Abstract

To date, the lichens Chrysothrix candelaris and Varicellaria hemisphaerica have been classified as accurate primeval lowland forest indicators. Both inhabit particularly valuable remnants of oak-hornbeam forests in Europe, but tend toward a specific kind of vicariance on a local scale. The present study was undertaken to determine habitat factors responsible for this phenomenon and verify the indicative and conservation value of these lichens. The main spatial and climatic parameters that, along with forest structure, potentially affect their distribution patterns and abundance were analysed in four complexes with typical oak-hornbeam stands in NE Poland. Fifty plots of 400 m2 each were chosen for detailed examination of stand structure and epiphytic lichens directly associated with the indicators. The study showed that the localities of the two species barely overlap within the same forest community in a relatively small geographical area. The occurrence of Chrysothrix candelaris depends basically only on microhabitat space provided by old oaks and its role as an indicator of the ecological continuity of habitat is limited. Varicellaria hemisphaerica is not tree specific but a sufficiently high moisture of habitat is essential for the species and it requires forests with high proportion of deciduous trees in a wide landscape scale. Local landscape-level habitat continuity is more important for this species than the current age of forest stand. Regardless of the indicative value, localities of both lichens within oak-hornbeam forests deserve the special protection status since they form unique assemblages of exclusive epiphytes, including those with high conservation value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The spared remnants of natural deciduous or mixed forests in Europe represent a typical zonal formation constituting the dominant type of potential vegetation over large areas of the continent (Ellenberg 1988). Contrary to commercial forests, used primarily as a source of wood, deciduous forests have high environmental value, as they are characterised by great diversity of tree species and constitute important refuges for various organisms (Faliński and Mułenko 1995; Barbier et al. 2008).

Lichens are a conspicuous component, occupying the entire space of forest communities (Coxson and Nadkarni 1995; Sillett and Antoine 2004; Seaward 2008; Ellis 2012). While they occur in various ecological groups, epiphytes clearly dominate in deciduous and mixed forests of the temperate zone. Many lichens are closely related to a specific habitat and thus may possess indicative value (e.g., Nimis and Martellos 2001). Both external and internal factors, e.g., climate, landscape form, composition and maturity of trees, and biological interactions (Leppik and Jüriado 2008; Moning et al. 2009; Marini et al. 2011; Hauck et al. 2013; Nascimbene et al. 2013), affect lichen diversity in forest complexes. The relative effect of these factors on lichen biota development is difficult to assess (Pinho et al. 2008; Giordani and Brunialti 2015). Moreover, local climatic fluctuations, elevation, and/or land-use intensity drive the local specificity of lichen diversity (Loppi et al. 1997; Giordani 2006; Wolseley et al. 2006; Giordani and Incerti 2008). Generally, old-growth, least-affected lowland deciduous forests are characterised by a high level of lichen diversity, and many rare species are associated with old trees (Hyvärinen et al. 1992; Price and Hochachka 2001; Fritz et al. 2008a, b; Ranius et al. 2008a; Nascimbene et al. 2010a; Bartels and Chen 2012, 2014).

Numerous endangered epiphytic lichens are stenotopic and specially adapted to certain habitat types (Bartels and Chen 2015). These species may be a signal determinant of the natural condition of the forest environment (McCune 2000). The use of a limited number of bioindicators is an alternative and practical approach in environmental assessments (Nitare 2000). The great advantages of such an approach are a short study period, simplicity, and low cost (Will-Wolf et al. 2002; Gao et al. 2015). However, detailed data on the distribution and habitat requirements of lichen indicators are required for correct interpretation of field observations and for appropriate conservation actions and policies (Löhmus and Löhmus 2009; Juriado et al. 2012; Jönsson et al. 2016). Some species may have special conservation value, and thus their protection entails that of naturally co-occurring species and entire biocoenoses (Nilsson et al. 1995; Roberge and Angelstam 2004; Scheidegger and Werth 2009; Ivanowa 2015). Therefore, attention should be also paid to lichen biota directly associated with a particular indicator (Nilsson et al. 1995; Johansson and Gustafsson 2001; Nordén et al. 2007; Nascimbene et al. 2010b).

The impact of various factors on the local occurrence of two epiphytic lichens, Chrysothrix candelaris (L.) J. R. Laundon and Varicellaria hemisphaerica (Flörke) I. Schmitt & Lumbsch, within one type of forest community was examined in this study. These species are commonly used as suitable primeval lowland forest indicators (Coppins and Coppins 2002; Czyżewska and Cieśliński 2003; Motiejūnaitė et al. 2004) and are considered typical inhabitants of forests of above-average biodiversity (Andersson and Kriukelis 2002; Ek et al. 2002). The two species are morphologically distinctive and easy to identify in the field, even by non-specialists; therefore they have a wide practical application in field evaluations. Nevertheless, the lack of parallel contributions of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica in the epiphytic biota of some of the best-preserved European lowland forests is a mystery. It is difficult to find a study on lichens of old-growth lowland forest which does not report the presence of one of these species, yet the simultaneous existence of both populations in similar abundance within a single forest complex is observed only sporadically (Cieśliński and Tobolewski 1988; Zalewska 2012; Malíček and Palice 2013; Kubiak et al. 2016). Therefore, our research was aimed at answering the following questions: (1) Does the current structure of a forest stand affect the distribution of the examined species? If so, to what extent? (2) If so, what kinds of forest stands constitute optimal habitats for these species? (3) If not, are there other factors responsible for their distribution patterns? (4) Are specific assemblages of lichens directly associated with these species due to similar habitat requirements?

These questions seem particularly crucial in the context of the practical use of these lichens as environmental indicators. Moreover, we hypothesise that: (1) the distribution patterns of the examined species are not accidental and result from their narrow ecological amplitude; (2) their vicariance is caused by differences in forest stand structure; (3) both lichen indicators are leading representatives of unique assemblages of species with similar habitat requirements.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

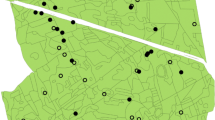

The study was conducted in the Masurian Lakeland (NE Poland), almost one-third of which is covered by forests with a high degree of biodiversity (Faliński 1998). This region constitutes a natural corridor constituting an important environmental communication link in Central Europe (CORINE biotopes 2016). Field studies were carried out in four large forest complexes, in many parts of which oak-hornbeam stands have been preserved in their natural form to the present day: the Puszcza Nidzicka f. (abbr. N), Puszcza Piska f. (abbr. P), Puszcza Borecka f. (abbr. B), and Puszcza Romincka f. (abbr. R) (Fig. 1). The topography of the region is very diverse, as the landscape was formed during the Pomeranian phase of the last Vistula River glaciation (ca 15,200 BP) (Kozarski and Nowaczyk 1999). Denivelations are considerable, reaching as much as 120–140 m a.s.l; the highest point is almost 300 m a.s.l. This region is characterised by zonal climatic variability, with clashes of oceanic, continental, and boreal climate types (Kondracki 1972). Generally, the forest complexes situated further to the north-east, due to the greater impact of arctic air masses and relatively high elevation, experience a colder and more humid climate than those in the south-west. The vegetation period is relatively short, lasting between 160 to 190 days (Jutrzenka-Trzebiatowski 1999). As is apparent from the coverage maps of the Natura 2000 Special Area of Conservation (Interactive Map 2016), the B and R complexes are more compact and their state of preservation is considered more natural than that of the N and P complexes.

