Abstract

The present paper—taking the example of the English translation of the Hungarian Civil Code of 2013—aims to give an overview on the legal and terminology-related challenges and pitfalls that might occur during the process of translating a civil code with civil law traditions into the language of the common law world. An attempt is made to categorise terminology-related conceptual problems and elaborate how the different types of translation methods (functional equivalence, paraphrasing and neologism) could be applied; moreover, how a kind of legal-linguistic checks-and-balances can be achieved through the well-dosed combination, having also the ratio of similarities to differences (SD-ratio or SD-relationship) of legal concepts behind the respective terms in mind. Legal translators must act beyond the role of a simple translator: they must be comparatists, being aware of the legal origin of the relevant concepts and using the methods of comparative private law and translation studies at the same time, since both law and language are system-bound and are heavily influenced by the cultural and social environment. The authors strive to identify the significance of those problems (and possible solutions) from the perspective of how language-related aspects can perform some fine-tuning on the comparative methodology and findings, whether they are barriers only or provide also an opportunity to verify or refute prima facie comparative results. Comparative law—no doubt—supports legal translation, but their relationship is reciprocal: legal-linguistic subjects and problems emerging in the course of legal translation supply valuable feedback and further sources of inspiration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Legal systems, the legislation of which is drafted and enacted in a language, which is less widely used and understood, suffer from isolation as they cannot be directly accessed by legal practitioners or scholars from other countries. Therefore, the various legal solutions of these legal systems can hardly be perceived as models and cannot easily be transplanted into other legal systems and, in the same way, their legal concepts can hardly if ever receive any international feedback or reflections. For that—and if these legal systems with “exotic” languages do not want to drop out of the international academic community—they must be explained in the legal literature in another language and/or translated into a lingua franca. The most efficient way is most probably to have a combination of both. The lingua franca of law and of any other sciences today is definitely English. As Grosswald Curran points out: “English has gained ascendancy, if not dominance, with international exchanges in a field increasingly conducted solely in that single language, whether in scholarly conferences, in journals targeting an international readership, or in university classes where professors and students do not share a native language.” [1: 682] “Efforts to reverse or even halt the trend to use English, to the extent they still are being made, seem to be as ineffective as efforts to defend any one language from foreign importations within it.” [1: 698] As far as law and jurisprudence are concerned, this is the language in which international commercial contracts are drafted, international trade works and most international agreements are drawn up. It is therefore self-evident that if national legislation is to be translated, it should be into English.

Translation—and let’s quote again Grosswald Curran—is “both de-coding and re-coding, identifying and constructing meaning.” However, by no means all associations of a word in one language can be transposed into the other; therefore a loss of connotative significance cannot be avoided. “As best, translation achieves an overlap of some meanings between two domains, as in an intersection of sets, but not total overlap, as in a union of sets.” [1: 685] This stands even more true and is not without challenges as far as translating legislation is concerned, especially in the field of private law, where considerable differences exist between legal systems, above all between those that belong to common law traditions and those that are part of the civil law world. The difficulty of translating a civil code of a country with civil law traditions into English lies in the challenge of expressing concepts of civil law in a language with a legal vocabulary that is intimately connected to common law. Of course such an exercise is not without precedents; several civil codes have already been successfully translated into English and the English translation of the German BGBFootnote 1 or that of the Swiss Civil Code (Schweizerisches Zivilgesetzbuch, ZGBFootnote 2) and Law of Obligations (Obligationenrecht, ORFootnote 3) can serve as a source of inspiration for other countries coping with the difficulty of expressing certain concepts of their private law in English. However, each country must go its own way in this process, in which translators and legal revisers must clearly act beyond the role of a translator: they must be comparatists, being aware of the legal origin of the relevant concepts of the code and using the methods of comparative private law and translation studies at the same time with the same ease [2: 75–76]. That was reinforced by the experience of drafting a publicly available English version of the new Hungarian Civil Code (HCC),Footnote 4 an exercise undertaken under the auspices of a comprehensive translation project managed by the Hungarian Ministry of Justice in order to make the most important pieces of the national legislation accessible in English.Footnote 5

This paper will make an attempt to categorise terminology-related conceptual problems in this exercise and explain how the different types of translation methods (functional equivalence, paraphrasing and neologism) could be applied. The authors have the ambition of going beyond the discovery of the primary goals of legal translation and to identify the significance of those conceptual problems (and possible solutions) from the comparative law perspective: how language-related aspects can carry out some fine-tuning on the comparative methodology and findings, and whether they are barriers only or provide also an opportunity to verify or refute prima facie results.

1 On the difficulties of legal translation in general

The difficulties immanent to the translation of legal texts (legislation, contracts, judicial decisions) have always been in the focus of both translation studies and legal research. Harvey has even described it by referring to several other authors as the “ultimate linguistic challenge”, with regard to which the real difficulty of translation actually lies in the need to combine the “inventiveness of literary translation with the terminological precision of technical translation” [3: 177]. Legal translation is indeed mostly influenced by the fact that both law and language are system-bound and are heavily influenced by the cultural and social environment in which they function. Moreover, a single natural language can serve as the language of several legal systems at the same time—some of them not even belonging to the same legal family—thereby multiplying the legal languages expressed through the same natural language. In addition, with the proliferation of international documents and especially with the emergence of European Union law, these legal languages (and before all their vocabulary) must be able to express new system-specific legal concepts or conceive and interpret existing legal concepts in a different, supranational context and level. Thus, legal languages still remain system-bound, but bound to not only a single but more than one system.

It is due to these specificities that de Groot maintains that, in legal translation, full equivalence can never be achieved between the concepts of different legal systems but only approximate equivalence, which however should suffice for the purposes of legal translation [4: 228]. Similarly, Šarčević submits, with the aim of redefining the goal of legal translation, that “the translator should strive to produce a text that is equal in meaning and effect with the other parallel texts, whereby the main emphasis is on effect” [5: 72]. However, Fischer urges that this classical approach to legal translation be fine-tuned when she underlines that, with globalization and various attempts to unify legal provisions, it is no longer true that legal translation only occurs in relation to two distinct legal systems and the conceptual frame in which they operate [6: 70, 176].

Legal translation is however in itself a complex process and is strongly influenced by several factors, such as the nature of the legal text to be translated, the purpose of the translation and the identity of the source and the target language. Therefore, there have been several attempts to establish categories for the different types of legal translation. Cao’s classification is based on the well-known categories Kelsen uses in his work, the General Theory of Law and StateFootnote 6 identifying prescriptive and descriptive—in other words performative and informative—legal texts [8: 10]. Cao establishes three larger categories of legal translation: the translation of private legal documents, the translation of domestic legislation and that of international legal instruments. In each category, translation might pursue performative or informative purposes. The translation of a contract, which should be binding in several languages, should be considered as a translation of private law documents with performative purposes while the translation of a marriage or birth certificate has an informative purpose. Similarly, if domestic legislation is official in several languages, the purpose of the legal translation is performative, while in all other cases the translation of national legislation can only have informative goals. The same distinction is drawn in the case of those international agreements that are authentic and binding in several languages and those translated for informative purposes only [9: 5–7]. Whether the translation of a legal text is for informative or performative purposes can have an impact on the usefulness of the various translation methods and thereby on the choice of which one shall be preferred: in the case of informative texts, paraphrasing or descriptive methods can be more easily used while for performative texts the terms used should be put in a simple but precise way by avoiding lengthy explanations.

