Abstract

This article deals with individuals of immigrant background in Swedish higher education—i.e., those who have a PhD and work in Swedish universities. The aim of the study is to examine whether and how factors other than academic qualifications—such as gender and migrant background—may affect the individual’s ability to find employment and pursue a successful career in a Swedish institution of higher education. The data used in the first section are Swedish registry data (LISA database and population), administered by Statistics Sweden. The second part of the paper is based on semi-structured interviews with 19 academics of migrant background. The results show that, given the same work experience and compared to the reference group (born in Sweden with at least one Swedish-born parent), individuals born in Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America are, firstly, more likely to be unemployed and, secondly, if they are employed, to have a lower income (lower position). The ways in which such gaps arises are also examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In line with earlier research, Becher and Trowler (2001: 153) write, “As with gender, the structural inequalities associated with race and ethnicity in the wider society can be also discerned in the academy.” Their argument is that the academic elite tends to be dominated by “white males.” Numerus American and British studies in the field of Higher Education (HE) have demonstrated that non-white academic staff often have short-term contracts and part-time work and are employed in small universities with lower status. Because of these circumstances, they tend to have lower positions and wages than “white” academics (see, for example, Fenton et al. 2000; Carter 2003; Tuitt et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2008; Sang et al. 2013; Alexander and Arday 2015). What is being demonstrated in these studies is how “people of color” are excluded from networks of academics who write research applications and receive research funding. They do not have the support of a powerful mentor and are referred to less prestigious subjects for teaching.

There are similarities between the labor market situation of young people of native background and that of individuals of migrant background since both groups are “newcomers in the field”. The similarity is more apparent when individuals try to enter the labor market to get their first job. Many young people of native background may not have the sufficient and adequate contacts from whom to obtain information and support when applying for a position. However, when young people of native background and individuals of migrant background finally are recruited, their career paths do not follow the same pattern. One reason is the well-known preference for similarity in social relations or the “homophily principle,” which means that interactions usually occur between actors with similar resources and lifestyles (Lin and Erickson 2008, Behtoui and Neergaard 2010). In addition to social class (as a determinant of the quality of resources in one’s network), Lin and Erickson (2008) point to gender and race/ethnicity as also being decisive features. So as long as the stratification system is gendered and racialized, social networks—formed largely on the homophily principle—will continue to be gendered and racialized as well.

As Mählck (2013: 66) argues, despite extensive data collection and research on unemployment, dependence on social welfare, crime, poverty, and violence among immigrants and their descendants, “there is an almost complete discursive silence” with regard to the “stranger” in the Swedish academy. One reason could be that not much time has passed since non-white academics started entering into Swedish universities.

This paper is about immigrants in Swedish HE, which provides an interesting case for a number of reasons. As Pinheiro et al. (2014: 234) underline, the Swedish HE system “ha[s] traditionally been characterized by the presence of a rather powerful nation-state, and a strong emphasis on access (equality of opportunity) and regional policy considerations.” With its close connections to a long tradition of social democratic structures and cultural norms and values, “aspects such as horizontal differentiation, inter- and intra-institutional collaboration and equalitarian dimensions have traditionally played a stronger role when compared to vertical forms of differentiation, meritocratic behaviour and competition within and across academic groups and institutions.” Moreover, as a small European country, Sweden’s economy is highly dependent on its intensive interaction with the international marketplace all the while coming up against more and more competitors on all sides. The resources that traditionally have been important sources of Swedish comparative advantage are those of human, physical, and knowledge capital (Learner and Lundborg 1997). Hence, attracting the best international PhD students and researchers has been considered as a vital ingredient for the long-term economic development of the country.

The Swedish HE system includes 16 public universities and 20 public university colleges, in addition to a handful of independent institutions (all relatively small). Irrespective of their size, specialization etc., all HE institutions adhere to the same law (the 1994 Higher Education Act and Higher Education Ordinance).

Using quantitative descriptive methods and qualitative interview material, this paper examines whether and how factors other than academic qualifications (such as gender and ethnicity) may be of importance for “others” when they attempt to make a career within Swedish academia. We have applied a mixed-method approach (see Creswell 2013). Combining qualitative and quantitative data has allowed us to expand the breadth of the study and offer a more complete account of the “how” factors that may have importance in the shaping of an academic career.

