social groups that might be the object of discrimination in Poland, transsexual individuals, according to a measurement conducted by an aggregated social distance scale, are one of the most negatively assessed groups.

Recently, a comprehensive study of the social situation of 10,704 LGBTA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and ally) people in Poland was published, of which 7.2% were transgender individuals (Świder and Winiewski 2017). When asked about their experiences with social institutions, 27.7% of transgendered individuals declared that they experienced unequal treatment from healthcare professionals, whereas 46.5% claimed that the same had happened in public offices and places. Of the transgender participants, 78.6% experienced at least one of verbal, physical, or sexually aggressive acts. All these harmful experiences seem to translate into mental health functioning. When asked to evaluate the quality of their life, 42.4% of transgender people assessed it negatively, and about 72% of them admitted considering suicide during the last year (Świder and Winiewski 2017).

In the present study, we focused on two commonly used scales for measuring attitudes toward transgender individuals originally developed for use in Western culture. In doing so, we tested these available measurements of transphobia in a non-native English-speaking country. The level of transphobia in a specific country might be influenced by the cultural values that translate into more or less accepting attitudes toward individuals who cross gender boundaries. A great illustration of this idea was a study by Donaldson et al. (2017), who showed how attitudes toward gay and lesbian individuals are shaped both by the individual and by predictors for the country of residence. On the one hand, male gender, older age, high religiosity, high conservative values, and low openness to change were positive predictors of homonegativity. On the other hand, at the country level, high conservativism and fewer civil rights were positively associated with prejudice toward lesbian and gay people. The social and legal situation of sexual minorities in many European countries is rather well recognized; a demarcation line indicates that in Western countries, more permission for the civil rights of people who are lesbian or gay is observed when compared with Eastern and Central European countries (Štulhofer and Rimac 2009). According to the ILGA-Rainbow Europe Index Map (2019), Poland ranks among the countries with the most discrimination laws and policies targeting LGBT individuals, which influences attitudes toward lesbian and gay people (van den Akker et al. 2013) and, due to well-established parallelism (Nagoshi et al. 2008), toward transgender individuals.

Gender Issues in a Polish Context

Attitudes toward gender nonconformists in Poland are shaped by norms regarding gender roles, the conception of the family, and the influence of the Polish Catholic Church (Golebiowska 2017). Poland, as an ex-communist society, is more oriented toward survival and traditional values (Inglehart and Baker 2000), which counts in explaining cross-national differences in attitudes about LGBT individuals (Inglehart and Baker 2000; Inglehart et al. 2002). Survivalist-oriented nations that concentrate on economic and physical security are low in support for both gender equality and tolerance toward outgroups. Traditionally-oriented nations emphasize the role of God in their lives and attach special importance to the family.

In the case of gender egalitarianism, Poland ranks 42nd of 149 countries in the world in the Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum 2018), and this position is stable since 2006 (44th of 115 countries). Some researchers pointed out that although values and attitudes toward family and work are still changing after the political transformation in Poland, gender roles seem to still be strongly aligned with traditional features (Siemieńska 2008). This statement found confirmation in the study of Donaldson et al. (2017), who showed that social conservatism in Poland, defined as an adherence to traditional ideology, obtained a score of 4 of 5 (where 5 denotes the highest level of this country-level variable). Similarly, a study by Treas and Tai (2016) showed that Poland, like other post-socialist countries, is characterized by low gender egalitarianism. Egalitarian values are related to higher openness for diversity and are associated with lower prejudice toward gender nonconformists (Donaldson et al. 2017; Schwartz 2006). In less egalitarian cultures, the dichotomy between the sexes is regularly highlighted (Schwartz 2006), which causes people to try to avoid cross-sex behaviors (Żadkowska et al. 2018).

Regarding the specificity of Poland in gender-related issues, what might be crucial is a special position of the Catholic Church, which led some to equate being Polish with being Catholic (Heinen and Portet 2009). Analyzing data from 1999 to 2010 from the World and European Values Survey, Joshanloo and Weijers (2016) showed that Poles strongly identified with their religion and God (“importance of God” = 8.29 on a 10-point Likert scale with 10 denoting “very important”) and declared high frequency of religious practice (6.05 on an 8-point Likert scale with 8, after reversal, denoting “more than once a week”).

On the one hand, Catholic values are inherently associated with respect and openness toward all humans. This message was highlighted in 2016 in the social campaign “Let us give you a sign of peace” organized by LGBT organizations with companionship of some representatives of the Catholic Church and its associations (Chmielewska 2016). On the other hand, analyses of the statements of Catholic Church representatives in the media (Odrowąż-Coates 2015) showed that “gender” is presented as an ideology that destroys the traditional family and leads to divorce, abortion, sexualization of children, and other negative consequences at the societal and individual levels. Catholic religiosity predicts more sexism (Glick et al. 2002), which stresses the differentiation between males and females together with gender role dichotomization and serves as an ideology that allows the maintenance of gender inequality (Glick and Fiske 2001). The effect of religiosity on benevolent sexism was mediated by traditional norms and values in which females and males are appreciated in their stereotypical domains (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak 2014). This might explain why Polish men and women presented higher sexist attitudes than their counterparts in the United States (Forbes et al. 2004) or even South Africa (Zawisza et al. 2015).

Genderism and Transphobia Scale (GTS)

The GTS, developed by Hill and Willoughby (2005), originally included three subscales referring to emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of attitudes toward transgender individuals, namely transphobia, genderism, and gender bashing. Transphobia was defined as an emotional disgust toward transsexual, transgender, and cross-dressing individuals as well as feminine men and masculine women. Genderism is a cultural belief that reinforces the negative evaluation of gender nonconformists and boils down to the belief that those individuals are pathological. Finally, the subscale of gender bashing refers to violent and assaulting behaviors toward transgendered individuals. Validation studies by Hill and Willoughby (2005) showed that all three subscales of the GTS were highly internally consistent; however, strong intercorrelation between genderism and transphobia (r = .85, p = .01) was found, which suggested that there was insufficient discriminant validity between these two subscales. Together with the results of principal components analysis, these were the premises for deciding to reduce the scale to a two-factor solution (genderism/transphobia and gender bashing), which together accounted for 60% of the variance and was confirmed in further studies (Tebbe et al. 2014).

Previous studies have revealed the positive relation between GTS score and homophobia (Costa and Davies 2012; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Macapagal 2013), traditional beliefs about gender roles (Hill and Willoughby 2005), hostile and benevolent sexism (Carrera-Fernández et al. 2014), social dominance orientation, aggressiveness, and the need for closure (Tebbe et al. 2014). Many studies also have confirmed that men scored higher than women did on transphobia (Carrera-Fernández et al. 2014; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Macapagal 2013; Willoughby et al. 2010; Winter et al. 2008).