The difficulty of the translation process itself depends strongly on the remoteness of the source legal system from the legal system, the language of which will be used as target language throughout the translation and on the proximity of the languages themselves [4: 229]. Equivalence in terminology in the case of closely-related legal systems will certainly be more approximate or even full [8: 9] while equivalence is hardly achievable when translating legislation of a civil law-based legal system with a non-Germanic language into a language that is typically the language of common law.

However, it should be noted that English as a legal language has undergone substantial neutralization during the past decades while it became the language of various international documents, the drafting language of international business contracts and one of the official languages of the European Union, and therefore it is less system-bound than any other legal language and already uses terminology distinct from common law in certain areas. Moreover, some authors call this tendency a kind of modification beyond neutralization in the form of new words beyond the boundaries of the common law context “spawned by concepts of civilian origin” [1: 698].

2 The recourse to traditional and non-traditional translation methods in the case of the Hungarian Civil Code

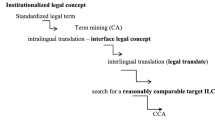

The translation of the HCC into English should be classified as a translation with informative purposes into a language that is the official language of common law legal systems but at the same time an evolving legal lingua franca. In the course of such an exercise, the most essential element is to have a coherent approach towards establishing equivalence in terminology by trying to point out differences and similarities between legal concepts in the source language and in the target language. In that regard, a noteworthy new method has been proposed by Matulewska, known as parametric theory, based on the characterization of legal translation reality and translational objects and relations functioning in such a reality with the help of elaborating potential dimensions (parameters) specifying a space for an examination of the translation reality [10: 12]. In a comprehensive study, Matulewska selected relevant legal terminology from the Polish Civil Code and Civil Procedural Code and, with the help of parametrization, she aimed to establish fully and partially equivalent terms in six other languages [10: 15].

During the translation process of the HCC, no such specific method was used for finding terminological equivalents but the relevant terms (approximately 1100 terms) were selected and examined individually in the light of the classical translation methods—identifying functional equivalents, paraphrasing or creating neologisms—whereby the best applicable and suited method was applied depending on the origin, context, historical and conceptual background of the term.

Moreover, regard had to be taken of the fact that the HCC is embedded in the entire bulk of Hungarian legislation, and as such it utters terms that are not pure civil law terms but stem from other legal acts adopted in neighbouring fields of law. Therefore, the establishing and safeguarding interdisciplinary coherence had to be a compulsory aspect of the translation exercise and accompanying research work.

It should still be stressed that the nature of the source text (being a legislative act) excluded the recourse to alternative methods, such as giving more detailed explanations in footnotes or by another way on the various aspects—such as relevant case-law, doctrinal interpretation—of certain legal institutions specific to the Hungarian legal system, as the translation had to respect the textual integrity of the original code.

Below, we will illustrate with examples chosen from the selected 1100 terms of the HCC what kind of considerations had to be assessed and balanced when having had recourse to the various translation methods, in which cases the individual methods proved to be successful and when should they be set aside.

2.1 Functionalist approach

When following the functionalist approach, the translator seeks to identify the term of the target legal language that is most fit to express the concept of the source legal system. Such an exercise presupposes the knowledge of the legal systems concerned and compared in order to find the equivalent. However, as de Groot very correctly points out, it is almost impossible to find full equivalents if the source legal system and the legal system of the target language differ substantially [4: 229]. Even basic concepts of the law which, according to their core function, are identical might show substantial differences. A contract to be formed in a common law country would always require consideration, while in civil law systems no such requirement appears. However, there would be no reason to translate a Vertrag in German law otherwise than contract, as the essential function of both concepts—that is to have a mutual and enforceable agreement between the parties—is the same. As Šarčević submits, the closest functional equivalents should be used in legal translation if any differences in concepts are not decisive [5: 237–238]. Should major differences be identified, however, the use of presumed equivalents is risky, as it can trigger erroneous associations and interpretations. If there is no exact equivalent, the expressions concerned cannot be translated but rendered by means of approximation. The more differences can be identified, the more lengthy explanations were needed to avoid a misleading impression of similarity to the readers’ own legal system. However, (translated) legal texts hardly if ever tolerate “an encyclopaedic volume of explanations in the footnotes.” [1: 684].

In order to deal with equivalents properly, the translator must, above all, be aware of where the legal concepts of the source legal system come from: are they transplants of concepts of an influent legal system, have they been inspired by internationally agreed model rules or are they concepts peculiar to the source legal system? The choice of words must be made in the light of these findings. This is what was done for those terms of the HCC for which functional equivalents could be found. Throughout this exercise, the origin and the traditional roots of the relevant concept had to be identified properly in order to avoid an eventual mismatch with presumed functional equivalents, while in other cases a significant overlap in core functions was deemed to be sufficient in order to favour functional equivalents to neologisms. The examples below illustrate cases where functional equivalents were picked for the purpose of translation.

Unjust enrichment under common law was, for instance, not considered an appropriate equivalent of the Hungarian jogalap nélküli gazdagodás,Footnote 7 a concept derived from the German ungerechtfertigte Bereicherung based on the Roman law concept of condictiones (sine causa) but mixed with the idea of restitution [11]. The common law concept is, by name, completely independent from the existence of a causa but instead requires the claimant to point to a particular unjust factor or grounds for restitution, while the Hungarian concept refers to the lack of a valid and lawful legal title [12: 234]. Moreover, the English concept seems to be broader. It is often argued, for instance, that in English law almost all restitution claims are based on unjust enrichment while the German type of unjustified enrichment is only one amongst several models allowing restitution as remedy [13: 13–19]. In that regard, unjust enrichment appeared as a false friend and the correct translation was found to be a formulation that expresses the difference from the common law concept. Hence, the term unjustified enrichment—widely used in the legal literature [14]—was chosen as an appropriate translation, despite the fact that in international documents or available translations of national laws unjust enrichment is often used as an approximate functional pair for the German-type legal institution.Footnote 8 In this case the endeavour of the translators of the HCC was to avoid imperfect matches and underline substantial functional differences.