The first section of this paper is based on the analysis of register data from Statistics Sweden’s LISA database 2012. Only individuals who had a PhD (from Sweden or abroad) and that had a Swedish university or university college as their latest employer are included in our analysis—a total of 15,953 persons (for detailed information about these data see also Behtoui 2017). These individuals hold different positions. Some of them have scientific positions (as post-docs, researchers, lecturers, associate professors), and others have bureaucratic-academic positions (as departmental heads or deans of faculty) in their universities.

The material for the second part of the article consists of semi-structured qualitative interviews with 19 academics of migrant background. The academics had their background from the same Asian country, with just one individual from another Asian country.Footnote 1 Most of the informants came to Sweden during the 1980s, with the exception of four individuals who arrived as exchange students in the 1970s. A majority of the interviewed were from highly educated middle-class backgrounds in their country of origin and had thus not experienced social (upward) mobility in the traditional sense of the term. The age of the informants ranged from 48 to 62, with the majority in their mid- to late 50s. They represent the humanities, the social sciences, medicine, technology, and informatics. At the time of their interview, all except three individuals were in fixed employment as either full or associate professors at a Swedish university or university college. These include major universities such as Stockholm and Uppsala as well as less prestigious university colleges. The interviews took place at the respondent’s workplace, were digitally recorded and transcribed, and the topics covered were their backgrounds, migration narratives, and the pathway to—and experiences of—working in HE in Sweden. For this article, we thematized and analyzed the material by looking particularly at educational pathways, networks, and mentorship, as well as the respondents’ personal experiences of processes of inclusion and exclusion.

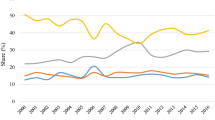

The migrant background in Swedish academia: an overview

Our quantitative sample is made up of around 59% men and 41% women, of whom about 80.5% were of Swedish background (born in Sweden, with one or two Swedish-born parent—our reference group). As the share of the total population of Sweden of individuals from this latter category in 2012 was 75%, we can see that their rate among academics was 5.5% higher than their share of the total population. If we separate our data into countries (see Table 1), individuals from China, followed by Germany and Iran, had the highest number of academics in Sweden after our reference group. Academics born in Eastern European countries (3.6%) and Western Europe and North America (3.5%) make up the largest share of non-natives in Swedish universities. Among those who were born in Sweden of two foreign-born parents (the immigrant “second generation”), there were more children of Nordic and Eastern European (North_2 and East_2) background than from other world regions.

The share of academics born in Africa, Asia, and South America is proportionally higher within small university colleges. The number of PhDs who were employed at the time of our study is greatest among individuals from the majority population (97%) and lowest among those born in Africa or China (84%). The average income for those who are working is higher for those born in Sweden with at least one Swedish-born parent (our reference group), compared to those born in Africa, Asia, or Latin America.

To distinguish those who, at the time of our study, responded “Have a job,” we have used the “Yrkesställning” variable from the LISA database. This information is sent by employers to the tax authorities in November each year. It is, perhaps, worth mentioning that, if some of the individuals in our study had been unemployed at the time of interview, then the university had been their last workplace (before becoming unemployed). In the sample, there were 933 people who had no employment, although it is probable that some of them have left Sweden. Therefore, only those who had a disposable income of over 100 thousand SEK (10,000 Euro) were selected for our analysis regarding employment. On the basis of this information, a dummy variable was created that gets the value of 1 if the individual has employment (15,020 people) and of zero if this is not the case (337 persons).

In order to examine the factors which affect the probability of finding employment after completing a PhD, we used a logistical regression with “Have a job” = 1 as our outcome variable. The result in model 1 of Table 2 shows that, as age increases, so does the probability of being employed. Other variables in model 1 (gender and number of years after completion of a PhD) had no significant effect in that regard. In model 2, we have added variables indicating migrant background (with Swedish-born individuals with at least one Swedish-born parent as the reference group). Compared to this latter, academics born outside Sweden and the children of Eastern European immigrants had less probability of being employed at the time of our study. The situation was the worst for individuals from Africa, Asia, and Latin America who, compared to the reference group, had 70–85% lower odds of being employed. In model 3, we have included three new variables, depending on whether individuals (i) gained their PhD in Sweden, (ii) were Swedish citizens, and (iii) had lived in Sweden for more than 10 years. The results show that those who have a PhD from Sweden (compared with those who completed their doctorate abroad) have 84% greater odds of having employment. The effects of the two other variables (having lived longer than 10 years in Sweden and being a Swedish citizen) are, however, not statistically significant. Through the inclusion of these three variables, the gap decreases between those with an immigrant background and the reference group.

