Abstract

Background

Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a key predictor of the success of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatment, and is potentially amenable to intervention. Insight into predictors or correlates of non-adherence to ART may help guide targets for the development of adherence-enhancing interventions. Our objective was to review evidence on predictors/correlates of adherence to ART, and to aggregate findings into quantitative estimates of their impact on adherence.

Methods

We searched PubMed for original English-language papers, published between 1996 and June 2014, and the reference lists of all relevant articles found. Studies reporting on predictors/correlates of adherence of adults prescribed ART for chronic HIV infection were included without restriction to adherence assessment method, study design or geographical location. Two researchers independently extracted the data from the same papers. Random effects models with inverse variance weights were used to aggregate findings into pooled effects estimates with 95% confidence intervals. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was used as the common effect size. The impact of study design features (adherence assessment method, study design, and the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) of the country in which the study was set) was investigated using categorical mixed effects meta-regression.

Results

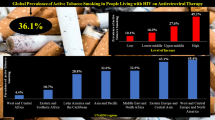

In total, 207 studies were included. The following predictors/correlates were most strongly associated with adherence: adherence self-efficacy (SMD = 0.603, P = 0.001), current substance use (SMD = -0.395, P = 0.001), concerns about ART (SMD = -0.388, P = 0.001), beliefs about the necessity/utility of ART (SMD = 0.357, P = 0.001), trust/satisfaction with the HIV care provider (SMD = 0.377, P = 0.001), depressive symptoms (SMD = -0.305, P = 0.001), stigma about HIV (SMD = -0.282, P = 0.001), and social support (SMD = 0.237, P = 0.001). Smaller but significant associations were observed for the following being prescribed a protease inhibitor-containing regimen (SMD = -0.196, P = 0.001), daily dosing frequency (SMD = -0.193, P = 0.001), financial constraints (SMD -0.187, P = 0.001) and pill burden (SMD = -0.124, P = 0.001). Higher trust/satisfaction with the HIV care provider, a lower daily dosing frequency, and fewer depressive symptoms were more strongly related with higher adherence in low and medium HDI countries than in high HDI countries.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that adherence-enhancing interventions should particularly target psychological factors such as self-efficacy and concerns/beliefs about the efficacy and safety of ART. Moreover, these findings suggest that simplification of regimens might have smaller but significant effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a key predictor of antiretroviral treatment success, and is potentially amenable to intervention [1]. Sufficiently high levels of adherence to ART are necessary to achieve and sustain viral suppression and to prevent disease progression and death [2], yet, many patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)do not succeed in achieving or maintaining adequate levels of adherence to ART [3].

Insight into predictors or correlates of non-adherence to ART offers the potential to identify patients at risk for low levels of adherence. This would enable healthcare providers to target those patients in most need, and to tailor their care appropriately. Moreover, knowledge of predictors/correlates of non-adherence to ART may help guide targets for the development of interventions to enhance or maintain adherence to ART.

Medication adherence is considered to be a complex behavior that is influenced by a wide range of factors, which have previously been categorized into sociodemographic, condition-related, treatment-related, patient-related, and interpersonal factors [4],[5]. In recent years, a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated predictors/correlates of adherence by patients prescribed ART for chronic HIV infection. One systematic review provided a comprehensive assessment of predictors/correlates of adherence to ART, but did not aggregate findings into quantitative estimates of their effect on adherence [5]. A number of other reviews did aggregate findings into quantitative estimates, but focused only on patient-reported barriers and facilitators [1], sociodemographic factors [3], clinical, comorbid, and treatment-related factors [6] and depression [7], or investigated a particular patient population, such as drug users [8].

The objective of the present study was to carry out a comprehensive review into the current research evidence on sociodemographic, treatment-related, condition-related, patient-related, and interpersonal predictors and correlates of adherence to ART, and to aggregate the findings into quantitative estimates of their impact on adherence. Thereby, we aimed to assess the relative importance of each predictor/correlate of adherence. Studies on adherence to ART have been conducted in a variety of countries and settings, and have used a variety of research designs and adherence measurement methods. For these reasons, another aim was to assess the impact of such study design features on predictors/correlates of adherence.

Methods

Our meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines [9]. Two of the authors (NL and PN) searched PubMed for papers published from August 1996 to June 2014 using the following strategy: Search: (((((“adult”[MeSH Terms] AND hasabstract[text] AND ( “1996/01/01”[PDat] : “2014/06/10”[PDat] ))) AND ((“patient compliance”[MeSH Terms] OR “medication adherence”[MeSH Terms] AND hiv) AND hasabstract[text] AND ( “1996/01/01”[PDat] : “2014/06/10”[PDat] ))) AND hasabstract[text] AND ( “1996/01/01”[PDat] : “2014/06/10”[PDat] ))) NOT children[MeSH Terms] Filters: Abstract available, From 1996/01/01 to 2014/06/10. Additionally, the reference lists of the papers retrieved were reviewed for additional publications. Eligible studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) original research study, 2) written in English, 3) reporting on adult (older than 16 years of age) patients infected with HIV who 4) were being prescribed self-administered ART for chronic HIV infection, 5) using a quantitative method to assess adherence to ART, and 6) reporting a statistical association between a potential predictor/correlate and adherence. No geographical restrictions were applied. We excluded studies that focused exclusively on the following specific populations: drug users, prison inmates, homeless individuals, and patients with psychiatric disorders.

We considered the following sociodemographic predictors/correlates of adherence: age, sex, and financial constraints. Financial constraints were defined as being unemployed or having an income level in the lowest category as defined within a particular study. Treatment-related predictors/correlates were: duration of ART, number of prescribed antiretroviral pills per day (that is, pill burden), daily dosing frequency, and whether or not the regimen contained a protease inhibitor (PI). Disease-related predictors/correlates included CD4 cell count and time since HIV diagnosis. We also investigated interpersonal predictors/correlates: social support, HIV stigma and trust or satisfaction with the HIV care provider. Finally, patient-related predictors/correlates were current substance use (alcohol and drugs), depressive symptoms, adherence self-efficacy (the extent to which patients believe that they will be able to adhere), motivation to adhere, locus of control (the extent to which individuals believe that they can control events that affect them), concerns about adverse effects of ART, and beliefs in the necessity or utility of ART.

Two authors (NL and PN) independently extracted data from each study that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, using a scoring sheet. The following information was extracted: name of the first author, year of publication, sample size, country in which the study was conducted, year study was started, adherence assessment method (self-report, electronic monitoring devices (EMD), pharmacy refill, pill count), and whether patients were initiating, restarting, or switching an ART regimen, or were already on ART, and the potential predictors or correlates of adherence. Factors that were assessed at the same time as the adherence measurement were considered to be correlates, and factors assessed prior to the adherence measurement were considered to be predictors. Because we included studies conducted in any country around the world, we categorized countries according to the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) [10] during the year the study was started into low (HDI ≤ 0.50), medium (HDI of 0.50 to 0.79), and high (HDI ≥ 0.80) development countries.

When data from the same study were reported in multiple publications, we selected the publication that had the largest sample size and/or reported the largest number of predictors/correlates. If the study evaluated adherence at multiple time points, the value of the first measurement was used to avoid dependence. When relationships between predictors/correlates and adherence were reported for discrete subgroups within a single study, the groups were included as independent samples.

The quality of the reporting of the included studies was assessed using the 22 items recommended by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [11]. Items fulfilling the STROBE statement were considered positive and items not fulfilling the statement were as-considered negative.

Statistical analysis

We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) as the common effect size to express the magnitude of the association between predictors/correlates and adherence. If studies did not provide the SMD, we calculated it from r, correlation coefficient means and standard deviations, odds ratios, t-test, χ2 test, or F-statistic, contingency table data, or exact P values [12]. When studies reported an insignificant association without data, we assigned it an SMD of 0.001. We adjusted the SMD using the small sample size bias correction prior to analysis. SMD values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were interpreted as small, medium. and large effects, respectively [13].

