Abstract

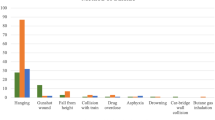

Although child mortality is decreasing in Sweden, an increase in suicide rates has been previously observed among children and adolescents collectively. To increase knowledge about trends, demographics, and means in child suicides, data including all child (< 18 years) suicides in Sweden in 2000 through 2018 were retrieved from the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine. In all, a total of 416 child suicides were found in a 19-year period, accounting for an annual suicide rate of 1.1/100,000 child population. The number of suicides increased with 2.2% by each successive year during the study period (p < 0.001). The mean age in both sexes was 16 years; boys accounted for 55% and girls for 45% of all study cases. The majority of the children who died by suicide (96%) were teenagers (13–17 years old) and suicides in children younger than 10 years were uncommon. Suicide methods were 59% hanging, 20% lying/jumping in front of a moving object, 8% jumping from a height, 7% firearm injury, 4% poisoning, and 2% other methods. Sex differences were significant (p < 0.001) only for firearms being preferably used by boys. The vast majority of firearms used were licensed long-barreled weapons.

Conclusion: The number of child suicides in Sweden is relatively low but increasing. Most of the children used a violent and highly lethal method. Prevention of premature mortality is an urgent concern with an emphasis on resolutely reducing the availability of suicide means.

What is Known: • Suicide is a significant cause of death globally among children, bringing tragic consequences for young individuals, their family, and the entire society. • Suicide rates and distribution of suicide methods in children differ between countries and settings, but studies of time trends are scarce. | |

What is New: • Increasing number of minors’ suicides and the predominance of violent methods emphasize the importance of prevention strategies tailored for a child population. • Even in a setting of very restrictive firearm laws, firearm suicides in children must not be overlooked. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, suicides represent a significant health problem as the leading cause of death among 10–19-year-olds in low- and middle-income countries and the second leading cause of death in high-income countries in the European Region [1]. The rate of child suicides and its reporting varies between countries [2]. In the 5-year period (2014–2018), the suicide rate among 15–19-year-olds in Sweden (6.9 per 100,000 people aged 15–19 years) was higher than in Denmark (3.7) and Germany (4.7), but lower than in Finland (8.6) [3]. Among European countries, the highest rates for the same age group and period were reported in Estonia (13.3) and Iceland (17.0), while Greece had the lowest rate of 1.5 [3].

According to the WHO, depression and anxiety disorders are among the top five causes of overall disease burden in children and adolescents in the WHO European Region [1]. Furthermore, mental health issues in Swedish children and youths have increased in recent decades [4], as have suicide attempts and suicides among 15–24 year-olds [5]. The Public Health Agency of Sweden reported psychosomatic disorders, performance anxiety related to school, and differences in the socioeconomic background as factors contributing to increasing mental health problems in youth [4].

Previous studies of suicide rate trends and suicide methods in all child (< 18 years) suicides are scarce [6,7,8,9] and lacking from Sweden. Commonly, limited age groups of minors [2, 10] or ages including late adolescence (18–19 years) [1, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17] and young adults (22–24 years) [18] have been investigated, but suicides in younger children (< 15 years) were presented only sporadically in official national reports [5].

The present nationwide study of child suicides explores the suicide rate and demographic factors of age and sex in a 19-year-long period (2000–2018). Finally, the study aims to offer evidence and knowledge about child suicide methods and to inform child suicide prevention strategies.

Materials and methods

Data were retrieved from the database of the National Board of Forensic Medicine regarding all registered suicides in children (under 18 years of age) in Sweden from 2000 through 2018. The database contains information from the police reports (circumstances) and the medicolegal autopsy (autopsy and toxicological findings, cause, and manner of death). In all, 416 child suicides were found and these data are included in the present study.

