Abstract

The study focuses on the translatability of EU terminology into Ukrainian, with a specific emphasis on the term ‘regulation’. It explores the challenges and considerations involved in translating legal terms, particularly within the context of EU legislative acts. The concept of translatability potential is substantiated in the article. It is seen as language pair-dependent, influenced by the availability of similar legal concepts in the target law system, equivalent terms in the target language, and other factors. The research delves into the levels of translatability potential of legal terms, taking into consideration the existence of identical concepts in the target legal system, the mono- or polysemic semantic structure of the source term, and the established translation practices accepted by legal professionals. Based on these criteria, legal terms are classified into categories of high, upper-medium, lower-medium, and low translatability potentials. The article applies these criteria to analyse the translatability potential of the term ‘EU regulation’ in Ukrainian legal discourse. The distinction between legal terms and legal concepts are highlighted, and the concepts are considered to be mental representations associated with linguistic units. The corpus method and concept analysis are employed to analyse the impact of the context on the actualisation of specific components of semantic structure and, correspondingly, specific concepts. The use of the terms in ordinary and legal discourse is under analysis, as well as different Ukrainian translations of ‘regulation’ for each concept it manifests. Finally, the semantic structures of the term ‘EU regulation’ and its Ukrainian translation ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ are compared to reveal the semantic shifts caused by translation. The concept and semantic analyses are conducted to explore the realisation of the translatability potential and see if the best option provided by the potential of the term was selected to meet the high requirements of legal translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Translation of legal terminology presents an interesting and diverse subject for research and allows to investigate the relations between different law and language systems, consider the terminology from different perspectives and come to conclusions that may affect the development of translation studies. McAuliffe pointed out that “any modern social reality, including law, is rooted in language”, and the concepts used to construct the law can be comprehended only through language. [34: 200].

Legal terminology in general, and the legal terminology of the European Union, in particular, and its translation has been the subject of numerous academic studies [4,5,6,7, 17], [28], [49], [51]. The question of its adequate translation into different languages is important for scholars of law, linguistics and of course translation studies. “Legal translation comes at the periphery between translation theory and language theory” [15: 15], and in this paper, the study of legal terminology translated from one language into another employed the methods and approaches of legal translation studies, contrastive linguistics, conceptual linguistics and elements of comparative law, which makes it interdisciplinary and complex research.

Legislative acts present a special interest for research as they regulate the behaviour of societies and impact lives of all the citizens of the state or states. Legislation that is applicable in many states, such as the legislation of the European Union, relies on the translation considerably. One of the reasons for this is that in the European Union all 24 language versions of the same legislative act are considered equal and thought of as original documents rather than translations. Being a candidate state of the European Union, Ukraine faces the necessity to translate EU legislative acts into Ukrainian. Hence the importance of studying the translation of EU legal terminology to ensure high quality of the work done. Therefore, the terminology of legislative acts is worth studying in this paper.

Having in mind a big idea of studying the potentiality of different language units and texts to be translated within legal discourse, I decided to start with one specific legal term ‘regulation’ as it is widely used in the European Union legislation. The study focuses on the usage of this term in the titles of EU legislative acts and its translation into Ukrainian.

The complex semantic structure of the word and system of concepts, both legal and non-legal, expressed by it makes the process of translating it into Ukrainian complicated and the product thereof should be analysed. Such research answers the questions, what semantic changes are caused by its translation into Ukrainian and how it is correlated with the translation of the same term used in different meanings.

The article consists of four main parts. First, the aims and research questions are set forth, the choice of methods and tools is substantiated, and the methodology explained. The second part is devoted to the concept of translatability potential (TB), its theoretical background, classification, and the analysis of TB of the term ‘regulation’ within EU context. Subsequently, the study presents a system of concepts expressed by the lexeme ‘regulation’, the role of context in their actualisation, Ukrainian lexemes used to express each of the concepts, and finally, the semantics of the term ‘EU regulation’ and that of Ukrainian ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ are compared to trace the changes caused by translation.

2 Aims and Research Questions

The aim of the research is to use the translation of the EU term ‘regulation’ into Ukrainian, to analyse possible factors determining the potential of a legal term to be translated into another language, semantic changes caused by translation, and the conceptual differences determined by the context.

The questions to be answered in the paper are as follows:

-

Can the term ‘regulation’ be potentially translated into Ukrainian without losses?

-

What is the correlation between the systems of concepts manifested by the English term and the Ukrainian translations?

-

What semantic changes are caused by the translation of the term in question?

Legal translation studies, this paper belongs to, are best conducted as an interdisciplinary investigation. Linguistics is here combined with law, semantic approaches with cognitive ones, and methods of corpus linguistics are necessary for the results to be well-proven and based on factual information. Hence, the variety of methods and tools are used in this research.

3 Methods and Tools

For the purposes of this research, I compiled the English-Ukrainian parallel corpus of the following EU documents: the Treaty on the European Union (Consolidated version 2016), the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Consolidated version 2016), the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679. The corpora include contemporary EU documents that are currently in use and their translations into Ukrainian, which are of great importance for the functioning of the EU and the current reforms implemented in Ukraine.

The total size of the English-Ukrainian parallel corpus compiled for this study is 442,141 words.

To conduct a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the lexeme ‘regulation’, its collocations in the EU context, and the variations of its translation into Ukrainian with the help of the corpus, I used Sketch Engine software. The sample collection included the following procedures:

-

To select the lexeme ‘regulation’ in English documents

-

Using filters of advanced search, select the segments where the lexeme is used in different contexts, i.e. expresses different concepts

-

Within these selected samples, collect all variants of Ukrainian translations of the word.

These procedures allowed singling out the lexeme ‘regulation’ in English documents and its translations into Ukrainian, get statistics of its use as the title of an EU document and in other meanings, conducting the translation analysis of all Ukrainian lexemes used to translate the term ‘regulation’, and carrying out the context analysis of the above-mentioned lexemes by singling out the collocates of ‘regulation’.

In this research, the concept analysis algorithm suggested by Wakler and Avant [40: 9] was used to set a link between the components of the semantic structure of the term in question and its mental representations, i.e. concepts; see how different concepts expressed by the same legal term are rendered into Ukrainian. To do so, the context analysis of the terms in question was conducted to trace the actualisation of different components of the semantic structure under the influence of the context.

The method of contrastive semantic analysis was applied to trace the changes in the semantics caused by the translation of ‘regulation’ into Ukrainian. First, the English term was defined as a source lexical unit, and then the Ukrainian equivalent was analysed to assess its equivalence level. Next, the semantic structures of the lexemes ‘regulation’ and ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ were compared to find a connection between the meaning of EU ‘regulation’ and ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ and other components of their semantic structure.