Predictors/correlates were selected for quantitative pooling if 10 or more independent effect sizes could be calculated. Random effect models with inverse variance weights were used to aggregate individual effect sizes into pooled effect estimates with 95% confidence limits (CI), using the SPSS macro MeanES from Lipsey and Wilson [12],[14].

We examined whether the effect sizes differed significantly across levels of potential moderators of the predictor-adherence relationship, if there was heterogeneity across studies (I2 > 50%) and sufficient data (k > 4 in each subgroup) to support these analyses [15]. The following study design features were investigated as potential moderators: whether the factor was a predictor or correlate, whether the adherence assessment method was self-report (versus all other methods) or EMD (versus all others), whether the study was conducted in a high HDI country (versus medium and low HDI country), and whether patients were already on ART (versus initiating, restarting, or switching ART). For the moderator analyses, subgroup analyses were performed by grouping effect sizes by study design feature and assessing heterogeneity between groups using the between-group Q statistic (Q-between) within a mixed effects model using the method of moments estimation. If Q-between is significantly greater than the heterogeneity within groups due to error (Q-within), this indicates that a moderator variable explains a significant proportion of the total heterogeneity in effect sizes. The moderator analyses were conducted using the SPSS macro MetaF from Lipsey and Wilson [12],[14].

Results

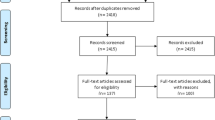

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. In total, 207 studies were included in our analysis, reporting on 103,836 patients [16]-[222]. Two hundred studies consisted of one independent sample for calculating effect sizes, five studies consisted of two samples and two studies consisted of three samples, resulting in a total of 216 independent samples (k = 216). A total of 67% (k = 145) of the samples reported on correlates of adherence, and 33% (k = 71) on predictors. A total of 54% (k = 117) of the samples included patients already on ART and 46% (k = 99) included patients who were (re)starting or switching. The following adherence assessment methods were used: 77% self-report (k = 166), 11% EMD (k = 23), 8% (k = 18) a pharmacy refill-based measure and 4% (k = 9) a pill count-based measure. A total of 67% (k = 145) of the samples originated from countries with a high HDI, 19% (k = 40) from countries with a medium HDI, and 14% (k = 31) from countries with a low HDI. For characteristics of the included studies, see Additional file 1.

Locus of control and motivation to adhere were excluded from our analysis because fewer than 10 independent effect sizes could be calculated for these two predictors/correlates.

The strongest association with adherence was found for the predictor/correlate adherence self-efficacy, with the pooled effect size being medium to large (SMD = 0.603, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.73, k = 39, P = 0.001; Figure 2 (1.1.1)). The following predictors/correlates were significantly associated with adherence, with their effect sizes being small to medium: current substance use (SMD = -0.395, 95% CI -0.49 to -0.30, k = 80, P = 0.001), concerns about ART (SMD = -0.389, 95% CI -0.53 to -0.25, k = 14, P = 0.001), trust/satisfaction with the HIV healthcare provider (SMD = 0.377, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.46, k = 30, P = 0.001), beliefs about the necessity/utility of ART (SMD = 0.357, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.49, k = 25, p = 0.001), depressive symptoms (SMD = -0.305, 95% CI -0.35 to -0.26, k = 90, P = 0.001), HIV stigma (SMD = -0.282, 95% CI -0.36 to -0.21, k = 47, P = 0.001) and social support (SMD = 0.237, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.29, k = 67, P = 0.001). The predictors/correlates yielding small to medium effects are shown in Figure 2 (1.1.2).

The following predictors/correlates were significantly associated with adherence with their effect sizes being small: being prescribed a PI-containing regimen (SMD = -0.196, 95% CI -0.27 to -0.12, k = 26, P = 0.001), daily dosing frequency (SMD = -0.193, 95% CI -0.25 to -0.14, k = 29, P = 0.001) and financial constraints (SMD = -0.187, 95% CI -0.24 to -0.14, k = 110, P = 0.001). The predictors/correlates with small effect sizes are shown in Figure 2 (1.1.3).

The following predictors/correlates were significantly associated with adherence but their effect sizes were very small: pill burden (SMD = -0.124, 95% CI -0.18 to -0.07, k = 57, P = 0.001), age (SMD = 0.118, 95% CI 0.089 to 0.147, k = 158, P = 0.001), time since HIV diagnosis (SMD = -0.116, 95% CI -0.17 to -0.06, k = 57, P = 0.001) and male gender (SMD = 0.081, 95% CI 0.037 to 0.12, k = 142, P = 0.001). The predictors/correlates with very small effect sizes are shown in Figure 2 (1.1.4). Two predictors/correlates were not significantly associated with adherence: CD4 cell count (SMD = -0.015, 95% CI -0.079 to 0.048, k = 67, P = 0.64) and duration of ART (SMD = 0.003, 95% CI -0.047 to 0.052, k = 51, P = 0.92).

For forest plots of the individual studies examining predictors/correlates, see Additional file 2. For the scoring of included studies according to the items of the STROBE statement, see Additional file 3.

The study design feature “HDI of the country in which the study was conducted” was significantly associated with four predictors/correlates. Trust/satisfaction with the HIV care provider was more strongly associated with adherence in countries with a low or medium HDI than in countries with a high HDI (Figure 3 (1.2.3); Q-between = 8.04, P = 0.005). Daily dosing frequency was more strongly and negatively associated with adherence in countries with a medium or low HDI than in countries with a high HDI (Figure 3 (1.2.2); Q-between = 3.88, P = 0.049). Older age was associated with higher adherence in countries with a high HDI but not in countries with a medium or low HDI (Figure 3 (1.2.1); Q-between = 5.16, P = 0.02). Depressive symptoms were more strongly associated with lower levels of adherence in countries with a medium or low HDI than in countries with a high HDI (Figure 3 (1.2.4); Q-between = 4,38, P = 0.04).

The adherence assessment method was significantly associated with two predictors/correlates. Adherence self-efficacy was more strongly associated with adherence in studies using self-report as adherence assessment method than in studies using another method (Figure 4 (1.3.2); Q-between = 6.94, P = 0.008). Older age was more strongly associated with adherence in studies using EMD as adherence assessment method than in studies using another method (Figure 4 (1.3.1); Q-between = 10.12, P = 0.002).

Whether investigated factors were predictors or correlates yielded two significant associations. Trust/satisfaction with the HIV care provider was more strongly related with adherence if assessed as a correlate than if assessed as a predictor (Figure 4 (1.3.4); Q-between =7.44, P = 006). Current substance use was more strongly and negatively related with adherence if assessed as a correlate than as a predictor (Figure 4 (1.3.3); Q-between = 6.34, P = 0.012).

Discussion

In our meta-analysis based on 207 papers reporting on 103,836 patients, we obtained a comprehensive overview of the relative importance of various predictors/correlates of adherence to ART. Adherence to ART was most strongly associated with patients’ beliefs, that is, adherence self-efficacy beliefs, concerns about adverse effects of ART, and beliefs about the necessity/utility of ART, and also with current substance use, trust or satisfaction with the HIV care provider, depressive symptoms, HIV stigma, and social support. Aspects of regimen complexity, such as daily dosing frequency, pill burden, and whether the regimen included a PI, had smaller, albeit significant effects.

