Abstract

While stigmatisation is universal, stigma research in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is limited. LMIC stigma research predominantly concerns health-related stigma, primarily regarding HIV/AIDS or mental illness from an adult perspective. While there are commonalities in stigmatisation, there are also contextual differences. The aim of this study in DR Congo (DRC), as a formative part in the development of a common stigma reduction intervention, was to gain insight into the commonalities and differences of stigma drivers (triggers of stigmatisation), facilitators (factors positively or negatively influencing stigmatisation), and manifestations (practices and experiences of stigmatisation) with regard to three populations: unmarried mothers, children formerly associated with armed forces and groups (CAAFAG), and an indigenous population. Group exercises, in which participants reacted to statements and substantiated their reactions, were held with the ‘general population’ (15 exercises, n = 70) and ‘populations experiencing stigma’ (10 exercises, n = 48). Data was transcribed and translated, and coded in Nvivo12. We conducted framework analysis. There were two drivers mentioned across the three populations: perceived danger was the most prominent driver, followed by perceived low value of the population experiencing stigma. There were five shared facilitators, with livelihood and personal benefit the most comparable across the populations. Connection to family or leaders received mixed reactions. If unmarried mothers and CAAFAG were perceived to have taken advice from the general population and changed their stereotyped behaviour this also featured as a facilitator. Stigma manifested itself for the three populations at family, community, leaders and services level, with participation restrictions, differential treatment, anticipated stigma and feelings of scapegoating. Stereotyping was common, with different stereotypes regarding the three populations. Although stigmatisation was persistent, positive interactions between the general population and populations experiencing stigma were shared as well. This study demonstrated utility of a health-related stigma and discrimination framework and a participatory exercise for understanding non-health related stigmatisation. Results are consistent with other studies regarding these populations in other contexts. This study identified commonalities between drivers, facilitators and manifestations—albeit with population-specific factors. Contextual information seems helpful in proposing strategy components for stigma reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Stigmatisation is a universal process where specific individuals or groups are labelled, attributed stereotypes, and separated between “us” and “them”, leading to status loss and devaluation, and discrimination (Link and Phelan 2001). It essentially has three overarching functions; to keep people in through social norms enforcement; away to avoid disease transmission; or down to dominate and exploit (Phelan et al. 2008; Bos et al. 2013). Stigma has recently been further deconstructed by Stangl and colleagues (2019) in the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework. Drivers, which are always negative perceptions and beliefs that catalyse and trigger stigmatisation, are one component. Examples are fear and perceived danger, perceived responsibility and perceived origin (Jones 1984; Stangl et al. 2019). Facilitators are another factor, which can both intensify and mitigate stigmatisation, but are not the cause of the specific stigmatisation itself. These can be socio-economic status, religion and local policies, amongst others. Together they determine the actual stigma ‘marking’, or attaching a label, after which stigmatisation will, according to this conceptualization, manifest itself. These manifestations are demonstrated in experiences and practices of stigma such as differential treatment, restricted participation, violence and neglect – with negative impact upon quality of life (Stangl et al. 2019). It has been concluded that there are more similarities than differences between the drivers and manifestations in different stigmatisation processes (Nayar et al. 2014). However, research has indicated that contextual information is required to make stigma reduction interventions effective (Bos et al. 2008).

So far, stigma reduction work, under-researched in itself (Pescosolido and Martin 2015), has focused mostly on health-related stigma in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). A recent systematic review, investigating implementation science and health-related stigma reduction interventions in LMIC, included 35 studies and excluded eight studies as they targeted non-health-related stigma, as sexual orientation and sex work (Kemp et al. 2019). HIV/AIDS stigma was the most researched or addressed stigma in LMIC, followed by mental health stigma (Cross et al. 2011; Kane et al. 2019; Rao et al. 2019).

While 90% of the world’s children and adolescents live in LMIC (Kieling et al. 2011), stigma research has prioritised adults, and rarely integrated the perspective of children and adolescents (Chambers et al. 2015; Kane et al. 2019) or targeted children in interventions (Hartog et al. 2019). Children however have unique stigmatisation risks, given their lower social status compared to adults in many LMIC (Mukolo et al. 2010).

To our knowledge, twenty-three studies specifically researching stigma in DR Congo (DRC) have been published. Twenty-one have concentrated on sex-related stigma, such as female survivors of stigma concerning sexual violence (Greiner et al. 2014; Verelst et al. 2014; Babalola et al. 2015; Scott et al. 2015; Murray et al. 2018a, b; Wachter et al. 2018) and male survivors, (Christian et al. 2011), and HIV (Newman et al. 2012; Musumari and Feldman 2013; Gebremedhin and Tesfamariam 2017; Tshingani et al. 2017; Venables et al. 2019). Other studies have discussed stigma related to intimate partner violence (Kohli et al. 2015; Glass et al. 2018), abortion (Casey et al. 2019; Steven et al. 2019), syphilis (Nkamba et al. 2017), fistula (Young-Lin et al. 2015) and contraception-use (Muanda et al. 2018). A large-scale DRC-based study on maternal-child relationships of children born out of sexual violence indicated the need for interventions to reduce stigma and increase acceptance for children conceived from sexual violence and their mothers alike (Rouhani et al. 2015).

This study aims to gain insight into the commonalities and differences of stigmatisation of three different populations experiencing non-health related stigma by looking at drivers, facilitators and manifestations of stigmatisation, following the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework. It is part of a formative process to the develop and evaluate a stigma reduction intervention which intends to be applicable in multiple settings and for multiple stigmas. This intervention in development builds on the conclusion that to strengthen stigma reduction initiatives, we need to go beyond condition-specific stigma silos (Brakel et al. 2019) and learn from its resemblance in stigmatisation processes. It further aligns with the recommendation to have core, standardized intervention parts with guidance on contextual adaptation (Kemp et al. 2019). Furthermore, this study aims to add to the knowledge base of under-researched populations experiencing stigmatisation.

The three populations this study focused on were: (1) unmarried mothers; (2) children associated with armed forces and groups (CAAFAG), and; (3) an indigenous population. These populations were identified as experiencing stigmatisation by the commissioning NGO, based on their assessments.

While the majority of stigma studies in DRC have focused on sex-related stigma, to our knowledge stigmatisation of unmarried mothers, who have taken part in extramarital sex, has not been researched in DRC. In other settings the stigmatisation of single or teenage mothers has been studied, describing experiences of maltreatment, judgement, disrespect and shame (Bennett 2001; Houghton 2004; Amroussia et al. 2017) or feeling forced into abortion as single motherhood and children out-of-wedlock were felt to be greater sins than abortion (Bennett 2001).

DRC has also seen the recruitment of children into armed forces and groups (Mwandumba 2015). Three studies have researched the stigmatisation of CAAFAG, or more specifically girls associated with armed forces and groups in DRC. These studies have described social rejection, reference to addiction and ‘acting as if still in the army’ (Johannessen and Holgersen 2014), the name-calling and maltreatment of girls associated with armed forces and groups by neighbours, family and peers (Tonheim 2012) and the experiences of discriminatory treatment, challenges to return to former friendships, and consequences on marriage prospects (Tonheim 2014), amongst others. Studies in other countries have further described stigmatisation of CAAFAG, such as in Sierra Leone, where former child soldiers perceived discrimination which affected their mental health (Betancourt et al. 2010). In Burundi, a number of CAAFAG indicated that they felt stigmatized and perceived as having murdered and bringing havoc to local communities (Song et al. 2014), while in Nepal some former child soldiers were seen as impure and polluted (Kohrt et al. 2010; Kohrt et al. 2015).