Target Lichen Indicators

Chrysothrix candelaris (Online Resource 1) is identified by its bright yellow, diffuse, leprose thallus consisting of minute granules. The sterile form predominates in this species (Fletcher and Purvis 2009). Varicellaria hemisphaerica (Online Resource 1) forms an always sterile, rather thick, pale bluish-grey thallus with a usually broad margin and conspicuous, paler or concolourous, convex soralia (Chambers et al. 2009). Both species reproduce primarily by means of vegetative propagules (soredia); thus they likely possess similar dispersion abilities. The forest complexes under consideration are within the potential distribution range of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica; these species also occur in neighbouring countries (e.g., Litterski 1999; Prigodina Lukošienė and Naujalis 2009; Motiejūnaitė and Prigodina Lukošienė 2010). Generally, the species are characterised by low frequency in Central European forests (Dietrich and Scheidegger 1996; Svoboda et al. 2011) and are considered endangered or threatened in many countries (Piterāns 1996; Scheidegger and Clerc 2002; Cieśliński et al. 2006; Liška et al. 2008). They are sensitive to global environmental risks, although the eutrophication tolerance of C. candelaris is greater than was previously assumed (Pinho et al. 2011).

Sampling Design and Data Collection

The field study was conducted in plots within a single community of a typical old oak-hornbeam forest corresponding to Tilio-Carpinetum Tracz. (see Faliński 1986). Initially, sixty-seven plots (N–20, P–20, B–17, R–10) of 400 m2 each inside the forests, i.e., at a distance of not less than 50 m from the edge of a uniform patch and at least 200 m from the forest line, were randomly selected (see also Friedel et al. 2006; Boch et al. 2013). The definition of a specific habitat as fresh broadleaved forest or fresh mixed deciduous forest, according to forest typology (Forest Data Bank 2016), was the basic criterion for the selection of the study plots. The second criterion was the presence of mature forest stands aged over 100 years. The study plots were not adjacent; up to 2 study plots were analysed within the area of a single forest division (ca 20 ha). The epiphytic lichen biota was examined in terms of the presence of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica. Nearly 900 trees, each with a diameter greater than 10 cm, were inspected. The lichen indicators were found in 50 plots. These plots were taken for further detailed consideration. In order to define the stands, all trees were counted and the diameter at breast height (DBH) of each tree was measured in the study plots. Tree species richness in plots can be considered to represent microhabitat heterogeneity; DBH is the equivalent of an available microhabitat for epiphytic lichens. Subsequently, the detailed scrutiny of epiphytic lichen biota was performed for trees serving as hosts for C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica. The lichens were recorded on the tree trunks at a height of 0–2 m from the ground and classified into five classes according to the percentage scale of coverage: (1) <1%; (2) 1–5%; (3) 5–12.5%; (4) 12.5–50%; (5) >50%.

Lichen Species Identification

The lichens were identified in the field only in cases of taxonomically non-problematic specimens. Most individuals, however, were collected for precise identification based on an examination of their macromorphological and micromorphological and chemical features. The lichens’ secondary compounds were analysed using the standard thin-layer chromatography (TLC) method, according to Orange et al. (2001). The nomenclature of the lichen species follows the Index Fungorum (2016). The collected lichen specimens are housed in the OLTC herbarium.

Other Data Collection

The general coverage participation of coniferous and deciduous trees in the total areas of particular forest complexes (see Fig. 1), along with data on the general age of the forest stands directly corresponding to the particular plots, was derived from the official superintendence documentation; elevation of the plots was derived from detailed topographic maps. The procedure for determining the general age of a forest stand is based on the average age of the dominant tree species. Such an estimate, however, does not take into account the age of the youngest and oldest single trees. In order to characterise the basic weather conditions around the forest complexes, daily reports (relative humidity, precipitation, and mean temperature) from two selected meteorological stations from the beginning of the present century to the end of 2015 were downloaded and calculated, i.e., WMO index 12270 and 12195 (see Fig. 2). The first station is close to the N and P forests; the second is situated between the B and R forests.

Obrothermic diagrams and main weather parameters corresponding to the plots with Chrysothrix candelaris (CH) and Varicellaria hemisphaerica (V). All graphs are prepared on the basis of daily reports from the years 2000–15 obtained from two selected meteorological stations (for details, see Materials and methods). The values above the bars present average annual rainfall. Mean values (points), standard deviation (whiskers), t and p values (significant are given in bold) are shown on small graphs (n = 5844)

Statistical Analyses

The significance of differences between the C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica plots in terms of forest stand structure and elevation were verified with multivariate Hotelling’s T-squared test. The same test was used to compare the data on weather conditions obtained from the meteorological stations. Multiple regression analysis was used to determine which of the independent variables, i.e., the age of the forest stand, number of trees, sum of DBH, and elevation, are the best predictors of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica abundance within their plots. The stepwise forward selection procedure was applied and the Pearson correlation coefficients calculated in advance to check whether any strong correlations (r > 0.90) exist between selected variables. Prior to the analysis, the coverage data were transformed, with the values from classes 2–5 being replaced by the average cover defined for these classes and the value 0.5 arbitrarily used for class 1. In addition to these analyses, differences between the plots with C. candelaris and those with V. hemisphaerica in terms of mean diameters of main host trees were tested with Student’s t-test. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Lilliefors tests were used to verify that the data were normally distributed; Levene’s test was applied to assess the equality of variances. Data which did not meet the assumptions of normality were Box–Cox transformed. When the aforementioned assumptions were not achieved, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used as an alternative. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed to test for differences between forest stands in terms of tree species composition (Anderson 2001); non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to obtain a diagram of the distribution of the plots. These analyses were based on the matrix of tree species abundance in particular study plots using the Bray–Curtis coefficient. NMDS and hierarchical clustering (Ward’s method) were applied to find the general pattern of similarities between lichen biotas (assemblages) directly associated with C. candelaris and with V. hemisphaerica. These analyses were based on the matrix of lichen species abundance using the Bray–Curtis coefficient. Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was performed to show the association of particular lichens with the main host trees for C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica. To eliminate non-specific species, lichens that were common and abundant on all trees were excluded from the analysis. The Shannon diversity indexes, which were general and which took only main trees into account, were calculated for assemblages of lichens associated with C. candelaris and with V. hemisphaerica. The statistical calculations were performed using STATISTICA 12 and PAST 3.10 (Hammer et al. 2001).

Results

Vicariance of Target Lichen

The plots with C. candelaris were limited to the N (15) and P (10) forests, while almost all plots with V. hemisphaerica were located in the B (15) and R (8) forests. The only exceptions to this rule were two plots with V. hemisphaerica within the P forest; however, these were situated at the north-eastern end of the complex. The equal number of plots for both indicators is fortuitous.

Characteristics of Forest Stands

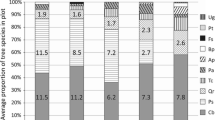

The forest stands undergoing study consisted of 10 tree species: Acer platanoides (A), Betula pendula (B), Carpinus betulus (C), Fraxinus excelsior (F), Picea abies (Pa), Pinus sylvestris (Ps), Populus tremula (Pt), Quercus robur (Q), Tilia cordata (T), Ulmus glabra (U). For the average proportions of the main tree species, see Fig. 3. Carpinus betulus occurred throughout, Quercus robur and Tilia cordata in most of the studied plots, and Acer platanoides in a little over half of the plots; other tree species appeared sporadically. According to the PERMANOVA (F = 1.871, p = 0.121) and NMDS (Online Resource 2) analyses, tree species composition did not differ significantly between the plots with C. candelaris and those with V. hemisphaerica. Among four main tree components of the plots, only the mean diameter of oaks demonstrated a significant and strong correlation with the general age of forest stands. The mean DBH of other trees did not clearly correspond to the estimated age of the forests (Online Resource 3A).