Variables collected were age, sex, date and place of death, presence of suicide note, information about survivability, and cause of death. Data was presented in two age groups (< 13 years and 13–17 years). The Swedish national guidelines for youth health and development define teenage starting at 13 years with age-specific developmental and health issues [19], hence why the cutoff age in the age groups was set at 13 years. In cases where firearm injury was the cause of death, information if the child was licensed/unlicensed firearm owner (yes/no), if the firearm involved was licensed (yes/no) and stored in the safety locker (yes/no), was received via the Swedish Police.

SPSS (version 26) for Windows was used in statistical data analyses. χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were applied for the comparison of frequencies (method and sex, suicide seasons). The Poisson regression model was used for the analysis of the relationship between the number of child suicides and time (years), adjusted for child population size. The goodness-of-fit test did not show under- or overdispersion in the Poisson model. Data about child population size was retrieved from Statistics Sweden, the authority responsible for official statistics in Sweden. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Mortality and demographics

In total, 416 child suicides were found in the period from 2000 through 2018. The suicide rate was, on average, 22 suicides/year or 1.1 per 100,000 child population/year (mean child population during the study period was 1.97 million). The highest rate of 2.14 child suicides per 100,000 child population was found in southeast Sweden, but also several northern counties had a high rate, > 1.5 per 100,000 child population (Fig. 1). The suicide rate increased with age (Fig. 2). The annual overall suicide rates and rates for boys and girls are illustrated in Fig. 3. The Poisson regression analysis (df = 1) showed that the time (years) was a significant and positive predictor of the number of child suicides (B = 0.021, S.E. = 0.012, p < 0.001), adjusted for child population size. The incidence rate ratio (IRR = 1.022) indicates that there was a 2.2% increase in the number of child suicides by each successive year.

The mean age was 16 years for both sexes (median 16 years, SD 1.5), 15 years for girls (median 16, SD 1.4), and 16 years for boys (median 16, SD 1.6). Boys accounted for 55% of all study cases. The majority of the children who died by suicide (96%) were teenagers (Table 1) and one-quarter (26%) were younger than 15 years.

Suicide methods and circumstances

The most common suicide methods were hanging (59%) and jumping or lying in front of a moving object (20%) (Table 1). Jumping from a height was the third (8%) and firearm suicide was the fourth most common suicide method (7%). Firearm suicide was uncommon among preteens (< 13 years) and girls. No cases of poisoning, drowning, or suffocation were found among preteens. A comparison between sexes indicated a statistically significant difference only for firearms (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Poisoning was more common among girls (65% of all poisonings), but this sex difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). Among poisonings, 88% were caused by licit drugs and 12% by carbon monoxide. One child died by burning.

The majority (94%) of the children was found dead, and the remaining minors died in hospital. In 58/416 (14%) cases, a suicide note was found. Twenty children (5%) were living in a residential care home when the suicide occurred.

Many suicides (31%) occurred in the autumn months (September–November), followed by 25% in the spring season (March–May). The summer (June–August) and winter (December-February) seasons each had equal shares of suicides (22%); both of these seasons had a significantly lower number of suicides than the autumn and spring months (χ2 = 5.538, df = 1, p = 0.019).

Firearms

Firearms were involved in 28 of the suicides; 89% (25/28) of the children had a gunshot wound to the head and 11% (3/28) to the chest. The firearm was licensed in at least 86% (24/28) of the cases; in the remaining four cases, this aspect was unknown. In 96% (27/28), the minor was not a licensed firearm owner. Almost all firearms (96%, 27/28) were long-barreled, and the firearm was kept in a safety locker in 64% of the cases (18/28), not stored in a safety locker in 4% (1/28), and unknown in the remaining cases. Firearm suicides were spread over 15 of the 21 counties. The highest share of all firearm suicides was found on the island of Gotland (33%) and in Västmanland (22%).

Discussion

This Swedish national study represents unique epidemiological research of suicide deaths in children during a 19-year-long period and offers evidence and aspects that should permeate specific prevention strategies for child suicides in a western setting.

