Abstract

The theoretical literature on price-matching guarantees (PMGs) finds that this policy has both a competition-softening and a competition-enhancing effect. Which effect dominates depends on market structure. This paper is the first to propose a structural framework to measure the impact of PMGs on market competition through a counterfactual analysis. The structural model proposed here can be estimated using price data alone. I estimate the model using data from the automotive tire market, and I find that the competition-softening effect is stronger than the competition-enhancing effect. PMGs keep transaction prices between 1% and 8% higher than they would be in the absence of such policy. PMGs exert the strongest effect on price-sensitive consumers, who tend to be the poorest. This consumer segment pays up to 10% higher prices in the presence of PMGs. The tire market has some unique features that facilitate the competition-enhancing effect of PMGs. Hence, that the competition-softening effect dominates even in the tire market suggests that PMGs may increase prices in many other markets, too.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hviid and Shaffer (1999) provide two examples: the day after Esso announced the introduction of a PMG, a headline in the Financial Times read “Petrol Rivals on Price-War Footing”; after Tesco’s decision to adopt price-matching, a headline in the Financial Times read “Tesco Launches a New Price-War.”

According to Modern Tire Dealer ??http://www.moderntiredealer.com/article/312475/competing-against-your- ??supplier and the Stevenson Company ??https://stevensoncompany.com/amazon-online-retailer-share-lame- ??dominating-game/.

Alternatively, it could be assumed that uninformed consumers become informed about the pricing strategies of n firms after purchase with probability q.

A firm that offers a PMG needs to advertise it, to acquire the software necessary for processing the refunds, and to hire qualified personnel to work with said software.

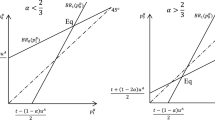

Both πPMG(p) and πNO(p) are characterized in Online Appendix ?? A.

In the equilibrium analysis presented in Online Appendix ?? A, I discuss how z is obtained.

Moorthy and Winter (2006) survey 46 retailers and ask for the managers’ perception of usage rates of PMGs. They find that managers perceive that PMGs are used by 5% of consumers.

DMAs are defined by Nielsen Media Research as geographic areas consisting of groups of counties that share the same home-market television stations. DMAs are geographical areas of roughly the same size as Metropolitan Statistical Areas.

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/illinois/10-richest-counties-il/ Published December 30, 2015. Illinois has 102 counties.

All calls were made between November 3, 2014, and November 6, 2014. The details regarding how I asked whether a firm offers a PMG appear in Online Appendix ?? C.

Forty-two stores did not carry the tires we were asking for, and eight stores did not answer the phone. Of the 346 stores in the data, 337 carry the Defender tire and 278 carry the Premier tire.

The model cannot identify the distribution of costs that firms face to provide a PMG. Instead, it is only possible to identify the share of firms that, in equilibrium, choose to offer a PMG (which is denoted by α). This, however, does not constitute a problem, because the distribution of costs that firms face to provide a PMG has no implications on the counterfactual equilibrium.

The equilibrium price distributions are computed using numerical methods, where there is a discrete set of potential prices. I therefore compute the distance between these discrete equilibrium price distributions and the observed price distributions.

These two tires are directed toward different consumer segments. The Premier is a grand-touring tire geared toward owners of fast premium cars, while the Defender is a standard touring tire for regular cars.

Even if consumers have a spare tire, it is typically a smaller tire that is recommended not to be used for more than 50 miles.

Because uninformed consumers search at random and purchase at the first firm they visit, only 40% of uninformed consumers purchase from a PMG store. For the Defender, where n = 2, uninformed consumers who purchase at a PMG store will collect refunds only if the price of the other store is lower. Because the probability that a PMG store has a lower price than a non-PMG store is higher than 50%, it follows that at most half of the consumers who purchase from a PMG store collect refunds.

In the base model, I assume, for simplicity, that informed consumers are costlessly informed about prices of n firms. In the robustness section, presented in Online Appendix ?? F, I consider the case in which these consumers face a search cost per firm they sample, and they choose how many firms to contact; in this more realistic setting, I also estimate the search cost of matchers and shoppers.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., & Gowrisankaran, G. (2006). Quantifying equilibrium network externalities in the ach banking industry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3), 738–761.

Aguirregabiria, V. (1999). The dynamics of markups and inventories in retailing firms. The Review of Economic Studies, 66(2), 275–308.

Anderson, T. W., & Darling, D. A. (1952). Asymptotic theory of certain goodness of fit criteria based on stochastic processes. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 193–212.

Arbatskaya, M., Hviid, M., & Shaffer, G. (1999). Promises to match or beat the competition: evidence from retail tire prices. Advances in Applied Microeconomics, 8, 123–138.

Arbatskaya, M., Hviid, M., & Shaffer, G. (2004). ON the incidence and variety of low-price guarantees. Journal of Law and Economics, 47, 307.

Arbatskaya, M., Hviid, M., & Shaffer, G. (2006). On the use of low-price guarantees to discourage price-cutting: a test for pairwise-facilitation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24, 1139–1156.

Bartlett, J. S. (2017). Driving forces behind tire purchases revealed in cr’s exclusive survey. Consumer Reports.

Baye, M. R., & Kovenock, D. (1994). How to sell a pickup truck:’beat-or-pay’advertisements as facilitating devices. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 12(1), 21–33.

Belton, T. M. (1987). A model of duopoly and meeting or beating competition. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 5(4), 399–417.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Smith, M. D. (2000). Frictionless commerce? a comparison of internet and conventional retailers. Management Science, 46(4), 563–585.

Burdett, K., & Judd, K. L. (1983). Equilibrium price dispersion. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 955–969.