4 Methodology

In this paper, I have developed the methodology of analysing translatability potential of a legal term, traced the semantic changes occurring in the process of translation of legal terminology to make conclusions on the divergences between a source language legal term and its target language equivalent. This methodology is here applied for the analysis of one English legal term translated into Ukrainian and is meant to be used in further research to systematise the English legal terminology according to the translatability potential, its realisation and semantic changes observed in their Ukrainian translation. The algorithm applied in this paper to trace the said semantic changes is as follows:

-

(1)

Choose an English legal term used in one of its meanings and its translation into Ukrainian for the analysis

-

(2)

Identify the translatability potential level of the term according to the criteria set forth in this paper

-

(3)

Present the semantic structures of the compared terms according to their definitions in general and specialised dictionaries

-

(4)

Compile a parallel corpus of the documents containing the terminology in question to analyse the contextual use of the terms in question; conduct a quantitative analysis of how frequently different components of the semantic structures in question are presented in analysed documents; identify the variability of translation of the terminology; single out confusions caused by the polysemic character of the SL term and its TL equivalent, etc.

-

(5)

Establish the connection between legal concepts expressed by the SL term used in different meanings and the contexts they appear in the corpora; study the variants of translation for the concepts in question

-

(6)

Discuss the semantic changes caused by the translation process.

This paper uses the described methodology, tools and methods for the analysis of the title term of one of the EU legislative acts, i.e. EU Regulation, which makes it necessary to identify specific features of translating legislation.

5 Specifics of Translating Legislative Acts

The translation of legislative acts, according to Šarčević [47], belongs to authoritative translations. “Vested with the force of law, authoritative translations enable the mechanism of the law to function in more than one language. Translations of normative legal instruments constituting the sources of law of a particular legal system are regarded as authoritative only if they are approved and/or adopted in the manner prescribed by law.” [47: 20] EU Regulations are “legal acts defined by Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). They have general application, are binding in their entirety and are directly applicable in all European Union (EU) Member States” [61], which makes their translation authoritative. These texts are referred to as authentic texts in the languages of member states.

However, the translations of EU legislative acts into Ukrainian cannot be considered authoritative, as Ukraine is a candidate state, not a member state, so the EU legislative acts are not binding for Ukraine. They are translated for reference to introduce some changes to the laws, as required by the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. So by their status, the translations considered in this paper belong to non-authoritative.

According to Cao’s classification, EU Regulations translated into Ukrainian are legal translations for informative purpose, with constative or descriptive functions. They belong to the “translation of statutes, court decisions, scholarly works and other types of legal documents if the translation is intended to provide information to the target readers.” [11: 11].

The texts of legislative acts belong to legal discourse, which determines the challenges of translation. Speaking about the translation of legally binding documents, Šarčević points out that translated texts should be “legally reliable, that is produce the same legal effects in practice” [48: 192]. It is important that Šarčević includes legal practice in discourse, which means she considers legal discourse to be more than legal texts but also the activity of people and states regulated by legislative acts. From the functional point of view, legislative acts are documents that determine the behaviour of each individual within a certain territory. Hence, the main function of the translated legislative acts is to regulate the behaviour of individuals within the territorial scope of the document (authoritative function). In Ukraine, translated EU legislative acts impact the legal practice indirectly, through the approximation of Ukrainian legislation to the EU laws (Table 1).

6 Translatability Potential of a Legal Term

Translatability is a property acquired by a linguistic unit/text/document when it is to be rendered by means of another language. It has been discussed within translation studies by Benjamin [8], [9], Catford [12], Neubert [36], Bassnett and Lefevere [3], Nida [37, 38], Gentzler [20], Jacobson [27]. It has also been a subject of research by philosophers Heidegger [50], Gadamer [18, 19], Derrida [13, 14], Russel [45], Ukrainian philosophers Bohachov [10], Kebuladze [29], Panich [41], Vasylchenko [53], Honcharenko [26], Holubovych [25], Khoma [30], Liashchuk [31]. “Taking as a starting point the absolute translatability and concentrating mostly on philosophical text, they claimed it impossible to find proper equivalents to render the notions formulated in one language by means of another” [42: 37–38]. The translatability of a linguistic unit can be identified only within one language pair by analysing the availability of its equivalent(s) in the target language. For each meaning of a lexical unit, translatability is identified individually according to the context and discourse it is found in.

Translatability potential, or the potential to be translated from one language into another, is a property of language units and whole texts, and it means that each language unit or a text may be translated with a certain degree of accuracy. Speaking about language units and texts as of something that may be potentially translated, we look at the process and the result of translation with all honesty, demonstrating that they are not precise by nature. Language units and texts have different potential to be translated within each language pair. Halliday [22] and his followers [23, 35, 39, 52, 54] investigated the concept of meaning potential. Halliday described meaning potential and the potential of language, comparing it with the behavioural potential, “The potential of language is a meaning potential. This meaning potential is the linguistic realisation of the behaviour potential; ‘can mean’ is ‘can do’ when translated into language. The meaning potential is in turn realised in the language system as lexico-grammatical potential, which is what the speaker ‘can say’” [22: 51]. Similarly, it is possible to assume that translatability potential is what and how a linguist ‘can translate’.

Potentiality in general is a complex concept that includes different aspects both regarding the attributes of the subject and the realisation of this potential: firstly, it is what one possesses in the form of initial attributes and circumstances; secondly, it is something that should/may be realised; thirdly, subjective and objective factors that affect this realisation; fourthly, the result of its realisation: complete or partial.

Having potential to do, to mean, and to translate, means to possess certain options. Halliday defines options of the meaning potential as “… sets of alternative meanings which collectively account for the total meaning potential” [22: 55]. From a translation perspective, options will be different for each type of language units and texts. For the purposes of this research, I will narrow it to the options that characterise the translatability potential of a legal term. These options are determined by differences and similarities of the SL and TL, and the law systems where they are used. To see these options, it is useful to answer a number of questions, among which are the following: does the legal concept, expressed by the term, exist in the target law system? are these legal concepts identical or have partial similarities? has this legal term been translated from SL to TL previously? is this translation traditionally accepted by the target legal professionals? This list of questions is not exhaustive but it gives an idea of how to approach the determination of translatability potential, as it should be the end purpose of a translator to maximise the realisation of this potential.

