Abstract

3,4-Methylenedioxymetamphetamine(MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy (MDMA-AP) is a proposed treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that may be approved for adults soon. PTSD is also common among trauma-exposed adolescents, and current treatments leave much room for improvement. We present a rationale for considering MDMA-AP for treating PTSD among adolescents. Evidence suggests that as an adjunct to therapy, MDMA may reduce avoidance and enable trauma processing, strengthen therapeutic alliance, enhance extinction learning and trauma-related reappraisal, and hold potential beyond PTSD symptoms. Drawing on existing trauma-focused treatments, we suggest possible adaptations to MDMA-AP for use with adolescents, focusing on (1) reinforcing motivation, (2) the development of a strong therapeutic alliance, (3) additional emotion and behavior management techniques, (4) more directive exposure-based methods during MDMA sessions, (5) more support for concomitant challenges and integrating treatment benefits, and (6) involving family in treatment. We then discuss potential risks particular to adolescents, including physical and psychological side effects, toxicity, misuse potential, and ethical issues. We argue that MDMA-AP holds potential for adolescents suffering from PTSD. Instead of off-label use or extrapolating from adult studies, clinical trials should be carried out to determine whether MDMA-AP is safe and effective for PTSD among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

3,4-Methylenedioxymetamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy (MDMA-AP) is a combination of psychopharmacology and psychological intervention used to treat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Phase 3 clinical trials of MDMA-AP for the treatment of PTSD among adults have finished, and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval looks likely in the coming year [1, 2]. The potential, limitations, risks, and best practices of this form of treatment for adults are under active discussion [3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, adolescents also suffer from high rates of PTSD and while evidence-based psychological treatments exist, there is still a large group of young patients for whom treatment is ineffective. To alleviate unnecessary suffering and prolonged symptoms, new forms of treatment are called for.

If MDMA-AP is approved as a treatment for PTSD, the question of extending it to adolescents will soon follow and it is prudent to discuss and study the potential risks and benefits of extending treatment to adolescents beforehand. Here, we present a rationale for considering MDMA-AP for adolescents, provide initial observations and ideas about what researchers and clinicians might need to pay special attention to if MDMA-AP were to be used with adolescents, and point out areas where we especially need more research and information.

We will limit our discussion to adolescents of approximately 14–17 years of age. We will further only consider MDMA-AP for PTSD specifically (for some of the related issues in possibly extending psychedelic-assisted treatment to minors, see [9, 10]).

Rationale and potential benefits

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is unfortunately not uncommon among adolescents. More than half of adolescents may face a potentially traumatic event before they turn eighteen [11, 12]. Adolescents are generally resilient in the face of trauma. Still, depending on a host of peri-traumatic and posttraumatic factors, between 5 and 25% of those exposed go on to develop long-lasting, clinically relevant symptoms of PTSD [12,13,14,15].

Several evidence-based psychological treatments for PTSD among adolescents have been developed. The best evidence exists for the efficacy of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral treatments [16,17,18], such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT [19]), Prolonged Exposure for Adolescents (PE-A [20]), Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET/KIDNET [21, 22]), and (developmentally adapted) Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT/D-CPT [23, 24]). These treatments are effective, resulting in large improvements in PTSD symptoms on average [17, 25]. However, even in carefully conducted clinical trials around 11% of minor participants drop-out during treatment [26], with adolescents even more likely to drop-out than children [27]. Avoidance, number of traumatic events experienced, and quality of adolescent-therapist relationship further appear to predict drop-out [27,28,29]. In addition, between a quarter to half of participants fail to respond adequately to treatment [27, 30,31,32]. Higher age and high levels of PTSD symptoms predict non-response [27], but more specific reasons may include inadequate emotional engagement and non-constructive forms of processing the traumatic experiences during treatment [18, 19, 33]. Much could still be achieved by making existing treatments more widely available for adolescents suffering from PTSD. However, alternative treatment options are also needed, especially for adolescents who are not able to complete current treatments, or do not benefit adequately from them.

Trials of MDMA-AP for PTSD have found the treatment effective in reducing PTSD symptoms and promoting remission in adults [2, 34]. Still, it is not yet clear how MDMA-AP would fare in a direct comparison to the trauma-focused psychological treatments treatment guidelines currently recommend for PTSD, such as PE, CPT, or NET. Meta-analyses on these trauma-focused treatments have found similar-sized effects on symptoms and remission in adults as those reported in the most recent Phase 3 trial of MDMA-AP [5], although high drop-out rates of up to 30–50% are also reported [35, 36]. Effect sizes are roughly similar for trauma-focused treatments among adolescents [16, 18], though we do not yet know how MDMA-AP for adolescents would fare. Nonetheless, there are reasons to suspect that MDMA-AP could be more effective or better tolerated as a treatment option, or be effective for a group of adolescents that now fail to respond to therapy.

First, MDMA may reduce avoidance and enable trauma processing for individuals who feel unable to revisit their traumatic memories or are too overwhelmed by negative emotions to engage with them when they try to do so. By reducing anxiety and stress reactivity [37, 38], as well as detection of and responsivity to negative emotional information [37, 39, 40], while enhancing mood and receptiveness [37, 41, 42], MDMA could both attenuate overly negative reactions to traumatic memories [43] and help people tolerate such reactions. In addition, increased overall arousal [37, 44] and comfort when discussing emotional memories [45] under MDMA may increase motivation to engage, while reducing the risks of emotional numbing, overmodulation, avoidance, and dissociation that would prevent adequate emotional engagement.

These effects may hold special importance for traumatized adolescents, for whom difficulties in treatment adherence, dropouts, and motivation to engage and remain in treatment are pronounced [20, 23, 46]. In particular, the attenuation of overwhelming emotional reactions that could lead to impulsive withdrawal from treatment or harmful avoidance/coping behaviors could be of great benefit in treating traumatized adolescents who often have challenges in emotion regulation [47]. Furthermore, as elaboration, involvement in therapy, and maintaining an appropriate level of emotional engagement appear key to processing of traumatic experiences and symptom reduction in trauma-focused treatment of adolescents [20, 33, 48], effects of MDMA that promote disclosure and engagement and reduce avoidance could enhance treatment efficacy.

