Abstract

Tender Shoots is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) for parents aimed at improving preschool children’s oral language skills relevant for later reading. Parents of 72 preschool children (M = 50 months) were randomly assigned to either a Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR) condition, a Strengthening Sound Sensitivity (SSS) condition, or an Activity-Based Control (ABC) condition. RRR and SSS conditions involved dyads conversing about the same 12 books over 6 weeks, with RRR focused on the meaning of the story in relation to children’s own experiences, and SSS focused on soundplay. Children’s oral narrative skills were assessed with a story listening comprehension and retelling task before and one-year post-intervention. At the 1-year follow-up, children in RRR retold stories with greater accuracy (g = 0.61) and quality (g = 0.68) than did children in the control condition. Tender Shoots RRR is a promising tool for parents to help their children’s narrative production (retelling) skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Young children’s narrative skills are an important aspect of their oral language development, integrating lexical, syntactic, microstructure, macrostructure, and pragmatic dimensions (e.g., Justice et al., 2010). By the preschool years, children’s facility with understanding and producing oral narratives is growing rapidly. For example, 3- and 4-year old children are able to understand basic storylines and to retell a story they have just heard, especially if in the context of a picturebook (Justice et al., 2010). Young children’s oral narrative skills contribute uniquely to their school readiness and reading skills (e.g., Gardner-Neblett & Iruka, 2015; Reese, Suggate, Schaughency, & Long, 2010; Schaughency, Suggate, & Reese, 2017). Thus, children’s oral narrative skills are key for their later reading and success in school.

What are the sources of influence on children’s oral narrative skills? A large body of research now shows that parents can foster children’s oral narrative development through co-constructing stories about past experiences together, or reminiscing (see Salmon & Reese, 2016 for a review; Waters et al., 2019 for a meta-analysis). In contrast, much less is known about how to foster children’s oral narrative skills through other conversations, with interactive book-reading a particular context of interest (see Spencer & Petersen, 2013; Veneziano & Nicolopoulou, 2019; Zevenbergen et al., 2003). The present study reports on a parent-led picturebook-based RCT called Tender Shoots: Rich Reading and Reminiscing that included interactive book-reading combined with post-reading reminiscing activities to help parents foster their preschool children’s oral language skills (see Riordan et al., 2021 for early literacy skills at post-test and Schaughency et al., 2022 for beginning reading outcomes). The focus of the current paper is on long-term narrative outcomes of Tender Shoots. Specifically, we investigated changes in children’s story comprehension and production (retelling) across conditions one year after the intervention had ended.

Adult–Child picturebook reading and children’s oral language skills

Drawing upon 50 years of research, it is now abundantly clear that shared picturebook reading between parents and children can boost children’s oral language skills (for meta-analyses, see Dowdall et al., 2020; Flack et al., 2018; for reviews see Reese, 2019; Wasik et al., 2016). In particular, a challenging, high-level interactive style with older preschoolers in which parents focus on inferences about the storyline is positively associated with children’s oral language skills, both concurrently and over time (e.g., Haden et al., 1996; Hindman et al., 2008; Robertson & Reese, 2017; van Kleeck et al., 1997). This style appears to help children understand causal connections in the storyline.

Experimental research confirms that different styles of book-reading have different effects on children’s oral language. This body of research dates back to dialogic reading, a highly interactive style of sharing a book in which adults ask questions and encourage children’s participation on every page (e.g., Whitehurst et al., 1988). When middle-class parents of two-year-olds were taught to read dialogically, their children grew faster in their expressive vocabulary and syntax than children whose parents read in their typical fashion. A version of dialogic reading for older preschoolers consists of a suggested sequence of prompts for each page (Prompt-Evaluate-Expand-Repeat or PEER) that vary in their content and structure (Completion-Recall-Open Ended-Wh-Distancing or CROWD; see Whitehurst et al., 1994). Note that only the Distancing prompts (links to child’s own life) and sometimes the Wh-prompts of dialogic reading (What, Who, When, Why) would be considered high-level comments. When parents and teachers are taught to read dialogically, preschool children benefit primarily in terms of their expressive vocabulary (see meta-analyses by Mol et al., 2008, 2009; see also Şimşek & Erdoğan, 2021), but benefits are moderated at times by the age of the children and by the dosage of dialogic reading received. Younger children and those whose teachers were more faithful in delivering dialogic reading benefited most in their expressive language.

Dialogic reading also helps children’s expressive narrative development. For instance, in a combined program in which low-income children’s teachers and parents read dialogically over the preschool year, children in the dialogic reading groups used more evaluative devices (internal state talk and dialogue) in their story retellings at the end of the year in a standardized story retell measure (Zevenbergen et al., 2003). Moreover, in a narrative-enriched dialogic reading study, researchers asked questions about picturebooks’ plot, theme, and evaluative elements of the storyline with small groups of 5- to 6-year-old children over 8 weeks. At an immediate post-test employing different picturebooks, children in the dialogic reading group retold narratives that included more story elements, and specifically more internal states, compared to children in an alternative phoneme-awareness treatment group (Lever & Sénéchal, 2011).

However, most dialogic reading studies are with early childhood teachers, not parents. Pesco and Gagné (2017) conducted a meta-analysis of three decades of interactive book-reading studies with teachers that included narrative outcomes. They reviewed only high-quality experimental studies that included an alternative reading condition, excluding studies with only a no-treatment control condition. Their main finding was that interactive book-reading in the classroom (which they termed verbal scaffolding) had moderate benefits for children’s narrative comprehension and expression skills. These benefits were stronger when the program included a nonverbal component, such as props or post-reading activities encouraging children to act out the story.

The body of research on parents’ facilitation of children’s narrative skills through book-reading is much more limited. For instance, Harkins (1994) found that children used more evaluative devices in their independent story retellings of a wordless picturebook when their mothers had previously used a wide range of evaluative devices in dyadic storytelling. Other correlational studies since have demonstrated that mothers’ high-level inferential utterances and open-ended questions during book-reading are positively linked to preschool children’s independent story retelling (Kang et al., 2009; Reese, 1995).

