Abstract

Newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men (NHMSM) are at high risk of mental health problems but may also develop post-traumatic growth (PTG). According to the Common Sense Model, illness perception (including both cognitive representation and emotional representation) affects coping and health-related outcomes. A cross-sectional survey was conducted to examine the associations between illness perception and PTG among 225 NHMSM in Chengdu, China. Linear regression analyses indicated that the constructs of emotional representation subscale (β = −0.49) and five cognitive representation subscales (timeline, consequence, identity, attribution to god’s punishment/will, and attribution to chance/luck) (β = −0.13 to −0.37) were negative correlates of PTG, while four other constructs of cognitive representation (coherence, treatment control, personal control, and attribution to carelessness) were positive correlates (β = 0.15 to 0.51). No moderating effects were observed. The associations between five cognitive representation subscales and PTG were fully-mediated via emotional representation. The results indicate that interventions promoting PTG among NHMSM are warranted and should alter illness perception, emotional representation in particular. Future studies should clarify relationships between cognitive representation and emotional representation, and extend similar research to other health-related outcomes and HIV-positive populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health problems are prevalent among people living with HIV (PLWH) [1, 2]. It is evident that such problems were positively associated with risk behaviors [3] and disease progression [1, 2], and negatively associated with self-care and service seeking behaviors [4, 5]. It also increased the likelihood of HIV transmissions [6] among PLWH. A large segment of PLWH consists of men who have sex with men (MSM). For instance, 40% of the 437,000 PLWH reported in China in 2013 were MSM [7].

HIV-positive MSM are highly vulnerable to mental health problems. The World Health Organization pointed out that MSM in general showed higher prevalence of psychological problems but lower prevalence of mental health service utilization than other men [8]. As expected, the prevalence of psychological problems was even higher among HIV-positive MSM than MSM and PLWH in general [9], as HIV-positive MSM face numerous stressors and double stigma toward both PLWH and MSM [10]. The prevalence of suicidal ideation among HIV-positive MSM ranged from 28 to 59% in the U.S. [11, 12] and was 31% in China [13], while that of depression ranged from 42.9 to 55.8% in China [13, 14]. However, related preventive and treatment services targeting HIV-positive MSM are warranted but not readily available [15,16,17].

For various reasons, mental health issues among newly diagnosed HIV-positive MSM (NHMSM) require special attention. First, NHMSM are taking up a new disease identity. Second, they are in the initial phase of adjustment and the initial coping strategies adopted may have lasting effects on their mental and physical health outcomes [18]. Third, they are forming their perceptions related to HIV; such evolving perceptions may have lasting effects on mental health. Fourth, it is a critical time period for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [18] and post-traumatic growth (PTG). Thus, early mental health interventions targeting NHMSM may have significant long-term effects.

Despite the importance, there is a dearth of studies in literature investigating mental health problems among NHMSM. There are seven quantitative studies and two qualitative studies investigating mental health of NHMSM [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Six of them were conducted in China [20,21,22,23, 26, 27], two studies were conducted in the U.S. [19, 24], and one was conducted in Australia [25]. They were based on seven independent samples [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Four studies reported the prevalence of depression (22.8–36% in mainland China and 22.2% in Australia) and/or anxiety (28.5–42.0% in mainland China) [21,22,23, 25]. One of these studies investigated links between understandings about adversity and different outcomes, including PTG [20]. None of these studies involved illness perception.

While traditional psychology focuses on abnormality, positive psychology emphasizes the positive aspects of mental health and personal growth [28]. PTG, an important topic in positive psychology, is defined as positive changes as a result of struggling with a traumatic event [29]. Individuals who experience PTG would perceive benefits in three broad domains: changes in self-perception (e.g., greater sense of personal strength), changes in interpersonal relations (e.g., more intimate relationships with others), and changes in their philosophy of life (e.g., recognition of new possibilities or paths for one’s life and spiritual development) [30]. PTG can co-exist with PTSD [31,32,33,34,35]. It was negatively associated with suicidal ideation [35, 36] and psychological distress [36,37,38], and positively associated with optimism [39], positive affect, self-efficacy, resilience and social support [40,41,42,43]. One meta-analysis reported that PTG improved physical and mental health among cancer patients and PLWH [29]. Interventions can effectively promote PTG [44] and hence potentially alleviate mental health problems indirectly. Validated measurements [45, 46] are available to assess PTG, and have been applied to Chinese survivors of accidental injury, cancer, coronary heart diseases, and SARS [31, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43]. To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated PTG among PLWH living in China [47, 48].

How patients perceive illnesses may affect the development of PTG. The processing of trauma-related cognitions (e.g., appraisal, adaptation, and meaning-making) is a potential mechanism for formation of PTG [30, 49]. Illness perception is defined as patients’ beliefs and expectations about an illness or related somatic symptoms [50]. It includes cognitive representation and emotional representation, which are the key components of the Common Sense Model, also known as the Illness Perception Model or Self-regulatory Model [51, 52]. The model (Fig. 1) postulates that illness stimuli caused by a health threat (e.g., HIV-positive diagnosis) would induce cognitive and emotional representations. Such representations would influence coping strategies to determine illness outcomes (e.g., disease status) and emotional outcomes (e.g., emotional distress), respectively, in two parallel and inter-related processes. Through appraisals of such health-related outcomes, the individual would also update the illness stimuli of the health threat. The model (part or full) has been applied to study diseases such as cardiovascular, metabolic and cancer [53], as well as HIV/AIDS [54,55,56].