Transphobia Scale (TS)

The Transphobia Scale is a nine-item tool that measures prejudice toward transgender individuals (Nagoshi et al. 2008). It is a one-dimensional scale with high internal consistency (α = .82), which explains 44% of the variance. Studies have revealed that transphobia measured by the TS was positively associated with homophobia, right-wing authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, and ambivalent sexism (Makwana et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2008, 2018). Other studies using the TS have shown that transphobia was positively associated with the need for closure (Makwana et al. 2018; Tebbe and Moradi 2012), social dominance orientation, and traditional gender role beliefs (Makwana et al. 2018). As in the case of the GTS, men scored higher on the TS than did women (Makwana et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2008, 2018; Tebbe and Moradi 2012), and this pattern of gender differences was also obtained among gays and lesbians (Warriner et al. 2013).

The Present Studies

The present three studies aimed at validating the GTS and TS in Poland where, according to our knowledge, no comprehensive measurement of transphobia has been done. There is one study in which a dedicated tool was prepared for the measurement of transphobia (Antoszewski et al. 2007), but this instrument refers mainly to knowledge about the definition and etiology of transsexualism (e.g., “Does transsexualism have a genetic basis?”) as well as the rights that participants would grant to transsexual individuals (e.g., “Should transsexuals have the right to marry?”). Therefore, their study measured only one cognitive component of attitudes toward transsexual people and did not capture the remaining affective and behavioral aspects of such attitudes.

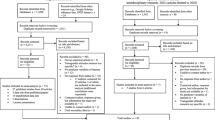

We designed Study 1 to evaluate the factor structure of the GTS and TS using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Additionally, in Study 1, we evaluated the validity of both instruments by testing the associations of GTS and TS scores with traditional and modern prejudice toward lesbian and gay people. In Study 2, we undertook further evaluation of both measurements by analyzing the relations of prejudice with right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and religious fundamentalism as expressions of social conventionalism, which, according to the three-component model of prejudice toward gender nonconformists, drives prejudice toward transgender individuals (Nagoshi et al. 2008). Study 3 aimed at verifying the associations between transphobia and attitudes toward gender roles as well as beliefs about the biological and cultural origins of gender differences. The theoretical background for choosing these psychological correlates was also the three-component model of gender-based prejudice (Nagoshi et al. 2008, 2018), according to which prejudice toward transgender individuals is motivated by the fear of any expressed deviations from a male and female conventional social identity. All psychological variables measured in our study might be treated as an expression of a “two sexes and two genders only” presumption as a core statement that drives transphobia.

In all three studies, various demographic factors were controlled for, namely gender, age, education, and size of locality (Studies 1–3), religiousness (Studies 2 and 3), and sexual orientation (Study 3). Using a hierarchical regression analysis allowed us to assess the unique contribution of all psychological factors in transphobia beyond the diversity resulting from the demographic variables. Hierarchical regression analysis is a widely used statistical framework for analyzing data, and it is particularly useful when there is an expectation that particular confounding effects (e.g., important sociodemographic characteristics) might affect the results.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 was twofold. First, we aimed to evaluate the factor structure of Polish-language versions of the GTS and TS. Using CFA, we tested the two-factor solution in the case of the GTS (Hill and Willoughby 2005; Tebbe et al. 2014) and the one-factor structure of the TS (Nagoshi et al. 2008). Secondly, we assessed the relations between transphobia and traditional (Morrison et al. 1999) and modern homonegativity (Morrison and Morrison 2003). Previous studies have clearly shown a strong relationship between prejudices toward transgender, lesbian and gay people (Hill and Willoughby 2005; Macapagal 2013; Nagoshi et al. 2008); however, no distinction between these two types of anti-gay and lesbian prejudice has been made in a single study. Traditional (old-fashioned) homophobic prejudice manifests itself by believing that same-sex relationships are sinful and unnatural and that homosexuality is related to pedophilia and thus is a pathological expression of human sexuality (Górska et al. 2017). In contrast, modern homonegativity reflects more covert prejudice toward sexual minorities. It manifests itself in convictions that lesbian and gay individuals’ claims for social change are illegitimate, discrimination against them no longer exists, and that gays and lesbians overemphasize the meaning of sexual orientation (Górska et al. 2017). We hypothesized that both traditional and modern homonegativity would be related to transphobia (Hypothesis 1) because all three have the same homophobic component (Górska et al. 2017; Nagoshi et al. 2008).

Considering the results of previous studies (Carrera-Fernández et al. 2014; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Makwana et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2008; Willoughby et al. 2010), we also predicted that men would score higher on transphobia than would women (Hypothesis 2). This well-established gender difference in attitudes toward gender nonconformists has its roots in the precariousness of manhood and the antifemininity mandate (Falomir-Pichastor et al. 2010; Vandello and Bosson 2013), both of which postulated as cross-cultural phenomena (Bosson and Michniewicz 2013; Gilmore 1990). Masculinity, compared with femininity, is a precarious social status that is “hard won and easily lost” (Vandello and Bosson 2013, p. 101). Losing one’s own masculinity might be a result of expressing feminine traits and behaviors by men who are culturally prohibited from showing such manifestations. Men who display feminine characteristics are viewed as being gay (McCreary 1994), whereas antifemininity counted the most in predicting antigay prejudice (Martínez et al. 2015). The study showed that the higher endorsement of antifemininity, the higher perceived dissimilarity from gay men and subsequently more prejudice toward them. Men invest strong efforts in presenting themselves as masculine, and manifesting prejudice toward gender nonconformists might be one of many ways to prove one’s own masculinity (Rivera and Dasgupta 2018).

Method

Participants

The participants were 300 Polish adults between 18 and 50 years-old (M = 29.35, SD = 9.82). Women constituted exactly 50% of the sample. The study was conducted among undergraduate students from various universities in Warsaw. To go beyond the college student sample, the sampling procedure was expanded to other adults who agreed to participate in the study. Regarding education, 61.7% (n = 185) had a university education, 36.3% (n = 109) had high school education, and the remaining 2% (n = 6) had basic or vocational education, χ2(3) = 315.09, p < .001. As to their residence, 31.0% (n = 93) lived in a city (over 500,000 residents), 24.3% (n = 73) in medium-sized towns, 22.7% (n = 68) in small towns (up to 50,000 residents), and 22.0% (n = 66) in the countryside, χ2(3) = 6.11, p = .107. No missing data were identified for either the GTS or TS scales. Thus, no participants were excluded from the study. No special attentions checks were used; however, we monitored the levels of variance for particular subscales to identify the participants answering the questions in an identical way (i.e., the same answer across scales).

Procedure and Measures

Participants were tested in small groups in classrooms or dormitories, or they individually filled out the paper-and-pencil questionnaires. Participants were informed about the purpose, nature, and anonymity of the study and that they could refuse to participate or stop without giving any reason at any time. Individuals who volunteered to participate in the study were given a booklet with a demographic metric presented first, and subsequently measures of transphobia and homonegativity were given. An ethics approval was not required for our study as per applicable institutional guidelines and regulations, and the informed consent of the participants was implied through survey completion. Participants were not remunerated.

Genderism and Transphobia Scale

We used a Polish version of the GTS (Hill and Willoughby 2005) in the study. First the questionnaire was translated into Polish and back-translated into English by two bilingual experts. Then a pilot study was conducted (n = 31), which allowed us to discuss and examine the clarity of items. The final version was approved by the first author of the GTS. The scale comprises 32 items, and in its original version, it uses a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). The Polish version of the GTS also uses a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). Higher averaged scores indicate a higher level of prejudice toward transgender individuals. (The Polish translation of this scale is available in the online supplement.)