Even fewer experimental book-reading studies with parents have included narrative outcomes. For instance, Aram and colleagues (Aram et al., 2013; Fine et al., 2019) taught one group of low-SES Israeli parents to talk more during shared book-reading about the plot of the story, mental states, related personal experiences, and to encourage children’s retelling of the story. Parents and children in a control group received the same books and number of home visits, but were not taught any specific strategies. At a short-term post-test, children in the experimental group told longer and better sequenced story retells of the post-test book to a researcher, and included more mental state terms, than did children in the control group. These findings are impressive given that parents of children in the control group read the same books the same number of times as parents of children in the experimental group, indicating that hearing the text alone is not enough to help children’s narrative development over a short timeframe. Taken together, these studies all show that children’s narrative skills prosper when adults extend book talk beyond the text to explore the storyline, talk about mental states, and link the story to the child’s own life.

Adult–Child reminiscing and children’s oral narrative skills

Although picturebook reading with both teachers and parents appears to be an excellent context for promoting children’s oral narrative skills, it is not the only way. Parenting interventions that encourage open-ended questions and responsive turn-taking during everyday conversations across a number of contexts also facilitate children’s oral language skills (e.g., Landry et al., 2012; see Hoff, 2006 for a review). For instance, parents and children in a diverse range of cultures reminisce about their memories of personal experiences (see Miller et al., 1990), and these memory conversations increase in frequency over the early childhood period (Rowe, 2012). Memory conversations are initiated by both parents and children (Reese, 1999), and occur on average over 5 times an hour in middle-class Western families with preschool children (Mullen & Yi, 1995). The resulting conversations can be brief or extensive, with wide individual differences within cultures in the degree to which parents elaborate by providing more details about the memory and confirm and follow-in on their children’s responses (called “elaborative reminiscing”; see Fivush et al., 2006; Salmon & Reese, 2016; Wang, 2001). Across cultures, parents who are more elaborative and confirming in their reminiscing have young children with advanced vocabulary and oral narrative skills (see Fivush et al., 2006); in a meta-analysis of over 900 mother–child dyads, mothers’ elaborative reminiscing was also positively linked to preschool children’s language on standardized vocabulary tests (Waters et al., 2019).

The reminiscing interventions conducted to date are almost all with parents (but see Schröder et al., 2019 for a successful quasi-experimental reminiscing intervention with early childhood teachers). These experimental studies confirm that teaching mothers to reminisce elaboratively leads to children producing more advanced personal narratives years after the coaching sessions have finished (Mitchell & Reese, 2022; Peterson et al., 1999; Reese & Newcombe, 2007; Reese et al., 2020). In one study with low-income families whose children were attending Head Start, children of mothers who had been taught elaborative reminiscing techniques were more advanced in their narrative skills in a story retelling task 6 months later compared to children of mothers who had been taught dialogic reading techniques (Reese et al., 2010a, b). Reese (2012) argued that reminiscing may pose a complementary or even alternative context for intervention with low-income parents who do not regularly read picturebooks with their young children (e.g., Raikes et al., 2006).

Weaving together reading and reminiscing: the present study

The aim of the present study was to unite these two powerful contexts — shared book-reading and elaborative reminiscing — for boosting children’s oral narrative skills into a single program called Tender Shoots: Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR). The current version is designed for parents, with another version being trialled with early childhood teachers (Clifford et al., 2022a). Because the features of shared reading and reminiscing that appear to foster children’s oral narratives are similar across the two storytelling contexts — open-ended questions containing high-level information; praise and responsive turn-taking — we predicted that their combined power might be even more effective for children’s narrative skills (see Riordan et al., 2021 for immediate effects of a soundplay version of Tender Shoots called Strengthening Sound Sensitivity (SSS) on preschool phonological awareness and letter recognition; and Schaughency et al., 2022 for longer-term effects of SSS on beginning word-reading in primary school). Moreover, Hindman et al. (2014) noted that the main book-reading strategy driving the positive link to children’s oral language in their large sample was parents’ references to children’s real-world experiences – in other words, reminiscing. Although other book-reading interventions have encouraged adults to draw connections to the child’s own life during the reading (e.g., Fine et al., 2019; Zevenbergen et al., 2003), no other program besides RRR has incorporated in-depth, stand-alone reminiscing conversations linked to story themes after the reading has been completed. Based on knowledge of the strong effects of post-event conversations on autobiographical memory (see Reese, 2018), combined with the power of post-reading activities for children’s oral language (Baker et al., 2020), we argue that these post-reading reminiscing conversations will result in stronger oral narrative advantages for children.

Thus, our program Tender Shoots: Rich Reading and Reminiscing draws upon all of the features of interactive reading and reminiscing that past research has identified as beneficial for children’s oral language development: repeated readings, scaffolded comments and open-ended elaborative questions of increasing demand levels, and praise and expansion of children’s utterances. We also drew upon our own correlational and experimental research on these conversational strategies with New Zealand children (Farrant & Reese, 2000; Reese, 2013; Reese & Cox, 1999; Reese & Newcombe, 2007; Reese et al., 2015). Families were randomly assigned to the target treatment condition, Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR), or to an alternative shared book-reading treatment condition, called Strengthening Sound Sensitivity (SSS), or to an activity-based control group (ABC).

Families in both of the book-reading conditions received the same 12 books over 6 weeks, 2 books each week. Books in both conditions contained embedded prompts of increasing demand over three successive readings and suggestions for post-reading activities linked to extra-textual interactions during the story, but the content of prompts within each book and suggested follow-up interactions differed across conditions (see Table 1). Families in the target RRR condition were instructed to comment and ask questions about the storyline and to define new words and emotions for children, with the demand level growing over repeated readings. In RRR, each reading of a book was followed by a suggested reminiscing conversation that built on a theme of the story (e.g., talking about a time parent and child baked together after reading The Gingerbread Man, Kimmel & Lloyd, 1993). Families in the alternative treatment condition of SSS were instructed instead to draw attention to sounds within words during the interactive reading, and to engage in follow-up singing or soundplay activities building on phonological concepts introduced during the reading (e.g., singing Old MacDonald about animals that rhyme or start with the same sound). Families in the ABC condition received new materials each week for 6 weeks of structured play activities focusing on art, movement, healthy choices, self-care, music, and science themes.