In the next step, we studied the career positions of those who were employed. From a total of 15,616 individuals, we selected only the 15,020 who had a job. In the dataset used for this study, there is no information on whether individuals have a permanent or a temporary position or whether they work full- or part-time. Furthermore, it gives no detailed information about their formal status within the workplace hierarchy—for example, whether they have scientific positions (as post-docs, researchers, lecturers, associate professors) or bureaucratic-academic positions (as departmental heads or deans of faculty). We do, however, have information about their salaries (based on tax records), which we are assuming to be a proper indicator for the place of each individual within the organizational hierarchy (whether these are higher scientific or higher bureaucratic-academic positions). The income provides, in fact, more detailed information about individuals’ positions in the workplace because, within the university sector, the variation of positions are limited (for instance, post-docs, lecturer, associate professor, and professor) and we know that promotions within the university ranking system take a range of different forms that are not necessarily reflected in these few positions.

We have transformed individuals’ annual incomes into natural logarithm (LN) income in order to obtain a direct interpretation in terms of elasticity (differences in percentages instead of in SEK).

In model 1 of Table 3, we see that the effect of “age” (indicating the total work experience) and number of “years after doctoral graduation” (indicating the specific work experience within the academic environment) are positive and significant, which means that, for each year of age, the annual income rises by 1% and, with each additional year after graduation, by 3%. The significant and positive coefficient for the gender variable shows that to be male (compared to female) is associated with a 7% higher income.

Model 2 includes migration-background variables. The results show that nearly all academics who are born abroad have a lower income (an indication of lower status within the hierarchy) compared to our reference group.

The results in model 3 show that having Swedish citizenship and living in the country for more than 10 years increase annual income (by 16 and 13%, respectively) but the effect of having gained an academic qualification in Sweden (compared to abroad) is not statistically significant. Controlling for the three variables in model 3 (as a proxy for access to greater social capital) decreases the gap between academics from Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America (by between 4 and 10%) compared to model 2. This means that access to greater social capital has a positive impact on an individual’s position within Swedish academia.

Finally, as the results in model 4 show, those who have a degree in the humanities, the natural sciences, information technology, or agriculture had a lower income than those who had a degree in medicine. We have also included in the model the variable “Work in small universities,” which indicates that the annual income of academics employed there (their likelihood of promotion) is around 4% lower than those working within large universities.

Even after including all these control variables, there are still considerable differences between the annual incomes of academics born in Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America on the one hand and the reference group on the other (between 20 and 30% less for the former). There is no significant difference between the reference group’s income and that of academics born in Sweden of parents born in other Nordic countries, Western Europe, and North America. The career possibilities for academics in the first group (Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America) are thus fewer than for all other categories, even after taking into consideration the individual’s work experience, gender, social capital, discipline, and university in which they work.

The recruitment and promotion of “others”

Bourdieu (1996: 39) argues that an individual’s social background—such as class, gender, and race/ethnicity—is of considerable consequence for the position attainable within academia: “Social origins have their impact, although they are never taken as such to form a basis for judgement” (Bourdieu 1996: 214). The results of our quantitative data analysis reveal that an individual’s background (e.g., gender and migration history) is significantly associated with his or her position.Footnote 2 So how do these processes look like in practice?

A female researcher in the humanities told us:

To enter a PhD program during the latter part of the 1990s and thereafter was an incredibly hard struggle. You needed to know the system very well to manage the hard competition, write a good Master’s thesis, an excellent research plan and a personal letter… For a lot of immigrants who lacked this knowledge and these contacts it was very hard.