Factors Responsible for Differences between Plots and Affecting the Abundance of the Target Lichens

Hotelling’s T-squared test revealed a highly significant combined effect of the independent variables on differences between the plots with C. candelaris and those with V. hemisphaerica (T 2 = 222.176; p < 0.05). The attributes differentiating the plots were related to the age of forest stands, sum of DBH, and elevation, with the last parameter exerting the most significant effect (Fig. 4); contrastingly, no significant difference in tree density was revealed. To generalise, the plots with C. candelaris are much more low-lying and represent older forest stands, usually composed of more venerable oaks (Fig. 4, Online Resource 3).

Characteristics of forest stands (age, tree density, sum of tree diameters) and elevation of the plots with Chrysothrix candelaris (CH; n = 25) and Varicellaria hemisphaerica (V; n = 25). Mean values (points), standard deviation (whiskers), t and p values (significant are given in bold) are shown on the graphs

According to the multiple regression analysis, the only factor included in the model that positively and significantly (p < 0.05) influenced the abundance of C. candelaris was the age of the forest stand. In the case of V. hemisphaerica, three variables were entered in the model; of these, elevation and sum of DBH positively affect species abundance; however, only the effect of the former proved significant (p < 0.05). Tree density negatively affected the abundance of this lichen in the plots (p < 0.05).

Climate

Annual precipitation in the twenty-first century varied considerably, from 454 to 902 mm, while the average annual temperature ranged between 6 and 9 °C. The weather patterns in the areas of the selected meteorological stations are substantially different. Comparison of the records revealed reliable differences between the main weather parameters (T 2 = 19.176; p < 0.05) and showed that temperatures in the WMO 12270 area were higher than in the WMO 12195 area, while relative humidity and precipitation were lower in the former. Total rainfall for the second station far exceeded 800 mm in some years (see Fig. 2).

Host Tree Specificity of Target Lichens

Roughly half as many trees were inhabited by C. candelaris as by V. hemisphaerica; the totals were 49 and 100, respectively (for exact numbers in relation to particular tree species, see Fig. 5). Hornbeam was the most important host tree only for V. hemisphaerica. In particular, the largest hornbeams in the plots were readily inhabited by specimens of this lichen (Online Resource 3B). Oaks were the main host trees for both lichens, with nearly the same number of recorded trunks. However, oaks appeared to be essential for C. candelaris (Fig. 5); oaks overgrown by this lichen were characterised by significantly greater diameters than those inhabited by V. hemisphaerica (Online Resource 3B). The same applies to maples, though the difference was not significant according to the test. Maple was a preferred host tree for C. candelaris, linden for V. hemisphaerica. Single trunks of Fraxinus, Populus, and Ulmus were incidentally inhabited by V. hemisphaerica (Fig. 5).

Host tree specificity of Chrysothrix candelaris (CH) and Varicellaria hemisphaerica (V) expressed as the total number of particular trees on which specimens of the lichens were recorded. Tree abbreviations: Acer platanoides (A), Carpinus betulus (C), Fraxinus excelsior (F), Populus tremula (Pt), Quercus robur (Q), Tilia cordata (T), Ulmus glabra (U)

General Lichen Species Diversity

Altogether, 105 lichen species were recorded; of this pool, 74 occurred together with C. candelaris and 84 were associated with V. hemisphaerica. Only half of the species (to be exact, 53) turned out to be non-specific, co-occurring with both C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica; the remainder were exclusive to assemblages of lichens associated with only one of these two species. Although a slightly greater number of exclusive species were associated with V. hemisphaerica, the two kinds of assemblages achieved similar average Shannon index values (see Table 1).

Lichen Assemblages

NMDS ordination (Fig. 6) clearly separated the assemblages of lichens associated with C. candelaris (left side of the diagram) from those associated with V. hemisphaerica (right side); the two kinds of assemblages barely overlapped. Similarly, hierarchical clustering revealed two main distinct clusters (Online Resource 4). Cluster 1 included assemblages with C. candelaris, whereas cluster 2 comprised assemblages with V. hemisphaerica. The only disorder consisted of a small subcluster within the main cluster 1 which combined several assemblages associated with C. candelaris with others associated with V. hemisphaerica.

The DCA diagram reflects the host specificity of associated lichen species in the context of trees inhabited by C. candelaris or V. hemisphaerica (Fig. 7). The eigenvalues of axes 1 and 2 were 0.602 and 0.274, respectively. The cumulative percentage of variance accounted by the first two axes equalled 54.2% (37.3% and 16.9% for the first and second axis, respectively). The DCA ordination diagram placed oak and maple with C. candelaris on the left side and grouped tree species with V. hemisphaerica on the right side. A link is evident between the strong host tree specificity of many lichens and their association with either C. candelaris or V. hemisphaerica. Several lichens in the central part of the diagram appear to have no special preference for a particular tree or indicator species.

Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) ordination diagram of the main host trees for Chrysothrix candelaris (A-CH, Acer; Q-CH, Quercus) and Varicellaria hemisphaerica (A-V, Acer; C-V, Carpinus; Q-V, Quercus; T-V, Tilia) and other lichen species associated both with these trees and with C. candelaris/V. hemisphaerica. Lichen species present as singletons are bracketed; for species abbreviations, as follows and see below Table 1. Abbreviations not included in Table 1: Acro gem Acrocordia gemmata, Aman pun Amandinea punctata, Anis pol Anisomeridium polypori, Arth med Arthonia mediella, Baci bia Bacidia biatorina, Baci rub B. rubella, Baci sub B. subincompta, Baci sul B. sulphurella, Buel gri Buellia griseovirens, Cali ads Calicium adspersum, Cali sal C. salicinum, Chae fer Chaenotheca ferruginea, Clad con Cladonia coniocraea, Clad fim C. fimbriata, Dime pin Dimerella pineti, Ever pru Evernia prunastri, Fell gyr Fellhanera gyrophorica, Fusc arb Fuscidea arboricola, Hypo sca Hypocenomyce scalaris, Leca arg Lecanora argentata, Leca chl L. chlarotera, Leca cro Lecania croatica, Leci ele Lecidella eleaochroma, Lepr elo Lepraria elobata, Mela gla Melanelixia glabratula, Mica pra Micarea prasina agg., Micr dis Microcalicium disseminatum, Ochr bah Ochrolechia bahusiensis, Opeg ver Opegrapha vermicellifera, Parm amb Parmeliopsis ambigua, Pert alb Pertusaria albescens, Pert fla P. flavida, Pert lei P. leioplaca, Pert pup P. pupillaris, Pyre nit Pyrenula nitida, Rama pol Ramalina pollinaria, Rino deg Rinodina degeliana, Rino eff R. efflorescens, Ropa vir Ropalospora viridis, Zwac vir Zwackhia viridis

Discussion

Many lichens occupy specific micro-environmental niches and are sensitive to subtle environmental changes (Wirth 1992; Martinez et al. 2014). The results revealed that the occurrence of certain lichens defined as old-growth lowland forests indicators may be strongly influenced by their specific habitat requirements, which may rigorously determine their distribution patterns on a local scale. The localities of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica as a rule did not overlap, even though the examined plots represent the same type of forest stand.

