Abstract

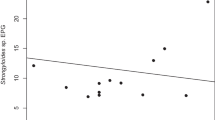

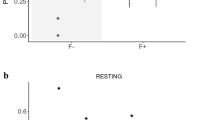

Nonhuman primates host a variety of gastrointestinal parasites that infect individuals through different transmission routes. Social contact among group members (e.g., body contact, grooming) brings the risk of parasite infection, especially when the pathogen infection is directly transmitted. Along with this, accidental provisioning (i.e., food provisioning occurring during close tourist–wildlife interactions) is also considered to increase the risk of infection, as aggregation during feeding can cause higher exposure to parasite infective stages. However, while some attention has been paid to the relationship between social behavior and parasites, the link between accidental food provisioning and characteristics of parasite infection in primates has thus far received less attention. This study examines the potential effect of accidental provisioning on patterns of inter-individual spatial association, and in turn on parasite infection risk in a wild group of black capuchin monkeys (Sapajus nigritus) in Iguazú National Park, Argentina. To do so, we simulated events of accidental provisioning via researcher-managed provisioning experiments and tested whether experimental provisioning affects the inter-individual spatial distribution within groups. In addition, we determined whether patterns of parasite infection were better predicted by naturally occurring spatial networks (i.e., spatial association during natural observations) or by provisioning spatial networks (i.e., spatial interactions during experimental provisioning). We found a significant increase in network centrality that was potentially associated with an overall increase in individual connections with other group members during experimental trials. However, when assessing the effects of natural and provisioning network metrics on parasite characteristics, we did not observe a significant effect of centrality measures (i.e., closeness and betweenness) on parasite richness and single infection by Filariopsis sp. Taken together, our findings suggest that alterations of within-group spatial networks due to accidental provisioning may have a limited influence in determining the characteristics of parasite infections in black capuchin monkeys.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agostini I, Vanderhoeven E, Di Bitetti MS, Beldomenico PM (2017) Experimental testing of reciprocal effects of nutrition and parasitism in wild black capuchin monkeys. Sci Rep 7:12778

Agostini I, Vanderhoeven E, Beldomenico PM, Pfoh R, Notarnicola J (2018) First coprological survey of helminths in a wild population of black capuchin monkeys (Sapajus nigritus) in northeastern Argentina. Mastozool Neotrop. https://doi.org/10.31687/saremmn.18.25.2.0.11

Altizer S, Hochachka WM, Dhondt AA (2004) Seasonal dynamics of mycoplasmal conjunctivitis in eastern North American house finches. J Anim Ecol 73:309–322

Altizer S, Bartel R, Han BA (2011) Animal migration and infectious disease risk. Science 331:296–302

Anderson RM, May RM (1979) Population biology of infectious diseases: part I. Nature 280:361–367

Becker DJ, Streicker DG, Altizer S (2015) Linking anthropogenic resources to wildlife-pathogen dynamics: a review and meta-analysis. Ecol Lett 18:483–495

Becker DJ, Streicker DG, Altizer S (2018) Using host species traits to understand the consequences of resource provisioning for host–parasite interactions. J Anim Ecol 87:511–525

Berman CM, Li J, Ogawa H et al (2007) Primate tourism, range restriction, and infant risk among Macaca thibetana at Mt. Huangshan, China. Int J Primatol 28:1123–1141

Boissy A (1995) Fear and fearfulness in animals. Q Rev Biol 70:165–191

Caillaud D, Levréro F, Cristescu R et al (2006) Gorilla susceptibility to Ebola virus: the cost of sociality. Curr Biol 16:R489–R491

Carne C, Semple S, MacLarnon A et al (2017) Implications of tourist–macaque interactions for disease transmission. EcoHealth 14:704–717

Chapman CA, Friant S, Godfrey K et al (2016) Social behaviours and networks of vervet monkeys are influenced by gastrointestinal parasites. PLoS ONE 11:e0161113

Cox DD, Todd AC (1962) Survey of gastrointestinal parasitism in Wisconsin dairy cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc 141:706–709

Crespo JA (1982) Ecología de la comunidad de mamíferos del Parque Nacional Iguazú, Misiones. Rev Mus Argent Cienc Nat Ecol 3:1–172

Croft DP, Madden JR, Franks DW, James R (2011) Hypothesis testing in animal social networks. Trends Ecol Evol 26:502–507

Csardi G, Nepsz T (2006) The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal 1695:1–9

de la Torre S, Snowdon CT, Bejarano M (2000) Effects of human activities on wild pygmy marmosets in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Biol Conserv 94:153–163

De Vries H, Netto WJ, Hanegraaf PLH (1993) Matman: a program for the analysis of sociometric matrices and behavioural transition matrices. Behaviour 125:157–175

Dhondt AA, Altizer S, Cooch EG et al (2005) Dynamics of a novel pathogen in an avian host: mycoplasmal conjunctivitis in house finches. Acta Trop 94:77–93

Di Bitetti MS (1997) Evidence for an important social role of allogrooming in a platyrrhine primate. Anim Behav 54:199–211

Duboscq J, Romano V, Sueur C, MacIntosh AJ (2016) Network centrality and seasonality interact to predict lice load in a social primate. Sci Rep 6:22095

