Abstract

Purpose

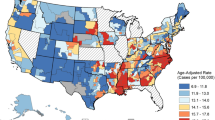

To describe and elucidate rates in breast cancer incidence by subtype in the federally designated Mississippi Delta Region, an impoverished region across eight Southern/Midwest states with a high proportion of Black residents and notable breast cancer mortality disparities.

Methods

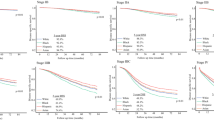

Cancer registry data from seven LMDR states (Missouri was not included because of permission issues) were used to explore breast cancer incidence differences by subtype between the LMDR’s Delta and non-Delta Regions and between White and Black women within the Delta Region (2012–2014). Overall and subtype-specific age-adjusted incidence rates and rate ratios were calculated. Multilevel negative binomial regression models were used to evaluate how individual-level and area-level factors, like race/ethnicity and poverty level, respectively, affect rates of breast cancers by subtype.

Results

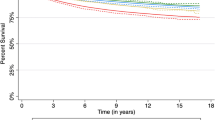

Women in the Delta Region had higher rates of triple-negative breast cancer, the most aggressive subtype, than women in the non-Delta (17.0 vs. 14.4 per 100,000), but the elevated rate was attenuated to non-statistical significance in multivariable analysis. Urban Delta women also had higher rates of triple-negative breast cancer than non-Delta urban women, which remained in multivariable analysis. In the Delta Region, Black women had higher overall breast cancer rates than their White counterparts, which remained in multivariable analysis.

Conclusion

Higher rates of triple-negative breast cancer in the Delta Region may help explain the Region’s mortality disparity. Further, an important area of future research is to determine what unaccounted for individual-level or social area-level factors contribute to the elevated breast cancer incidence rate among Black women in the Delta Region.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Delta Regional Authority (2017) Today’s Delta: a research tool for the region: 3rd edition. http://dra.gov/images/uploads/content_files/DRA_Todays_Delta_2016.pdf Accessed 9 Aug 2017

Delta Regional Authority (2016) Promoting a healthy Delta. http://dra.gov/initiatives/promoting-a-healthy-delta/. Accessed 5 Nov 2016

Gennuso KP, Jovaag A, Catlin BB, Rodock M, Park H (2016) Assessment of factors contributing to health outcomes in the eight states of the Mississippi Delta Region. Prev Chronic Dis 13:E33. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150440

Zahnd WE, Jenkins WD, Mueller-Luckey GS (2017) Cancer mortality in the Mississippi Delta Region: descriptive epidemiology and needed future research and interventions. J Health Care Poor Underserved 28(1):315–328. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0025

Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, Stubbs RW, Bertozzi-Villa A, Morozoff C et al (2017) Trends and patterns of disparities in cancer mortality among US counties, 1980-2014. JAMA 317(4):388–406. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.20324

DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A (2016) Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin 66(1):31–42. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21320

Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Katki HA (2014) Tracking and evaluating molecular tumor markers with cancer registry data: HER2 and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju093

Phipps A, Li CI (2010) Breast cancer biology and clinical characteristics. In: Li CI (ed) Breast cancer epidemiology. Springer, New York

Grann VR, Troxel AB, Zojwalla NJ, Jacobson JS, Hershman D, Neugut AI (2005) Hormone receptor status and survival in a population-based cohort of patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer 103(11):2241–2251. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21030

Akinyemiju T, Moore JX, Ojesina AI, Waterbor JW, Altekruse SF (2016) Racial disparities in individual breast cancer outcomes by hormone-receptor subtype, area-level socio-economic status and healthcare resources. Breast Cancer Res Treat 157(3):575–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3840-x

Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, Chen VW, Clarke CA, Ries LA et al (2014) US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju055

Llanos AA, Chandwani S, Bandera EV, Hirshfield KM, Lin Y, Ambrosone CB et al (2015) Associations between sociodemographic and clinicopathological factors and breast cancer subtypes in a population-based study. Cancer Causes Control 26(12):1737–1750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0667-4

Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, Jemal A, Ryerson AB, Henry KA et al (2015) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. J Natl Cancer Inst 107(6):djv048. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv048

Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V (2007) Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer 109(9):1721–1728. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22618

Trivers KF, Lund MJ, Porter PL, Liff JM, Flagg EW, Coates RJ et al (2009) The epidemiology of triple-negative breast cancer, including race. Cancer Causes Control 20(7):1071–1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9331-1

Sineshaw HM, Gaudet M, Ward EM, Flanders WD, Desantis C, Lin CC et al (2014) Association of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer subtypes in the National Cancer Data Base (2010-2011). Breast Cancer Res Treat 145(3):753–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2976-9

Akinyemiju TF, Pisu M, Waterbor JW, Altekruse SF (2015) Socioeconomic status and incidence of breast cancer by hormone receptor subtype. Springerplus 4:508. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1282-2

Vona-Davis L, Rose DP (2009) The influence of socioeconomic disparities on breast cancer tumor biology and prognosis: a review. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 18(6):883–893. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.1127

Dietze EC, Sistrunk C, Miranda-Carboni G, O’Regan R, Seewaldt VL (2015) Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: disparities versus biology. Nat Rev Cancer 15(4):248–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3896

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Shields AE (2016) Understanding and effectively addressing breast cancer in African American women: unpacking the social context. Cancer 122(14):2138–2149. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29935

