Summary

Infection prevention protocols are the accepted standard to control nosocomial infections. These protective measures intensified after the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to reduce the risk of viral transmission. It is the rationale that this practice reduces nosocomial infections. We evaluated the impact of these protective measures on nosocomial infections in our center with more than 20,000 records of annual patient admission. In a retrospective study, we evaluated the incidence of nosocomial infections in Sina hospital for 9 months (April–December 2020) during the COVID-19 period and compared it with the 8 months in the pre-COVID period (April–November 2019). Despite decreasing the number of admissions during the COVID era (hospitalizations showed a reduction of 43.79%), the total hospital nosocomial infections remained unchanged; 4.73% in the pre-COVID period versus 4.78% during the COVID period. During the COVID period the infection percentages increased in the cardiovascular care unit (p-value = 0.002) and intensive care units (p-value = 0.045), and declined in cardiology (p-value = 0.046) and neurology (p-value = 0.019) wards. This study showed that intensifying the infection prevention protocols is important in decreasing the nosocomial infections in some wards (cardiology and neurology). Still, we saw increased nosocomial infection in some wards, e.g., the intensive care unit (ICU) and coronary care unit (CCU). Thus, enhanced infection prevention protocols implemented in hospitals to prevent the spread of a pandemic infection may not always decrease rates of other hospital-acquired infections during a pandemic. Due to limited resources, transfer of staff, and staff shortage due to quarantine measures may prohibit improved prevention procedures from effectively controlling nosocomial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in early 2020, many protective measurements such as hand hygiene and Personnel Protective Equipment (PPE) have been employed to reduce the risk of infection transmission [1,2,3]. The rationale is that these protocols reduce other microbial spreads in many medical and surgical wards. World Health Organization (WHO) definition of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) is an infection acquired in the hospital by a patient admitted for a reason other than that infection. The different widely used definition presented by Benenson is “An infection occurring in a patient in a hospital or other health care facility in whom the infection was not present or incubating at the time of admission. These include infections acquired in the hospital but appearing after discharge, and occupational infections among the facility staff” [4,5,6].

They comprised ventilator-associated infections or events (VAE), pneumonia (PNEU), surgical site infection (SSI), bloodstream infection (BSI), and urinary tract infection (UTI). They have a significant economic burden on the health system, and any efforts to reduce them are appreciated [7,8,9,10,11]. The impact of protective measures in the COVID era on the prevalence of nosocomial infections is contradictory. Some studies reported decreasing the nosocomial infection in specific wards such as the neurologic ward, and others reported otherwise [12, 13]. Concerning these reports, we evaluated the role of protective measures on the incidence of nosocomial infection in our hospital during 9 months in the COVID period with 8 months in the pre-COVID era.

Methods

This retrospective study utilized the hospital records of the patients hospitalized in the Sina University Hospital, Tehran, documented in April–November 2019 and April–December 2020 after approval by the Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR. TUMS. SINA HOSPITAL.REC.1400.037). Our hospital is a large well-known referral hospital with more than 20 wards (e.g., vascular surgery, trauma, general surgery, neurosurgery, oncology, medical wards, two ICUs, one CCU, two urology wards, and one transplant ward). We documented more than 20,000 records of annual patient admissions. We gathered data with the active participation of our hospital infection control committee. The infection control committee consists of specialized nurses who check daily reports of routine cultures in the ward and follow lab data of any patient suspected of the different types of infections (urinary tract, surgical site, bloodstream) and recorded in the hospital infection registry system. The total cases of hospitalization and nosocomial infections were analyzed in two periods. Also, we analyzed different types of infections according to the source of infections in 2018, 2019, and the COVID era in 2020. The findings are presented as numbers and percentages and compared between two time periods using the proportion test. The categorical variables were compared between the periods using the Χ2 test. The analyses were performed using the statistical software Stata (ver. 13). The significance level was chosen as 0.05.

Results

The total number of hospitalizations in the 8 months before COVID (April–November 2019) was 16,687; among them, 790 infections were recorded (4.73%). Moreover, in the 9 months during COVID (April–December 2020), 10,553 hospitalizations and 504 infections were recorded (4.78%). The hospitalizations showed a total reduction of 43.79% (Fig. 1). We categorized surgical, medical, and intensive care cases for easy comparison; Cardiology, Surgery, and Jaw and Face, were in one category, the three ICUs were combined, the Internal and Neurology wards, Multiple Sclerosis and Psychiatry formed one group, and finally, Orthopedics were combined. The five wards, including CCU, Kidney transplant, Oncology, Urology, the Very Important Person (VIP)–International Patient Department (IPD), remained as before. Fig. 1 presents the reduction of hospitalizations. The number of hospitalizations declined in all wards, except for the Oncology ward, which showed an increase of 12.0%. The most reduction in the hospitalization was in the VIP and transplant ward (73.59 and 55.5%, respectively; Table 1).