Transphobia Scale

We used a Polish version of the TS (Nagoshi et al. 2008) in the study. As in the case of the GTS, the questionnaire was translated into Polish, back-translated into English, subjected to linguistic analysis in the same pilot study, and approved by the author of the TS. The scale consists of nine 7-point Likert-scale items from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). Higher averaged scores indicate a higher level of prejudices toward transgender individuals. (The Polish translation of this scale is available in the online supplement.)

Homonegativity Scale

The Homonegativity Scale (Morrison et al. 1999) measures traditional (old-fashioned) prejudices toward lesbian and gay people. A Polish version was adapted by Górska et al. (2017) and consists of a four-item measure using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). A sample item is: “Gay people should not be allowed to work with children.” Responses were averaged across items so that higher scores indicate greater homonegativity. In the present study, the instrument had good internal consistency (α = .77).

Modern Homonegativity Scale

The Modern Homonegativity Scale (Morrison and Morrison 2003) measures subtle and covert prejudice toward lesbian and gay people and was adapted in Poland by Górska et al. (2017). The Polish version is an 11-item measure using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). A sample item is: “Gay people seem to focus on the ways in which they differ from heterosexual people and ignore the ways in which they are the same.” Responses were averaged across items so that higher scores indicate greater modern homonegativity. The instrument has good internal consistency in the present study (α = .89).

Sociodemographic Variables

Demographic information included gender (male, female), age, education (university, high school, vocational, primary), and size of the locality (city, medium-sized town, small town, countryside).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To check whether the structure proposed by the authors of the GTS and the TS can be confirmed in the Polish sample, we ran a CFA. CFA is a widely used statistical technique that determines whether the data fit a measurement model hypothesized by the original theoretical and empirical work previously proposed (Fox 1983; Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). The CFA requires all missing data to be taken care of to make use of modification indices. However, there was no need to use any computational techniques for missing data replacement (e.g., expectation maximization) because there were no missing data present either for the GTS or the TS. All the assumptions for CFA were met (multivariate normality, missing data, sample size, occurrence of outlying cases, absence of multicollinearity, and singularity).

The CFA results confirmed the two-factor structure of the GTS (see Table 1a). Both models (1a and 1b) showed very good performance. The basic model (1a—simple CFA without adjustments based on covariance errors) already fit quite well. Although the Chi-square test was significant, the other model’s fit indices suggested an acceptable fit. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was at the acceptable level (criteria of .6–.8, or at least below .1), the incremental fit index (IFI) was not far from the recommended .95, and the ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom was within the interval of 2 and 3 (Schreiber et al. 2006). All regression paths were significant (p < .05) with high values ranging from .45 to .81 (for standardized coefficients). However, the p of close fit (PCLOSE) value (below the recommended .5) and RMR value (above the recommended .08) suggested that some improvements to Model 1a were possible.

We decided to apply some adjustments (although not all were possible to avoid unnecessary overfit) based on modification indices to improve the basic model. In this way, a nearly a perfect fit was achieved (see Table 1a). The model with adjustment was still significant, but other indices indicated a very good fit. This time, even the PCLOSE value (above .05) was acceptable. The IFI was still a bit below the value of .95, and RMR was above .08, but all other indices indicated a very good fit. The RMSEA even dropped and was much below the recommended 1.0, and the ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom was almost perfect. The new model was also improved based on the Akaike information criterion values (drop in value between Model 1a and Model 1b). All the regression paths were high and significant (p < .05), ranging from .43 to .81 (standardized coefficients). The intercorrelation between the GTS–GB (gender bashing) and GTS–TG (transphobia/genderism) subscales was at the acceptable level, r(300) = .67, p < .001 (much below the recommended r = .85) and did not suggest discriminative validity issues. Cronbach’s alpha for the GTS–GB subscale was .78 whereas alpha for the GTS–TG subscale was .95. Altogether, the two-dimensional structure of the GTS was confirmed by statistical procedures. (A graph with the factor loadings of all the items to the assigned factors can be found in the online supplement, Fig. 1 s.)

In the case of the TS, the structure proposed by the authors (this time, one-factor structure) was also confirmed. For both models (basic [2a] and with modification indices [2b]), the χ2 test was significant (see Table 1b), but all other indications of fit (especially for the model with adjustments [2b]) suggested acceptable (Model 2a) or very good (Model 2b) performance. According to the basic Model 2a, the IFI value was very good, but other indices were around acceptable values, although they were not perfect (too high ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom, a bit too high RMSEA, too low PCLOSE, too high RMR) and suggested that a model could be improved. After adding some adjustments based on modification indices (not all of them, though, because our goal was not to overfit a model), a nearly perfect fit was achieved for Model 2b. The ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom was within an interval of 2 and 3, RMSEA was below .1 or even below .08, PCLOSE was above the recommended .05, RMR was lower but still a bit high, IFI was perfect, and the Akaike value dropped in comparison to Model 2a. All the regression paths were significant (p < .05) and ranged from .55 to .85. Cronbach’s alpha was .91. Overall, the one-factor structure was confirmed. (A graph with the factor loadings of all the items to the assigned factor can be found in the online supplement, Fig. 2 s.)

Because the results of the CFA were positive for both scales, we decided to use the indices that were based on mean values and reflected the structure proposed by the authors in the further analyses. To test our hypotheses, we inspected the study variables using descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and hierarchical regression analyses.

Descriptive Statistics

The basic descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the study variables are presented in Table 2 (and separately for women and men in Table 1s of the online supplement). According to the results, the GTS–GB (Gender Bashing), GTS–TG (Transphobia/Genderism), and TS were not related to sociodemographic characteristics such as age, size of locality, and education (except for small but significant negative coefficients for GTS–TG and TS). Participants’ gender, however, played a significant role for all three dependent variables. Men presented higher levels of GTS–GB (Mmen = 2.23, SDmen = 1.05, Mwomen = 1.91, SDwomen = .89, t(289.39) = 2.80, p = .005, d = .32), GTS–TG (Mmen = 4.34, SDmen = 1.19, Mwomen = 3.66, SDwomen = 1.29, t(289) = 4.74, p < .001, d = .55), and TS (Mmen = 4.77, SDmen = 1.37, Mwomen = 4.30, SDwomen = 1.56, t(289) = 2.78, p = .006, d = .32) than women, which also coexisted with higher traditional, r(300) = −.12, p = .32 (women coded as 1), and modern Homonegativity, r(300) = −.24, p < .001. The correlation coefficients in Table 2 should be interpreted with some caution because GTS–GB had a skewed distribution.

Regression Analyses

To check whether the magnitude of gender bashing, transphobia/genderism, and transphobia could be predicted based on sociodemographic factors and, more importantly, based on traditional and modern homonegativity, we performed a hierarchical regression analysis. All variables were screened (missing data, normality, outlying cases, etc.) before the main analysis to examine whether the requirements for multiple regression analysis were met. No significant departures were found except for the GTS–GB distribution. GTS–GB was positively skewed, and after careful consideration of different possibilities (elimination of a few outlying cases, sqrt transformation, log or inverse transformation) we decided to apply log 10 transformation, which improved the distribution of our dependent variable. We also checked whether the data fulfilled the necessary assumptions (linearity, lack of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity).