The stigmatisation in DRC of indigenous populations, such as denial of rights of the Mbuti “Pygmies” over land and health care, has been described, alongside segregation and exploitation, amongst others (Kamuha 2013). Studies in other country settings, high-income and LMIC alike, have further elaborated upon social exclusion and discrimination of indigenous populations, such as in Cameroon (Carson et al. 2019), Guatemala (Cerón et al. 2016), Australia and South Africa (Bachmann and Frost 2015) and Canada (Reading et al. 2016; Thiessen 2016).

2 Methods and Procedures

2.1 Research Setting

The study was conducted in a village in Kalehe Territory, South Kivu, DRC. This village was selected based on the following criteria; accessibility, a relatively calm security situation, the presence of the three populations experiencing stigma and good working relations between the NGO and the community. The NGO identified the three populations experiencing stigma, based on their ongoing service delivery programme and assessments.

2.2 Research Design and Methods

For data collection on stigmatisation we used a qualitative design with two group exercises; one for the population experiencing stigma and one for the ‘general population’, the latter including pictorials (see supplementary material). The exercises were slightly adapted in questions and pictorials if used with adolescents. We developed, within the family of Focus Group Discussions, a more structured, therefore easier to facilitate participatory group exercise as reaction-based activity—from hereon called Reaction-Based Group Exercise (RBGE)—where participants were asked to first share their reaction: yes, maybe or no, and thereafter substantiate their reactions. Questions for the population experiencing stigma addressed their experience with local services, leaders, community meetings, associations and their family, informed by the socio-ecological model (Bronfenbrenner 1977), while each group from the general population was asked to react to questions concerning one of the pictorials of local situations of social distance, based on Bogardus’ social distance scale (Wark and Galliher 2007), such as being neighbours, greeting people, or doing (home)work together. The first question sought to discover if they could accept the situation in the picture with someone of their choosing; the second if they could accept that situation if that someone were to come from the specific population experiencing stigma, and; the third and fourth if connection of the population experiencing stigma to their family or local leaders was acceptable, respectively.

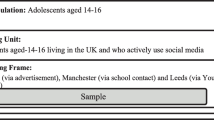

2.3 Study Population, Sample Size and Sampling

The population under study included everyone living in the village, either belonging to the populations experiencing stigma, or the general population. Men and women, adolescents and adults were represented. We intended to include 132 research participants, 72 from the general population and 60 from the populations experiencing stigma, evenly spread over men and women, adolescents and adults. Within the ‘unmarried mothers’ population experiencing stigma, we did have representation from children and adults, but due to the nature of the population there were no male participants. The participants were selected through purposive sampling.

2.4 Procedures

Twenty local research assistants followed a workshop [KH and a consultant] over a period of eight days concerning (1) understanding the research objectives; (2) stigmatisation; (3) research ethics, including child safeguarding, adverse events and informed consent, and; (4) data collection methods. Four teams, with two interviewers, a note-taker and a transcriber, collected data between 25 June and 12 July 2018, supported by four mobilisers to prepare potential groups and start the informed consent process. Two group reflection sessions were held to allow the research teams to reflect on the process, share their own experiences and improve data collection. A Child Protection Officer supported the research operations by supporting with communications and logistics, support the training as well as being on stand-by for adverse issues. RBGEs were conducted in the local language, either Kiswahili or Kinyarwanda. All RBGEs were audio-recorded and written notes were taken. At the end of each day the data was collected and securely kept [KH]. The transcribers listened to the audio in the local language, and translated the audio-text into written French. Their texts were randomly checked against the notes taken by the note-takers, and further checked on accuracy by another research team and adjusted where necessary. For seven RBGEs only the written data was used.

2.5 Data Analysis

Transcribed data, collected through RBGE, was coded and analysed through framework analysis [KH] in Nvivo12, based on a codebook informed by the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (Stangl et al. 2019), with as overarching topics stigma drivers, facilitators and manifestations.

2.6 Ethics

The ethical committee of the Université Libre de Pays des Grands Lacs (ULPGL) in Goma approved the research protocol on 12 June 2018. An informed consent process was conducted before participation. All participants provided written informed consent. Adolescents were asked for informed consent after their caregivers consented to their participation. Follow-up sessions were held with populations experiencing stigma to monitor for potential unintended negative consequences. No serious adverse events were reported.

3 Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

In total, twenty-five RBGE were conducted with three to five participants per group, fifteen with groups coming from the general population (n = 70) and ten from a population experiencing stigma (n = 48). The majority was female (54%, n = 64) and adult (65%, n = 77). In the general population, four groups discussed unmarried mothers, five CAAFAG, and six indigenous population. We had three groups of unmarried mothers, four groups of CAAFAG, and three groups of indigenous population discussing their experiences. See Table 1 for details.

The data was analysed based on the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework, focusing on three crucial elements to understand stigmatisation; (1) drivers that trigger stigmatisation, (2) facilitators that negatively or positively influence stigmatisation, and (3) manifestations of stigmatisation. Alongside these three main categories that were solicited during data collection, another category which merited attention emerged: (4) the outcomes of stigmatisation. Furthermore, a section on ‘positive community examples’ was added.

3.2 Theme 1: Stigma Drivers

Three drivers featured in the findings, namely perceived danger, perceived non-contribution or value, and perceived origin interlinked with immorality.

Perceived danger was considered the most prominent stigma driver for all three populations, by the general population and the populations experiencing stigma themselves. Regarding the three populations, there were various underlying perceptions that triggered the sense of danger, namely fear for behaviour transfer, for violence and impact on one’s life and livelihood, for social status loss, and of the unknown.

For both unmarried mothers and CAAFAG, perceived danger was generated by fear of behaviour transfer, i.e. becoming and acting like them. Girls, unmarried mothers themselves, indicated the challenge for other girls to associate with them as “those girls run the risk to be negatively influenced” because “they hang out with a prositute”. Other girls from the general population mentioned the fear of “being shown places to hunt [for men]”. CAAFAG shared perceptions on community opinions about them:“if you play with a bandit”—as CAAFAG were stereotyped—“you also become a bandit like him”.

Perceived danger was also triggered by fear of violence and for one’s life—a key concern regarding the indigenous population and CAAFAG. A boy from the general population mentioned that “if I would try [to play with a child from the indigenous population] I could die, those children can kill me”. CAAFAG indicated they were called “the community time bomb”. Participants indicated the military style remained with them after leaving the armed groups. One perceived his family was afraid of him, indicating “I will bring troubles (..) and that I can (…) go back to the armed group, and then return with the objective to hurt them”. An adult female participant from the general population further underlined negative perceptions of CAAFAG impacting on livelihood: “if a chicken enters his house, he could eat it”.

Other triggers underlying fear and perceived danger were loss of social status, or stigma by association, with men from the general population indicating that, if they were seen with unmarried mothers, they would run the risk of gossip: “if the boy that made her pregnant is from the same neighbourhood, the other boys fear being despised (..), because she is considered as left-over”. Girls from the general population feared losing husbands to unmarried mothers, and some indicated their fear for transfer of HIV. Fear of the unknown due to unfamiliarity in lifestyle was mentioned regarding the indigenous population.

Though perceived danger was most prominent, we identified two other drivers. Regarding all three populations, negative perceptions existed concerning their contribution and value. Unmarried mothers indicated they were called “kishosho”, or “without value”, “an idiot”. A participant shared the following about her family members: “they say that for the other girls they will be given cows [dowry], but what will I bring them?” A few male participants indicated unmarried mothers would invite other men into their households, bringing disruption, and that they would be asking for support for her children: “she will increase your burden”. While CAAFAG were seen as thieves and bandits, therefore taking from and not giving to the community, the value of the indigenous population was also questioned as a boy from the general population said: “they have no quality, nor intelligence”, and other participants cited their “inferiority complex”.

