Abstract

Purpose

Inguinal lymph nodes are a rare but recognised site of metastasis in rectal adenocarcinoma. No guideline or consensus exists for the management of such cases. This review aims to provide a contemporary and comprehensive analysis of the published literature to aid clinical decision-making.

Methods

Systematic searches were performed using the PubMed, Embase, MEDLINE and Scopus and Cochrane CENTRAL Library databases from inception till December 2022. All studies reporting on the presentation, prognosis or management of patients with inguinal lymph node metastases (ILNM) were included. Pooled proportion meta-analyses were completed when possible and descriptive synthesis was utilised for the remaining outcomes. The Joanna Briggs Institute tool for case series was used to assess the risk of bias.

Results

Nineteen studies were eligible for inclusion, encompassing 18 case series and one population-based study using national registry data. A total of 487 patients were included in the primary studies. The prevalence of ILNM in rectal cancer is 0.36%. ILNM are associated with very low rectal tumours with a mean distance from the anal verge of 1.1 cm (95% CI 0.92–1.27). Invasion of the dentate line was found in 76% of cases (95% CI 59–93). In patients with isolated inguinal lymph node metastases, modern chemoradiotherapy regimens in combination with surgical excision of inguinal nodes are associated with 5-year overall survival rates of 53–78%.

Conclusion

In specific subsets of patients with ILNM, curative-intent treatment regimens are feasible, with oncological outcomes akin to those demonstrated in locally advanced rectal cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal lymph nodes are a rare but recognised site of metastasis in rectal adenocarcinoma. Lymphatic drainage of the rectum is primarily via the mesorectal nodes and subsequently via the nodal chains associated with the mesenteric vessels [1]. In very low rectal cancers, however, lymphatic spread has been demonstrated via inguinal nodes in a similar fashion to that seen in anal canal squamous cell cancers [2,3,4,5]. A further explanation for inguinal lymph node metastases (ILNM) has been hypothesised, whereby locally advanced disease obstructs the proximal mesorectal lymphatic pathway leading to alternate drainage via inferior superficial routes [6]. ILNM have been reported in both locally advanced disease and relatively early cancers, seemingly supporting the existence of both pathways [7,8,9].

At present, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) considers ILNM as non-regional lymph node involvement. As such, ILNMs are deemed to represent distant metastatic or stage IV disease [10]. However, recent case series demonstrate significantly better survival outcomes for patients with ILNM treated with curative intent when compared to patients with distant solid organ metastatic disease [8, 9, 11], thereby suggesting the reduced survival outcomes associated with distant metastases should not apply to these patients.

No guidance exists for the management of ILNM in rectal adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, no accepted incidence rates or prognostic data are available beyond small case series. Therefore, there is limited evidence available to clinicians when treating patients with ILNM and treatment is primarily guided by the judgement and experience of local clinicians. This systematic review aims to collate and summarise all primary research involving ILNM from rectal adenocarcinoma to characterise patients with ILNM and ultimately provide clinicians with higher-level evidence for optimal management strategies.

Methods

This systematic review has been reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. A prospective review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (registration no. CRD42022385514).

Search strategy

A systematic search was performed using PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Library, Embase, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and Scopus databases. The following search algorithm, including exploded Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), was used: (Rectal cancer OR Rectal adenocarcinoma) AND (Inguinal lymph nodes OR inguinal lymphadenopathy OR inguinal lymph node metastases). Results were filtered to human studies published in the English language. The final searches took place in December 2022.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

All randomised and non-randomised studies which report original data on the presentation, management or prognosis of patients with inguinal lymph node metastases associated with rectal adenocarcinomas were included.

Exclusion

Studies reporting on patients with anal squamous cell cancers were excluded from this review. All studies published in languages other than English were excluded, and studies available as conference abstracts only or those not published in peer-reviewed journals were excluded. Case reports were also excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors independently screened each article identified by the initial search using the study title and abstract in reference to the eligibility criteria within the Rayyan software [13]. Conflicts were resolved via discussion. Screened articles were then included in a full-text review to confirm final eligibility. The database search was supplemented with forward and backward chaining of included study’s references and citations, in addition to utilising the “similar articles” feature within the PubMed database.

The primary outcome was treatment modality and subsequent survival. Secondary outcomes included prevalence, presentation and complications from treatment.

Data was manually and independently extracted onto a prospectively designed database. All case series underwent quality analysis using the critical appraisal tool developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute [14]. This tool is specific to case series and is designed to analyse the risk of selection, reporting and measurement bias.