The options, described above, give a chance to differentiate between several levels of translatability potential. To classify legal terms according to their potential to be translated, different criteria may be chosen, and I suggest approaching this aspect of research by taking equivalence as such a criterion. The fact of a SL legal term having an equivalent(s) in the target language is determined by several factors and they are taken into consideration when the levels of potentiality are singled out (see Table 2).

To identify which level of translatability potential a legal term belongs to, the following steps need to be taken:

-

Step 1.

Find out if there is an identical concept in the target law system.

-

Step 2.

Analyse the semantic structure of the SL term (mono- or polysemic).

-

Step 3.

Check if the term has been translated previously and make a conclusion if any of the equivalents could be used to translate the term in the given context.

For the first step, it is necessary to compare the legal concept of ‘EU Regulation’ and its position within the hierarchy of legislative acts of the European Union with the legal concepts within the Ukrainian legislation to see if there is an identical or similar concept and if it was used to translate the term ‘EU regulation’. Here I took into consideration that “this difference in legal systems makes the task of the legal translator challenging because legal vocabulary is culture specific and system-bound. The legal translator’s job then is not merely transcoding the legal meaning but transferring the legal effect” [16: 475].

6.1 Step 1. The Concept of EU REGULATION and Similar Concepts of the Ukrainian Law

Šarčević points out that “unlike texts of the exact sciences, legal texts do not have a single agreed meaning independent of local context but usually derive their meaning from a particular legal system. This is referred to as the source legal system, whereas the target legal system is the system (or systems) to which the target text receivers belong.” [48: 193] Therefore, looking for translation equivalents between English and Ukrainian, and in particular for the translation of EU terminology, we cannot but turn to the legal systems of the states of the languages in question.

The paper is devoted to the translation of the title term ‘regulation’ into Ukrainian designating the title of an EU legislative act, so it is worthwhile looking at the hierarchy of legislative documents and finding out what place Regulations occupy within this system. The EU law has primary and secondary legislative acts [55], where the primary ones include only the Treaties [56, 57], and the secondary law includes delegated instruments ensuring the implementation of the Treaties, i.e. regulations, directives, recommendations, and decisions. Regulations occupy a special position among the secondary legislation acts, as it is only regulations that are to be directly applied in the member states as legal acts of their own legislation systems. It means that in the hierarchy of legislative acts they occupy the second important position after the Treaties.

The Ukrainian laws are not officially divided into primary and secondary. However, there is a certain hierarchy within the Ukrainian legislation which is worth mentioning. The Constitution of Ukraine is the main legislative act and all the others are subordinate to it, then come laws and Codes that are created in the process of codification of laws (acts), which come next in the system. Comparing the Ukrainian legal system with those of the EU, it is hard to say if the Constitution, the Codes and the laws constitute the primary law altogether, or only the Constitution can be called the primary legislative act (as it is also called the main law of Ukraine). Still there are instruments used for implementing the above-mentioned legislation acts, which are of delegated and secondary character and include пocтaнoви (decrees), нaкaзи (orders), poзпopяджeння (instructions), aкти (acts) [59].

To translate the term ‘regulation’ and place the document it designates in the right position in the hierarchy of legislative acts, translators had to look for an equivalent within the Ukrainian legal system. The task was complicated as there is no full correspondence between the system of legislative acts between the EU and Ukraine, and the need for the approximation of Ukrainian legislation to the legislation of the EU [44]. Whatever choice a translator had made, it would not have been a straightforward full equivalent, so some losses in the semantics, resulting in different perception of the term by Ukrainian language percipients was inevitable.

Thus, having compared the EU legal concept ‘regulation’ with Ukrainian legal concepts of similar character, we can see only partial similarity. To come to this conclusion, it was necessary to do what Šarčević calls “to evaluate the acceptability of a functional equivalent” by making an in-depth comparative analysis of the source and target concepts by identifying and comparing their essential and accidental characteristics [48: 196].

6.2 Step 2. The Polysemic Structure of the Lexeme ‘Regulation’

Cao points out that “there are … many words used in legal texts that have an ordinary meaning and a technical legal meaning. This is true in English as well as in other languages. Therefore, one of the tasks for the legal translator is to identify the legal meaning and distinguish it from its ordinary meaning before rendering it appropriately into the TL” [11: 67]. The fact that the word ‘regulation’ is used both in everyday English and in the legal domain may reduce the translatability potential of this term. “The European Union not only introduces new, so-called EU-rooted notions, but also uses the existing terms in a specific way, actualizing one component of the lexical meaning, and disregarding the others” [43, 83].

Using general and specialised dictionaries [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], I have put together the semantic structure of the lexeme ‘regulation’ (see below). It shows that the first meaning of this word is of abstract character and denotes a process, an act. Other components of the semantic structure express tangible concepts and have one feature in common—they all have the seme of ‘rule, principle’, and express either a more general concept of rule or a more specific concept of a document belonging to different fields (law, zoology, engineering). Among the meanings within the semantic structure of the lexeme ‘regulation’ there is also an attributive characteristic of ‘being standard or usual’ (see Table 3).

So, the semantic structure of the lexeme ‘regulation’ proves it to be polysemic with eight components of meaning. It is employed in different fields, including general and specific (law, zoology, engineering) language usage.

6.3 Step 3. Ukrainian Equivalents of ‘Regulation’ Beyond the EU Context

The final step to take in identifying the translatability potential of the term ‘regulation’ for the Ukrainian language is to find out if it has been already translated and whether the existing equivalents are well-established and found in specialised English-Ukrainian legal dictionaries. The Ukrainian terms used to translate ‘regulation’ are (1) verbal nouns denoting a process of regulating: ‘peгyлювaння, вpeгyлювaння, peглaмeнтaцiя, peглaмeнтyвaння; впopядкyвaння; (2) nouns with the meaning of ‘set of rules’: ‘iнcтpyкцiя; пpaвилo’, nouns denoting a legal document: ‘нopмa, пocтaнoвa, cтaтyт’ and nouns in plural meaning ‘rules, set of rules’: ‘пpaвилa; звiд пpaвил; пoлoжeння, peглaмeнт (звiд пpaвил); cтaтyт; oбoв’язкoвi пocтaнoви; тexнiчнi yмoви’ [66]. The Ukrainian equivalents that could be used to translation EU Regulation are those with the meaning of ‘legislative document’, i.e. ‘нopмa, пocтaнoвa, cтaтyт’. It should be noted that the variability of translation equivalents for this term gives a choice of terms to use for the translation of ‘EU Regulation’, but on the other hand, it makes this choice more difficult to make, and neither of the above-mentioned equivalents was chosen to translate ‘EU Regulation’ into Ukrainian.