As early as the 1980s and early 1990s, at a time when getting a scholarship was relatively easier than today, some of our respondents were admitted as PhD students. However, as one lecturer in the social sciences says, during that time, there were obvious A, B, and C groups among the doctoral students:

The A group consisted of those few who had been admitted to the supervisor’s research project and received a salary from the start. Then there was a group of doctoral students who partly took out student loans and partly worked within the department for the first two years. The worst-off were those, like myself, who worked outside [the university] to support my family – I was a cleaner for the first two years. Of course, I took all my courses and read but I didn’t have time to hang around and drink coffee and take part in the coffee-room discussions.

These coffee-room discussions can be important as an informal forum for exchanging information and for networking. A female professor in the humanities says about her period as a doctoral student:

We foreign PhD students had our own little group, had fun with each other, worked hard..., but we didn’t even have a room in the same house as the others…we felt like a lump outside the faculty…and it felt – to be honest – better, since we didn’t talk Swedish very well. We felt inferior all the time, because in humanistic departments, Swedish language is the language of the seminars.

Previous research has shown that, besides the formal courses that PhD candidates follow, there is also a hidden curriculum which, through socialization processes, educates them in the norms, values, and principles of the academic world. As Acker (2001: 62) highlights, doctoral students who enter graduate school learn two aspects of socialization. Firstly, the conventions of the discipline—when the students “are being socialized or ‘disciplined’ into a research culture.” They learn the habitus of a particular field in which they hope to become sociologists or biologists. Secondly, they should learn the organizational culture of the department or departmental practices, which are more or less similar to politics. This hidden curriculum is embedded “within the deepest level of the iceberg” (2001: 62). Some students are successful in getting to grips with this curriculum. They understand what is required to be a successful graduate student and to plan their future career, while others constantly struggle. Such discursive practices validate certain experiences and explain others as illegitimate. It is through familiarity with this hidden curriculum that the doctoral student can be included in groups that write research proposals and make careers within academia.

One female associate professor in the social sciences says the following about knowing the codes of the academic environment:

I had these kinds of problem when starting my PhD studies (…) during a course on quantitative methods I asked an influential professor in the department, who taught the course: “Is the world really so logically constructed that we can understand it with the help of numeral logics?”. The professor got extremely annoyed by what I said and from then on, he discouraged me as much as he could. My lesson from this episode was to respect codes of conduct very carefully.

Many respondents emphasized the importance of having an extensive social network both within and outside the department, with other doctoral students as well as with senior researchers. According to Bourdieu (1996: 3), relations such as these are decisive if a person wishes to make a career within academia. The most important of all, Bourdieu writes, is to have an influential supervisor or mentor and, through her or him, become a member of resourceful networks which, in turn, open up opportunities to be involved in joint research applications and to participate in qualifying teaching assignments. A researcher in the social sciences says the following about the weight which is attached to the “choice” of a powerful supervisor:

I was lucky because my supervisor was a nice young left-wing person who encouraged me the whole way, from my enrolment for a Bachelor’s and then a Master’s degree to her encouraging me to apply for doctoral study. However, it was bad luck at the same time because she was pretty marginal in the department and not part of the powerful group who were all quantitative researchers. They did not like my supervisor and her students (…) what we did was not real science, but “politics” or “literature” (…) and, after I graduated, my supervisor went on sick leave because the environment made her unwell.

Another female social scientist, who has still not been able to secure a permanent position 10 years after finishing her PhD, shares the same experience:

During my Master’s studies I got in touch with an associate professor who was left-wing and who helped me a lot. I adjusted the topic of my Master’s dissertation to fit with his research project and to be able to continue as a doctoral student.

Nevertheless, when her mentor’s career went downhill, it also became hard for her as a doctoral student. A male professor in pedagogy talks about his ex-supervisor in the following way:

When I was a doctoral student, my supervisor was an overlooked associate professor. However, luckily enough, before I graduated, he became professor at two universities and was involved in building up a research centre. They wanted to recruit a number of young researchers and the supervisor offered me – who had a thesis with the right profile – a job at his new location.

What these citations underline is the importance of a powerful supervisor not only for access to academia but also for possibilities for a continuing career. For individuals with migrant backgrounds who often lack extensive networks, such mentorship can play an even more crucial role than for other young academics.