Our findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis of patients with various long-term medical conditions, showing that patients’ beliefs have an important influence on medication adherence [223]. Results are also consistent with previous studies showing that substance use, depressive symptoms, and HIV stigma are associated with lower levels of adherence, and trust or satisfaction with the healthcare provider are associated with higher levels of adherence [7],[8],[180],[224]. These results should be encouraging to HIV care providers, as they suggest several avenues for intervention that could result in improved adherence. In particular, patients’ adherence-related beliefs and the relationship between the patient and their HIV care provider are factors that are in principle modifiable, and thus possible targets for adherence-enhancing interventions. Eliciting and addressing patients' beliefs and promoting an improved relationship between patient and healthcare provider have previously been associated with improved levels of adherence [225],[226].

This study has several limitations. We aimed to provide a global overview of the relative importance of various predictors/correlates of adherence to ART. Therefore, several predictors/correlates were aggregated into broad categories, for example, social support, HIV stigma, trust or satisfaction with the HIV healthcare provider, financial constraints, and substance use. Within these broad categories, distinct types of predictors/correlates may have a different impact on adherence, which would have remained undetected in the present global analysis; for example, alcohol use could have a different impact on adherence compared with cocaine use.

Another limitation is that the search was performed using a single database (PubMed) only, and included only published English-language papers. This may have influenced our results.

However, this meta-analysis has also several strengths. It provides a comprehensive overview of predictors/correlates of adherence to ART, with quantitative estimates of their impact. Moreover, this meta-analysis provides information about the relative importance of predictors/correlates.

Papers were included without restriction to geographical region, adherence assessment method, or study design. This probably resulted in a consequently large heterogeneity in effect sizes for most predictors/correlates. Guidelines for the reporting of meta-analyses of observational studies have recommended using broad inclusion criteria and then performing analyses relating design features to outcomes [227]. We thus conducted meta-regression analyses to explore the impact of study design features on predictors/correlates of adherence.

The study design feature “HDI of the country in which the study was conducted” was significantly associated with four predictors/correlates. Trust/satisfaction with the HIV healthcare provider had a stronger positive effect on adherence in countries with a low or medium HDI than in countries with a high HDI. A possible explanation for this is that in countries with low or medium HDI, patients are more dependent on their HIV healthcare provider for information, support, and care. Conversely, in countries with a high HDI, patients usually have more extensive access to healthcare providers and to information about health, HIV, and ART, making them less dependent on their HIV healthcare provider. There could also be cultural differences in the relationship between patients and healthcare providers, with the healthcare providers having more authority in low or medium income countries.

Daily dosing frequency was more strongly and negatively associated with adherence in countries with a medium or low HDI than in countries with a high HDI. One possible explanation is that achieving or maintaining high levels of adherence is more challenging in low or medium HDI countries. The added challenge of more frequent daily dosing could therefore more easily result in lower levels of adherence in these countries. However, this explanation is in contrast to results from previous studies showing higher levels of adherence in low income countries than in high income countries [3],[228].

Older age was associated with higher adherence in countries with a high HDI but not in countries with a medium or low HDI. This finding could simply reflect the fact that studies from low and medium HDI countries included few older patients. Finally, depressive symptoms were more strongly and negatively associated with adherence in countries with a medium or low HDI than in countries with a high HDI.

A remarkable finding was the limited effect of the adherence assessment method on effect sizes. Self-reports are known to overestimate adherence. We expected to find stronger associations between predictors/correlates and adherence in studies using EMDs than in studies using self-reports because EMDs are usually considered to be a more valid adherence assessment method [229]. A possible explanation for the limited effect of the adherence assessment method could be that although self-reports overestimate adherence, the rank order of patients on an adherence scale is similar for self-report and electronic monitoring, thus yielding similar associations.

Duration of ART was not related to adherence in the present meta-analysis. It is usually assumed that adherence declines with increasing length time on treatment. However, a recent study investigating the natural history of changes in adherence to ART over time has shown that the decline is non-linear, with substantial heterogeneity across studies [230]. In view of these results and the fact that the present meta-analysis included both patients already on ART and patients (re)starting ART, the absence of a relation between duration of ART and adherence is not surprising.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis of predictor/correlates of ART showed that adherence was strongly related to patients’ adherence-related beliefs. These findings suggest that adherence-enhancing interventions should target psychological factors such as self-efficacy and necessity/concerns beliefs about ART. Additionally, simplification of regimens may have smaller, albeit significant effects.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. NL and PN performed database searches, study selection, and data extraction. NL performed quality assessment. PN conducted the meta-analyses and the moderator analyses. All authors reviewed and interpreted the study findings. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version before submission.

Additional files

References

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, Wilson K, Buchan I, Gill CJ, Cooper C: Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e438.

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, Moss A: Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001, 15: 1181-1183.

Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Llorca J, Sevilla L, Santos P, Rodríguez E, Warren MR, Vejo J: Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15: 1381-1396.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T: Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353: 487-497.

Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, Castelli F, Narciso P, Noto P, Vecchiet J, D’Arminio Moforte A, Wu AW, Antorini A: Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002, 31: S123-S127.

Atkinson MJ, Petrozzino JJ: An evidence-based review of treatment-related determinants of patients’ nonadherence to HIV medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009, 23: 903-914.

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA: Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011, 58: 181-187.

Malta M, Magnanini MM, Strathdee SA, Bastos FI: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14: 731-747.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6: e1000097.

United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports. []. Accessed September 2013., [http://hdr.undp.org]

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 147: 573-577.

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB: Practical Meta-Analysis. 2001, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 1988, Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Wilson DB: Meta-analysis macros for SPSS (version 2005.05.23). []. Accessed September 2013., [http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/ma.html]

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR: Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2009, Wiley, Chichester, UK

Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF, Fakande I: The effect of psychological distress on medication adherence in persons with HIV infection in Nigeria. Psychosom. 2010, 51: 68-73.

Alakija Kazeem S, Fadeyi A, Ogunmodede JA, Desalu O: Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral medication in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2010, 9: 191-195.

Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, Girma B, Deribe K: Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 265.

Andrade AS, Deutsch R, Celano S, Duarte NA, Marcotte TD, Umlauf A, Atkinson JH, McCutchan JA, Franklin D, Alexander TJ, McArthur JC, Marra C, Grant I, Collier AC: Relationships among neurocognitive status, medication adherence measured by pharmacy refill records, and virologic suppression in HIV-infected persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013, 62: 282-292.

Ammassari A, Antorine A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, Monforte AD, Wu AW, Starace F: Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosom. 2004, 45: 394-402.

Anuradha S, Joshi A, Negi M, Neeraj N, Rajeshwari K, Dewan R: Factors influencing adherence to ART: new insights from a center providing free ART under the national program in Delhi, India. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2013, 12: 195-201.

Aragonés C, Sánchez L, Campos JR, Pérez J: Antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons with HIV/AIDS in Cuba. MEDICC Review. 2011, 13: 17-21.

Arrivillaga M, Ross M, Useche B, Alzate ML, Correa D: Social position, gender role, and treatment adherence among Colombian women living with HIV/AIDS: social determinants of health approach. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009, 26: 502-510.

Babson KA, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO: HIV medication adherence and HIV symptom severity: the roles of sleep quality and memory. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013, 27: 544-552.

Barclay TR, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Mason KI, Reinhard MJ, Marion SD, Levine AJ, Durvasula RS: Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV-positive adults: health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychol. 2007, 26: 40-49.

Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD: Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV?. J gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 661-665.

Bell DJ, Kapitao Y, Sikwese R, van Oosterhout JJ, Lalloo DG: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients receiving free treatment from a government hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 45: 560-563.

Berhe N, Tegabu D, Alemayehu M: Effect of nutritional factors on adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults: a case control study in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013, 13: 233-doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-233

Bianco JA, Heckman TG, Sutton M, Watakakosol R, Lovejoy T: Predicting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected older adults: the moderating role of gender. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15: 1437-1446.