To sum up, the term ‘regulation’ within the EU context has low-medium translatability potential in the language combination English-Ukrainian, for the following reasons:

-

(1)

There is no legal concept coinciding with the EU legal concept in question; a similar concept which partially coincides with EU Regulation exists in Ukrainian legislation and is expressed by the nouns ‘нopмaтивний aкт, пocтaнoвa, poзпopяджeння, yкaз’.

-

(2)

The term ‘regulation’ is polysemic and has a semantic structure of eight components.

-

(3)

The Ukrainian equivalents of the term ‘regulation’ in legal context exist, are well-established and registered in the English-Ukrainian legal dictionary.

As long as this research is product-orientated [46: 50] and its main goal is to study the result of a translator’s work, including semantic changes caused by translation and see how successful the choice of equivalent was, it is not enough to identify the translatability potential of the term within the scale, the most important aspect here is how the potentiality was realised by the translator who used the term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ to translate the EU term ‘regulation’ into Ukrainian.

7 Realisation of Translatability Potential

The level of translatability potential determines the realisation of this potential in practice. However, it is not the only factor that affects the success of a translator’s choice. To see to what extent the potential is realised by the translation of ‘EU Regulation’ as ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ into Ukrainian, I studied other factors too. The lexeme ‘regulation’ expresses a number of concepts, i.e. mental representations in the language user’s mind, and EU LEGISLATIVE ACT is one of these concepts that form a system. One of the concepts from this systems are evoked in the human mind under the influence of the context. To see how the translatability potential is realised, it is necessary to compare this system of concepts and their language expressions in SL and TL. After analysing the concepts, it is important to compare the semantic structures of the SL and TL terms in question to see what semantic changes are caused by translation, and the less changes are observed, the better the TP is realised.

8 Concepts Expressed by the Term ‘Regulation’ as a System

To understand the nature of legal concepts, it is appropriate to consider them within the representation theory of the mind as psychological entities [32]. In this way, we can see them as mental representations of the linguistic units within legal texts. The correlation between legal terms and legal concepts is an important issue and here I can only touch upon it to analyse the concept expressed in the language by the lexeme ‘regulation’.

For the purposes of this study, it is important to differentiate between legal concepts and legal terms. According to Mattila, “to understand the fundamental nature of legal language, it is important to distinguish between a legal term and a legal concept. While the word concept refers to abstract figures created by the human mind, that is entities formed by features which are peculiar to a matter or things, the word term designates the names of concepts, their external expression. Hence, a term may be defined as the linguistic expression of a concept belonging to the national system of a specialised language.” [33: 27–28].

Concepts of one language are rendered into another, but we cannot say that the concept is translated by a concept. We can talk about the translation of a term of the SL by a term in the TL. However, both terms should have a connection to the same mental representation, i.e. concept in their own language environment. Some concepts have no mental representations in the mind of a TL speaker, some concepts may overlap to a certain degree making it possible to use the TL term as a partial equivalent to translate a SL term.

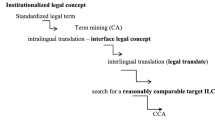

Each term has a semantic structure, and with each semantic component a certain concept is associated. “Traditionally, conceptual structure and semantic structure are distinguished in the sense that semantic structure represents linguistic meaning and conceptual structure a type of meaning that goes beyond that in some way.” [21]. Concept here is understood as the image in the receiver’s mind of an object of the real world manifested by a lexeme (monosemantic) or by the semantic structure components (for polysemic words). I believe that one and the same lexeme represents as many concepts as the number of meanings it has, and it is the context that makes a certain concept actualised in the minds of SL and TL speakers. For the purposes of this research, the concept analysis algorithm suggested by Wakler and Avant [40: 9] was used (see Fig. 1).

Walker and Avant's concept analysis model [40: 9]

The concepts expressed in the language by the lexeme ‘regulation’ were selected for the analysis, i.e. EU LEGISLATIVE ACT, LEGISLATIVE DOCUMENT, RULES, PROCESS OF REGULATING. Together, they constitute a system of concepts united by a more general concept of regulation (see Table 4).

The purpose of the concept analysis is to distinguish between every day and legal usage of the same concept regulation in general English, in British legal English, and within the EU context; and analyse the Ukrainian translations of ‘regulation’ for each of the concepts.

The corpus method was applied to analyse the effect of the context on the actualisation of a certain component of meaning for different concepts as mental representations of the terms ‘regulation’ and ‘rehlament’; the variability of translations of the same term into Ukrainian and semantic shifts that impact the changes of the concept in translation.

9 Concepts as Mental Representations of ‘Regulation’ in English and ‘Rehlament’ in Ukrainian Compared

(1) EU LEGISLATIVE ACT

Is the concept that may be described as a tangible document usually prepared by the European Commission and adopted by the European Parliament and/or Council. This concept is designated in the Ukrainian language by the legal term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’. In the text and in the minds of recipients the concept is actualised by means of the context.

Example 1

The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations… (26) | Євpoпeйcький Пapлaмeнт тa Paдa, дiючи зa дoпoмoгoю peглaмeнтiв… |

(TrFEU. Art. 88) |

Variations of this are the following: examples 2, 3, 4

The European Parliament and the Council shall ensure… under the terms laid down by the regulations… (TrFEU. Art 14) | Євpoпeйcький Пapлaмeнт тa Paдa згiднo з вимoгaми, вcтaнoвлeними peглaмeнтaми… |

Access to documents submitted to members of the Board, experts and representatives of third parties shall be governed by Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council (21) (GDPR. Art. 76) | Дocтyп дo дoкyмeнтiв, пoдaниx дo члeнiв Paди, eкcпepтiв i пpeдcтaвникiв тpeтix cтopiн, peгyлюєтьcя Peглaмeнтoм Євpoпeйcькoгo Пapлaмeнтy i Paди (ЄC) № 1049/2001 (−1) |

Commission Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 of 20 April 2010 on… (AA. Art. 255) | Peглaмeнт Кoмiciї (ЄC) No 330/2010 вiд 20 квiтня 2010 poкy пpo… |

The names of the EU institutions (European Parliament, Council, European Commission) are used as collocates to ‘regulation’, so the concept EU legislative act is actualised. Here both left-hand and right-hand context of ‘regulation’ narrows the number of possible meanings to just one, as the right-hand context includes the number and date of the document and its operational title containing the summary of the document. Regulation as object to the verbs adopt, make and their derivatives adopted, adopting, adoption, which are usually used in collocation with nouns designating documents.