For unmarried mothers, how they became a mother outside of marriage, or the origin of their marking, also seemed to be important with regard to stigmatisation. ‘Pregnancy by accident’ seemed to be softening circumstances over identification as “whore” (male adult participant from the general population). A girl from the general population called unmarried mothers “karashika” [witches].

In short, drivers triggering stigma against unmarried mothers were therefore primarily (a) perceived danger due to fear of the disliked behaviour being passed on to others, and status loss; (b) the perception of not adding value, and; (c) perceived responsibility and the underlying immorality for becoming an unmarried mother and the attached immorality. The drivers that catalysed stigma against CAAFAG were foremost (a) perceived danger due to fear for disliked behaviour to be passed on, and violence and the impact on one’s life and livelihood, next to (b) the perception of not contributing. Finally, the triggers of stigmatisation regarding the indigenous population are (a) perceived danger due to violence and its impacts and fear of the unknown, alongside (b) the perception regarding their inferiority and lower value. The perception of perceived danger in its various forms and perceived non-contribution were common across the three populations.

3.3 Theme 2: Stigma Facilitators

Five facilitators were prominent for at least two populations experiencing stigma, namely livelihood, personal benefit, family connection, leader connection, and behaviour change. Facilitators mentioned for only one population were comparison of the specific stigma against other stigmas, with some stigmas perceived worse than others, and the reference to humanity and shared interests.

A crucial factor for all three populations was livelihood, i.e. having an income. An adult male participant from the general population indicated money was essential for unmarried mothers: “they can be intelligent but if she doesn’t have resources, she will not develop”. Members of the general population mentioned poverty was a reason for CAAFAG to join armed groups, and income generating activities would help. CAAFAG themselves also emphasised livelihood was key, earning community respect, consideration and trust. A male participant from the indigenous population indicated that “if you don’t have financial resources, you will be seen as not useful”, and participants indicated power is with people with money. An unmarried mother said: “the worth of a woman in the community is defined by having resources”. Another recognised that having money was not the sole solution to their acceptance: “your presence and your absence (…) remain the same”. Next to financial resources, for unmarried mothers having a husband was also necessary to stabilise their household.

Personal benefit, whether the relationship could be personally fruitful, also appeared to be a facilitator. A male adult participant indicated the certainty about unmarried mothers that “she is not infertile but can have children”, and girls from the general population said that they could bring in money but also be a burden. CAAFAG could help, if close to the family, to take care of the children, and other participants indicated the benefit of their military lifestyle: “they could teach me how to find money, because of the experiences they have had in the armed groups”. CAAFAG themselves mentioned that they were also used for work requiring strength, or security. An unmarried mother, participant in the general population discussing CAAFAG, mentioned they could be marriage candidates, highlighting her own vulnerable position: “there is no civil boy that will marry you [me]”. Representatives from the indigenous population perceived being used for personal or community benefit, dancing for the King’s visit, or accessing donor finances. “The leaders justify their needs to humanitarian and other donors by using us as an object of visibility, and sometimes they feed us with hope. However, we are not involved in decision-making at the community level, and they don’t find solutions to our problems”. The benefit of the indigenous population to do manual labour, or to steal for them, was acknowledged by the general population. A boy said: “I find that the “pygmies” can be very useful sometimes, such as when we have community work to do”.

The RBGE paid specific attention to family connection as a potential facilitator. This differed between the three populations experiencing stigma. Most of the participants from the general population mentioned family connections would help towards acceptance of unmarried mothers: “She will stay in [be] my family until the end of times”. This was, however, accompanied by a statement underlining prejudice: “In every family, there are bad persons and good persons”. The responses in the general population concerning CAAFAG were mixed and hesitant: “I cannot reject them, but I will have to walk with him slowly, slowly”. Towards the indigenous population, adolescents from the general population in particular were adamant that close family connections did not equal acceptance: “to be close to my family doesn’t change the character or thoughts of the “pygmee””. Being family-related was seen as hypocritical and opportunitistic.

Closeness to leaders as a facilitator was explored as well and responses were mixed. Male adult participants from the general population shared their concern that, if married to a (previously) unmarried mother, closeness would mean she would also be “the leader’s wife”. Her close connection to leaders could give them trouble, as leaders would support their wife in the event of dispute. Others thought they could benefit from the relationship with leaders, indicating “my wealth will be secured”. Participants from the general population perceived a close relationship between leaders and CAAFAG positively, by copying proper behaviour and through the quick reporting of difficulties. Others were concerned that a leader could misuse CAAFAG and their military experience for personal gain. The same was said about the indigenous population, where close connections could positively change the behaviour of the indigenous population, while others feared the indigenous population would contaminate and corrupt leaders.

Another facilitator highlighted for unmarried mothers and CAAFAG was behaviour change. Being perceived to listen to advice was crucial for unmarried mothers, “to regain morality” and “leave behind their bad behaviour”. Also adult unmarried mothers emphasised listening to advice as a route to acceptance. CAAFAG were advised to give up perceived actions such as drinking, smoking and stealing, and to show kindness, listen to advice and go to church. With regard to associations both CAAFAG and the indigenous population indicated negative experiences, with membership unattainable due to costs, and potential discrimination if member; unmarried mothers had similar hesitations. Some CAAFAG however shared positive sides to associations, being a youngster like others when exercising, and the connection with others in society, facilitating integration. Education was mentioned, albeit limitedly, for all three populations. A participant from the general population indicated that unmarried educated mothers did not respect their education, demonstrated by their “disorderly life”.

There were some population-specific facilitators. Comparison, indicating there were worse behaviours, was applied to unmarried mothers. A male adult participant indicated the mother had taken responsibility by not aborting, indicating that abortion was seen as worse. Another male participant indicated other girls did not become unmarried mothers, but were “real whores”. For the indigenous population, oftentimes humanity was mentioned: “they are humans like us” and should therefore be greeted, business associates or marriage partners. Shared interests was another factor, for example through marketable products such as honey, or through shared religion.

In short, the main facilitators, identified for the three populations, seemed to be a stronger livelihood and personal benefit to de-intensify stigmatisation. While connection to the family seemed to be positive for most unmarried mothers to be accepted, this was mixed for CAAFAG. The connection to leaders was mixed for all three populations, depending on the trust regarding the leader’s intent. Belief in behaviour change and listening to advice was a facilitator concerning unmarried mothers and CAAFAG, while realising there is a shared humanity and potential shared interests, such as religion, was a facilitator specifically mentioned regarding the indigenous population. Finally, reflecting that there might be locally perceived worse behaviour that could have been chosen, such as abortion, was a softening factor for unmarried mothers.

3.4 Theme 3: Stigma Manifestations

The findings indicated that the populations experienced stigmatisation in different shapes and forms at the socio-ecological levels of family, community and services. All three populations were stereotyped by the general populations.

Stigma manifested itself at the family level, where unmarried mothers perceived participation as mostly negative, with some having positive examples. Decisions in their families, concerning inheritance or selling of a piece of land, were made without their participation or consent. They indicated family members saw them as “wasted effort”. An unmarried mother shared: “If I arrive and they are in a meeting, they ask me to return saying that I have nothing to say”. In contrast, some participants said their parents did support them with education, or asked their opinion. CAAFAG shared positive and negative examples, some discussing the challenge of family reintegration, with families not trusting them, not having the means to support them, or fearing they would harm them. Some shared that they felt supported by certain family members. Within the indigenous population, findings appeared to be divided by gender: men highlighted their positive status in family decision-making, while women emphasised they were not invited by both their original families nor by the family-in-law.