Previous findings from Tender Shoots at immediate post-test show that parents and children who participated in RRR displayed higher levels of meaning-focused talk during book-reading and reminiscing, and those in SSS more sound-focused talk during book-reading (Riordan et al., 2021) and that these changes endured at the one-year follow-up (Clifford et al., 2022a, 2022b; Timperley et al., 2022). Moreover, condition-related interaction variables were linked to children’s outcomes at the immediate post-test. For example, RRR techniques such as parents’ mental state talk during book-reading and their elaborations during reminiscing were both positively associated with children’s story comprehension at post-test (Das, 2018), although there were no reliable main effects of condition for children’s story comprehension at immediate post-test. Also, older preschool children who participated in SSS displayed higher levels of phonological awareness and letter recognition (Authors, 2021).

The present focus is on longer-term effects of the parent version of Tender Shoots (specifically RRR) on children’s story comprehension and retelling at a one-year follow-up, after children entered primary school and began formal reading instruction. This is an important timepoint for evaluating these listening comprehension skills for several reasons. First, promising effects of early intervention during preschool can fade out (Mashburn et al., 2018); therefore, evaluation of potential benefits following the transition to school is needed (Lonigan & Shanahan, 2010). Second, although Tender Shoots has documented longer-term benefits for decoding-related skills in beginning reading (Schaughency et al., 2022), evaluations to date have not included oral narrative skills. In the early school years, children’s performance on reading comprehension measures depends heavily on their word-level reading skills; therefore, assessing oral language comprehension outside of reading has been recommended to tap comprehension processes during this window (Lonigan & Burgess, 2017). Finally, some parent–child reminiscing interventions have shown sleeper effects on children’s oral language skills, such that the effects 6–12 months post-intervention are stronger than at immediate post-test, presumably because parents continued to use the new techniques (Peterson et al., 1999; Reese et al., 2010a, b). Moreover, in book-reading intervention studies with parents, the dose of the intervention affects the strength of the benefits for children’s oral language (Dowdall et al., 2020). These findings led to two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

That RRR would result in specific benefits for children’s story comprehension and retelling after one year compared to soundplay-based book-reading (SSS) and to the no-reading control group (ABC).

Hypothesis 2

That implementation might moderate benefits of RRR for children’s oral narrative skills..

Method

Participants

We recruited 72 families with 3–1/2 to 5-year-old children attending one of eight early childhood centres in a small city in New Zealand (NZ). Most children in New Zealand begin primary school on their fifth birthday, so we wanted to recruit children who would be attending early childhood education throughout the intervention phase. On average, children were 4 years old (M = 50.24 months; SD = 3.96) at pretest; all but one parent reported speaking English as a first language in the home, with one parent reported to speak English and Arabic equally. Four parents also reported speaking a second language besides English in the home (Māori, German, or Chinese). The early childhood centres were selected because they serve families with diverse backgrounds; participating parents ranged widely in their highest educational qualification (3% intermediate; 24% high school; 28% trade certificate or polytechnic degree; 29% bachelor’s degree; 16% postgraduate degree). Families also ranged in their household socioeconomic status (from unemployed and low SES to the highest level of SES based on the NZSEI-06; Milne et al., 2013), with 68% coming from a mid- to high-SES household. We invited the parent who read most often with the child as the primary participant (n = 70 mothers and 2 fathers). Using the total response method (Statistics New Zealand, 2005), in which parents can nominate multiple ethnicities, 96% of the participating parents identified as NZ European and 15% as NZ Māori. Other ethnicities parents reported, each less than 5%, were Pacific Island, Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and other European. At pre-test on a daily checklist for seven days, parents reported engaging in shared book-reading on 5.9 days a week on average and in reminiscing on 6.2 days a week on average; all parents reported sharing books at least once a week and reminiscing at least twice a week (see Riordan et al., 2021). Thus, at the outset of the study, all parents were already reading and reminiscing with their children, making these practices an ideal target for intervention.

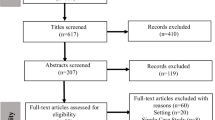

Three dyads discontinued their participation after pre-test and group assignment, but before implementation (N = 69). Two additional dyads withdrew from the study after the immediate post-test (N = 67). At the 1-year follow-up, two families had moved to another town, and an additional three families withdrew from the study (so N = 62 or 90% of families who participated in the intervention phase; see Fig. 1 for a flow chart). At the 1-year follow-up, children ranged in age from 61 to 75 months (M = 65.33 months; SD = 3.47); all attended a primary school.

Note. At one-year follow up, all children were in their first year of primary school. Reasons for loss to follow-up include moving away from the area.

Procedure

After completing consent forms, parents completed a demographic questionnaire at home. Then a team of trained postgraduate researchers individually assessed children’s skills in two 30-min sessions typically conducted in a quiet room in the early childhood centre at pre-test, and in a quiet room in the child’s primary school classroom at the 1-year follow-up, with a few families opting to be seen at home or at a university family study lab. All assessors were blind to children’s condition assignment. Children’s oral narrative skills were assessed in a story comprehension and retelling task using a different age-appropriate book near the end of the second session at each timepoint. This placement was to ensure that children were more familiar with the researcher when we administered the narrative production tasks. The story retelling task was later coded separately for children’s memory for the story as well as the quality of their stories, in line with prior research showing that these two dimensions are both important but differential predictors of children’s later reading skills (Reese et al., 2010a; Reese et al., 2010b).

Story comprehension

To standardize the story exposure, the researcher played a digital recording of another researcher reading a story (Peter’s Chair by Ezra Jack Keats at pretest; Frog, Where Are You? by Mercer Mayer at the 1-year follow-up) while the researcher and child looked at the book together and turned the page when indicated. These books were chosen because they have been used in previous research with these age groups (Reese et al., 2010a, 2010b; Berman & Slobin, 1994), and because they would be unfamiliar to the children. Both had a strong narrative storyline. A wordless picturebook was chosen for the final timepoint because children had entered primary school and had begun reading instruction; the text of the story was taken from Westerveld and Vidler (2014). Immediately after each reading, the researcher asked 6 comprehension questions assessing children’s recall of key story elements common across the two books, such as characters, important story events, and inferences about characters’ intentions and emotions (see Appendix A). Children’s answers were audiotaped and later transcribed and scored for accuracy, with one point given for each correct question for a possible total of 6 at each timepoint. Two independent coders who were blind to children’s condition achieved reliability on 25% of the transcripts of 98% at pre-test and 88% at 1-year follow-up.