Birbeck GL, Kvalsund MP, Byers PA, Bradbury R, Mang’ombe C, Organek N, Kaile T, Sinyama AM, Sinyangwe SS, Malama K, Malama C: Neuropsychiatric and socioeconomic status impact antiretroviral adherence and mortality in rural Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011, 85: 782-789.

Blackstock OJ, Addison DN, Brennan JS, Alao OA: Trust in primary care providers and antiretroviral adherence in an urban HIV clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012, 23: 88-98.

Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL: The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10: 253-261.

der Kolk IM DB-v, Sprangers MA, van der Ende M, Schreij G, de Wolf F, Nieuwkerk PT: Lower perceived necessity of HAART predicts lower treatment adherence and worse virological response in the ATHENA cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 49: 460-462.

Bonolo PF, Cesar CC, Acurcio FA, Ceccato M, Acurcio FA, Ceccato M, de Padua CA, Alvares J, Campos LN, Carmo RA, Guimareaes MD: Non-adherence among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy: a challenge for health professionals in Brazil. AIDS. 2005, 19: S5-S13.

Bottonari KA, Tripathi SP, Fortney JC, Curran G, Rimland D, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Gifford AL, Pyne JM: Correlates of antiretroviral and antidepressant adherence among depressed HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012, 26: 265-273.

Boyer S, Clerc I, Bonono CR, Marcellin F, Bilé PC, Ventelou B: Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Soc Science Med. 2011, 72: 1383-1392.

Brigido LM, Rodrigues R, Casseb J, Oliveira D, Rossetti M, Menezes P, Duarte AJ: Impact of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected patients at a university public service in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001, 15: 587-593.

Brown JL, Littlewood RA, Vanable PA: Social-cognitive correlates of antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-infected individuals receiving infectious disease care in a medium-sized northeastern US city. AIDS Care. 2013, 25: 1149-1158.

Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Giordano TP: Impact of antiretroviral dosing frequency and pill burden on adherence among newly diagnosed, antiretroviral-naive HIV patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2012, 23: 351-355.

Cahn P, Vibhagool A, Schechter M, Soto-Ramirez L, Carosi G, Smaill F, Jordan JC, Pharo CE, Thomas NE, Steel HM: Predictors of adherence and virologic outcome in HIV-infected patients treated with abacavir- or indinavir-based triple combination HAART also containing lamivudine/zidovudine. Curr Med Res Opinion. 2004, 20: 1115-1123.

Cambiano V, Lampe FC, Rodger AJ, Smith CJ, Geretti AM, Lodwick RK, Puradiredja DI, Johnson M, Swaden L, Phillips AN: Long-term trends in adherence to antiretroviral therapy from start of HAART. AIDS. 2010, 24: 1153-1162.

Campbell JI, Ruano AL, Samayoa B, Estrado Muy DL, Arathoon E, Young B: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in an urban, free-care HIV clinic in Guatemala City, Guatemala. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2010, 9: 390-395.

Campos LN, Crosland Guimaraes MD, Remien RH: Anxiety and depression symptoms as risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14: 289-299.

Carballo E, Cadarso-Suárez C, Carrera I, Fraga J, de al Fuente J, Ocampo A, Oiea R, Prieto A: Assessing relationships between health-related quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Qual Life Res. 2004, 13: 587-599.

Cardarelli R, Weis S, Adams E, Radaford D, Vecino I, Munquia G, Johnson KL, Fulda KG: General health status and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2008, 7: 123-129.

Carmody ER, Diaz T, Starling P, Rocha Beruth dos Santos AP, Sacks HS: An evaluation of antiretroviral HIV/AIDS treatment in a Rio de Janeiro public clinic. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8: 378-385.

Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL: Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000, 19: 124-133.

Cauldbeck MB, O'Connor C, O'Connor MB, Saunders JA, Rao B, Mallesh VG, Praveen Kumar NK, Mamtha G, McGoldrick C, Laing RB, Satish KS: Adherence to anti-retroviral therapy among HIV patients in Bangalore, India. AIDS Res Ther. 2009, 6: 7.

Cha ES, Erlen JA, Kim KH, Sereika SM, Caruthers D: Mediating roles of medication-taking self-efficacy and depressive symptoms on self-reported medication adherence in persons with HIV: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008, 45: 1175-1184.

Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW: Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000, 12: 255-266.

Colbert AM, Sereika SM, Erlen JA: Functional health literacy, medication-taking self-efficacy and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Adv Nurs. 2013, 69: 295-304.

Cooper V, Horne R, Gellaitry G, Vrijens B, Lange AC, Fisher M, White D: The impact of once-nightly versus twice-daily dosing and baseline beliefs about HAART on adherence to efavirenz-based HAART over 48 weeks: the NOCTE study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 53: 369-377.

Cooper V, Moyle GJ, Fisher M, Reilly G, Ewan J, Liu HC, Horne R: Beliefs about antiretroviral therapy, treatment adherence and quality of life in a 48-week randomised study of continuation of zidovudine/lamivudine or switch to tenofovir DF/emtricitabine, each with efavirenz. AIDS Care. 2011, 23: 705-713.

Corless IB, Guarino AJ, Nicholas PK, Tver-Viola L, Kirksey K, Brion J, Dawson Rose C, Eller LS, Rivero-Mendez M, Kemppainen J, Nokes K, Sefcik E, Voss J, Wantland D, Johnson MO, Phillips JC, Webel A, Lipinge S, Portillo C, Chen WT, Maryland M, Hamilton MJ, Reid P, Hickey D, Holzemer WL, Sullivan KM: Mediators of antiretroviral adherence: a multisite international study. AIDS Care. 2013, 25: 364-377.

Dale S, Cohen M, Weber K, Cruise R, Kelso G, Brody L: Abuse and resilience in relation to HAART medication adherence and HIV viral load among women with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014, 28: 136-143.

Diabate S, Alary M, Koffi CK: Determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1-infected patients in Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2007, 21: 1799-1803.

DiIorio C, McCarty F, DePadilla L, Resnicow K, Holstad MM, Yeager K, Sharma SM, Morisky DE, Lundberg B: Adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens: a test of a psychosocial model. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13: 10-22.

Dlamini PS, Wantland D, Makoae LN, Chirwa M, Kohi TW, Greeff M, Naidoo J, Mullan J, Uys LR, Holzemer WL: HIV stigma and missed medications in HIV-positive people in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009, 23: 377-387.

Do NT, Phiri K, Bussmann H, Gaolathe T, Marlink RG, Wester CW: Psychosocial factors affecting medication adherence among HIV-1 infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in Botswana. AIDs Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010, 26: 685-691.

Dorz S, Lazzarini L, Cattelan A, Meneghetti F, Novara C, Concia E, Sica C, Sanavio E: Evaluation of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Italian HIV patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003, 17: 33-41.

Duggan JM, Locher A, Fink B, Okonta C, Chakraborty J: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a survey of factors associated with medication usage. AIDS Care. 2009, 21: 1141-1147.

Duong M, Piroth L, Grappin M, Forte F, Pevtavin G, Buisson M, Chavanet P, Porties H: Evaluation of the patient medication adherence questionnaire as a tool for self-reported adherence assessment in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral regimens. HIV Clin Trials. 2001, 2: 128-135.

Durante AJ, Bova CA, Fennie KP, Danvers KA, Holness DR, Burgess JD, Williams AB: Home-based study of anti-HIV drug regimen adherence among HIV-infected women: feasibility and preliminary results. AIDS Care. 2003, 15: 103-115.

Eholie SP, Tanon A, Polneau S, Ouiminga M, Djadji A, Kangah-Koffi C, Diakité N, Anglaret X, Kakou A, Bissagnené E: Field adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 45: 355-358.

Elul B, Basinga P, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Saito S, Horowitz D, Nash D, Mugabo J, Mugisha V, Rugigana E, Nkunda R, Asjimwe A: High levels of adherence and viral suppression in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy for 6, 12 and 18 months in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e53586.