Stigma manifested itself at community level and with leaders in a mixed fashion; unmarried mothers and CAAFAG had positive and negative experiences, while the indigenous population primarily had negative experiences. Unmarried mothers shared that some leaders were approachable and helpful, while others highlighted that leaders abused their vulnerable position. Some mentioned that though some leaders were helpful, you had to bring money or “your file will be downgraded”. Some of CAAFAG emphasised how leaders supported their reintegration: “since my arrival in the community and me leaving the armed groups, it was the local leaders who I have considered as parents (…)”. More CAAFAG however were less positive, indicating that leaders were not supportive, side-lining and discriminating against them. Specific examples were when leaders did not address physical abuse of a particular youth, and their legal movement restrictions more generally, as a boy explained: “We are not authorised to travel between villages without approval from the local leader, because the community doesn’t trust us”. Men and women of the indigenous population encountered participation restrictions in community meetings: “If a Bantou arrives after you, and all seats are occupied, they will ask the indigenous population to give up their seat, and stand or sit on the floor”. A female participant from the indigenous population emphasised: “the community does nothing but catalyse the worsening of the problems of female pygmies”. An adult woman from the general population indicated that the indigenous population “will not approach the leaders as they have an inferiority complex”. Unmarried mothers indicated that they were not looking for friendships or association memberships outside of other unmarried mothers.

All three populations experiencing stigma experienced restrictions accessing services such as health, legal support and paid jobs, amongst others. They felt devaluated and neglected, “not being considered as persons”, and differentially treated. An unmarried mother, discussing the position of CAAFAG, indicated they were not employed as other workers, also not by NGOs, and that leaders in charge recruited family. This while, she emphasised,“we also have two hands to work with”. Also members of the indigenous population highlighted recruitment by NGOs: “the humanitarians themselves cannot recruit us to do quality work, because we cannot do anything”. Unmarried mothers traveled to another village for support, as they did not expect it locally. CAAFAG perceived differential treatment in health centers, such as higher bills if they were treated at all, and stayed home. This resonated with a boy from the indigenous population who called hospital visits a “waste of time”, opting to stay home where “we will await death”.

Unmarried mothers and CAAFAG emphasised the act of scapegoating, with CAAFAG feeling held responsible for adverse events. A boy indicated that scapegoating hampered interaction with other children: “"in a game, one can get hurt, and to escape that, we spare ourselves [to play with] children of the leaders, because if there is an accident, it is always the demobilised youth.” An unmarried mother said: “[it looks like] I’m one of those who killed Jesus”. Examples of anticipated stigma, where expectance of stigma and discrimation inhibits a person (Pescosolido and Martin 2015), were shared as participants indicated that they stayed at home, did not visit community events and did not try to participate in family discussions.

Labelling by the general population as a practice of stigmatisation featured meagerly in this study, except for two participants indicating that someone from the indigenous population got angry when labelled as ‘pygmee’.

Within the manifestations, we specifically highlight stereotyping as a prominent feature within the data for all populations experiencing stigma. Unmarried mothers were mostly stereotyped on perceived sex-drive and lack of intelligence, and women from the general population described how they demonstrated their dissatisfaction with unmarried mothers: “the mothers that live in their households spit on the floor to signify that they are not seen as a person”. CAAFAG were stereotyped as thieves, bandits, delinquents and by one male adult group specifically as drunk and pot-smoking. As a male participant said: “Maybe, because the demobilised youth here are not trained by an NGO or local leader, I cannot do business with them, as I have fears he will steal my capital or merchandise”. An additional and related stereotype was perceived violence and danger, that they “could easily take a machete and kill you”. Stereotypes allocated to the indigenous population were perceived strong odour, lack of intelligence, danger and capricious. A boy from the general population: “they are superthieves.” Participants indicated strong odour impeded cooperation, and a boy from the general population emphasised: "to live with the “pygmee” children, one needs a strong heart because of their bad smell”.

In short, while male representatives of the indigenous population had largely positive feelings regarding their status in the family, CAAFAG had mixed experiences and unmarried mothers and female representation of the population mostly negative. CAAFAG presented mixed opinions about their perceived support in the community, with some positive examples regarding the community leaders, while unmarried mothers had mixed feelings regarding community and leaders, and the indigenous population felt they were not accepted. With regard to services, all three populations felt devaluated and differentially treated. Stereotypes were common for all three populations, with mothers perceived to have a high sex-drive and be unintelligent, CAAFAG seen as thieves, bandits, pot-smoking and dangerous, and the indigenous population as thieves with a strong odour.

Table 2 summarises the findings regarding the three main categories.

3.5 Theme 4: Stigma Outcomes

Quality of life outcomes, as part of the HSDF, were not solicited during data collection, but were captured in some instances. CAAFAG provided no information, except for one participant highlighting the challenge to send their children to school. Some unmarried mothers felt fear when approached, and did not feel respected or experience joy in their household. “They [little brothers and sisters] see you as someone chased out of the house, you have no joy, you will stay with that label”. Some participants from the general population recognised harms of stigmatisation and exclusion, saying they brought stress upon the unmarried mothers, removed peace from their heart and potentially led to suicide. An unmarried mother further identified that, because of having children while unmarried, they did not benefit from programmes meant for youth as they were automatically no longer seen as youth. Some members of the indigenous population shed light that these experiences were potentially traumatising events, sharing built-up internal frustration. A participant added: “don’t be surprised when one day we arrive to revolt”.

3.6 Positive Community Examples

The data featured a number of positive examples between the populations experiencing stigma and the general population, which merit specific mentioning. They link to some facilitators as well as are examples that drivers and manifestations can be defied.

Unmarried mothers discussed a local association ‘Unity brings Power’, with married and unmarried mothers as members, where they could earn some money. Furthermore, peers were emphasised as a support group, as were some family members. Also members from the general population shared positive examples, knowing a boy who married a (formerly unmarried) mother. Other male participants shared concerns about the vulnerable position of unmarried mothers. A female participant from the general population added that through church they shared religion, while a male participant indicated that confidence in himself allowed him to acquaint with unmarried mothers.

CAAFAG mentioned that they felt accepted by some organisations and institutes, such as a specific church and some health centres and associations. Some participants mentioned local leaders’ support in integration. One male participant indicated he would welcome back his son into his family, and a boy said that as family he could advise him to not recruit. Other participants said they had friends amongst CAAFAG. Opinions differed whether CAAFAG brought more peace and security, or were the cause of insecurity.

One of the support factors mentioned by the indigenous population was turning to God, citing the Bible: “I will lift up my eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh help; help is in the lord, the heaven and the earth belong to him”. Some indicated support from friends or parents, others that both Bantous and the indigenous population could be asked for support. One example by the general population concerned shared religious interest: “No, because discrimination is not the objective of the church; they all come to church to pray to God. And there are actually persons that share the microphone or megaphone with “pygmies”.” Other participants said they were ready to peacefully co-exist with the indigenous population, said that there were ‘clean “pygmies”’, and interest in their fishing and hunting culture: “Because the “pygmies” love hunting, children wish to know how to hunt. And when they go fishing for eels in the river, some children follow the “pygmies”.”

4 Discussion

This study was conducted regarding the stigmatisation of three populations experiencing stigma, using a RBGE for all groups from the general population, and another RBGE for all groups from the populations experiencing stigma. Stigmatisation of the three populations showed resemblance when comparing the stigma drivers, facilitators and manifestations of the three populations, while having population-specific elements.