Second, overly negative, maladaptive beliefs and appraisals of the traumatic event and its sequelae are closely associated with PTSD symptoms among adolescents [49, 50] and improvement in such cognitions appears to be a mechanism of change involved in many forms of treatment for PTSD among both adults and adolescents [51, 52]. Reappraising the traumatic event, its characteristics, and consequences both under the acute influence of MDMA and in integrative sessions could aid in disconfirming and changing these problematic cognitions. In particular, feelings of safety and ability to confront traumatic material during MDMA sessions [53] may disconfirm beliefs of the world as a wholly dangerous place and the self as incompetent and weak, common to traumatized children and adolescents [54]. As MDMA promotes empathy and prosociality [41, 55, 56], it may reduce effects of perceived social rejection [57], and appears to sometimes promote insights and radical changes in perspectives [53, 58]. Processing trauma during MDMA sessions could thus also affect particularly challenging posttraumatic emotions like shame and guilt.

Third, MDMA appears to enhance fear extinction and/or disrupt fear memory reconsolidation [59,60,61,62,63], processes central to treatment of PTSD by psychological interventions [51, 64, 65]. In particular, MDMA may foster better inhibitory learning [66, 67] and affect reconsolidation because of the greater expectancy violation (or prediction error) induced by its mood-enhancing, fear attenuating, and prosocial effects [42, 68] as well as effects on recollection of negative memories [63, 69]. More effective fear extinction could mean better and faster relief from symptoms when adolescent patients confront their traumatic memories under MDMA. Shorter overall treatment duration or more immediately obvious improvement in symptoms would be important for adolescents whose patience and motivation for treatment is likely to fluctuate.

Fourth, therapeutic alliance has been found a key factor in the success of trauma-focused treatment of adolescents [70] and in reducing dropouts [28, 71]. Establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship may be especially challenging when working with adolescent patients who have experienced interpersonal trauma and the associated deep betrayal of trust [72]. MDMA may aid in strengthening the therapeutic alliance by promoting increased emotional empathy, trust, and closeness [42, 43, 55, 56]. The therapeutic relationship potentially strengthened by the effects of MDMA could also act as a corrective experience for negative beliefs about other people and their trustworthiness. Direct evidence of the post-acute effects of MDMA on therapeutic alliance is limited to clinical observations, however (e.g., [73, 74]).

Fifth, effects of MDMA-AP that go beyond PTSD symptoms may also hold relevance for potential use in adolescents. Though trials of MDMA-AP focus on PTSD symptoms, they have also found anti-depressive effects [2, 75], significant for adolescents among whom PTSD has very high comorbidity with depression [76]. To the extent that MDMA-AP promotes change in trauma-related cognitive processes such as maladaptive appraisals and trauma memory qualities through effects described above, its therapeutic effects for adolescent posttraumatic psychopathology could extend beyond PTSD symptoms [54, 77]. Trials of MDMA-AP for PTSD in adults have not included measures of changes in these processes so far, so comparisons with existing treatments are not possible. Adult trials do, however, suggest that MDMA-AP treatment may also help with problematic alcohol use [78] and improve sleep quality [79], both of which are significant issues in relation to PTSD in adolescents [80, 81].

In sum, we have identified five potential benefits of MDMA-AP for the treatment of adolescents with PTSD: MDMA-AP may (1) reduce avoidance and enable trauma processing, (2) aid in the reappraisal of beliefs, (3) enhance fear extinction, (4) strengthen therapeutic alliance, and (5) have beneficial effects beyond relief of PTSD symptoms. These potential benefits are generic to MDMA-AP, but some may be particularly useful in the treatment of adolescents. For example, as therapeutic alliance is important to successful trauma therapy and is hard to establish with adolescents, a form of treatment that would enhance this process would potentially be more effective in adolescents than in adults. In addition, treatment at a younger age may reduce lifetime disease burden and costs to adolescents and society, while saving quality-adjusted life years [82, 83].

Considerations and adaptations

In MDMA-AP, MDMA itself is typically framed as a “therapeutic adjunct” or “catalyst” to a psychotherapeutic process [84, 85]. Thus, despite involving psychopharmacology, MDMA-AP would be a psychological intervention in the first place. Recently, arguments have been made that the psychotherapy component of MDMA-AP has received inadequate attention [6]

In most trials so far, the psychotherapy or psychological support component of MDMA-AP has followed the largely non-directive and flexible approach described in A Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Disorder [85], written mainly by Michael C. Mithoefer and published by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. This approach and manual were developed primarily based on early work with psychedelics and MDMA, especially that of LSD psychotherapy pioneer Stanislav Grof [86], rather than on theories or treatment modalities specific to PTSD [85]. Accordingly, although it acknowledges similarities with approaches like PE and cognitive restructuring, it also includes elements like focused bodywork and therapeutic use of music that are not found in other PTSD treatments.

Overall, rather than focusing on specific techniques and treatment elements, the manual strongly emphasizes a non-directive approach trusting the patient’s “inner healing intelligence” and “innate wisdom about their own healing process” [85]. It defines core elements of MDMA-AP but allows much leeway for “individual therapist teams to include therapeutic interventions based on their own training, experience, intuition, and clinical judgment” [85]. Accordingly, the manual suggests that “the successful use of MDMA in therapy depends on the ‘sensitivity and talent of the therapist who employs [it]’ (Grinspoon and Doblin, 2001)” [85]. This approach may have its benefits, for example in terms of flexibility in responding to patient needs. However, for TF-CBT, a clearly structured, defined, and manualized therapy, studies have found that therapist characteristics such as theoretical orientation, professional background, and clinical experience do not appear to contribute to the efficacy of PTSD treatment in children and adolescents [87, 88]. A more defined and specified format might lead to more uniform efficacy, less dependent on therapist characteristics, for MDMA-AP among adolescents, too, although this remains a hypothesis to be tested at this stage.

Considering what we know about how adolescents heal from posttraumatic symptoms and how current psychological treatments work, the psychotherapeutic component of MDMA-AP can probably be refined. In the potential application of MDMA-AP for adolescents, researchers and clinicians can look to existing adolescent adaptations of trauma-focused treatments for inspiration in several areas.

