Abstract

Purpose

Robot-assisted surgery has a multi-joint function, which improves manipulation of the deep pelvic region and contributes significantly to perioperative safety. However, the superiority of robot-assisted surgery to laparoscopic surgery remains controversial. This study compared the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery for rectal tumors.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective study included 273 patients with rectal tumors who underwent surgery with anastomosis between 2017 and 2021. In total, 169 patients underwent laparoscopic surgery (Lap group), and 104 underwent robot-assisted surgery (Robot group). Postoperative complications were compared via propensity score matching based on inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW).

Results

The postoperative complication rates based on the Clavien–Dindo classification (Lap vs. Robot group) were as follows: grade ≥ II, 29.0% vs. 19.2%; grade ≥ III, 10.7% vs. 5.8%; anastomotic leakage (AL), 6.5% vs. 4.8%; and urinary dysfunction (UD), 12.1% vs. 3.8%. After adjusting for the IPTW method, although AL rates did not differ significantly between groups, postoperative complications of both grade ≥ II (odds ratio [OR] 0.66, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50–0.87, p < 0.01) and grade ≥ III (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.16–0.53, p < 0.01) were significantly less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group. Furthermore, urinary dysfunction also tended to be less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38–1.00; p = 0.05).

Conclusion

Robot-assisted surgery for rectal tumors provides better short-term outcomes than laparoscopic surgery, supporting its use as a safer approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major disease that affects 19,000 people annually, ranking third among males, second among females, and third in terms of the overall number of deaths worldwide [1]. Colorectal surgery, which is performed via laparotomy, has shifted to laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery with an emphasis on minimally invasive procedures. Rectal cancer surgery is particularly challenging among colorectal surgeries because it necessitates dissection in the narrow pelvic cavity along a more complicated anatomical layer, while preserving the urogenital organs and their associated autonomic nervous systems.

Conventional laparoscopic rectal surgery is difficult because the limited flexibility of forceps prevents their straight-line entry into the narrow pelvic cavity. Two recent multicenter randomized controlled trials revealed that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer has a higher rate of positive surgical resection margins than open surgery [2, 3]. Robot-assisted surgery for rectal tumors is expected to be useful not only in oncological practice but also in terms of postoperative clinical course and anal functional preservation, as it enables precise surgical manipulation within the narrow pelvic cavity with its multi-joint function and three-dimensional (3D) visualization, in addition to the magnification effect of laparoscopic surgery.

Weber et al. first reported robot-assisted colon resection for benign diseases in 2001, and Pigazzi et al. first reported robot-assisted total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in 2006 [4, 5]. Since then, the use of robot-assisted rectal surgery has spread rapidly, with the total number of surgeries using the da Vinci Surgical System® reaching more than 800,000 in 2020. The number of robot-assisted rectal surgeries has dramatically increased in Japan since insurance coverage began in 2018.

Robot-assisted surgery for rectal cancer, particularly in lower cases, is expected to reduce the number of surgical wounds, improve oncological outcomes, accelerate postoperative recovery, and reduce postoperative complications. Wang et al. reported a meta-analysis of the outcomes of robot-assisted and laparoscopic surgeries for rectal cancer and identified lower complication rates with robot-assisted surgery [6]. However, their report also mentioned longer operative periods, and included many reports that did not determine the superiority of robot-assisted surgery. Thus, the advantages of robot-assisted surgery for minimally invasive rectal cancer remain unclear.

Therefore, in this study, we compared the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery for rectal tumors to verify the safety of the robot-assisted approach.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

This was a single-center, retrospective study. All procedures and perioperative management were performed at Gifu University Hospital. Robot-assisted surgeries were performed using the da Vinci robotic system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and all surgeries were performed by four surgeons certified by the National Society for Endoscopic Surgery in Japan. Patients who underwent laparoscopic or robot-assisted resection of rectal tumors between 2017 and 2021 were selected, and those who did not undergo anastomosis were excluded. The patients were divided into a laparoscopic surgery group (Lap group) and robot-assisted surgery group (Robot group).