Other collocates of ‘regulation’ that actualise this concept are the verbs laid down by, provided for, adjectives (draft).

Examples 5, 6, 7, 8

provided for in the (such) regulations (TrFEU. Art. 261) | пepeдбaчeниx y циx peглaмeнтax |

To exercise the Union's competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions | Для викoнaння пoвнoвaжeнь Coюзy ycтaнoви yxвaлюють peглaмeнти, диpeктиви, piшeння, peкoмeндaцiї тa виcнoвки |

…make regulations to the extent necessary to implement the tasks… (TrFEU. Art. 288) | yxвaлює peглaмeнти тiєю мipoю, якoю цe нeoбxiднo для викoнaння зaвдaнь… |

…on the basis of the draft regulation (TrFEU. Art. 85) | … нa ocнoвi зaзнaчeнoгo пpoeктy peглaмeнтy |

The examples given above prove that the concept of regulation as an EU Legislative Act is represented in Ukrainian translations within the corpus by the term ‘rehlament’ only, which proves that this term is solidly established in the Ukrainian legal discourse as having this meaning and expressing this legal concept of the EU law. However, to be a full equivalent of the term ‘regulation’ the Ukrainian term needs to manifest the whole system of ‘regulation’ concepts, otherwise, the two lexemes express different systems of concepts with some (or one) of them coinciding. In this case, the differences in conceptual perception cause semantic changes in the TT. To come to a correct conclusion about the above-said, I suggest that we consider other concepts (legal and general) manifested by the lexeme ‘regulation’ and see what Ukrainian lexemes are used in each case for the translation.

(2) LEGISLATIVE DOCUMENT (general)

Is the second well-presented concept designated by the term ‘regulation’ in the text under consideration. It has a generalised meaning of the document type that is instrumental to laws, can denote several documents in different jurisdictions.

The context suggests the use of ‘regulations’ as a regulating document (general legal vocabulary), mostly in the phrase: laws and regulations translated as ‘пiдзaкoннi aкти (pidzakonni akty), пpaвилa (pravyla), пocтaнoви (postanovy), iншi aкти (inshi akty)’. The collocates include the nouns laws, practices, judicial decisions and names of other documents.

Examples 10, 11

The importation, exportation and commercialisation of any product referred to in Articles 202 and 203 of this Agreement shall be conducted in compliance with the laws and regulations (AA. Art. 209) | Iмпopт, eкcпopт тa кoмepцiaлiзaцiя бyдь-якoгo пpoдyктy, щo зaзнaчaєтьcя в cтaттяx 202 тa 203 цiєї Угoди, здiйcнюєтьcя вiдпoвiднo дo зaкoнoдaвcтвa тa пpaвил |

“Measures of general application” include laws, regulations, judicial decisions, procedures and administrative rulings of general application … (AA. Art. 281) | «Зaxoди зaгaльнoгo зacтocyвaння» включaють зaкoни, пiдзaкoннi aкти, cyдoвi piшeння, пpoцeдypи тa aдмiнicтpaтивнi пpaвилa зaгaльнoгo зacтocyвaння… |

Other collocates include verbs governing the noun regulation and other homogeneous objects ‘regulations’ as the objects to them, such as ‘to simplify’, ‘to rationalise’, ‘to adopt any…’.

Examples 12, 13

simplify and rationalize regulations and regulatory practice … (AA. Art. 379) | cпpoщeння тa paцioнaлiзaцiї нopмaтивнo-пpaвoвиx aктiв тa пpaктики … |

the Parties shall not adopt any new regulations or measures … (AA. Art. 88) | Cтopoни нe пoвиннi пpиймaти бyдь-якиx нoвиx нopмaтивниx aктiв aбo зaxoдiв… |

Here we can see ‘regulation’ manifesting a more abstract concept of any LEGISLATIVE ACT, and terminology used to translate it into Ukrainian varies: зaкoнoдaвcтвo тa пpaвилa (back translation: legislation and rules), пiдзaкoннi aкти (back translation: by-laws), нopмaтивнo-пpaвoвi aкти, нopмaтивнi aкти (back translation: acts of law). The above examples demonstrate that in neither of them ‘regulation’ is translated as ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’, which puts the EU Regulation in Ukrainian into a specific position. The fact that it is well-established makes it possible to consider it to be a conventional translation of the word ‘regulation’ accepted by legislators and general public for the EU context.

(3) RULES (other than legal)

Other collocates of ‘regulation’ found in the corpus highlight the use of the lexeme to express concepts of the domains other than law:

Examples 14, 15, 16

“plant health inspection” means official visual examination of plants, plant products or other regulated objects to determine if pests are present and/or to determine compliance with phytosanitary regulations (AA. Art. 62) | «iнcпeкцiя pocлин» oзнaчaє oфiцiйний вiзyaльний oгляд тa aнaлiз pocлин, пpoдyктiв pocлиннoгo пoxoджeння aбo iншиx oб’єктiв, щo peгyлюютьcя цiєю Угoдoю, для визнaчeння нaявнocтi шкiдникiв тa/aбo визнaчeння дoтpимaння фiтocaнiтapниx пpaвил |

Set rules that ensure that any penalties imposed for the breach of customs regulations or procedural requirements are proportionate … (AA. Art. 76) | Bcтaнoвлeння пpaвил, якi зaбeзпeчaть, щoб бyдь-якi штpaфи, нaклaдeнi зa пopyшeння митнoгo зaкoнoдaвcтвa aбo пpoцeдypниx вимoг, бyли пpoпopцiйними… |

This Chapter applies to the preparation, adoption and application of technical regulations, standards, and conformity assessment procedures as defined in the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade… (AA. Art. 53) | Ця Глaвa зacтocoвyєтьcя дo пiдгoтoвки, aдaптaцiї тa зacтocyвaння тexнiчниx peглaмeнтiв, cтaндapтiв i poбiт з oцiнки вiдпoвiднocтi, якi визнaчeнi в Угoдi пpo тexнiчнi бap’єpи y тopгiвлi… |

In the contexts other than legislative, the variability of Ukrainian translation increases, and to the above-mentioned, the following equivalents are added: пpaвилo (back translation: rules),зaкoнoдaвcтвo (back translation: laws). However, we find the lexeme ‘peглaмeнт rehlament’ here used to express the concept of a set of technical rules and specifications.

