Abstract

Aim

Predicting progression in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is critical to improving outcomes. We sought to develop/validate a machine-learned, prognostic risk score (KidneyIntelX™) combining electronic health records (EHR) and biomarkers.

Methods

This is an observational cohort study of patients with prevalent DKD/banked plasma from two EHR-linked biobanks. A random forest model was trained, and performance (AUC, positive and negative predictive values [PPV/NPV], and net reclassification index [NRI]) was compared with that of a clinical model and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) categories for predicting a composite outcome of eGFR decline of ≥5 ml/min per year, ≥40% sustained decline, or kidney failure within 5 years.

Results

In 1146 patients, the median age was 63 years, 51% were female, the baseline eGFR was 54 ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2, the urine albumin to creatinine ratio (uACR) was 6.9 mg/mmol, follow-up was 4.3 years and 21% had the composite endpoint. On cross-validation in derivation (n = 686), KidneyIntelX had an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI 0.74, 0.79). In validation (n = 460), the AUC was 0.77 (95% CI 0.76, 0.79). By comparison, the AUC for the clinical model was 0.62 (95% CI 0.61, 0.63) in derivation and 0.61 (95% CI 0.60, 0.63) in validation. Using derivation cut-offs, KidneyIntelX stratified 46%, 37% and 17% of the validation cohort into low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups for the composite kidney endpoint, respectively. The PPV for progressive decline in kidney function in the high-risk group was 61% for KidneyIntelX vs 40% for the highest risk strata by KDIGO categorisation (p < 0.001). Only 10% of those scored as low risk by KidneyIntelX experienced progression (i.e., NPV of 90%). The NRIevent for the high-risk group was 41% (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

KidneyIntelX improved prediction of kidney outcomes over KDIGO and clinical models in individuals with early stages of DKD.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately one out of four adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus has kidney disease (i.e., diabetic kidney disease [DKD]). Each year, 50,000 individuals with DKD progress to kidney failure in the United States [1]. The Mount Sinai Health System alone provides care for over 70,000 patients with DKD. Measurements of eGFR and urinary albumin creatinine ratio (uACR) have been incorporated into the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for risk stratification [2], but these cannot precisely identify patients who will experience rapid kidney function decline (RKFD) [3]. As a result, primary care physicians and diabetologists are not able to appropriately risk stratify and counsel patients on the progressive nature of DKD. Easily interpretable and accurate prognostic tools that integrate into clinical workflow are lacking, resulting in suboptimal treatment and delays in referral to a nephrology specialist. This has led, in part, to the unacceptable burden of progressive DKD and kidney failure [4,5,6,7,8] with a high proportion of patients starting unplanned dialysis [1, 9, 10].

Several blood-based biomarkers have shown associations with DKD progression, most significantly soluble TNF receptors 1/2 (TNFR1/2) and plasma kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) [11, 12]. However, accurate prognostic models that combine clinical data from patients’ electronic health records (EHR) with blood-based biomarkers have not been implemented. Although EHR data are widely available, its volume and complexity limits integration with biomarker values using traditional methodologies. Machine learning can combine biomarkers and EHR data to produce prognostic risk scores. We previously demonstrated that combining biomarkers and EHR data in patients with type 2 diabetes and APOL-1 high-risk genotype improved prediction of kidney outcomes over clinical models [13]. A simple risk score that improves the ability to identify patients with DKD at low, intermediate, and high risk of progressive decline in kidney function has the potential to improve outcomes through more effective use of medications and efficient resource allocation at the primary care physician level.

In this study, we sought to develop and validate the performance of a new biomarker-enriched, machine-learned risk score (the KidneyIntelX™ test) to predict progressive decline in kidney function in patients with early-stage DKD and compare the performance with standard clinical models. We also determined risk-based thresholds that can easily be integrated into standard clinical workflows and enhance existing clinical practice guidelines.

Methods

Study sample

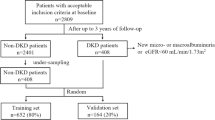

Samples were from the BioMe Biobank at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB). The BioMe Biobank is a biorepository of plasma and DNA collected from 2007 from individuals in a diverse local community in New York City. Informed consent for access to the patients’ EHR is also included [14, 15]. PMBB is a biobank of blood and tissue samples taken from a research cohort recruited via the University of Pennsylvania Health System from 2008 [14]. Participants gave consent for their biospecimens to be linked with their longitudinal EHR (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Fig. 1). Both BioMe and PMBB are institutional biobanks that attempt to be representative of the patient populations of the institutions they serve. Patients are recruited from outpatient general medicine clinics and certain subspecialty clinics with limited pre-selection criteria [16, 17].