This study was approved by the Central Ethics Committee of Gifu University (Approval Number: 2019–147).

Outcomes of interest

The following outcomes and parameters were used to compare the two operative approaches. The primary outcome of this study was postoperative complication rates, assessed as Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ II, grade ≥ III, anastomotic leakage (AL), and urinary dysfunction of all grades. The age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS), diabetes mellitus (DM), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), lateral pelvic lymph node (LPL) dissection, tumor size, cT and cN factors, diverting stoma, and preoperative treatment were incorporated as propensity score factors.

Extracted data

The following clinical data were extracted: age, sex, physical status (PS), BMI, presence of DM, and PNI scores as the patient’s clinical background, histopathological findings, tumor size, cTNM stage, and details of preoperative treatment as the oncological factors and operative period, operative blood loss, presence of LPL dissection, number of dissected lymph nodes, presence of diverting stoma, first postoperative bowel movement, postoperative complications, and length of postoperative hospital stay as the perioperative factors.

Definition of each parameter

The PS was categorized based on the ASA-PS [7]. The PNI is a nutritional indicator calculated using the formula (10 × albumin) + (0.005 × total lymphocytes) [8]. cT, cN, and cM stages were classified according to the eighth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control.

Postoperative complications were evaluated as the endpoint and classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [9], which categorizes surgical complications from grades I to V based on the invasiveness of the necessary treatment. Grade I entails no treatment or wound infection at the bedside; grade II entails medical therapy; grade IIIa entails surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention, but not general anesthesia; grade IIIb entails general anesthesia; grade IV entails life-threatening complications that require intensive care; and grade V entails patient death. We retrospectively reviewed the patient records to determine the incidence of complications during hospitalization and within 30 days of surgery. Serious complications were defined as those of grade ≥ IIIa. Mortality (grade V) was defined as in-hospital postoperative mortality from any cause. Postoperative AL, a major complication of rectal resection, was also evaluated, regardless of the Clavien-Dindo grade.

Statistical analyses

The inverse probability of the treatment weighting method was used to adjust for baseline differences between the lap and robot groups, and the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method was used. A multivariate logistic regression model based on the age, sex, BMI, ASA-PS, DM, PNI, LPL dissection, tumor size, cT and cN factors, diverting stoma, and preoperative treatment was used to estimate the propensity score of each patient. The missing values for all explanatory variables were imputed using a multiple imputation method, generating five sets of imputed datasets based on the aregImpute (www.rdocumentation.org/packages/Hmisc/versions/4.4-2/topics/aregImpute). The coefficients of the logistic regression model obtained from all five datasets were pooled using Rubin’s rule. Patient characteristics were compared before and after weighting by the inverse of the propensity score using the standardized mean difference (SMD), and the groups were considered homogeneous for each variable when the SMD was ≤ 0.2. To determine differences in the Clavien-Dindo grade and leakage between the two groups, we used a multivariable logistic regression model with weighting of each observation using IPTW. The variance of the coefficients was estimated using the Huber-White sandwich estimator to consider data clustering by weighting.

All statistical analyses were performed with a two-sided significance level of 5% using the R software version 4.2.2 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Patient characteristics

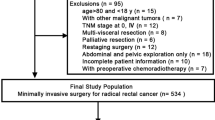

The patient selection scheme is illustrated in Fig. 1. In total, 324 rectal tumors were resected laparoscopically or with robot assistance between 2017 and 2021. Of these patients, 273 who had undergone anastomosis were retrospectively analyzed. The total patient background and oncological factors are shown in Table 1, and perioperative factors are shown in Table 2. A total of 67% were male, and the median age was 67 years old. Among these, 10% underwent preoperative treatment with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and/or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Regarding the surgical approach, 169 patients (62%) underwent the laparoscopic approach, and 104 (38%) underwent the robot-assisted approach. Diverting stomas were created in 122 (45%) patients. Postoperative complications were Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ II in 70 patients (26%) and grade ≥ III in 25 (9%). AL occurred in 16 (5.9%) patients, and urinary dysfunction occurred in 18 (6.6%).