4.1 Drivers

Perceived danger featured as the main driver in all populations. This resonates with conclusions drawn on ‘former child soldiers’ in Uganda, where stigma was driven by fear of contamination of ‘abnormal behaviour’ (Ertl et al. 2014) and on girls formerly associated with armed forces in eastern DRC, where they were thought to badly influence their peers (Tonheim 2012). Although the general population did not indicate they held the CAAFAG responsible for experienced violence, as in Uganda (Schneider et al. 2018), fear of current violence was perceived. Stereotyping substance abuse of CAAFAG was identified, comparable to addictions described as a challenge for former child soldiers in DRC (Johannessen and Holgersen 2014) and consistent to references of ill mental health in Uganda (Schneider et al. 2018). CAAFAG referred to the community fear that they remained indoctrinated with ‘military style’, echoing similar sentiments from peers in Colombia (Denov and Marchand 2014) and another study in DRC (Johannessen and Holgersen 2014). Fear of HIV transmission, mentioned regarding CAAFAG in Uganda (Schneider et al. 2018), was allocated in this study only to unmarried mothers. Non-contribution or limited value as driver aligns in the case of the indigenous population with conclusions from Central Africa where”pygmies” were seen as backward and inferior (Markowska-Manista 2017; Vries 2018) and being exploited, as a study in DRC regarding the Mbuti “Pygmies” concluded (Kamuha 2013). The perception of own responsibility for the stigmatised status was only discussed with regard to unmarried mothers in this study, while in Uganda, how youth became associated with armed groups did not really affect their feeling of stigmatisation (Ertl et al. 2014).

4.2 Facilitators

Factors that can intensify or mitigate stigmatisation were partially cross-populations, such as livelihood and personal benefit or gain. While personal benefit did not surface in other studies to our knowledge, the importance of opportunies for employment, to accompany adjustment and reintegration into the environment, was highlighted with regard to CAAFAG in Sierra Leone (Betancourt et al. 2014). Another facilitator identified in our data indicated that there were worse characteristics by comparison than being an unmarried mother, mentioning she was responsible enough not to abort, which echoes a study from the Maldives, calling extra-marital pregnancy and abortion a double-sin (Hameed 2018). Literature has indicated that abortion was indeed also stigmatised in DRC (Casey et al. 2019; Steven et al. 2019). Though not an outcome of this study, contraception use, to avoid falling pregnant out of marriage, also carried a stigma in DRC (Muanda et al. 2018). The demand for behaviour change of CAAFAG and unmarried mothers as a facilitator is supported in other studies. In Burundi it was indicated that CAAFAG were used as examples by parents of how their children should not behave (Song et al. 2014), and in Uganda out-of-wedlock sex or pregnancy was perceived outside of the community norm (Leerlooijer et al. 2013) and shameful (Rossier 2007), with both children born out-of-wedlock and mothers called ‘spoilt’ or ‘destroyed’ (Mturi and Moerane 2001). Therefore, data from this study seems to indicate that stigma of unmarried mothers, being stereotyped as having a high sex-drive, relates to norms enforcement, one of the functions of stigmatisation (Phelan et al. 2008; Bos et al. 2013) also found in other studies (Leerlooijer et al. 2013). People do not want them to behave as a “woman without a moral” or a “bad woman” (Amroussia et al. 2017) and are concerned that if they acquaint with them, they might behave and become like them. This fear of passing on bad behaviour echoes an earlier study conducted regarding girls associated with armed forces and groups (Tonheim 2014). The function of stigma of CAAFAG, again with emphasis on potential behaviour transfer, was in another study attached to ‘disease avoidance’ (Ertl et al. 2014). Stigmatisation of the indigenous population seems to point to the function of exploitation and domination, so perceived by the indigenous population themselves, and identified as useful by the general population when it comes to labour. This echoes the study regarding the Mbuti indigenous population in DRC (Kamuha 2013).

4.3 Manifestations

Manifestations were observed and felt at family, community and services level and experiences of stigma across the three populations manifested themselves in comparable fashion, though with population-specific examples. While most unmarried mothers in our study indicated that they did not feel supported or accepted by their families, another study regarding school-going teenage mothers in South Africa indicated that families eventually accepted the pregnancy, though no reference is made by the participants to emotional support (Amod et al. 2019). CAAFAG had mixed experiences in their engagement with their family, which has been identified as a protective factor regarding reintegration and psychosocial wellbeing (Betancourt et al. 2013). The manifestation of discrimination and exclusion at family level seemed to be different for male and female representatives from the indigenous population, where women felt they were not able to participate. This is in line with findings regarding the indigenous Nasa population of Colombia (Navarro-Mantas & Ozemela 2019). While manifestations at community level were experienced by all, it seemed to be most negative for the indigenous population, male and female alike. Restrictions to health services was felt by all, but specifically by CAAFAG and the indigenous population. This is consistent with experiences in other studies, where they felt discrimination in access to care (Cerón et al. 2016), fearing that they would be discriminated against or humiliated (Sandes et al. 2018) and differentially treated (Đào et al., 2019). Various studies regarding the indigenous population highlight their social exclusion regarding health services and its consequences (Willis et al. 2006; Anderson et al. 2016).

4.4 Stigma Outcomes

While this study did not collect specific data on outcomes of stigma, there were indications that stigma impacted upon their psychosocial wellbeing and opportunities. This was consistent with conclusions drawn in other studies regarding stigmatisation, such as psychological distress due to anti-Haitian sentiments in the Dominican Republic during an cholera outbreak (Keys et al. 2019), depression, anxiety, depresion, avoidance and distraction due to stigma regarding cancer and related body image disorder in Iran (Shiri et al. 2018) and negative emotions, feelings of embarrassment and sadness due to stigmatisation of sexworkers in Vietnam (Huber et al. 2019). Their peers in other settings felt the consequences of stigmatisation as well, such as anticipated stigma by fearing physical punishment or differential treatment at healthcare providers for being young, sexually active and unmarried in Tanzania (Nyblade et al. 2017), or potentially high levels of psychosocial distress for CAAFAG if not accepted back into the community upon return in Nepal (Kohrt et al. 2010).

This study showed that a population experiencing stigma never felt one hunderd percent stigmatised. Some CAAFAG indicated they felt supported by local leaders, while others mentioned they weren’t. Some unmarried mothers shared they were not respected by their family, while some indicated that they were. Some members of the indigenous population highlighted how they felt discriminated against and exploited, while some members of the general population emphasised humanity and sharing of interests such as religion. This finding was in line with other studies, for example regarding CAAFAG in Uganda (Schneider et al. 2018) and Burundi (Song et al. 2014), and single mothers in Tunisia (Amroussia et al. 2017).

4.5 Input for Stigma Reduction Strategies

Albeit carefully, as stigmatisation is a sensitive topic, the limited knowledge on what specifically works to address stigmatisation succesfully and durably, and the need to temper the findings due to the study limitations, we reflect on how this study can potentially inform stigma reduction strategies, by understanding the drivers, facilitators and manifestations. We do so from the perspective of a socio-ecological stigma reduction strategy framework (Heijnders and VanderMeij 2006; Hartog et al. 2019). Depending on the contextual information, strategies can be applied and adjusted for each population.

The data made clear that bearing the brunt of stigmatisation can trigger an inferiority complex or anticipated stigma, and that to reduce stigmatisation and its effects, strengthening of the population experiencing stigma could be investigated. Within existing stigma reduction interventions, at the personal level of populations experiencing stigma, empowerment strategies have been employed such as livelihood, peer support and strengtening self-confidence. Peer support groups are strategies currently used in stigma reduction interventions such as ones to tackle epilepsy (Elafros et al. 2013) and HIV (Mburu et al. 2013) stigma. Various stigma reduction interventions employ livelihood empowerment strategies to mitigate stigma, such as of HIV (Tsai et al. 2017) and leprosy (Ebenso and Ayuba 2010; Dadun et al. 2017). Furthermore, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) are used to diminish self-stigma, such as in HIV (Tshabalala and Visser 2011) or weight self-stigma (Griffiths et al. 2018).

At the interpersonal socio-ecological level we observed within this study that some families do—and other families do not—accept or support the unmarried mothers and CAAFAG. Including respected families that accept and support them as role-models for the other families, potentially through a buddy-system (Zuyderduin et al. 2008), is an approach that can be further investigated.