According to the results, all regression models were significant (see Table 3). Men presented higher levels of GTS–GB and GTS–TG and transphobia measured with the TS in comparison to women. However, some of these results diminished after inclusion of homonegativity in traditional and modern form. In the second block, men were characterized by higher levels of GTS–TG in comparison to women, but they did not present higher levels of GTS–GB or transphobia (TS). Better education was related to lower levels of GTS–TG and TS, but only in the first block. The effects disappeared after adding homonegativity in the second step. Size of locality was related negatively to GTS–TG levels, but again only in the case of the first step. According to the final results, homonegativity in traditional form was a significant predictor of GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS, whereas homonegativity in its modern form was a significant predictor of GTS–TG and TS but not GTS–GB. All the final results were significant after controlling for typical sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education, and size of locality).

Discussion

Study 1 confirmed the two-factor structure of the GTS (Hill and Willoughby 2005; Tebbe et al. 2014) and the one-factor solution as adequate for the TS (Nagoshi et al. 2008). It must be noted that some of the earlier studies regarding the GTS revealed some inconsistencies in factor solutions, showing for example a five-factor structure in the Chinese context (Winter et al. 2008) or the original three-factor model as the most adequate among Filipinos (Willoughby et al. 2010). As Tebbe et al. (2014) pointed out, these were due to cross-cultural differences across samples and different statistical procedures that were applied to data analyses. Our study, however, confirmed that the two-factor solution, with genderism/transphobia as the cognitive and emotional component and gender bashing as the behavioral component in the GTS, adequately represents the structure of prejudice toward transgender people in Poland. Both the GTS and the TS were characterized by high internal consistency.

According to Hypothesis 1, both traditional and modern homonegativity were significant predictors of transphobia, as shown by the results after controlling for demographic variables included in our study. Although prejudice toward lesbian and gay people has been established as a key correlate of transphobia in previous studies (Carrera-Fernández et al. 2014; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Nagoshi et al. 2008), the present study is the first known time that these two forms of homonegativity have been considered simultaneously. Traditional and modern homonegativity differ in terms of the basis of anti-homosexual prejudice. Traditional homonegativity (TH) is rooted in religious and moralistic premises, whereas modern homonegativity (MH) concentrates on a critique of the political activity of lesbian and gay people. Thus, although conceptually distinct (Górska et al. 2017), both types of homonegativity predicted transphobia in a similar way, which is probably due to the common homophobia component (Górska et al. 2017). Although transgenderism is mainly a matter of gender and gender identity, it also contains strong associations with sexual orientation (Gagné et al. 1997), at least among heterosexual people (Kitzinger 2005).

However, one interesting result requires a comment, namely that gender bashing was predicted only by traditional but not modern homonegativity. The gender-bashing subscale of the GTS refers mainly to the readiness to use violence toward transgender people, a behavior that is rather unaccepted in normative populations (Dominiak-Kochanek et al. 2018). Traditional homonegativity includes an overtly hostile belief about the inferiority of lesbian and gay individuals (Górska et al. 2017), which is not the case in modern prejudice. The positive relationship between GTS–GB and TH indicate that when prejudice toward gender nonconformists is based on moralistic and religious views, it might imply an eagerness to assault and harass transgender individuals. These results are consistent with a three-component model of gender nonconformity prejudice (Nagoshi et al. 2008), which stresses social conventionalism as the key factor of prejudice toward gender nonconformists. Among two forms of homonegativity, it is the old-fashioned one that expresses adherence to rigid conventional norms and values, including religious conviction about acceptable sexual and gender behaviors; it was established earlier that social conventionalism is related to a higher propensity for and acceptance of aggression in interpersonal and social relationships (Benjamin 2016; Besta et al. 2015).

Hypothesis 2 stated that men would reveal a higher level of transphobia than women. This gender difference was seen both in the TS and both GTS subscales. However, entering traditional and modern homonegativity into the regression models made only the gender difference in genderism/transphobia remain statistically significant, probably because its initial regression coefficient had a higher value than those related to GTS–GB and TS. These results showed that even if men are more prone than women are to manifest higher prejudice toward transgender individuals, it is mainly their homonegativity that is responsible for the effect.

Study 2

The aim of Study 2 was to test the associations between transphobia and socio-ideological attitudes, namely right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), social dominance orientation (SDO), and religious fundamentalism (RF). RWA and RF are specified in the three-component model of gender nonconformity prejudice (Nagoshi et al. 2008) as key factors of social conventionalism, which drives prejudice toward LGBT individuals.

RWA is conceptualized as a complex of three social attitude dimensions, namely conventionalism, authoritarian submission, and authoritarian aggression (Duckitt et al. 2010). SDO is defined as a preference for group-based hierarchy and social inequality (Pratto et al. 1994). Both RWA and SDO can explain individual differences in prejudice related to gender, sexual orientation (Meeusen and Dhont 2015; Whitley and Lee 2000), and transphobia (Makwana et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2008; Tebbe et al. 2014; Willoughby et al. 2010). Individuals scaled higher on RWA maintain a traditional view of social order and oppose any changes in the socio-cultural status quo, whereas those higher on SDO prefer clear social hierarchy in which some groups are superior to others. Transgender individuals break the traditional social order by acting against the binary view of gender, and they might be perceived as threatening to social order and ingroup identity—in this case, gender identity.

Also, religiousness and RF—conceptualized as a strong adherence to one’s own religion, together with a rigid and inflexible conviction that only this religion is correct (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992)—plays a role in shaping attitudes toward gender nonconformists (Hunsberger 1996; Whitley 2009). A large study conducted in the United States showed that evangelical Christians felt less comfort in contact with transgender individuals, believed more in gender as a dichotomous category, and affirmed less intrinsic value to transgender persons when compared with nonreligious participants (Kanamori et al. 2017). Other studies showed that Catholics scored higher on the GTS than non-religious persons (Scandurra et al. 2017), whereas self-identifying religiosity was a positive predictor of transphobia (Norton and Herek 2013; Tee and Hegarty 2006). A meta-analysis by Whitley (2009) showed that among several forms of religiosity, religious fundamentalism was the strongest predictor of negative attitudes toward homosexual individuals. The result was confirmed in studies concerning prejudice toward transgendered persons (Nagoshi et al. 2018; Norton and Herek 2013).

We hypothesized that RWA, SDO, and RF would be related to a higher level of transphobia (Hypothesis 1). As in Study 1, we predicted that men would manifest a higher level of transphobia than women (Hypothesis 2). Apart from RF, we measured the level of self-assessed religiousness as the second dimension of religious attitude. This was because the relationship between religiousness and prejudice toward outgroups depends on how religious attitudes are conceptualized and measured (Whitley 2009).