It is not our purpose to test the Common Sense Model, which is beyond the scope of the study. The model is an important one as it provides researchers with a strong rationale to study important potential associations between cognitive/emotional representations and health-related outcomes. Empirically, our study and many others have investigated such associations without testing the mediating effects of coping strategies and the part on appraisal, nor testing the entire model. Examples of these studies included those that focused on health-related outcomes such as functional adaptation, help-seeking behaviors, and adherence to medical recommendations [55, 57,58,59]. A meta-analysis further showed that the two types of cognitive representations were associated with depression, anxiety, distress, worry, negative affect and intrusion [60].

A literature search on PubMed using keywords “illness perception” and “China” found 22 published papers that applied illness perception to understand various health-related outcomes [61, 62]. Although such studies did not focus on PLWH in China, some of them targeted PLWH of other countries. To our knowledge, no study has targeted NHMSM in any country. Like PTG, illness perception can be modified by interventions [63,64,65]. To our knowledge, no study has investigated PTG among NHMSM and its relationship with illness perception.

As seen from Fig. 1, the self-regulation adaptation consists of two partially parallel processes that involve cognitive and emotional representations, and they interact with each other to determine one’s coping strategies and health-related outcomes [66]. It implies that strong negative emotional representation may compromise the positive impact and/or inflate the negative impact of cognitive representation on PTG. To our knowledge, no study has tested such a moderation hypothesis. Furthermore, the cognitive theory of emotions posits that cognitive processes influence emotional responses [67]. Specifically, cognitive beliefs about a disease can affect one’s emotional response towards the disease [67]. The Common Sense Model [51, 52], supported by empirical findings, also suggests that constructs of cognitive representation and emotional representation are significantly correlated with each other [68,69,70]. It is possible that the association between cognitive representation and PTG may be mediated via emotional representation. Although several studies suggested that emotional representation and cognitive representation showed independent impact on health outcomes such as quality of life, emotion and stress [71,72,73], no study has tested this mediation hypothesis explicitly. For the first time, the mediation and moderation hypotheses were tested in this study.

We investigated associations between the two constructs of illness perception (cognitive representation and emotional representation) and PTG among NHMSM. Following other studies, we defined NHMSM as MSM who were confirmed as HIV-positive during the last 12 months [74,75,76,77,78,79]. We further tested the two hypotheses, that emotional representation would interact with cognitive representation to affect PTG, and that emotional representation would mediate the associations between constructs of cognitive representation and PTG.

Method

Study Design and Data Collection

Inclusion criteria were (1) Chinese men aged 16 or above, (2) confirmed as HIV-positive in the last 12 months, and (3) anal intercourse with at least one man in the last year. We collaborated with the largest non-governmental organization (NGO) providing HIV prevention and care services to PLWH and MSM in Chengdu, Sichuan province, China, which has a population size of about 10 million. There were 70,000 MSM living in Chengdu (2011) [80], and their HIV prevalence was 15.0% in 2010 [81] and 26.2% in 2013 [82].

Recruitment procedures were as follows: (1) Six staff of the NGO went through the service records and contacted all the NGO’s service users who were HIV-positive MSM through phone calls or social media or during their visits, or participants’ referrals. (2) During the contact, the staff asked a few screening questions to identify NHMSM who were eligible to join the study (n = 282), according to the inclusion criteria. (3) These 282 prospective participants were briefed about the study, and were informed that refusals would not affect their right to use any services and they could quit any time without being questioned. (4) With written informed consent, anonymous face-to-face interviews were conducted in a private room at the NGO. (5) Out of the 282 NHMSM contacted by the staff, 57 (20.2%) were refusals and 225 (79.8%) consented and completed the study. (6) Participants received a monetary compensation (50 RMB or 7.8 USD) for their time spent.

Measurements

Background Variables

Background information collected included socio-demographic characteristics, permanent resident status of Chengdu, duration of stay in Chengdu, and sexual orientation. HIV-related information [date of HIV diagnosis, CD4 count found in the last episode of testing, and use of antiretroviral treatment (ART)] was recorded. The background characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 1.

PTG

The PTG scale was based on Milam’s [39] work targeting PLWH. Participants were asked to report whether they had experienced positive or negative changes with regards to various dimensions of their life. The response categories were from 1 (highly negative change) to 5 (highly positive change), with 3 = no change [39]. After consulting some NHMSM, two (out of 11) items on spirituality were omitted due to low cultural relevance. Sample items included “appreciation for the value of your own life” and “your own inner strength” (see Table 2 for all items). In this study, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) extracted one factor that explained 64.1% of the variance [KMO test = 0.84; Bartlett’s test = 933.8 (p < 0.001)]. All items were used in data analyses. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Illness Perception