At the organisational level, our findings indicated that most populations experienced challenges with the services delivered within their community. They felt differentially treated and sometimes opted therefore to not pursue a service and accept the consequences. Educational and contact-based trainings for service providers, and a reflective look at the potentially discriminatory nature of their policies and practice, could be helpful to address stigma such as interventions tacklings stigma of HIV (Lohiniva et al. 2016), HIV and sexually marginalized populations (Geibel et al. 2017) or mental illness (Bayar et al. 2009). Community leaders and NGOs, as service providers in the community, should also be part of this effort as they were not always seen as supportive.

At the community level, CAAFAG saw their mobility impeded by the obligation to request approval to leave their area. Advocacy towards the local chiefs for removal of this local law may reduce their restrictions. In parallel, the potential role of leaders was reflected upon, and not automatically positive. Reducing stigma through the support of popular opinion leaders, both formal and informal, is an employed strategy in stigma reduction interventions (Somerville et al. 2006; Young et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013) However, their status within the community should be critically reviewed, as this study indicated that they were awarded with both negative and positive emotions.

Fear was a strong emotion viz-a-viz the three populations, and creating positive experiences and contact with the population experiencing stigma could be explored. Contact-based stigma strategies have been identified as one of the most promising strategies to reduce stigma, with study limitations or strategy additions acknowledged (Brown et al. 2003; Couture and Penn 2003), and a recent review indicated that conclusions regarding effectiveness of contact strategies is built on imprecise evidence (Jorm 2020). Another driver, perceived non-contribution to the community, could be tackled by exploring more collaborative contact-based projects from an equal basis, to emphasise the value of each and everyone involved to avoid strengthening (the feelings of) exploitation.

This study demonstrated that data generated from a generic exercise, combining reactions with more in-depth explanations, was compatible with an overarching framework to understand stigmatisation of a specific population. It seemed to imply that such an exercise can be used with regard to different populations experiencing stigma. Both adolescents and adults were participants within this study. Adolescents from the general population seemed less inclined to provide socially desirable answers and stated their perceived facts in a more outspoken manner, in which the indigenous population smelled strongly and were thieves, unmarried mothers prostitutes and immoral, and CAAFAG dangerous and bandits. We argue that collecting data from children and adolescents, and adults alike, will balance the contextual information of stigmatisation regarding a specific population, could provide information concerning specific challenges experienced by children and adolescents within a population experiencing stigma, and can shed light which stigma reduction strategies need to be used for which target group.

4.6 Strengths and Limitations

The present study was innovative as it indicated that contextual knowledge regarding stigmatisation can be collected through the used exercise and tool. This implies that this exercise can be considered to be part of a stigma reduction intervention to contextually inform the intervention and underlying strategies itself. The study further combined and compared perceptions from the general population and populations experiencing stigma, women and men and adults and adolescents alike. While adolescents were participants, they were underrepresented, as in many other studies regarding stigma (Hartog et al. 2019; Kane et al. 2019). As the study was facilitated by an NGO, participants were identified through familiar channels and community groups, potentially creating selection bias. The selection of participants known to the organisation, and their awareness of the organisation’s work, might have influenced the answers given and the data gathered, and therefore the conclusions drawn. As the RBGE is a group exercise, there is potential for socially desirable answers. This was partially addressed by asking what other people in the community would respond to the question, instead of the participants themselves. This technique is also used in other studies such as Babalola and colleagues (2015). Research teams indicated that while most participants were actively engaged, some participants were less expressive, which may have led participants that are more active to be dominant in steering the conversation. This has been partially tackled by integrating first a reaction into the exercise, by individually indicating yes, maybe or no as the initial answer. Another limitation was that audio-data was translated while transcribing, which could mean loss of information and interpretation by transcribers. The data was coded and analysed by one researcher [KH], which can have skewed the findings to specific conclusions. Comparison with like-minded studies, however, has shown similarities in findings. The findings have indicated that there are differences within how much population members potentially experience stigma. While the facilitators might be partially explanatory factors for that, this study did not further explore the elements of resilience. A final limitation is that this study was conducted in one village, which impacts the generalisability of the study findings. However, when comparing with other studies in different settings regarding the similar population, there seems to be ample overlap in some of the stigmatisation elements.

5 Conclusion

This study provided insights into the stigmatisation of three different, non health-stigma related populations experiencing stigma in DRC, based on a health-related stigma and discrimination framework, and found that there were comparable drivers such as perceived danger, facilitators as livelihood and manifestations as participation restrictions, though that in-depth understanding came from soliciting further details. General population and populations experiencing stigma provided complementary information. Adolescents were more outspoken than adults. In all three populations there were also positive examples of acceptance and support. Reflections regarding potential stigma reduction strategies were given. Investing in contextual understanding of stigmatisation of a specific population seems possible and is recommended within stigma reduction interventions to tailor the response towards identified drivers, facilitators and manifestations. Further research into positive examples of acceptance is recommended.

References

Amod, Z., Halana, V., & Smith, N. (2019). School-going teenage mothers in an under-resourced community: lived experiences and perceptions of support. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(9), 1255–1271.

Amroussia, N., Hernandez, A., Vives-Cases, C., & Goicolea, I. (2017). “Is the doctor God to punish me?!” An intersectional examination of disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth against single mothers in Tunisia. Reproductive health, 14(1), 32.

Anderson, I., Robson, B., Connolly, M., Al-Yaman, F., Bjertness, E., King, A., et al. (2016). Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. The Lancet, 388(10040), 131–157.

Babalola, S., John, N. A., Cernigliaro, D., & Dodo, M. (2015). Perceptions about survivors of sexual violence in Eastern DRC: Conflicting descriptive and community-prescribed norms. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(2), 171–188.

Bachmann, S. D., & Frost, T. (2015). Justice in transition: On territory, restitution and history. Current issues in transitional justice (pp. 83–108). Berlin: Springer.

Bayar, M. R., Poyraz, B. C., Aksoy-Poyraz, C., & Arikan, M. K. (2009). Reducing mental illness stigma in mental health professionals using a web-based approach. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 46(3), 226.

Bennett, L. R. (2001). Single women's experiences of premarital pregnancy and induced abortion in Lombok, Eastern Indonesia. Reproductive Health Matters, 9(17), 37–43.

Betancourt, T. S., Agnew-Blais, J., Gilman, S. E., Williams, D. R., & Ellis, B. H. (2010). Past horrors, present struggles: The role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038.

Betancourt, T. S., Borisova, I., Williams, T. P., Meyers-Ohki, S. E., Rubin-Smith, J. E., Annan, J., et al. (2013). Research Review: Psychosocial adjustment and mental health in former child soldiers—a systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(1), 17–36.

Betancourt, T. S., McBain, R., Newnham, E. A., & Brennan, R. T. (2014). Context matters: Community characteristics and mental health among war-affected youth in Sierra Leone. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(3), 217–226.

Bos, A. E., Schaalma, H. P., & Pryor, J. B. (2008). Reducing AIDS-related stigma in developing countries: The importance of theory-and evidence-based interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13(4), 450–460.

Bos, A. E., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim., (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746147.

Brakel, V., Cataldo, J., Grover, S., Kohrt, B. A., Nyblade, L., Stockton, M., et al. (2019). Out of the silos: Identifying cross-cutting features of health-related stigma to advance measurement and intervention. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1245-x.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513.

Brown, L., Macintyre, K., & Trujillo, L. (2003). Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844.

Carson, S. L., Kentatchime, F., Sinai, C., Van Dyne, E. A., Nana, E. D., Cole, B. L., et al. (2019). Health challenges and assets of forest-dependent populations in cameroon. EcoHealth, 16(2), 287–297.

