Abstract

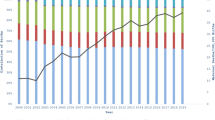

Medicaid-funded obstetric care coordination programs supplement prenatal care with tailored services to improve birth outcomes. It is uncertain whether these programs reach populations with elevated risks of adverse birth outcomes—namely non-white, highly rural, and highly urban populations. This study evaluates racial and geographic variation in the receipt of Wisconsin Medicaid’s Prenatal Care Coordination (PNCC) program during 2010–2019. We sample 250,596 Medicaid-paid deliveries from a cohort of linked Wisconsin birth records and Medicaid claims. We measure PNCC receipt during pregnancy dichotomously (none; any) and categorically (none; assessment/care plan only; service receipt), and we stratify the sample on three maternal characteristics: race/ethnicity, urbanicity of residence county; and region of residence county. We examine annual trends in PNCC uptake and conduct logistic regressions to identify factors associated with assessment or service receipt. Statewide PNCC outreach decreased from 25% in 2010 to 14% in 2019, largely due to the decline in beneficiaries who only receive assessments/care plans. PNCC service receipt was greatest and persistent in Black and Hispanic populations and in urban areas. In contrast, PNCC service receipt was relatively low and shrinking in American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, and white populations and in more rural areas. Additionally, being foreign-born was associated with an increased likelihood of getting a PNCC assessment in Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic populations, but we observed the opposite association in Black and white populations. Estimates signal a gap in PNCC receipt among some at-risk populations in Wisconsin, and findings may inform policy to enhance PNCC outreach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Per data use agreements with providers, data for this project are not publicly available.

References

March of Dimes (2022, January). Preterm Birth. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99⊤=3&stop=63&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1

March of Dimes (2022, January). Birthweight. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99⊤=4&stop=45&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J. K., Curtin, S. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2015). Births: Final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports, 64(1), 1–68.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J. K., Driscoll, A. K., & Mathews, T. J. (2017). Births: Final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports, 66(1), 1–70.

Osterman, M. J. K., Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., Driscoll, A. K., & Valenzuela, C. P. (2023). Births: Final data for 2021. National Vital Statistics Reports, 72(1), 1–53.

Hulme, P. A., & Blegen, M. A. (1999). Residential status and birth outcomes: Is the rural/urban distinction adequate? Public Health Nursing, 16(3), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1446.1999.00176.x.

Hillemeier, M. M., Weisman, C. S., Chase, G. A., & Dyer, A. M. (2007). Individual and community predictors of preterm birth and low birthweight along the rural-urban continuum in central Pennsylvania. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00066.x.

Bailey, B. A., & Cole, L. K. J. (2009). Rurality and birth outcomes: Findings from southern Appalachia and the potential role of pregnancy smoking. The Journal of Rural Health, 25(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00210.x.

Rosenberg, M. (2014). Health geography I: Social Justice, idealist theory, health and health care. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513498339.

Holcomb, D. S., Pengetnze, Y., Steele, A., Karam, A., Spong, C., & Nelson, D. B. (2021). Geographic barriers to prenatal care access and their consequences. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 3(5), 100442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100442.

March of Dimes (2022). 2022 March of Dimes Report Card: Stark and Unacceptable Disparities Persist Alongside a Troubling Rise in Preterm Birth Rates. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/March-of-Dimes-2022-Full-Report-Card.pdf.

Barker, D. J. P., Eriksson, J. G., Forsen, T., & Osmond, C. (2002). Fetal origins of adult disease: Strength of effects and biological basis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), 1235–1239. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.6.1235.

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., & Beedle, A. S. (2007). Early life events and their consequences for later disease: A life history and evolutionary perspective. American Journal of Human Biology, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20590.

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Cooper, C., & Thornburg, K. L. (2008). Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0708473.

Calkins, K., & Devaskar, S. U. (2011). Fetal origins of adult disease. Current Problems in Pediatrics and Adolescent Health Care, 41(6), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2011.01.001.

Lu, M. C. (2014). Improving maternal and child health across the life course: Where do we go from here? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(2), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1400-0.

Kroll-Desrosiers, A. R., Crawford, S. L., Simas, M., Rosen, T. A., A. K., & Mattocks, K. M. (2016). Improving outcomes through maternity care coordination: A systematic review. Womens Health Issues, 26(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.10.003.

Lee, H., Crowne, S., Faucetta, K., & Hughes, R. (2016). An Early Look at Families and Local Programs in the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation-Strong Start: Third Annual Report. New York, NY: MDRC.

Strobel, N. A., Arabena, K., East, C. E., Schultz, E. M., Kelaher, M., Edmond, K. M. Care co-ordination interventions to improve outcomes during pregnancy and early childhood (up to 5 years). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(8), CD012761. https://doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD012761.

Hill, I., Dubay, L., Courtot, B., Benatar, S., Garrett, B., Blavin, F., et al. (2018). Strong start for mothers and newborns evaluation: Year 5 project synthesis volume 1: Cross-cutting findings. Urban Institute.