The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire for HIV (IPQ-R-HIV) was used in this study. The original scale measured one dimension of emotional representation and seven dimensions of cognitive representation [identity, timeline acute/chronic, consequences, personal control, treatment control, illness coherence (perceived understanding of the illness), and timeline cyclical] [83]. We omitted the timeline-cyclical subscale as HIV infection was a widely known chronic condition. An additional dimension of cognitive representation (i.e., causal attribution) was assessed by seven items adapted from Reynolds’ work [58]; they measured six subscales [god’s punishment (two items), carelessness, being deceived, unaware of the risk, chance/luck, and substance use]. All items were assessed with responses from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The ER subscale consisted of six items that assessed negative emotions towards HIV (e.g., “Having HIV makes me feel angry”, “Having HIV makes me feel afraid”, and “When I think about having HIV I get upset). The number of items for each of the subscales is listed in Table 3. All the subscales used in this study were translated into Chinese and back-translated into English by two bilingual health workers to ensure linguistic equivalence. Feedback obtained from a pilot study of 11 HIV-positive MSM was used to finalize the questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Multiple linear regression models were fit using the PTG as the dependent variable and IPQ-R-HIV subscales as the independent variables, adjusted for background variables having p < 0.10 in the univariate analysis. All variables with p < 0.10 obtained in such an analysis were used as candidates for fitting a forward stepwise multiple linear regression model (entry: p < 0.10; removal: p > 0.20). The SPSS for Windows software package (version 16.0) was used for statistical analyses; p < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant and 0.05 < p < 0.10 was considered marginally statistically significant.

To test the moderation hypothesis, product terms (emotional representation × a subscale of cognitive representation) were created and added to the main-effect model to assess improvement in goodness-of-fit (by assessing changes in F-values) of the hierarchical models involved. According to Baron and Kenny [84], emotional representation mediates the association between a particular subscale of cognitive representation and PTG, only if (1) it is associated with both PTG scale and the CR subscale, and (2) the subscale of cognitive representation is associated with PTG. For each subscale of cognitive representation fulfilling such requirements, the subscale of emotional representation was added to the model containing the cognitive representation subscale of interest as the independent variable and PTG as the dependent variable (adjusted for significant background variables). Full or partial mediation effect would have been detected if the original significant regression coefficient became non-significant or remained significant but substantially diminished, respectively.

Results

Background Characteristics

Of the 225 participants, about half (53.8%) were aged 30 or below (mean = 32.2; SD = 10.5; range 17–71 years), possessed a college degree (44.4%), were full time workers (62.2%), and had a monthly income > 000 RMB (about 312 USD) (48%). Over 2/3 (69.8%) had lived in Chengdu for ≥2 years but only 36% possessed permanent residency status. About 3/4 (72.0%) self-reported as homosexuals. Two-thirds (66.7%) were currently single or divorced and 1/3 (33.3%) were currently married or cohabiting with a woman. About 2/3 (61.8%) had their HIV diagnosed during the last 6 months (mean duration = 5.64 months; SD = 3.76 months). About 1/3 (31.1%) obtained a CD4 count <350 cells/ml (last episode of testing); 20.4% were currently on ART.

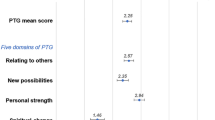

Attributes of PTG and IPQ-R-HIV

Over 40% endorsed a positive or strongly positive change regarding the PTG scale items that were related to closeness with family/friends, compassion for others, priority in life and importance in life; 25–40% showed such positive changes regarding willingness to express emotions, ability in handling difficulties, involvement in interesting things, and inner strength (see Table 2). There were also 6.2–48.9% giving item responses reflecting negative changes. The overall mean PTG scale score was 27.68 (SD = 7.31, range 9–45). Descriptive statistics of the IPQ-R-HIV subscales are summarized in Table 3.

Factors of PTG

Negative associations were found between age >30 years old and PTG (p = 0.008), and between having lived in Chengdu and PTG (p = 0.078) (see Table 4). The results of the bivariate analysis involving emotional representation and cognitive representation are summarized in Table 4. The Emotional Representation subscale and nine out of the 12 cognitive representation subscales showed statistically significant correlations with PTG. The absolute values of the significant correlation coefficients ranged from 0.13 to 0.51 (see Table 5). The three non-significant cognitive representation variables were attrition to deception, lack of awareness and attrition to substance use (r ranged from 0.01 to 0.08; p > 0.05).

In the main adjusted multiple linear regression analysis (also shown in Table 4), negatively associated factors of PTG included the Emotional Representation subscale (β = −0.49) and five cognitive representation subscales [timeline (β = −0.32), consequence (β = −0.37), identity (β = −0.20), attribution to god’s punishment/will (β = −0.23), and attribution to chance/luck (β = −0.13)]; positive associations involved four cognitive representation subscales [treatment control (β = 0.48), illness coherence (β = 0.32), personal control (β = 0.51) and attribution to carelessness (β = 0.15)] (see Table 5).

Using those variables that were significant in the adjusted analysis as candidates, a forward stepwise multiple regression model identified three significant subscales that were independently associated with PTG: emotional representation (β = −0.63), identity (β = −0.82); and attribution to carelessness (β = 0.99) (entry: p < 0.10, removal: p > 0.20; R square = 0.553). To avoid repetition, these statistics are not shown in the tables.

Testing Moderating Effects

No significant moderation effect was detected as none of the interaction terms involving the subscales of cognitive representation and Emotional Representation subscale was statistically significant (data were not shown in the tables).