On the contrary, the concept of előreláthatóság in the HCC, delimiting the boundaries of damages in the case of a breach of contractual obligations,Footnote 9 was explicitly borrowed from common law and international documents, which transplanted it [15: 85–111]. Here, no other term than foreseeability could have been used in the English translation. Linguistically correct versions, such as predictability, would have been misleading and legally meaningless. This stands true, despite the fact that common law traditionally uses foreseeability in the area of tort law and originally uttered another (or parallel) term in the field of contractual damages instead, called “reasonable contemplation” [16: 1809]. However, when transplanted to international instruments of harmonisation in the field of contract law, the term “foreseeability” was chosen by all the drafters. The concept was clearly inspired by the common law model, even if it does not completely overlap with it [17: 17]. As the Hungarian concept is a legal transplant based on one of the above international instruments, the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), the choice of the term was dictated by the transplantation itself. A peculiar feature of the Hungarian system is that the new HCC is not only using előreláthatóság (foreseeability) in the field of contractual damages but also with regard to extracontractual liabilityFootnote 10 and therefore, from a linguistic and conceptual point of view, the translation of the same term used in the two different contexts had to coincide.

The above two examples show that recourse to the well-established common law vocabulary depends on the origin, role and similarity in function and purpose: certain terms must be avoided while others appear as the only acceptable equivalents.

Moreover, the already available English language vocabulary is not even in itself perfectly uniform. The question immediately emerges of which legal system should serve as the basis of comparison if English is the target language: that of the United Kingdom, that of the US or Australia or the legal language used in international or European instruments of harmonisation, the English version of the civil law of Québec or the English used in informative translations of the civil codes of civil law countries? As the purpose of the translation process in this particular case was to provide general information on the Hungarian rules in private law, the audience targeted by the translation was not primary a common law-educated circle but an international legal community. Therefore—where applicable—international documents, such as the Principles of European Contract Law (PECL),Footnote 11 the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts,Footnote 12 the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG),Footnote 13and the Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR)Footnote 14—could be used as a source of inspiration. Rules with a background of international conventions (with special regard to international trade) and soft laws are likely to be accepted more easily anyway and with a bigger prospect of success, because they were negotiated amongst many countries to meet their needs with the involvement of other organizations, actors and stakeholders, and represent acceptable compromises. Terms used therein are more widespread and known for the same reason [18: 485]. As with international documents, so could the semi-official translations of civil law-based legal systems, such as the English version of the (German) BGB and the (Swiss) ZGB and OR, be used as another source of inspiration.

Given the fact that most of the international instruments aiming to set commonly agreed and accepted legal rules emerged in the field of contract law, certain concepts of the contract law of civil law countries have already been introduced to the international legal community through a commonly agreed, mostly artificial name, which—even if not widely used—was at least known to legal practitioners and academics around the world. Therefore, it was quite evident that in these areas this consensus-based terminology should be followed throughout the translation of Book 6 (Law of Obligations) of the HCC. This way early performance,Footnote 15modified acceptance,Footnote 16agency without authority,Footnote 17restoration of the previous/original situation,Footnote 18 and good faith and fair dealingFootnote 19 could easily be used in order to exhibit the appropriate concepts of Hungarian contract law. Likewise, in the case of specific legal institutions that exist in some other legal orders but do not have equivalents in common law or have not been used in international instruments, the terms used in the English translation of the national codes of those other countries familiar with the concept could serve as an option. The German Werkvertrag, the subject-matter of which is either the production or alteration of a thing or another result to be achieved by work or by a serviceFootnote 20 and which is not known in the common law as such a specific type of contract and is not regulated in international instruments, was translated in the German version of the BGB as contract to produce a work. As the Hungarian vállalkozási szerződés should be seen as a functional equivalent of the German WerkvertragFootnote 21 the English translation of the BGB was used in the Hungarian translation.

Solutions to be found in the translations of national civil codes gain an even greater importance in areas lacking international harmonisation attempts. Given the similarities between the German and Hungarian law of succession, the English translation of the relevant terminology of the BGB could be taken over to indicate legal institutions having the same objective or purpose. Thus, the terms compulsory share, renunciation of inheritance, and testamentary disposition are used appropriately in the English version of the HCC.

These translations can also work as source of inspiration for deciding upon the use of approximate equivalents of common law terminology in specific cases. Although it was questioned in the legal literature whether the German term Gegenleistung could be properly rendered with the English term consideration not being able to express the essence of the original concept lying in the dichotomy of service and counter-service [19], the English translation of the BGB opted for considerationFootnote 22 and preferred to use an approximate, not perfectly matching equivalent instead of an artificially created term. For the translation of the HCC, in which ellenszolgáltatás is a mirror translation of Gegenleistung with same central significance as in German law, using consideration and following the German translation seemed to be a logical choice. Nevertheless, it shall not be ignored that the term and concept of consideration in English law has a much broader and deeper meaning than just something given in return. Unless a promise is made by deed, contractual liability and enforceability is only incurred when “such undertakings are part of an interlocking exchange in which each party’s promise or performance is the agreed equivalent and inducing cause of the other’s” [9: 209]. In other words, the existence of an enforceable obligation depends on consideration. Some rough-and-ready rules are connected thereto: consideration must have some economic value in the eyes of the law, i.e. it shall be sufficient but not necessarily adequate; consideration must move from the promisee (plaintiff) and must be some detriment to the plaintiff or some benefit to the defendantFootnote 23 [20: 97, 21: 69–70]. Emphasis is put on reciprocity [21: 67], because this is the best justification for the contract’s expectation remedies and the limited excuses for non-performance; moreover, it must be explicitly required (in the form of consideration), because transactions in the market domain “lack the implicit reciprocity of transactions in the private domain” [22: 229]: therefore consideration “is the price paid by the plaintiff for the defendant’s promise” [23: 97, 104, 106]. That’s why consideration gives English law the notion of contract as a bargain [24: 118]. According to the prevailing view, there is no consideration where a public duty is imposed upon the promisee by law or he is bound by an already existing contractual duty to the promisor (past consideration is no good as consideration), but there is consideration if the plaintiff is bound by an existing contractual duty to a third party [23: 115, 117, 137, 24: 124–125, 21: 73, 83]. Of course, the boundaries and functionality of consideration are not without controversies in the English scholarship. Atiyah criticises it for being “a technical requirement of the law which has little or nothing to do with the justice or desirability of enforcing a promise” [25: 185]. Though benefit, detriment or bargain are indeed taken into account if the enforceability of an agreement is at stake, it is however not because they fit into the artificial concept of consideration, but much more because they serve as material factors in determining “whether it is just or desirable to enforce a promise” [25: 187]; in sum, “consideration has been cut loose from the reasons underlying it, so that it almost necessarily becomes a technical and purposeless set of arbitrary rules” [25: 191]. There is no further or deeper analysis needed on consideration for the purpose of this paper, because as much has been said so far to be sufficient to give rise to doubts whether it was a good idea to use the term consideration in the English translation of civil codes of civil law jurisdictions. This indicates another question: how much and how deep a comparative knowledge shall be and can be expected from the readers of the translation and, finally, how significant is the risk that the closest equivalent misleads them and, for example, readers with a common law background may think that consideration in the German, Hungarian, etc. civil codes has the same significance regarding the conclusion of (enforceable) contracts and involves the same controversies as in English law. To our understanding, the translators’ hope of not having caused more confusion than if they used a neutral but completely artificial term is not wholly unfounded, since it tends to be part of lawyers’ general legal knowledge, regardless of background, that it is mutual consent on which contracts (and their enforceability) are based in civil law jurisdictions and not whether there is anything to be given in return.