Method

Participants

Similarly as in Study 1, participants in Study 2 were also Polish adults, aged 18–50 years-old (n = 300, M = 24.80, SD = 7.76) of whom 50% were women. They came from a different sample then the participants in Study 1. Sampling was by convenience: Undergraduate students from various universities in Warsaw and other adults participated in the study. Most of the participants had a high school (67.0%) or university education (30%), χ2(3) = 347.23, p < .001. The largest proportion (43.5%, n = 130) lived in a large city (over 500,000 residents), 13.0% (n = 39) lived in a medium-sized town, 23.4% (n = 70) in a small town (up to 50,000 residents), and 20.1% (n = 60) in the countryside, χ2(3) = 61.15, p < .001. In terms of religion, 77.7% (n = 233) of participants were Catholics, 1.0% (n = 3) were Buddhists, .3% (n = 1) were Protestants, .3% (n = 1) were Orthodox, 10.0% (n = 30) were atheists, 2.3% (n = 7) were agnostic, 4.3% (n = 13) declared “other,” and 4.0% (n = 12) declined to answer the question, χ2(7) = 1181.65, p < .001. A marginal amount of missing data was identified. One missing data point (of 9,599) was found for the GTS scale, and zero missing points were revealed for the TS scale. The levels of variance were calculated to find participants who did not pay attention while answering the questions.

Procedure and Measures

Participants were tested in small groups in classrooms or dormitories, or they individually filled out the paper-and-pencil questionnaires. All participants were given information about the aims and procedure, were assured that their responses would be anonymous, and were told they could refuse to participate or stop without giving any reason at any time. After giving their consent, they were administered questionnaires in counterbalanced order with demographic data presented at the end. An ethics approval was not required for our study as per applicable institutional guidelines and regulations, and the informed consent of the participants was implied through survey completion. Participants did not receive any financial or other compensation for participation in our study.

Transphobia

The GTS and TS were used to measure prejudice toward transgender individuals. Considering the results of the CFA conducted in Study 1, the two-factor solution for the GTS and the one-factor solution for the TS were used, showing good internal consistency for the genderism/transphobia (α = .89), gender bashing (α = .85), and transphobia scales (α = .89). The intercorrelations between the subscales were as follows: GTS–TG and GTS–GB (r = .57, p < .001), TS and GTS–GB (r = .44, p < .001), GTS–TG and TS (r = .89, p < .001).

Right-Wing Authoritarianism

The scale (RWA, Funke 2005) consists of three highly correlated subscales: authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism. There are 12 items in the scale (four for each subscale), each using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged and higher scores indicate greater right-wing authoritarianism. A sample item is: “The withdrawal from tradition will turn out to be a fatal fault one day.” The internal consistency of RWA in our study was marginally satisfactory (α = .68).

Social Dominance Orientation

The SDO scale (Duriez et al. 2005; Pratto et al. 1994) measures general individual difference orientation, expressing the value that people place on nonegalitarian and hierarchically structured relationships among social groups. The scale consists of 14 items, each using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged across items. Higher scores indicate a higher adherence to social-dominance orientation. A sample item is: “Some people are just more worthy than others.” The scale had good internal consistency in our study (α = .78).

Religious Fundamentalism

We used the RF Scale (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992; Polish version by Besta and Błażek 2007) to measure the extent of the belief that there is only one true collection of religious teachings, which include basic, natural, and infallible truths about humankind and God. Fundamentalists also believe in the existence of “forces of evil” that oppose this singular truth that should be fought and that only they have a special relation with God. The scale consists of 20 items using a 9-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged across items so that higher scores indicate greater religious fundamentalism. A sample item is: “God will punish most severely those who abandon his true religion.” The scale had good internal consistency in our study (α = .88).

Sociodemographic Variables

Participants reported demographic information including gender (male, female), age, education, size of the locality, and level of religiousness (1 – not believing at all; 5 – deeply believing).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The basic descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the study variables are presented in Table 4 (and separately for women and men in Table 2s of the online supplement). As shown in the correlation matrix, GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS were not related to sociodemographic indicators except for education and gender. Higher GTS–TG coexisted with lower educational levels, but the correlation coefficient was low. Men presented higher GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS levels. All three subscales coincided with higher RWA including its three subscales (Aggression, Submission, Conventionalism), higher SDO, and Fundamentalism. Also, GTS–GB and GTS–TG coexisted with higher levels of religiousness. Again, the correlation coefficients should be interpreted with caution because GTS–GB had a skewed distribution.

Regression Analyses

To check if GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS could be anticipated based not only on sociodemographic factors but also on the levels of factors that contribute to social conventionalism, we performed a hierarchical regression analysis. The data were prescreened for missing data, normality, and outlying cases as well as to check for fulfillment of assumptions (linearity, lack of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity). The only problematic measure was GTS–GB, which again had a positively skewed distribution. We decided to use log 10 transformation of GTS–GB.

According to the results, sociodemographic characteristics presented a nonsignificant (age, education) or significant but small role (size of locality only for GTS-TG) in evoking GTS–GB, GTS–TG, or TS, except for the role of gender (see Table 5). Men presented higher levels of GTS–GB (Mmen = 2.66, SDmen = 1.38, Mwomen = 1.93, SDwomen = .98, t(269.08) = 5.28, p < .001, d = .61), GTS–TG (Mmen = 4.68, SDmen = 1.24, Mwomen = 3.74, SDwomen = 1.21, t(289) = 6.65, p < .001, d = .77), and TS (Mmen = 5.08, SDmen = 1.31, Mwomen = 4.303, SDwomen = 1.37, t(289) = 5.07, p < .001, d = .59) in comparison to women. Higher declared religiousness was related to higher GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS after controlling for sociodemographic factors. As predicted, higher RWA and SDO significantly predicted higher levels of GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS. Higher fundamentalism was related to higher GTS–TG and TS but not GTS–GB. Authoritarianism was the strongest predictor of GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS among the included predictors. The final results (Block 3) were controlled for sociodemographic variables.

Discussion

Study 2 confirmed that RWA, SDO, and RF, as manifestations of rigid adherence to conventional social norms and preference for hierarchical social order, predict a higher level of transphobia. These results were consonant with those obtained in previous studies (Nagoshi et al. 2018; Makwana et al. 2018). However, one exception was revealed; in the third step of the regression analysis, there were no associations between religiousness or RF and the gender-bashing subscale of the GTS. This result indicates that although RF allows for the prediction of negative evaluation and emotional disgust toward transgender individuals, it is not automatically associated with readiness to use aggression against gender nonconformists.

This subtle result needs further exploration because previous studies have shown that religious fundamentalists exhibit a propensity to use and accept aggression in social relationships (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992). This propensity is due to a binary view of the social world in which religious fundamentalists stay on one side and act against people on the opposite side. However, what might play a role in the lack of associations among religiousness, RF, and GTS–GB is social desirability, which is a need for presenting oneself in a positive light. Previous studies have shown a positive association between the intensity of religiousness, religious fundamentalist beliefs, and social desirability (Chung and Monroe 2003; Genia 1996). Aggression is a socially undesirable behavior, whereas religious fundamentalists should be prone to present themselves as acting in a moral, altruistic, non-aggressive way. It is also possible that some aspects of RF might be related positively with a propensity to aggression toward gender nonconformists, whereas others might not. Vincent et al. (2011) showed that RF enhances antigay aggression to the extent that it promotes antigay prejudice. The authors claimed that RF might not support antigay aggression if high-RF individuals adhere more to religious views prohibiting aggression toward other humans than to whether these views are related to “good” and “evil” in the social world.