Difficulties and survival in academia

The new doctoral student is socialized into the environment of senior researchers within the department through learning its norms and codes (see, for instance, Trower and Chait 2002). However, both previous research and our interviews show that doctoral students of minority background are at risk of being socially isolated and experiencing a cold environment, prejudice, and sometimes hostility (Law et al. 2004). “One of my closest friends terminated his doctoral studies and left with a licentiate degree because he couldn’t take the excluding environment of the department,” says a social science researcher we interviewed, adding that the isolation was unbearable for his friend.

Lee and Rice (2007: 381), reporting on the experiences of international graduate students from the global South in US universities, write: “We consider a range of difficulties they encounter which runs from perceptions of unfairness and inhospitability to cultural intolerance and confrontation.” Other studies in this field describe a more subtle form of marginalization rather than the direct discrimination of non-whites (Teranishi and Briscoe 2007). As reported in these studies, “people of colour” have been excluded from networks of academics who write research proposals, nor do they receive support from their supervisors after graduation. One female researcher in medicine whom we interviewed said: “Powerful people in academia look for someone who is similar to themselves, both in terms of interest and lots of other things, and we don’t fulfil their requirements in many regards.”

In order to understand how recruitment processes within academia take place, Nielsen (2016) uses the concept of “hidden recruitment.” Some positions within higher education are appointed without any form of open competition (closed procedures). One end result can be that those who have insufficient network ties in the established academic environment are excluded. Sometimes, competition is avoided by framing a job profile so that very few (or occasionally only the institution’s pre-selected) candidates can be considered appropriate for the position to be filled. These kinds of tailored advertisement are used to avoid the potential risk of having to recruit “outsiders.” Social similarities along dimensions such as race, gender, and ethnicity in the academic world (as in other fields) structure a range of social network relations that reproduce patterns of social inequality and disadvantage those who do not have access to these networks (Schoug 2004). Even formal appointment procedures can become biased through the selection of the “right” external experts. Finally, it is possible to correct the process of recruitment with campus recruitment interviews to exclude “outsiders.” As one female researcher told us:

There were two lectureships that had been announced. For one of them they appointed an “insider” who had been ranked first. For the other position, I was ranked first by all three external experts, who were big names in our discipline. However, the department heads invited the three top candidates for a recruitment interview and to give a lecture. I suspected the process wasn’t “clean”, but told myself not to be cynical. What happened was that they appointed another “inside” candidate, a Swede who had worked there before, but who had been ranked as number three by all the experts. Most people around me told me to keep a low profile and not protest because it doesn’t lead anywhere.

A researcher in medicine said: “For one professorship they ranked an immigrant number one and then me. But they withdrew the position without any explanation.” Another researcher in a medical discipline said more carefully:

I don’t want to generalize but, if I look around me and at myself, it is like someone sets a stop in front of you when you reach a certain level, and you need to be grateful because you’re an immigrant. You need to be grateful for your job, for what you have today.

To obtain prestigious assignments in academia, like that of editor of a scientific journal, examiner of a doctoral thesis, supervisor for new doctoral students, lecturer on PhD courses, and other commitments that prepare you for higher positions (those of associate professor and professor), you need powerful and already established contacts who can recommend you: “But often it isn’t us immigrants who are recommended,” one female researcher said.

That subtle mechanisms are at work which prevent the “stranger” (Simmel 1950) from achieving senior academic positions does not mean that open forms of discrimination do not occur. One story comes from a male associate professor. When he was a third-year doctoral student, he applied for a scholarship that would give him the possibility of spending a term at a university abroad. Another doctoral student of Swedish background who had recently been employed was his competitor. “I was much more qualified than he was for the scholarship, but he got it anyway and I, with great frustration, asked all the time ‘WHY?’”. When he wrote a letter of protest to the head of department, he was told that he had forgotten to submit a necessary document – “Which was bullshit, because I had”. He continues: “It is possible that individuals with a Swedish background are surprised to hear these kinds of stories, but it is our reality.”

Our material also supports what has been found in the American context regarding the forms of “subtle” discrimination mechanisms (Teranishi and Briscoe 2007). One of the interviewed associate professors in the field of medicine suitably framed this as a “discrete discrimination” that also takes place through formal processes such as recruitment and job announcements. In the next section, we move from these processes of discrimination to briefly touch upon the door-openers and possibilities that can be linked to a migrant background in academia.