Story retelling

After the audio recording and the story comprehension questions, the researcher brought out a penguin puppet, introduced as Paddles. The researcher said that Paddles had been sleeping in her bag and had not heard the story, and asked the child to tell the story to Paddles. The researcher initially prompted with “Here, I can help you start. It’s called _______(book title).” and then turned the pages of the book, praising children’s responses in Paddles’ voice and encouraging them to tell more of the story until the child stopped responding or indicated the story was finished (see Appendix B for an example). Assessors were trained to use a standard set of prompts with a maximum of 2 “empty” prompts per page (e.g., “Oohhh,” “Mmm,” and “Tell me more”).

Children’s retellings were first transcribed and then coded for story memory and quality using an established scheme (Reese et al., 2010a, b). For story memory, each child utterance was compared to the text of the story. Children received 1 point for correctly recalling the gist of a proposition from the text for a possible total of 41 propositions at pre-test and 50 propositions at 1-year follow-up. Story memory units were summed for a total story memory score at each timepoint (41 at pre-test and 50 at follow-up to correspond to text propositions).

Each unit of story memory was subsequently coded for six subtypes of story quality, with 1 point given for each instance of quality: character introduction (Peter, Mum); evaluations (internal state: she was sad; descriptive: she was pretty; intensifier: it was way too small; repetition for emphasis: it was too too small); temporal (At the beginning; that’s the end); causal (because it was too small); dialogue (He called, “Frog, where are you?” or using voices for different characters); verbatim (reproduction of a proposition with near-perfect accuracy). Quality subtypes at post-test were summed for a total story quality score. Each proposition recalled could hypothetically receive a maximum of 6 points for the different quality subcategories.

The same two coders, both blind to children’s condition, independently coded 25% of the story retellings at each timepoint for reliability. At pre-test, reliability for story memory was 95.61%; story quality coding was not conducted because there were so few instances. At the one-year follow-up, reliability for story memory was 85% and for story quality was K = 0.97.

Intervention phase

Dyads were randomly assigned to a condition within early childhood centres. A parent education session of equal length and parallel structure took place in small groups at the early childhood centre or individual sessions at home as needed for both of the book-reading conditions (RRR and SSS). In both conditions, a researcher began by presenting slides on a laptop computer that first outlined why the skills targeted were important for children’s development. Then the researcher modelled methods for encouraging children’s active participation in project activities through contingent and responsive replies with an assistant in which parents were taught to confirm children’s utterances and expand upon them (called “echo and add”). Parents were encouraged to pause for at least two seconds after asking a question, and to scaffold children’s answers by giving “just enough help.” The researcher then taught parents the specific techniques for each condition targeted in each reading and post-book interaction (Table 1).

Of particular interest for these analyses, in RRR, we encouraged parents to select and discuss one-time events that they thought their children could remember for reminiscing conversations (adapted from Reese & Newcombe, 2007). Parents were taught to ask open-ended elaborative questions about the event, including about children’s emotions (“What part of the picnic did you like best?”), and to confirm children’s responses (“That’s right, good memory!”). For both positive and negative events, parents were encouraged to validate children’s emotions and perspectives. We told parents in both book-reading conditions that post-reading interactions could be done anytime – for example, reminiscing about related past events in the car on the way to childcare, or at a mealtime – instead of restricting these activities to just after reading the book.

As a resource-only control, parents in the ABC condition did not attend an education session. Parents in all three conditions then received their first week of materials in an A4 cardboard box painted gold and decorated as a treasure box with glitter and plastic gemstones labelled with the child’s name. Each week for the next 6 weeks, researchers delivered books and materials to children’s early childhood centre so that all families received 2 new books each week if they were in a book-reading condition, or new materials for activities if they were in the ABC condition. The books were all commercially available and comprised a mix of classic tales (e.g., The Gingerbread Man by Eric Kimmel), New Zealand books (e.g., Louie the Tui by Janet Martin), and new books (e.g., Jumblebum by Chae Strathie). All were narrative books with a clear storyline; 6 of the 12 books were rhyming books or had rhyming features (see Riordan et al., 2021 for a complete list of books). Books were also selected to have engaging illustrations and not too much text per page to facilitate interactions. Each book contained a total of 33 colour-coded prompts typed on adhesive labels, 10 per reading plus 3 post-reading conversations, tailored to each condition. A researcher phoned parents midway through the program at 3 weeks to answer any questions, remind the parent of key strategies, and to problem-solve if parents were experiencing difficulties. We reminded parents in shared reading conditions at this time that suggested post-reading activities (e.g., reminiscing conversations for RRR) could occur anytime during the week.

Implementation check

Each week along with the new books or materials, researchers delivered an accompanying stamp chart. The stamp chart contained a circle for the dyad to stamp each time they read one of the target books or had one of the target conversations or completed one of the activities. We asked parents to return the stamp charts each week so that we had a record of how many of the assigned activities they had completed in that week. We then computed the proportion of assigned activities completed in each condition as an implementation variable.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Two parents were missing education information because they did not fill out the pre-test demographic questionnaire, so the modal education score was substituted. At pre-test, one child did not engage in the story retelling task. At the 1-year post-test, one child in SSS did not engage in the story comprehension task, and one child in RRR did not engage in the story retelling task. Mean group scores were substituted for analyses.

We were unable to code story quality at pre-test due to floor effects; therefore, at pretest we focus only on story comprehension and story memory. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics on oral narrative variables over time as a function of condition. Implementation was high across conditions, with means of 89% of reading and post-reading conversations completed for RRR, 72% of reading and post-reading conversations for SSS, and 87% of activities for ABC. Although there was a trend as a function of condition (F(2, 66) = 2.88, p = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.08), post-hoc Bonferroni tests did not reveal significant differences between conditions.

Comprehension questions were scored out of 6; story memory scores had a maximum of 41 propositions at pre-test and 50 at post-test; story quality scores had a maximum of 6 quality types (e.g., characters, dialogue, etc.) for each proposition recalled.

Main analyses

We tested our main hypothesis of RRR benefits for oral narrative with analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) using bootstrapping with 1000 iterations and planned contrasts comparing RRR to both SSS and ABC (Field, 2018). We checked descriptives and assumptions prior to conducting these analyses. All variables were normally distributed, all within ranges recommended for parametric statistics (skew < 3.00, kurtosis < 10, Kline, 2011). Story quality sub-types of characters and dialogue were included in analyses but other quality sub-types were too low in frequency (M < 1) to analyze separately (see Table 2).