Controlling for all demographic variables, regression analyses revealed the hypothesized gender differences in all measures of the scales. In a third step, RWA, SDO, and RF did not change the pattern of results. However, it is worth noting that the obtained gender differences were not very large (rs from .21 to .27), and as in Study 1, the included predictors explained two (TS) and three (GT) times more variance than in GTS–GB.

Study 3

In Study 3, we considered three personological predictors of transphobia: (a) attitudes toward gender roles and beliefs about the (b) biological and (c) cultural origins of gender differences. The relation between attitudes toward gender roles and transphobia is well established (Costa and Davies 2012; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Tebbe and Moradi 2012), showing that the more one holds traditional attitudes about gender roles, the stronger the prejudice toward transgender persons. This seems logical because transgender individuals fail to fulfill “appropriateness,” meaning traditional gender roles that are ascribed to each gender. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 stated that the more traditional the attitudes toward gender roles, the higher the level of prejudice toward transgender persons.

Beliefs about the origins of gender differences (Studzińska and Wojciszke 2014) seem to remain in relation with attitudes toward gender roles. These two unidimensional scales reflect the degree to which one is convinced that differences between men and women are due to biological and cultural factors. The first one is a manifestation of essentialism according to which any distinction between the genders is a derivative of hidden, inevitable, biological traits that determine the nature of people who belong to one social category (DeLamater and Hyde 1998; Studzińska and Wojciszke 2014). The second one is a demonstration of social constructionism according to which people are convinced that gender differences stem from differences in gender socialization processes. Previous studies have shown that the higher the endorsement of beliefs about the biological origins of gender differences, the higher the level of sexism and legitimization of gender inequality, whereas the opposite was true for cultural beliefs (Studzińska and Wojciszke 2014). A study by Tee and Hegarty (2006) also evidenced that biological gender beliefs positively predicted opposition to trans persons’ civil rights. Considering “two sexes, two genders only,” the idea that only one possible classification of men and women to a gender category is characteristic for essentialists, whereas biological gender and psychological gender should be treated as more flexible and amenable to change by constructivists—with both types of convictions hypothesized to be inversely related to transphobia. Thus, we predicted that beliefs about the biological origins of gender differences would be positively related (Hypothesis 2), whereas beliefs about the cultural roots of differences between men and women would be negatively (Hypothesis 3) related, to transphobia.

The predictions related to gender differences in transphobia were the same as in Studies 1 and 2 (Hypothesis 4). We also made predictions related to sexual orientation of the participants. Based on the results of previous studies showing that heterosexual individuals manifested a significantly higher level of transphobia than did non-heterosexual respondents (Warriner et al. 2013; Willoughby et al. 2010), we hypothesized a similar pattern of results in Study 3 (Hypothesis 5). Finally, taking into account the results of Study 2, we also controlled for the self-identifying religiousness of participants when predicting transphobia based on attitudes toward gender roles and beliefs about the origins of gender differences.

Method

Participants

Another sample of 299 Polish participants were recruited for Study 3. The participants in Study 3 were undergraduate students from universities in Warsaw and other adults aged from 19 to 54, on average 22.50 years old (SD = 4.52) and of whom 71.9% (n = 215) were women. Women were overrepresented in the sample, χ2(1) = 57.40, p < .001. Of the participants, .7% (n = 2) had basic education, 67.8% (n = 202) had a high school education, and 31.5% (n = 94) had a university education, χ2(2) = 201.77, p < .001. Most of the participants (50.2%, n = 150) lived in a large city (over 500,000 residents), 13.4% (n = 40) in a medium-sized city, 15.1% (n = 45) in a small city/town, and the remaining 21.4% (n = 64) in the countryside, χ2(3) = 105.29, p < .001. Most of participants described themselves as exclusively heterosexual (n = 200, 70.2%), 3.2% (n = 9) described their orientation as exclusively being gay or lesbian. The remaining 26.6% chose a point on a continuum from the remaining range of 2 (heterosexual) to 8 (homosexual). The amount of missing data for the TS scale was minimal (three data points missing from 2,688 data points) and had a random character according to the Little’s MCAR test, χ2(15) = 21.93, p = .110. Also, the amount of missing data for the GTS scale was marginal (13 data points from 9,555 data points) and randomly distributed, χ2(244) = 231.29, p = .711. Thus, no data replacement or exclusion of participants was required. No particular attention checks were built into the procedure; however, the variance levels were monitored to identify participants with zero variance levels, thus potentially paying very little attention while answering the questions.

Procedure and Measures

We tested participants in small groups or individually. They were informed about the purpose, nature, and anonymity of the study and that they could refuse to participate or stop without giving any reason at any time. The paper-and-pencil questionnaires were filled out in counterbalanced order, with demographic data presented at the beginning of the booklet. An ethics approval was not required for our study per applicable institutional guidelines and regulations, and the informed consent of the participants was implied through survey completion. Participants did not receive any financial or other compensation for the participation.

Transphobia

The GTS and TS were used to measure prejudice toward transgender individuals. All scales showed good internal consistency reliability: genderism/transphobia (α = .94), gender bashing (α = .83), and transphobia (α = .90). As in Studies 1 and 2, the subscales were correlated with each other: GTS–GB and GTS–TG (r = .47, p < .001), GTS–GB and TS (r = .41, p < .001), GTS–TG and TS (r = .82, p < .001).

Attitudes to Gender Roles

The Attitudes to Gender Roles Scale (Roszak 2012) measures the way people perceive gender roles in society. The 18 items of the scale are based on societal values (as they should be) and societal practices (as they are). The statements used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). After recoding traditional items and averaging the scores, the higher scores denoted more egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles (α = .85). A sample item is: “The woman best realizes herself in life as a mother.”

Beliefs in Origins of Gender Differences

The scale (Studzińska and Wojciszke 2014) consists of 13 items belonging to two subscales: biological beliefs about the origins of gender differences subscale (e.g., “All the differences between men and women are caused by nature”; α = .77) and beliefs about cultural origins of gender differences subscale (e.g., “The differences between men and women are the result of upbringing”; α = .79). The statements used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged across items in the two subscales separately so that higher scores indicate stronger beliefs.

Sociodemographic Variables

Demographic information included gender (male, female), age, education (university, high school, vocational, primary), and size of the locality (city, medium-sized town, small town, countryside). Additionally, participants reported levels of religiousness and sexual orientation with the scale ranging from 1 (exclusively heterosexual) to 9 (exclusively homosexual) and two other possible answers, “asexual” and “I refuse to answer.”