Mortality, demographics, and seasonal variation

Reported international variations of child and adolescent suicide rates and methods [1, 2] may be explained by differences in sociodemographic, health and cultural factors, prevention efforts, and availability of suicide means. In line with global statistics, the suicide rate is lower among Swedish children than among adults [5]. Overall, child mortality is decreasing in Sweden, mostly due to the decline in transport-related and other unintentional deaths [20]. Consequently, child injury mortality patterns have changed from unintentional injury predominance to more equal shares of intentional and unintentional injury in 1999–2012 [21]. Escalation of mental health issues in youths and an increased suicide rate among 15–24-year-olds in Sweden [5] makes an increasing number of child suicides to be expected.

A higher suicide rate in the northernmost counties may reflect a higher overall suicide rate in these counties [22] but, in spite of the highest child suicide rates, Uppsala and Västerbotten counties had the lowest overall suicide rates of all counties [22]. One-third of teenage deaths in the northern counties were intentional, predominantly suicides, with the highest rates among 16–19-year-old boys and with hanging, firearm injury, and intoxication as the most common methods [11]. Moreover, an interview study emphasized the cultural and sociopolitical aspects important for teenage suicides in northern Sweden, where the majority occurred in rural and depopulated geographical areas [23].

It has been suggested that the suicide rates can be underestimated due to the classification of the manner of death as undetermined or unintentional [2]. The classification issue may be linked to a suicide-related social stigma and/or misinterpretation of the child’s maturity and understanding of death [2]. Minors’ act of ending their own life may be seen rather as a deliberate means of self-harm than a suicidal act. The annual number of deaths with an undetermined manner of death was, however, much lower (2 deaths/year) among 0–14-year-olds than among 15–19-year-olds (8 deaths/year) in 2000–2018 [24]. Although the official mortality statistics present 15–19-year-olds as one age group, underestimation of child suicides might be limited.

An increasing suicide rate with age is an expected finding [7, 16, 25, 26] and can be partly explained by increased social pressure in the upper teenage years [12] and a higher prevalence of mental health issues among older children [25, 27]. Additionally, a low suicide rate in younger children and preteens was suggested to reflect age-related cognitive limitations in understanding the concept of death [28, 29] and in practical planning of the suicide act [12]. Children are said to understand death and its concept of irreversibility, as well as the concept of suicide [29] by the age of 8–9 years; before this age, they seem to consider death as reversible [28]. Accordingly, the younger child’s maturity and capability to act should not be underestimated [29, 30].

Although male preponderance to die by suicide is expected to grow with increasing age [22, 25, 26], the share of boys in the present study was only slightly higher than that of girls. In contrast, boys accounted for 75% of child suicides [31] and 85% of firearm suicides among 10–18-year-olds in the USA [32]. Firearm availability and the fact that males tend to use more lethal suicide methods could partly explain the appearance of an earlier sex asymmetry in the USA than in, e.g., Sweden.

The share of suicides was significantly lower during the summer and winter months—when Swedish children have longer school breaks—than in the autumn and spring months. Similarly, an Austrian study presented lower suicide rates during the summer months, suggesting a possible relationship with reduced school stress [16]. However, a causal relationship cannot be concluded, and further investigations of precipitative factors in the seasonal analysis are necessary.

Suicide methods

Due to similarities in availability and lethality of the suicide means, some suicide method patterns have been described in clusters of countries [33]. Such a cluster analysis of suicide methods in 101 countries (2000–2009) and for 10–19-year-olds showed that Sweden was in the cluster with a mixture of methods, but with a predominance of hangings [33]. Hanging was a leading method also in England [34], Ireland [18], Canada [26], the USA [33], and Mexico [9]. Moreover, it was the most common method among the youngest, < 12 years of age, in the USA [10], as in the present study. Recently, an international review confirmed a high hanging prevalence ranging from 48–90% of child suicides [30].