Inspired by the English translation of the ZGB, similarity in essential functions in civil law and common law concepts was relevant when deciding to use public deed for authentic documents or instruments (közokirat in Hungarian and öffentliche Urkunde in the German version of the Swiss lawFootnote 24), despite the differences in the establishment and production of such documents in civil law and common law systems.Footnote 25 Using an artificial descriptive translation in this case would have been meaningless for the reader. Moreover, public deed seems to be commonly used already by other civil law jurisdictions in English language legal books, papers and translations.Footnote 26

It is with the same purpose and endeavour that the term juridical act, introduced and used as a core term of the DCFRFootnote 27 for statements or agreements, whether express or implied from conduct, which are intended to have legal effect as such, was taken over to the English translation of the HCC, despite the fact that the juridical act of the DCFR seems to be broader than the Hungarian term.Footnote 28

As demonstrated, functional equivalents of common law terminology might prove adequate if the essential functions of the concepts are identical and the context makes the non-essential characteristics clear while, in the case of transplants of common law concepts, the use of functional equivalents is a must. At the same time, English terms devised at national or international level in order to exhibit civil law concepts can and, in the interest of making this vocabulary uniform and widespread, should be followed in new translations of civil codes. As explained and seen regarding the triangle of ellenszolgáltatás, Gegenleistung and consideration, the use of the closest equivalent may and can sometimes be considered the least worst solution, even if it is quite far from the term to be translated and from the concept of the language of the origin to be reflected in the target language; and even if the scope of the latter is significantly broader and denser than the term in the language of origin, since the lack of understanding may be more misleading and confusing than some misunderstanding based on the conceptual (common law) background of the term used in the target language.

2.2 Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is a useful means of avoiding mismatches of remote functional equivalents or conceptual false friends by describing the given legal institution. Paraphrasing is thus driven by precision, and the descriptive method might help to explain the essential characteristics of the concept. However, this advantage appears at the same time a disadvantage, because the descriptive formulation might sound alien in the whole body of the law and might burden the text. Nevertheless, using the method of paraphrasing can still draw the readers’ attention to the “otherness” and can motivate the reader to look for further sources that reveal the content and the exact meaning of the respective rule, principle or legal institution. The bigger the gap between the content and meaning of the original term and of the “closest” equivalent in the other language, the more reasonable it is to switch to the technique of paraphrasing, unless the use of the closest equivalent equals the least worst solution for some particular reason inherent in the respective terms and concepts (see, for example, “consideration” above).

In the translation process of the HCC, paraphrasing was only used if the relevant term seemed to be non-translatable or if it was important to avoid a functional mismatch.

This descriptive method was successfully used in the introductory provisions of the HCC in the case of Section 1:1, aiming to define the scope of the Act and the main principles of private law that must be observed throughout the application and interpretation of the Code. The translation of the principle of equality (egyenlőség elve in Hungarian) did not pose major difficulties but the other principle, aiming to underline not only the equality but also the lack of interdependence and the same level-based status of the actors in private law (mellérendeltség elve in Hungarian) did not have a well-elaborated perfectly matching equivalent in other legal systems. Therefore, the descriptive method was used and the term mellérendeltség, which means juxtaposition literally, was translated as non-subordination. Thus, the English version of the very first provision of the HCC provides “This Act governs the property and personal relations of persons in accordance with the principles of non-subordination and equality.”

Paraphrasing was also partly used in order to distinguish the different forms of the dissolution of a contract. Section 6:212 regulates the dissolution of the contract by mutual agreement of the parties: they might dissolve the contact for the future (ex nunc) or rescind it with retroactive effect (ex tunc). Section 6:213 foresees the parallel legal effects in the case of unilateral juridical acts of the parties: if cancelled, the rules on rescission apply; if, however, unilaterally terminated, the contract is dissolved for the future. In this context dissolution, cancellation and rescission are existing legal terms of English (common law) private law, but unilateral termination (i.e. adding and emphasising unilateral) is a paraphrase in order to underline the independent aspect of this form of dissolution (the other party’s consent is not needed to dissolve the contract), which the term termination would not have been able to express on its own (i.e. without the addendum unilateral).

No method other than paraphrasing was advisable to be used in the case of the Hungarian transplant of trust which—unlike its common law parent concept—had to be envisaged under Hungarian law as a type of contract (bizalmi vagyonkezelési szerződés). As the original Hungarian term is already a paraphrasing, the English translation had to reflect this alteration and acculturation of the transplant by indicating it as fiduciary asset management contract. The origin of the transplant is however still reflected by the names used for the parties of the contract: the settlor and the trustee and the things, rights and obligations transferred to the trustee (trust property). The use of the term fiduciary asset management contract can be perceived also as an exclamation mark, drawing the reader’s attention to the conceptual and structural differences between the “classic” common law concept of trust and the civil law counterpart. In the Roman law-based civil law jurisdictions the unity of ownership prevails; the simultaneous existence of a legal and an equitable title (i.e. horizontally divided, dual or split ownership) does not and cannot exist [27: 1190, 1193, 1215]. Therefore, paraphrasing (and avoiding the use of the term trust) can have a secondary function, to support the correct interpretation of the respective rules and to assist in resisting the temptation to project any common law characteristic to the fiduciary asset management contract. In this way, the significance of translations can go beyond their primary function (making a legal text accessible to non-natives) inasmuch as conclusions can be drawn from a translation (why the term was translated exactly in a way as it was and what does this reveal about the meaning and/or on the distinction of the term from other legal institutions and false friends) regarding the content and merit of the respective rule, even in domestic use (the so-called blowback-effect of translation in domestic interpretation of the translated rule). Having this in mind, the use of the terms settlor and trustee seems to be prima facie contradictory, since it seems to push the respective phenomenon back towards the common law approach and to cause confusion on the legal nature of the type of contract in question. However, trust as a legal term in a broader sense goes beyond the notion in the narrow sense referring to the common law approach defined by equitable ownership. The former also covers different legal instruments (i.e. civil law adaptations) “that fulfil the function of property management” for someone else [27: 1189], i.e. that include the separation of assets from the trustee’s own property and other property managed (and owned also in his or her capacity as trustee of other settlors); the recognition of rights for the beneficiary against any third persons “in the case of gratuitous transfer of property or its acquisition with bad faith” corresponding to the common law concept of tracing; and, last but not least, the restrictions and limitations of the trustee’s rights to manage the property but not being allowed to dispose of it for any other purpose. The civil law adaptability of the trust’s functions shows that the common law approach on horizontally divided ownership is not a precondition of the trust’s functional essence [27: 1193–1194, 1211, 1215–1216]. To our understanding, the translators of the Hungarian Civil Code chose the right approach: again, the use of the paraphrase fiduciary asset management contract serves as an exclamation mark, warning the reader that the respective type of contract itself differs substantially from the common law fundaments of trust, thus the reader will not be misled into the common law concept of trust. After this semiotic red-line, it makes sense to stop paraphrasing and to remind the reader of the functional similarities by calling the parties settlor, trustee and beneficiary. When the translator opted for the use of these terms, he or she did not refer to the common law trust, but to the broad and international meaning of the term.