Postoperative complications

Details of postoperative complications are shown in Table 3. The most frequent postoperative complication was urinary infection/dysfunction (18 cases), followed by AL (16 cases), abdominal infection (12 cases), ileus (12 cases), and surgical site infection (9 cases). Urinary infection/dysfunction, anastomotic leakage, and ileus were higher in the Lap group than in the Robot group. As all urinary infections were caused by urinary dysfunction, all 18 cases were analyzed as having urinary dysfunction.

Association between the surgical approach and the short-term outcomes

Comparison of the Lap and Robot groups revealed significant differences in intraoperative blood loss, tumor size, preoperative T and N stages, and the number of lymph nodes dissected (P < 0.001, P = 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.0025, and P = 0.005, respectively). Regarding postoperative complications in the Lap and Robot groups, Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ II was observed in 49 (29.0%) vs. 20 cases (19.2%), grade ≥ III in 18 (10.7%) vs. 6 cases (5.8%), AL (all grades) in 11 (6.5%) vs. 5 cases (4.8%), and urinary dysfunction (all grades) in 14 (12.1%) and 4 cases (3.8%) (Table 2).

The IPTW method revealed no marked difference between the groups with SMD ≤ 0.2 for all variables (Table 4). Although the rates of AL did not differ significantly between groups (odds ratio [OR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval CI 0.46–1.27, p = 0.296), postoperative complications of grade ≥ II (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.87, p = 0.004), and grade ≥ III (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.16–0.53, p < 0.001) were significantly less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group, the difference was more remarkable in terms of complications of grade ≥ III. As for urinary dysfunction, although there was no significant difference between the groups, it tended to be less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38–1.00; p = 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study found that robot-assisted surgery significantly reduced postoperative complications compared with laparoscopic surgery. In particular, urinary dysfunction, which is one of the most frequent postoperative complications, tended to less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group. The novelty of this study lies in its focus on anastomotic leakage and urinary dysfunction, which are clinically important morbidities. Furthermore, this result has a statistical impact when the IPTW method is used to remove various patient background biases.

Although a few studies have demonstrated the safety of robot-assisted surgery for rectal cancer, no strong evidence supports its superiority. Many randomized trials and meta-analyses have reported that robot-assisted surgery is superior to laparoscopy and associated with a significantly lower rate of conversion to laparotomy. Conversely, many reports have identified no significant differences in intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complications, or postoperative hospital stay, whereas some studies have reported inferior outcomes, such as a prolonged operation time [6, 10,11,12,13,14,15]. In the 2017 ROLARR trial, Jayne et al. conducted a large multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the short-term results of robot-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer, determining the superiority of robot-assisted surgery over laparoscopic surgery in terms of perioperative outcomes [16], but only in a limited subgroup of obese or male patients. Recently, Feng et al. conducted a large multicenter RCT of more than 1000 patients in 2022. That study reported that the patients in the robotic group had fewer postoperative complications than those in the laparoscopic group (p = 0.003) [17]. However, few reports have examined the complications in detail, including large-scale clinical trials.

Techniques and instruments for rectal cancer surgery have undergone major changes in recent years, and endoscopic and robot-assisted surgeries have become widely available. At our institution, since the number of qualified surgeons for endoscopic and robotic surgery has increased over the past five years and surgical procedures have become standardized, comparing data older than five years might have revealed a large bias. Therefore, we deemed a comparison within the most recent five-year period appropriate for analysis.

In this study, using the IPTW method, robot-assisted surgery resulted in significantly fewer postoperative complications of Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ II and ≥ III than those associated with laparoscopic surgery. Furthermore, we examined the major postoperative complications in detail. Although we observed a trend toward lower rates of AL robot-assisted surgery than in laparoscopic surgery, the difference was not significant. Regarding urinary dysfunction, although there was no statistically significant difference between the groups, the rate tended to be even lower than AL in the Robot group. Urinary dysfunction and infection were the most common postoperative complications in our study, being found in 18 cases, suggesting that robot-assisted surgery was significantly associated with a lower rate of these complications than laparoscopic surgery.