A change in suicide method among children, from poisoning to hanging, has been explained by general trends with a decrease of CO poisoning in car exhaust fumes since cars became equipped with catalytic converters [35]. Suicides due to gas poisonings decreased in Sweden in the overall population from 1985 through 2004 and a shift from gas poisoning and drowning to hanging as a suicide method has been noticed, still with poisonings slightly more frequent than hangings [36]. Thus, increased use of hanging among children may reflect a general trend. Contrary to the small share of poisonings found in child suicides, poisoning as a “less violent” method is considerably more prevalent in adults, accounting for approximately one-third of all adult suicides [5, 36]. The small share of poisonings (4%) in the present study was in the lower interval (4–30%) of methods reported in previous studies [30, 34] that is possibly related to the change of methods and a restriction of drugs availability occurring before the study period.

Accordingly, the distribution of suicide methods among children found here does not imitate those in the general population [5]. Official national reports are masking child suicide data by age grouping together with adults, inhibiting an accurate comparison of methods between children and adults [22]. The preference to choose highly lethal methods in most of the suicides in the present study is a worrying fact. These methods together with firearms are more attributed to impulsiveness compared to other methods [37]. The impulsive attributes in suicide attempts and poor coping with stress seem also to be more common in children [30].

As reported in an older Swedish study, boys used violent methods (hanging, jumping, and firearms) more often than girls, but a change from non-violent to violent methods was observed for girls in the 1980s [17]. The share of violent methods among girls (91%) found here is higher than 36% found in the 1980s (among < 19-year-olds) [17]. Violent methods were used more often than non-violent methods by both sexes in the present study.

Firearms

Internationally, firearm usage was the second most common method among children < 14 years old [30], but only the fourth most common method in the present material, particularly used by older children. In the USA, firearm suicides accounted for almost half of all suicides among 10–19 years old in 2017 [31] and safe firearm storage was suggested as a prevention measure [32]. Differences in firearm availability may explain such variations between countries. Swedish firearm legislation is very restrictive, limiting firearm licenses to persons > 18 years of age and requiring mandatory firearm storage in safety lockers [38]. Firearms can, only in exceptional circumstances, be licensed to individuals < 18 years, and a lower annual number of suicides due to firearms (1.5) among children than among Swedish adults (⁓ 100) [39] is thus expected.

Firearms are preferred by males as a suicide means both by adults [39] and children in the present study. In Sweden, licensed firearm owners are mostly male and are hunters [39, 40] and it is common that children follow their family in the hunt [41]. Research has shown that household availability and familiarity with firearms are important risk factors for suicides among youths in the USA [42, 43] and Australia [44]. Minors’ choice of the firearm as a method can be related to the availability of, and familiarity with, firearms also in a European setting.

In the USA, handguns accounted for two-thirds of firearms in child suicides and were mostly kept unlocked [32]. In contrast, the majority of firearms in the present study was long-barreled and stored in safety lockers, reflecting the dominance of rifles and shotguns for hunting and target shooting among Swedish gun owners [40], the strict licensing of handguns, and the strict storage regulation [38]. In spite of these storage restrictions, 28 children died from self-inflicted intentional firearm injuries in the study period. Most firearms were licensed, as in unintentional firearm deaths among Swedish children [45]. In conclusion, although stored in a locker, guns at home are associated with a higher risk of firearm suicide [42], and the locker’s keys or code must be kept unavailable.

Strengths and limitations

A longitudinal design and analysis of accurate national data represent the strengths of the present study. Furthermore, additional sources from the police authority were used for information about firearms involved in child suicides. According to Swedish laws and regulations, all unnatural deaths should undergo a medicolegal autopsy at the National Board of Forensic Medicine. Missing cases among suicides are few (internal data). The data are thus representative of child suicides in Sweden during the study period. The register data offers a good consistency in examined variables. However, a limitation of the retrospective study design is the non-consistency of information regarding firearm storage.

Prevention

Prevention of child suicides is a challenging task including multiple aspects. Besides universal prevention strategies such as restriction of means, efforts should reflect age-specific issues and should be adopted to specific local conditions. Restriction of suicide means at railways, bridges, and firearms must be targeted, representing common prevention means for both children and adults. Hanging as a dominant means of suicide is challenging to prevent due to its wide availability and increasing societal acceptance [14, 33]. Yet, prevention can include, e.g., improved primary prevention, mitigating the risk factors for suicide, and interventions affecting broader general conditions and risk groups among children.