Testing Mediation Effects

Since three subscales of cognitive representation that were significantly associated with PTG were not significantly correlated with emotional representation [personal control (Spearman r = −0.115, p = 0.085), identity (Spearman r = 0.126, p = 0.060) and attrition to chance/luck (Spearman r = 0.032, p = 0.636)], the mediation requirements were not all fulfilled and hence ER could not mediate their associations with PTG. The other six subscales of cognitive representation (i.e., illness coherence, timeline, consequence, attribution to god’s punishment/will, and attribution to chance/luck) were significantly associated with emotional representation (Spearman correlation coefficients ranged from −0.46 to 0.75, p < 0.05); their mediation hypotheses were tested in Table 5. The results show that five out of these six cognitive representation subscales became statistically non-significant after adjusting for both emotional representation and the significant background variables; their associations with PTG were hence fully mediated by emotional representation. Partial mediation via ER was detected for the association between treatment control and PTG, as the β of treatment control remained statistically significant but diminished from 0.21 to 0.13 after adding emotional representation to the model (Table 6).

Discussion

PTG has no cut-off point as it is a spectrum reflecting extent of changes. Participants showed multi-facet PTG (e.g., closeness with family/friends, compassion with others, priority and importance in life). It is important to understand that such growth might have already occurred within the first half and maintained in the second half of the first year since HIV diagnosis, as duration since HIV diagnosis (i.e., <6 vs ≥6 months) was not significantly associated with PTG. Hence, interventions fostering PTG among NHMSM should start early. Longitudinal studies are required to test this conjecture and track changes in level of PTG among NHMSM over time

We found that younger age (≤30 years old) was associated with PTG. Segmentation by age should be considered when designing related interventions, as those targeting younger NHMSM may be more effective in promoting PTG. About two-thirds (64%) of the participants were internal migrants (i.e., no permanent residency status of Chengdu). Although permanent residency status of a city was associated with depression and anxiety among HIV-positive MSM [85], it was not significantly associated with PTG among our sampled NHMSM.

As contextual background, according to the national guideline used at the time when the study was conducted [86], PLWH with CD4 level <350 cells/ml should be given free ART. However, only 2/3 of our participants fulfilling that condition were taking up ART. This might be partially related to the policy that PLWH need to receive ART in their hometowns while many participants were internal migrants and were hence ineligible to receive free ART. In a previous study, availability of ART was significantly associated with depression among NHMSM [26]. In contrast, this study showed that treatment status was not significantly associated with PTG. Since not all participants showed low CD4 counts (<350 cells/ml), some of those who were not on treatment were having higher CD4 counts and hence better health conditions. The treatment variable used in this study thus did not fully represent an unmet demand, although factors of PTG might be different from those of psychological problems [87]. Such mixture of CD4 levels and treatment eligibility might partially explain the non-significance of the association between treatment status and PTG. Also, PTG might be less affected by unfavorable conditions as positive psychology is involved. Further meta-analysis is warranted to test this contention.

The hypotheses that cognitive/emotional representation correlate with PTG were mostly supported by our data. In the adjusted analysis, constructs of cognitive representation including treatment control, personal control and illness coherence were positively associated with PTG. As treatment control involves questions about perceptions on efficacy of ART, it is applicable to all participants, disregarding their treatment status. Personal control may increase self-efficacy and treatment control may increase level of hopefulness, both self-efficacy and hopefulness are protective against mental health problems [88, 89]. To make use of such findings for promotion of PTG among NHMSM, we should enhance sense of personal control and treatment control by affirming beliefs on effectiveness and importance of self-care and ART. Illness coherence refers to the perceived level of understanding of the disease [83]. Hence, relevance of technical concepts such as CD4, viral load and viral suppression, drug adherence, drug resistance, treatment effectiveness, side effects, curability and other issues should be explained to NHMSM in lay languages.

Furthermore, five constructs of cognitive representation were negatively associated with PTG (time-line, consequence, identity, attribution to god’s punishment/will, and attribution to chance). Such findings are also implicative. Whilst we cannot deny the negative consequences of HIV, we should persuade NHMSM through interventions that PLWH can live a reasonably normal life given advancements in ART, and guide them to recognize and appreciate some possible positive consequences, such as those that they have acknowledged. Interventions should help participants to convince themselves that HIV is a chronic disease which is caused by a bio-behavioral process of viral infection, and assist them to accept HIV as part of their daily life, and enhance positive coping. To counteract the negative association between identity (number of symptoms self-perceived as being caused by HIV) and PTG, we should clarify that some of those symptoms that they reported might not have been caused by HIV. It is also interesting to know that attribution to god’s punishment/will and chance might diminish PTG. A study showed that attributions of HIV infection to destiny/higher power and others’ responsibility were associated with lower self-esteem and avoidance coping among Asians [90]. Such external attributions might result in a sense of helplessness and lower control over the disease and its associated consequences, reducing active and positive coping among PLWH [91]. Attribution results from an individual’s social-cognitive processing, and people from collectivistic cultures like Chinese are more likely to attribute adverse events to others, the context, and fate [92]. Future studies may look at cultural differences involving attributions and their impact on PTG.

Our data support the Common Sense Model that, besides the constructs of cognitive representation, emotional representation is an important potential determinant of PTG. In fact, the absolute size of the standardized regression coefficients (β) of emotional representation was found to be the largest one (0.49), followed by that of the cognitive representation construct of consequences (0.37), while those of the other constructs of cognitive representation only ranged from 0.13 to 0.23. Therefore, although nine of the illness perception constructs were significantly correlated with PTG, we found that negative emotional representation and perceived negative HIV/AIDS-related consequences were the two strongest potential barriers inhibiting PTG among NHMSM.