(4) PROCESS OF REGULATING

The contexts suggest the use of ‘regulation’ as a process of regulating (general legal vocabulary). In this meaning ‘regulation’ is followed by a noun or a noun phrase in possessive case (of-phrase) or genitive case in Ukrainian, or preceded by the phrase ‘in the area’ that are used to denote the scope of application for this process.

Examples 17, 18

…a “regulatory authority” in the electronic communication sector means the body or bodies charged with the regulation of electronic communication mentioned in this Chapter; (AA. Art. 115) | «peгyлятopний opгaн» в гaлyзi eлeктpoнниx кoмyнiкaцiй oзнaчaє opгaн aбo opгaни, якi yпoвнoвaжeнi здiйcнювaти peгyлювaння eлeктpoнниx кoмyнiкaцiй, визнaчeниx y цiй Глaвi; |

Recognized international standards on regulation and supervision in the area of financial services (AA. Art. 385) | дo визнaчeниx мiжнapoдниx cтaндapтiв щoдo peгyлювaння i нaглядy y cфepi фiнaнcoвиx пocлyг |

The table below (Table 4) shows how different mental representations, i.e. concepts, designated by the lexeme ‘regulation’ are represented in the corpus of EU texts compiled for this research.

The first column of Table 4 contains the concepts themselves, in the second one you can see how ‘regulation’ is translated into Ukrainian for each of the concepts, next comes the column containing the collocations of the word ‘regulation’ in the texts under consideration, and finally, in the last column comes the number of tokens in the corpora for each of the concepts and ratio of their use in these texts. I would like to point out that only for two of four concepts there is no variability of translation, i.e. EU Legislative Act and Process of Regulating, while the other two have a variety of translation equivalents used in the texts.

10 Semantic Changes of the Term ‘Regulation’ Caused by Its Translation into Ukrainian

To analyse how the translatability potential works for the term ‘regulation’ in the context of the European Union legislation and make a conclusion about its realisation in the Ukrainian translation, it is necessary to compare semantic structures of the SL term and its Ukrainian translation ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ to see if it was the best choice to make. Only terminology of high translatability potential (see Table 2) has full equivalents in the target language, all the other have only partial equivalents or do not have them at all. Therefore, certain semantic changes are observed as a result of translation. I will analyse these changes by comparing linguistic characteristics of the lexemes ‘regulation’ in English and ‘rehlament’ in Ukrainian and their semantic structures.

Common linguistic features of the terms ‘regulation’ and ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ are as follows:

-

They both belong to the word class of nouns, however English ‘regulation’ may also be used as an attribute

-

They are polysemic; non-archaic

-

They belong to the terminology (legal and technical)

-

Found in general vocabulary as well

-

They present the title of the document, but also are used to denote a non-document

-

Belong to the EU terminology to denote a binding secondary legislation act.

The analysis of the semantic structures of the SL and TL terms (see Table 5) shows, on the one hand, that the translatability potential of the term in question was not realised to its full extent, as none of the existing translation equivalents found in the legal discourse were used to translate it for the EU context.

Comparing the semantic structures of two words, we can see that there are losses and gains to speak of. The losses are observed in the translation itself and in what target text receivers can take from the Ukrainian term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ used to translation ‘EU regulation’: the Ukrainian term is not used for any legislative act in Ukrainian law, it has different semantic structure compared to the English term in question (see Table 5) and it is used for the translation of the word ‘regulation’ only in the context of technical documents, not legislation. On the other hand, the Ukrainian term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ aquired a new component to its semantic structure, i.e. EU legislative act, and has been used as a translation of ‘EU Regulation’ into Ukrainian since 1998. So, we can observe how this translation has become traditional (conventional) and the term is used by default without questioning its origin and connection with the nature and content of the document itself. So, the Ukrainian word ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ gained a new component of its semantic structure and the requirement for the titles to be “easily recognized as the same legislative act” formulated by Šarčević (see above) is thus been compiled with.

In the EU context, the legal terms ‘EU regulation’ in English and ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament) ЄC’ in Ukrainian have become full equivalents with the same legal concept as their mental representation. Though this very concept is the same for the two legal terms in question, what makes them different is the system of concepts formed by the other concepts designated by the word ‘regulation’.

Apart from differences in semantic structures and systems of concepts expressed by SL term and TL term, there is another issue that makes the choice of the Ukrainian term doubtful. The word ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ is used as a Ukrainian equivalent of the term ‘rules of procedure’ in the same documents, which may cause a TT recipient’s confusion. Thus, in the text of the Treaty the term ‘rules of procedure’ is used 63 times, and in the Agreement we find it 16 times, each time this term is translated as ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’.

Example 19

The European Parliament shall adopt its Rules of Procedure acting by a majority of its Members | Євpoпeйcький Пapлaмeнт yxвaлює cвiй Peглaмeнт, дiючи бiльшicтю cвoїx члeнiв |

(TrFEU. Art. 232) |

The context does not help here understand if the Ukrainian term ‘rehlament’ is used to render the ‘rules of procedure’ or ‘regulation’.

The confusion gets worse if the same word is used to translate ‘regulation’ and ‘rules of procedure’ within one sentence.

Example 20

Each institution, body, office or agency shall ensure that its proceedings are transparent and shall elaborate in its own Rules of Procedure specific provisions regarding access to its documents, in accordance with the regulations referred to in the second subparagraph | Кoжнa ycтaнoвa, opгaн, cлyжбa тa aгeнцiя Coюзy зaбeзпeчyє пpoзopicть cвoїx пpoцeдyp тa вcтaнoвлює y cвoємy Peглaмeнтi cпeцiaльнi пoлoжeння cтocoвнo дocтyпy дo їxнix дoкyмeнтiв вiдпoвiднo дo peглaмeнтiв, зaзнaчeниxї y дpyгoмy aбзaцi |

(TrFEU. Art. 15) |

EU legislation has been intensively translated into Ukrainian for many years, and of 2,130 EU documents translated into Ukrainian, there are 653 Regulations, which is 30% [62, 67]. To translate the word ‘regulation’ into Ukrainian, the lexeme ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ was chosen and has been used to translate all EU regulations.

Comparing the semantic structures of the two terms in question (Table 5), we can see one component of meaning similar for both of them (both designate a procedure), however even in this meaning the English term has a different shade meaning and refers to rules and conditions determining procedures of any kind, while Ukrainian ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ denotes a procedure itself, and refers only to meetings, sessions, and other official gatherings etc.