Etard JF, Laniece I, Fall MB, Cilote V, Blazeiewski L, Diop K, Desclaux A, Ecochard R, Ndove I, Delaporte E: A 84-month follow up of adherence to HAART in a cohort of adult Senegalese patients. Trop Med Int Health. 2007, 12: 1191-1198.

Etienne M, Hossain M, Redfield R, Stafford K, Amoroso A: Indicators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy treatment among HIV/AIDS patients in 5 African countries. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2010, 9: 98-103.

Ettenhofer ML, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula R, Ullman J, Lam M, Myers H, Wright MJ, Foley J: Aging, neurocognition, and medication adherence in HIV infection. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 17: 281-290.

Falang KD, Akubaka P, Jimam NS: Patient factors impacting antiretroviral drug adherence in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012, 3: 138-142.

Farley J, Miller E, Zamani A, Tepper V, Morris C, Oyegunle M, Lin M, Charurat M, Blattner W: Screening for hazardous alcohol use and depressive symptomatology among HIV-infected in Nigeria: prevalence, predictors, and association with adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2010, 9: 218-226.

De Fatima Bonolo P, Ceccato M, Rocha GM, de Assis Acurcio F, Campos LN, Guimaraes MD: Gender differences in non-adherence among Brazilian patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013, 68: 612-620.

Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Safren SA, Mugavero MJ, Willig JH, Simoni JM, Wilson IB, Saag MS, Kitahata MM, Crane HM: Evaluation of the single-item self-rating adherence scale for use in routine clinical care of people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17: 307-318.

Ferguson TF, Stewart KE, Funkhouser E, Tolson J, Westfall AO, Saag MS: Patient-perceived barriers to antiretroviral adherence: associations with race. AIDS Care. 2002, 14: 607-617.

Finocchario-Kessler S, Catley D, Berkley-Patton J, Gerkovich M, Williams K, Banderas J, Goggin K: Baseline predictors of ninety percent or higher antiretroviral therapy adherence in a diverse urban sample: the role of patient autonomy and fatalistic religious beliefs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011, 25: 103-110.

Fong OW, Ho CF, Fung LY, Lee FK, Tse WH, Yuen CY, Sin KP, Wong KH: Determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Chinese HIV/AIDS patients. HIV Med. 2003, 4: 133-138.

Ford N, Darder M, Spelman T, Maclean E, Mills E, Boulle A: Early adherence to antiretroviral medication as a predictor of long-term HIV virological suppression: five-year follow up of an observational cohort. PLoSOne. 2010, 5: e10460.

Silva MCF, Ximenes RAA, Miranda Filho DB, Arraes LW, Mendes M, Melo AC, Fernandes PR: Risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Rev Inst Med trop S Paulo. 2009, 51: 135-139.

Frain MP, Bishop M, Tschopp MK, Ferrin MJ, Frain J: Adherence to medical regimens: understanding the effects of cognitive appraisal, quality of life, and perceived family resiliency. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2009, 52: 237-250.

Franke MF, Munoz M, Finnegan K, Zeladita J, Sebastian JL, Bavona JN, Shin SS: Validation and abbreviation of an HIV stigma scale in an adult spanish-speaking population in urban Peru. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14: 189-199.

Gao X, Nau DP, Rosenbluth SA, Scott V, Woodward C: The relationship of disease severity, health beliefs and medication adherence among HIV patients. AIDS Care. 2000, 12: 387-398.

Garcia R, Badaro R, Netto EM, Silva M, Amorin FS, Ramos A, Vaida F, Brites C, Schooley RT: Cross-sectional study to evaluate factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy by Brazilian HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006, 22: 1248-1252.

Gauchet A, Tarquinio C, Fischer G: Psychosocial predictors of medication adherence among persons living with HIV. Int J Behav Med. 2007, 14: 141-150.

Gay C, Portillo CJ, Kelly R, Coggins T, Davis H, Aouizerat BE, Pullinger CR, Lee KA: Self-reported medication adherence and symptom experience in adults with HIV. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care. 2011, 22: 257-268.

Gianotti N, Galli L, Bocchiola B, Cahua T, Panzini P, Zandona D, Salpietro S, Maillard M, Danise A, Pazzi A, Lazzarin A, Castagna A: Number of daily pills, dosing schedule, self-reported adherence and health status in 2010: a large cross-sectional study of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2013, 14: 153-160.

Gibbie T, Hay M, Hutchison CW, Mijch A: Depression, social support and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in people living with HIV/AIDS. Sex Health. 2007, 4: 227-232.

Giday A, Shiferaw W: Factors affecting adherence of antiretroviral treatment among AIDS patietns in an Ethiopian tertiary university teaching hospital. Ethiop Med J. 2010, 48: 187-194.

Gifford AL, Bormann JE, Shively MJ, Wright BC, Richman DD, Bozzette SA: Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000, 23: 386-395.

Glass TR, Battegay M, Cavassini M, De Geest S, Furrer H, Vernazza PL, Hirschel B, Bernasconi E, Rickenbach M, Günthard HF, Bucher HC: Longitudinal analysis of patterns and predictors of changes in self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 54: 197-203.

Godin G, Côté J, Naccache H, Lambert LD, Trottier S: Prediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A one-year longitudinal study. AIDS Care. 2005, 17: 493-504.

Gokarn A, Narkhede MG, Pardeshi GS, Doibale MK: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012, 60: 16-20.

Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, Miller LG, Beck CK, Ickovics J, Kaplan AH, Wenger NS: A prospecive studyof predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. Gen Intern Med. 2002, 17: 756-765.

Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Fernandez MI, Duran RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G, Isabel Fernandez M, Klimas NG, Schneiderman N: Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychol. 2004, 23: 413-418.

Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Llabre MM, Duran RE, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, Horne R: Physical symptoms, beliefs about medications, negative mood, and long-term HIV medication adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2007, 34: 46-55.

Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, González-Lahoz J: Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999, 13: 1763-1769.

Graham J, Bennett IM, Holmes WC, Gross R: Medication beliefs as mediators of the health literacy-antiretroviral adherence relationship in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007, 11: 385-392.

Hanif H, Bastors FI, Malta M, Bertoni N, Surkan PJ, Winch PJ, Kerrigan D: Individual and contextual factors of influence on adherence to antiretrovirals among people attending public clinics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13: 574-doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-574

Hansana V, Sanchaisuriva P, Durham J, Sychareun V, Chaleunvong K, Boonyaleepun S, Schelp FP: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among people living with HIV (PLHIV): a cross-sectional survey to measure in Lao PDR. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13: 617-doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-617

Haubrich RH, Little SJ, Currier JS, Forthal DN, Kemper CA, Beall GN, Johnson D, Dube MP, Hwang JY, McCutchan JA: The value of patient-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in predicting virologic and immunologic response. AIDS. 1999, 13: 1099-1107.

Heckman BD, Catz SL, Heckman TG, Miller JG, Kalichman SC: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in rural persons living with HIV disease in the United States. AIDS Care. 2004, 16: 219-230.

Holmes WC, Bilker WB, Wang H, Chapman J, Gross R: HIV/AIDS-specific quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 46: 323-327.

McDonnell Holstad MK, Pace JC, De AK, Ura DR: Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2006, 17: 4-15.

Holzemer WL, Corless IB, Nokes KM, Turner JG, Brown MA, Powell-Cope GM, Inouye J, Henry SB, Nicholas PK, Portillo CJ: Predictors of self-reported adherence in persons living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1999, 13: 185-197.

Horne R, Cooper V, Gellaitry G, Leake Date H, Fisher M: Patients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 45: 334-341.

Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Lo Y, Vlahov D, Rich JD, Schuman P, Stone VE, Smith DK, Schoenbaum EE: A prospective study of adherence and viral load in a large multi-center cohort of HIV-infected women. AIDS. 2002, 16: 2175-2182.

Huang L, Li L, Zhang Y, Li H, Li X, Wang H: Self-efficacy, medication adherence, and quality of life among people living with HIV in Hunan Province of China: a questionnaire survey. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013, 24: 145-153.

Huynh AK, Kinsler JJ, Cunningham WE, Sayles JN: The role of mental health in mediating the relationship between social support and optimal ART adherence. AIDS Care. 2013, 25: 1179-1184.

Ickovics JR, Cameron A, Zackin R, Bassett R, Chesney M, Johnson VA, Kuritzkes DR: Consequences and determinants of adherence to antiretroviral medication: results from adult AIDS clinical trials group protocol 370. Antivir Ther. 2002, 7: 185-193.

Ingersoll K: The impact of psychiatric symptoms, drug use, and medication regimen on non-adherence to HIV treatment. AIDS Care. 2004, 16: 199-211.

Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Bashi J, Aboubakrine M, Messou E, Maiga M, Traore HA, Zannou MD, Guehi C, Ba-Gomis FO, Minga A, Allou G, Eholie SP, Bissagnene E, Sasco AJ, Dabis F: Alcohol use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients in west Africa. Addiction. 2010, 105: 1416-1421.

Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E, Gore-Felton C, Goldsten RB, Wolfe H, Lightfoot M, Chesney MA: Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003, 17: 645-656.

Johnson MO, Dilworth SE, Taylor JM, Darbes LA, Comfort ML, Neilands TB: Primary relationships, HIV treatment adherence, and virologic control. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16: 1511-1521.

Juday T, Gupta S, Grimm K, Wagner S, Kim E: Factors associated with complete adherence to HIV combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin Trials. 2011, 12: 71-78.

Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB: Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the nutrition for healthy living study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 53: 266-272.

Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S: Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999, 14: 267-273.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D: HIV treatment adherence and unprotected sex practices in people receiving antiretroviral. Sex Transm Infect. 2003, 79: 59-61.

Kalichman SC, Pope H, White D, Cherry C, Amaral CM, Swetzes C, Flanagan J, Kalichman MO: Association between health literacy and HIV treatment adherence: further evidence from objectively measured medication adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2008, 7: 317-323.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T: Stress and poverty predictors of treatment adherence among people with low-literacy living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosom Med. 2010, 72: 810-816.

Kamau TM, Olson VG, Zipp GP, Clark MA: Coping self-efficacy as a predictor of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in men and women living with HIV in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011, 25: 557-561.

Kerr SJ, Avihingsanon A, Putcharoen O, Chetchotisakd P, Layton M, Ubolyam S, Ruxrungtham K, Cooper DA, Phanuphak P, Duncombe C: Assessing adherence in Thai patients taking combination antiretroviral therapy. Int J STD & AIDS. 2012, 23: 160-165.

King RM, Vidrine DJ, Danysh HE, Fletcher FE, McCurdy S, Arduino RC, Gritz ER: Factors associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012, 26: 479-485.

Kleeberger CA, Phair JP, Strathdee SA, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP: Determinants of heterogeneous adherence to HIV-antiretroviral therapies in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune defic Syndr. 2001, 26: 82-92.

Kumar V, Encinosa W: Effects of antidepressant treatment on antiretroviral regimen adherence among depressed HIV-infected patients. Psychiatr Q. 2009, 80: 131-141.

Kunutsor S, Evans M, Thoulass J, Walley J, Katabira E, Newell JN, Muchuro S, Balidawa H, Namagala E, Ikoona E: Ascertaining baseline levels of antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda: a multimethod approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 55: 221-224.

Kyser M, Buchacz K, Bush TJ, Conley LJ, Hammer J, Henry K, Kojic EM, Milam J, Overton ET, Wood KC, Brooks JT: Factors associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the SUN study. AIDS care. 2011, 23: 601-611.

Ladefoged K, Andersson M, Koch A, Rendal T, Rydbacken M: Living conditions, quality of life, adherence and treatment outcome in Greenlandic HIV patients. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012, 71: 18639.

Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, Anastos K, Ostrow DG, Witt MD, Jacobson LP: Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Diseases. 2007, 45: 1377-1385.

Leombruni P, Fassino S, Lavagnino L, Orofino G, Morosini P, Picardi A: The role of anger in adherence to highly active antiretroviral treatment in patients infected with HIV. Psychother Psychosom. 2009, 78: 254-257.

Leserman J, Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fordiani JM, Balbin E: Stressful life events and adherence in HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008, 22: 403-411.

Li L, Lee SJ, Wen Y, Lin C, Wan D, Jiraphongsa C: Antiretroviral therapy adherence among patients living with HIV/AIDS in Thailand. Nurs Health Sciences. 2010, 12: 212-220.

Li X, Huang L, Wang H, Fennie KP, He G, Williams AB: Stigma mediates the relationship between self-efficacy, medication adherence, and quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011, 25: 665-671.

Luszczynska A, Sarkar Y, Knoll N: Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2007, 66: 37-42.

Lyimo RA, Stutterheim SE, Hospers HJ, de Glee T, van der Ven A, de Bruin M: Stigma, disclosure, coping, and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Tanzania. AIDS patient Care STDs. 2014, 28: 98-105.

Lynam I, Catley D, Goggin K, Rabinowitz JL, Gerkovich MM, Williams K, Wright J: Autonomous regulation and locus of control as predictors of antiretroviral medication adherence. J Health Psychol. 2009, 14: 578.

Maggiolo F, Ripamonti D, Arici C, Gregis G, Quinzan G, Camacho GA, Ravasio L, Suter F: Simpler regimens may enhance adherence to antiretrovirals in HIV-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2002, 3: 371-378.

Malow R, Devieux JG, Stein JA, Rosenberg R, Jean-Gilles M, Attonito J, Koenig SP, Raviola G, Sévère P, Pape JW: Depression, substance abuse and other contextual predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among Haitians. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17: 1221-1230.

Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M: The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2002, 34: 1115-1121.

Maqutu D, Zewotir T, North D, Naidoo K, Grobler A: Determinants of optimal adherence over time to antiretroviral therapy amongst HIV positive adults in South Africa: a longitudinal study. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15: 1465-1474.

Mathews WC, Mar-Tang M, Ballard C, Colwell B, Abulhosn K, Noonan C, Barber RE, Wall TL: Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of early adherence after starting or changing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002, 16: 157-172.

McAllister J, Beadsworth G, Lavie E, MacRae K, Carr A: Financial stress is associated with reduced treatment adherence in HIV-infected adults in a resource-rich setting. HIV Med. 2013, 14: 120-124.

Mellins CA, Kang E, Leu CS, Havens JF, Chesney MA: Longitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003, 17: 407-416.

Molassiotis A, Nahas-Lopez V, Chung WYR, Lam SWC, Li CKP, Lau TFJ: Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral medication in HIV-infected patients. Int J STD & AIDS. 2002, 13: 301-310.

Moralejo L, Inés S, Marcos M, Fuertes A, Luna G: Factors influencing adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Spain. Curr HIV Res. 2006, 4: 221-227.

Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, Whetten K, Leserman J, Thielman NM, Pence BW: Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2009, 71: 920-926.

Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D, Steers WN: Predictors of antiretroviral adherence. AIDS Care. 2004, 16: 471-484.

Murri R, Ammassari A, De Luca A, Cingolani A, Marconi P, Wu AW, Antinori A: Self-reported nonadherence with antiretroviral drugs predicts persistent condition. HIV Clin Trials. 2001, 2: 323-329.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Mutamba B, Othengo M, Musisi S: Psychological distress and adherence to highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in Uganda: a pilot study. Afr Health Sci. 2009, 9: 2-7.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Mojtabai R, Alexandre PK, Musisi S, Katabira E, Nachega JB, Treisman G, Bass JK: Lifetime depressive disorders and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in HIV-infected Ugandan adults: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2013, 145: 221-226.