First, existing treatments like developmentally adapted CPT and PE-A stress the importance of motivation building when treating PTSD among (older) adolescents [20, 23]. Compared with children, adolescents’ motivation to engage and remain in treatment depends more strongly on the adolescents themselves than on their parents, but compared with adults, their motivation is more likely to fluctuate. Strive for autonomy combined with PTSD-related avoidance can lead to ambivalence toward treatment for traumatized adolescents [46], contributing to drop-out and premature treatment cessation [26, 71]. A motivational interview, openly discussing the impact of the trauma and the advantages and disadvantages of treatment, as well as actively challenging problematic ideas about therapy may be valuable avenues to prevent dropouts and maintain motivation in tailoring MDMA-AP for adolescents [20, 46]. The importance of detailed, age-appropriate psychoeducation (of trauma and trauma symptoms, the treatment plan and its rationale, and even issues like rights and justice) for motivation and collaboration is also emphasized by all trauma-focused treatments (e.g. [20]).

Second and relatedly, the development of a strong therapeutic alliance and relying on youth, rather than therapist, evaluations of its quality appear especially important for successful PTSD treatment among adolescents [70, 71, 89], and is emphasized in several treatment modalities, especially TF-CBT [19]. Therapeutic alliance and trust are already set out as core elements in MDMA-AP [85], but even more time and effort should probably be focused on developing the therapeutic alliance when working with adolescents in general, and especially when working with adolescents exposed to early interpersonal trauma [72]. Based on research findings and concerns young people have about trauma treatment, this time should especially be spent on emphasizing and enhancing the collaborative nature of the work ahead, addressing trust and confidentiality issues, and building rapport, while carefully attending to the adolescent’s perspective and demonstrating empathy and warmth [90,91,92,93]. The groundwork for a successful alliance will undoubtedly be laid in the initial non-drug preparatory sessions, but as pointed out before, MDMA sessions could hypothetically further strengthen the therapeutic alliance throughout the therapy.

Third, traumatized youth are likely to experience difficulties in emotion regulation [47]. Combined with the intense emotional life and rapid mood changes of all adolescents, and elevated potential to react to intense emotions with self-harm or substance abuse, this may call for more focus on emotion and behavior management techniques during treatment. The only regulation technique presented in the current MDMA-AP manual is diaphragmatic breathing [85]. In developing MDMA-AP for adolescents, interventions and techniques for emotion and behavior regulation could be adapted from, e.g., dialectical behavior therapy for PTSD [94], as was done for D-CPT [23], or from the first phase of the TF-CBT protocol [19]. Such techniques would also be helpful for adolescents suffering from PTSD who experience significant dissociative symptoms [95]. If risks of symptom exacerbation or problematic coping methods during or after the coming treatment sessions appear elevated for a particular adolescent patient, a crisis coping plan could be prepared beforehand [20].

Fourth, adolescents tend to be more impulsive [96], less able to sustain attention [97], and more distractible [98], suggesting they may need additional support to maintain therapeutic focus and reduce avoidance. This might conflict with the non-directive approach prescribed in the MDMA-AP manual where listening and presence are the main activities of the therapist. Therapists are instructed to employ “invitation rather than direction” and “minimal encouragement” [85] during MDMA sessions, although guidance or redirection is suggested in some circumstances. In adolescents, for some part of the MDMA session(s), deliberate, systematic, and gently guided exploration of trauma-related memories, thoughts, and emotions might be preferable to trusting the “inner healing intelligence” [85] and the patient’s self-direction. Here, the emphasis in especially NET [22, 99] and PE-A [20] on coherent narration of the traumatic memory and integration of autobiographical, temporal, and spatial information into a consistent declarative representation of the event(s) may be a valuable consideration when developing and trialing MDMA-AP for adolescents. In both approaches to imaginal exposure, the therapist guides and encourages the participant to focus on all aspects of the traumatic memories, including the most avoided and troubling parts that may be characterized by lack of coherence or organization and dominated by sensory and emotional elements. Explicitly observing similarities in emotions, thoughts and physical reactions that arise during treatment with those at the time of trauma could be a further valuable exercise during MDMA sessions and promote insight [22].

Besides potentially better organizing the traumatic memories [20,21,22], comprehensively activating and exploring them in a safe and empathetic encounter (both elements potentially strengthened by MDMA) can lead to corrective experiences and learning that trauma-affected maladaptive perceptions and beliefs are inaccurate, overly negative and catastrophizing. This active exposure-based work requires patience and resolve from therapists to let and even encourage adolescents to explore their traumatic memories, including their worst moments—a process that is bound to involve difficult emotions and reactions, hopefully made more manageable with the help of MDMA. Due especially to enhanced fear extinction and disrupted fear memory reconsolidation, several researchers have suggested the MDMA-induced state would be well suited for exposure-based work [3, 8, 100], but direct evidence awaits future (comparative) trials.

Especially when working with adolescents with multiple traumatic experiences, adopting the sort of life story perspective emphasized by NET, where traumatic experiences are explicitly placed in their own place and time and positive memories and experiences are also discussed could be valuable for the therapeutic process overall, including both MDMA and integrative sessions [22]. For exploring positive memories as sources of resilience and meaning, the acute effects of MDMA may be mixed, as there is evidence of enhanced vividness and positive affect when thinking about positive autobiographical memories [43] but also of amnestic effects on detailed positive recollection [69].

Fifth, as part of the therapeutic process, adolescents might need more support in dealing with social and developmental challenges and barriers to treatment not directly related to their trauma, as well as in practical integration of treatment benefits and separation from the therapist. Here, elements such as systematic evaluation of adolescent (and family) difficulties besides PTSD, plans for coping with crises and relapses, and final projects could be adapted from the more extensive case management and relapse prevention components included in PE-A, for example [20].

Finally, laws and definitions vary, but in many countries, older adolescents can make decisions on their medical care and give informed consent for research themselves (they are considered “mature minors” [101]; see also [102] for criticism and [103] for overview), and even ask for their parents not be informed of their choices. However, this does not mean that involvement of parents or guardians in the decision-making and treatment process would be unwelcome. On the contrary, in many cases, the involvement of parents or guardians could make an important positive contribution, including less likelihood of drop-out [28]. Of existing treatments, TF-CBT dedicates up to half of the treatment sessions as parent or conjoint sessions and offers many ideas about parent involvement [19]. In PE-A, tailored family involvement is also emphasized [20], while in D-CPT, sessions with caregivers are optional [23]. At the very minimum in MDMA-AP for adolescents, ample psychoeducation should be directed at parents and families so that they may best support the adolescent during and after treatment. Conjoint (non-drug) sessions with parents especially in the early and closing stages of the treatment could be considered, or parents could join in the concluding parts of MDMA sessions when drug effects have waned, as the current manual suggests for significant others [85].