The study protocol was approved by each institution’s review board; all participants had provided written informed consent to participate in research and were not specifically compensated for participation in the current study. Blood was collected on the day of enrolment into BioMe or PMBB and plasma was isolated as per standard procedures and continuously stored at −80°C until shipping to the RenalytixAI laboratory, USA where biomarkers were measured.

Inclusion criteria

We selected patients from BioMe and PMBB who were 21–81 years at the time of biobank enrolment (‘baseline’), with type 2 diabetes, an eGFR between 30 and 59.9 ml min−1 [1.73 m]2 or an eGFR ≥60 ml min−1 [1.73 m]2 with uACR ≥3 mg/mmol. The KDIGO risk model categorises patients based on eGFR and albuminuria and has three colours that correspond to the prognosis of prevalent CKD (we did not include patients at ‘low risk’ or green because they do not have CKD) [2]. Patients were included if, by the KDIGO eGFR and uACR criteria, they were stage G3a–G3b with all grades of albuminuria (A1–A3) and stage G1–G2 with moderate to high albuminuria (uACR ≥30 mg/g [A2–A3]) [2]. The proportion of each DKD stage was evaluated against national estimates derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2018–2019 [18]. For eGFR, we defined the baseline period as 1 year before or up to 3 months after biobank enrolment. Baseline uACR values were derived from closest values ±1 year from enrolment to maximise sample size as these are measured less frequently; participants without baseline values of eGFR and uACR meeting these criteria were excluded. Only individuals with a stored plasma specimen, a minimum follow-up time from enrolment of at least 21 months, at least three eGFR values after baseline (ESM Fig. 1) were included. Individuals with kidney transplants or on chronic maintenance dialysis before baseline were excluded from the study.

Ascertainment of clinical variables

Data on sex and race were obtained from the BioMe and PMBB biobanks or from EHR data. Clinical data were extracted for all EHR variables with concordant time stamps. Hypertension and type 2 diabetes status at baseline were determined using the eMERGE Network phenotyping algorithms [16]. CVD and heart failure were determined by ICD-9/10 clinical modification codes.

Biomarker assays

The three plasma biomarkers were measured in a proprietary, analytically validated multiplex format using the Mesoscale platform (MesoScale Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA), which employs electrochemiluminescence detection methods combined with patterned arrays to multiplex assays. Each sample was run in duplicate, along with quality control samples with known low, moderate and high concentrations of each biomarker on each plate. Assay precision was assessed using a reference panel of seven samples that spanned the measurement range. Intra-assays for KIM-1, TNFR1 and TNFR2 gave mean CV values of 3.9%, 5.4%, and 3.7%, respectively. Inter-assays for KIM-1, TNFR-I, and TNFR-2 reference samples gave mean CV values of 9.9%, 10.1%, and 7.8%, respectively. Assays satisfied dilution linearity and were run at 1:4 dilution. Levey–Jennings plots were employed and followed the Westgard rules for re-run of samples. The laboratory personnel performing the biomarker assays were blinded to all clinical information.

Data harmonisation

We harmonised data from BioMe and PMBB biobanks. Race/ethnicity was collapsed into four major, non-overlapping categories (White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other). ICD and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were included as yes/no variables with timestamps. Medications (including metformin, insulin, sulfonylureas, etc. that were prescribed before the baseline data) were mapped to RxNorm codes [19] and laboratory values to Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) codes [20]. Only variables represented in >70% of participants throughout the combined dataset (except uACR and BP because of their established clinical importance) were included and used to train the KidneyIntelX algorithm.

Ascertainment and definition of the kidney endpoint

We determined eGFR using the CKD-EPI creatinine equation [21]. We employed linear mixed models with an unstructured variance-covariance matrix and random intercept/slope for each individual to estimate the eGFR slope [22]. The primary composite outcome, progressive decline in kidney function, included the following: RKFD defined as an eGFR slope decline of ≥5 ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2 per year [2], a sustained (confirmed at least 3 months later) decline in eGFR of ≥40% [23] from baseline, or ‘kidney failure’ defined by sustained eGFR <15 ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2 confirmed at least 30 days later, or receipt of long-term maintenance dialysis or receipt of a kidney transplant [2]. Additionally, two nephrologists (SC, GNN) independently adjudicated all outcomes examining each individual over their longitudinal course, accounting for eGFR changes (ensuring annualised decline of ≥5 ml/min or ≥40% sustained decrease), corresponding ICD/CPT codes and medications to ensure that outcomes represented true decline rather than a context dependent temporary change (e.g., due to medications/hospitalisations). Follow-up time was censored after loss to follow-up, after the date that the non-slope components of the composite kidney endpoint were met, or 5 years after baseline.