Preoperative treatment, especially neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy (NACRT), is a risk factor for pelvic dysfunction, such as urinary dysfunction, after rectal cancer surgery [18, 19]. Therefore, a sub-analysis excluding the 12 patients with NACRT in this study was conducted, and postoperative complications of urinary dysfunction (OR, 0.54; 95% CI 0.33–0.90; p = 0.02) were found to be significantly less frequent in the Robot group than in the Lap group (Supp. Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). These results indicate that the robotic approach does indeed contribute to the prevention of urinary dysfunction.

In rectal cancer resection, the urological function must be preserved even while complete tumor resection is pursued. Postoperative urinary dysfunction is often caused by intraoperative injury to the pelvic visceral nerves or pelvic plexus. Robot-assisted surgery has a more stable high-resolution field of view and multi-joint capability than laparoscopic surgery and enables accurate visualization of the anatomy and a safe approach, which can help preserve the pelvic nerves [20]. Most reports of urogenital dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery used the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and/or the International Index of Erectile Function Scores (IIEF-5), and many have reported that both the IPSS and IIEF-5 are better in robot-assisted surgery than in laparoscopic surgery [21,22,23,24,25]. Tang et al. reported a significantly faster recovery rate for urinary dysfunction with robot-assisted surgery than with laparoscopic surgery [26].

In the present study, although robot-assisted surgery was associated with a lower incidence of AL than laparoscopic surgery, the incidence was also low in the Lap group (6.5%), suggesting that patient background, improvements and innovations in anastomotic devices, and evaluation of anastomotic blood flow might have contributed more to the improvement than the surgical approach itself. For anastomotic devices, there is some concern that the number of staples used for anastomosis increases the number of small defects between staple lines, which may cause AL. Furthermore, Kim et al. reported in their prospective study that the use of two or more staples in anastomosis was associated with AL, and Fukada et al. reported that the number of staples used for anastomosis was significantly higher in male patients than in females, in procedures performed close to the anal verge than in other procedures, and in patients with a longer operative time than in those with a shorter time [27, 28].

Recently, indocyanine green fluorescence angiography (ICG-FA) has been widely used in colorectal surgery to evaluate the blood flow at anastomotic sites. ICG-FA is a near-infrared fluorescent dye that can be detected by imaging systems. It can be used to detect areas of vascular failure and, if necessary, accurately perform anastomoses in areas with a good blood flow. Some reports have demonstrated the usefulness of ICG-FA in preventing AL during colorectal surgery [29].

Robot-assisted rectal cancer surgery has only been performed for a relatively short period of time thus far, and few studies have reported the long-term outcomes [30]. Various randomized trials and meta-analyses have reported significantly lower circumferential resection margin (CRM) positive rates in robot-assisted surgery than laparoscopic surgery [10, 11], but many others have reported no significant differences in the long-term outcomes [12, 14]. Therefore, the results remain controversial. Establishing the superiority of robot-assisted rectal cancer surgery over laparoscopic surgery in terms of the long-term outcomes will require large-scale randomized controlled trials, such as the ongoing ROLARR or COLRAR trials. Postoperative complications, especially intra-abdominal infections, such as AL, are often reported to be poor long-term prognostic factors. In a meta-analysis, Wang et al. reported that the occurrence of postoperative AL significantly increased the local recurrence rate and was a poor prognostic factor for both the overall and cancer-specific survival [31]. The results suggest that reducing postoperative complications, as in this study, may contribute to prolonging the long-term prognosis.

In addition, in the present study, the number of lymph nodes collected was significantly lower in the Robot group than in the Lap group. One reason for this may be that there was a significant difference in tumor progression between the two groups, which led to a difference in the level of dissection. Second, in Japan, the mesorectal ligament around the tumor is peeled off from the resected specimen, and the lymph nodes are collected. In recent years, to evaluate CRM, the mesentery near the tumor is fixed in formalin without being removed, and in the end, pathologists often count the number of lymph nodes. Having multiple parties handle the resected specimens during our study may have affected the results.