On the other hand, adolescence is also a time of struggling for independence and autonomy and even conflict with parents. Some older adolescents may not want to involve their parents deeply in the treatment or share their intimate feelings or experiences with them [23]. Their wishes should be respected, and confidentiality maintained, barring legal or ethical requirements to disclose information in special circumstances of course [46]. With adolescents, it is their own motivation to accept treatment and remain in it that is crucially important and needs to be supported [23].

In sum, the unique characteristics of adolescents call for a reconsideration of the psychotherapeutic component of MDMA-AP, perhaps even developing an entirely new protocol for it. Here, we have argued for focusing on (1) ways of reinforcing motivation, (2) the development of a strong therapeutic alliance, (3) additional emotion and behavior management techniques, (4) more directive, exposure-based methods during MDMA sessions, (5) more support for concomitant challenges and integrating treatment benefits, and 6) involving family in treatment. These suggested adaptations are, admittedly, based on reasoning from indirect evidence. Clinical trials with a comparative or dismantling focus are needed to determine whether they are, in fact, useful or necessary. Alternatively, we could study the potential of directly combining MDMA with existing, evidence-based treatments already adapted to adolescents, such as TF-CBT or PE-A, as others have suggested for adults [3, 8] and trialed with good results for cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy [104].

Potential risks particular to adolescents

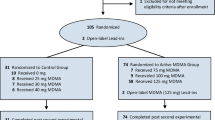

The average age of participants in recent trials of MDMA-AP has been around forty [2, 34]. Thus, their findings regarding safety and possible risks cannot be directly applied to 14–17-year-olds, and potential risks particular to adolescents should be considered.

First, the acute physiological effects of MDMA at typical doses used in therapeutic research, 75–125 mg, are well established among adult healthy volunteers [105] and include elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature. However, to our knowledge, human research with MDMA has never been carried out in adolescents. In young adults of age 18–45 years, Studerus et al. [106] did find younger age to predict higher heart rate elevation, although the authors did not consider this of much clinical or practical relevance. At face value, there seems to be no specific reason to consider these typical physiological effects or common side effects such as muscle tightness, sweating, headaches, or nausea [2, 4] significantly more or less problematic for adolescents than for adults, provided adequate pre-screening for risk factors such as cardiovascular disease is in place. Still, “young people are often not the same as adults in terms of response to […] medications and their side effects.” [107]. Any clinical research on MDMA in adolescents should start from safety and tolerability. The lack of age-specific dosing information is a common unmet need in pediatric psychopharmacology [108], and differences in pharmacokinetics, for instance, may extend beyond the smaller size of adolescents.

Second, regarding unpleasant psychological effects, Studerus et al. [106] found high neuroticism and trait anxiety to predict feelings of dread and impaired control and cognition as reactions to MDMA among healthy adults. Anxiety seems to be the most common acute psychological adverse effect in MDMA-AP for PTSD [4]. Some participants also experience anxiety and low mood post-acutely and in the longer term. We agree with Breeksema et al. [4] on the importance of studying whether such effects are related to typical temporary emotional distress related to therapeutic processing of trauma or are better viewed as post-acute adverse effects due to MDMA. In any case, these findings could have relevance for adolescents, as neuroticism and negative emotionality is typically higher in adolescence before decreasing in young adulthood [109, 110]. Further, a few adverse events related to suicidality were reported in the latest Phase 3 trial of MDMA-AP among adults, in both the MDMA and placebo groups, although suicidal behavior only occurred in the placebo group [2]. Accordingly, the elevated incidence of self-harm among adolescents as well as suicidality in older adolescents, especially pronounced for those with histories of abuse or suffering from PTSD [111, 112] should also be considered. Although (trauma-focused) treatment of PTSD among adolescents has not been found to exacerbate suicidal ideation and may indeed reduce it [64, 113], close monitoring of adolescents throughout treatment and perhaps especially in the sub-acute phase is called for, with special attention to potential adverse events involving self-harm and suicidality.

Third, the potential toxicity of MDMA to the (developing) brain and possible cognitive harms are an important question for therapeutic use among adolescents. Heavy adult recreational MDMA users (typically with lifetime consumption in the hundreds of MDMA tablets) exhibit deficits in several areas of cognitive function, including attention and working and short-term memory, although it remains unclear whether these deficits are exclusively caused by MDMA use [114]. At high doses, MDMA is neurotoxic to animals, including non-human primates, leading to loss of neuronal bodies and terminals [115]. Some animal studies also suggest long-term cognitive deficits from high-dose MDMA exposure in adolescence [116, 117], although other studies did not find effects on cognition [114]. Findings on whether adolescent animals are less or more susceptible to MDMA-induced neurotoxicity than adults are mixed [118,119,120,121,122]. As most animal studies involve (repeated) high doses, their relevance for a few administrations of smaller, therapeutic doses is unclear. A systematic review of 90 animal experiments found no evidence that MDMA produces cognitive impairments in animals at doses below 3 mg/kg [114], whereas clinical dosages in humans are about 1 to 2 mg/kg. In their review, Pantoni and Anagnostaras [114] conclude that “overall, the preclinical evidence of MDMA-induced cognitive deficits is weak” and that “it is unlikely that less than 3 mg/kg of pure MDMA poses significant danger to neurological health if administered infrequently and in a controlled setting.” Still, as direct evidence in adolescents is lacking, it would be important to study potential cognitive harms in any clinical trial of MDMA-AP for adolescents.

Fourth, although dependence is very rare [123, 124], MDMA has some misuse potential among both adults and adolescents. Among adolescents with substance use disorders, there are further indications that those with PTSD are more likely to use MDMA illicitly, and that their MDMA use is associated with coping and self-medication motives, but also avoidance-type symptoms specifically [125, 126]. Trials of MDMA-AP with adults have not reported increased use of MDMA or indications of abuse potential among participants [2, 4]. However, increased risk-taking, reward sensitivity, and impulsivity in adolescence [96, 127, 128] may mean that the risk of misuse or wish to use MDMA beyond the clinical setting once aware of its effects could be elevated for adolescents, as compared with especially older adults [129].