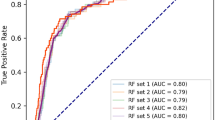

Statistical analysis

The datasets were randomised into derivation (60%) and validation sets (40%). The validation dataset was completely blinded and sequestered from the total derivation dataset. Using only the derivation set, we evaluated supervised random forest algorithms on the combined biomarker and all structured EHR features without a priori feature selection and identified a candidate feature set using grid search; ESM Table 1. The derivation set was then randomly split into secondary training and test sets for model optimisation with 70%–30% spitting and a tenfold cross-validation for AUC. We considered both raw values and ratios of the biomarkers. Missing uACR values were imputed to 1.1 mg/mmol [24], missing BP values were imputed using multiple predictors (age, sex, race and antihypertensive medications) [25], and median values were used for other features where missingness was <30% (ESM Table 2).

We conducted further iterations of the model by tuning the individual hyperparameters. A hyperparameter is a parameter that is used to control the learning process (e.g., number of random forest trees) as opposed to parameters whose weights are learned during the training (e.g., weight of a variable). Tuning hyperparameters refers to iteration of model architecture after setting parameter weights to achieve the ideal performance. Hyperparameters were optimised using the grid search approach. K-fold cross-validation-based AUC was evaluated for all possible combinations of hyperparameters. We selected the combination of hyperparameters that optimised the AUC for model building. The following hyperparameters were considered for optimisation.

-

Number of variables randomly selected as candidates for splitting a node

-

Mean forest number of unique cases (data points) in a terminal node

-

Maximum depth to which a tree should be grown

The code for hyperparameter optimisation has been deposited in a github repository (https://github.com/girish-nadkarni/KidneyIntelX_hyperparameter_tuning) to improve reproducibility and transparency. The final model was selected based on AUC performance.

We generated risk probabilities for the composite kidney endpoint using the final model in the derivation set, scaled them to align with a continuous score from 5 to 100 by increments of 5, and applied this score to the validation set. Risk cut-offs were chosen in the derivation set to encompass the top 15% as the high-risk (scores 90–100), bottom 45% as the low-risk (scores 5–45), and the intervening 40% as the intermediate-risk group (scores 50–85). Primary performance criteria were AUC, positive predictive value (PPV) for high-risk group and negative predictive value (NPV) for low-risk group at the pre-determined cut-offs. The selected model and associated cut-offs were then validated by an independent biostatistician (MK) in the sequestered validation cohort.

In addition to these traditional test statistics, we assessed calibration by examining the slope of observed vs expected outcome plots of the KidneyIntelX score vs only the observed outcomes. We also constructed Kaplan–Meier curves for time-dependent outcomes of 40% decline and kidney failure with HRs using the Cox proportional hazards method.

The discrimination of the KidneyIntelX model was compared with a recently validated comprehensive clinical model that included age, sex, race, eGFR, CVD, smoking, hypertension, BMI, uACR, insulin, diabetes medications, and HbA1c and was developed to predict 40% eGFR decline in individuals with type 2 diabetes [24]. Utility metrics (PPV, NPV) were compared with both the comprehensive clinical model and KDIGO risk strata. We also calculated the net reclassification index (NRI) for events and non-events compared with KDIGO risk strata [26, 27]. Finally, we compared the validated KidneyIntelX model with a logistic regression model incorporating the features found to be significantly driving the outcome. All a priori levels of significance were <0.05. All hypothesis tests were two-sided. 95% confidence intervals were calculated by bootstrapping. All analyses were performed with R software (www.rproject.org), the dplyr package, the randomForestSRC and the CARET package [28, 29].

Results

Baseline characteristics of cohorts

Baseline characteristics of the total study cohort (n = 1146) were as follows: median age 63 years, 581 (51%) female, median eGFR 54 ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2, and median uACR 6.9 mg/mmol. uACR was available in 62% of the cohort and imputed to 1.1 mg/mmol in 38%. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (91%), CAD (35%), and heart failure (33%). The majority (81%) were on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Baseline characteristics between derivation and validation sets including event rates were balanced. The median number of serum creatinine/eGFR values per participant during the follow-up period was 16 (Table 1). The distribution of DKD stages of the study cohort is similar to national estimates based on NHANES (ESM Table 3).