Although this was a single-center study, the surgeons were all certified by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery, a medical advisor always served as the primary surgeon or the first assistant, and the entire team was made up of surgeons who had attended designated training certification sessions. Furthermore, the patients’ background characteristics, oncological factors, and surgical factors, including the surgical equipment used, might have resulted in some biases; however, we believe that such biases were minimized between the two groups due to the implementation of the IPTW method.

One major limitation of this study was that it was not a prospective, randomized study. With the rapid spread of robotic devices, especially in high-volume center hospitals, most rectal tumor surgeries are now performed using robot-assisted approaches; therefore, it is difficult to conduct multicenter randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

We identified better short-term outcomes after robot-assisted surgery for rectal tumors than with laparoscopic surgery, suggesting that it is safer than laparoscopic surgery.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

- LPL:

-

Lateral pelvic lymph node

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PS:

-

Physical status

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- PNI:

-

Prognostic nutritional index

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- AL:

-

Anastomotic leakage

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- ICG-FA:

-

Indocyanine green-fluorescence angiography

- IPSS:

-

International prostate symptom score

- IIEF-5:

-

International index of erectile function score

- NAC:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- NACRT:

-

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

- CRM:

-

Circumferential resection margin

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection of Stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1346–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10529.

Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALaCaRT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1356–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12009.

Weber PA, Merola S, Wasielewski A, Ballantyne GH. Telerobotic-assisted laparoscopic right and sigmoid colectomies for benign disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1689–94.

Pigazzi A, Ellenhorn JD, Ballantyne GH, Paz IB. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1521–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-005-0855-5.

Wang X, Cao G, Mao W, Lao W, He C. Robot-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2020;16:979–89. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_533_18.

Abouleish AE, Leib ML, Cohen NH. ASA provides examples to each ASA physical status class. Asa Monit. 2015;79:38–9.

Buzby GP, Mullen JL, Matthews DC, Hobbs CL, Rosato EF. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. Am J Surg. 1980;139:160–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(80)90246-9.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae.

Xiong B, Ma L, Huang W, Zhao Q, Cheng Y, Liu J. Robotic versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of eight studies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:516–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2697-8.

Sun Y, Xu H, Li Z, Han J, Song W, Wang J, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0816-6.

Liao G, Li YB, Zhao Z, Li X, Deng H, Li G. Robotic-assisted surgery versus open surgery in the treatment of rectal cancer: the current evidence. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26981. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26981.

Cui Y, Li C, Xu Z, Wang Y, Sun Y, Xu H, et al. Robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic operation in anus-preserving rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1247–57. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S142758.

Li X, Wang T, Yao L, Hu L, Jin P, Guo T, et al. The safety and effectiveness of robot-assisted versus laparoscopic TME in patients with rectal cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. 2017;96: e7585. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007585.

Prete FP, Pezzolla A, Prete F, Testini M, Marzaioli R, Patriti A, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2018;267:1034–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002523.

Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H, Croft J, Corrigan N, Copeland J, et al. Effect of robotic-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic surgery on risk of conversion to open laparotomy among patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer: The ROLARR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1569–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7219.

Feng Q, Yuan W, Li T, Tang B, Jia B, Zhou Y, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for middle and low rectal cancer (REAL): short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:991–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00248-5.

Huang M, Lin J, Yu X, Chen S, Kang L, Deng Y, et al. Erectile and urinary function in men with rectal cancer treated by neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone: a randomized trial report. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1349–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-016-2605-7.

Li X, Fu R, Ni H, Du N, Wei M, Zhang M, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant therapy on the functional outcome of patients with rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oncol. 2023;35:e121–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2022.07.003.

Luca F, Valvo M, Ghezzi TL, Zuccaro M, Cenciarelli S, Trovato C, et al. Impact of robotic surgery on sexual and urinary functions after fully robotic nerve-sparing total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2013;257:672–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318269d03b.

D’Annibale A, Pernazza G, Monsellato I, Pende V, Lucandri G, Mazzocchi P, Alfano G, et al. 2013 Total mesorectal excision: a comparison of oncological and functional outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 1887;27:95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2731-4.