Interventions promoting PTG among PLWH should focus on both types of representations. It is important for health workers to recognize that cognitive and emotional representations have shown to be modifiable [63,64,65], and such modifications can potentially improve PTG among PLWH. Our literature review however, found no study reporting interventions for promotion of PTG among PLWH, although such interventions are warranted.

An important finding is that emotional representation has particular relevance in promoting PTG among PLWH. First, the construct showed the strongest β amongst all illness perception constructs. Second, such a strong association has particular implications on intervention for enhancement of PTG among NHMSM, as emotional representation of NHMSM is newly formed and strong. We should facilitate NHMSM to understand and manage their negative emotions caused by their newly formed HIV status effectively, and to foster corresponding positive coping.

Furthermore, according to the Common Sense Model, interventions for promotion of PTG among NHMSM should foster effective strategies to cope with HIV-related cognitive and emotional representations and related stressors. Such interventions should also enhance social support, especially emotional support, in order to buffer negative emotional representation’s potential compromising effect on PTG [93].

It is not the purpose of this study to investigate the associations between cognitive/emotional representation and mental health problems (e.g., anxiety and depression). Some studies have reported such associations [94,95,96]. Interventions that focused on reduction of anxiety and depression among PLWH have involved various approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy [97, 98], stress-coping [99], and positive psychology attributes such as resilience and mindfulness [100, 101]. To our knowledge, such mental health interventions targeting PLWH have not explicitly considered modification of specific HIV-related emotional representation, although some of them have focused on improving emotions and moods in general. Future RCT studies may investigate efficacy of interventions based on cognitive and emotional representations in reducing mental health problems such as depression and anxiety among HIV-positive MSM and other types of PLWH. Overall, our findings have shed light on a new direction of research and intervention.

It is a novel finding that out of the seven significant associations between CR subscales and PTG that fulfilled the requirements for testing the hypothesis of emotional representation being a potential mediator, five (i.e., illness coherence, timeline, consequence, attribution to god’s punishment/will, and attribution to chance/luck) of such associations were fully mediated and two (treatment control and identity) were partially mediated by emotional representation. It suggests that some cognitive representation constructs might increase/reduce emotional representation, which may in turn facilitate/prohibit PTG. Thus, interventions based on cognitive representation can potentially promote PTG indirectly through changes in emotional representations. Personal control and attribution to carelessness were associated with PTG but not with emotional representation. Their effects on PTG were hence independent from that of emotional representation, possibly because unlike other constructs of cognitive representation, they are less likely to initiate strong emotions. The moderation hypothesis suggested by the Common Sense Model was however, not supported by our data. To our knowledge, no other study has tested such a moderation hypothesis. Our findings on mediations and moderations highlight new research directions for refining the theory. Future research should confirm the inter-relationships between emotional/cognitive representation and health-related behaviors and outcomes.

Our findings are preliminary in a way, as we only looked at a very special psychological outcome (i.e., PTG). Relationships between cognitive/emotional representation and other important outcomes (e.g., mental health problems, coping style, risk behaviors, healthy life style, service seeking, and drug adherence) should also be investigated to inform interventions and confirm/improve the Common Sense Model. As mentioned, a number of studies have looked at such outcomes in the context of other diseases [55, 57,58,59]. We chose to look at the relationship between emotional/cognitive representation and PTG as most of the studies have looked at negative psychological problems (e.g., depression). Yet, we believe that positive psychology has an important but under-developed role to play in understanding and improving mental health among NHMSM.

The study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted only in one Chinese city; generalization to other cities or the nation should be made with caution. As the sample involved NHMSM, limited generalization can be made to other HIV-positive MSM or non-MSM HIV-positive populations. Second, as there was no sampling frame and random sampling was not feasible, selection bias may have occurred. Third, the 12-month definition of NHMSM was arbitrary although other studies used similar definitions [74,75,76,77,78,79]. Fourth, reporting bias might exist as it is socially desirable to endorse positive changes. Fifth, PTG is a continuous process and our data was unable to capture a dynamic process. The observed relationships were based on cross-sectional data and we cannot establish a causal relationship between illness perception and PTG. Sixth, the cognitive representation variables are correlated with each other and hence would cause co-linearity when entered into the same model. We hence did not fit such a model but instead, fit a stepwise forward regression model that contained variables that were independently associated with PTG. Seventh, we did not test the entire Common Sense Model. Lastly, the mediation hypotheses were also not mentioned in the original model and the theory behind such mediations needs to be further established. We are suggesting a new research direction largely based on empirical results, instead of testing the entire theory.

In conclusion, it is evident that PTG can occur among NHMSM, even within the first 6 or 12 months since one’s HIV diagnosis. Constructs of illness perception (emotional representation and many constructs of cognitive representation) were significantly associated with PTG. The results therefore largely support the Common Sense Model, which has been widely applied to other disease groups. We found that emotional representation did not interact with constructs of cognitive representation to influence PTG. Instead, most of the associations between the constructs of cognitive representation (e.g., illness coherence and attribution to god’s punishment/will) and PTG were fully mediated via emotional representation. Furthermore, the associations between emotional representation/consequences and PTG were especially strong. Therefore, emotional representation plays a very important role in the relationships between illness perception and PTG. However, cognitive representation still has a role to play as some variables of cognitive representation have independent effects on PTG. Furthermore, an interesting and novel conclusion is that cognitive representation’s effect on PTG may largely go through (mediated by) emotional representation. The findings suggest new research directions to understand more about the joint roles of emotional representation and cognitive representation in affecting coping and disease outcomes among NHMSM, other types of PLWH, and even other disease groups. The relationship between cognitive/emotional representation and PTG may vary across socio-demographic groups; future studies may look at such variations. It is also possible to cultivate PTG by changing illness perception through interventions. Pilot studies considering our findings are greatly warranted.