Prediction of the composite kidney endpoint (progressive decline in kidney function)

Overall, 241 patients (21%) experienced progressive decline in kidney function over a median 4.3 (IQR 3.0–4.8) years. In the complete derivation set (n = 686), using tenfold cross-validation for discrimination, the mean AUC for the KidneyIntelX model was 0.77 (95% CI 0.74, 0.79). The most significant data features contributing to performance of the KidneyIntelX model included the three plasma biomarkers (TNFR1, TNFR2 and KIM1, as discrete values and ratios), eGFR, uACR, and systolic BP (Fig. 1). This final model had an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI 0.76, 0.79) in the validation set (n = 460). The risk for the composite kidney event increased by predicted probabilities of the KidneyIntelX score (Fig. 2a and b) and by the KidneyIntelX score (Fig. 2c). The slope of the observed vs the predicted risk for KidneyIntelX was 0.8 in the training set and 1.0 in the validation set, indicating good calibration (ESM Fig. 2). By comparison, the comprehensive clinical model yielded an AUC of 0.62 (95% CI 0.61, 0.63) in the full derivation set (n = 686) and 0.61 (95% CI 0.60, 0.63) in validation set (n = 460; Delong p value for KidneyIntelX vs clinical model <0.001).

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) plot showing relative feature importance. SHAP summary plots order features based on their importance. Each plot is made up of individual points from the training dataset with a higher value being darker purple and a lower value being more yellow. If the dots on one side of the middle line are more purple or yellow, this suggests that the values are increasing or decreasing, respectively, moving the prediction in that direction. For example, higher systolic BP is associated with higher risk of the composite kidney outcome. AST, aspartate aminotransferase

Composite kidney endpoint event rates by (a) KidneyIntelX predicted risk in derivation set, (b) KidneyIntelX predicted risk in validation set and (c) KidneyIntelX score prediction distributions of patients with DKD according to the risk of composite kidney endpoint in the derivation and validation set. (a, b) Events are denoted with an orange dot (progression) and represent the composite kidney endpoint within 5 years. Non-events are denoted with blue dots (no progression) and represent an absence of the composite kidney event in the follow-up period. (c) Dots represent cumulative incidence: blue, low risk 10% (6%, 14%); pink, intermediate risk 22% (16%, 28%); and red, high risk 61% (50%, 71%)

KidneyIntelX clinical utility cut-off points

The risk probability cut-offs of KidneyIntelX selected in the derivation set (n = 686) were 0.061 for the lowest 45% of patients and 0.302 for the top 15% of patients. When these risk cut-offs were applied to the complete validation set, with imputed uACR for missing values (n = 460), KidneyIntelX stratified patients to low- (46%), intermediate- (37%) and high-risk (17%) groups with respective probabilities for the composite kidney endpoint of 0.10, 0.22 and 0.61. When the optimised clinical model was applied to the validation set, the respective probabilities for the composite kidney endpoint were 0.171 for the bottom 46% of the population and 0.319 for the top 17%. Thus, the PPV for the composite kidney endpoint was 61% in the KidneyIntelX high-risk group compared with a PPV of 37% for the comprehensive clinical model (p < 0.001; Table 2). The NPV for the composite kidney endpoint in the KidneyIntelX low-risk group was 90% compared with an NPV of 88% for the comprehensive clinical model (p = 0.33). The distribution of patients into KDIGO risk categories was established using 296 participants (64%) with uACR available in the validation cohort and stratified the population into ‘moderately increased risk’ (53%), ‘high risk’ (31%) and ‘very high risk’ (16%) with respective probabilities of 0.15, 0.29 and 0.40 for the composite kidney endpoint over 5 years. In the subgroup with non-imputed uACR (n = 296), the PPV for the high-risk strata of KidneyIntelX was 69% (compared with 40% for KDIGO ‘very high’ risk) and the NPV for the low-risk strata of KidneyIntelX was 93% (compared with 85% for KDIGO ‘moderately increased’ risk; ESM Table 4).

KidneyIntelX scores correctly classified more cases into the appropriate risk strata (NRIevent = 55% in the derivation set and 41% in the validation set, p < 0.05; ESM Table 5) than the KDIGO risk strata did. NRInon-event was −8.2% in the derivation set and − 7.9% in the validation set (p = NS).