Forest Stand Structure

Many articles underline that tree species diversity and composition is one of the fundamental factors explaining epiphytic species distribution within forests (see Mežaka et al. 2008; Király et al. 2013). However, in this study it turned out that the studied plots could not be differentiated in terms of tree composition (Fig. 3 and Online Resource 2). Neither was there any significant difference in tree density. Thus it can be assumed that canopy closure and light availability were comparable in all of the plots (Fig. 4). The age of a stand is another key factor responsible for lichen biodiversity and composition (Fritz et al. 2008a, b; Nascimbene et al. 2010b). The oak-hornbeam forest stands inhabited by C. candelaris were generally older than those populated by V. hemisphaerica (Fig. 4). Additionally, the general age of forest stands was the only factor to positively affect the abundance of C. candelaris in the plots. It might simply be assumed that C. candelaris is attached to older forests. However, this species also appeared in the neighbouring 120-year-old mixed managed forests, provided that big oaks were present (Kubiak et al. 2016). Moreover, only the mean diameter of oaks in the plots, which was the essential host tree for C. candelaris (Fig. 5), significantly correlated—at least in this study (Online Resource 3a)—with the age of forest stands. Aged oaks, which are more likely to remain in old and unaffected oak-hornbeam stands, provide the microhabitat space necessary for C. candelaris. Varicellaria hemisphaerica has been frequently recorded in deciduous forests of uneven age, including those over two hundred years old (e.g., Fritz et al. 2008b). Therefore, we assume that the estimated fifty-year difference in the general age of current stands is not a direct and key factor regulating the occurrence of these species. It is very likely that the qualitative and age structure of the forest complex considered as a whole on a large-landscape scale has a greater influence on distribution patterns than the stand parameters directly characterising the examined plots. Although the coverage participation of forest stands over a hundred years old in the N and P complexes (approximately a third of the total) is somewhat higher than in B and R (less than one-fifth), the total participation of deciduous trees in the first two complexes falls within the vicinity of 10% (see Fig. 1). We believe that the vast total area of deciduous forest consistent with the habitat, along with its relatively low fragmentation, is of great importance for maintenance of V. hemisphaerica. On the other hand, C. candelaris showed no sensitivity to this general factor and even tended to colonise old mixed forests of anthropogenic origin (see Kubiak et al. 2016) or natural forests under strong human influence (Motiejūnaitė 2009).

The Impact of Climatic Conditions

The occurrence of the examined lichen indicators is highly dependent on the geographical location of the forest complexes in which they grow. A relatively slight difference in location may be associated with quite different climate parameters. The studied complexes lie at similar distances from the coast of the Baltic Sea (about 100–150 km) and are not subject to the direct influence of a maritime climate. However, considering the study area, C. candelaris clearly prefers south-western complexes (the N and P forests), V. hemisphaerica north-eastern (the B and R forests). The complexes comfortable for V. hemisphaerica are located in an area with significantly higher relative humidity and precipitation as well as lower mean temperature compared to those preferred by C. candelaris (Fig. 2). The preference of C. candelaris for drier habitats and the attachment of V. hemisphaerica to moderately moist habitats are suggested based on an overview of the data in the literature (Fabiszewski and Szczepańska 2010). According to Wirth (2010), both lichens are characterised by similar ecological indicator values, although the moisture value is somewhat higher for V. hemisphaerica. The presence of C. candelaris in mixed forests with a high proportion of pine (see Kubiak et al. 2016) also indirectly suggests its low sensitivity to dehumidify of habitat (see also von Arx et al. 2012). The highest annual rainfalls in north-eastern Poland, which regularly exceed 700 mm, occur in the region of the R forest. These values are typical for the coastal zone of western Poland, where V. hemisphaerica is characterised by the highest frequency in the lowland part of the country within the beech distribution range (Fałtynowicz 1992). Mean annual precipitation is the most effective ecological predictor of the occurrence and diversity of many lichens (Svoboda et al. 2010; Merinero et al. 2014). In central Spain, V. hemisphaerica has been classified among the group of lichens very sensitive to the ‘edge of forest effect’ and strongly prefers the forest interior (Belinchón et al. 2007; Aragón et al. 2015). On the other hand, in Western European areas with very high humidity, this species appears in open habitats (Tønsberg 1992; Chambers et al. 2009). The dependence of V. hemisphaerica on climatic conditions and sufficient moisture of habitat may explain its low prevalence in the Białowieża Forest (Cieśliński 2003), one of the best preserved natural lowland forests in Europe, where suitable host trees certainly exist, but where annual rainfall and relative humidity are not as high as in the B and R forest complexes (Faliński 1986). Understanding the climatic sensitivity of species is a central theme in biodiversity conservation. Climate and response to climate change is one component among a large number of drivers which interact to control the occurrence of lichens (Lisewski and Ellis 2011).

The Impact of Topography

Vertical distribution patterns of lichens have been usually investigated in mountain areas (Çobanoğlu and Sevgi 2009; Nascimbene and Marini 2015); the significance of elevation for lichen occurrence in the lowlands is rarely taken into consideration. However, the topography of some lowland areas may be characterised by highly diversified relief and great differences in elevation which often induce local climatic fluctuations. The average height above sea level of the B and R forests is higher by about 50 m than that of the N and P forests (Fig. 4). The elevation forces the convection of polar maritime air masses on the slopes of moraine hills and, furthermore, promotes condensation of water vapour in the air, consequently increasing the amount of rainfall (Huggett and Cheesman 2002). In the end, elevation turned out to be the only factor (rather than variables describing the general structure of stands) positively and significantly affecting V. hemisphaerica abundance within the plots. This is another point indicating the high moisture requirements of the species.

Host Tree Specificity of Lichens

The presence of large old trees in the forest complex undoubtedly favours the occurrence of C. candelaris, which demonstrates strong dependence on oak trunks (Fig. 5 and Online Resource 3B). The age and bark structure of trees are among the most important factors determining the occurrence of certain epiphytes (Uliczka and Angelstam 1999; Johansson et al. 2007; Fritz et al. 2008a; Marmor et al. 2011). The average age of forest stands for plots with C. candelaris amounted to nearly 200 years; hence old and massive oaks have been preserved in large numbers in these forest complexes. The stands (including oaks) in the B and R forests are younger (Fig. 4); this may be one of the important causes for the negligible presence of C. candelaris in these complexes (see also Zalewska and Fałtynowicz 2004; Zalewska 2012; Forest Data Bank 2016). The same applies to maples, though C. candelaris shows a lesser preference for the trunks of this tree. The greater total sum of tree diameters and mean diameter of oaks and maples in the plots with C. candelaris compared to those with V. hemisphaerica (Fig. 4 and Online Resource 3B) suggests that the former species requires the provision by suitable host trees of a sufficiently large microhabitat surface. The positive impact on lichen species richness exerted by a high density of oaks in the immediate area in a larger landscape has been demonstrated (Ranius et al. 2008a, b; Paltto et al. 2010). Moreover, old oaks constitute almost the only harbour for C. candelaris in old managed forests planted in habitats typical of temperate deciduous forest (Kubiak et al. 2016). Numerous sources of lichen propagules and their proximity to suitable trees increase the probability that other trees will be colonised by epiphytic lichens (Johansson et al. 2009). In natural forests (e.g., the Białowieża Forest), where C. candelaris occurs abundantly, it sometimes grows on different trees (Cieśliński and Tobolewski 1988; Cieśliński 2003). Perhaps large and firmly established populations show greater tolerance in regard to host trees.