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 6 (and separately for women and men in Table 3s of the online supplement). The sociodemographic features played a marginal role. Men presented significantly higher levels of GTS–GB (Mmen = 2.67, SDmen = 1.31, Mwomen = 2.20, SDwomen = 1.14, t(134.60) = 2.89, p = .005, d = .38), but not TS (Mmen = 4.18, SDmen = 1.50, Mwomen = 4.26, SDwomen = 1.46, t(297) = −.42, p = .672, d = .05) or GTS–TG (Mmen = 3.59, SDmen = 1.31, Mwomen = 3.76, SDwomen = 1.23, t(297) = −1.04, p = .299, d = .13). Higher levels of education and larger size of locality coincided with lower levels of GTS–TG. Higher age was related to lower TS and GTS–TG. All three subscales (GTS–GB, TS, GTS–TG) coincided significantly with stronger beliefs in biological sources of gender differences and weaker beliefs in cultural sources of gender differences as well as a more traditional approach to gender roles. Stronger religiousness went together with higher TS and GTS–TG. Sexual orientation (toward heterosexual) was significantly related to higher GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS. Because GTS–GB and sexual orientation had skewed distributions, the correlation coefficients should be interpreted in a careful manner.

Regression Analyses

We tested the significance of sociodemographic factors, religiousness, sexual orientation, biological and cultural sources of gender differences, and attitudes to gender roles as predictors of GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS by using a series of hierarchical regression models. The data were checked for violation of crucial assumptions. The only significant departures were those related to GTS–GB and the sexual orientation distribution. Both measures were positively skewed, so necessary transformation was applied. GTS–GB was square root transformed whereas the measure of sexual orientation was inverted.

Gender was a significant predictor of GTS–GB but not GTS–TG or TS (see Table 7). Men showed higher levels of GTS–GB in comparison to women. Age was negatively related to GTS–GB, GTS–TG, and TS. However, the coefficients were very small. Education did not play a role in GTS–GB, GTS–TG, or TS. The size of locality played a marginal role only with the relationship to GTS–TG; a larger-size locality was related to lower levels of GTS–TG. According to the final results (Block 3), after controlling for sociodemographic factors, higher declared religiousness, lower levels of sexual orientation (in the sense of being more heterosexual than homosexual), lower levels of beliefs in cultural sources of gender differences, more traditional attitudes toward gender roles, and higher beliefs in the biological sources of gender differences were significant predictors of higher GTS–TG and TS. However, beliefs in the biological sources of gender differences did not play a significant role in predicting GTS–GB. On the other hand, a similar pattern of the remaining variables significantly predicted GTS–GB. Lower sexual orientation values (more heterosexual), less strong beliefs in the cultural sources of gender differences, and more traditional attitudes toward gender roles were all significantly related to higher GTS–GB after controlling for sociodemographic variables.

Discussion

In Study 3, contrary to our previous studies, the only significant difference between men and women was obtained in the case of the GTS–GB subscale. Men expressed more readiness to use violence toward transgender individuals than women did but not to manifest more negative evaluation and disgust toward them. It is possible that this lack of gender differences in GTS–TG and TS was related to the prevalence of women in the studied sample (72%). However, this unequal gender sample structure did not influence GTS–GB, probably due to well-established gender differences in physical (and, to a lesser extent, verbal) aggression (Archer 2004), with men showing higher levels of aggressive behavior than women show.

The hypotheses related to gender role and beliefs in the origins of gender differences were confirmed, but only in GTS–TG and TS. When people believe more that the differences between the genders are biologically constructed, and when they acquire traditional gender roles, their evaluation and emotions toward transgender people are more negative. In contrast, together with beliefs that it is society that produces differences between men and women, the level of cognitive and emotional components of transphobia are diminished.

The role of beliefs about the origins of sex differences has rarely been investigated in the context of transphobia (e.g., Landén and Innala 2000). Beliefs about the determinants of transsexualism, however, were considered by Antoszewski et al. (2007). Their study revealed that people who believe that transsexualism has biological origins manifest lower prejudice toward trans people than do individuals who hold convictions about an environmental background of transsexualism. This pattern of results might be interpreted regarding a lower level of responsibility for one’s own gender invariance that was attributed to transsexual individuals by people who hold biological convictions about the etiology of transsexualism (Gerhardstein and Anderson 2010). Our study showed that essentialist thinking about gender differences (i.e., that men and women have a fundamentally different essence that manifests itself in the biological existence of only two genders; Hill 2006) favors transphobia. On the other hand, constructivist beliefs (i.e., that these gender differences are shaped by social and cultural norms, which allows for more free choice and self-identification in terms of gender; Hill 2006) are related to lower transphobia.

In the case of the GTS–GB subscale, only beliefs about the cultural origins of gender differences counted, as the regression analysis revealed. Participants’ readiness to aggression toward gender nonconformists was lower when they endorsed a more constructivist view of gender. However, both essentialist beliefs and traditional attitudes toward gender roles did not predict gender bashing. In our study, the included predictors explained only 4% of the variance of GTS–GB. Finally, according to Hypotheses 4 and 5, participants who self-identified as more religious and those who expressed heterosexual orientation were more prejudiced toward transgender people as measured by GTS–TG and TS. As in Study 2, religiousness did not influence GTS–GB, but the more flexible participants’ sexual orientation, the lower their level of readiness to aggress against trans people.

General Discussion

The results of three studies confirmed the utility of the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (GTS; Hill and Willoughby 2005) and the Transphobia Scale (TS; Nagoshi et al. 2008) in measuring attitudes toward transgender individuals in Poland. The results obtained through CFA in Study 1 confirmed the two-factor structure of the GTS (TG: Transphobia/Genderism and GB: Gender Bashing) and the one-factor structure of the TS. Both the GTS and the TS were characterized by high internal consistency. The obtained results confirmed the convergent validity of both measurements and showed theoretical similarities between the genderism/transphobia subscale of the GTS and TS.

As predicted, higher transphobia, as measured especially by the GTS–TG subscale and the overall TS, was positively related to prejudice toward sexual minorities, right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, religiousness, religious fundamentalism, and traditional attitudes toward gender roles. The positive role of these factors in transphobia was confirmed in previous studies in various cultural contexts (Costa and Davies 2012; Grigoropoulos and Kordoutis 2015; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Makwana et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2008; Norton and Herek 2013; Tebbe and Moradi 2012; Tebbe et al. 2014). All these predictors might be understood as a manifestation of the level of adherence to conventional social rules, which is the key factor of prejudice toward gender nonconformists (Nagoshi et al. 2008). We also found that beliefs about the biological origins of gender differences were positively related, and beliefs about the cultural origins of gender differences were negatively related, to transphobia. One might say that biological beliefs, as a manifestation of essentialist thinking about gender (Hill 2006), is a risk factor of prejudice toward transgender persons, whereas cultural beliefs, as an expression of constructivism (Hill 2006), act against prejudice toward transgender individuals.

However, it is worth noting that after controlling for demographic variables in the regression analyses, the β coefficients for most of the aforementioned predictors were not impressive. Values for religiousness, religious fundamentalism, social dominance orientation, and attitudes toward gender roles as predictors of transphobia oscillated around .20. This result might be interpreted in reference to the study of Adamczyk and Pitt (2009), who found that individual religiosity had more influence on attitudes toward sexual minorities in self-expressive than in survivalist cultures. The authors argued that in survivalist cultures, personal attitudes toward lesbian and gay people have support in cultural norms, so its effect is much smaller than in self-expressive cultures, which are more tolerant and liberal as opposed to the core statements of various religious norms.