References

Perry S, Fishman B. Depression and HIV. How does one affect the other? JAMA. 1993;270(21):2609–10.

Schuster R, Bornovalova M, Hunt E. The influence of depression on the progression of HIV: direct and indirect effects. Behav Modif. 2012;36(2):123–45.

Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA. Seropositive urban men’s study T. Correlates of sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(5):383–400.

Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):291–307.

Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdottir TB, Richter C, et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:142.

Tsai AC, Burns BF. Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:26–35.

National Health and Family Planning Commission of The People’s Republic of China. 2014. China AIDS Response Progress Report. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2014.pdf. 2014.

World Health Organization. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender people: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Press; 2011.

Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Landrine H, Klein DJ, Sticklor LA. Perceived discrimination and mental health symptoms among Black men with HIV. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2011;17(3):295–302.

Wohl AR, Galvan FH, Carlos JA, Myers HF, Garland W, Witt MD, et al. A comparison of MSM stigma, HIV stigma and depression in HIV-positive Latino and African American men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1454–64.

Shelton AJ, Atkinson J, Risser JM, McCurdy SA, Useche B, Padgett PM. The prevalence of suicidal behaviours in a group of HIV-positive men. AIDS Care. 2006;18(6):574–6.

Carrico AW, Neilands TB, Johnson MO. Suicidal ideation is associated with HIV transmission risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(4):e3–4.

Wu YL, Yang HY, Wang J, Yao H, Zhao X, Chen J, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and associated factors among HIV-positive MSM in Anhui, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(7):496–503.

Li J, Mo PK, Wu AM, Lau JT. Roles of self-stigma, social support, and positive and negative affects as determinants of depressive symptoms among HIV infected men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):261–73.

Tao X, Gai R, Zhang N, Zheng W, Zhang X, Xu A, et al. HIV infection and mental health of “money boys”: a pilot study in Shandong Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(2):358–68.

Zhao Q, Li X, Kaljee LM, Fang X, Stanton B, Zhang L. AIDS orphanages in China: reality and challenges. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(4):297–303.

Sun YH, Sun L, Wu HY, Zhang ZK, Wang B, Yu C, et al. Loneliness, social support and family function of people living with HIV/AIDS in Anhui rural area, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(4):255–8.

Kelly B, Raphael B, Judd F, Perdices M, Kernutt G, Burnett P, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in response to HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(6):345–52.

Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Santos J, Watt MH, Wilson PA, et al. The development and feasibility of a brief risk reduction intervention for newly hiv-diagnosed men who have sex with men. J Clin Psychol. 2011;39(6):717–32.

Yu NX, Chen L, Ye Z, Li X, Lin D. Impacts of making sense of adversity on depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and posttraumatic growth among a sample of mainly newly diagnosed HIV-positive Chinese young homosexual men: the mediating role of resilience. AIDS Care. 2017;29(1):79–85.

Tao J, Wang L, Kipp AM, Qian HZ, Yin L, Ruan Y, et al. Relationship of stigma and depression among newly HIV-diagnosed Chinese men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):292–9.

Tao J, Qian HZ, Kipp AM, Ruan Y, Shepherd BE, Amico KR, et al. Effects of depression and anxiety on antiretroviral therapy adherence among newly diagnosed HIV-infected Chinese MSM. AIDS. 2017;31(3):401–6.

Tao J, Vermund SH, Lu H, Ruan Y, Shepherd BE, Kipp AM, et al. Impact of depression and anxiety on initiation of antiretroviral therapy among men who have sex with men with newly diagnosed HIV infections in China. AIDS Patient Care. 2017;31(2):96–104.

Abler L, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Kochman A. Depression and HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care. 2015;29(10):550–8.

Prestage G, Brown G, Allan B, Ellard J, Down I. Impact of peer support on behavior change among newly diagnosed Australian gay men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(5):565–71.

Li HH, Holroyd E, Lau J, Li X. Stigma, subsistence, intimacy, face, filial piety, and mental health problems among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in China. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(4):454–63.

Li H, Tucker J, Holroyd E, Zhang J, Jiang B. Suicidal ideation, resilience, and healthcare implications for newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men in China: a qualitative study. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;46:1–10.

Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology—an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5–14.

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Field AP. Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):436–47.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1–18.

Ho SM, Chan MW, Yau TK, Yeung RM. Relationships between explanatory style, posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese breast cancer patients. Psychol Health. 2011;26(3):269–85.

Wu K, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Zhou P, Wei C. Coexistence and different determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among Chinese survivors after earthquake: role of resilience and rumination. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1043.

Xu J, Liao Q. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic growth among adult survivors 1 year following 2008 Sichuan earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1–2):274–80.

Zhou X, Wu X, Chen J. Longitudinal linkages between posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors following the Wenchuan earthquake in China: a three-wave, cross-lagged study. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(1):107–11.