In line with prior research (see Dowdall et al., 2020), we considered parental education, child age and gender, and pre-test performance as potential covariates. Similar to the results of a meta-analysis of parent-led book-reading interventions (Dowdall et al., 2020), neither parental education nor child age were correlated with any child follow-up measure (rs from -0.11 to 0.10, n.s.) so were not considered further. Child gender was marginally associated with children’s story retelling, with weak to moderate effect sizes favoring girls (see Table 3). Pre-test performance was also marginally associated with follow-up measures (see Table 4). To be conservative, we used children’s pre-test performance as a covariate for story comprehension outcomes, and child gender and pre-test performance as covariates for story retelling outcomes (memory and quality).

To test for independence of the treatment variable and covariates, groups were compared on parental education, child age and gender, and pre-test performance using unpaired t-tests. Results indicated a significant difference between RRR and ABC on pre-test story comprehension, t(44) = 2.38, p = .02. Children in RRR had higher story comprehension scores at pre-test than children in ABC. Therefore, we added pre-test story comprehension as a covariate to all models. For the main analyses, because our sample was small and power was limited, we used bootstrapped planned contrasts with bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals as well as p < 0.05 to interpret results (Field, 2018). When analyses suggested between-group differences, Hedge’s g was calculated as an indicator of effect size.

Results of the overall ANCOVAs are shown in Table 5; results of the planned contrasts comparing RRR to SSS and ABC on follow-up story comprehension and retelling skills are shown in Table 6. Note that we did not necessarily expect significant main effects across conditions because we had hypothesized there would be no advantage of the SSS reading condition over the ABC control for these narrative measures; simply reading the book without discussing the storyline does not appear to help preschool children’s oral language skills (see Pesco & Gagné, 2017; Şimşek & Erdoğan, 2021). Therefore, we interpret the planned contrasts instead in Table 6. For children’s story comprehension, there was no significant benefit of RRR compared to either SSS or ABC. For children’s story memory, there was a significant benefit of RRR compared to ABC but not to SSS. For children’s story quality, there was a marginally significant benefit of RRR compared to ABC but not to SSS. A follow-up analysis of the two most frequent components of story quality, character introduction and dialogue, showed a significant benefit of RRR compared to ABC but not to SSS for dialogue only.

To address Hypothesis 2 of moderation of condition effects by implementation, we used the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Version 3.3, Hayes, 2018) with 5000 bootstrapped samples. These analyses showed no significant moderation of condition by implementation on story comprehension, story memory, or story quality.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that a 6-week combined reading-and-reminiscing (RRR) program with parents boosted children’s narrative production (retelling) skills one year later relative to a control group, both for their memory of the story and their use of dialogue, a type of story quality. Parent-reported implementation of the book-reading and reminiscing activities was high overall and did not moderate these effects. These findings are notable given that few parent-led book-reading interventions for children’s narrative skills exist, and none that we are aware of have shown long-term effects.

The benefits of parent-led RRR we found for children’s story memory and dialogue were moderate in strength, and in line with the findings from Pesco and Gagné’s (2017) meta-analysis of book-reading programs in early childhood settings. For instance, in Lever and Sénéchal’s (2011) study in which researchers delivered an enriched version of dialogic reading with small groups of 5- to 6-year-olds, they found benefits after 8 weeks for children’s narrative expression in terms of children’s inclusion of plot elements, internal states, and evaluatives. Likewise, Zevenbergen et al. (2003) found benefits of teacher- plus parent-led dialogic reading for children’s inclusion of internal states and dialogue in their later story retellings. With parents, Aram and colleagues noted stronger benefits for children’s story retelling of a 4-week meaning-focused book-reading program, especially in terms of internal state talk, than for children’s story comprehension (Fine et al., 2019). Likewise, Reese, Leyva, et al. (2010a) found stronger benefits of a reminiscing intervention for children’s story retelling than for their story comprehension.

To the best of our knowledge, only one other teacher-led study has found long-term significant effects in elementary school of a preschool book-reading intervention for children’s oral language skills (Whitehurst et al., 1999), and that study did not assess narrative skills. However, long-term effects for children’s narrative expression are common in the parent reminiscing intervention studies. For instance, Peterson et al. (1999) found benefits for children’s expressive narrative skills one year later as a function of a maternal reminiscing training study with Canadian low-income mothers. Moreover, in a reminiscing training study with low-income families in the U.S., narrative benefits for 4-year-old children were apparent approximately 6 months after the training session (Reese et al., 2010a). Finally, in a reminiscing training study with New Zealand mothers of toddlers, expressive narrative benefits were apparent 8 years after the intervention phase had ended, when children were 11 years old (Reese et al., 2020). The present study extends these longer-term narrative benefits to a combined reading-and-reminiscing program.

Moreover, the program appeared to be feasible for parents, who documented engaging in nearly all of the assigned activities. Although our implementation measure was limited to a parent report of dosage frequency, this high level of reported implementation is bolstered by our findings that parents continued to use the new techniques in their observed shared book-reading and reminiscing at the 1-year follow-up (Clifford et al., 2022b; Timperley et al., 2022). A meta-analysis of parent-led book-reading interventions that found a moderator effect of dosage for children’s language skills noted a much greater range in dose, from a mere 5 min at a well-child visit to 18 sessions in the children’s home (Dowdall et al., 2020). Given the dense dosage of Tender Shoots: RRR of 72 book-reading and conversational activities across the 6-week intervention, and parents’ reported overall high level of completion, it is not surprising that we found no significant moderating role of implementation.

The long-term narrative benefits we found are important given the critical role of children’s oral narrative skills in their later emergent literacy and reading skills (Gardner-Neblett & Iruka, 2015; Griffin et al., 2004; Reese et al., 2010a, 2010b; Schaughency et al., 2017) and academic achievement (O’Neill et al., 2004). For instance, New Zealand children’s story retelling skills in the first years of primary school uniquely predicted their later reading skill (Reese et al., 2010b; Schaughency et al., 2017).

Strengths, limitations, and future research

The primary strength of our study was that we showed oral narrative advantages of a brief parent-led book-reading and reminiscing intervention one year later. Other studies have tested children’s growth in oral narratives in response to intervention over the preschool year (e.g., Reese et al., 2010a; Zevenbergen et al., 2003), but no other study to our knowledge has followed children over the transition to primary school. These results are promising, given the posited links between these listening comprehension skills and later reading comprehension. Nonetheless, future research should directly examine benefits for reading comprehension at older ages when comprehension emerges as a construct separate to word level reading skills (e.g., US third grade; Lonigan & Burgess, 2017).

