Abstract

Road safety has come a long way in our lifetimes, and there are steps in this progress that mark their place in history. Many of these were technical innovations, such as seat belts, electronic stability control, and geofencing for vehicle speed control. Also important, though perhaps fewer in number, were innovations in strategies to achieve change. These include the public health model of Dr. William Haddon, the introduction of Vision Zero, the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention from WHO and the World Bank, and more recently, the Decade of Action 2011–2020. I am sure that the work and recommendations presented in this report will deserve their place in a “Hall of Fame” for strategic innovation in saving lives across the globe.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Foreword

Road safety has come a long way in our lifetimes, and there are steps in this progress that mark their place in history. Many of these were technical innovations, such as seat belts, electronic stability control, and geofencing for vehicle speed control. Also important, though perhaps fewer in number, were innovations in strategies to achieve change. These include the public health model of Dr. William Haddon, the introduction of Vision Zero, the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention from WHO and the World Bank, and more recently, the Decade of Action 2011–2020. I am sure that the work and recommendations presented in this report will deserve their place in a “Hall of Fame” for strategic innovation in saving lives across the globe.

Our report and recommendations are based on the introduction of 2030 Agenda, often referred to as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With the establishment of these Goals in 2015, road safety was explicitly included for the first time as part of the global development agenda, and this heightened recognition gives us a new and unique opportunity to accelerate progress. This recognition puts road traffic safety on the same level of global criticality as climate, health, and equity issues and means that road safety can no longer be traded off in order to promote other needs. Inclusion among the SDGs also means that road safety is the responsibility of a wide range of stakeholders, both public and private. While some might see this as an imposition, I see it as hope and an opportunity to use our knowledge to achieve a vision of mobility without fear for our lives.

In this report, we point out that road safety is a necessity for health, climate, equity, and prosperity. If children cannot walk or bicycle to school without risking their lives, we limit their access to education, good health, and freedom and consequently our hope for the future. If we cannot transport goods across a nation or around the world in a safe and sustainable way, we limit the possibility of trade, economic development, and elimination of poverty. If our workplaces are not safe, we threaten earnings and the sustainability of families. Elimination of deaths and serious injuries in road traffic is essential to many other sustainability goals in very direct and clear ways. Road traffic safety can no longer develop in isolation.

The SDGs have been widely endorsed, and their achievement is now accepted as a central responsibility by governments, corporations, and civil society. Expectations for meaningful contributions by these organizations are driving public attitudes and even affecting investment decisions. Sustainability reporting has become a means for organizations to demonstrate their societal value, and new tools are needed to help them communicate their contributions in an accurate and transparent way. Cities and corporations can do fantastic things to protect the public and create a more livable environment with improved security, better health, and cleaner air.

I am proud to have led a group of internationally recognized road safety thought leaders to formulate the vision, strategy, and rationale underlying these recommendations. Capturing the wisdom of these leaders was among the most challenging tasks I have undertaken, but also the most rewarding. The ideas in the report were developed by consensus. Each member of the group made concessions in our personal viewpoints, but gained insight and knowledge from the others. All of us are proud to stand behind the product of our collaboration, and that is in the end what counts!

Executive Summary

The Academic Expert Group convened by the Swedish Transport Administration lent its combined experience, expertise, and understanding of global road safety issues, problems, and solutions to create a set of recommendations for a decade of activity by the public and private sectors that would lead to a reduction of worldwide road deaths by one-half by 2030. The recommendations are made in the context of a Third High-Level Conference on Global Road Safety to be held in Stockholm in February 2020 and are offered for consideration by conference participants and leaders from businesses, corporations, governments, and civil society worldwide.

The report reflects on the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020, addressing both its accomplishments and limitations. The targeted reductions in global road deaths were not achieved, and in fact the number of global road traffic deaths increased over the decade. Available data are insufficient to assess progress on serious injuries. However, there were many foundational accomplishments during the decade, including increased awareness of road safety problems and solutions among governments, corporations, businesses, and civil society; measurable and effective safety improvements in many locations; new funding; and new partnerships. Road safety needs were expressed in a new structure using five pillars, and evidence-based interventions were identified for each pillar, along with measures and targets. A significant achievement of the Decade of Action 2011–2020 was the inclusion of road safety among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Integrating a road safety target into SDG 3.6 and 11.2 was a remarkable accomplishment with far-reaching potential.