Statistical analysis

Pooled proportions were calculated using the pooled number of events and cases where possible. When summary statistics were reported in isolation, meta-analyses of means were calculated using a random-effects model and the metan command in Stata v14 (Stata Corp). Meta-analyses of means are presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Survival rates were extracted from text or Kaplan–Meier curves [15]. When summary statistics were reported as a median, and a range or interquartile range (IQR), mean and standard deviation (SD) estimation was utilised [16, 17].

Results

Study selection

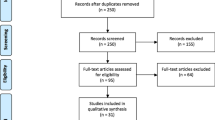

The PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1) summarises the study selection process. The initial search yielded 620 references, from which 157 duplicates were removed. The remaining 463 records were screened down to 43 studies which underwent full-text review. Eleven studies reported in languages other than English [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], five case reports [29,30,31,32,33], seven irrelevant studies [4, 34,35,36,37,38,39] and three reports which were abstracts only [40,41,42] were excluded. Two further studies for inclusion were identified through forward chaining of citations. In total, 19 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review [2, 8, 9, 11, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Study characteristics

The included studies comprise 18 case series: two are multicentre, and the remaining 16 are single-centre. One study is population-based and uses national registry data. In total, 487 patients with inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma are included. Time periods of patient recruitment in the included studies range widely, the earliest starting in 1949 and the latest included patients treated up to 2020. Table 1 summarises the study characteristics.

Bias and quality analysis

Results of the bias and quality analysis are displayed in Table 2. Several studies demonstrated similar drawbacks, such as incomplete reporting of long-term outcomes and patient demographics. However, most studies scored highly for quality and presented sufficient data to limit bias.

Patient and primary tumour characteristics

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the included patients and primary rectal tumours. Rectal tumours tended to be very low, with a pooled mean distance from the anal verge of 1.1 cm, despite 20.8% of tumours being located more than 5 cm from the anal verge. Malignant invasion of the dentate line was common (76%), and tumours were more likely to be locally advanced (81.6% T3–T4 disease). However, involved mesorectal lymph nodes were not universal; 32% of patients had no mesorectal nodal involvement. Within the included patients, unilateral ILNM were more prevalent than bilateral ILNM (72.1% vs 27.9%).

Presentation

Just two studies report on the incidence of ILNM in rectal adenocarcinoma [8, 46]. When pooled, 80 patients from 22,130 cases of rectal cancer demonstrated ILNM, giving a pooled incidence of 0.36%. Within the included single-centre case series, a pooled mean of 17.8 cases was identified for every 10 years of the study periods. This figure can be extrapolated to suggest that large tertiary cancer centres see, on average, 1.8 cases of ILNM from rectal adenocarcinomas each year.

The most common definition of a metachronous presentation, as defined by primary studies, was the identification of ILNM within 1 year of the primary rectal tumour. Given this definition, synchronous ILNM had equal representation to metachronous presentations in the data set (51.2% vs 48.8%, respectively).

When reported, preoperative diagnosis of ILNM was with computed tomography (CT) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). The most common definition of a clinically positive ILN was FDG-PET positivity, abnormal morphology or a short-axis diameter of 10 mm or greater [49, 52, 55]. Within the included studies, there is variable use of lymph node biopsy to histologically confirm metastases prior to ILN dissection, and no clear consensus is demonstrated [40, 44, 48, 53].

Out of 399 patients for whom it was reported, 196 (49.1%) were diagnosed with isolated ILNM metastases only, whilst 203 (51.9%) had distant solid organ metastases in addition to ILNM. Regarding synchronous ILNM only, 63.6% of patients had disease isolated to just the inguinal lymph nodes (isolated synchronous inguinal lymph node metastases, SILNM), and 36.4% had ILNM in addition to distant organ metastases (synchronous inguinal lymph node metastases and distant organ metastases, SILNM&DOM). For metachronous presentations, 24.5% were isolated (isolated metachronous inguinal lymph node metastases, MILNM), and 80.3% had distant metastases (metachronous inguinal lymph node metastases and distant organ metastases, MILNM&DOM). Given the expected differences in the treatment and prognosis of these four presentations, all outcomes were analysed in these four distinct groups.