Specific subfields and other door-openers

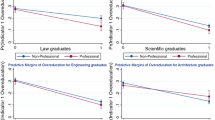

As Bourdieu maintains (1996: 48–49), the university field is organized according to diverse principles. There can we find the “dominant pole of the academic field” and “the subordinate pole.” Who you are (gender, social origin, race, and ethnicity) may affect your likelihood of promotion to different degrees in the various poles of the academic system. Time and space are certainly crucial in defining these poles. As our quantitative data (presented in Table 4) show, academics with roots in Eastern Europe, Asia, and African countries are over-represented within medicine, technology, IT, and the natural sciences and clearly underrepresented within pedagogy and the human and social sciences.

One reason for over-representation within medicine, technology, IT, and the natural sciences could be the favorable labor market conditions and high salaries for people with a university degree within these disciplines.Footnote 3 Technological fields like computer science and engineering, together with medicine, are high-demand fields outside academia. With an engineering degree, for example, one can earn a significantly higher salary on the regular labor market than someone who stays in academe and goes on to study for a PhD (see the wage statistics of the Swedish Confederation of Professional Associations or SACO). Furthermore, the probability of landing a permanent job with favorable promotion opportunities is also higher. This means that there is a disparity between academia’s demand to recruit PhD candidates in disciplines like IT and technology and the supply of native Swedes who are willing to dedicate themselves to research in these fields. These factors open up possibilities for the foreign-born to apply for PhD positions in these disciplines.

Several academics who, today, work within technology and medicine, described how they found it “easy” to succeed in subjects such as physics and mathematics, subjects which, according to many others, were seen as “tough.” One professor argued that his good knowledge of English compensated for his weak knowledge of the Swedish language as, within technology and the natural sciences, Swedish language skills are less important than in other subjects: “The advantage of these technical subjects is that you do not need to know as much Swedish.” According to him, during the late 1980s and early 1990s, more than 30% of his fellow students came from the same country as he himself did. Now, as a professor and co-responsible for the admittance of students and post-docs, he sees a similar situation—“It’s so international that the language here is mainly English.”

These successful academics of migrant background have become door-openers for a younger generation of researchers. One of our respondents told us that, when the most recent post-doc position was advertised, 70–80% of the applicants came from the same country as the professor’s own country of origin. When a national group is established, they can use social networks to help others of similar origin to apply and make a career in the same establishment.

As far as language acquisition in HE is concerned, as Kuteeva and Airey (2014: 534) write, English has been widely used as a language of research and publication in Swedish universities since the Second World War. However the use of English in Swedish universities in recent years has risen to the extent that “warning voices have been raised about the marginalization of Swedish as an academic language.” As an indication of this trend, they mention that around 95% of all dissertations in subjects such as medicine, industry and technology and computer and natural sciences at Swedish universities are currently written in English. Hence, even if knowledge of the Swedish language seems to be a minor problem in these subjects for academics with an immigrant background, it is still important for those working in the field of humanities and social sciences as a means of communication.

Positions on the periphery

That academics with a migrant background often work at small universities in lower-status positions and salaries than “white” academics has already been documented in American and British studies (see Fenton et al. 2000; Carter 2003; Tuitt et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2008; Sang et al. 2013; Alexander and Arday 2015).

According to one informant (a researcher in the humanities), it is easier for migrant academics to find a position in “newer” university colleges than in old and established ones…

…because, if you disregard status, the new seats of learning are more like an open field. In the same way it is easier [the researcher argues] to enter newer subjects such as social work than the older and more-established disciplines such as philosophy and law, where you can find researchers with parents (and sometimes grandparents) who were also academics.

Several of our informants have permanent positions at smaller universities outside the large academic centers of Stockholm, Gothenburg, Lund, and Uppsala. A female medical scientist reported how the position she applied for at a larger Swedish university was withdrawn the three times when she was ranked in first place. Our interview material shows that several academics of migrant origin express frustration at what they see as difficulties in their work at the high-status educational and research establishments in Sweden. In most cases, the interviewees saw their permanent positions at smaller university colleges in regional areas as a second-best choice. However, they emphasized that they actually feel happier in their present workplaces, since they have more colleagues with similar backgrounds.