Precipitating factors differ between children and adults and may be related to school problems such as bullying [46,47,48], underachievement, disturbances in relation with parents, and/or family violence [30]. In the present study, 5% of the children who died by suicide had been placed in a residential foster home. Children who are adopted [49,50,51] or living in a care home [52] are also at a higher suicide risk than others. As for adults [53], previous suicide attempts, psychiatric disorders, and traumatic events are some of the risk factors [30, 54]. High-quality psychiatric health care for children, prevention programs at school, and strengthening of family relations [55] are evidently important prevention strategies.

Conclusions

Child suicide prevention represents an important national priority, and the mortality trend needs to be inverted. Further research is necessary to enlighten apparent regional differences in child suicide rates. Official mortality statistics should be improved for surveillance of suicide trends regarding minors separately from suicide trends for older ages. Risk and vulnerability factors and prevalence of suicide methods differ from those in adults; hence, protective strategies need to be tailored explicitly for the child population and for the choice towards more lethal means.

Availability of data and material

Data and material are available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization (2018) Adolescent mental health in the European Region. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/383891/adolescent-mh-fs-eng.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021

Kõlves K, De Leo D (2014) Suicide rates in children aged 10–14 years worldwide: changes in the past two decades. Br J Psychiatry 205:283–285. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144402

European commission, Eurostat (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database. Accessed 9 May 2021

Public Health Agency of Sweden (2019) The reasons for increase mental health issues in youth [Därför ökar psykisk ohälsa bland unga]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/psykisk-halsa-och-suicidprevention/barn-och-unga--psykisk-halsa/darfor-okar-psykisk-ohalsa-bland-unga/. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of Mental Ill-Health (2021) Suicide in Sweden [Självmord i Sverige]. https://ki.se/nasp/sjalvmord-i-sverige. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Lahti A, Harju A, Hakko H, Riala K, Räsänen P (2014) Suicide in children and young adolescents: a 25-year database on suicides from Northern Finland. J Psychiatr Res 58:123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.020

Oprescu F, Scott-Parker B, Dayton J (2017) An analysis of child deaths by suicide in Queensland Australia, 2004–2012. What are we missing from a preventative health services perspective? J Inj Violence Res 9:75–82. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v9i2.837

Mendes R, Santos S, Taveira F, Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Santos A, Magalhães T (2015) Child suicide in the north of Portugal. J Forensic Sci 60:471–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12685

Aguilar-Velázquez DG, González-Castro TB, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Juárez-Rojop E, I, López-Narváez ML, Ana Frésan, Hernández-Díaz Y, Guzmán-Priego CG, (2017) Gender differences of suicides in children and adolescents: analysis of 167 suicides in a Mexican population from 2003 to 2013. Psychiatry Res 258:83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.083

Bridge JA, Asti L, Horowitz LM, Greenhouse JB, Fontanella CA, Sheftall AH, Kelleher KJ, Campo JV (2015) Suicide trends among elementary school-aged children in the United States from 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr 169:673–677. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0465

Johansson L, Stenlund H, Lindqvist P, Eriksson A (2005) A survey of teenager unnatural deaths in northern Sweden 1981–2000. Accid Anal Prev 37:253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2004.09.002

McClure GM (2001) Suicide in children and adolescents in England and Wales 1970–1998. Br J Psychiatry 178:469–474. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.5.469

Schmidt P, Müller R, Dettmeyer R, Madea B (2002) Suicide in children, adolescents and young adults. Forensic Sci Int 127:161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00095-6

Shaw D, Fernandes JR, Rao C (2005) Suicide in children and adolescents: a 10-year retrospective review. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 26:309–315. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.paf.0000188169.41158.58