Fifth, history presents us with examples of (by today’s standards) unethical psychopharmacological research on children, including with psychedelics [130] and stimulants [131]. In current MDMA-AP research with adults, at least one serious instance of unethical behavior has occurred [132]. Any clinical use or research involving MDMA in minors must adhere to high ethical standards and be cognizant of the complex ethical issues involved in child and adolescent psychopharmacology [103, 133], further complicated by the altered state of consciousness produced by MDMA. Here too, a more explicitly specified and structured format for the psychotherapeutic component of MDMA-AP could help in further defining expected and appropriate forms for adolescent-therapist interaction, especially during the dependent and vulnerable MDMA-induced state [4, 6].

Overall, a recent review suggested adverse events and harms may have been poorly defined and inadequately assessed in MDMA-AP studies [4]. Any studies among adolescents should pay close attention to extensively and openly reporting adverse events and harms. At the same time, any side effects or risks that do emerge must be considered in relation to how effective MDMA-AP turns out to be for addressing the enormous burden of untreated PTSD among adolescents.

Conclusions

As many adolescents suffer from PTSD, and current evidence-based treatments leave room for improvement, there is a need for new approaches to address PTSD among adolescents. Considering evidence of efficacy among adults, and what we know about how MDMA might enhance treatment, we have argued here that it makes sense to study MDMA-AP for PTSD in adolescents. As a developmental period of great change and reorganization, adolescence represents both challenges and opportunities for mental health treatment. We have suggested potential modifications and adaptations to especially the psychotherapeutic component of MDMA-AP that could be useful for adolescents, and discussed potential risks and concerns specific to them, summarized in Table 1.

If MDMA-assisted psychotherapy becomes an approved treatment for adults, it may be possible in many countries to extend use to adolescents, even if no studies among them have been carried out. For years, experts on pediatric psychopharmacology have emphasized and criticized the “frequent off-label prescription of medications to children and adolescents based exclusively on data from [RCT’s] involving adult patients” [108]. As Tan and Koelch [134] noted, due to the prominent ethical concerns and rigorous requirements for psychopharmacological research among minors, they are, paradoxically, sometimes so well protected against research that there is little data available about the safety and effectiveness of psychiatric medications they are commonly described. Accordingly, we should try to avoid a situation where MDMA-AP is applied to adolescents in an off-label and ad hoc basis, with the assumption that results among adults also apply to them.

Especially when psychopharmacology is involved, “for youth populations it is not sufficient to extrapolate efficacy or side effect data from adult studies” [107]. We should face the ethical and practical challenges and carry out the research to ensure that if MDMA-AP is used among adolescents, this practice is evidence-based. If MDMA-AP is approved for adults, trials with adolescents using the current treatment protocol are expected. We hope that these possible future trials will be complemented by comparative studies that vary and adapt the psychotherapeutic component, and that together they will either provide such an evidence base or show that MDMA-AP should not be used for adolescents in any form.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (2023) Announcement: prior positive results confirmed in MAPS-sponsored, philanthropy-funded phase 3 trial. https://maps.org/2023/01/05/prior-positive-results-confirmed/. Accessed 1 July 2023

Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A et al (2021) MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

Bedi G, Cotton SM, Guerin AA, Jackson HJ (2023) MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: the devil is in the detail. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 57:476–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674221127186

Breeksema JJ, Kuin BW, Kamphuis J et al (2022) Adverse events in clinical treatments with serotonergic psychedelics and MDMA: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Psychopharmacol 36:1100–1117. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811221116926

Halvorsen JØ, Naudet F, Cristea IA (2021) Challenges with benchmarking of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Nat Med 27:1689–1690. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01525-0

McNamee S, Devenot N, Buisson M (2023) Studying harms is key to improving psychedelic-assisted therapy—participants call for changes to research landscape. JAMA Psychiat. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0099

Mitchell J, Coker A, Yazar-Klosinski B (2021) Reply to: caution at psychiatry’s psychedelic frontier and challenges with benchmarking of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Nat Med 27:1691–1692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01526-z

Rothbaum BO, Maples-Keller JL (2023) The promise of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in combination with prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol 48:255–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01381-7

Fedewa A, Richardson M, Watson A (2022) Psychedelic-assisted therapy for youth and what we know from adult studies. Turkish International Journal of Special Education and Guidance & Counselling 11:1–9. https://www.tijseg.org/index.php/tijseg/article/view/153

Rajwani K (2022) Should adolescents be included in emerging psychedelic research? Canadian Bioeth 5:36–43. https://doi.org/10.7202/1089784ar

Landolt MA, Schnyder U, Maier T et al (2013) Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents: a national survey in Switzerland: trauma exposure and PTSD in Swiss adolescents. J Trauma Stress 26:209–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21794

McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED et al (2013) Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:815-830.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011

Alisic E, Zalta AK, van Wesel F et al (2014) Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 204:335–340. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227

Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ (2007) Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:577. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577

Trickey D, Siddaway AP, Meiser-Stedman R et al (2012) A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 32:122–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001

Gillies D, Maiocchi L, Bhandari AP et al (2016) Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012371

Thielemann JFB, Kasparik B, König J et al (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl 134:105899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105899

Xiang Y, Cipriani A, Teng T et al (2021) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Mental Health 24:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2021-300346

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E (2017) Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press

Foa EB, Chrestman KR, Gilboa-Schechtman E (2009) Prolonged exposure therapy for adolescents with PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences: therapist guide. Oxford University Press

Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T (2011) Narrative exposure therapy: a short-term treatment for traumatic stress disorders, 2nd edn. Hogrefe Publishing

Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T (2017) Narrative exposure therapy for children and adolescents (KIDNET). In: Landolt MA, Cloitre M, Schnyder U (eds) Evidence-based treatments for trauma related disorders in children and adolescents. Springer International Publishing, pp 227–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46138-0_11

Matulis S, Resick PA, Rosner R, Steil R (2014) Developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy for adolescents suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual or physical abuse: a pilot study. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 17:173–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0156-9

Resick PA, Monso CM, Chard KM (2016) Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD–a comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press

Morina N, Koerssen R, Pollet TV (2016) Interventions for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev 47:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.006