Apart from the positions on the periphery that our quantitative data and the interviews highlight, several of our informants raised the issue of topics on the periphery or the ethnic niches available for academics of migrant origin (Puwar 2004a). According to their statements, there are many such members of faculty who are working in areas related to topics such as migration, minorities, diversity, immigration, and integration who thus become “race or ethnicity specialists.” This is the case not only in the socio-humanistic disciplines or pedagogy but also within medicine, where some of our informants are researching immigrant health. Answering a question about the consequences that the choice of these topics might have for a person’s position and career within academia, one medical researcher said: “For the last 10 years I’ve focused on immigrant health. I’ve applied and applied and never received any funding. Last year was the first time I succeeded.” Besides the fluctuating possibilities for funding (based on the actuality of the research topic), another issue was the internal status of the subject. A female associate professor in the social sciences recounted the following:

A colleague once told me that if you go to sociological conferences, the seminars that deal with welfare, stratification and class are the ones with the highest status, while those on immigration and integration have the lowest. Then I thought, maybe that is why we are pushed into these kinds of topics.

A marginal elite?

In this article, we have told the story of a group of academics who, up until now, have been invisible in previous research on Swedish academia. Our descriptive data show that the presence of academics of migrant background among the academic elite is far from negligible. However, there are also important differences between the social sciences and the humanities on the one hand, and the natural sciences and technology studies on the other, regarding the number and positions of such migrant-origin academics.

The qualitative interview material offers a complementary and nuanced account of the “how” mechanisms that are central in the processes of shaping the actual careers of some of these migrant-origin academics. The material from these interviews points to the following central insights

-

First, the importance of mentorship and the role of the powerful and resourceful supervisor. For academics with migrant backgrounds who lack extensive social networks, such mentorship has a crucial role compared to other newcomers in academia.

-

Second, there are huge differences in how an academic career is made possible, perceived, and experienced depending on the academic sub-field. Technical subjects and the natural sciences have more open doors for migrant-origin academics in Sweden. This international environment makes academic survival easier in terms of, for instance, the use of the English language in the workplace. Swedish language is still important for those working in the field of humanities and the social sciences as a means of communication and teaching.

-

Third, the acts of “subtle” marginalization (Teranishi and Briscoe 2007) take place in different forms and across academic disciplines—through construction of the formal processes of job announcements, recruitment, and promotion which potentially favor “insiders,” through including “white academics” in the powerful social networks, through the exclusion of “strangers” and even direct discrimination against “outsiders” and, finally, through pushing academics with a migrant background into the peripheries of the various academic fields.

As Henry and Tator (2009) state, the disparity of power between the different groups in the university context is not a consequence of isolated cases of discrimination but mainly the result of an invisible system that leads to certain people having more power. Puwar (2004b: 56) also emphasizes that the dominant position of some groups is mainly due to their historical privileged place in HE, their strong and resourceful networks, and their knowledge of the subtle rules of the game regarding the work environment and social relations. “So people who don’t quite know how to play the game or obtain the endorsement of significant peers” are not able to rise in the hierarchy (Puwar 2004b: 56).

In spite of their marginal positions, the very presence of individuals of migrant background in academia and their increasing numbers in recent decades have an effect on the environment. This presence may facilitate life for racialized university students and open doors for coming generations of other migrant-origin and international academics in Sweden. Greater demand for qualified international academics certainly makes this process easier and swifter.

Writing about France, Bourdieu (1996: xviii) argues that intellectual heroes like Althusser, Barthes, Deleuze, Derrida, and Foucault all “held marginal positions in the university system”; they were “deprived of the power and privileges” of becoming an “ordinary professor.” Their marginal position may have led the holders to be inclined to be in a sort of “anti-institutional mood” which encouraged them to uncover the social processes that maintain the established order and marginalize them, to take sides and feel sympathy with other marginal groups, both within academia and in society in general (1996: xviii).

The rich intellectual tradition of Simmel, Schutz, and Coser also highlights the creativity of academics on the margins. As McLaughlin (2001: 271) states: “Strangers, marginal men and marginalized women” have sometimes been able to bring new ideas into the academic world that are less likely to be produced by individuals with powerful positions.

Notes

The names of these countries are anonymized in order to protect the integrity of the informants.

Female academics (compared with their male colleagues), after control for merit-related variables, had a 9.4% lower income (fewer possibilities for advancing within Swedish academia); see Table 3, model 4.