Poland is a conservative country (Donaldson et al. 2017) oriented toward traditional values (Inglehart and Baker 2000), with a high position for the Catholic Church (Golebiowska 2017) and with one of the most restrictive laws related to LGBT people in Europe (ILGA 2019). This cultural and social context worsens attitudes toward individuals who do not conform to society’s gender expectations, as is shown in cross-national comparisons regarding attitudes toward LGBT individuals (Štulhofer and Rimac 2009; van den Akker et al. 2013). On the other hand, consistency between individual attitudes toward gender nonconformist and cultural norms denoting what is and is not appropriate in the context of gender reduces the influence of individual dispositions in shaping LGBT prejudice.

It is also worth noting that even in less conservative countries that are more egalitarian and have more favorable laws for LGBT people than Poland, prejudices toward transgender individuals are prevalent. For example, Dierckx et al. (2017) studied a large sample of Belgians and showed that in this country, which ranks at the top of the European countries in terms of LGBT individuals’ civil rights (Donaldson et al. 2017), a high level of anti-transgender prejudice might be observed. Similarly surprising were the results of a study Ngamake et al. (2013), who showed that in Thailand, known as a country open for those who want to medically change their gender and in which the transgender community is strong, overall attitudes toward transgender individuals were not different than those observed in a sample from the United States.

Although speculative, prejudices toward gender nonconformism seem to be a culturally universal phenomenon. It is shaped by individual and cultural norms (Donaldson et al. 2017; Inglehart and Baker 2000), but the influence of these norms might also have limitations. Recently it was shown that heterosexual men who endorsed egalitarian values held more positive attitudes toward gay men, but only when they were led to believe that there are biological differences between gay and heterosexual men (Falomir-Pichastor et al. 2015). When the biological similarity between two male groups was highlighted, egalitarianism had no effect on prejudice toward gay men.

Somewhat different were the results regarding the gender-bashing subscale of the GTS. Study 1 showed that only traditional but not modern homonegativity predicted readiness to aggress against transgender individuals. Study 2 revealed no relationship with religious fundamentalism. Finally, Study 3 showed a small and negative β coefficient in the case of cultural beliefs about the sources of gender differences and no relationship with biological beliefs about the origins of gender differences and attitudes toward gender roles. Moreover, the included predictors explained substantially less variance in GTS–GB than in GTS–TG and TS. It must be noted that the obtained results should be interpreted carefully due to a skewed distribution of GTS–GB in each study. However, this conceptual and statistical difference between cognitive and emotional (GTS–TG, TS) and behavioral (GTS–GB) components of transphobia suggests avoiding the general score of the GTS. The overall GTS score might blur the picture of the antecedents of transphobia and hence make it difficult to build intervention programs aimed at counteracting prejudice and aggression toward gender nonconformists.

As hypothesized, men presented significantly higher levels of GTS–TG, GTS–GB, and TS than women, confirming the result obtained in previous studies concerning not only transphobia (Costa and Davies 2012; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Nagoshi et al. 2008) but also homophobia (Nagoshi et al. 2008), attitudes toward gender roles (Mickelson et al. 2006), and sexism (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak 2014). In general, the results indicate that men more than women are socialized to maintain rigid differentiation between what seems to be “masculine” and “feminine.” Worthen (2013), when explaining gender differences in attitudes toward LGBT people, highlighted the role of heteronormativity—the assumption that only a heterosexual orientation is correct (Jackson 2006) —and of cisnormativity—the belief that only an accordance between biological and psychological genders is appropriate (Schilt and Westbrook 2009).

Many studies indicate that men are more prone than women to acquire such attitudes as a consequence of an antifemininity mandate (Falomir-Pichastor et al. 2010) and their precarious masculinity status (Vandello and Bosson 2013). Because manhood is a fragile social status, it can be easily lost or threatened, and men are motivated to prove their manhood by expressing typically masculine attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, men, but not women, following a gender threat manifest higher levels of aggression (Cohn et al. 2009), more traditional attitudes toward gender roles (Kosakowska-Berezecka et al. 2016), and stronger prejudice toward sexual minority (Konopka et al. 2019; Rivera and Dasgupta 2018) and transgender individuals (Konopka et al. 2019). All these attitudinal and behavioral manifestations allow one to present one’s self as typically masculine.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The general limitation of our study is that the participants might underreport some of the measured attitudes because of the broad public debate on LGBT rights and emancipation movement in Poland. It is a case of social desirability; some people want to be perceived as less prejudiced then they really are, especially when it comes to reporting behavioral (violence) and strongly emotional (hate) aspects of prejudice. This issue could be settled by conducting studies of more experimental nature and studies where social desirability variable is controlled.

Another limitation that should be addressed in further studies is the verification of the number of known transsexual individuals. As in Study 3, the result might be that the more gay and lesbian people one knows, the less transphobia is felt (Hill and Willoughby 2005; Tee and Hegarty 2006). Additionally, future research on the GTS and TS in the Polish context should include separate assessments of attitudes toward transgender men and women. It could be predicted that men would be assessed more negatively than women will be. Finally, we must note that both the GTS and TS are criticized for measuring not only attitudes toward transgender individuals but also overall attitudes toward gender nonconformity (Billard 2018). Thus, it seems reasonable to make a distinction between all gender-nonconformist groups to verify possible differences in attitudes toward individuals who belong to a particular group. Finally, although our studies confirmed the convergent validity of the GTS and TS, the discriminant validity of both instruments should also be verified in future studies.

Practice Implications

The results of our research could be useful for both theorists and practitioners. On one hand, our studies contribute to the field with two evidence-based and broadly used around-the-world measures for further use in Polish culture. On the other hand, practitioners such as therapists and policymakers could gain insights into the predictors of transphobia, which can be readily used to establish more suitable intervention programs, laws, or therapeutic techniques to improve the quality of life of this highly discriminated portion (at least 1%) of the Polish population. The GTS and TS are ready-to-use tools to measure attitudes toward transgender individuals in different social groups and to use in scientific research. This knowledge of attitudes could later be used as guidelines for introducing new laws by policymakers and for designing and implementing evidence-based interventions (such as the contact hypothesis or recategorization) by activists for given social groups to reduce discrimination.

Conclusions

The present studies provided us with two tools for measuring transphobia and insights concerning predictors of this type of prejudice. In Poland, a country with high levels of discrimination against gender nonconformists, it is a small step to measure and understand transphobia better and to do so by using reliable instruments with sound psychometric properties. Research conducted with objective scientific tools could be more convincing for the prejudiced part of society, which still constitutes the majority of Polish citizens.

References

Adamczyk, A., & Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: The role of religion and cultural context. Social Science Research, 38(2), 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.002.

Altemeyer, B., & Hunsberger, B. (1992). Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2(2), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0202_5.

Antosz, P. (2012). Równe traktowanie standardem dobrego rządzenia. Raport z badań sondażowych [Equal treatment as the standard of good governance – Report from survey research]. Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński.

Antoszewski, B., Kasielska, A., Jędrzejczak, M., & Kruk-Jeromin, J. (2007). Knowledge of and attitude toward transsexualism among college students. Sexuality and Disability, 25(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-006-9029-1.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8(4), 291–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291.