The main limitation of this study was the small sample size, and thus limited power to detect effects. The program was labor-intensive because of the prompted books and weekly book swaps, so would need to be streamlined if scaled up to larger groups of parents. Moreover, we cannot generalize these effects to families living in extreme poverty because our sample was relatively well-educated on average (albeit representing the full range of parental education levels in New Zealand). Although we do not know if our program would work as well with families outside New Zealand and those living in extreme poverty, it is notable that even the parents in our sample with only an intermediate-level (middle school) or high school education completed the program, and that parent education levels did not correlate with children’s follow-up narrative outcomes. Another limitation was that we did not include a standardized vocabulary measure that would enable us to test the unique benefits of our program for narrative skills after controlling for children’s vocabulary.

Because our program utilized a combined reading-and-reminiscing program, we were also unable to discern the unique value of either book-reading or reminiscing alone for children’s narrative skills. We argue that previous research has already demonstrated these unique benefits (e.g., Lever & Sénéchal, 2011; Reese et al., 2010a) so the next step was to weave these two techniques into a single program, similar to Aram et al. (2013). Nevertheless, it will be valuable in future research to ascertain the added value of the combined program over either book-reading or reminiscing alone. Given the barriers some parents face in implementing book-reading programs (Justice et al., 2015), it would be useful to know if reminiscing alone can deliver many of the same benefits.

Moreover, our meaning-based RRR version was not distinguishable from the soundplay SSS version in its effects on children’s narrative skills as we had hypothesized. Yet only the RRR condition, and not SSS, was significantly different from the control ABC condition on these narrative measures. In contrast, only the SSS condition, and not RRR, was significantly different from the control ABC condition on children’s beginning reading measures (Schaughency et al., 2022). Because both ways of reading and conversing have distinct benefits for children, future work should move beyond comparative evaluations of RRR and SSS to trials exploring the feasibility of delivering RRR and SSS in a sequence of modules for supporting adult–child interactions (parents and teachers) with young children (see Clifford et al., 2022a).

Conclusions

Our research shows that a brief reading-and-reminiscing program with parents and preschool children can help boost children’s narrative skills in primary school, which in turn may help children’s later reading skills and academic achievement. Families reported high completion rates of the program. We look forward to larger-scale implementations of Tender Shoots to assess benefits in early childhood settings and for children from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Availability of data

We will provide data upon request.

Code availability

None.

References

Aram, D., Fine, Y., & Ziv, M. (2013). Enhancing parent–child shared book reading interactions: Promoting references to the book’s plot and socio-cognitive themes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.03.005

Baker, D. L., Santoro, L., Biancarosa, G., Baker, S. K., Fien, H., & Otterstedt, J. (2020). Effects of a read aloud intervention on first grade student vocabulary, listening comprehension, and language proficiency. Reading and Writing, 33, 2697–2724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10060-2

Berman, R. A., & Slobin, D. I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Clifford, A., Schaughency, E., Das, S., Carroll, J., Riordan, J., & Reese, E. (2022b). Tender Shoots: Fostering parent-child reminiscing and socio-emotional development. Manuscript in preparation.

Clifford, A., Schaughency, E., Healey, D., Carroll, J., & Reese, E. (2022a). Tender Shoots: Fostering educator-child reminiscing and socio-emotional development in home-based early childhood education and care. Manuscript in preparation.

Das, S. (2018). Rich Reading and Reminiscing: Benefits of parent-preschooler interactions for children’s developing language, behavioural regulation, and socio-emotional competencies. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Dowdall, N., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Murray, L., Gardner, F., Hartford, L., & Cooper, P. J. (2020). Shared picture book reading interventions for child language development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Development, 91(2), e383–e399. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13225

Farrant, K., & Reese, E. (2000). Maternal style and children’s participation in reminiscing: Stepping stones in autobiographical memory development. Journal of Cognition and Development, 1, 193–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327647JCD010203

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage.

Fine, Y., Aram, D., & Ziv, M. (2019). Enriching parent-child discourse during book sharing. In E. Veneziano & A. Nicolopoulou (Eds.), Narrative, literacy and other skills: Studies in intervention (pp. 223–244). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fivush, R., Haden, C. A., & Reese, E. (2006). Elaborating on elaborations: Role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development, 77, 1568–1588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00960.x

Flack, Z. M., Field, A. P., & Horst, J. S. (2018). The effects of shared storybook reading on word learning: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 54(7), 1334–1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000512

Forget-Dubois, N., Dionne, G., Lemelin, J. P., Pérusse, D., Tremblay, R. E., & Boivin, M. (2009). Early child language mediates the relation between home environment and school readiness. Child Development, 80, 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01294.x

Gardner-Neblett, N., & Iruka, I. U. (2015). Oral narrative skills: Explaining the language-emergent literacy link by race/ethnicity and SES. Developmental Psychology, 51, 889–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039274

Griffin, T. M., Hemphill, L., Camp, L., & Wolf, D. P. (2004). Oral discourse in the preschool years and later literacy skills. First Language, 24, 123–147.

Haden, C. A., Reese, E., & Fivush, R. (1996). Mothers’ extratextual comments during storybook reading: Stylistic differences over time and across texts. Discourse Processes, 21(2), 135–169.

Harkins, D. A., Koch, P. E., & Michel, G. F. (1994). Listening to maternal story telling affects narrative skill of 5-year-old children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155(2), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1994.9914775

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Hindman, A. H., Connor, C. M., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2008). Untangling the effects of shared book reading: Multiple factors and their associations with preschool literacy outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 330–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.01.005

Hindman, A. H., Skibbe, L. E., & Foster, T. D. (2014). Exploring the variety of parental talk during shared book reading and its contributions to preschool language and literacy: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort. Reading and Writing, 27, 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.01.005

Hoff, E. (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26, 55–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002

Justice, L. M., Bowles, R., Pence, K., & Gosse, C. (2010). A scalable tool for assessing children’s language abilities within a narrative context: The NAP (Narrative Assessment Protocol). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.11.002

Justice, L. M., Logan, J. R., & Damschroder, L. (2015). Designing caregiver-implemented shared-reading interventions to overcome implementation barriers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58, 1851–1863.