The timing (business cycles), as mentioned, is critical to the possibilities of recruitment of graduates from different academic disciplines on the labor market.

References

Acker, S. (2001). The hidden curriculum of dissertation advising. In E. Margolis (Ed.), The hidden curriculum in higher education (pp. 61–77). New York: Routledge.

Alexander, C., & Arday, J. (2015). Aiming higher: race, inequality and diversity in the academy. London: Runnymede Trust & London School of Economics.

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic tribes and territories : intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines (2. ed.). Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Behtoui, A. (2017). “Främlingen” Bland Svensk “Homo Academicus”. Sociologisk Forskning, 54(1), 91–110.

Behtoui, A., & Neergaard, A. (2010). Social capital and wage differentials between immigrants and natives. Work, Employment and Society, 24(4), 761–779.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). Homo Academicus. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Carter, J. (2003). Ethnicity, exclusion, and the workplace. Houndmills and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Fenton, S., Carter, J., & Modood T. (2000). Ethnicity and academia: closure models, racism models and market models. Sociological Research Online 5: http://www.scoresonline.org.uk/5/2/fenton.html.

Henry, F., & Tator, C. (2009). Racism in the Canadian University: demanding social justice, inclusion, and equity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Kuteeva, M., & Airey, J. (2014). Disciplinary differences in the use of English in higher education: reflections on recent language policy developments. Higher Education, 67(7), 533–549.

Law, I., Phillips, D., & Turney, L. (2004). Institutional racism in higher education. Stoke-on-Trent and Sterling: Trentham Books.

Learner, E. E., & Lundborg, P. (1997). A Heckscher-Ohlin view of Sweden competing in the global marketplace. In R. B. Freeman, B. Swedenborg, & R. Topel (Eds.), The welfare state in transition: Reforming the Swedish model (pp. 399–464). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, J. J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53(3), 381–409.

Lin, N., & Erickson, B. H. (2008). Social capital: an international research program. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mählck, P. (2013). Academic women with migrant background in the global knowledge economy: bodies, hierarchies and resistance. Women's Studies International Forum, 36, 65–74.

McLaughlin, N. (2001). Optimal marginality: innovation and orthodoxy in Fromm’s revision of psychoanalysis. The Sociological Quarterly, 42(2), 271–288.

Nielsen, M. W. (2016). Limits to meritocracy? Gender in academic recruitment and promotion processes. Science and Public Policy, 43(3), 386–399.

Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L., & Aarrevaara, T. (2014). Nested tensions and interwoven dilemmas in higher education: the view from the Nordic countries. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 7(2), 233–250.

Puwar, N. (2004a). Space invaders: race, gender and bodies out of place. Oxford: Berg.

Puwar, N. (2004b). Fish in and out of water: a theoretical framework for race and the space of academia. In I. Law, D. Phillips, & L. Turney (Eds.), Institutional racism in higher education (pp. 49–58). Stoke-on-Trent and Sterling: Trentham Books.

Sang, K., Al-Dajani, H., & Özbilgin, M. (2013). Frayed careers of migrant female professors in British academia: an intersectional perspective. Gender, Work and Organization, 20(2), 158–171.

Schoug, F. (2004). På Trappans Första Steg. Doktoranders och Nydisputerade Forskares Erfarenheter av Akademin. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Simmel, G. (1950). The stranger. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited and translated by Kurt Heinrich Wolff, 402–408. New York: The Free Press.

Teranishi, R., & Briscoe, K. (2007). Social capital and the racial stratification of college opportunity. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 591–614). Dordrecht: Springer.

Trower, C. A., & Chait, R. P. (2002). Faculty diversity: too little for too long. Harvard Magazine, 104(4), 33–37.

Tuitt, F. A., Sagaria, M. A. D., & Turner, C. S. V. (2007). Signals and strategies in hiring faculty of color. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, Vol. 22 (pp. 497–535). Dordrecht: Springer.

Turner, C. S. V., González, J. C., & Luke Wood, J. (2008). Faculty of color in academe: what 20 years of literature tells us. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(3), 139–168.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Marianne & Marcus Wallenberg Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Behtoui, A., Leivestad, H.H. The “stranger” among Swedish “homo academicus”. High Educ 77, 213–228 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0266-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0266-x