Simmons C, Meiser-Stedman R, Baily H, Beazley P (2021) A meta-analysis of dropout from evidence-based psychological treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children and young people. Eur J Psychotraumatol 12:1947570. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1947570

Skar A-MS, Braathu N, Jensen TK, Ormhaug SM (2022) Predictors of nonresponse and drop-out among children and adolescents receiving TF-CBT: investigation of client-, therapist-, and implementation factors. BMC Health Serv Res 22:1212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08497-y

Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK (2018) Investigating treatment characteristics and first-session relationship variables as predictors of dropout in the treatment of traumatized youth. Psychother Res 28:235–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1189617

Yasinski C, Hayes AM, Alpert E et al (2018) Treatment processes and demographic variables as predictors of dropout from trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for youth. Behav Res Ther 107:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.05.008

Foa EB, McLean CP, Capaldi S, Rosenfield D (2013) Prolonged exposure vs supportive counseling for sexual abuse-related PTSD in adolescent girls: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310:2650. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.282829

Peltonen K, Kangaslampi S (2019) Treating children and adolescents with multiple traumas: a randomized clinical trial of narrative exposure therapy. Eur J Psychotraumatol 10:1558708. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1558708

Rosner R, Rimane E, Frick U et al (2019) Effect of developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy for youth with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual and physical abuse: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat 76:484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4349

Hayes AM, Yasinski C, Grasso D et al (2017) Constructive and unproductive processing of traumatic experiences in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth. Behav Ther 48:166–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.06.004

Jerome L, Feduccia AA, Wang JB et al (2020) Long-term follow-up outcomes of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: a longitudinal pooled analysis of six phase 2 trials. Psychopharmacology 237:2485–2497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05548-2

Gutner CA, Gallagher MW, Baker AS et al (2016) Time course of treatment dropout in cognitive–behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 8:115–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000062

Schnurr PP, Chard KM, Ruzek JI et al (2022) Comparison of prolonged exposure vs cognitive processing therapy for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder among us veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2136921. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36921

Dolder PC, Müller F, Schmid Y et al (2018) Direct comparison of the acute subjective, emotional, autonomic, and endocrine effects of MDMA, methylphenidate, and modafinil in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology 235:467–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4650-5

Gamma A (2000) 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) modulates cortical and limbic brain activity as measured by [H215O]-PET in healthy humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 23:388–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00130-5

Bedi G, Hyman D, de Wit H (2010) Is ecstasy an “empathogen”? effects of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on prosocial feelings and identification of emotional states in others. Biol Psychiat 68:1134–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.003

Kamilar-Britt P, Bedi G (2015) The prosocial effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): controlled studies in humans and laboratory animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 57:433–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.016

Hysek CM, Schmid Y, Simmler LD et al (2014) MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9:1645–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst161

Stewart L, Ferguson B, Morgan C et al (2014) Effects of ecstasy on cooperative behaviour and perception of trustworthiness: a naturalistic study. J Psychopharmacol 28:1001–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881114544775

Carhart-Harris RL, Wall MB, Erritzoe D et al (2014) The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD-fMRI responses to favourite and worst autobiographical memories. Int J Neuropsychopharm 17:527–540. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145713001405

Van Wel JHP, Kuypers KPC, Theunissen EL et al (2012) Effects of acute MDMA intoxication on mood and impulsivity: role of the 5-HT2 and 5-HT1 receptors. PLoS ONE 7:e40187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040187

Baggott MJ, Coyle JR, Siegrist JD et al (2016) Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on socioemotional feelings, authenticity, and autobiographical disclosure in healthy volunteers in a controlled setting. J Psychopharmacol 30:378–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115626348

Vogel A, Rosner R (2020) Lost in transition? Evidence-based treatments for adolescents and young adults with posttraumatic stress disorder and results of an uncontrolled feasibility trial evaluating cognitive processing therapy. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 23:122–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00305-0

Villalta L, Smith P, Hickin N, Stringaris A (2018) Emotion regulation difficulties in traumatized youth: a meta-analysis and conceptual review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:527–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1105-4

Ovenstad KS, Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK (2022) The relationship between youth involvement, alliance and outcome in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychother Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2123719

Hiller RM, Meiser-Stedman R, Elliott E et al (2021) A longitudinal study of cognitive predictors of (complex) post-traumatic stress in young people in out-of-home care. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 62:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13232

Mitchell R, Brennan K, Curran D et al (2017) A meta-analysis of the association between appraisals of trauma and posttraumatic stress in children and adolescents: meta-analysis of trauma appraisals in children. J Trauma Stress 30:88–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22157

Alpert E, Shotwell Tabke C, Cole TA et al (2023) A systematic review of literature examining mediators and mechanisms of change in empirically supported treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 103:102300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102300

Kangaslampi S, Peltonen K (2022) Mechanisms of change in psychological interventions for posttraumatic stress symptoms: A systematic review with recommendations. Curr Psychol 41:258–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00478-5

Barone W, Beck J, Mitsunaga-Whitten M, Perl P (2019) Perceived benefits of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy beyond symptom reduction: qualitative follow-up study of a clinical trial for individuals with treatment-resistant PTSD. J Psychoactive Drugs 51:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1580805

de Haan A, Landolt MA, Fried EI et al (2020) Dysfunctional posttraumatic cognitions, posttraumatic stress and depression in children and adolescents exposed to trauma: a network analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 61:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13101

Bershad AK, Miller MA, Baggott MJ, de Wit H (2016) The effects of MDMA on socio-emotional processing: does MDMA differ from other stimulants? J Psychopharmacol 30:1248–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116663120

Kuypers KP, Dolder PC, Ramaekers JG, Liechti ME (2017) Multifaceted empathy of healthy volunteers after single doses of MDMA: a pooled sample of placebo-controlled studies. J Psychopharmacol 31:589–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117699617

Frye CG, Wardle MC, Norman GJ, de Wit H (2014) MDMA decreases the effects of simulated social rejection. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 117:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.030

Sola EM (2017) MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: a thematic analysis of transformation in combat veterans. Dissertation, California Institute of Integral Studies. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2054006157

Maples-Keller JL, Norrholm SD, Burton M et al (2022) A randomized controlled trial of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and fear extinction retention in healthy adults. J Psychopharmacol 36:368–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811211069124