Varicellaria hemisphaerica is characterised by a much lower level of specialisation regarding species and age of host trees. Even though the number of plots with C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica was the same, the latter was recorded on twice as many trees. V. hemisphaerica was recorded on almost all species of deciduous trees, with the exception of birch. However, hornbeam and oak constituted its main preferences (Fig. 5) and hornbeams with a large diameter were favoured by individuals (Online Resource 3b). In other deciduous forests, the thalli of V. hemisphaerica also readily overgrow beech bark, and this lichen can also be encountered on alders, hazels, and rowans (Fałtynowicz 1992; Cieśliński 2003). The bark of oaks, hornbeams, and lindens is fairly acidic (Barkman 1958; Jüriado et al. 2009) but the structure of these kinds of bark differs at various stages of the trees’ lives. It seems that a porous periderm structure, which appears only in old hornbeams, is an important factor for this lichen (Mežaka et al. 2008). In the Baltic countries, at the extremes of beech and hornbeam zone coverage, V. hemisphaerica inhabits mainly oaks (Prigodina Lukošienė and Naujalis 2006; Motiejūnaitė et al. 2008). The wide tolerance of V. hemisphaerica in relation to host trees may explain its frequency (twice that of C. candelaris) in the studied plots.

Specific Assemblages of Lichens

Although our target species were C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica, the study also concerned more than 100 accompanying lichen species. It can be stated that a large part of the lichen epiphytic biota characteristic of this type of forest community has been found to be directly associated with these indicators (cf. Cieśliński et al. 1995; Mežaka et al. 2008; Jüriado et al. 2009; Motiejūnaitė and Prigodina Lukošienė 2010; Svoboda et al. 2010, 2011). A slightly higher number of species recorded together with V. hemisphaerica results from the greater diversity of main host trees (Table 1 and Fig. 5). Both indicators co-create specific assemblages of epiphytic lichens (Fig. 6 and Online Resource 4) characterised by a high number of exclusive species (Table 1). These assemblages are similar in terms of species diversity but differ significantly in terms of species composition. Moreover, many lichens with high conservation value are integrated in both sets of lichens. Among the red-listed and endangered lichens in Poland (according to Cieśliński et al. 2006), Arthonia byssacea and Calicium viride (for the C. candelaris assemblage) and Arthonia vinosa, Pertusaria coronata, P. pertusa, Pyrenula nitida, and P. nitidella (for the V. hemisphaerica assemblage) were recorded most often. The great distinctness of the C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica assemblages is symptomatic and indicates that their exclusive members exhibit similar habitat requirements. In addition, the intimacy of many accompanying species is frequently manifested in relation not only to C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica but also to their main host trees (Fig. 7). Environmental evaluation should consider not only the separate occurrence of individual species but also the occurrence of sets of species forming specific communities. Assemblages of certain lichens are characterised by a high level of repeatability, whereas the appearance of individual species may be coincidental and insufficient for a proper diagnosis (see also Rola and Osyczka 2014).

Conclusions: Management Implications and Conservation Value

Oak-hornbeam forests constitute the primary type of potential vegetation over large lowland areas of Europe, but at the same time are, due to agricultural expansion and the cultivation of wood-productive pines and spruces, the most endangered (Matuszkiewicz 2008). Therefore, this forest community has been included in the ecological network of special protected areas in Europe known as Natura 2000. One of the main objectives of this project (Council Directive 1992) is to preserve or restore valuable natural habitats. In practice, specifying the present condition of the habitat and determining the size of the protective area to be established for successful maintenance of the habitat are not simple tasks. Well-chosen lichen indicators can be of great assistance in such endeavours. Notwithstanding, the objective specification of lichen habitat requirements should be accomplished first, in order to define their actual indicative application.

Certain lichens are readily used to ascribe conservational value to old forest stands or natural woodlands (Nordén and Appelqvist 2001). Based on species composition, many biotas closely related to specific forest communities have been reported, and numerous lichens have been appointed as indicators of ‘ecological continuity’ (e.g., Rose 1974), ‘primeval (virgin) forest’ (e.g., Cieśliński et al. 1996), or ‘lowland old-growth forest’ (Czyżewska and Cieśliński 2003; Motiejūnaitė et al. 2004). Imprecise definitions of these concepts, ambiguous criteria for the selection of such indicators, and, consequently, interpretations of environmental information potentially provided by the occurrence of these lichens, often give rise to dispute (e.g., Nordén and Appelqvist 2001; Rolstad et al. 2002; Nordén et al. 2014). Specific local habitat parameters, the period required for the effective colonisation of suitable substrates, and natural disturbances of forest structure may in fact constitute key factors responsible for lichen biota development and the presence or absence of particular species (Kalwij et al. 2005). Our research showed that identification of potential habitat factors affecting the occurrence and abundance of particular indicators in the greatest possible detail is a desirable step towards the verification of their true bioindicative usefulness, especially in the context of a regional environmental evaluation.

Varicellaria hemisphaerica is not host-specific and readily inhabits trunks of various deciduous trees. A sufficiently high level of moisture in the habitat is essential for the species, which prefers forests with a high proportion of deciduous trees on a large-landscape scale. Habitat continuity on the level of the local landscape is more important for this species than the current age and structure of forest stands; thus, this lichen appears to be a good indicator of the ecological continuity of regional varieties of oak-hornbeam forest (see also Kubiak 2011, Kubiak and Łubek 2016). The opposite pattern is demonstrated by Chrysothrix candelaris. Among the many factors that determine the specificity of a given habitat, its occurrence basically depends on only one, i.e., the microhabitat space provided by old oaks. The lack of such trees in a given stand may seriously inhibit the lichen. Thus, its role as a general indicator of forest continuity in the context of a whole habitat is very limited.

Regardless of the indicative value, our study proved that localities within oak-hornbeam forests inhabited by both C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica deserve special protection status. Many exclusive and endangered lichens with similar habitat requirements are associated with these two species (Table 1). Protecting their habitats may indirectly ensure the effective protection of many other lichens that make up coherent and stable epiphytic biotas. Moreover, the spontaneous restoration of deciduous forest areas consistent with the habitat, along with the associated lichen biota, is possible within a relatively short period. The occurrences of C. candelaris individuals on oaks in human-transformed mixed forests should be regarded as a positive phenomenon that may indicate that the process of natural regeneration is underway (see also Kubiak et al. 2016). Dense populations of C. candelaris and V. hemisphaerica may be a useful environmental tool for the designation of protected areas as ‘forests possessing unique environmental value’, according to the criteria of the High Conservation Value Forests programme HCVF (WWW 2007).