Yu XN, Lau JT, Zhang J, Mak WW, Choi KC, Lui WW, et al. Posttraumatic growth and reduced suicidal ideation among adolescents at month 1 after the Sichuan Earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1–3):327–31.

Gallaway MS, Millikan AM, Bell MR. The association between deployment-related posttraumatic growth among U.S. Army soldiers and negative behavioral health conditions. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(12):1151–60.

Cheng SK, Chong GH, Chang SS, Wong CW, Wong CS, Wong MT, et al. Adjustment to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): roles of appraisal and post-traumatic growth. Psychol Health. 2006;21(3):301–17.

Liu JE, Wang HY, Wang ML, Su YL, Wang PL. Posttraumatic growth and psychological distress in Chinese early-stage breast cancer survivors: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2014;23(4):437–43.

Milam JE. Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(11):2353–76.

Chan IW, Lai JC, Wong KW. Resilience is associated with better recovery in Chinese people diagnosed with coronary heart disease. Psychol Health. 2006;21(3):335–49.

Dong C, Gong S, Jiang L, Deng G, Liu X. Posttraumatic growth within the first 3 months after accidental injury in China: the role of self-disclosure, cognitive processing, and psychosocial resources. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(2):154–64.

Mo PK, Lau JT, Yu X, Gu J. The role of social support on resilience, posttraumatic growth, hopelessness, and depression among children of HIV-infected parents in mainland China. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1526–33.

Yu Y, Peng L, Tang T, Chen L, Li M, Wang T. Effects of emotion regulation and general self-efficacy on posttraumatic growth in Chinese cancer survivors: assessing the mediating effect of positive affect. Psychooncology. 2014;23(4):473–8.

Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20(1):20–32.

Bates GW, Trajstman SE, Jackson CA. Internal consistency, test-retest reliability and sex differences on the posttraumatic growth inventory in an Australian sample with trauma. Psychol Rep. 2004;94(3 Pt 1):793–4.

Taku K, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The factor structure of the posttraumatic growth inventory: a comparison of five models using confirmatory factor analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(2):158–64.

Zhang J, Zhao G, Li X, Hong Y, Fang X, Barnett D, et al. Positive future orientation as a mediator between traumatic events and mental health among children affected by HIV/AIDS in rural China. AIDS Care. 2009;21(12):1508–16.

Du H, Li X, Chi P, Zhao J, Zhao G. Relational self-esteem, psychological well-being, and social support in children affected by HIV. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(12):1568–78.

Park CL, Helgeson VS. Introduction to the special section: growth following highly stressful life events–current status and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):791–6.

Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–63.

Diefenbach MA, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of illness representation: theoretical and practical considerations. J Soc Distress Homeless. 1996;5(1):11–38.

Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA, Miller LP, et al. Illness representations: theoretical foundations. In: Weinman J, Petrie K, editors. Perceptions of health and illness. London: Harwood Publishers; 1997. p. 19–46.

Brzoska P, Yilmaz-Aslan Y, Sultanoglu E, Sultanoglu B, Razum O. The factor structure of the Turkish version of the revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R) in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:852.

Reynolds N, Sanzero EL, Nicholas P, Corless I, Kirksey K, Hamilton M, et al. HIV illness representation as a predictor of self-care management and health outcomes: a multi-site. Cross-cult Stud AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):258–67.

Kemppainen J, Kim-Godwin YS, Reynolds NR, Spencer VS. Beliefs about HIV disease and medication adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS in rural southeastern North Carolina. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(2):127–36.

Catunda C, Seidl EMF, Lemétayer F. Illness perception and quality of life of HIV-positive persons: mediation effects of tenacious and flexible goal pursuit. Psychol Health Med. 2016;22:1–9.

Rajpura J, Nayak R. Medication adherence in a sample of elderly suffering from hypertension: evaluating the influence of illness perceptions, treatment beliefs, and illness burden. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):58–65.

Reynolds NR, Eller LS, Nicholas PK, Corless IB, Kirksey K, Hamilton MJ, et al. HIV illness representation as a predictor of self-care management and health outcomes: a multi-site, cross-cultural study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):258–67.

Broadbent E, Donkin L, Stroh JC. Illness and treatment perceptions are associated with adherence to medications, diet, and exercise in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):338–40.

Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analysis review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(2):141–84.

Ji H, Zhang L, Li L, Gong G, Cao Z, Zhang J, et al. Illness perception in Chinese adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;128:94–101.

Yu NL, Tan H, Song ZQ, Yang XC. Illness perception in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata in China. J Psychosom Res. 2016;86:1–6.

Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Campbell MJ, Carey ME, Cradock S, et al. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):491–5.

Keogh KM, Smith SM, White P, McGilloway S, Kelly A, Gibney J, et al. Psychological family intervention for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(2):105–13.

Glattacker M, Heyduck K, Meffert C. Illness beliefs, treatment beliefs and information needs as starting points for patient information—evaluation of an intervention for patients with chronic back pain. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):378–89.

Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16:143–66.

Lazarus RS. Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. Am Psychol. 1982;37(9):1019.

Fan SY, Eiser C, Ho MC, Lin CY. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the mediation effects of illness perceptions and coping. Psychooncology. 2013;22(6):1353–60.