The report proposes a vision for the evolution of road safety and recommends a new target of 50% reduction in road deaths and serious injuries by 2030 based on expanded application of the five pillars, adoption of Safe System principles, and integration of road safety among the Sustainable Development Goals. The vision describes an evolution of road safety, building from the foundation of the pillars, incorporating adoption of the Safe System approach, and leading to a future comprehensive integration of road safety activity in policy-making and the daily operations of governments, businesses, and corporations through their entire value chains. The vision also stresses the need for further engagement of the public and private sectors and civil society in road safety activities and capacity-building among road safety professionals worldwide.

A set of nine recommendations are proposed to realize the vision over the coming decade:

Sustainable Practices and Reporting: including road safety interventions across sectors as part of SDG contributions | Safe Vehicles Across the Globe: adopting a minimum set of safety standards for motor vehicles |

Procurement: utilizing the buying power of public and private organizations across their value chains | Zero Speeding: protecting road users from crash forces beyond the limits of human injury tolerance |

Modal Shift: moving from personal motor vehicles toward safer and more active forms of mobility | 30 km/h: mandating a 30 km/h speed limit in urban areas to prevent serious injuries and deaths to vulnerable road users when human errors occur |

Child and Youth Health: encouraging active mobility by building safer roads and walkways | Technology: bringing the benefits of safer vehicles and infrastructure to low- and middle-income countries |

Infrastructure: realizing the value of Safe System design as quickly as possible |

Preamble

In 2018, as the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 was nearing its conclusion, the Government of Sweden made an offer to host the Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety, an event that will gather road safety experts and national delegates from around the world to reflect on the purpose, progress, and future of this global road safety movement. As a leader in both road safety theory and practice, Sweden is well-positioned to host this important gathering and provide a structure and forum where stakeholders look back at how the global effort started, take stock in how far we have come, and consider our path forward.

Recognizing the pivotal role that this conference will serve in global road safety and the range of stakeholders engaged in the movement, the Government of Sweden worked closely with UN colleagues to create an inclusive conference planning structure that engaged leaders from governments, non-government and civic organizations, academia, and businesses. Work groups were formed, research was reviewed, and perspectives on the past and future of road safety were compared in order to formulate a framework for the Third Ministerial Conference.

The work of these groups was further motivated by the Political Declaration from the Sustainable Development Goals Summit taking place on September 24–25, 2019 which reaffirmed commitment to implementing the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development and called for accelerated action by all stakeholders at all levels to fulfill this vision (United Nations 2019).

Among the work groups engaged in conference planning was the Academic Expert Group consisting of experienced road safety researchers, practitioners, and thought leaders from around the world. The Academic Expert Group was charged with these primary tasks:

-

What are the results of the Decade of Action, and what experiences can we draw from the efforts made during the past 10 years?

-

What is a challenging and usable target (or targets) for the next 10 years up to 2030 that can be integrated in the 2030 Agenda, in particular Goal 3.6?

-

What processes and tools could be further developed or added to make actions even more effective, and which sectors of the society could be further stimulated to contribute to the overall results?

-

How can trade, occupational safety, standards, corporate behavior, and other aspects of the modern society be linked with road safety?

-

How can nations, local authorities, and governments as well as public and private enterprises, in particular major enterprises, be stimulated to contribute to road safety through their own operations?

-

How can other important challenges, in particular those targeted in Agenda 2030, contribute to improved road safety, and vice versa?

This report documents the recommendations of the Academic Expert Group and provides an indication of the rationale behind their views. A list of the members of the Group is included in the appendix.

Reflections on the Decade of Action 2011–2020

Origins of the Decade

General Assembly Resolution 58/289 of April 2004 recognized the need for the UN System to support efforts to address the global road safety crisis. The Resolution invited the World Health Organization to coordinate road safety issues within the UN System, working in close cooperation with the UN Regional Commissions. The UN Road Safety Collaboration was established, bringing together international organizations, governments, non-government organizations, foundations, and private sector entities to coordinate effective responses to road safety.