References

Anderson MJ (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Ecol Appl 26:32–46

Andersson L, Kriukelis R (2002) Pilot Woodland Key Habitat Inventory in Lithuania. Final Report. Vilnius. http://www.pro-natura.net/publikat-filer/Final-report-Lithuania-2002.pdf

Aragón G, Abuja L, Belinchón R, Martínez I (2015) Edge type determines the intensity of forest edge effect on epiphytic communities. Eur J Forest Res 134:443–451

Barbier S, Gosselin F, Balandier P (2008) Influence of tree species on understory vegetation diversity and mechanisms involved – a critical review for temperate and boreal forests. For Ecol Manage 254:1–15

Barkman JJ (1958) Phytosociology and ecology of cryptogamic epiphytes. Van Gorcum, Assen

Bartels SF, Chen HYH (2012) Mechanisms regulating epiphytic plant diversity. Crit Rev Plant Sci 31:391–400

Bartels SF, Chen HYH (2014) Dynamics of epiphytic macrolichen abundance, diversity, and composition in boreal forest. J Appl Ecol 52:181–189

Bartels SF, Chen HYH (2015) Species dynamics of epiphytic macrolichens in relation to time since fire and host tree species in boreal forest. J Veg Sci 26:1124–1133

Belinchón R, Martínez I, Escudero A, Aragón G, Valladares F (2007) Edge effects on epiphytic communities in a Mediterranean Quercus pyrenaica forest. J Veg Sci 18:81–90

Boch S, Müller J, Prati D, Blaser S, Fischer M (2013) Up in the tree – the overlooked richness of bryophytes and lichens in tree crowns. PLoS ONE 8:e84913

Chambers SP, Gilbert OL, James PW, Aptroot A, Purvis OW (2009) Pertusaria DC. (1805). In: Smith CW, Aptroot A, Coppins BJ, Fletcher A, Gilbert OL, James PW, Wolseley PA (eds) The lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. The British Lichen Society, London, pp 673–689

Cieśliński S (2003) Atlas rozmieszczenia porostów (Lichenes) w Polsce Północno-Wschodniej. Phytocoenosis 15 (NS). Suppl Cartograph Geobot 15:1–426 (in Polish)

Cieśliński S, Czyżewska K, Fabiszewski J (2006) Red list of the lichens in Poland. In: Mirek Z, Zarzycki K, Wojewoda W, Szeląg Z (eds) Red list of plants and fungi in Poland, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, PASc, Kraków, pp 71–89

Cieśliński S, Czyżewska K, Faliński J B, Klama H, Mułenko W, Żarnowiec J (1996) Relicts of the primeval (virgin) forest. Relict phenomena. In: Faliński JB, Mułenko W (eds) Cryptogamous plants in the forest communities of Białowieża National Park (Project CRYPTO 3). Phytocoenosis 8 (NS), Archiv Geobot (Vol 6). Polish Botanical Society, Warszawa-Białowieża, pp 197–216

Cieśliński S, Czyżewska K, Glanc K (1995) Lichenes. In: Faliński JB, Mułenko W (eds) Cryptogamous plants in the forests communities of Białowieża National Park. General problems and taxonomic groups analysis (Project CRYPTO). Phytocoenosis 7 (NS), Archiv Geobot (Vol 4). Polish Botanical Society, Warszawa-Białowieża, pp 75–86

Cieśliński S, Tobolewski Z (1988) Porosty (Lichenes) Puszczy Białowieskiej i jej zachodniego przedpola. Phytocoenosis 1 (NS). Suppl Cartogr Geobot 1:3–216 (in Polish)

Çobanoğlu G, Sevgi O (2009) Analysis of the distribution of epiphytic lichens on Cedrus libani in Elmali Research Forest (Antalya, Turkey). J Environ Biol 30:205–212

Coppins A, Coppins BJ (2002) Indices of Ecological Continuity for woodland epiphytic lichen habitats in the British Isles. British Lichen Society, London

Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 On the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31992L0043&from=EN

Corine biotopes (2016) European Environment Agency. http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/corine-biotopes#tab-european-data

Coxson DS, Nadkarni NM (1995) Ecological roles of epiphytes in nutrient cycles of forest ecosystems. In: Lowman MD, Nadkarni NM (eds) Forest canopies. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 495–543

Czyżewska K, Cieśliński S (2003) Porosty – wskaźniki niżowych lasów puszczańskich w Polsce. Monogr Bot 91:223–239 (in Polish)

Dietrich M, Scheidegger Ch (1996) The importance of sorediate crustose lichens in the epiphytic lichen flora of the Swiss Plateau and the pre-alps. Lichenologist 28(3):245–256

Ek T, Suško U, Auzinš R (2002) Inventory of Woodland Key Habitats methodology. Riga. http://www.uv.es/elalum/assessmr/LatWKHMethod2002.pdf

Ellenberg H (1988) Vegetation ecology of Central Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ellis CJ (2012) Lichen epiphyte diversity: a species, community and trait-based review. Perspec Plant Ecol 14:131–152

Fabiszewski J, Szczepańska K (2010) Ecological indicator values of some lichen species noted in Poland. Acta Soc Bot Pol 79:305–313

Faliński JB (1986) Vegetation dynamics in temperate lowland primeval forest. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht

Faliński JB (1998) Maps of anthropogenic transformations of plant cover (maps of synanthropization). Phytocoenosis 10 (NS). Suppl Cartog Geobot 9:15–54

Faliński JB, Mułenko W (1995) Cryptogamous plants in the forests communities of Białowieża National Park. General problems and taxonomic groups analysis (Project CRYPTO). Phytocoenosis 7 (NS). Archiv Geobot 4:3–176

Fałtynowicz W (1992) The lichens of Western Pomerania. An ecogeographical study. Polish Bot Stud 4:1–183

Fletcher A, Purvis OW (2009) Chrysothrix Mont. (1852). In: Smith CW, Aptroot A, Coppins BJ, Fletcher A, Gilbert OL, James PW, Wolseley PA (eds) The lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. The British Lichen Society, London, pp 307–309

Forest Data Bank (2016) Bureau for Forest Management and Geodesy, The State Forests, Ministry of the Environment. Sękocin Stary-Warszawa. http://www.bdl.lasy.gov.pl

Friedel A, Oheimb GV, Dengler J, Härdtle W (2006) Species diversity and species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens – a comparison of managed and unmanaged beech forests in NE Germany. Feddes Repert 117:172–185

Fritz Ö, Gustafsson L, Larsson K (2008a) Does forest continuity matter in conservation? – A study of epiphytic lichens and bryophytes in beech forests of southern Sweden. Biol Conserv 141:655–668

Fritz Ö, Niklasson M, Churski M (2008b) Tree age is a key factor for the conservation of epiphytic lichens and bryophytes in beech forests. Appl Veg Sci 12:93–106

Gao T, Busse Nielsen A, Hedblom M (2015) Reviewing the strength of evidence of biodiversity indicators for forest ecosystems in Europe. Ecol Indic 57:420–434

Giordani P (2006) Variables influencing the distribution of epiphytic lichens in heterogeneous areas: a case study for Liguria, NW Italy. J Veg Sci 17:195–206

Giordani P, Brunialti G (2015) Sampling and interpreting lichen diversity data for biomonitoring purposes. In: Upreti DK et al. (eds) Recent Advances in Lichenology. Springer (India), New Delhi-Heidelberg-New York-Dordrecht-London, pp 19–46

Giordani P, Incerti G (2008) The influence of climate on the distribution of lichens: a case study in a borderline area (Liguria, NW Italy). Plant Ecol 195:257–272

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron 4:1–9

Hauck M, de Bruyn U, Leuschner C (2013) Dramatic diversity losses in epiphytic lichens in temperate broad-leaved forests during the last 150 years. Biol Conserv 157:136–145

Hugget RJ, Cheesman J (2002) Topography and the Environment. Pearson Education, Harlow