Gallagher, J., Botsko, C., & Schwalberg, R. (2004). Influencing interventions to promote positive pregnancy outcomes and reduce the incidence of low Birth Weight and Preterm infants. Health Systems Research Inc.

Hill, I. T. (1990). Improving state Medicaid programs for pregnant women and children. Health Care Financing Review,1990(Suppl), 75–87.

Buescher, P. A., Roth, M. S., Williams, D., & Goforth, C. M. (1991). An evaluation of the impact of maternity care coordination on Medicaid birth outcomes in North Carolina. American Journal of Public Health, 81(12), 1625–1629. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.81.12.1625.

Reichman, N. E., & Florio, M. J. (1996). The effects of enriched prenatal care services on Medicaid birth outcomes in New Jersey. Journal of Health Economics, 15(4), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00491-2.

Baldwin, L. M., Larson, E. H., Connell, F. A., Nordlund, D., Cain, K. C., Cawthon, M. L., et al. (1998). The effect of expanding Medicaid prenatal services on birth outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 88(11), 1623–1629. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.88.11.1623.

Van Dijk, J. W., Anderko, L., & Stetzer, F. (2011). The impact of prenatal care coordination on birth outcomes. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 40(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01206.x.

Slaughter, J. C., Issel, L. M., Handler, A. S., Rosenberg, D., Kane, D. J., & Stayner, L. T. (2013). Measuring dosage: A key factor when assessing the relationship between prenatal case management and birth outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(8), 1414–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10995-012-1143-3.

Hillemeier, M. M., Domino, M. E., Wells, R., Goyal, R. K., Kum, H. C., Cilenti, D., et al. (2015). Effects of maternity care coordination on pregnancy outcomes: Propensity-weighted analyses. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(1), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1502-3.

Roman, L., Raffo, J. E., Zhu, Q., & Meghea, C. I. (2014). A statewide Medicaid enhanced prenatal care program: Impact on birth outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(3), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4347.

Mallinson, D. C., Larson, A., Berger, L. M., Grodsky, E., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2020). Estimating the effect of prenatal care coordination in Wisconsin: A sibling fixed effects analysis. Health Services Research, 55(1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13239.

Meghea, C. I., Raffo, J. E., Zhu, Q., & Roman, L. (2013). Medicaid home visitation and maternal and infant healthcare utilization. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(4), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.005.

Hillemeier, M. M., Domino, M. E., Wells, R., Goyal, R. K., Kum, H. C., Cilenti, D., et al. (2017). Does maternity care coordination influence perinatal health care utilization? Evidence from North Carolina. Health Services Research, 53(4), 2368–2383. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12742.

Mallinson, D. C., Elwert, F., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2023). Spillover effects of prenatal care coordination on older siblings beyond the mother-infant dyad. Medical Care, 61(4), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001822.

Larson, A., Berger, L. M., Mallinson, D. C., Grodsky, E., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2019). Variable uptake of Medicaid-covered prenatal care coordination: The relevance of treatment level and service context. Journal of Community Health, 44(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0550-9.

Institute for Research on Poverty. The Wisconsin Administrative Data Core. Retrieved December 15 (2023). from https://www.irp.wisc.edu/wadc/.

Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid & CHIP coverage. Retrieved December 15 (2023). from https://www.healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/getting-medicaid-chip/.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (2023, April). Prenatal Care Coordination. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/pncc/index.htm.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. ForwardHealth Online Handbook: Published Policy through 10/31/ (2018). Prenatal Care Coordination. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.forwardhealth.wi.gov/kw/archive/PNCC110118.pdf.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. ForwardHealth Prenatal Care Coordination Pregnancy Questionnaire. Retrieved December 1 (2023). from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/forms/f0/f01105.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017, June). NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (2023, January). DHS Regions by County. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/aboutdhs/regions.htm.

StataCorp. (2023). Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. StataCorp LLC.

Esri Inc. (2023). ArcGIS Online. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2020, September). New Data on State Health Agencies Show Shrinking Workforce and Decreased Funding Leading Up to COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved January 22, 2024, from https://www.astho.org/communications/newsroom/older-releases/new-sha-data-shows-shrinking-workforce-decreased-funding-leading-to-covid-19-pandemic/.

Wisconsin Hospital Association (2019). Wisconsin 2019 Health Care Workforce Report Retrieved January 22, 2024, from https://www.wha.org/MediaRoom/DataandPublications/WHAReports/Workforce/2019/2019-WHA-Workforce-Report.pdf.

Wisconsin Hospital Association (2023). 2023 Wisconsin Health Care Workforce Report Retrieved January 22, 2024, from https://www.wha.org/MediaRoom/DataandPublications/WHAReports/Workforce/2023/Report/WHA-Workforce-Report-2023-web-(1).