SEER*Stat Database: NAACCR Incidence Data—CiNA Analytic File, 1995-2014, for NHIAv2 Origin, Custom File With County, Zahnd—Disparities in breast ca subtype (3-year increments) (which includes data from CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), CCCR’s Provincial and Territorial Registries, and the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registries), certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) as meeting high-quality incidence data standards for the specified time periods, submitted December 2016

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

United States Department of Agriculture. 2016 Rural Urban Continuum Codes. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation.aspx. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

National Cancer Institute. Mammography prevalence within 2 years (Age 40+)—small area estimates. https://sae.cancer.gov/nhis-brfss/estimates/mammography.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

Area Health Resources Files (AHRF). 2014-2015. Rockville, MD.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce

Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Dores GM, Sherman ME (2006) Comparison of age distribution patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15(10):1899–1905. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-06-0191

Phipps AI, Ichikawa L, Bowles EJA, Carney PA, Kerlikowske K et al (2010) Defining menopausal status in epidemiologic studies: a comparison of multiple approaches and their effects on breast cancer rates. Maturitas 67(1):60–66

Siu AL, United States Preventive Services Task Force (2016) Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 164(4):279–296. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-2886

Zahnd WE, McLafferty SL (2017) Contextual effects and cancer outcomes in the United States: a systematic review of characteristics in multilevel analyses. Ann Epidemiol 27(11):739–748

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R (2002) Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol 156(5):471–482

Akinyemiju TF, Genkinger JM, Farhat M, Wilson A, Gary-Webb TL, Tehranifar P (2015) Residential environment and breast cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 15:191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1098-z

Hall HI, Jamison PM, Coughlin SS, Uhler RJ (2004) Breast and cervical cancer screening among Mississippi Delta women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 15(3):375–389

Delta Regional Authority (2017) About. http://dra.gov/about-dra/mission-and-vision/. Accessed 9 Aug 2017

Moss JL, Liu B, Feuer EJ (2017) Urban/rural differences in breast and cervical cancer incidence: the mediating roles of socioeconomic status and provider density. Womens Health Issues 27(6):683–691

Palmer JR, Viscidi E, Troester MA, Hong CC, Schedin P, Bethea TN et al (2014) Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in African American women: results from the AMBER Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju237

Danielle K (2011) Cities where women are having the most babies. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2011/10/21/cities-where-women-are-having-the-most-babies. Accessed 10 Aug 2018

Shinde SS, Forman MR, Kuerer HM, Yan K, Peintinger F, Hunt KK et al (2010) Higher parity and shorter breastfeeding duration: association with triple-negative phenotype of breast cancer. Cancer 116(21):4933–4943. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25443

Islami F, Liu Y, Jemal A, Zhou J, Weiderpass E, Colditz G et al (2015) Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 26(12):2398–2407. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv379

DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A (2014) Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 64(1):52–62. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21203

Taylor TR, Williams CD, Makambi KH, Mouton C, Harrell JP, Cozier Y et al (2007) Racial discrimination and breast cancer incidence in US Black women: the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 166(1):46–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm056

Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J (2006) “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health 96(5):826–833. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2004.060749

Geronimus AT, Hicken MT, Pearson JA, Seashols SJ, Brown KL, Cruz TD (2010) Do US black women experience stress-related accelerated biological aging?: a novel theory and first population-based test of black-white differences in telomere length. Hum Nat 21(1):19–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-010-9078-0

Linnenbringer E, Gehlert S, Geronimus AT (2017) Black-White disparities in breast cancer subtype: the intersection of socially patterned stress and genetic expression. AIMS Public Health 4(5):526–556. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2017.5.526

Hébert JR, Braun KL, Kaholokula JK, Armstead CA, Burch JA, Thompson B (2015) Considering the role of stress in populations of high-risk, underserved community networks program centers. Prog Community Health Partnersh 9:71–82

Krieger N, Jahn JL, Waterman PD (2017) Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992-2012. Cancer Causes Control 28(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2

Finerman R, Williams C, Bennett L (2010) Health disparities and engaged medical anthropology in the United States Mid-South. Urban Anthropol Stud Cult Syst World Econ Dev 39(3):265–297

Boscoe FP, Sherman C (2006) On socioeconomic gradients in cancer registry data quality. J Epidemiol Community Health 60(6):551

Krieger N, Chen JT, Ware JH, Kaddour A (2008) Race/ethnicity and breast cancer estrogen receptor status: impact of class, missing data, and modeling assumptions. Cancer Causes Control 19(10):1305–1318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-008-9202-1

Howlader N, Noone AM, Yu M, Cronin KA (2012) Use of imputed population-based cancer registry data as a method of accounting for missing information: application to estrogen receptor status for breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 176(4):347–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr512

Institute of Medicine National Cancer Policy Forum (2009) Ensuring quality cancer care through the oncology workforce: sustaining care in the 21st century: workshop summary. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Meilleur A, Subramanian SV, Plascak JJ, Fisher JL, Paskett ED, Lamont EB (2013) Rural residence and cancer outcomes in the United States: issues and challenges. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22(10):1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-13-0404

Acknowledgments

These data are based on the NAACCR December 2015 data submission. Support for cancer registries is provided by the state, province, or territory in which the registry is located. In the U.S., registries also participate in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) or both. In Canada, all registries submit data to the Canadian Cancer Registry maintained by Statistics Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zahnd, W.E., Sherman, R.L., Klonoff-Cohen, H. et al. Disparities in breast cancer subtypes among women in the lower Mississippi Delta Region states. Cancer Causes Control 30, 591–601 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01168-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01168-0