2.3 Neologism

Neologism means the artificial creation of a new term in the target language that would obviously not have a fixed meaning therein, and so it is perfectly suited to expressing the special nature of the concept of the source legal system, which lacks approximate equivalents in the target legal language. The novelty of the term will prevent eventual confusion with existing legal concepts of the target legal language but at the same time—unlike paraphrasing—it will not reveal anything about the substance and nature of the legal institution concerned. (In this way, neologism is not very different from leaving the term in the source language.) While there is no doubt that a neologism does not transmit the concept behind the term, it still indicates that “the concept at issue is foreign and without exact equivalence” [1: 684].

Some neologisms in the English legal language expressing concepts of civil law are already well accepted due to harmonisation and globalisation, such as the terms legal person (instead of earlier used nominations of juridical person or legal entity),Footnote 29personality rights (instead of the common law equivalents rights of publicity and/or rights of privacy),Footnote 30 and therefore, when translating the HCC, those concepts that are peculiar to the Hungarian private law were primarily considered for potential neologisms, either traditional or newly created ones. Subject of law, a person who has rights and obligations under the law, is such a neologism.

Title IX of Book 7 (Law of Succession) of the HCC regulates lineal inheritance and, within Section 7:67, deals with lineal property.Footnote 31 Both concepts are specific to the Hungarian law of succession rooted in old customary traditions [28] with the aim of ascertaining that assets passed to the deceased person from one of his ancestors through succession or gifting shall be subject to lineal inheritance (that is to say inherited by the parents or their descendants and not by the spouse or registered partner) if the intestate heir is not a descendant of the deceased. The English terms used for the relevant Hungarian concepts (ági öröklés, ági vagyon) had therefore to be artificially created.

An artificial term was created for the newly introduced form of compensation—called sérelemdíj and translated finally as grievance award—that replaced the former concept of non-material (or non-pecuniary) damages in the event of any breach of personality rights, because the concept of non-pecuniary damages in the former civil code was very much stressed by inherent contradictions. That’s why the legislator decided to replace it with sérelemdíj, always to be paid in a lump sum (thus, no annuity, i.e. periodical payment is possible), which is conditional on any personality right infringement (personality rights are covered by a general clause in Section 2:42Footnote 32 and by a non-exhaustive list in Section 2:43Footnote 33HCC; new personality rights can be and continuously are identified in case law). According to this new concept, however (and in contrast with the former approach on non-pecuniary damages), no proof of any (immaterial) disadvantage or loss has to be provided beyond the infringement of a personality right.Footnote 34 Section 2:52 Para 3 contains the factors the judge will consider while deciding on the amount, generally at their free discretion. These are as follows: the circumstances of the case, in particular the gravity of the violation, whether it was committed on one or several occasions, the degree of fault, and the impact of the violation on the aggrieved party and his environment. This grievance award can be claimed personally only; the claim cannot be inherited, unless the lawsuit is already filed with the court when the injured party passes away. Though the Hungarian sérelemdíj is a parent concept of the German or Austrian Schmerzen(s)geld, it is not identical to it therefore the English terms artificially invented and created for that concept (smart money,Footnote 35compensation and satisfactionFootnote 36) would also have been neologisms (even if already existing ones) but, given the substantial differences with their counterparts, at the same time misleading.

As far as the German and the Hungarian concept is concerned, there are differences both at the structural level and regarding some important details. While the Hungarian approach focuses on personality rights and on their infringements and the legislator created a presumption that personality right infringements do cause non-material harms to the victims (personality right approach), both the German and the Austrian concepts highlight the non-pecuniary losses (non-pecuniary damages approach). For example, Section 253 Para 1 of the German BGB clarifies that “Money may be demanded in compensation for any damage that is not pecuniary loss only in the cases stipulated by law.” Such a law follows directly after, in Para 2 of the same Section, stating: “If damages are to be paid for an injury to body, health, freedom or sexual self-determination, reasonable compensation in money may also be demanded for any damage that is not pecuniary.” While the Hungarian rule is quite open by contrast, reasonable compensation under German law can only be claimed if the specified protected goods were infringed and this caused non-pecuniary loss, harm or damage to the victim. The burden of proof lies with the plaintiff [31: 21, 30]. (The BGB does not even use the expression Schmerzensgeld, though this is widespread in case law and scholarly writings). The same stands true for the Austrian General Civil Code (ABGB): its Section 1325 makes it clear that Schmerzengeld can be claimed only if the victim suffered personal (bodily) injury (Körperverletzung).Footnote 37 Although the German case law developed an autonomous and independent claim for Schmerzensgeld based on Arts 1 and 2 Grundgesetz (Fundamental Law, i.e. the Constitution) in connection with Section 823 Para 1 BGB on extracontractual liability with reference, in case law, to the infringement of the so-called allgemeines Persönlichkeitsrecht (general personality right), but not even this is as flexible and wide open as the Hungarian counterpart, because under the constant case law in Germany, the personality right infringement must be grave and shall not be able to be eliminated or outbalanced by other types of claims, such as injunction, counter-order, right of reply, pecuniary damages, etc. (principle of subsidiarity) [31: 26–27, 32: 294–295, 311–312]. In sum, the German approach is much more restrictive. As far as the details are concerned—having regard to case law, i.e. to the law in action—there are also some significant differences. Though in all three legal systems the judge can establish the amount generally at his or her free discretion having the criteria specified in the civil code or developed in case law in mind (always with special regard to the circumstances of the particular case), in Austria and Germany, non-binding Schmerzensgeldtabellen (charts based on earlier published judgments) are continuously published and referred to in proviso jurisprudence and in litigation. Though the commentaries in both countries underline that the judges shall (must) not use these guidelines in a mechanical way and they always have to keep an eye on the circumstances of the particular case, the Schmerzensgeldtabellen nevertheless contribute significantly to the everyday predominance of the principle that similar injuries deserve similar amount of Schmerzensgeld and to the predictability of the law [31: 36–37, 35: 27, 30]. In Austria, for example, the daily amounts are adjusted to the gravity of the pain: i.e. they are different as far as light, intermediate, strong and excruciating pain and suffering is concerned [36: 30, 37: 72, 38: 33, 39: 117]. There are no such or similar published guidelines in Hungary. Though lump sum compensation is the rule in the two countries referred to here, in contrast with the Hungarian law, periodic payment (annuity) is not excluded provided this is in line with victim’s best interest due to the longevity, gravity and/or irreversibility of the pain and suffering he or she is exposed to (for example paraplegia) or to the unpredictability of the (non-material) consequences of the injuries. [31: 57–59, 36: 34, 38: 37, 39: 121]. Again in contrast with the recent Hungarian recodification, both German and Austrian laws allow the heirs to enforce the claim (in Germany, the one based on Section 253 BGB but not the other one based on the infringement of the general personality right), even if the victim had not filed the lawsuit yet when he or she died [31: 65, 32: 296, 36: 35, 37: 91, 38: 31, 39: 123]. The scope of the common law term pain and suffering is basically also restricted to the consequences of personal injuries. To be more precise, there are two types of non-pecuniary losses resulting from personal injuries to be compensated in English law: on the one hand pain and suffering, and on the other hand loss of amenity. Pain and suffering cover “pain, distress, anxiety and suffering experienced by the victim, but not sorrow or grief” [40: 21]. Consequently, pain and suffering does not fit into the broad concept of the Hungarian sérelemdíj either, which covers all kinds of personality right infringements, including but not limited to personal injuries, to the violation of privacy, good reputation and honour, to discrimination, to the unlawful use of someone’s image and recorded voice, etc. In addition, it should be stressed that legal scholars have warned of translating the German Schmerzensgeld as compensation for pain and suffering, as even the German concept is broader in encompassing other common law headings of damage, such as loss of amenity, disfigurement and loss of expectation of life [34: 198]. Since neither the approximate counterpart in English law, nor the German and Austrian concepts (and their translation) are equal to the Hungarian model, a new term, grievance award, was artificially created and inserted into the English version of the HCC.