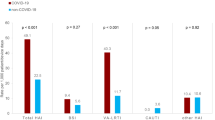

The infection percentages are presented in Table 2, divided into the hospital’s 20 wards and comparing the two time periods. The infection percentages were compared using the proportion test, leading to the p-values reported in Fig. 2. The upper and lower panels depict the wards witnessing a decrease and increase in the infection percentages, respectively. The before/during percentages were compared using the proportion test, demonstrating significant increases in CCU, ICU general, and ICU urgency wards and declines in Cardiology and Neurology (both men and women) wards.

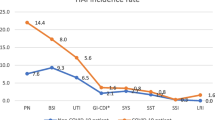

We also evaluated the total rate of nosocomial infection in 2018 separately. We compared it with the two mentioned periods in our study to ensure the complete performance of hospitals’ infection prevention control (IPC) policy one year before commencing COVID compared to 2018. The distribution is significantly different between the three years and every two subsequent years, as the Χ2 test shows (p-values < 0.001). The rate of pneumonia, UTI, and SSI decreased in COVID time compared with the same period in the pre-COVID era in 2019 (Table 3).

Finally, the microbial species distribution over the study periods is described in Table 4. We assessed a total of 4200 specimens during these periods. Some microbial species like Acinetobacter and Klebsiella increased during the COVID period compared to the pre-COVID period.

Discussion

Nosocomial infections are a global problem. Many centers’ have strategies, such as hygienic protocols, health providers’ educational programs, and stewardship programs for preventing unnecessary antibiotics administration [14]. Hospital-associated infections (HAIs) have a tremendous economic burden on the health system [7, 15]. The main reason for nosocomial infections is improper antibiotic administration [16, 17]. Recent studies propose that hygienic protocols like frequent hand washing, personal protective equipment (PPE), and mask-wearing may reduce HAIs. In a survey by Irelli et al. they compared 216 patients who were admitted to the neurology ward in 2019 (pre-COVID era) with 103 patients in 2020 (COVID era) with regard to the incidence of hospital-associated infections (HAIs); their reports revealed a lower incidence of HAIs in 2020 compared the 2019 period (23.3% versus 31.5%; p-value = 0.01) [18]. In a contradictory study by Martinez et al., they evaluated the incidence of nosocomial endocarditis in the first 2 months after the start of the COVID-2019 pandemic and compared the incidence with the same period before the pandemic; they reported increases in the incidence of infective endocarditis as HAIs in the COVID era [13, 19]. In an exciting study by Alonso et al., they evaluated the incidence of clostridioides difficile infection in a 2-month period in 2020 with the same period in the pre-COVID era (2019); despite no reduction in the antibiotics prescription during COVID era incidence of HAIs clostridioides difficile infection decreased about 70%, which underscores the importance of hygienic protocols to reduce nosocomial infections [10, 20, 21].

Losurdo et al., in a cohort observational study, compared two sets of patients in the pre-COVID (418 patients) and the COVID era (123 patients) and reported a reduction of total, superficial and deep surgical site infections in the COVID era. They emphasize this concept that hygienic protocols like mask-wearing and restriction of visitors could reduce nosocomial infections. [22]. In the supporting recommendation for reinforcing the hygienic measures, Irelli et al. emphasize the adherence to hygienic protocols for preventing nosocomial infections even after ending this pandemic [23].

In a study by Bentivegna et al., they compared the incidence of multidrug resistance (MDR) organisms in the pre-COVID era and COVID time. They revealed that hygienic protocol significantly reduced the rate of MDR infections (29% vs. 19%) [24]. Cole et al. mentioned reducing multidrug resistance organisms such as staphylococcus aureus, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus incidence with protective measures like hand washing and mask-wearing in the COVID period compared with pre-COVID period about 41%, 21%, and 80%, respectively [25]. In a study by Lo et al., a collateral benefit of the COVID-19 prevention measures on the incidence density of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) was observed where the incidence of COVID-19 was low [26].

In an exciting study, Reuben et al. evaluated the impact of preventive measures for COVID-19 on reducing Lassa fever in Nigeria and revealed the reduction of Lassa fever cases in Nigeria due to the same route of transmission [27]. Wee et al. cited the reduction of adenovirus incidence in the COVID era compared to the pre-COVID era in their referral center in Singapore (0.03% vs. 0.4%). They cited that this reduction was observed only in nosocomial infection of the adenovirus. At the same time, the rate of community-acquired adenovirus infection increased, emphasizing the effect of preventive measures in hospital reduction of nosocomial adenovirus [28]. In another study in Singapore, the rate of respiratory viral infections, MRSA, and central venous line infections decreased in the COVID era compared to the pre-COVID period due to intensifying preventive measures [29].