Skinner R, McFaull S (2012) Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980–2008. CMAJ 184:1029–1034. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.111867

Dervic K, Friedrich E, Prosquill D, Kapusta ND, Lenz G, Sonneck G, Friedrich MH (2006) Suicide among Viennese minors, 1946–2002. Wien Klin Wochenschr 118:152–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-006-0567-4

Hultén A, Wasserman D (1992) Suicide among young people aged 10–29 in Sweden. Scand J Soc Med 20:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494

Arensman E, Bennardi M, Larkin C, Wall A, McAuliffe C, McCarthy J, Williamson E, Perry IJ (2016) Suicide among young people and adults in Ireland: method characteristics, toxicological analysis and substance abuse histories compared. PLoS One 11(11):e0166881. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166881.89202000201

1177 Vårdguiden (2019) Teenagers 13–18 years [Tonåringar 13–18 år]. https://www.1177.se/Skane/barn--gravid/sa-vaxer-och-utvecklas-barn/barnets-utveckling/tonaringar-13-18-ar/#:~:text=I%20ton%C3%A5ren%20g%C3%A5r%20man%20fr%C3%A5n,och%20hur%20de%20vill%20vara. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Jansson B, De Leon AP, Ahmed N, Jansson V (2006) Why does Sweden have the lowest childhood injury mortality in the world? The roles of architecture and public pre-school services. J Public Health Policy 27:146–165. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200076

Bäckström D, Steinvall I, Sjöberg F (2017) Change in child mortality patterns after injuries in Sweden: a nationwide 14-year study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 43:343–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-016-0660-y

Public Health Agency of Sweden (2021) Suicide mortality [Dödlighet i suicid]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/tolkad-rapportering/folkhalsans-utveckling/resultat/halsa/suicid-sjalvmord/#:~:text=Suicidtalet%20bland%20personer%2015%20%C3%A5r,Gotlands%20l%C3%A4n%20(figur%205). Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Lindqvist P, Johansson L (2000) Teenage suicides in northern Sweden: an interview study of investigating police officers. Inj Prev 6:115–119. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.6.2.115

Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2021) Cause of death database [Statistikdatabas för dödsorsaker]. https://sdb.socialstyrelsen.se/if_dor/val.aspx. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Soole R, Kõlves K, De Leo D (2015) Suicide in children: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res 19:285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2014.996694

Rhodes AE, Khan S, Boyle MH, Wekerle C, Goodman D, Tonmyr L, Bethell J, Leslie B, Manion I (2012) Sex differences in suicides among children and youth: the potential impact of misclassification. Can J Public Health 103:213–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403815

Grøholt B, Ekeberg O, Wichstrøm L, Haldorsen T (1997) Youth suicide in Norway, 1990–1992: a comparison between children and adolescents completing suicide and age- and gender-matched controls. Suicide Life Threat Behav 27:250–263

Cuddy-Casey M, Orvaschel H (1997) Children’s understanding of death in relation to child suicidality and homicidality. Clin Psychol Rev 17:33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00044-x

Mishara BL (1999) Conceptions of death and suicide in children ages 6–12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav 29:105–118

Sousa GS, Santos MSPD, Silva ATPD, Perrelli JGA, Sougey EB (2017) Suicide in childhood: a literatura review. Cien Saude Colet 22:3099–3110. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017229.14582017

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Violent Death Reporting System. https://wisqars.cdc.gov:8443/nvdrs/nvdrsDisplay.jsp. Accessed 9 May 2021

Schnitzer PG, Dykstra HK, Trigylidas TE, Lichenstein R (2019) Firearm suicide among youth in the United States, 2004–2015. J Behav Med 42:584–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00037-0

Kõlves K, De Leo D (2017) Suicide methods in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26:155–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0865-y

Zainum K, Cohen M (2017) Suicide patterns in children and adolescents: a review from a pediatric institution in England. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 13:115–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-017-9860-y

McClure GM (2000) Changes in suicide in England and Wales, 1960–1997. Br J Psychiatry 176:64–67. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.1.64