Treatment

Chemoradiotherapy

When reported, 95.1% (174 of 183) of patients from all groups had a radical rectal resection with curative intent. Eight of the remaining nine patients belonged to the SILNM&DOM group and were treated palliatively because of the presence of distant metastatic disease on presentation. The final patient demonstrated a complete clinical response of both the primary tumour and the ILNM to chemoradiotherapy and was successfully managed with a watch-and-wait approach.

The heterogeneity of the included studies limits meaningful analysis regarding the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NACR). The time period of patient recruitment and TNM staging vary widely. Accepting these limitations, pooled rates of NACR for isolated SILNM and SILNM&DOM are 65.2% and 92%, respectively. For isolated MILNM, 50% had NACR prior to rectal resection. For MILNM&DOM cases, reporting of NACR was insufficient to calculate summary rates.

External beam radiotherapy targeted at the inguinal nodes was sporadically reported upon. Therefore, mean rates for each group are not calculable. Abd El Aziz et al. report this in the greatest detail and use a similar dose (median 50.4 Gy, range 45–66) for both inguinal and rectum-targeted radiotherapy. The mean rate of use for all patients was 45.7%, but studies were polarised and reported high (79–100%) or low usage (0–3%), suggesting significant centre-specific variation in protocols.

Surgical treatment of ILNM

Ten studies reported on the surgical excision of ILNM, including 204 patients [9, 11, 40, 43, 45, 49, 50, 53, 55, 57]. Only two studies describe the surgical technique in detail [49, 53]. Both describe excisions which included both clinically positive and negative nodes. Abd El Aziz et al. [11] report the excision of clinically positive nodes only in some cases and the complete dissection of superficial inguinal lymph nodes in others. Furthermore, the depth of dissection was limited to the superficial inguinal nodes in two studies [40, 45], but Tanabe et al. and Hasegawa et al. describe additional dissection of the deep inguinal nodes [49, 53]. Abd El Aziz et al. also describe the use of minimally invasive lymph node dissection, an approach utilising laparoscopic ports within the femoral triangle [58, 59]. The remaining studies do not detail the technique. Given the available data, comparative analysis of long-term outcomes by surgical technique is not possible.

Three studies reported on postoperative complications of groin dissection for ILNM [47, 49, 55]. Clavien–Dindo [60] (CD) grade II and III complications were developed by 20.5% (8/39) and 17.9% (7/39) of cases, respectively. No CD grade IV or higher complications were reported. Complications included lymphorrhoea, seroma, wound infection and lymphoedema.

Recurrence and survival

Heterogeneity and limited reporting in primary studies precluded comparative or proportional meta-analyses for recurrence or survival outcomes. Data synthesis is, therefore, descriptive.

Studies published before 2010 either did not report or reported poor survival outcomes for patients with any form of ILNM [2, 46, 50, 51, 54]. The largest study from this period, Graham et al. [46], considered treatment “predominantly palliative” given coexistent advanced pelvic or distant disease. Luna-Perez et al. [50] also report 0% 5-year overall survival and conclude that “only palliative treatment should be indicated”.

However, more recent studies have demonstrated improved outcomes, particularly for isolated ILNM. For isolated SILNM and MILNM, 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival reported in the largest and most recent series are 82–100%, 53–86% and 53–78%, respectively [9, 11, 47, 49, 53]. Survival is worse for patients with concurrent distant organ metastases, whether this is found synchronously or metachronously. Abd El Aziz et al. included eight patients with SILNM&DOM who underwent NACR, curative intent resection and surgical excision of affected inguinal lymph nodes and reported 47% and 21% 3-year and 5-year overall survival, respectively. Yeo et al. report on seven patients with MILNM&DOM and demonstrate 0% 3- and 5-year survival with a mean overall survival of 14 ± 6.9 months from the time of recurrence.

When focusing on isolated SILNM, Hasegawa et al. and Abd El Aziz et al. report the highest 5-year overall survival for this cohort at 77.5% and 53%, respectively. All but one patient from both groups underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 25/29 (86.2%) underwent radiotherapy. Abd El Aziz et al. report radiotherapy was targeted rectally and at the inguinal region. Hasegawa et al. do not report on the targeted site of radiotherapy, but state all included patients underwent surgical excision of ILNM in addition to curative-intent radical rectal resection. Eight of 14 (57.1%) patients in the study by Abd El Aziz et al. had limited excision of clinically positive nodes, and the remainder from both studies had more extensive ILN dissection. Nine patients in each group had adjuvant chemotherapy. Within the patients reported on by Abd El Aziz et al., six patients developed distant recurrence, and two developed inguinal region recurrence. Both inguinal recurrences were contralateral to the operated side. For Hasegawa et al., six patients developed recurrence, four within the pelvis and two at distant sites. No inguinal recurrences were reported.