Time-to-event analyses for 40% sustained decline or kidney failure

Patients with high-risk KidneyIntelX scores (top 15% in the derivation set and top 17% in the validation set) had greater risk of progression to time-to-event categorical outcomes of 40% sustained decline or kidney failure than patients in the low- or medium-risk strata combined did (HR 9.2; 95% CI 6.2, 13.6 in derivation and 9.1, 95% CI 5.8, 14.4 in the validation set; Fig. 3a and b). Kaplan–Meier curves by KDIGO risk categories in the training and validation set are shown in ESM Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves by KidneyIntelX risk strata for the endpoint of sustained 40% decline in eGFR or kidney failure in derivation (a) and validation (b) sets. The risk cut-offs derived from derivation and applied to validation were: low risk 0–0.061129, intermediate risk 0.061129–0.30209 and high risk 0.30209–1. In the derivation set, 45% were low risk, 40% were intermediate risk and 15% were high risk. In the validation set, 46% were low risk, 37% were intermediate risk, and 17% were high risk. The HR for high vs low risk was 18.3 (95% CI 10.1, 33.1) in derivation and 14.7 (95% CI 7.8, 27.6) in validation. The HR for high vs intermediate risk was HR 5.7 (95% CI 3.7, 8.7) in derivation and 6.0 (95% CI 3.5, 10.0) in validation. The HR for high vs low and intermediate risk combined was 9.2 (95% CI 6.2, 13.6) in derivation and 9.1 (95% CI 5.8, 14.4) in validation

Subgroup analysis

KidneyIntelX performed similarly across patients with an eGFR greater or less than 60 ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2 at baseline (0.78 and 0.76, respectively). Additionally, when only data in the year prior to enrolment were included, the AUC was identical (0.77) as was the PPV for the top 17% (61%) and the NPV for the bottom 45% (91%). Kaplan–Meier plots did not change when limited to patients with data ≥5 years to ensure that patients were alive for at least 5 years (ESM Fig. 4).

Comparison with logistic regression model

We compared the performance of a logistic regression model that incorporated the top 12 final features that were trained and validated in the KidneyIntelX random forest model. The AUC for a logistic model with those 12 features was 0.75, and the PPV for the top 17% of the population was 59%.

Discrimination for ‘kidney failure’ endpoint

Using the same KidneyIntelX model specifically trained for the composite kidney endpoint, the AUC of KidneyIntelX risk scores for the ‘kidney failure’ endpoint alone was 0.87 (95% CI 0.84, 0.89) in the derivation cohort and 0.89 (95% CI 0.87, 0.91) in the validation cohort.

Discussion

Utilising plasma samples of individuals with type 2 diabetes from two biobanks and linked EHR data, we developed and validated a risk score combining clinical data and three plasma biomarkers via a random forest algorithm to predict a composite kidney outcome, progressive decline in kidney function, consisting of RKFD, sustained 40% decline in eGFR, and kidney failure over 5 years. We demonstrated that the KidneyIntelX outperformed models that use standard clinical variables alone, including the KDIGO risk categories [2]. There were marked improvements in discrimination over clinical models, as measured by AUC, NRI and improvements in PPV compared with KDIGO risk categories. Furthermore, we showed that KidneyIntelX accurately identified over 40% more patients experiencing events than the KDIGO risk strata did. Finally, KidneyIntelX provided good risk stratification for the accepted US Food and Drug Administration endpoint of sustained 40% decline in eGFR or kidney failure with a 15-fold difference in risk between the high-risk and low-risk strata for this clinical and objective endpoint.

DKD is an increasingly complex and common problem challenging modern healthcare systems. In real world practice, predicting DKD progression is challenging, particularly in early disease, so improving prognostic tests is paramount. Our integrated risk score has near-term clinical implications, especially when linked to clinical decision support and embedded care pathways. The current standard for clinical risk stratification (KDIGO risk strata) [2] has three risk strata that overlap with the population of DKD patients that we included in our study. We also created a risk score with three risk strata (low, intermediate and high) incorporating KDIGO classification components (eGFR and uACR), as well as other clinical variables and three blood-based biomarkers. In this way, we were able to augment the ability to accurately risk stratify patients with DKD, thereby enabling improved patient management.