National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of Mental Ill-Health (2007) Suicide statistics 1980–2004 and suicide attempts statistics 1987–2004 in Sweden and Stockholm county [Statistik över självmord 1980–2004 och självmordsförsök 1987–2004 county i Sverige och Stockholms län]. https://ki.se/sites/default/files/migrate/statistikrapport_2007_gallande_19802004.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Dumais A, Lesage AD, Lalovic A, Seguin M, Tousignant M, Chawky N, Turecki G (2005) Is violent method of suicide a behavioral marker of lifetime aggression? Am J Psychiatry 162:18. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1375

Firearms Act of (1996) SFS 1996:67 [Vapenlag 1996, SFS 1996:67]. http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/vapenlag-199667_sfs-1996-67. Accessed 9 May 2021 (In Swedish)

Junuzovic M, Rietz A, Jakobsson U, Midlöv P, Eriksson A (2019) Firearm deaths in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 29:351–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky137

Swedish Police (2006) Report Firearm regulation etc. [Vapenlagstiftningen m.m.] (in Swedish)

Junuzovic M, Midlöv P, Lönn SL, Eriksson A (2013) Swedish hunters’ safety behaviour and experience of firearm incidents. Accid Anal Prev 18:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2013.08.002

Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP (1991) The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides. A case-control study JAMA 266:2989–2995

Hemenway D (2011) Risks and benefits of a gun in the home. Am J Lifestyle Med 5:502–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827610396294

Klieve H, Sveticic J, De Leo D (2009) Who uses firearms as a means of suicide? A population study exploring firearm accessibility and method choice. BMC Med 7:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-7-52

Junuzovic M, Sjöberg A, Eriksson A (2016) Unintentional nonhunting firearm deaths in Sweden, 1983–2012. J Forensic Sci 61:966–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13098

Van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J (2014) Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 168:435–442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143

Hinduja S, Patchin JW (2010) Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res 14:206–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2010.494133

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Roumeliotis P, Xu H (2014) Associations between cyberbullying and school bullying victimization and suicidal ideation, plans and attempts among Canadian schoolchildren. PLoS One 9:e102145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102145

Hjern A, Allebeck P (2002) Suicide in first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden: a comparative study. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol 37:423–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0564-5

Keyes MA, Malone SM, Sharma A, Iacono WG, McGue M (2013) Risk of suicide attempt in adopted and nonadopted offspring. Pediatrics 132:639–646. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3251

Von Borczyskowski A, Hjern A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B (2006) Suicidal behaviour in national and international adult adoptees: a Swedish cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0974-2

Evans R, White J, Turley R, Slater T, Morgan H, Strange H, Scourfield J (2017) Comparison of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide in children and young people in care and non-care populations: systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Child Youth Serv Rev 82:122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.020

World Health Organisation (2019) Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide. Accessed 9 May 2021

Dodig-Curković K, Curković M, Radić J, Degmecić D, Fileković P (2010) Suicidal behavior and suicide among children and adolescents-risk factors and epidemiological characteristics. Coll Antropol 34:771–777

Siu AMH (2019) Self-harm and suicide among children and adolescents in Hong Kong: a review of prevalence, risk factors, and prevention strategies. J Adolesc Health 64:59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.004

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Patrick Reilly for his help in manuscript editing.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J. conceived the idea, developed the method, applied for register data, analyzed data, performed some of the statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. K.T. analyzed data under M.J.’s supervision. U.J. performed statistical analyses (Poisson regression, Table 1) and made Figs. 2 and 3. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This retrospective research study involves registered data about decedents and not living persons. Ethical approval is not required according to the Swedish Ethical Review Act (SFS 2003:460). Register data retrieval for research purposes was approved by the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine (Dnr X19-90291).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Paolo Milani

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Junuzovic, M., Lind, K.M.T. & Jakobsson, U. Child suicides in Sweden, 2000–2018. Eur J Pediatr 181, 599–607 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04240-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04240-7