Hyvärinen M, Halonen P, Kauppi M (1992) Influence of stand age and structure on the epiphytic lichen vegetation in the middle-boreal forests of Finland. Lichenologist 24:165–180

Index Fungorum (2016) Landcare Research and RBG Kew: Mycology. http://www.indexfungorum.org

Interactive Map (2016) Interactive map of Natura 2000. http://geoserwis.gdos.gov.pl/mapy

Ivanowa NV (2015) Factors limiting distribution of the rare lichen species Lobaria pulmonaria in forests of the Kologriv forest nature reserve. Biol Bull 42:145–153

Johansson P, Gustafsson L (2001) Red-listed and indicator lichens in woodland key habitats and production forests in Sweden. Can J For Res 31:1617–1628

Johansson P, Rydin H, Thor G (2007) Tree age relationships with epiphytic lichen diversity and lichen life history traits on ash in southern Sweden. Ecoscience 14:81–91

Johansson V, Bergman K-O, Lättman H, Milberg P (2009) Tree and site quality preferences of six epiphytic lichens growing on oaks in southeastern Sweden. Ann Bot Fennici 46:496–506

Jönsson MT, Ruete A, Kellner O, Gunnarsson U, Snäll T (2016) Will forest conservation areas protect functionally important diversity of fungi and lichens over time? Biodivers Conserv. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-1035-0

Jüriado I, Karu L, Liira J (2012) Habitat conditions and host tree properties affect the occurrence, abundance and fertility of the endangered lichen Lobaria pulmonaria in wooded meadows of Estonia. Lichenologist 44:263–276

Jüriado I, Liira J, Paal J, Suija A (2009) Tree and stand level variables influencing diversity of lichens on temperate broad-leaved trees in boreo-nemoral floodplain forests. Biodivers Conserv 18:105–125

Jutrzenka-Trzebiatowski A (1999) Wpływ człowieka na szatę leśną Polski północno-wschodniej w ciągu dziejów. Rozprawy i Materiały Ośrodka Badań Naukowych im. W. Kętrzyńskiego w Olsztynie 184:1–171 (in Polish)

Kalwij JM, Wagner HH, Scheidegger C (2005) Effects of stand-level disturbances on the spatial distribution of a lichen indicator. Ecol Appl 15:2015–2024

Király I, Nascimbene J, Tinya F, Ódor P (2013) Factors influencing epiphytic bryophyte and lichen species richness at different spatial scales in managed temperate forests. Biodivers Conserv 22:209–223

Kondracki J (1972) Polska Północno-Wschodnia. PWN, Warszawa (in Polish)

Kozarski S, Nowaczyk B (1999) Paleogeografia Polski w vistulanie. In: Starkel L (ed) Geografia Polski. Środowisko przyrodnicze. PWN, Warszawa, pp 79–103 (in Polish)

Kubiak D (2011) Distribution and ecology of the lichen Fellhanera gyrophorica in the Pojezierze Olsztyńskie Lakeland and its status in Poland. Acta Soc Bot Pol 80:293–300

Kubiak D, Łubek A (2016) Bacidia hemipolia f. pallida in Poland – distribution and ecological characteristics based on new records from old-growth forests. Herzogia 29:712–720

Kubiak D, Osyczka P, Rola K (2016) Spontaneous restoration of epiphytic lichen biota in managed forests planted on habitats typical for temperate deciduous forest. Biodiv Conserv 25:1937–1954

Leppik E, Jüriado I (2008) Factors important for epiphytic lichen communities in wooded meadows of Estonia. Folia Cryptog Estonica 44:75–87

Lisewski V, Ellis ChJ (2011) Lichen epiphyte abundance controlled by the nested effect of woodland composition along macroclimatic gradients. Fungal Ecol 4:241–249

Liška J, Palice Z, Slavíková Š (2008) Checklist and red list of lichens of the Czech Republic. Preslia 80:151–182

Litterski B (1999) Pflanzengeographishe und ökologishe bewertung der Flechtenflora Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns. J Cramer, Berlin-Stuttgart (in German)

Lõhmus P, Lõhmus A (2009) The importance of representative inventories for lichen conservation assessments: the case of Cladonia norvegica and C. parasitica. Lichenologist 4:61–67

Loppi S, Pirintsos SA, De Dominicis V (1997) Analysis of the distribution of epiphytic lichens on Quercus pubescens along an altitudinal gradient in a Mediterranean area (Tuscany, CentralItaly). Isr J Plant Sci 45:53–58

Malíček J, Palice Z (2013) Lichens of the virgin forest reserve Žofínský prales (Czech Republic) and surrounding woodlands. Herzogia 26(2):253–292

Marini L, Nascimbene J, Nimis PL (2011) Large-scale patterns of epiphytic lichen species richness: photobiont-dependent response to climate and forest structure. Sci Total Environ 409:4381–4386

Marmor L, Tõrra T, Saag L, Randlane T (2011) Effects of forest continuity and tree age on epiphytic lichen biota in coniferous forests in Estonia. Ecol Indic 11:1270–1276

Martinez J-JI, Raz R, Mgocheki N, Álvarez R (2014) Epiphytic lichen is associated with species richness of gall-inducing aphids but not with niche differentiation among them. Arth-Plant Int 8:17–24

Matuszkiewicz JM (2008) Zespoły leśne Polski. PWN, Warszawa (in Polish)

McCune B (2000) Lichen communities as indicators of forest health. Bryologist 103:353–356

Merinero S, Rubio-Salcedo M, Aragón G, Imartínez I (2014) Environmental factors that drive the distribution and abundance of a threatened cyanolichen in southern Europe: a multi-scale approach. Am J Bot 101:1876 –1885

Mežaka A, Brūmelis G, Piterāns A (2008) The distribution of epiphytic bryophyte and lichen species in relation to phorophyte characters in Latvian natural old-growth broad leaved forests. Folia Cryptog Estonica 44:89–99

Moning Ch, Werth S, Dziock F, Bässler C, Bradtka J, Hothorn T, Müller J (2009) Lichen diversity in temperate montane forests is influenced by forest structure more than climate. For Ecol Manage 258:745–751

Motiejūnaitė J (2009) Lichens and allied fungi of two regional parks in Vilnius area (Lithuania). Acta Mycol 44(2):185–199

Motiejūnaitė J, Alstrup V, Randlane T, Himelbrant D, Stonèius D, Hermansson J, Urbanavichus G, Suija A, Fritz Ö, Prigodina Lukošienė I, Johansson P (2008) New or interesting lichens, lichenicolous and allied fungi from Birzai District, Lithunia. Bot Lith 14:29–42

Motiejūnaitė J, Czyżewska K, Cieśliński S (2004) Lichens – indicators of old-growth forests in biocentres of Lithuania and North-East Poland. Bot Lith 10:59–74

Motiejūnaitė J, Prigodina Lukošienė I (2010) Lichens and allied fungi of Dūkštos Oak Forest (Neris regional park, Eastern Lithuania). Bot Lith 16:115–123

Nascimbene J, Brunialti G, Ravera S, Frati L, Caniglia G (2010b) Testing Lobaria pulmonaria (L.) Hoffm. as an indicator of lichen conservation importance of Italian forests. Ecol Indic 10:353–360

Nascimbene J, Marini L (2015) Epiphytic lichen diversity along elevational gradients: biological traits reveal a complex response to water and energy. J Biogeogr 42:1222–1232