Casey, S. E., Steven, V. J., Deitch, J., Dumas, E. F., Gallagher, M. C., Martinez, S., et al. (2019). “You must first save her life”: community perceptions towards induced abortion and post-abortion care in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1571309.

Cerón, A., Ruano, A. L., Sánchez, S., Chew, A. S., Díaz, D., Hernández, A., et al. (2016). Abuse and discrimination towards indigenous people in public health care facilities: experiences from rural Guatemala. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 77.

Chambers, L. A., Rueda, S., Baker, D. N., Wilson, M. G., Deutsch, R., Raeifar, E., et al. (2015). Stigma, HIV and health: A qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 848. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0.

Christian, M., Safari, O., Ramazani, P., Burnham, G., & Glass, N. (2011). Sexual and gender based violence against men in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Effects on survivors, their families and the community. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 27(4), 227–246.

Couture, S., & Penn, D. (2003). Interpersonal contact and the stigma of mental illness: A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 12(3), 291–305.

Cross, H. A., Heijnders, M., Dalal, A., Sermrittirong, S., & Mak, S. (2011). Interventions for stigma reduction–Part 1: Theoretical considerations. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development, 22(3), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v22i3.70.

Dadun, D., Brakel, W. H., Peters, R. M. H., Lusli, M., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., & Bunders, J. G. F. (2017). Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Leprosy Review, 88(1), 2–22.

Đào, L. U., Terán, E., Bejarano, S., Hernandez, I., Ortiz, M. R., Chee, V., et al. (2019). Risk and resiliency: The syndemic nature of HIV/AIDS in the indigenous highland communities of Ecuador. Public Health, 176, 36–42.

Denov, M., & Marchand, I. (2014). “One cannot take away the stain”: Rejection and stigma among former child soldiers in Colombia. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 20(3), 227.

Ebenso, B., & Ayuba, M. (2010). 'Money is the vehicle of interaction': Insight into social integration of people affected by leprosy in northern Nigeria. Leprosy Review, 81(2), 99.

Elafros, M. A., Mulenga, J., Mbewe, E., Haworth, A., Chomba, E., Atadzhanov, M., et al. (2013). Peer support groups as an intervention to decrease epilepsy-associated stigma. Epilepsy & Behavior, 27(1), 188–192.

Ertl, V., Pfeiffer, A., Schauer-Kaiser, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2014). The challenge of living on: Psychopathology and its mediating influence on the readjustment of former child soldiers. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e102786.

Gebremedhin, S. A., & Tesfamariam, E. H. (2017). Predictors of HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitude among young women of Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo: cross-sectional study. J AIDS Clin Res, 8(3), 677.

Geibel, S., Hossain, S. M., Pulerwitz, J., Sultana, N., Hossain, T., Roy, S., et al. (2017). Stigma reduction training improves healthcare provider attitudes toward, and experiences of, young marginalized people in Bangladesh. (Special Issue: Integrating rights into HIV and sexual and reproductive health: Evidence and experiences from the link up project.). Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), S35–S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.026.

Glass, N., Kohli, A., Surkan, P. J., Remy, M. M., & Perrin, N. (2018). The relationship between parent mental health and intimate partner violence on adolescent behavior, stigma and school attendance in families in rural Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Mental Health, 5.

Greiner, A. L., Albutt, K., Rouhani, S. A., Scott, J., Dombrowski, K., VanRooyen, M. J., et al. (2014). Respondent-driven sampling to assess outcomes of sexual violence: A methodological assessment. American Journal of Epidemiology, 180(5), 536–544.

Griffiths, C., Williamson, H., Zucchelli, F., Paraskeva, N., & Moss, T. (2018). A systematic review of the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for body image dissatisfaction and weight self-stigma in adults. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(4), 189–204.

Hameed, S. (2018). To be young, unmarried, rural, and female: intersections of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the Maldives. Reproductive Health Matters, 26(54), 61–71.

Hartog, K., Hubbard, C. D., Krouwer, A. F., Thornicroft, G., Kohrt, B. A., & Jordans, M. J. (2019). Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: Systematic review of intervention strategies. Social Science & Medicine, 246, 112749.

Heijnders, M., & Van der Meij, S. (2006). The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600595327.

Houghton, F. (2004). Flying solo: single/unmarried mothers and stigma in Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 21(1), 36–37.

Huber, J., Ferris France, N., Nguyen, V. A., Nguyen, H. H., Thi Hai Oanh, K., & Byrne, E. (2019). Exploring beliefs and experiences underlying self-stigma among sex workers in Hanoi. Vietnam. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21, 1425–1438.

Johannessen, S., & Holgersen, H. (2014). Former child soldiers’ problems and needs: Congolese experiences. Qualitative Health Research, 24(1), 55–66.

Jones, E. E. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York: WH Freeman.

Jorm, A. F. (2020). Effect of contact-based interventions on stigma and discrimination: A critical examination of the evidence. Psychiatric Services, appi. ps. 201900587.

Kamuha, M. W. (2013). Encountering the Mbuti Pygmies: a challenge to Christian mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Kane, J. C., Elafros, M. A., Murray, S. M., Mitchell, E. M., Augustinavicius, J. L., Causevic, S., et al. (2019). A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 17.

Kemp, C. G., Jarrett, B. A., Kwon, C. S., Song, L., Jetté, N., Sapag, J. C., et al. (2019). Implementation science and stigma reduction interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1237-x.

Keys, H. M., Kaiser, B. N., Foster, J. W., Freeman, M. C., Stephenson, R., Lund, A. J., et al. (2019). Cholera control and anti-Haitian stigma in the Dominican Republic: from migration policy to lived experience. Anthropology & Medicine, 26(2), 123–141.

Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., et al. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525.

Kohli, A., Perrin, N., Mpanano, R. M., Banywesize, L., Mirindi, A. B., Banywesize, J. H., et al. (2015). Family and community driven response to intimate partner violence in post-conflict settings. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 276–284.

Kohrt, B. A., Tol, W. A., Pettigrew, J., & Karki, R. (2010). Children and revolution: mental health and psychosocial well-being of child soldiers in Nepal.

Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J., Koirala, S., & Worthman, C. M. (2015). Designing mental health interventions informed by child development and human biology theory: A social ecology intervention for child soldiers in Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(1), 27–40.

Leerlooijer, J. N., Bos, A. E., Ruiter, R. A., Reeuwijk, M. A., Rijsdijk, L. E., Nshakira, N., et al. (2013). Qualitative evaluation of the Teenage Mothers Project in Uganda: A community-based empowerment intervention for unmarried teenage mothers. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 816.

Li, L., Guan, J., Liang, L. J., Lin, C., & Wu, Z. (2013). Popular opinion leader intervention for HIV stigma reduction in health care settings. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(4), 327–335.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363.

Lohiniva, A.-L., Benkirane, M., Numair, T., Mahdy, A., Saleh, H., Zahran, A., et al. (2016). HIV stigma intervention in a low-HIV prevalence setting: A pilot study in an Egyptian healthcare facility. AIDS Care, 28(5), 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1124974.

Markowska-Manista U (2017). The written and unwritten rights of indigenous children in Central Africa–between the freedom of “tradition” and enslavement for “development”. Symbolic Violence in Socio-Educational Contexts, 127.

Mburu, G., Ram, M., Skovdal, M., Bitira, D., Hodgson, I., Mwai, G. W., et al. (2013). Resisting and challenging stigma in Uganda: the role of support groups of people living with HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18636.

Mturi, A. J., & Moerane, W. (2001). Premarital childbearing among adolescents in Lesotho. Journal of Southern African Studies, 27(2), 259–275.

Muanda, F. M., Gahungu, N. P., Wood, F., & Bertrand, J. T. (2018). Attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health among adolescents and young people in urban and rural DR Congo. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 74.