Negash T, Ehlers V: Personal factors influencing patients’ adherence to ART in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013, 24: 530-538.

Nel A, Kagee A: The relationship between depression, anxiety and medication adherence among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013, 25: 948-955.

Nelsen A, Gupta S, Trautner BW, Petersen NJ, Garza A, Giordano TP, Naik AD, Rodriguez-Barradas MC: Intention to adhere to HIV treatment: a patient-centred predictor of antiretroviral adherence. HIV Med. 2013, 14: 472-480.

Nelson RE, Nebeker JR, Hayden C, Reimer L, Kone K, LaFleur J: Comparing adherence to two different HIV antiretroviral regimens: an instrumental variable analysis. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17: 160-167.

Nieuwkerk P, Gisolf E, Sprangers M, Danner S: Adherence over 48 weeks in an antiretroviral clinical trial: variable within patients, affected by toxicities and independently predictive of virological response. Antivir Ther. 2001, 6: 97-103.

Nilsson Schönnesson L, Diamond PM, Ross MW, Williams M, Bratt G: Baseline predictors of three types of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence: a 2-year follow-up. AIDS Care. 2006, 18: 246-253.

Nozaki I, Dube C, Kakimoto K, Yamada N, Simpungwe JB: Social factors affecting ART adherence in rural settings in Zambia. AIDS Care. 2011, 23: 831-838.

O’Connor JL, Gardner EM, Mannheimer SB, Lifson AR, Esser S, Telzak EE, Phillips AN: Factors associated with adherence amongst 5295 people receiving antiretroviral therapy as part of an international trial. J Infect Dis. 2013, 208: 40-49.

Oku AO, Owoaje ET, Oku OO, Monjok E: Prevalence and determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy amongst people living with HIV/AIDS in a rural setting in south-south Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014, 18: 133-143.

Orrell C, Bangsberg DR, Badri M, Wood R: Adherence is not a barrier to successful antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2003, 17: 1369-1375.

Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Ragland K, Laeyendecker O, Mugerwa R, Kityo C, Mugyenyi P, Quinn TC, Bangsberg DR: Treatment interruptions predict resistance in HIV-positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS. 2007, 21: 965-971.

Parutti G, Manzoli L, Marani Toro P, D'Amico G, Rotolo S, Graziani V, Schioppa F, Consorte A, Alterio L, Toro GM, Boyle BA: Long-term adherence to first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy in a hospital-based cohort: predictors and impact on virologic response and relapse. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006, 20: 48-57.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, Wagener MM, Singh N: Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with hiv infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 133: 21-30.

Pefure-Yone EW, Soh E, Kengne AP, Balkissou AD, Kuaban C: Non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Yaounde: prevalence, determinants and the concordance of two screening criteria. J Infect Public Health. 2013, 6: 307-315.

Peltzer K, Friend-du Preez N, Ramlagan S, Anderson J: Antiretroviral treatment adherence among hiv patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Pub Health. 2010, 10: 111.

Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Pierret J, Lert F, Obadia Y: Management of HIV-related stigma and adherence to HAART: evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA 2003). AIDS Care. 2006, 18: 254-261.

Pinheiro CAT, de-Carvalho-Leite JC, Drachler ML, Silveira VL: Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV/AIDS patients: a cross-sectional study in Southern Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002, 35: 1173-1181.

Plankey P, Bacchetti P, Jin C, Grimes B, Hyman C, Cohen M, Howard AA, Tien PC: Self-perception of body fat changes and HAART adherence in the women’s interagency HIV study. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13: 53-59.

Poquette AJ, Moore DJ, Gouaux B, Morgan EE, Grant I, Woods SP: Prospective memory and antiretroviral medication non-adherence in HIV: an analysis of ongoing task delay length using the memory for intentions screening test. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013, 19: 155-161.

Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, Spiegel D: Social support, substance use, and denial in relationship to antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003, 17: 245-252.

Pratt RJ, Robinson N, Loveday HP, Pellowe CM, Franks PJ, Hankins M, Loveday C: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: appropriate use of self-reporting in clinical practice. HIV Clin Trials. 2001, 2: 146-159.

Protopopescu C, Raffi F, Roux P, Reynes J, Dellamonica P, Spire B, Leport C, Carrieri MP: Factors associated with non-adherence to long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy: a 10 year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009, 64: 599-606.

Raboud J, Li M, Walmsley S, Cooper C, Blitz S, Bayoumi AM, Rourke S, Rueda S, Rachlis A: Once daily dosing improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15: 1397-1409.

Ramadhani HO, Thielman NM, Landman KZ, Ndosi EM, Gao F, Kirchherr JL, Shah R, Shao HJ, Morpeth SC, McNeill JD, Shao JF, Bartlett JA, Crump JA: Predictors of incomplete adherence, virologic failure, and antiviral drug resistance among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 45: 1492-1498.

Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Simoni JM, Kitahata MM, Crane HM: A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16: 711-716.

Remien RH, Bastos FI, Terto Jnr V, Raxach JC, Pinto RM, Parker RG, Berkman A, Hacker MA: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a context of universal access, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS Care. 2007, 19: 740-748.

Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, Vella S, Robbins GK: Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004, 8: 141-150.

Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Skripkaukas S, Bennett CL, Wolf MS: Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006, 20: 359-368.

Rodrigues R, Shet A, Antony J, Sidney K, Arumugam K, Krishnamurthy S, D'Souza G, DeCosta A: Supporting adherence to antiretroviral therapy with mobile phone reminders: results from a cohort in South India. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e40723.

Rougemont M, Stoll BE, Elia N, Ngang P: Antiretroviral treatment adherence and its determinants in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective study at Yaounde central hospital, Cameroon. AIDS Res Ther. 2009, 6: 21.

Safren SA, Kumarasamy N, James R, Raminani S, Solomon S, Mayer KH: ART adherence, demographic variables and CD4 outcome among HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2005, 17: 853-862.

Sasaki Y, Kakimoto K, Dube C, Sikazwe I, Moyo C, Syakantu G, Komada K, Miyano S, Ishikawa N, Kita K, Kai I: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) during the early months of treatment in rural Zambia: influence of demographic characteristics and social surroundings of patients. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012, 11: 34.

Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE: The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009, 24: 1101-1108.

Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB: Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004, 19: 1096-1103.

Seguy N, Diaz T, Pereira Campos D, Veloso VG, Grinsztejin B, Teixeira L, Pillotto JH: Evaluation of the consistency of refills for antiretroviral medications in two hospitals in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS Care. 2007, 19: 617-625.

Sellier P, Clevenbergh P, Ljubicic L, Simoneau G, Evans J, Delcey V, Diemer M, Bendenoun M, Mouly S, Bergmann JF: Comparative evaluation of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-saharan African native HIV-infected patients in France and Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 43: 654-657.

Van Servellen G, Chang B, Garcia L, Lombardi E: Individual and system level factors associated with treatment nonadherence in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men and women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002, 16: 269-281.

Shah B, Walshe L, Saple DG, Mehta SH, Ramnani JP, Kharkar RD, Bollinger RC, Gupta A: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and virologic suppression among HIV-infected persons receiving care in private clinics in Mumbai, India. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 44: 1235-1244.

Sherr L, Lampe F, Norwood S, Leake Date H, Harding R, Johnson M, Edwards S, Fisher M, Arthur G, Zetler S, Anderson J: Adherence to antiretroviral treatment in patients with HIV in the UK: a study of complexity. AIDS care. 2008, 20: 442-448.