Farine DR (2013) Animal social network inference and permutations for ecologists in R using asnipe. Methods Ecol Evol 4:1187–1194

Farine DR (2017) A guide to null models for animal social network analysis. Methods Ecol Evol 8:1309–1320

Farine DR, Whitehead H (2015) Constructing, conducting and interpreting animal social network analysis. J Anim Ecol 84:1144–1163

Fragaszy DM, Visalberghi E, Fedigan LM (2004) The complete capuchin: the biology of the genus Cebus. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gillespie TR (2006) Noninvasive assessment of gastrointestinal parasite infections in free-ranging primates. Int J Primatol 27:1129

Gillespie TR, Chapman CA (2006) Prediction of parasite infection dynamics in primate metapopulations based on attributes of forest fragmentation. Conserv Biol 20:441–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00290.x

Gillespie TR, Nunn CL, Leendertz FH (2008) Integrative approaches to the study of primate infectious disease: implications for biodiversity conservation and global health. Am J Phys Anthropol 137:53–69

Godfrey SS (2013) Networks and the ecology of parasite transmission: a framework for wildlife parasitology. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 2:235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.09.001

Griffin RH, Nunn CL (2012) Community structure and the spread of infectious disease in primate social networks. Evol Ecol 26:779–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9526-2

Hernandez AD, Sukhdeo MV (1995) Host grooming and the transmission strategy of Heligmosomoides polygyrus. J Parasitol 1:865–869

Janson CH (1998) Experimental evidence for spatial memory in foraging wild capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella. Anim Behav 55:1229–1243

Janson CH, Baldovino MC, Di Bitetti MS (2012) The group life cycle and demography of brown capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella nigritus) in Iguazú National Park, Argentina. In: Kappeler PM, Watts DP (eds) Long-term field studies of primates. Springer, Berlin, pp 185–212

Kean D, Tiddi B, Fahy M, Heistermann M, Schino G, Wheeler BC (2017) Feeling anxious? The mechanisms of vocal deception in tufted capuchin monkeys. Anim Behav 130:37–46

Lawson B, Robinson RA, Colvile KM et al (2012) The emergence and spread of finch trichomonosis in the British Isles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:2852–2863

MacIntosh AJ, Jacobs A, Garcia C et al (2012) Monkeys in the middle: parasite transmission through the social network of a wild primate. PLoS ONE 7:e51144

Maréchal L, Semple S, Majolo B, MacLarnon A (2016) Assessing the effects of tourist provisioning on the health of wild Barbary macaques in Morocco. PLoS ONE 11:e0155920

Martin P, Bateson P (2007) Measuring behaviour: an introductory guide, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Nunn C, Altizer SM (2006) Infectious diseases in primates: behavior. Ecology and evolution. OUP, Oxford

Nunn CL, Heymann EW (2005) Malaria infection and host behavior: a comparative study of neotropical primates. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 59:30–37

Nunn CL, Thrall PH, Leendertz FH, Boesch C (2011) The spread of fecally transmitted parasites in socially-structured populations. PLoS ONE 6:e21677

Parr NA, Fedigan LM, Kutz SJ (2013) Predictors of parasitism in wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Int J Primatol 34:1137–1152

Rego AA, Schaeffer G (1988) Filariopsis barretoi (travassos, 1921) (Nematoda: metastrongyloidea) lung parasite of primates from South America - taxonomy, synonyms and pathology. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 83:183–188

Rimbach R, Bisanzio D, Galvis N et al (2015) Brown spider monkeys (Ateles hybridus): a model for differentiating the role of social networks and physical contact on parasite transmission dynamics. Phil Trans R Soc B 370:20140110

Santa Cruz A, Borda J, Gómez L, de Rott M (2000) Endoparasitosis in captive Cebus apella. Lab Primate Newslett 39:10–13

Wheeler BC, Tiddi B, Heistermann M (2014) Competition-induced stress does not explain deceptive alarm calling in tufted capuchin monkeys. Anim Behav 93:49–58

Acknowledgements

We thank Cedric Sueur, Ivan Puga, and Sebastian Sosa for their invitation to participate in this special issue. We particularly thank Ivan Puga for statistical advice. We thank the Delegación Tecnica of the Argentine Administration of National Parks, the Centro de Investigaciones Ecologicas Subtropicales for research permission and logistical support (permit numbers: NEA 158 bis Rnv 5). We thank Ezequiel Vanderhoeven and Juliana Notarnicola at the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Tropical (INMeT) for help with running parasite analyses. We thank also Charles H. Janson, who initiated the long-term project on black capuchins in Iguazú National Park. Julie Duboscq and an anonymous reviewer provided constructive comments on the manuscript. Fieldwork was carried out with the valuable assistance of many, especially Ester Bernaldo de Quiros and Martin Fahy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This study was approved by the Animal Welfare Officer at the German Primate Center (DPZ) and by the Argentine Administration of National Parks (permit number: NEA 158 bis Rnv 5), and adhered to the legal requirements of Argentina. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiddi, B., Pfoh, R. & Agostini, I. The impact of food provisioning on parasite infection in wild black capuchin monkeys: a network approach. Primates 60, 297–306 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-018-00711-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-018-00711-y