Low-risk patients with DKD can continue care with their existing providers and require less intense treatments, unless repeat testing, changes in clinical status or local arrangements regarding referral to specialist care indicate otherwise. For those with high-risk scores, oversight may include more referrals to nephrology [30, 31], increased monitoring intervals, improved awareness of kidney health, referral to dieticians, reinforcement of usage of antagonists of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system, and increased motivation to start recently approved medications, including SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists to slow progression [32, 33]. Earlier engagement with nephrologists may also allow for more time to advise and educate patients about home-based dialysis and pre-emptive or early kidney transplant as patient-centred kidney replacement options when appropriate. The use of a risk score as part of the enrolment process in future RCTs may enrich the trial participants for greater likelihood of events and thus reduce the chances for type 2 error or minimise the sample size needed to detect a statistically significant difference between treatment and control. Interventions that prevent or slow DKD progression and foster patient-centred kidney replacement modalities support the goals of the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Advancing American Kidney Health initiative [34].

KidneyIntelX included inputs from biomarkers examined in several settings. These biomarkers have demonstrated reliable independent prognostic signals for kidney function decline and ESRD [11, 12, 15, 35,36,37,38]. In our previous study, we found that including biomarkers to clinical data derived from EHR at a single-centre had better predictive performance than clinical models alone [13]. However, that study included few patients with prevalent CKD (approximately one third had CKD in the cohort with type 2 diabetes and one quarter had CKD in the APOL1 high-risk cohort). In our current study, we expanded the cohort to a second medical centre (University of Pennsylvania), and trained and validated a new model focused exclusively on patients with prevalent DKD at baseline. By incorporating biomarker concentrations and EHR data into our machine learning algorithm, we were able to provide a multidimensional representation of risk for individuals with DKD and allow for the model to generate improved prognostic estimates for future progression [39, 40]. Other biomarkers (e.g., SUPAR) and composite tests that incorporate other plasma biomarkers (apolipoprotein A-IV, CD5 antigen-like, IGF-binding protein 3) and some clinical data features have been shown to accurately predict incident CKD in individuals with type 2 diabetes; however, this does not exclude other approaches that include additional biomarkers and novel methods of data analysis [41,42,43]. The goal of the KidneyIntelX test is to determine which patients with established DKD are at highest risk of progressive decline in kidney function or kidney failure and those with CKD that is unlikely to progress over time.

Our study has limitations. uACR was missing in 38% of the cohort, but this is representative of current state of care [1, 44]. Moreover, our goal was to develop a risk score using real world data from EHR to predict where uACR is missing in a significant number of patients. More widespread availability of uACR values would enhance the performance of KidneyIntelX, as it was a contributing feature in our model. However, even with this limitation, KidneyIntelX had a more robust performance than the KDIGO very high-risk stratum in the subpopulation with uACR measurements. Second, there was no protocolised follow-up resulting in missing data and lack of kidney biopsies. Missing data can lead to biased machine learning models and the data are prone to ascertainment bias [45]. However, the median number of eGFR values per participant was 16, and the median time of follow-up was 4.3 years. Although the primary biobanked cohorts used in the study were broadly representative of individuals with DKD in type 2 diabetes in terms of race/ethnicity and gender, we cannot rule out an inherent bias since the recruitment was opt-in recruitment from outpatient clinics and individuals who chose to participate in the cohorts from which the study population was selected may be different from those who did not participate in the primary cohorts. Additionally, we did not have information on the participants’ socioeconomic status or the duration of the diabetes diagnosis. In the absence of biopsy, we could not exclude the possibility that CKD may be due to other causes. The test performance of KidneyIntelX (random forest algorithm) was higher than a logistic regression model that utilised the final top biomarker and clinical features that were selected by the random forest approach. However, we chose to employ the machine learning approach because random forests can integrate feature selection and modelling as well as efficiently model potential non-linear interactions between features. Finally, both cohorts are from Northeast USA and an independent validation cohort is needed to ensure generalisability. However, only one third of the participants were white, so there was adequate representation of racial groups that experience disparities for kidney disease.