Broholm M, Pommergaard HC, Gögenür I. Possible benefits of robot-assisted rectal cancer surgery regarding urological and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:375–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12872.

Lee SH, Lim S, Kim JH, Lee KY. Robotic versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;89:190–201. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2015.89.4.190.

Wang G, Wang Z, Jiang Z, Liu J, Zhao J, Li J. Male urinary and sexual function after robotic pelvic autonomic nerve-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13: e1725. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.1725.

Kim HJ, Choi GS, Park JS, Park SY, Yang CS, Lee HJ. The impact of robotic surgery on quality of life, urinary and sexual function following total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis with laparoscopic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:O103–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14051.

Tang B, Gao G, Ye S, Liu D, Jiang Q, Ai J, et al. Male urogenital function after robot-assisted and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a prospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01592-1.

Kim JS, Cho SY, Min BS, Kim NK. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis with a double stapling technique. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:694–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.021.

Fukada M, Matsuhashi N, Takahashi T, Imai H, Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. Risk and early predictive factors of anastomotic leakage in laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1716-3.

Blanco-Colino R, Espin-Basany E. Intraoperative use of ICG fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta–analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1731-8.

Kim J, Baek SJ, Kang DW, Roh YE, Lee JW, Kwak HD, et al. Robotic resection is a good prognostic factor in rectal cancer compared with laparoscopic resection: long-term survival analysis using propensity score matching. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:266–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000770.

Wang S, Liu J, Wang S, Zhao H, Ge S, Wang W. Adverse effects of anastomotic leakage on local recurrence and survival after curative anterior resection for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2017;41:277–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3761-1.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JYT and NM collected clinical data and drafted the manuscript. JYT, NM, RY, SK, and TT assisted with the patient management. JYT, NM, RY, SK, TT, HH, TH, and FK collected clinical data. NM revised and supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

Nobuhisa Matsuhashi received honoraria for writing promotional material for AMCO Inc. and Johnson & Johnson. Nobuhisa Matsuhashi received a research grant from Covidien Japan, and all other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Central Ethics Committee of Gifu University (Approval Number: 2019–147).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

595_2023_2758_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 16 KB) Table 1. Patients’ background characteristics and oncological factors after excluding NACRT cases. *Mean ± SD, **Clavien-Dindo grade, †Pearson's chi-squared test. SD: standard deviation, BMI: body mass index, ASA-PS: American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status, DM: diabetes mellitus, PNI: prognostic nutritional index = (10 × Alb) + (0.005 × TLC), AD: adenocarcinoma, NET: neuroendocrine tumor, AV: anal verge, NAC: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, NACRT: neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

595_2023_2758_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Supplementary file2 (DOCX 15 KB) Table 2. Perioperative factors after excluding NACRT cases. *Mean ± SD, **Clavien-Dindo grade, †Pearson's chi-squared test. SD: standard deviation, LPL: lateral pelvic lymph node, AL: anastomotic leakage, UD: urinary dysfunction

595_2023_2758_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Supplementary file3 (DOCX 17 KB) Table 3. Patients’ background characteristics and oncological factors before and after IPTW after excluding NACRT cases. * Mean ± SD. NACRT: neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weighting, SMD: standardized mean difference, SD: standard deviation, BMI: body mass index, ASA-PS: American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status, DM: diabetes mellitus, PNI: prognostic nutritional index = (10 × Alb) + (0.005 × TLC), LPL: lateral pelvic lymph node

595_2023_2758_MOESM4_ESM.docx

Supplementary file4 (DOCX 13 KB) Table 4. Risk of postoperative urinary dysfunction in the Robot group vs. the Lap group after IPTW after excluding NACRT cases. †Pearson's chi-squared test. NACRT: neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weighting, CI: confidence interval

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tajima, J.Y., Yokoi, R., Kiyama, S. et al. Technical outcomes of robotic-assisted surgery versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal tumors: a single-center safety and feasibility study. Surg Today 54, 478–486 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-023-02758-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-023-02758-x