Zhang, X., Tai, D., Pforsich, H., & Lin, V. W. (2018). United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast: A revisit. American Journal of Medical Quality, 33(3), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617738328.

Douthit, N., Kiv, S., Dwolatzky, T., & Biswas, S. (2015). Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health, 129(6), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001.

MacQueen, I. T., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Capra, G., et al. (2018). Recruiting rural healthcare providers today: A systematic review of training program success and determinants of geographic choices. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4210-z.

Greene, M. Z., Gillespie, K. H., & Dyer, R. L. (2023). Contextual and policy influences on the implementation of Prenatal Care Coordination. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 24(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/15271544231159655.

March of Dimes (2023). 2023 March of Dimes Report Card for Wisconsin. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/reports/wisconsin/report-card.

Smith, M. A., Hendricks, K. A., Bednarz, L. M., et al. (2021). Identifying substantial racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes and care in Wisconsin using electronic health record data. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 120(Suppl 1), S13–S16.

March of Dimes (2023). Where You Live Matters: Maternity Care Access in Wisconsin. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/reports/wisconsin/maternity-care-deserts.

Wisconsin Office of Rural Health (2019, July). Obstetric Delivery Services and Workforce in Rural Wisconsin Hospitals. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://worh.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ObstetricServicesReport2018Revised.pdf.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (2023, February). Civil Rights: Limited English Proficiency Resources. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/civil-rights/lep-resources.htm.

Proctor, K., Wilson-Frederick, S. M., & Haffer, S. C. (2018). The Limited English proficient population: Describing Medicare, Medicaid, and dual beneficiaries. Health Equity, 2(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2017.0036.

Greene, M., Tran-Smith, Z., & Moua, B. (2022). Beyond common outcomes: Client’s perspectives on the benefits of prenatal care coordination. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.22273331.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (2022, March). African Americans in Wisconsin: Overview. Retrieved January 22, 2024, from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/minority-health/population/afriamer-pop.htm.

Spivak, C., & Spicuzza, M. (2022, January 30). Fraud in prenatal care industry – Cash Not Care - Black babies in Milwaukee are dying at a staggering rate. Taxpayers are spending millions on the problem. But signs of fraud are surging. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, A1.

Spicuzza, M., & Spivak, C. (2023, February 13). Prenatal care firm accused of fraud – Milwaukee company’s Medicaid funding cut. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, A1.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (2023, November). DHS Announces New Accountability Measures for Medicaid Providers to Ensure Families Receive Critical, Effective Post-Birth Care Services. Retrieved January 5, 2024, from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/news/releases/111023.htm.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Child Care Coordination Services. Retrieved December 15 (2023). from https://www.forwardhealth.wi.gov/kw/pdf/ccc.pdf.

Liu, C. H., Goyal, D., Mittal, L., & Erdei, C. (2021). Patient satisfaction with virtual-based prenatal care: Implications after the COVID-19 pandemic. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(11), 1735–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03211-6.

Futterman, I., Rosenfeld, E., Toaff, M., Boucher, T., Golden-Espinal, S., Evans, K., et al. (2021). Addressing disparities in prenatal care via telehealth during COVID-19: Prenatal satisfaction survey in east Harlem. American Journal of Perinatology, 38(1), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718695.

Javaid, S., Barringer, S., Compton, S. D., Kaselitz, E., Muzik, M., & Moyer, C. A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on prenatal care in the United States: Qualitative analysis from a survey of 2519 pregnant women. Midwifery, 98, 102991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.102991.

Hargis-Villanueva, A., Lai, K., van Leeuwen, K., Weidler, E. M., Felts, J., Schmidt, A., et al. (2022). Telehealth multidisciplinary prenatal consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Enhancing patient care coordination while maintaining provider satisfaction. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 35(25), 9765–9769. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2022.2053101.

Ojo, A., Beckman, A. L., Weiseth, A., & Shah, N. (2022). Ensuring racial equity in pregnancy care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 26(4), 747–750. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10995-021-03194-4.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services for providing data, and we thank Lawrence Berger and Madelyne Greene for comments. The design and conduct of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of supporting agencies. Additionally, supporting agencies do not certify the accuracy of the analyses presented.

Funding

This work was supported by the following sources: the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD102125); the Health Resources and Services Administration through the University of Wisconsin Primary Care Research Fellowship (T32HP10010); and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Clinical & Translational Research (ICTR) with support from NIH-NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) 1UL1TR002373 and funds through a grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program (WPP 5129) at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, DCM, KHG; Methodology, DCM; Interpretation, DCM, KHG; Data curation, DCM; Writing—original draft preparation, DCM; Writing—review and editing, KHG; Funding acquisition, DCM. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison minimal risk institutional review board.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

The study did not directly involve human participants and/or animals.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallinson, D.C., Gillespie, K.H. Racial and Geographic Variation of Prenatal Care Coordination Receipt in the State of Wisconsin, 2010–2019. J Community Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01338-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01338-5