Whether neologism will succeed and will be effectively used in legal practice and literature is a matter of time. It seems, for instance, that earlier attempts to call Hungarian legal persons established for the pursuit of business-like activities business associationsFootnote 38 failed in practice, and in business relations and in legal practice the use of the closest functional equivalent of companies was preferred, despite the fact that the concept of company in UK law definitely does not cover all types of existing Hungarian forms. General partnerships or limited partnerships under Hungarian law for instance would not count as a company under UK law, given the fact that these forms—similar to UK partnerships—are essentially based on the internal informality of their members as partners [42: 305] and, unlike private or public companies limited by shares, they cannot function with a single member. In the UK, companies and partnerships (even those with limited liability and being recognised as a legal entity) are clearly distinctly treated categories, regulated in different parliamentary actsFootnote 39 without an umbrella term that would cover all of them, while the HCC treats both of these entities under a single, rigid and specific cover-category (gazdasági társaság).Footnote 40 The Hungarian translation finally chose to follow the practice and used the closest functional equivalent of companies, instead of the earlier term business associations, which could not be accommodated. This approach is fully in line with what Šarčević submits: approximate equivalents should—if possible and they are not misleading—be favoured over neologisms [5: 262]. However, as referred to above, there are no perfect equivalents; there are more-or-less equivalents only. The difficult question is to identify the borders, when and to what extent the differences are so significant that they outweigh the similarities, and the use of the “false-equivalent” would result in misleading the reader and their misunderstanding of the text. If the border is crossed, paraphrasing or even neologism must be preferred.

3 Conclusions

The primary goals of translation of civil codes drafted in internationally less-used languages into a lingua franca (i.e. making their content accessible to academics and practitioners from other legal systems) are manifold. It facilitates mutual understanding regarding the legal background of cross-border business, including but not limited to the choice of those laws under private international law, since people are only scared of those things that they do not know or understand. Having the new Hungarian Civil Code translated increases the chances of obtaining substantive reflection from abroad, i.e. from the international academic community. The closer the respective legal systems are regarding the language and the merits, the easier it is to reproduce a civil code in the target language and to keep the original meaning as much as possible. Another general finding is that the more the target language is neutralised and internationalized (i.e. became detached from the own legal system, whether due to the legal harmonization within the EU or the result of having already drafted international treaties and/or soft laws using the target language as a lingua franca), the easier it is to perform the translation to this language.

The results of the translation project and research reported on in this paper however reveal some deeper and more substantial correlations. They shed light again and again on the embeddedness of the law in the language and vice versa: on the embeddedness of the (legal) terms in the law; in other words, on their interwoven and interdependent cohesion. Separation of the wording from the context of culture and language necessarily results in distortions to a certain extent regarding the meaning and/or to misunderstandings or even not understanding the translated text. The interdependence of law and language might be seen as a barrier as far as the primary goals of translation are concerned; nevertheless, it can serve as a valuable tool for comparatists in fine-tuning their findings.

Whether the use of the closest (functional) equivalent, paraphrasing or creating a neologism is opted for depends generally on the ratio of similarities to differences (hereinafter referred to as SD-ratio or SD-relationship) between the rules and concepts behind the respective terms, which should not be understood in a purely mathematical or numerical sense. It does not necessarily depend on any frequencies either. Whether the similarities outweigh the differences or vice versa depends on many factors, thus the “big picture” matters. The complexity of legal matters and considerations, policies, etc. behind them cannot be shaped using mathematical formulae. A rough guideline is that if the use of the closest functional equivalent results in creating a false friend that misleads the international readership on the content, i.e. if the differences outweigh—if at a structural level in particular—then it is advisable not to cross this red line and to decide to paraphrase or use a neologism. However, the use of a well-known and hardly if ever replaceable term can sometimes still be the least worst solution, despite significant conceptual differences between the contents of the terms in the respective languages and, in the same way, between the respective legal systems (see for example “consideration” above). Having this in mind, the experiences of legal translations can support comparative analyses in at least two aspects. First, they serve as a control mechanism, as a kind of language-oriented double-check of the hypotheses. Second, they channel and catalyse the comparative analyses themselves, since they enforce the evaluation of similarities and differences in statutory law and beyond.

No doubt, using the closest (functional) equivalent indicates that there are more similarities than differences, while paraphrasing and neologisms draw the readers’ attention to the differences, i.e. to the “otherness” of the translated rule(s). In that sense, functional equivalents reveal more on the merits compared to the other two techniques. Legal translation offers the opportunity to create a kind of “checks and balances of legal terminology” in combining several methods if, and as far as, necessary. First, a principal and substantive decision is to be made with regard to the SD-ratio at a structural level, and then the overall picture can be fine-tuned with the other tools. That’s what happened to the Hungarian version of trust, to be more precise: to the fiduciary asset management contract. Due to the overwhelming structural differences between the common law concept of horizontally divided property and the continental European versions of managing property for others, the translator opted—correctly—for paraphrasing, which created a presumption of dissimilarities and warns the readership not to expect the genuine Anglo-Saxon concept of trust from that contract. However, after this clearly accented caution, the original (equivalent) English terms are used with reference to the parties and to their contracting positions (settlor, trustee, beneficiary), which adds a soft and quiet counter of similarity to the big choir and orchestra of differences within the polyphonic harmony of legal translation. The overall picture enables the international reader (with some legal background knowledge) to understand that fiduciary asset management contract is no trust in a common law sense, but, since the contracting parties and their positions are pinpointed by well-known English terms, this type of agreement serves the same goals, but in a civil law-conform manner.