Chandra, A., & Weinberg, M. (2018). How does advertising depend on competition? evidence from us brewing. Management Science, 64(11), 5132–5148.

Chen, Y., Narasimhan, C., & Zhang, Z. (2001). COnsumer heterogeneity and competitive price-matching guarantees. Marketing Science, 20, 300–314.

Chen, Z. (1995). How low is a guaranteed-lowest-price?Canadian Journal of Economics, 683–701.

Clay, K., Krishnan, R., & Wolff, E. (2001). Prices and price dispersion on the web: evidence from the online book industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 49(4), 521–539.

Delgado, J., & Waterson, M. (2003). Tyre price dispersion across retail outlets in the uk. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 51(4), 491–509.

Doyle, C. (1988). DIfferent selling strategies in Bertrand oligopoly. Economics Letters, 28, 387–390.

Edlin, A. (1997). Do guaranteed-low-price policies guarantee high prices, and can antitrust rise to the challenge?. Harvard Law Review, 111, 528–575.

Efron, B. (1982). The jackknife, the bootstrap and other resampling plans. SIAM.

Efron, B. (1987). Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82(397), 171–185.

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (1986). Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Statistical Science, 54–75.

Hess, J., & Gerstner, E. (1991). Price-matching policies: an empirical case. Managerial and Decision Economics, 12, 305–315.

Hong, H., & Shum, M. (2006). USing price distributions to estimate search costs. RAND Journal of Economics, 37, 257–275.

Houde, J. -F. (2012). Spatial differentiation and vertical mergers in retail markets for gasoline. American Economic Review, 102(5), 2147–82.

Hviid, M., & Shaffer, G. (1999). Hassle costs: the Achilles heel of price-matching guarantees. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 8, 489–522.

Hviid, M., & Shaffer, G. (2012). Optimal low-price guarantees with anchoring. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 10(4), 393–417.

Iyer, G. (1998). Coordinating channels under price and nonprice competition. Marketing Science, 17(4), 338–355.

Janssen, M., & Parakhonyak, A. (2013). PRice matching guarantees and consumer search. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 31, 1–11.

Power, J.D. (2017). U.s. original equipment tire customer satisfaction study.

Jiang, J., Kumar, N., & Ratchford, B. T. (2016). Price-matching guarantees with endogenous consumer search. Management Science.

Kalai, E., & Satterthwaite, M. A. (1994). The kinked demand curve, facilitating practices, and oligopolistic coordination. Imperfections and Behavior in Economic Organizations, 15–38.

Kaplan, G., Menzio, G., Rudanko, L., & Trachter, N. (2019). Relative price dispersion Evidence and theory. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 11(3), 68–124.

Kohn, M. G., & Shavell, S. (1974). The theory of search. Journal of Economic Theory, 9(2), 93–123.

Lach, S. (2002). Existence and persistence of price dispersion: an empirical analysis. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(3), 433–444.

Logan, J. W., & Lutter, R. W. (1989). Guaranteed lowest prices: do they facilitate collusion? Economics Letters, 31(2), 189–192.

Lu, Q., & Moorthy, S. (2007). Coupons versus rebates. Marketing Science, 26(1), 67–82.

Mañez, J. (2006). Unbeatable value low price guarantee: collusion mechanism or advertising strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 15, 143–166.

Mamadehussene, S. (2019). Price-matching guarantees as a direct signal of low prices. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(2), 245–258.

Moorthy, S., & Winter, R. (2006). PRice-matching guarantees. RAND Journal of Economics, 37, 449–465.

Moraga-Gonzalez, J. L., & Wildenbeest, M. R. (2008). Maximum likelihood estimation of search costs. European Economic Review, 52, 820–848.

Narasimhan, C. (1984). A price discrimination theory of coupons. Marketing Science, 3(2), 128–147.

Narasimhan, C. (1988). Competitive promotional strategies. Journal of Business, 427–449.

Nishida, M., & Remer, M. (2018). The determinants and consequences of search cost heterogeneity: Evidence from local gasoline markets. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(3), 305–320.

Phillips, G., & Sertsios, G. (2013). How do firm financial conditions affect product quality and pricing? Management Science, 59(8), 1764–1782.

Png, I., & Hirshleifer, D. (1987). PRice discrimination through offers to match price. Journal of Business, 60, 365–383.

Reny, P. J. (1999). ON the existence of pure and mixed strategy Nash equilibria in discontinuous games. Econometrica, 67, 1029–1056.

Rust, J. (1987). Optimal replacement of gmc bus engines: An empirical model of harold zurcher. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 999–1033.

Salop, S. (1986). Practices that (credibly) facilitate oligopoly coordination. In J. Stiglitz F. Mathewson (Eds.) New Developments in the Analysis of Market Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sorensen, A. T. (2000). Equilibrium price dispersion in retail markets for prescription drugs. Journal of Political Economy, 108(4), 833–850.

Stahl, D. O. (1989). Oligopolistic pricing with sequential consumer search. The American Economic Review, 700–712.

Varian, H. (1980). A Model of sales. American Economic Review, 70, 651–659.

Verboven, F. (2002). Quality-based price discrimination and tax incidence: evidence from gasoline and diesel cars. RAND Journal of Economics, 275–297.

Wildenbeest, M. R. (2011). An empirical model of search with vertically differentiated products. The RAND Journal of Economics, 42(4), 729–757.

Zhang, Z. J. (1995). Price-matching policy and the principle of minimum differentiation. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 287–299.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mamadehussene, S. Measuring the competition effects of price-matching guarantees. Quant Mark Econ 19, 261–287 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-021-09242-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-021-09242-1