In conclusion, a machine-learned model combining plasma biomarkers and EHR data significantly improved prediction of progressive decline in kidney function over comprehensive clinical models without biomarkers in individuals with DKD in type 2 diabetes from two large academic medical centres.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CPT:

-

Current procedural terminology

- DKD:

-

Diabetic kidney disease

- EHR:

-

Electronic health records

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- KIM-1:

-

Kidney injury molecule-1

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive values

- NRI:

-

Net reclassification index

- PMBB:

-

Penn Medicine Biobank

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive values

- RKFD:

-

Rapid kidney function decline

- TNFR1/2:

-

TNF receptors 1/2

- uACR:

-

Urinary albumin creatinine ratio

References

USRDS (2018) Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

KDIGO (2012) Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3:1–163

Dunkler D, Gao P, Lee SF et al (2015) Risk prediction for early CKD in type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10(8):1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10321014

Agrawal V, Ghosh AK, Barnes MA, McCullough PA (2009) Perception of indications for nephrology referral among internal medicine residents: a national online survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4(2):323–328. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03510708

Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR (2006) Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48(2):192–204. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.073

Hingwala J, Wojciechowski P, Hiebert B et al (2017) Risk-based triage for nephrology referrals using the kidney failure risk equation. Can J Kidney Health Dis 4:2054358117722782. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054358117722782

Kagoma YK, Weir MA, Iansavichus AV et al (2011) Impact of estimated GFR reporting on patients, clinicians, and health-care systems: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 57(4):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.029

Sprangers B, Evenepoel P, Vanrenterghem Y (2006) Late referral of patients with chronic kidney disease: no time to waste. Mayo Clin Proc 81(11):1487–1494. https://doi.org/10.4065/81.11.1487

Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Chertow GM, Tamura MK (2011) Predialysis nephrology care of older patients approaching end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 171(15):1371–1378. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.360

Gillespie BW, Morgenstern H, Hedgeman E et al (2015) Nephrology care prior to end-stage renal disease and outcomes among new ESRD patients in the USA. Clin Kidney J 8(6):772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfv103

Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J et al (2012) Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23(3):507–515. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2011060627

Coca SG, Nadkarni GN, Huang Y et al (2017) Plasma biomarkers and kidney function decline in early and established diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28(9):2786–2793. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016101101

Chauhan K, Nadkarni GN, Fleming F et al (2020) Initial validation of a machine learning-derived prognostic test (KidneyIntelX) integrating biomarkers and electronic health record data to predict longitudinal kidney outcomes. Kidney 360. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0002252020

Damrauer SM, Chaudhary K, Cho JH et al (2019) Association of the V122I hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis genetic variant with heart failure among individuals of African or Hispanic/Latino ancestry. JAMA 322(22):2191–2202. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.17935

Nadkarni GN, Chauhan K, Verghese DA et al (2018) Plasma biomarkers are associated with renal outcomes in individuals with APOL1 risk variants. Kidney Int 93(6):1409–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.01.026

Tayo BO, Teil M, Tong L et al (2011) Genetic background of patients from a university medical center in Manhattan: implications for personalized medicine. PLoS One 6(5):e19166. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019166

Bajaj A, Ihegword A, Qiu C et al (2020) Phenome-wide association analysis suggests the APOL1 linked disease spectrum primarily drives kidney-specific pathways. Kidney Int 97(5):1032–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.01.027

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2019) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2018–2019. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm. Accessed Jan 2020

Bandelow B, Baldwin DS, Dolberg OT, Andersen HF, Stein DJ (2006) What is the threshold for symptomatic response and remission for major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder? J Clin Psychiatry 67(9):1428–1434

Baldwin JA, Johnson RM, Gotz NK, Wayment HA, Elwell K (2006) Perspectives of college students and their primary health care providers on substance abuse screening and intervention. J Am Coll Heal 55(2):115–119. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.55.2.115-120

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH et al (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150(9):604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

Leffondre K, Boucquemont J, Tripepi G, Stel VS, Heinze G, Dunkler D (2015) Analysis of risk factors associated with renal function trajectory over time: a comparison of different statistical approaches. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30(8):1237–1243. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfu320

Levey AS, Inker LA, Matsushita K et al (2014) GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 64(6):821–835. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.030

Nelson RG, Grams ME, Ballew SH et al (2019) Development of risk prediction equations for incident chronic kidney disease. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.17379

De Silva AP, Moreno-Betancur M, De Livera AM, Lee KJ, Simpson JA (2017) A comparison of multiple imputation methods for handling missing values in longitudinal data in the presence of a time-varying covariate with a non-linear association with time: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 17(1):114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0372-y

Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, D'Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS (2008) Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27(2):157–172; discussion 207-112. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2929

Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, Steyerberg EW (2010) Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 30(1):11–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4085

Hadley Wickham RF, Henry L, Müller K (2020) dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R Package version 0.7.6. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html