Nascimbene J, Marini L, Nimis PL (2010a) Epiphytic lichen diversity in old-growth and managed Picea abies stands in alpine spruce forests. For Ecol Manage 260:603–609

Nascimbene J, Thor G, Nimis PL (2013) Effects of forest management on epiphytic lichens in temperate deciduous forests of Europe – a review. For Ecol Manage 298:27–38

Nilsson S, Arup U, Baranowski R, Ekman S (1995) Tree-dependent lichens and beetles as indicators in conservation forests. Conserv Biol 9:1208–1215

Nimis PL, Martellos S (2001) Testing the predictivity of ecological indicator values. A comparison of real and virtual releves of lichen vegetation. Plant Ecol 157:165–172

Nitare J (2000) Signalarter – Indikatorer på skyddsvärd skog. Flora över kryptogamer. NBF, Jönköping (in Swedish)

Nordén B, Appelqvist T (2001) Conceptual problems of ecological continuity and its bioindicators. Biodiv Conserv 10:779–791

Nordén B, Dahlberg A, Brandrud TE, Fritz Ö, Ejrnaes R, Ovaskainen O (2014) Effects of ecological continuity on species richness and composition in forests and woodlands: a review. Ecoscience 21:34–45

Nordén B, Paltto H, Götmark F, Wallin K (2007) Indicators of biodiversity, what do they indicate? Lessons for conservation of cryptogams in oak-rich forest. Biol Conserv 135:369–379

Orange A, James PW, White FJ (2001) Microchemical methods for the identification of lichens. British Lichen Society, London

Paltto H, Thomasson I, Norden B (2010) Multispecies and multiscale conservation planning: setting quantitative targets for red-listed lichens on ancient oaks. Conserv Biol 24:758–768

Pinho P, Augusto S, Maguas C, Pereira MJ, Soares A, Branquinho C (2008) Impact of neighbourhood land-cover in epiphytic lichen diversity: analysis of multiple factors working at different spatial scales. Environ Poll 151:414–422

Pinho P, Dias T, Cruz C, Tang YS, Sutton M, Martins-Loução MA, Máguas C, Branquinho C (2011) Using lichen functional-diversity to assess the effects of atmospheric ammonia in Mediterranean woodlands. J Appl Ecol 48:1107–1116

Piterāns A (1996) Kērpji. In: Andrušaitis G (ed) Latvijas Sarkanā Grāmata. Retās un izzūdošās augu un dzīvnieku sugas. 1 sējums. Sēnes un ķērpji. Latvian Academy of Sciences, Riga, Salaspils, pp 117–196

Price K, Hochachka G (2001) Epiphytic lichen abundance: effects of stand age and composition in coastal British Columbia. Ecol Appl 11:904–913

Prigodina Lukošienė I, Naujalis JR (2006) Principal relationships among epiphytic communities on common oak (Quercus robur L.) trunks in Lithuania. Ekologija 2:21–25

Prigodina Lukošienė I, Naujalis JR (2009) Rare lichen associations on common oak (Quercus robur) in Lithuania. Biologia 64(1):48–52

Ranius T, Eliasson P, Johansson P (2008a) Large-scale occurrence patterns of red listed lichens and fungi on old oaks are influenced both by current and 15 historical habitat density. Biodiv Conserv 17:2371–2381

Ranius T, Johansson P, Berg N, Niklasson M (2008b) The influence of tree age and microhabitat quality on the occurrence of crustose lichens associated with old oaks. J Veg Sci 19:653–662

Roberge J-M, Angelstam P (2004) Usefulness of the umbrella species concept as a conservation tool. Conserv Biol 18:76–85

Rola K, Osyczka P (2014) Cryptogamic community structure as a bioindicator of soil condition along a pollution gradient. Environ Monit Assess 186:5897–5910

Rolstad J, Gjerde I, Gundersen VS, Saetersdal M (2002) Use of indicator species to asses forest continuity – a critique. Conserv Biol 16(1):253–257

Rose F (1974) The epiphytes of oak. In: Morris MG, Perring FH (eds) The British oak. Its history and natural history. EW Classey, Faringdon, pp 250–273

Scheidegger C, Clerc P (2002) Rote Liste der gefährdeten Arten der Schweiz: Baum- und erdbewohnende Flechten. Hrsg. Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft BUWAL, Bern, und Eidgenössische Forschungsanstalt WSL, Birmensdorf, und Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève CJBG. BUWAL-Reihe Vollzug Umwelt (in German)

Scheidegger C, Werth S (2009) Conservation strategies for lichens: insights from population biology. Fungal Biol Rev 23:55–66

Seaward MRD (2008) Environmental role of lichens. In: Nash TH (ed) Lichen Biology, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 274–298

Sillet SC, Antoine ME (2004) Lichens and bryophytes in forest canopies. In: Lowman MD, Rinker HB (eds) Forest canopies. Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, pp 151–174

Svoboda D, Peksa O, Veselá J (2010) Epiphytic lichen diversity in central European oak forests: assessment of the effects of natural environmental factors and human influences. Environ Poll 158:812–819

Svoboda D, Peksa O, Veselá J (2011) Analysis of the species composition of epiphytic lichens in Central European oak forests. Preslia 83:129–144

Tønsberg T (1992) The sorediate and isidiate, corticolous, crustose lichens in Norway. Sommerfeltia 14:1–331

Uliczka H, Angelstam P (1999) Occurrence of epiphytic macrolichens in relation to tree species and age in managed boreal forest. Ecography 22:396–405

von Arx G, Dobbertin M, Rebetez M (2012) Spatio-temporal effects of forest canopy on understory microclimate in a long-term experiment in Switzerland. Agricult Forest Meterol 166–167:144–155

Will-Wolf S, Esseen PA, Neitlich P (2002) Monitoring biodiversity and ecosystem function: forests. In: Nimis PL, Scheidegger C, Wolseley PA (eds) Monitoring with Lichens-Monitoring Lichens, vol. 7. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 203–222

Wirth V (1992) Zeigerwerte von Flechten. In: Ellenberg H, Weber HE, Düll R, Wirth V, Werner W Paulissen D (eds) Zeigerwerte von Pflanzen in Mitteleuropa. Scripta Geobot 18:215–237 (in German)

Wirth V (2010) Ökologische Zeigerwerte von Flechten – erweiterte und aktualisierte Fassung. Herzogia 23:229–248 (in German)

Wolseley PA, Stofer S, Mitchell A-M, Vanbergen A, Chimonides J, Scheidegger C (2006) Variation of lichen communities with land use in Aberdeenshire, UK. Lichenologist 38:307–322

WWW [World-wide Found for Nature] (2007) High Conservation Value Forests: The concept in theory and practice. WWF International. Gland, Switzerland. https://www.hcvnetwork.org/resources/folder.2006-09-29.6584228415/hcvf_brochure_012007.pdf

Zalewska A (2012) Ecology of lichens of the Puszcza Borecka Forest (NE Poland). W. Szafer Institute of Botany, PASc, Kraków

Zalewska A, Fałtynowicz W (2004) Lichens of the protected areas in the Euroregion Niemen. Published by Association “Man and Nature”, Suwałki

Acknowledgements

The study was partially supported by the National Science Centre (Decision No. N N304 203737).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kubiak, D., Osyczka, P. Specific Vicariance of Two Primeval Lowland Forest Lichen Indicators. Environmental Management 59, 966–981 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0833-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0833-4