Young MB, Norrholm SD, Khoury LM et al (2017) Inhibition of serotonin transporters disrupts the enhancement of fear memory extinction by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Psychopharmacology 234:2883–2895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4684-8

Vizeli P, Straumann I, Duthaler U et al (2022) Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on conditioned fear extinction and retention in a crossover study in healthy subjects. Front Pharmacol 13:906639. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.906639

Hake HS, Davis JKP, Wood RR et al (2019) 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) impairs the extinction and reconsolidation of fear memory in rats. Physiol Behav 199:343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.12.007

Sarmanlu M, Kuypers KPC, Vizeli P, Kvamme TL (2024) MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: growing evidence for memory effects mediating treatment efficacy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 128:110843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2023.110843

Brown LA, Zandberg LJ, Foa EB (2019) Mechanisms of change in prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: implications for clinical practice. J Psychother Integr 29:6–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000109

Smith NB, Doran JM, Sippel LM, Harpaz-Rotem I (2017) Fear extinction and memory reconsolidation as critical components in behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder and potential augmentation of these processes. Neurosci Lett 649:170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.01.006

Craske MG, Liao B, Brown L, Vervliet B (2012) Role of inhibition in exposure therapy. J Exp Psychopathol 3:322–345. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.026511

Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC et al (2014) Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther 58:10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

Lebois LAM, Seligowski AV, Wolff JD et al (2019) Augmentation of extinction and inhibitory learning in anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 15:257–284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095634

Doss MK, Weafer J, Gallo DA, de Wit H (2018) MDMA impairs both the encoding and retrieval of emotional recollections. Neuropsychopharmacol 43:791–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.171

Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK, Wentzel-Larsen T, Shirk SR (2014) The therapeutic alliance in treatment of traumatized youths: relation to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 82:52–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033884

de Haan AM, Boon AE, de Jong JTVM et al (2013) A meta-analytic review on treatment dropout in child and adolescent outpatient mental health care. Clin Psychol Rev 33:698–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.04.005

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Kliethermes M, Murray LA (2012) Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Abuse Negl 36:528–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.007

Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB (1986) Can drugs be used to enhance the psychotherapeutic process? APT 40:393–404. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1986.40.3.393

Oehen P, Gasser P (2022) Using a MDMA- and LSD-group therapy model in clinical practice in Switzerland and highlighting the treatment of trauma-related disorders. Front Psychiatry 13:863552. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.863552

Mithoefer MC, Feduccia AA, Jerome L et al (2019) MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials. Psychopharmacology 236:2735–2745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05249-5

Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R et al (2003) Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the national survey of adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:692–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692

Davis RS, Halligan SL, Meiser-Stedman R et al (2023) A longitudinal investigation of the relationship between trauma-related cognitive processes and internalising and externalising psychopathology in young people in out-of-home care. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51:485–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-01005-0

Nicholas CR, Wang JB, Coker A et al (2022) The effects of MDMA-assisted therapy on alcohol and substance use in a phase 3 trial for treatment of severe PTSD. Drug Alcohol Depend 233:109356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109356

Ponte L, Jerome L, Hamilton S et al (2021) Sleep quality improvements after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 34:851–863. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22696

Adams ZW, Danielson CK, Sumner JA et al (2015) Comorbidity of PTSD, major depression, and substance use disorder among adolescent victims of the spring 2011 tornadoes in Alabama and Joplin, Missouri. Psychiatry 78:170–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2015.1051448

Kovachy B, O’Hara R, Hawkins N et al (2013) Sleep disturbance in pediatric PTSD: current findings and future directions. J Clin Sleep Med 09:501–510. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.2678

Danese A, McLaughlin KA, Samara M, Stover CS (2020) Psychopathology in children exposed to trauma: detection and intervention needed to reduce downstream burden. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3073

Mavranezouli I, Megnin-Viggars O, Trickey D et al (2020) Cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions for children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder. Child Psychol Psychiatry 61:699–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13142

Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT et al (2011) The safety and efficacy of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol 25:439–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110378371

Mithoefer M (2017) A manual for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Version 8.1. https://maps.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/MDMA-Assisted-Psychotherapy-Treatment-Manual-V8.1-22AUG2017.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2023

Grof S (2008) LSD Psychotherapy, 4th Edn. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. ISBN 0979862205

Grainger L, Thompson Z, Morina N et al (2022) Associations between therapist factors and treatment efficacy in randomized controlled trials of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress 35:1405–1419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22840

Pfeiffer E, Ormhaug SM, Tutus D et al (2020) Does the therapist matter? Therapist characteristics and their relation to outcome in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol 11:1776048. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1776048

Ovenstad KS, Jensen TK, Ormhaug SM (2022) Four perspectives on traumatized youths’ therapeutic alliance: correspondence and outcome predictions. Psychother Res 32:820–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2021.2011983

Fjermestad KW, Føreland Ø, Oppedal SB et al (2021) Therapist alliance-building behaviors, alliance, and outcomes in cognitive behavioral treatment for youth anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 50:229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1683850

Karver MS, De Nadai AS, Monahan M, Shirk SR (2018) Meta-analysis of the prospective relation between alliance and outcome in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 55:341–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000176

Ovenstad KS, Ormhaug SM, Shirk SR, Jensen TK (2020) Therapists’ behaviors and youths’ therapeutic alliance during trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 88:350–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000465

Truss K, Liao Siling J, Phillips L et al (2023) Barriers to young people seeking help for trauma: a qualitative analysis of Internet forums. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 15:S163–S171. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001344

Bohus M, Dyer AS, Priebe K et al (2013) Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 82:221–233. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348451

Choi KR, Ford JD, Briggs EC et al (2019) Relationships between maltreatment, posttraumatic symptomatology, and the dissociative subtype of PTSD among adolescents. J Trauma Dissociation 20:212–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1572043

Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E et al (2008) Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol 44:1764–1778. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012955

Fortenbaugh FC, DeGutis J, Germine L et al (2015) Sustained attention across the life span in a sample of 10,000: dissociating ability and strategy. Psychol Sci 26:1497–1510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615594896

Hoyer RS, Elshafei H, Hemmerlin J et al (2021) Why are children so distractible? Development of attention and motor control from childhood to adulthood. Child Dev 92:716–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13561