For isolated MILNM, no modern studies report survival and recurrence figures specific to this cohort. Three studies [11, 40, 53] report treating such patients with chemotherapy and ILN surgical dissection. One of these studies pooled survival rates with isolated SILNM and reported a 5-year overall survival of 55.3% for 31 patients [53]. More specific oncological outcome data for this cohort is not available in the current literature.

ILNM response to chemoradiotherapy

Hasegawa et al. [49] performed PET-CT in all 15 patients in their series after NACR. All five patients without FDG uptake in ILN after NACR had no histopathological evidence of disease in the inguinal nodes retrieved during dissection. In the case of persistently FDG-avid PET-CT, just 4/9 (44.4%) were histologically positive for metastases. Within the isolated SILNM cohort, Abd El Aziz et al. reported 9/13 (69.2%) patients had histologically positive nodes after NACR.

Discussion

This review demonstrates that for specific subsets of patients with ILNM, modern chemoradiotherapy regimens in conjunction with surgical ILN dissection can achieve survival rates significantly above that expected for rectal cancers with distant solid organ metastases [61]. In fact, for those with isolated SILNM, overall survival rates equal or surpass those published in large-volume trials of patients with rectal cancer with locoregional nodal involvement [62, 63].

To achieve higher survival rates, there appears to be a role for surgical dissection of the inguinal nodes. The centres demonstrating the best long-term oncological outcomes utilise a combination of NACR and surgical ILN dissection. From the data set, it is unclear whether dissection should be limited to clinically positive nodes or more extensive nodal clearance of the inguinal region. Abd El Aziz et al. demonstrated no ipsilateral inguinal recurrence after limited dissection of just clinically positive nodes in eight patients [11]. Both techniques have therefore been utilised and demonstrated success, but recommendations are not possible with such small sample sizes.

Furthermore, the optimal depth of dissection remains uncertain. Hagemans et al. suggest limiting dissection to superficial nodes only [47], a recommendation supported by their study of 17 patients who underwent superficial ILN dissection without inguinal recurrence. Hasegawa et al., however, suggest the additional excision of deep inguinal nodes [49]. Therefore, there is no consensus, and the limited data set precludes a recommendation.

Chemoradiotherapy appears to play an essential role. In two separate series reporting radiologically positive ILNM after NACR, just 4/15 (27%) and 9/13 (69%) had confirmed metastases on pathological examination, respectively [11, 49]. The limited data shows that inguinal nodes are likely responsive to systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In Hasegawa et al.’s series, all patients without FDG uptake in ILN after chemoradiotherapy had negative histology, thereby suggesting that ILN dissection may not be necessary in such cases.

ILN dissection is associated with significant morbidity for patients. Wound complications such as infection, seroma, wound necrosis and lymphorrhoea occur in more than 50% of patients after ILN dissection for conditions such as melanoma or genital squamous cell cancers, where lymphadenectomy is performed more routinely [64, 65]. This review found wound complication rates of 38.5% specific to inguinal nodal clearance in cases of rectal adenocarcinoma. As such, ILN dissection should be employed with caution. This review finds 5-year overall survival rates of 0–21% for patients with distant solid organ metastases in addition to ILNM, not dissimilar to established survival rates for patients with stage IV disease [61, 66]. It would, therefore, appear harder to justify the morbidity of ILN dissection in such patients. However, if curative intent treatment is possible for the associated solid organ metastases, surgical excision may have a role.

ILNM are rare, as evidenced by the identification of under 500 eligible patients for this review. Almost all the primary data is found in case series of 40 patients or fewer. Selection and publication biases are, therefore, inherent risks. Additionally, reporting variability and inter-study heterogeneity are common, as demonstrated by each study’s highly variable inclusion criteria. The limitations in the primary data inevitably limit conclusions regarding the optimal treatment of ILNM. Conclusions are not, therefore, recommendations and are subject to challenge from original higher-quality evidence.