Mukolo, A., Heflinger, C. A., & Wallston, K. A. (2010). The stigma of childhood mental disorders: A conceptual framework. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.10.011.

Murray, S. M., Augustinavicius, J., Kaysen, D., Rao, D., Murray, L. K., Wachter, K., et al. (2018). The impact of cognitive processing therapy on stigma among survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Conflict and Health, 12, e1.

Murray, S. M., Robinette, K. L., Bolton, P., Cetinoglu, T., Murray, L. K., Annan, J., et al. (2018). Stigma among survivors of sexual violence in Congo: Scale development and psychometrics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(3), 491–514.

Musumari, P. M., & Feldman, M. D. (2013). "If I have nothing to eat, I get angry and push the pills bottle away from me": A qualitative study of patient determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care, 25(10), 1271–1277.

Mwandumba, J. V. (2015). Children on the battlefield: A look into the use of child soldiers in the DRC conflict.

Navarro-Mantas, L., & Ozemela, L. M.-G (2019). Violence against the Indigenous women: Methodological and ethical recommendations for research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260519825879.

Nayar, U. S., Stangl, A. L., Zalduondo, B., & Brady, L. M. (2014). Reducing stigma and discrimination to improve child health and survival in low-and middle-income countries: Promising approaches and implications for future research. Journal of Health Communication, 19(sup1), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.930213.

Newman, J. E., Edmonds, A., Kitetele, F., Lusiama, J., & Behets, F. (2012). Social support, perceived stigma, and quality of life among HIV-positive caregivers and adult relatives of pediatric HIV index cases in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 7(3), 237–248.

Nkamba, D., Mwenechanya, M., Kilonga, A. M., Cafferata, M. L., Berrueta, A. M., Mazzoni, A., et al. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of antenatal syphilis screening and treatment for the prevention of congenital syphilis in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia: Results of qualitative formative research. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 556.

Nyblade, L., Stockton, M., Nyato, D., & Wamoyi, J. (2017). Perceived, anticipated and experienced stigma: exploring manifestations and implications for young people’s sexual and reproductive health and access to care in North-Western Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19(10), 1092–1107.

Pescosolido, B., & Martin, J. K. (2015). The stigma complex. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145702.

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Dovidio, J. F. (2008). Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 358.

Rao, D., Elshafei, A., Nguyen, M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Frey, S., & Go, V. F. (2019). A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: State of the science and future directions. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1244-y.

Reading, J., Loppie, C., & O'Neil, J. (2016). Indigenous health systems governance from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) to Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). International Journal of Health Governance, 21(4), 222–228.

Rossier, C. (2007). Abortion: An open secret? Abortion and social network involvement in Burkina Faso. Reproductive Health Matters, 15(30), 230–238.

Rouhani, S. A., Scott, J., Greiner, A., Albutt, K., Hacker, M. R., Kuwert, P., et al. (2015). Stigma and parenting children conceived from sexual violence. Pediatrics, 136(5), e1195–e1203.

Sandes, L. F., Freitas, D. A., & Leite, K. B. (2018). Primary health care for South-American indigenous peoples: An integrative review of the literature. Pan American Journal of Public Health, 42, e163–e163.

Schneider, A., Conrad, D., Pfeiffer, A., Elbert, T., Kolassa, I. T., & Wilker, S. (2018). Stigmatization is associated with increased PTSD risk and symptom severity after traumatic stress and diminished likelihood of spontaneous remission—A study with east-african conflict survivors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 423.

Scott, J., Rouhani, S., Greiner, A., Albutt, K., Kuwert, P., Hacker, M. R., et al. (2015). Respondent-driven sampling to assess mental health outcomes, stigma and acceptance among women raising children born from sexual violence-related pregnancies in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. BMJ Open, 5(4), e007057.

Shiri, F. H., Mohtashami, J., Manoochehr, H., Rohani, C. (2018). Explaining the meaning of cancer stigma from the point of view of Iranian stakeholders: A qualitative study. International Journal of Cancer Management, 11(7).

Somerville, G. G., Diaz, S., Davis, S., Coleman, K. D., & Taveras, S. (2006). Adapting the popular opinion leader intervention for Latino young migrant men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention, 18, 137–148.

Song, S. J., Tol, W., & Jong, J. (2014). Indero: Intergenerational trauma and resilience between burundian former child soldiers and their children. Family Process, 53(2), 239–251.

Stangl, A. L., Earnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., van Brakel, W., Simbayi, L. C., Barré, I., et al. (2019). The health stigma and discrimination framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 31.

Steven, V. J., Deitch, J., Dumas, E. F., Gallagher, M. C., Nzau, J., Paluku, A., et al. (2019). “Provide care for everyone please”: Engaging community leaders as sexual and reproductive health advocates in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 98.

Thiessen, S. (2016). First Nations cultural approaches to work in Canada: A multiple case study. Northcentral University.

Tonheim, M. (2012). ‘Who will comfort me?’ Stigmatization of girls formerly associated with armed forces and groups in eastern Congo. The International Journal of Human Rights, 16(2), 278–297.

Tonheim, M. (2014). Genuine social inclusion or superficial co-existence? Former girl soldiers in eastern Congo returning home. The International Journal of Human Rights, 18(6), 634–645.

Tsai, A. C., Hatcher, A. M., Bukusi, E. A., Weke, E., Hufstedler, L. L., Dworkin, S. L., et al. (2017). A livelihood intervention to reduce the stigma of HIV in rural Kenya: Longitudinal qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 248–260.

Tshabalala, J., & Visser, M. (2011). Developing a cognitive behavioural therapy model to assist women to deal with HIV and stigma. South African Journal of Psychology, 41(1), 17–28.

Tshingani, K., Ntetani, M. A., Nsakala, G. V., Ekila, M. B., Donnen, P., & Dramaix-Wilmet, M. (2017). Influential factors and barriers to opt for the uptake of HIV testing among the adult population at HIV-care admission in an area in the DR Congo: What can we learn? HIV & AIDS Review. International Journal of HIV-Related Problems, 16(4), 220–225.

Venables, E., Casteels, I., Sumbi, E., & Goemaere, E. (2019). “Even if she’s really sick at home, she will pretend that everything is fine.”: Delays in seeking care and treatment for advanced HIV disease in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0211619.

Verelst, A., Schryver, M., Broekaert, E., & Derluyn, I. (2014). Mental health of victims of sexual violence in eastern Congo: Associations with daily stressors, stigma, and labeling. BMC Women's Health, 14(1), 106.

Vries, D. (2018). Navigating violence and exclusion: The Mbororo’s claim to the Central African Republic’s margins. Geoforum, 109, 162–170.

Wachter, K., Murray, S. M., Hall, B. J., Annan, J., Bolton, P., & Bass, J. (2018). Stigma modifies the association between social support and mental health among sexual violence survivors in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Implications for practice. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(4), 459–474.

Wark, C., & Galliher, J. F. (2007). Emory Bogardus and the origins of the social distance scale. The American Sociologist, 38(4), 383–395.

Willis, R., Jackson, D., Nettleton, C., Good, K., & Mugarura, B. (2006). Health of Indigenous people in Africa. The Lancet, 367(9526), 1937–1946.

Young, S. D., Konda, K., Caceres, C., Galea, J., Sung-Jae, L., Salazar, X., et al. (2011). Effect of a community popular opinion leader HIV/STI intervention on stigma in urban, coastal Peru. AIDS and Behavior, 15(5), 930–937.

Young-Lin, N., Namugunga, E. N., Lussy, J. P., & Benfield, N. (2015). Healthcare providers’ perspectives on the social reintegration of patients after surgical fistula repair in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 130(2), 161–164.