Wong et al. demonstrated a reduction of viral influenza A and B during the COVID era compared to the pre-COVID era in their hospital, emphasizing infection prevention and control policies (IPC) such as face masks and hand washing on the reduction of nosocomial infections again [30]. In a study by Hu et al., they emphasized the face mask besides social distancing and hand washing and mentioned that this practice could reduce HAIs [31]. Wee et al. reported their experience in the hematologic ward. They concluded that preventive measures decrease respiratory viral infection during the COVID era compared to the pre-COVID era [32]. Jabarpour et al. studied the effect of preventive infection control for COVID-19 on HAIs. They reported a significant reduction of HAIs in ICU and medical–surgical wards, different from our results [33].

Points of this study are (a) despite reducing the admissions in our center, the percentage of infection remained unchanged in the COVID period compared to the pre-COVID period (4.78% vs. 4.73%). Most studies showed a decline in nosocomial infection rates in a different ward. However, in our referral center, the quality of IPC protocols was an optimum point, so IPC measures did not reduce nosocomial infections. (b) Nosocomial infections increased in the intensive units (CCU, ICUs) and declined in the cardiology and neurology wards; the other wards remained unchanged. It seems that there are factors that affect the rate of nosocomial infections (NI), such as the shortage of nurses in ICU, lack of compliance, and exhaustion of personnel due to prolonged and demanding working hours. Thus, it is crucial to support the workforces with fresh and skilled additional staff.

This finding was different from the other study that concluded a decrease of nosocomial infection in the intensive units was probably due to more preventive measures during the COVID era. Since COVID-19 was highly prevalent in Iran during the study period, the transfer of staff to the infection wards and COVID-19 reserved ICUs led to a concomitant overload in the other wards and thereby to difficulties in adherence control measures. However, the quality of the IPC policies and implementation of the protocols in each medical center could affect the results, so we analyzed the nosocomial infection rate in three consecutive years. The changes in the NIs showed that the IPC protocols had successfully diminished the rate of nosocomial infection in 2019 comparing 2018 in our center, so it seems any study that compares these two periods should consider the quality of IPC as a confounding factor in the study.

Conclusion

The adherence to the national guidelines of infection prevention and control (IPC) should be an ongoing program despite the persistence of COVID-19. In some wards like the ICU, we should consider the lack of compliance and exhaustion of personnel due to prolonged and tedious working hours. Thus, it is crucial to support the exhausted and overworked personnel with fresh and skilled additional staff during the pandemic.

Abbreviations

- BSI:

-

Bloodstream infection

- CCU:

-

Coronary care unit

- HAIs:

-

Healthcare-associated infections

- IPC:

-

Infection prevention and control policies

- IPD:

-

International Patient Department

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistance

- PNEU:

-

Pneumonia

- PPE:

-

Personnel protective equipment

- SSI:

-

Surgical site infection

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- VAE:

-

Ventilator-associated infections or events

- VIP:

-

Very Important Person

References

Khunti K, Adisesh A, Burton C, Chan XHS, Coles B, Durand-Moreau Q, et al. The efficacy of PPE for COVID-19-type respiratory illnesses in primary and community care staff. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(697):413–6.

Liang M, Gao L, Cheng C, Zhou Q, Uy JP, Heiner K, et al. Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101751.

Cowling BJ, Zhou Y, Ip D, Leung G, Aiello AE. Face masks to prevent transmission of influenza virus: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(4):449–56.

Mayon-White R, Ducel G, Kereselidze T, Tikomirov E. An international survey of the prevalence of hospital-acquired infection. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:43–8.

Benenson AS. Control of communicable diseases manual. : The Association; 1995.

Rahimzadeh H, Tamehri Zadeh SS, Khajavi A, Saatchi M, Reis LO, Guitynavard F, et al. The tsunami of COVID-19 infection among kidney transplant recipients: a single-center study from Iran. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11(4):389–96.

Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, et al. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039–46.

Gandra S, Barter D, Laxminarayan R. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):973–80.

Stone PW. Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: an American perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconom Outcomes Res. 2009;9(5):417–22.

Mohammadi A, Aghamir SMK. The hypothesis of the COVID-19 role in acute kidney injury: a literatures review. Transl Res Urol. 2020;2(3):74–8.

Ahmadi K, Fasihi Ramandi M. Evaluation of antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of K4 synthetic peptide. Transl Res Urol. 2021;3(2):59–66.

Cerulli Irelli E, Orlando B, Cocchi E, Morano A, Fattapposta F, Di Piero V, et al. The potential impact of enhanced hygienic measures during the COVID-19 outbreak on hospital-acquired infections: A pragmatic study in neurological units. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117111.