Hemant Ishwaran UBK (2020) randomForestSRC: fast unified Random Forests for Survival, Regression, and Classification (RF-SRC). Available from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForestSRC/index.html

Smart NA, Dieberg G, Ladhani M, Titus T (2014) Early referral to specialist nephrology services for preventing the progression to end-stage kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD007333. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007333.pub2

Smart NA, Titus TT (2011) Outcomes of early versus late nephrology referral in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Med 124(11):1073–1080 e1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.026

Kristensen SL, Rorth R, Jhund PS et al (2019) Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 7(10):776–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9

Sarafidis P, Ferro CJ, Morales E et al (2019) SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for nephroprotection and cardioprotection in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. A consensus statement by the EURECA-m and the DIABESITY working groups of the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34(2):208–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfy407

Mehrotra R (2019) Advancing American kidney health: an introduction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14(12):1788. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.11840919

Tummalapalli L, Nadkarni GN, Coca SG (2016) Biomarkers for predicting outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 25(6):480–486. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0000000000000275

Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH et al (2012) Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23(3):516–524. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2011060628

Krolewski AS, Niewczas MA, Skupien J et al (2014) Early progressive renal decline precedes the onset of microalbuminuria and its progression to macroalbuminuria. Diabetes Care 37(1):226–234. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0985

Bhatraju PK, Zelnick LR, Shlipak M, Katz R, Kestenbaum B (2018) Association of soluble TNFR-1 concentrations with long-term decline in kidney function: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29(11):2713–2721. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2018070719

Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS et al (2016) Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA 315(2):164–174. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18202

Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J et al (2011) A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305(15):1553–1559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.451

Peters KE, Xu J, Bringans SD et al (2020) PromarkerD predicts renal function decline in type 2 diabetes in the canagliflozin cardiovascular assessment study (CANVAS). J Clin Med 9(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103212

Peters KE, Davis WA, Ito J, Bringans SD, Lipscombe RJ, Davis TME (2019) Validation of a protein biomarker test for predicting renal decline in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. J Diabetes Complicat 33(12):ARTN 107406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.07.003

Hayek SS, Sever S, Ko YA et al (2015) Soluble urokinase receptor and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 373(20):1916–1925. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1506362

Tummalapalli SL, Powe NR, Keyhani S (2019) Trends in quality of care for patients with CKD in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14(8):1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00060119

Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G (2018) Potential biases in machine learning algorithms using electronic health record data. JAMA Intern Med 178(11):1544–1547. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3763

Role of funder

RenalytixAI was involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Duality of interest

GNN, MD and SGC receive financial compensation as consultants and advisory board members for RenalytixAI, and own equity in RenalytixAI. GNN and SGC are scientific co-founders of RenalytixAI. GM, MWK and JAV are consultants for RenalytixAI. FF and JRM are executive directors and BM is a non-executive director of RenalytixAI. SGC has received consulting fees from CHF Solutions, Relypsa, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Takeda Pharmaceuticals in the past 3 years. GNN has received operational funding from Goldfinch Bio and consulting fees from BioVie Inc., AstraZeneca, Reata and GLG consulting in the past 3 years. SMD received research support to the University of Pennsylvania from RenalytixAI for the current study, and consulting fees from Calico Labs outside the current work. LC receives consulting fees from GLG consulting outside of the submitted work.

This research was supported by RenalytixAI. GNN is supported by a career development award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (K23DK107908) and is also supported by R01DK108803, U01HG007278, U01HG009610 and 1U01DK116100. SGC and GNN are members and are supported in part by the Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarker Consortium (U01DK106962). SGC also has salary and research support from the following grants: R01DK106085, R01 DK115562, R01HL85757, R01DK112258, R01DK126477 and U01OH011326. SMD is supported by IK2-CX001780. This publication does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. LC is supported by a career development grant from the NIDDK (K23DK124645).

Funding

This project was funded by RenalytixAI plc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GNN, FF, MJD and SGC made substantial contributions to the study conception, data analysis and data interpretation along with drafting and critical revision of the content. SMD, MWK, JRM, PC, GM, BM, MJD and LC made substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of the data, along with drafting and critical revision of the content. FES and JAV made substantial contributions to interpretation of the data and critical revisions of the content. All authors approve the final version to the manuscript to be published. SGC, GNN, and FF had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM

(PDF 1025 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, L., Nadkarni, G.N., Fleming, F. et al. Derivation and validation of a machine learning risk score using biomarker and electronic patient data to predict progression of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 64, 1504–1515 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05444-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05444-0