The Commission for Global Road Safety formed by the FIA Foundation in 2006 issued a call for a Decade of Action for Road Safety in its 2009 report which was widely endorsed. The UN Secretary-General, in his 2009 report to the General Assembly, encouraged Member States to support efforts to establish a Decade as a means to coordinate activities in support of regional, national, and local road safety, accelerate investment in low- and middle-income nations, and rethink the relationship between roads and people.

In March 2010 the UN General Assembly proclaimed the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 with a goal of stabilizing and then reducing the forecasted level of road fatalities and injuries around the world. The resolution requested that the World Health Organization and the UN Regional Commissions, in cooperation with partners in the UN Road Safety Collaboration and other stakeholders, prepare a global plan with the Decade as a guiding document to support the implementation of its objectives.

Major Milestones and Accomplishments

The Decade of Action raised global awareness of road safety among governments, businesses, and civil society. It brought measurable and effective safety improvements. It attracted new funding and new partnerships and brought road safety closer to the global arena of public health issues.

Target setting is now common practice across sectors of society as a means for managing progress toward ambitious goals, and in some cases the practice has developed from simple targets to complex sets of sub-targets, indicators, and action plans. However, there is room for improvement in road safety indicators to ensure an adequate link to outcomes so they can be useful in guiding policy decisions.

A significant achievement of the Decade of Action with regard to the long-term course of road safety is the inclusion of road safety among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Integrating road safety targets 3.6 and 11.2 in the SDGs was a remarkable accomplishment with far-reaching implications. The 2030 Agenda states clearly that the “17 Sustainable Development Goals with 169 associated targets are integrated and indivisible.” This recognition places road safety at the same level of criticality as other global sustainability needs and clearly indicates that sustainable health and well-being cannot be achieved without substantial reductions in road deaths and serious injuries. While this integration with other SDGs has yet to be realized on a global level, the opportunity for new partnerships is now available, and the potential benefits that could come from such integration are compelling.

According to the projections for road deaths and the ambition set by the Decade of Action in 2011, deaths were expected to reach 1.9 million by 2020 if no actions were taken. The ambition was to “stabilize and then reduce deaths” by about 50% of the forecast level, or approximately 900,000 deaths, by 2020. The road safety target included in the SDGs uses different definitions and data sources and calls for an ambitious 50% reduction in the absolute number of global deaths and injuries between 2015 and 2020, or about 650,000 deaths.

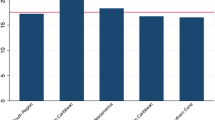

The 2018 Global Status Report estimates a current level of about 1.35 million road deaths, indicating that the ambition of stabilizing the trend of global deaths has not been met. Data on injuries are insufficient to measure progress. The targeted numbers of annual deaths – neither the 900,000 proposed by the original Decade nor the 650,000 included in the later SDG – are likely to be reached by 2020 (Fig. 1).

A significant achievement was the establishment of the UN Special Envoy for Road Safety. This position, created by the UN Secretary-General in April 2015, signifies the importance of road safety among global needs and provides a focal point for promoting and coordinating road safety activities among government and non-government organizations worldwide.

A particularly visible element of the Decade are the road safety pillars. This pillar structure illustrates the scope of activities needed to achieve lasting road safety progress and has proven to be useful for identifying gaps in national programs and allocating local resources to the most critical areas for improvements. The individual interventions included under each of the five pillars have been tested and evaluated and provide an evidence-based pathway to sustainable road safety. Evaluations of these interventions has been collected in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and their application has been facilitated by the development of calculator tools that can estimate impacts of changes and assist implementers in making strategy and investment decisions (Elvik et al. 2009; Wismans et al. 2019).

The road safety pillars are expected to remain the primary tools for improving road safety in the coming decade. The challenge is in expanding their adoption and application, building upon this achievement with the Safe System approach and integrating safety across sectors. The Sustainable Development Goals offer an opportunity to achieve these objectives.