Sriprasong S, Hanucharurnkul S, Panpukdee O, Krittayaphong R, Pongthavornkamol K, Vorapongsathorn T. Functional status model: an empirical test among discharged acute myocardial infarction patients. Thai J Nurs Res. 2010;13(4):268–84.

Rozema H, Vollink T, Lechner L. The role of illness representations in coping and health of patients treated for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(8):849–57.

Knibb RC, Horton SL. Can illness perceptions and coping predict psychological distress amongst allergy sufferers? Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 1):103–19.

Hagger MS, Orbell S. Illness representations and emotion in people with abnormal screening results. Psychol Health. 2006;21(2):183–209.

Gómez-de-Regil L, Kwapil TR, Barrantes-Vidal N. Illness perception mediates the effect of illness course on the quality of life of Mexican patients with psychosis. Appl Res Qual Life. 2014;9(1):99–112.

Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Jeffries R, Javanbakht M, Drumright LN, Daar ES, et al. Behaviors of recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men in the year postdiagnosis: effects of drug use and partner types. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(2):176–82.

Smith DM, Drumright LN, Frost SD, Cheng WS, Espitia S, Daar ES, et al. Characteristics of recently HIV-infected men who use the Internet to find male sex partners and sexual practices with those partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(5):582–7.

Drumright LN, Strathdee SA, Little SJ, Araneta MR, Slymen DJ, Malcarne VL, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use before and after HIV diagnosis among recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):401–7.

Gorbach PM, Drumright LN, Daar ES, Little SJ. Transmission behaviors of recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(1):80–5.

Truong HM, Kellogg T, Schwarcz S, Delgado V, Grant RM, Louie B, et al. Frequent international travel by men who have sex with men recently diagnosed with HIV-1: potential for transmission of primary HIV-1 drug resistance. J Travel Med. 2008;15(6):454–6.

Ghanem A, Little SJ, Drumright L, Liu L, Morris S, Garfein RS. High-risk behaviors associated with injection drug use among recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men in San Diego, CA. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1561–9.

Duan Z, Fan S, Lu R, Wu X, Shi Y, Li Z, et al. Consistently high HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Chengdu city from 2009 to 2014. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(12):1057–62.

CGCO. Chengdu Gay Care Organization (CGCO) Annual Report of 2009. Chengdu: Chengdu Gay Care Organization. 2010.

Song D, Zhang H, Wang J, Liu Q, Wang X, Operario D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection and unrecognized HIV status among men who have sex with men and women in Chengdu and Guangzhou, China. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2395–404.

Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie K, Horne R, Cameron L, Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82.

Li J, Mo PK, Kahler CW, Lau JT, Du M, Dai Y, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Care. 2015;28:1–6.

Zhang F, Haberer JE, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma Y, Zhao D, et al. The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: challenges and responses. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S143–8.

Pollard C, Kennedy P. A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: a 10-year review. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12(3):347–62.

Luszczynska A, Gutierrez-Dona B, Schwarzer R. General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: evidence from five countries. Int J Psychol. 2005;40(2):80–9.

Arnau RC, Rosen DH, Finch JF, Rhudy JL, Fortunato VJ. Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: a latent variable analysis. J Pers. 2007;75(1):43–64.

Chou CC, Chronister J, Chou CH, Tan S, Macewicz T. Responsibility attribution of HIV infection and coping among injection drug users in Malaysia. AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1551–8.

Vassend O, Eskild A. Psychological distress, coping, and disease progression in HIV-positive homosexual men. J Health Psychol. 1998;3(2):243–57.

Carpenter S. Effects of cultural tightness and collectivism on self-concept and causal attributions. Cross Cult Res. 2000;34(1):38–56.

Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):1038–46.

Juergens MC, Seekatz B, Moosdorf RG, Petrie KJ, Rief W. Illness beliefs before cardiac surgery predict disability, quality of life, and depression 3 months later. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(6):553–60.

Hepgul N, Pariante CM, Baraldi S, Borsini A, Bufalino C, Russell A, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients receiving interferon-alpha: the role of illness perceptions. J Health Psychol. 2016. doi:10.1177/1359105316658967.

Rutter CL, Rutter DR. Illness representation, coping and outcome in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):377–91.

Himelhoch S, Medoff D, Maxfield J, Dihmes S, Dixon L, Robinson C, et al. Telephone based cognitive behavioral therapy targeting major depression among urban dwelling, low income people living with HIV/AIDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2756–64.

Safren SA, O’cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, Mayer KH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):1–10.

Brown JL, Vanable PA. Cognitive–behavioral stress management interventions for persons living with HIV: a review and critique of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(1):26–40.

Yu X, Lau JT, Mak WW, Cheng Y, Lv Y, Zhang J. A pilot theory–based intervention to improve resilience, psychosocial well-being, and quality of life among people living with HIV in rural China. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40(1):1–16.

Masomzadeh K, Moradi A, Parhoon H, Parhoon K, Mirmotahari M. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based Stress reduction (MBSR) on anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in patients with HIV/AIDS. Int J Behav Sci. 2017;10(3):129–34.

Funding

This study is supported by internal funding of Centre for Health Behaviours Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, the Chinese University of Hong Kong and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, J.T.F., Wu, X., Wu, A.M.S. et al. Relationships Between Illness Perception and Post-traumatic Growth Among Newly Diagnosed HIV-Positive Men Who have Sex with Men in China. AIDS Behav 22, 1885–1898 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1874-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1874-7