Kang, J. Y., Kim, Y. S., & Pan, B. A. (2009). Five-year-olds’ book talk and story retelling: Contributions of mother-child joint bookreading. First Language, 29(3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723708101680

Keats, E. J. (1967). Peter’s chair. Harper & Row.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., Zucker, T., Crawford, A. D., & Solari, E. F. (2012). The effects of a responsive parenting intervention on parent–child interactions during shared book reading. Developmental Psychology, 48, 969–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026400

Lever, R., & Sénéchal, M. (2011). Discussing stories: On how a dialogic reading intervention improves kindergartners’ oral narrative construction. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108, 1–24.

Lonigan, C. J., & Burgess, S. R. (2017). Dimensionality of reading skills with elementary-school-age children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 21(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2017.1285918

Mashburn, A. J., LoCasale-Crouch, J., & Pears, K. C. (Eds.). (2018). Kindergarten transition and readiness. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90200-5

Mayer, M. (2008). Frog, where are you? Penguin Putnam Inc.

Miller, P. J., Potts, R., Fung, H., Hoogstra, L., & Mintz, J. (1990). Narrative practices and the social construction of self in childhood. American Ethnologist, 17, 292–311. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1990.17.2.02a00060

Milne, B., Byun, U., & Lee, A. (2013). New Zealand socio-economic Index 2006 (NZSEI-06). An update and 443 revision of the New Zealand Socio-economic Index of Occupational Status. Auckland, NZ: University of Auckland.

Mitchell, C., & Reese, E. (2022). Growing Memories: Coaching mothers in elaborative reminiscing with toddlers benefits adolescents’ turning point narratives and wellbeing. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12703

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., De Jong, M. T., & Smeets, D. J. (2008). Added value of dialogic parent–child book readings: A meta-analysis. Early Education and Development, 19, 7–26.

Mullen, M. K., & Yi, S. (1995). The cultural context of talk about the past: Implications for the development of autobiographical memory. Cognitive Development, 10, 407–419.

O’Neill, D. K., Pearce, M. J., & Pick, J. L. (2004). Preschool children’s narratives and performance on the Peabody Individualized Achievement Test–Revised: Evidence of a relation between early narrative and later mathematical ability. First Language, 24, 149–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723704043529

Pesco, D., & Gagné, A. (2017). Scaffolding narrative skills: A meta-analysis of instruction in early childhood settings. Early Education and Development, 28, 773–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.1060800

Peterson, C., Jesso, B., & McCabe, A. (1999). Encouraging narratives in preschoolers: An intervention study. Journal of Child Language, 26, 49–67.

Raikes, H., Alexander Pan, B., Luze, G., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Constantine, J., & Rodriguez, E. T. (2006). Mother–child bookreading in low-income families: Correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Development, 77, 924–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00911.x

Reese, E. (2019). Learning language from books. In J. S. Horst and J. von Koss Torkildsen’s (Eds.), International Handbook of Language Development (pp. 462–484). UK: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Reese, E. (1995). Predicting children’s literacy from mother-child conversations. Cognitive Development, 10(3), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-2014(95)90003-9

Reese, E. (1999). What children say when they talk about the past. Narrative Inquiry, 9, 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.9.2.02ree

Reese, E. (2012). The tyranny of shared book-reading. In S. Suggate & E. Reese (Eds.), Contemporary debates in childhood education and development (pp. 59–68). Routledge.

Reese, E. (2013). Tell me a story: Sharing stories to enrich your child’s world. Oxford University Press.

Reese, E. (2018). Encouraging collaborative remembering between young children and their caregivers. In M. L. Meade, C. B. Harris, P. Van Bergen, J. Sutton, & A. Barnier (Eds.), Collaborative remembering: Background and approaches (pp. 317–333). Oxford University Press.

Reese, E., & Cox, A. (1999). Quality of adult book reading affects children’s emergent literacy. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.20

Reese, E., Leyva, D., Sparks, A., & Grolnick, W. (2010a). Maternal elaborative reminiscing increases low-income children’s narrative skills relative to dialogic reading. Early Education and Development, 21, 318–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.481552

Reese, E., Macfarlane, L., McAnally, H., Robertson, S. J., & Taumoepeau, M. (2020b). Coaching in maternal reminiscing with preschoolers leads to elaborative and coherent personal narratives in early adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 189, 104707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104707

Reese, E., & Newcombe, R. (2007). Training mothers in elaborative reminiscing enhances children’s autobiographical memory and narrative. Child Development, 78, 1153–1170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01058.x

Reese, E., Robertson, S. J., Divers, S., & Schaughency, E. (2015). Does the brown banana have a beak? Preschool children’s phonological awareness as a function of parents’ talk about speech sounds. First Language, 35(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723714566336

Reese, E., Suggate, S., Long, J., & Schaughency, E. (2010b). Children’s oral narrative and reading skills in the first 3 years of reading instruction. Reading and Writing, 23, 627–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-009-9175-9

Riordan, J., Reese, E., Carroll, J., Das, S., & Schaughency, E. (2021). Tender Shoots: A randomized controlled trial of two shared reading approaches for enhancing parent-child interactions and children’s oral language and literacy skills. Scientific Studies of Reading. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2021.1926464

Robertson, S. J. L., & Reese, E. (2017). The very hungry caterpillar turned into a butterfly: Children’s and parents’ enjoyment of different book genres. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17, 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415598354

Rowe, M. L. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Development, 83, 1762–1774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01805.x

Salmon, K., & Reese, E. (2016). The benefits of reminiscing with young children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416655100

Schaughency, E., Linney, K., Carroll, J., Das, S., Riordan, J., & Reese, E. (2022). Tender Shoots: A parent-mediated randomized controlled trial with preschool children benefits beginning reading one year later. Manuscript under review.

Schaughency, E., Suggate, S., & Reese, E. (2017). Links between early oral narrative and decoding skills and later reading in a New Zealand sample. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 22, 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2017.1399914

Schröder, L., Dintsioudi, A., List, M. K., & Keller, H. (2019). Teachers’ conversational style and children’s language development in German childcare centers: A culture-sensitive intervention. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(2), 164–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118812174s

Şimşek, Z. C., & Erdoğan, N. I. (2021). Comparing the effects of different book reading techniques on young children’s language development. Reading and Writing, 34(4), 817–839.

Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., Slocum, T. A., & Allen, M. M. (2015). Large group narrative intervention in Head Start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13(2), 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X13515419

Suggate, S., Schaughency, E., McAnally, H., & Reese, E. (2018). From infancy to adolescence: The longitudinal links between vocabulary, early literacy skills, oral narrative, and reading comprehension. Cognitive Development, 47, 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.04.005

Timperley, S., Schaughency, E., Riordan, J., Carroll, J. L. D., Das, S., & Reese, E. (2022). Tender Shoots: Effects of a preschool shared book-reading preventive intervention on parent-child reading and parents’ involvement in the first year of school. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09505-6

van Kleeck, A., Gillam, R. B., Hamilton, L., & McGrath, C. (1997). The relationship between middle-class parents’ book-sharing discussion and their preschoolers’ abstract language development. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 1261–1271.

Veneziano, E. & Nicolopoulou, A. (Eds.), Narrative, literacy and other skills: Studies in intervention (pp. 223–244). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Wang, Q. (2001). “Did you have fun?”: American and Chinese mother–child conversations about shared emotional experiences. Cognitive Development, 16, 693–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(01)00055-7

Wasik, B. A., Bond, M. A., & Hindman, A. (2006). The effects of a language and literacy intervention on Head Start children and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.63

Wasik, B. A., Hindman, A. H., & Snell, E. K. (2016). Book reading and vocabulary development: A systematic review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.04.003

Waters, T. E., Camia, C., Facompré, C. R., & Fivush, R. (2019). A meta-analytic examination of maternal reminiscing style: Elaboration, gender, and children’s cognitive development. Psychological Bulletin, 145(11), 1082–1102. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000211

Westerveld, M. F., & Vidler, K. (2014, May). The use of the Renfrew Bus Story with 5–8-year-old Australian children. Paper presented at the National Conference of Speech Pathology Australia, Melbourne, Australia.

Whitehurst, G. J., Epstein, J. N., Angell, A. L., Payne, A. C., Crone, D. A., & Fischel, J. E. (1994). Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention in Head Start. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 542–555. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.86.4.542

Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., Lonigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., & Caulfield, M. (1988). Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Developmental Psychology, 24, 552–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.552

Whitehurst, G. J., Zevenbergen, A. A., Crone, D. A., Schultz, M. D., Velting, O. N., & Fischel, J. E. (1999). Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention from Head Start through second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 261–272.

Zevenbergen, A. A., Whitehurst, G. J., & Zevenbergen, J. A. (2003). Effects of a shared-reading intervention on the inclusion of evaluative devices in narratives of children from low-income families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00021-2

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families, early childhood centres, and schools who participated in this research, and to the University of Otago Division of Sciences for funding. We also thank the Getting Ready for School team for their help.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was supported by a grant from the University of Otago Division of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study received ethical approval from the University of Otago Ethics Committee.

Consent to participate

All parents provided written consent for themselves and their children to participate.

Consent for publication

All authors have provided their consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Story Comprehension Questions.

Pre-test (Peter’s Chair).

-

1.

What was the boy’s name in the story?

-

2.

What was his little sister’s name?

-

3.

Why did Peter want to run away from home?

-

4.

What are some of the things Peter took with him when he ran away?

-

5.

At the end of the story, what did Peter do with the chair?

-

6.

Why do you think he did that?

One-Year Follow-Up (Frog, Where Are You?).

-

1.

Who was the story about?

-

2.

Where did the boy keep his pet frog?

-

3.

What happened to the frog at the beginning of the story?

-

4.

Did the boy have trouble finding the frog? Explain.

-

5.

Did the boy get what he wanted? Explain.

-

6.

What happened at the end of the story?

Appendix B

Example of a 1-Year Story Retell (RRR).

R = researcher; C = child; P = Paddles the Penguin voice.

R: I can help you start. It’s called “Frog, where are you?”.

C: Frog, where are you. They kept the frog in a jar and… next page.

P: Mmhmm.

C: Uh they were sleeping and the dog um the frog went got out of the jar.

P: Oh no.

C: Then they woke up next morning and then the frog was gone.

P: Ohh.

C: They looked everywhere and even in the boots and even the dog got his head stuck in the jar because he was looking in there.

P: Mmmmm.

C: “Frog, where are you?” they shouted out the window.

P: You’re telling me a great story.

C: And then the dogs fell and then the jar smashed.

P: Mmm.

C: They called out, “Frog, frog, frog where are you?” Then they saw a beehive. And they looked down the hole. “Where are you frog? Where are you?” And then it was a mole jumped up and on the boy’s nose and the dog kept on.

P: Mmhmm.

C: Um kept on barking at the beehive. And then the beehive fell and the bees were very angry at the dog.

P: Mmm.

C: And the boy climbed up a tree. He didn’t care about the dog. He he saw a really large hole. He said, “Frog, where are you?”.

P: Mmmm.

C: And there was a big owl inside.

P: Mmm.

C: And it said, “Don’t ignore um stop stop” I can’t remember.

R: That’s alright. What could it have said?

C: “Don’t go in my territory”.

P: Ohh you’re telling me a great story thank you.

C: And then the boy fell down.

P: Mmhmm.

C: The bees got real angry so the faces went red.

P: Oohh.

C: And the dog jumped and jumped. They looked behind but the boy um hide behind a big large rock.

P: Mmhmm.

C: And then he climbed up it on some and he saw some he found some branches but they weren’t branches they were antlers.

P: Ohhoh.

C: Deer’s antlers. And the deer picked the boy up and ran towards the very large cliff. And the reindeer stopped um chucked the boy and the dog down.

P: Mmhmm.

C: And then they fell down and and they fell into a very large um pond and luckily they had a big smash and they heard a ribbit sound, “Ribbit ribbit.” And then the boy said, “Sshhh, dog” and then they looked behind the log.

P: Mmhmm.

C: And then um they saw fr- frog a frogs and some baby frogs jumping along and one of the baby frogs jumped to the boy and he liked it. And and the boy said, “Bye frogs.” The end.

P: Thank you for telling me such a great story.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reese, E., Barrett-Young, A., Gilkison, L. et al. Tender Shoots: a parent book-reading and reminiscing program to enhance children’s oral narrative skills. Read Writ 36, 541–564 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10282-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10282-6