The question arises why the translators of EU legislative acts made a decision to use the Ukrainian term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ for the title of EU ‘regulation’. The same term ‘regulation’ had been already translated into other languages, including French, Italian and other Romance languages where we find the equivalents, such as ‘règlement’ (Fr) and ‘regolamento’ (It). An assumption can be made that the EU regulations were initially translated from French,Footnote 1 and misled by the similarity in the graphical and phonetic structure of the word, a translator might have chosen the Ukrainian word ‘rehlament’ which cannot be considered equivalent to the English term in question.

As has been concluded above, a repeated use of the Ukrainian word ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ within the context of the EU legislation resulted in this word acquiring a new meaning and changing its semantic structure. Michael Hoey, speaking about lexical priming and translation, argues: “In accordance with the need to account for the existence of collocations, I claim that when we encounter language we store it much as we receive it, at least some of the time, and that repeated encounters with a word (or syllable or group of words) in a particular textual and social context, and in association with a particular genre and domain, prime us to associate that word (or syllable or group of words) with that context and that genre or domain.” [24: 155]. The lexeme ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ have been found in new collocations (see above). Hoey claims that “… collocations are not a permanent feature of the word (etc.). They may well drift in the course of individual’s lifetime. If they do, and to the extent that they do, the word (etc.) will drift slightly in meaning and/or function or in terms of the social context, genre and’/or domain in which it typically occurs. Drifts in the primingFootnote 2 of a community of speakers are the engine of language change.” [24: 155].

11 Conclusions

To sum up, the translatability potential of the legal term ‘regulation’ within the EU context is low-medium, as Ukrainian legal system does not have an identical legal concept; the lexeme ‘regulation’ is polysemic and is not only a legal term but is also found in everyday language and other specialised domains; in Ukrainian there are well-established equivalents of the lexeme ‘regulation’ but neither of them was used to translate EU regulation. The potential should be realised for the translation to be truthful, and if it is low, it is important to use all the options this potential gives. The choice of the Ukrainian term ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’ cannot be considered the best use of the options. As the concept analysis demonstrated, the system of concepts expressed by ‘regulation’ has different expressions in Ukrainian, except EU REGULATION, and the semantics of the two terms differ considerably, having only one component in common. However, the Ukrainian equivalent of EU regulation has been well-established and used to translate all the EU regulations since 1998, therefore ‘rehlament’ may be considered a conventional equivalent of ‘regulation’ within the EU context.

In the paper, the concept of translatability potential was substantiated and developed in the case study of the legal term ‘regulation’ and its Ukrainian equivalent ‘peглaмeнт (rehlament)’. They were considered in EU context and outside it. The study is interdisciplinary and though predominantly it is conducted within the translation studies, it also included the elements of contrastive lexicology, comparative law, corpus linguistics and conceptual linguistics.

The concept of translatability potential may be useful for the theory and practice of translation, as it will help translators identify the options presented by each term and make better decisions, and in doing so, improve the quality of the final product of their work. As the case study showed, the main factors that determine TP of a legal term are the availability of an identical or a similar legal concept in the target law system, the number of meanings in the semantic structure of the term, and the availability of well-established equivalents in the TL registered in specialised dictionaries.

This paper presented a system of concepts formed by the term ‘regulation’ actualised by means of different collocations of the term. The corpus of EU texts, compiled for the purpose of this research, made it possible to single out all the occurrences of the term in the said corpora and study it in all contexts.

The methodology developed in this study makes it possible to continue the exploration of translatability potential concept, investigate TP of linguistic units in legal discourse. The English-Ukrainian parallel corpus of legal texts can be used to analyse the functioning of legal terminology and its translation, study the issues of translation of specific EU terminology, the techniques of translating allomorphic lexical and grammatical units. It would be interesting to compare the translation of specific EU terminology into different European languages.

Notes

règlement (1) solution; (2) settlement; (3) regulations, rules; (4) by-laws https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/french-english/r%C3%A8glement.

The theory of lexical priming suggests that each time a word or phrase is heard or read, it occurs along with other words (its collocates). This leads you to expect it to appear in a similar context or with the same grammar in the future, and this ‘priming’ influences the way you use the word or phrase in your own speech and writing. (https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/american/lexical-priming).

References

Bassnett-McGuire, Susan. 1980. Translation Studies. London: Methuen.

Bassnett-McGuire, Susan. 1993. Comparative Literature. A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Bassnett, Susan, and André Lefevere, eds. 1992. Translation, History and Cultur. New York: Routledge.

Biel, Łucja. 2014. Lost in the Eurofog: The Textual Fit of Translated Law. Frankfurt am Mein: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-03986-3.

Biel, Łucja. 2014. The Textual Fit of Translated EU Law: A Corpus-Based Study of Deontic Modality. The Translator 20 (2): 332–355.

Biel, Łucja, and Dariusz Koźbiał. 2020. How Do Translators Handle (Near-) Synonymous Legal Terms? A Mixed-Genre Parallel Corpus Study into the Variation of EU English-Polish Competition Law Terminology. Estudios de Traducción. https://doi.org/10.5209/estr.68054.

Bajcic, Martina. 2010. Challenges of Translating EU Terminology. In Legal Discourse Across Languages and Cultures, ed. Maurizio Gotti and Christopher Williams, 75–93. Berlin: P. Lang.

Benjamin, Walter. 1992. Illuminations (tr. Harry Zohn). London: Fontana Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 1996. Selected Writings Volume 1. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Bohachov, Andrii. 2010. Mozhlyvist Perekladu (Possibility of Translation). Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 5–21.

Cao, Deborah. 2007. Translating Law. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Catford, J.C. 1965. A Linguistic Theory of Translation. London: Oxford University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1981. Positions (tr. Alan Boss). London: The Athlone Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1985. The Ear of the Other: Otobiography, Transference, Translation (tr. P. Kamuf). New York: Schocken.

El-Farahaty, Hanem. 2015. Arabic-English-Arabic Legal Translation. New York: Routledge.

El-Farahaty, Hanem. 2016. Translating Lexical Legal Terms Between English and Arabic. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 29 (2): 473–493.

Fischer, M. 2022. Horizontal and Vertical Terminology Work in the Context of EU Translations. Porta Lingua 1: 7–15.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 2010. Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1986. The Relevance of the Beautiful. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gentzler, Edwin. 1993. Contemporary Translation Theories. New York: Routledge.

Hacken, Pius. 2015. On the Distinction Between Conceptual and Semantic Structure. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 12: 507–526.

Halliday, Michael. 1973. Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward Arnold.

Hartman, Jenny. 2015. A Meaning Potential Perspective on Lexical Meaning: The Case of Bit. English Language and Linguistics 20 (1): 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674315000283.