Sherr L, Lampe FC, Clucas C, Johnson M, Fisher M, Leake Date H, Anderson J, Edwards S, Smith CJ, Hill T, Harding R: Self-reported non-adherence to ART and virological outcome in a multiclinic UK study. AIDS Care. 2010, 22: 939-945.

Shuter J, Bernstein SL: Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008, 10: 731-736.

Simoni JM, Frick PA, Lockhart D, Liebovitz D: Mediators of social support and antiretroviral adherence among an indigent population in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002, 16: 431-439.

Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, Shen J, Goggin K, Reynolds NR, Remien RH, Rosen MI, Bangsberg DR, Liu H: Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012, 60: 466-472.

Singh N, Berman SM, Swindells S, Justis JC, Mohr JA, Squier C, Wagener MM: Adherence of human immunodeficiency virus+infected patients to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999, 29: 824-830.

Sodergard B, Halvarsson M, Tully P, Mindouri S, Nordström ML, Lindbäck S, Sönnerborg A, Lindblad AK: Adherence to treatment in Swedish HIV-infected patients. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006, 31: 605-616.

Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, Leport C, Raffi F, Moatti JP: Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: from a predictive to a dynamic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 54: 1481-1496.

Stirratt MJ, Remien RH, Smith A, Copeland OQ, Dolezal C, Krieger D: The role of HIV serostatus disclosure in antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10: 483-493.

Sullivan PS, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV, Begley EB, Schulden J, Nakashima AK: Patient and regimen characteristics associated with self-reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2: e552.

Sumari-de Boer IM, Sprangers MAG, Prins JM, Nieuwkerk PT: HIV stigma and depressive symptoms are related to adherence and virological response to antiretroviral treatment among immigrant and indigenous HIV infected patients. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16: 1681-1689.

Tadios Y, Davey G: Antiretroviral treatment adherence and its correlates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006, 44: 237-244.

Tedaldi EM, van den Berg-Wolf M, Richardson J, Patel P, Durham M, Hammer J, Henry K, Metzler S, Önen N, Conley L, Wood K, Brooks JT, Buchacz K: Sadness in the SUN: using computerized screening to analyze correlates of depression and adherence in HIV-infected adults in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012, 26: 718-729.

Teixera C, Dourade Mde L, Santos MP, Brites C: Impact of use of alcohol and illicit drugs by AIDS patients on adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013, 29: 799-804.

Thrasher AD, Earp JAL, Golin CE, Zimmer CR: Discrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 49: 84-93.

Tiyou A, Belachew T, Alemseged F, Biadgilign S: Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in resource limited setting of southwest Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther. 2010, 7: 39.

Tran BX, Nguyen LT, Nguyen NH, Hoang QV, Hwang J: Determinants of antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV/AIDS patients: a multisite study. Glob Health Action. 2013, 6: 19570-doi:10.3402/gha.v6i0.19570

Trotta MP, Ammassari A, Cozzi-Lepri A, Zaccarelli M, Castelli F, Narciso P, Melzi S, De Luca A, Monforte AD, Antinori A: Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy is better in patients receiving non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-containing regimens than in those receiving protease inhibitor-containing regimens. AIDS. 2003, 17: 1099-1102.

Ubbiali A, Donati D, Chiorri C, Bregani V, Cattaneo E, Maffei C, Visintini R: Prediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: can patients’ gender play some role? An Italian pilot study. AIDS Care. 2008, 20: 571-575.

Ukwe CV, Ekwunife OI, Udeogaranya OP, Iwuamadi UI: Self-reported adherence to HAART in south-eastern Nigeria is related to patients’ use of pill box. Sahara J. 2010, 7: 10-15.

Unge C, Sodergard B, Marrone G, Thorson A, Lukhwaro A, Carter J, Ilako F, Ekström AM: Long-term adherence to antiretroviral treatment and program drop-out in a high-risk urban setting in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e13613.

Uusküla A, Laisaar KT, Raag M, Šmidt J, Semjonova S, Kogan J, Amico KR, Sharma A, Dehovitz J: Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and correlates to nonadherence among people on ART in Estonia. AIDS Care. 2012, 24: 1470-1479.

Venkatesh KK, Srikrishnan AK, Mayer KH, Kumarasamy N, Raminani S, Thamburaj E, Prasad L, Triche EW, Solomon S, Safren SA: Predictors of nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected south Indians in clinical care: implications for developing adherence interventions in resource-limited settings. AIDS Patient Care STD. 2010, 24: 795-802.

Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Tavakoli A, Phillips KD, Murdaugh C, Jackson K, Meding G: Social support, coping, and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with depression living in rural areas of the southeastern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007, 21: 667-680.

Wagner GJ: Predictors of antiretroviral adherence as measured by self-report, electronic monitoring, and medication diaries. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002, 16: 599-608.

Wagner GJ, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, Banks D, Klein DJ: Discrimination as a key mediator of the relationship between posttraumatic stress and HIV treatment adherence among African American men. J Behav Med. 2012, 35: 8-18.

Waite KR, Paasche-Orlow M, Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Wolf MS: Literacy, social stigma, and HIV medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2008, 23: 1367-1372.

Wanchu A, Kaur R, Bambery P, Singh S: Adherence to generic reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral medication at a tertiary center in north India. AIDS Behav. 2007, 11: 99-102.

Wang X, Wu Z: Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV/AIDS patients in rural China. AIDS. 2007, 21: S149-S155.

Wasti SP, Simkhada P, Randall J, Freeman JV, van Teijlingen E: Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Nepal: a mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7: e35547.

Watt MH, Maman S, Golin CE, Earp JA, Eng E, Bangdiwala SI, Jacobson M: Factors associated with self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a Tanzanian setting. AIDS Care. 2010, 22: 381-389.

Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Duran RE, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Penedo FJ, Schneiderman N: A stress and coping model of medication adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Health Psychol. 2005, 24: 385-392.

Webb MS, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC: Medication adherence in HIV-infected smokers: the mediating role of depressive symptoms. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009, 21: 94-105.

Weidle PJ, Wamai N, Solberg P, Liechty C, Sendagala S, Were W, Mermin J, Buchacz K, Behumbiize P, Ransom RL, Bunnell R: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care programme in rural Uganda. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1587-1594.

Woods SP, Dawson MS, Weber E, Gibson S, Grant I, Atkinson JH: Timing is everything: antiretroviral nonadherence is associated with impairment in time-based prospective memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009, 15: 42-52.

Woodward EN, Pantalone DW: The role of social support and negative affect in medication adherence for HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012, 23: 388-396.

Yun LWH, Maravi M, Kobayashi JS, Barton PL, Davidson AJ: Antidepressant treatment improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy among depressed HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 38: 432-438.

Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V: Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e80633.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC: Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013, 16: 18640.

Easthall C, Song F, Bhattacharya D: A meta-analysis of cognitive-based behaviour change techniques as interventions to improve medication adherence.BMJ Open 2013, 3..

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, Beach MC: Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013, 63: 362-366.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000, 283: 2008-2012.

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, Cooper C, Thabane L, Wilson K, Guyatt GH, Bangsberg DR: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Sahara Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006, 296: 679-690.

Shi L, Liu J, Fonseca V, Walker P, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M: Concordance of adherence measurement using self-reported adherence questionnaires and medication monitoring devices. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010, 8: 99.

Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, Shen J, Simoni JM, Reynolds NR, Goggin K, Gross R, Arnsten JH, Remien RH, Erlen JA, Liu H: Heterogeneity among studies in rates of decline of antiretroviral therapy adherence over time: results from the multisite adherence collaboration on HIV 14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013, 64: 448-454.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

12916_2014_142_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Scoring of studies according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria.(PDF 270 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Langebeek, N., Gisolf, E.H., Reiss, P. et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 12, 142 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1