Notes

A translation provided by Iuris GmbH as a service provided by the Federal Ministry of Justice, available at https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bgb/englisch_bgb.pdf.

Act No. SR 210, available at the governmental portal: https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/19070042/201801010000/210.pdf.

Act No. SR 220, available at the governmental portal: https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/19110009/201704010000/220.pdf.

Act V of 2013 on the Civil Code (entered into force on 15th March 2014).

Available at: http://njt.hu/njt.php?translated.

According to Kelsen “The legal norms enacted by the law creating authorities are prescriptive; the rules of law formulated by the science of law are descriptive” [7: 459]. In German he calls a prescriptive sentence a Norm and a descriptive sentence a Rechtssatz.

Title XXXII (Unjustified Enrichment) of Book 6 (Law of Obligations).

See the English translation of the BGB (Sections 812–822, cf. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bgb/), of the ZGB (Arts 62-67, cf. https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/19070042/index.html) or the English version of the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts 2016, p 371. (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/commercial-contracts/unidroit-principles-2016).

Section 6:143 Para 2 HCC: “Other damage to the assets of the obligee and the loss of profit that occurred as a consequence of the breach of contract shall be compensated for to the extent the obligee proves that the damage, as a possible consequence of the breach of contract, was foreseeable at the time of concluding the contract.” (Emphasis added.).

Section 6:521 HCC: “No causal link shall be established in connection with any damage which the person causing it could not foresee and should not have foreseen.” (Emphasis added.).

Available at: https://www.trans-lex.org/400200/_/pecl/.

Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts, Unidroit, 2016, Rome. Available at: https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/commercial-contracts/unidroit-principles-2016.

Principles, Definitions and Model Rules of European Private Law, Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR), outline edition, Sellier, 2009. Available at: https://www.law.kuleuven.be/personal/mstorme/european-private-law_en.pdf.

See DCFR IIII-2.103, PECL 7:103.

See DCFR II-4:208, PECL 2:208, Unidroit Principles 2.1.11.

See the English translation of the BGB (Sections 677–687: Agency without specific authorisation) or the OR (Arts 419-424: Agency without authority).

See the Comments on VI-6:101 DCFR, p. 3559.

See DCFR I-1:03, PECL 1:102.

Section 631 of the BGB.

Section 6:238 of the HCC provides that “Under a contract to produce a work, the contractor shall create a result (hereinafter “work”) by performing certain activities, and the client shall accept it and pay the contractor’s fee.”.

See for before all Section 316 of the BGB on the specification of consideration (Bestimmung der Gegenleistung).

The leading case providing a definition is Currie v Misa (1875) LR 10 Ex 153; (1875-76) LR 1 App Cas 554: “A valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either in some right, interest, profit, or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility, given, suffered, or undertaken by the other.”

See for example Arts 9, 81, 184 B, 195a G, 337 B, etc. ZGB.

In UK law, public deed has a much a narrower meaning than it does have in civil law systems. This can be explained by the fact that civil law type “notarial deeds” do not exist in the common law countries, where the function of public notaries is limited to ascertaining the identity of the person signing a document or taking that person’s sworn statement [26].

See also the semi-official English language version of the Spanish Civil Code at http://derechocivil-ugr.es/attachments/article/45/spanish-civil-code.pdf (Arts 103, 198, 317, 540, 541, 633, 703, etc.).

Book II (Contracts and other juridical acts), Article I:101 (2).

Section 6:4 paragraph (4) of the HCC foresees an explicit reservation concerning silence or abstention from a certain conduct, which shall only qualify as a juridical act if the parties expressly provided so. No similar express reservation is to be found in the DCFR. That minor difference does not however question the equivalence of the two concepts as far as their essential characteristics are concerned.

See the definition of “Person” in the Annex to the DCFR or I-1:105, IV-3:201 (2), X-5:204 (2). Legal person has become a commonly used term of EU law as well.

In the DCFR, see under page 63 (Protection of a person) a person’s right to physical wellbeing and the right of dignity are mentioned among personality rights. Personality rights are furthermore enumerated in the definition list of Rights as a right to respect for dignity, or a right to liberty and privacy. On the origin of the concept of right of privacy and personality rights see [28].

Section 7:67 [Lineal property]

-

(1)

If the intestate heir is not a descendant of the testator, the assets passed to the testator from one of his ascendants through succession or gifting shall be subject to lineal inheritance.

-

(2)

Lineal inheritance shall apply to assets inherited or gifted from a sibling or a descendant of a sibling if the asset was inherited by or gifted to the sibling or the descendant of the sibling from an ascendant he shared with the testator.

-

(3)

The person who would inherit the asset under this title shall prove that the asset is subject to lineal inheritance.

-

(1)

Section 2:42 [General protection of personality rights]

-

(1)

Everyone shall have the right, subject to limitations by law and by the rights of others, to exercise his personality rights freely, in particular the right to respect for his private and family life, his home, and to his communications made by whatever ways or means, and the right to good reputation and not to be hindered by anyone from exercising these rights.

-

(2)

Everyone shall respect human dignity and the personality rights derived from it. Personality rights are protected by this Act.

-

(3)

A conduct to which the person concerned has given his consent shall not violate personality rights.

-

(1)

Section 2:43 [Specific personality rights] Violation of personality rights means in particular

-

a)

harm to life, physical integrity and health;

-

b)

violation of personal liberty and privacy, and trespass;

-

c)

discrimination against a person;

-

d)

defamation or violation of good reputation;

-

e)

violation of the right to keep personal secrets and the right to the protection of personal data;

-

f)

violation of the right to a name;

-

g)

violation of the right to the protection of one’s image and recorded voice.

-

a)

This seems to be contradictory to some extent with the wording of Section 2:52 Para 1 HCC, according to which non-material harm must have been caused to the victim: “Any person whose personality rights have been violated may claim a grievance award for non-material harm done to him.” The Advisory Council on the New Civil Code besides the Curia (i.e. the highest court in Hungary) is of the view that no grievance award shall be awarded in the absence of any perceptible non-material harm, cf. the published opinion of the Advisory Body: https://kuria-birosag.hu/hu/ptk?tid%5B%5D=344&body_value=.

Smart-money is used as an equivalent in the English-German, German-English Dictionary of Law and Business Terminology published in 1929 by v. Beseler [30].

“Wer jemanden an seinem Körper verletzet, bestreitet die Heilungskosten des Verletzten; ersetzet ihm den entgangenen, oder wenn der Beschädigte zum Erwerb unfähig wird, auch den künftig entgehenden Verdienst und bezahlt ihm auf Verlangen überdieß ein den erhobenen Umständen angemessenes Schmerzengeld.” Section 1328 contains a similar provision on (the infringement of) sexual self-determination, but the legislator does not use the word Schmerzengeld there (but that of “angemessene Entschädigung”, i.e. “reasonable compensation”).