Further single-centre case series are unlikely to add significantly to the knowledge base. There is, therefore, a need for higher volume, impactful research in this field. Given the rarity of ILNM, standard study recruitment approaches would likely never reach the patient numbers sufficient for meaningful results. A multinational registry similar to the mASCARA registry for anal squamous cell cancers could provide additional data [67]. The inclusion of ILNM as a factor in existing registries for colorectal cancer should also be considered. Furthermore, expert consensus opinion would provide clinical teams treating patients with ILNM much-needed guidance. At present, however, this review represents a summation of the current understanding in this field and provides a contemporary overview for aid clinicians involved in treating patients with ILNM from rectal adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

Although rare, patients with inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma are likely to be encountered regularly in large centres. Optimal treatment strategies have not yet been established. Some centres have demonstrated successful management utilising chemoradiotherapy and surgical ILN dissection. For patients without accompanying distant solid organ metastases, such strategies demonstrate survival rates similar to patients with stage III disease. Therefore, ILNM can be considered as locoregional nodal involvement and treated accordingly.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during this review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ILNM:

-

Inguinal lymph node metastases

- MILNM:

-

Metachronous inguinal lymph node metastases

- MILNM&DOM:

-

Metachronous inguinal lymph node metastases and distant organ metastases

- NACR:

-

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

- SILNM:

-

Synchronous inguinal lymph node metastases

- SILNM&DOM:

-

Synchronous inguinal lymph node metastases and distant organ metastases

References

Kaur H, Ernst RD, Rauch GM, Harisinghani M (2019) Nodal drainage pathways in primary rectal cancer: anatomy of regional and distant nodal spread. Abdom Radiol 44(11):3527–3535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02094-0

Bebenek M, Wojnar A (2009) Infralevator lymphatic drainage of low-rectal cancers: preliminary results. Ann Surg Oncol 16(4):887–892. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0324-9

Gretschel S, Warnick P, Bembenek A et al (2008) Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Eur J Surg Oncol 34(8):890–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2007.11.013

Damin DC, Tolfo GC, Rosito MA, Spiro BL, Kliemann LM (2010) Sentinel lymph node in patients with rectal cancer invading the anal canal. Tech Coloproctol 14(2):133–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0582-3

Maeda K, Maruta M, Utsumi T, Hosoda Y, Horibe Y (2002) Does perifascial rectal excision (i.e. TME) when combined with the autonomic nerve-sparing technique interfere with operative radicality? Colorectal Dis 4(4):233–239. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00358.x

Grinnell RS (1942) The lymphatic and venous spread of carcinoma of the rectum. Ann Surg 116(2):200

Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, São Julião GP et al (2013) Clinical relevance of positron emission tomography/computed tomography-positive inguinal nodes in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Colorectal Dis 15(6):674–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12159

Saiki Y, Yamada K, Tanaka M, Fukunaga M, Irei Y, Suzuki T (2022) Prognosis of anal canal adenocarcinoma versus lower rectal adenocarcinoma in Japan: a propensity score matching study. Surg Today 52(3):420–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-021-02350-1

Sato H, Maeda K, Kinugasa Y et al (2022) Management of inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal and anal canal adenocarcinoma. Colorectal Dis 24(10):1150–1163. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16169

Edge SB (2017) AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn. Springer, New York

Abd El Aziz MA, McKenna NP, Jakub JW et al (2022) Rectal cancer with synchronous inguinal lymph node metastasis without distant metastasis. A call for further oncological evaluation. Eur J Surg Oncol 48(5):1100–1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2021.12.018

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S et al (2020) Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth 18(10):2127–2133. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR (2007) Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 8(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-8-16

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T (2018) Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res 27(6):1785–1805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216669183

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Abelevich AI, Ovchinnikov VA (2003) Novel method of lymphatic dissection in rectal cancer with metastases to the inguinal lymph nodes. Vopr Onkol 49(6):766–768

Akai M, Iwakawa K, Yasui Y et al (2018) Local recurrence of rectal cancer under perineal skin after abdominoperineal resection. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho [Jpn J Cancer Chemother] 45(13):1830–1832

Futagami F, Konishi I, Ninomiya I (1999) A case of rectal cancer with lymph node metastasis (N4) successfully treated with low-dose cisplatin and UFT. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho [Jpn J Cancer Chemother] 26(10):1491–1494

Kanoh T, Ohnishi T, Danno K et al (2010) A case of successfully treated lower rectal cancer with both inguinal lymph nodes by chemoradiotherapy. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho [Jpn J Cancer Chemother] 37(12):2611–2613

Makino S, Ide Y, Murata K (2011) Preoperative chemoradiation (XELOX/RT) therapy for anal canal adenocarcinoma with the metastasis to inguinal lymph node. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 38(12):2048–2050