Ramos-Martinez A, Fernández-Cruz A, Dominguez F, Forteza A, Cobo M, Sanchez-Romero I, et al. Hospital-acquired infective endocarditis during Covid-19 pandemic. Infect Prev Pract. 2020;2(3):100080.

Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Executive summary: implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):1197–202.

Mashhadi R, Khatami F, Zareian Baghdadabad L, Shabestari AN, Guitynavard F, Oliveira Reis L. A review of animal laboratory practice in the COVID-19 and safety concerns. Transl Res Urol. 2020;2(1):17–21.

Revelas A. Healthcare-associated infections: a public health problem. Niger Med J. 2012;53(2):59.

Fridkin SK, Welbel SF, Weinstein RA. Magnitude and prevention of nosocomial infections in the intensive care unit. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;11(2):479–96.

Irelli EC, Orlando B, Cocchi E, Morano A, Fattapposta F, Di Piero V, et al. The potential impact of enhanced hygienic measures during the COVID-19 outbreak on hospital-acquired infections: A pragmatic study in neurological units. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117111.

Fakhr Yasseri A, Taheri D. Urinary stone management during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Res Urol. 2020;2(1):1–3.

Ponce-Alonso M, De La Fuente JS, Rincón-Carlavilla A, Moreno-Nunez P, Martínez-García L, Escudero-Sánchez R, Pintor R, García-Fernández S, Cobo J. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on nosocomial Clostridioides difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(4):406–10.

Mohammadi Sichani M, Vakili MA, Khorrami MH, Izadpanahi M‑H, Gholipour F, Kazemi R. Predictive values of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio for systemic inflammatory response syndrome after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Transl Res Urol. 2021;3(4):154–60.

Losurdo P, Paiano L, Samardzic N, Germani P, Bernardi L, Borelli M, et al. Impact of lockdown for SARS-CoV‑2 (COVID-19) on surgical site infection rates: a monocentric observational cohort study. Updates Surg. 2020;72(4):1263–71.

Cerulli Irelli E, Morano A, Di Bonaventura C. Reduction in nosocomial infections during the COVID-19 era: a lesson to be learned. Updates Surg. 2021;73(2):785–6.

Bentivegna E, Luciani M, Arcari L, Santino I, Simmaco M, Martelletti P. Reduction of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1003.

Cole J, Barnard E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare acquired infections with multidrug resistant organisms. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(5):653–4.

Lo S‑H, Lin C‑Y, Hung C‑T, He J‑J, Lu P‑L. The impact of universal face masking and enhanced hand hygiene for COVID-19 disease prevention on the incidence of hospital-acquired infections in a Taiwanese hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:15–8.

Reuben RC, Gyar SD, Makut MD, Adoga MP. Co-epidemics: have measures against COVID-19 helped to reduce Lassa fever cases in Nigeria? New Microbes New Infect. 2021;40:100851.

Wee LE, Conceicao EP, Sim JX, Aung MK, Venkatachalam I. Impact of infection prevention precautions on adenoviral infections during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Experience of a tertiary-care hospital in Singapore. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;10:1.

Wee LE, Conceicao EP, Tan JY, Magesparan KD, Amin IB, Ismail BB, Toh HX, Jin P, Zhang J, Wee EG, Ong SJ. Unintended consequences of infection prevention and control measures during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(4):469–77.

Wong S‑C, Lam GK‑M, AuYeung CH‑Y, Chan VW‑M, Wong NL‑D, So SY‑C, et al. Absence of nosocomial influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) era: implication of universal masking in hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(2):218–21.

Hu L‑Q, Wang J, Huang A, Wang D, Wang J. COVID-19 and improved prevention of hospital-acquired infection. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(3):e318–e9.

Wee LE, Conceicao EP, Tan JY, Venkatachalam I, Ling ML. Zero healthcare-associated respiratory viral infections among haematology inpatients: Unexpected consequence of heightened infection control during COVID-19 outbreak. J Hosp Infect. 2021;107:1–4.

Du Q, Zhang D, Hu W, Li X, Xia Q, Wen T, Jia H. Nosocomial infection of COVID‑19: A new challenge for healthcare professionals. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(4):1.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Urology Research Center at Sina hospital.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Mohammadi, F. Khatami, Z. Azimbeik, A. Khajavi, M. Aloosh and S.M.K. Aghamir declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR. TUMS. SINA HOSPITAL.REC.1400.037).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, A., Khatami, F., Azimbeik, Z. et al. Hospital-acquired infections in a tertiary hospital in Iran before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wien Med Wochenschr 172, 220–226 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-022-00918-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-022-00918-1