It should however be noted that the term “business association” is not a completely artificial one. In some common law countries (mainly in the US and in Africa [41]) it is used as a general term to cover all forms of business-like activities in a very broad sense without referring to or willing to encompass specific types of business forms. On the other hand, the Hungarian term “gazdasági társaság” is specific and precise in being a cover term for four well-identified types of legal entities pursuing business activities.

See the Company Act 2006, the Partnership Act 1890 and the Limited Liability Partnership Act 2000.

See Part III (Companies) of Book 3 (Legal Persons) of the HCC.

References

Curran, Vivien Grosswald. 2019. Comparative Law and Language. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Law, ed. Mathias Reimann and Reinhard Zimmermann, 681–708. Oxford: OUP.

Gémar, Jean-Claude. 2006. What Legal Translation is and is not – Within or Outside the EU. In Pozzo, Barabara and Jacometti, Valentina (eds.) Multilingualism and the Harmonisation of European Law. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International 69–77.

Harvey, Malcolm. 2002. What’s so Special about Legal Translation? Meta: Translators’ Journal. Vol. 47. No. 2. 177–185.

De Groot, Géraud-René. 2002. Rechtsvergleichung als Kerntätigkeit bei der Übersetzung juristischer Terminologie. In Sprache und Recht, ed. Ulrike Hass-Zumkehr, 222–239. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Šarčević, Susana. 1997. New Approach to Legal Translation. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Fischer, Márta. 2010. A fordító, mint terminológus, különös tekintettel az európai uniós kontextusra. Thesis. ELTE BTK

Kelsen, Hans. 2009. General Theory of Law and State. New Brunwsick, London: Transaction Publishers.

Bednárova-Gibov, Klaudia. 2014. EU Discourse as a Textual, Legal and Linguistic Challenge. Filológia 1–4: 4–17.

Cao, Deborah. 2007. Translating Law. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Matulewska, Aleksandra. 2017. Contrastive Parametric Study of Legal Terminology in Polish and English. Contact: Studies in Legal Language and Communication. Poznan.

Jansen, Nils. 2016. Farewell to Unjustified Enrichment? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2740322, available also in The Edinburgh Law Review 20.2 (2016): 123-148.

Menyhárd, Attila. 2014. Unjustified Enrichment in the New Hungarian Civil Code. ELTE Law Journal 2: 233–245.

Dannemann, Gerhard. 2009. The German Law of Unjustified Enrichment and Restitution. Oxford: OUP.

Giglio, Francesco. 2003. A Systematic Approach to ’Unjust’ or ’Unjustified’ Enrichment. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 3: 455–482.

Fuglinszky, Ádám. 2015. The Reform of Contractual Liability in the New Hungarian Civil Code: Strict Liability and Foreseeability Clauses as Legal Transplants. Rabels Zeitschrift für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, (79) No. 1, 72-116.

Beale, H.G. 2012. Chitty on Contracts. 31st ed. London: Sweet & Maxwell.

Csöndes, Mónika. 2014. A szerződésszegési jog előreláthatósági korlátjának joggazdaságtani modellje és annak kritikája. Állam- és Jogtudomány 1: 3–35.

Cowan, Rosaline Baindu. 2013. The Effect of Transplanting Legislation from one Jurisdiction to Another. Commonwealth Law Bulletin. 39(3): 479–485.

Goddard, Christopher. 2009. Where Legal Cultures Meet: Translating Confrontation into Coexistence. Investigationes Linguisticae XVII: 168–205.

Beale, H.G., W. Bishop, and M.P. Furmston. 2008. Contract Cases and Materials. 5th ed. Oxford: OUP.

Mckendrick, Ewan. 2009. Contract Law. 8th ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chen-Wishart, Mindy. 2013. In Defence of Consideration. Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 13(1): 209–238.

Furmston, M.P. 2007. Cheshire, Fifoot and Furmston’s Law of Contract. 15th ed. Oxford: OUP.

Cartwright, John. 2007. An Introduction to the English Law of Contract for the Civil Lawyer. Oxford and Portland: Hart.

Atiyah, P.S. 1986 (reprinted in 2001). Essays on Contract. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Rossini, Christine. 1998. English as a Legal Language. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Sándor, István. 2016. Different Types of Trust from an Ownership Aspect. European Review of Private Law 6: 1189–1216.

Strömholm, Stig. 1967. Rights of Privacy and Rights of the Personality. Stockholm: Instituti Upsaliensis Iurisprudentiae Comparativae.

Homoki-Nagy, Mária. 2000. A törvényes öröklés jogi szabályozása 1861-ig. Acta Universitatis Szegediensis: Acta juridica et politica. 52: 212–230.

von Beseler, Dora. 1929. English-German, German-English Dictionary of Law and Business Terminology. Berlin, Leipzig: de Gruyter.

Oetker, Hartmut. 2019. § 253 BGB. In Münchener Kommentar zum BGB (8 ed. – online version; references pinpoint marginal numbers).

Rixecker, Roland. 2019. Anhang zu § 12 BGB. In Münchener Kommentar zum BGB (8 ed. – online version; references pinpoint to marginal numbers).

Van Dam, Clees. 2013. European Tort Law. Oxford: OUP.

Markesinis, Basil, Michael Coester, Guido Alpa, and Augustus Ullstein. 2005. Compensation for Personal Injury in English, German and Italian Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spindler. 2019. § 253. In Beck Online Kommentar – Bamberger/Roth/Hau/Poseck (51 ed. – online version Stand 01. 08. 2019.).

Danzl. 2017. § 1325 ABGB. In Koziol, Bydlinski, and Bollenberger (eds.) ABGB Kurzkommentar. 5 ed. Wien: Verlag Österreich - references pinpoint marginal numbers.

Harrer-Wagner. 2016. § 1325 ABGB. In Schwimann and Kodek (eds.) ABGB Praxiskommentar Band 6 . 4 ed. Online Version – Stand März 2016 - references pinpoint marginal numbers.

Hinteregger. 2018. § 1325 ABGB. In Kletečka/Schauer ABGB Online Kommentar – Version 1.04 (Stand 1. 4. 2018, drb.at - references pinpoint marginal numbers).

Huber. 2017. § 1325 ABGB. In Schwimann and Neumayr (eds.) ABGB Taschenkommentar (4 ed.). Online Version, Stand Oktober 2017 references pinpoint marginal numbers.

Karapanou, Vaia. 2014. Towards a Better Assessment of Pain and Suffering Damages for Personal Injuries. A Proposal Based on Quality Adjusted Life Years. Cambridge: Intersentia.

Chungu, Chanda. 2019. The Law of Business Associations in Zambia. Cape Town: Juta.

Morse, Geoffry. 2010. Partnership Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper is intended to be part of the Special Issue “Hungarian Language and Law: Developing a Grammar for Social Inclusion, a Vocabulary for Political Emancipation” guest edited by Máté Paksy and Edina Vinnai.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fuglinszky, Á., Somssich, R. Language-bound terms—term-bound languages: the difficulties of translating a national civil code into a lingua franca. Int J Semiot Law 33, 749–770 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09704-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09704-x