Morimoto Y, Fujikawa H, Omura Y et al (2022) the watch and wait strategy for lower rectal cancer patients who achieved clinical complete response after chemotherapy to treat inguinal lymph node metastasis following total neoadjuvant therapy—a case report. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 49(3):297–299

Sato H, Masumori K, Koide Y et al (2021) Clinical study of inguinal lymph node metastasis in anal canal adenocarcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 48(13):1944–1946

Sato J, Karasawa H, Maeda S et al (2016) A successful case of conversion therapy after chemotherapy for advanced rectal cancer with inguinal lymph node metastasis. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho [Jpn J Cancer Chemother] 43(12):2145–2147

Timofeev IuM (1997) Inguinal lymphadenectomy in malignant anal tumors. Vopr Onkol 43(3):327–329

Ueta K, Yamashita K, Sumi Y et al (2016) The local control effect of surgical treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal adenocarcinoma with inguinal lymph node metastasis. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 43(12):1443–1445

Yamamoto J, Ishibe A, Suwa H et al (2017) Inguinal node dissection for lower rectal and anal canal adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg 50(2):95–103. https://doi.org/10.5833/jjgs.2015.0113

Avill R (1984) Carcinoma of the rectum and anal canal with inguinal lymph node metastases—long term survival. Br J Clin Pract 38(9):324–325

Bin Traiki T, Khalessi A, Phan-Thien KC (2019) Inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma. ANZ J Surg 89(4):431–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.14091

Ergete W, Assefa P (1999) Unusual presentation of rectal carcinoma in a young woman. Ethiop Med J 37(3):189–193

Sun Y, Lin Y, Liu Z, Jiang W, Chi P (2022) Combined laparoscopic lymphoadenectomy of lateral pelvic and inguinal nodal metastases using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging guidance in low rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 22(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02193-1

Zuhdy M, Elbalka SS, Hamdy O et al (2018) A totally laparoendoscopic approach for low rectal cancer with inguinal nodal metastasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 29(1):60–64. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2018.0442

Allouni AK, Sarkodieh J, Rockall A (2013) Nodal disease assessment in pelvic malignancy. Imaging 22(1):20120016. https://doi.org/10.1259/imaging.20120016

Branagan G (2011) Staging and management of inguinal nodes. Colorectal Dis 13(Suppl 1):29–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02496.x

Bruce MB, Teague CA, Isbister WH (1986) Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma: a clue to its pathogenesis. Aust N Z J Surg 56(5):439–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1986.tb02349.x

Cornelis F, Paty PB, Sofocleous CT, Solomon SB, Durack JC (2015) Percutaneous cryoablation for local control of metachronous inguinal lymph node metastases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 38(5):1369–1372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-0946-6

Sharapova S, Hartgill U, Torayraju P, Hanekamp BA, Folkvord S (2021) A man in his forties with anal tumour and inguinal lymphadenopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 141(8):25. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.20.0722

Zheng R, Zhang Y, Chen R et al (2022) Necessity of external iliac lymph nodes and inguinal nodes radiation in rectal cancer with anal canal involvement. BMC Cancer 22(1):657. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09724-9

Hagemans J, Rothbarth J, Verhoef C, Burger J (2019) Treatment of inguinal lymph node metastases in rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 45(2):e44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.10.182

Neto MX (1964) Inguinal node metastases in carcinoma of the recto-sigmoid. Bull Sci Issue 10:14–18

Nozawa H, Shiratori H, Kawai K et al (2019) Risk factors and therapeutic significance for inguinal lymph node metastasis in advanced lower rectal cancer. J Global Oncol 5(Supplement):120. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2019.5.suppl.120

Adachi T, Hinoi T, Egi H, Ohdan H (2013) Surgical treatment for isolated inguinal lymph node metastasis in lower rectal adenocarcinoma patients improves outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis 28(12):1675–1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1746-1

Bardia A, Greeno E, Miller R et al (2010) Is a solitary inguinal lymph node metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the rectum really a metastasis? Colorectal Dis 12(4):312–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01821.x

Chen M, Liu S, Xu M, Yi HC, Liu Y, He F (2021) Radiation boost for synchronous solitary inguinal lymph node metastasis during neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Discov Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-021-00455-0

Graham RA, Hohn DC (1990) Management of inguinal lymph node metastases from adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 33(3):212–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02134182