Neuner F, Catani C, Ruf M et al (2008) Narrative exposure therapy for the treatment of traumatized children and adolescents (KidNET): from neurocognitive theory to field intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 17:641–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2008.03.001

Johansen P, Krebs T (2009) How could MDMA (ecstasy) help anxiety disorders? a neurobiological rationale. J Psychopharmacol 23:389–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109102787

Katz AL, Webb SA, Committee on Bioethics et al (2016) Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 138:e20161485. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1485

Iltis AS (2013) Parents, adolescents, and consent for research participation. J Med Philos 38:332–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jht012

Spriggs M (2023) Children and bioethics: clarifying consent and assent in medical and research settings. Br Med Bull 145:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldac038

Monson CM, Wagner AC, Mithoefer AT et al (2020) MDMA-facilitated cognitive-behavioural conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: an uncontrolled trial. Eur J Psychotraumatol 11:1840123. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1840123

Vizeli P, Liechti ME (2017) Safety pharmacology of acute MDMA administration in healthy subjects. J Psychopharmacol 31:576–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117691569

Studerus E, Vizeli P, Harder S et al (2021) Prediction of MDMA response in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Psychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881121998322

Thompson A, Yung AR (2020) Psychopharmacology in youth mental health. In: Young AR, Cotter J, McGorry PD (eds) Youth mental health: approaches to emerging mental Ill-health in young people. Routledge, pp 237–254. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429285806

Persico AM, Arango C, Buitelaar JK et al (2015) Unmet needs in paediatric psychopharmacology: present scenario and future perspectives. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25:1513–1531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.009

Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL (2005) Personality development: stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol 56:453–484. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK (2009) Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol 118:360–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015125

Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC (2012) Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet 379:2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5

Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Triantafyllou K, Tarrier N (2015) Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:525–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0978-x

Fischer A, Rosner R, Renneberg B, Steil R (2022) Suicidal ideation, self-injury, aggressive behavior and substance use during intensive trauma-focused treatment with exposure-based components in adolescent and young adult PTSD patients. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul 9:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-021-00172-8

Pantoni MM, Anagnostaras SG (2019) Cognitive effects of MDMA in laboratory animals: a systematic review focusing on dose. Pharmacol Rev 71:413–449. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.017087

Costa G, Gołembiowska K (2022) Neurotoxicity of MDMA: main effects and mechanisms. Exp Neurol 347:113894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113894

Compton DM, Selinger MC, Westman E, Otero P (2011) Differentiation of MDMA or 5-MeO-DIPT induced cognitive deficits in rat following adolescent exposure. Psychol Neurosci 4:157–169. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2011.1.018

Compton DM, Dietrich KL, Esquivel P, Garcia C (2017) Longitudinal examination of learning and memory in rats following adolescent Exposure to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine or 5-methoxy-N, N-diisopropyltryptamine. JBBS 07:371–398. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2017.79028

Bates MLS, Trujillo KA (2021) Use and abuse of dissociative and psychedelic drugs in adolescence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 203:173129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2021.173129

Broening HW, Bacon L, Slikker W Jr (1994) Age modulates the long-term but not the acute effects of the serotonergic neurotoxicant 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 271:285–293

Chitre NM, Bagwell MS, Murnane KS (2020) The acute toxic and neurotoxic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine are more pronounced in adolescent than adult mice. Behav Brain Res 380:112413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112413

Feio-Azevedo R, Costa VM, Barbosa DJ et al (2018) Aged rats are more vulnerable than adolescents to “ecstasy”-induced toxicity. Arch Toxicol 92:2275–2295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-018-2226-8

Klomp A, den Hollander B, de Bruin K et al (2012) The effects of ecstasy (MDMA) on brain serotonin transporters are dependent on age-of-first exposure in recreational users and animals. PLoS ONE 7:e47524. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047524

Degenhardt L, Bruno R, Topp L (2010) Is ecstasy a drug of dependence? Drug Alcohol Depend 107:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.009

Van Amsterdam J, Ramaekers JG, Nabben T, Van Den Brink W (2021) Use characteristics and harm potential of ecstasy in the Netherlands. drugs: education. Prev Policy 28:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1818692

Basedow LA, Kuitunen-Paul S, Wiedmann MF et al (2021) Self-reported PTSD is associated with increased use of MDMA in adolescents with substance use disorders. Eur J Psychotraumatol 12:1968140. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1968140

Basedow LA, Wiedmann MF, Roessner V et al (2022) Coping motives mediate the relationship between PTSD and MDMA use in adolescents with substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract 17:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00329-y

Crone EA, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Peper JS (2016) Annual research review: neural contributions to risk-taking in adolescence-developmental changes and individual differences. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 57:353–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12502

Defoe IN, Dubas JS, Figner B, van Aken MAG (2015) A meta-analysis on age differences in risky decision making: adolescents versus children and adults. Psychol Bull 141:48–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038088

Argyriou E, Um M, Carron C, Cyders MA (2018) Age and impulsive behavior in drug addiction: a review of past research and future directions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 164:106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2017.07.013

Sigafoos J, Green VA, Edrisinha C, Lancioni GE (2007) Flashback to the 1960s: LSD in the treatment of autism. Dev Neurorehabil 10:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13638490601106277

Bradley C (1937) The behavior of children receiving benzedrine. AJP 94:577–585. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.94.3.577

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (2019/2022) Statement: public announcement of ethical violation by former MAPS-sponsored investigators. https://maps.org/2019/05/24/statement-public-announcement-of-ethical-violation-by-former-maps-sponsored-investigators/. Accessed 1 July 2023

Welisch E, Altamirano-Diaz LA (2015) Ethics of pharmacological research involving adolescents. Pediatr Drugs 17:55–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-014-0114-0

Tan JO, Koelch M (2008) The ethics of psychopharmacological research in legal minors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-2-39

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tampere University (including Tampere University Hospital). SK was funded by a personal grant from the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation for some of this work. JZ declares no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK conceived of the article and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. Both authors then wrote and edited the main manuscript text. JZ prepared Table 1. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SK has received modest side income from organizing clinical training in narrative exposure therapy. JZ declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kangaslampi, S., Zijlmans, J. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD in adolescents: rationale, potential, risks, and considerations. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02310-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02310-9