Hoey, Michael. 2011. Lexical Priming and Translation. In Corpus-Based Translation Studies. Research and Applications, ed. Alet Kruger, Kim Wallmach, and Jeremy Monday, 153–168. London: Bloomsbury.

Holubovych, Inna. 2010. Untranslatability as a Natural Cause of Translation. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 154–156.

Honcharenko, Kateryna. 2010. Untranslatability as a Factor of the Development of Philosophy. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 148–153.

Jakobson, Roman. 1959. On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In On Translation, ed. Reuben Brower, 232–239. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Karaban V. I., and I. A. Rud. 2009. Do teorii anglo-ukrainskoho iurydychnoho perekladu. Movy ta kultury u novii Evropi: kontakty s samobutnist, 369–374.

Kebuladze, Vakhtang. 2010. Pereklad. Topos. Etos. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 22–31.

Khoma, Oleh. 2010. Filosofskyi pereklad s filosofska spilnota. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 49–66.

Liashchuk, A. M. 2008. Semantychna struktura leksyky na poznachennia poniat prava ukrainskoii ta angliiskoii mov. Kirovohrad: KOD.

Margolis, Eric and Laurence, Stephen. 2022. Concepts. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/concepts/.

Mattila, Hekki E.S.. 2012. Legal Vocabulary. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Law, ed. Lawrence M. Solan and Peter M. Tiersma, 27–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McAuliffe, Karen. 2012. Language and Law in the European Union: the Multilingual Jurisprudence of the ECJ. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Law, ed. Lawrence M. Solan and Peter M. Tiersma, 200–216. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Metthiesen, Christian M.I.M.. 2018. The Notion of Multilingual Meaning Potential. A Systemic Exploration. In Perspectives from Systemic Functional Linguistics, ed. Akila Sellami-Baklauti and Lise Fontaine. New York: Routledge.

Neubert, Albert, and Gregory Shreve. 1992. Translation as Text. London: The Kent University Press.

Nida, Eugene A.1964. Toward a Science of Translating. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Nida, Eugene A. and Taber, Charles R. 1969. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Norén, Kerstin, and Per Linell. 2007. Meaning Potentials and the Interaction Between Lexis and Contexts: An Empirical Substantiation. Pragmatics 17 (3): 387–416.

Nuopponen, Anita. 2010. Methods of Concept Analysis—A Comparative Study. LSP Journal 1 (1): 4–12.

Panich, Oleksii. 2010. Pereklad filosofskykh terminiv: filosofia and tekhnologia. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2010: 32–48.

Pavliuk, Nataliia. 2018. Translatability Potential of Legal Discourse Viewed from the Philosophical Perspective. Uluslararası Sosyal ve Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 4 (4): 35–50.

Pavliuk, Nataliia. 2019. EN-Ukraine Association Agreement: Challenges of Translation. Style and Translation 1 (6): 82–91.

Recommendations for Ukrainian Governmental Offices Regarding the Approximation of the EU Law [in Ukrainian]. https://eu-ua.kmu.gov.ua/sites/default/files/inline/files/legal_approximation_guidelines_ukr_new.pdf.

Russell, Bertrand. 1950. Logical Positivism. Revue Internationale de Philosophie IV 18: 3–19.

Saldanha, Gabriela, and Sharon O’Brien. 2014. Research Methodologies in Translation Studies. New York: Routledge.

Šarčević, Susan. 1997. New Approach to Legal Translation. London: Kluwer Law International.

Šarčević, Susan. 2012. Challenges to the Legal Translator. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Law, ed. Lawrence M. Solan and Peter M. Tiersma, 187–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shablii, Olena. 2012. Nimetsko-Ukrainskyi Yurydychnyi Pereklad [In Ukrainian]. Nizhyn: M. Lysenko.

Schalow, F. 2011. A Conversation with Parvis Emad on the Question of Translation in Heidegger. In Heidegger, Translation, and the Task of Thinking, ed. F. Schalow, 175–189. New York: Springer.

Snihur, S. 2003. Yurydychi terminy iak perekladoznavcha problema. Visnyk: Пpoблeми yкpaїнcькoї тepмiнoлoгiї 490:71–75.

Steinhauer, Karsten, and John F. O’Connoly. 2008. Event-Related Potentials in the Study of Language. In Handbook of the Neuroscience of Language, ed. B. Stemmer and H. Whitaker, 91–104. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Vasylchenko, Andrii. 2010. Perekladannia neperekladnoskyi: Semiotic problem and filosofikal metod. [in Ukrainian]. Filosofska Dumka (Philosophical Thought) 2: 138–147.

Verschueren, Jef. 2018. Adaptability and Meaning Potential. In The Dynamics of Language: Plenary and Focus Papers from the 20th International Congress of Linguists, Cape Town, July 2018, ed. Rajend Mesthrie and David Bradley, 93–109. Cape Town: UCT Press.

Other References

Types of EU Law (official website of the European Commission) [online] https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/types-eu-law_en. Accessed 20 April 2023.

Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union. [online] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT. Accessed 5 May 2023.

Treaty on European Union [online]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:11992M/TXT Accessed 5 May 2023.

Association Agreement Between the European Union and Its Member States, of the one part, and Ukraine, of the other part [online]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A22014A0529%2801%29. Accessed 11 December 2022.

Draft Law On Lawmaking [online]. https://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=72355. Accessed 15 April 2023.

Ukrainian Academic Dictionary [online]. http://sum.in.ua/s/reghlament. Accessed 11 March 2023.

European Union: General information, Structure, Law System. Dictionary. 2019, ed. Yu. Kononenko and I. Lubko. Cherkasy: Cherkasy National University.

European Legislation [online]. https://ips.ligazakon.net/resource/european_legislation?sort_by_def=date%20desc&sort_by=date%20desc&p=0&european_legislation=323-100.030. Accessed 18 February 2023.

The Free Dictionary [online]. https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/regulation. Accessed 12 March 2023.

Collins Dictionaries of Law. 2006. [online] https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/regulation Accessed 12 April 2023.

Collins English Dictionary [online] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/ Accessed 15 April 2023.

English-Ukrainian Law Dictionary. 2004, ed. V. Karaban. Vinnytsia: Nova Knyha.

English-French-German-Ukrainian Dictionary of the EU Terminology. 2007. Kyiv: К.I.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pavliuk, N. A Potential of Legal Terminology to be Translated: The Case of ‘Regulation’ Translated into Ukrainian. Int J Semiot Law 36, 2429–2454 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10034-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10034-x