Hagemans JAW, Rothbarth J, van Bogerijen GHW et al (2019) Treatment of inguinal lymph node metastases in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 26(4):1134–1141. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07191-4

Hamano T, Homma Y, Otsuki Y, Shimizu S, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi Y (2010) Inguinal lymph node metastases are recognized with high frequency in rectal adenocarcinoma invading the dentate line. The histological features at the invasive front may predict inguinal lymph node metastasis. Colorectal Dis 12(10):e200–e205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02134.x

Hasegawa H, Matsuda T, Yamashita K et al (2022) Clinical outcomes of neoadjuvant therapy followed by selective inguinal lymph node dissection and total mesorectal excision for metastasized low rectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg 408(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02739-7

Luna-Perez P, Corral P, Labastida S, Rodriguez-Coria D, Delgado S (1999) Inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 70(3):177–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/%28SICI%291096-9098%28199903%2970:3%3C177::AID-JSO6%3E3.0.CO;2-0

Mesko TW, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Petrelli NJ (1994) Inguinal lymph node metastases from adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Am J Surg 168(3):285–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610%2805%2980204-1

Shiratori H, Nozawa H, Kawai K et al (2020) Risk factors and therapeutic significance of inguinal lymph node metastasis in advanced lower rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 35(4):655–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03520-2

Tanabe T, Shida D, Komukai S, Nakamura Y, Tsukamoto S, Kanemitsu Y (2019) Long-term outcomes after surgical dissection of inguinal lymph node metastasis from rectal or anal canal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 19(1):733. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5956-y

Tocchi A, Lepre L, Costa G et al (1999) Rectal cancer and inguinal metastases: prognostic role and therapeutic indications. Dis Colon Rectum 42(11):1464–1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02235048

Ueta K, Matsuda T, Yamashita K et al (2019) Treatment strategy for rectal cancer patients with inguinal lymph node metastasis. Anticancer Res 39(10):5767–5772. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.13779

Wang R, Wu P, Shi D et al (2014) Risk factors of synchronous inguinal lymph nodes metastasis for lower rectal cancer involving the anal canal. PLoS ONE 9(11):e111770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111770

Yeo SG, Lim HW, Kim DY et al (2014) Is elective inguinal radiotherapy necessary for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma invading anal canal? Radiat Oncol 9:296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-014-0296-1

Abbott AM, Grotz TE, Rueth NM, Hernandez Irizarry RC, Tuttle TM, Jakub JW (2013) Minimally invasive inguinal lymph node dissection (MILND) for melanoma: experience from two academic centers. Ann Surg Oncol 20(1):340–345. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2545-6

Jakub JW, Terando AM, Sarnaik A et al (2017) Safety and feasibility of minimally invasive inguinal lymph node dissection in patients with melanoma (SAFE-MILND): report of a prospective multi-institutional trial. Ann Surg 265(1):192–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000001670

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240(2):205–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

Office for National Statistics. Cancer survival in England—adults diagnosed. www.ons.gov.uk2019. Accessed on 16 Feb 2023

André T, Meyerhardt J, Iveson T et al (2020) Effect of duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer (IDEA collaboration): final results from a prospective, pooled analysis of six randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 21(12):1620–1629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30527-1

Deijen CL, Vasmel JE, de Lange-de Klerk ESM et al (2017) Ten-year outcomes of a randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colon cancer. Surg Endosc 31(6):2607–2615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5270-6

Faut M, Heidema RM, Hoekstra HJ et al (2017) Morbidity after inguinal lymph node dissections: it is time for a change. Ann Surg Oncol 24(2):330–339. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5461-3

Gupta MK, Patel AP, Master VA (2017) Technical considerations to minimize complications of inguinal lymph node dissection. Transl Androl Urol 6(5):820–825. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2017.06.06

Engstrand J, Nilsson H, Strömberg C, Jonas E, Freedman J (2018) Colorectal cancer liver metastases—a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer 18(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3925-x

Brogden DRL, Kontovounisios C, Pellino G, Bower M, Mills SC, Tekkis PP (2019) Improving outcomes for the treatment of anal squamous cell carcinoma and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Tech Coloproctol 23(12):1109–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-02121-8

Funding

No funding was sought or received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the production of this manuscript and accompanying documents.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wyatt, J., Powell, S.G., Ahmed, S. et al. Inguinal lymph node metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol 27, 969–978 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-023-02826-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-023-02826-x