Vision for the Second Decade

Road safety is integral to nearly every aspect of daily life around the globe. We step from our homes into a road system that leads us to work, to get our food, and to many of our daily family, health, and social needs.

The influence of the road transportation system is so pervasive that its safety – or lack of safety – affects a wide range of social needs. Road safety – mobility without risk of death or injury – affects health, poverty, equity, the environment, employment, education, gender equality, and the sustainability of communities. In fact, road safety directly or indirectly influences many of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Unlike other modes of transportation such as aviation, railways, or maritime, road transport has lacked an integrated and comprehensive approach towards safety. The Academic Expert Group proposes a global road safety vision that describes how existing accomplishments combined with progressive techniques can lead to a new era in which road safety is integrated in a range of other social development movements and pursued in a comprehensive manner.

The vision proposes an evolution of road safety beginning with the road safety pillars as a foundation. Nations at every level of road safety development rely on fundamental tools included among the pillars as the operational elements to achieve and maintain high levels of road safety.

Many nations around the world have enhanced the effect of pillar interventions by applying them selectively and strategically according to Safe System principles. The Safe System approach addresses problems closer to their root cause and on a broader scale than conventional methods.

The highest level of road safety evolution has yet to be reached by any nation but promises exponential benefits. At this level, road safety is no longer an independent public health and safety initiative, but rather an integral part of a broad range of societal endeavors from commercial enterprise to humanitarian initiatives (Fig. 2).

Strengthened Road Safety Pillars

While there is still much to learn, we have the tools to vastly improve road safety around the globe. The five road safety pillars identified in the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 include a set of evidence-based interventions that can measurably improve the safety of road traffic, especially if they are applied with the Safe System approach. These road safety pillars include tools for improving road safety management and enhancing the safety of roads and mobility, vehicles, road users, and emergency response.

We have made progress in getting these tools into practice. What we need is much more progress, the sort of progress that will require a larger and more effective army of implementers. The Sustainable Development Goals – and the army of advocates who are advancing these goals around the world – can make a substantial contribution to this need.

Safe System Approach

The vision for the next decade multiplies the reach and impact of the tools within the five pillars and also extends the value of another critical component of the first decade, the Safe System approach. The vision recognizes that the tools of the five pillars will have the greatest effect on safety when they are applied alongside new tools in a strategic and pervasive manner following the proven principles of the Safe System approach. The Safe System approach – also referred to as Vision Zero – recognizes that road transport is a complex system and that humans, vehicles, and the road infrastructure must interact in a way that ensures a high level of safety. The Safe System approach (Welle et al. 2018):

-

1.

Seeks a transportation system that anticipates and accommodates human errors and prevents consequent death or serious injury

-

2.

Incorporates road and vehicle designs that limit crash forces to levels that are within human tolerance

-

3.

Motivates those who design and maintain the roads, manufacture vehicles, and administer safety programs to share responsibility for safety with road users, so that when a crash occurs, remedies are sought throughout the system, rather than solely blaming the driver or other road users

-

4.

Pursues a commitment to proactive improvement of roads and vehicles so that the entire system is made safe rather than just locations or situations where crashes last occurred

-

5.

Adheres to the underlying premise that the transportation system should produce zero deaths or serious injuries and that safety should not be compromised for the sake of other factors such as cost or the desire for shorter transportation times

Integration of Road Safety in Sustainable Development Goals

As an independent endeavor, the road safety movement is limited in potential reach and influence. Positioned as a special interest, road safety is often subordinate to other social needs and can gain progress only where it can achieve attention by road users or those who make decisions about roads and vehicles. But if recognized as a basic necessity that can facilitate progress in meeting social needs ranging from gender equity to environmental sustainability, the potential of road safety can be greatly expanded.

Among the key achievements of the Decade of Action 2011–2020 was the inclusion of road safety in the Sustainable Development Goals. Because these Goals are defined as indivisible and mutually dependent (United Nations 2015), the explicit citation of road safety in the Health and Well-Being and Sustainable Cities goals is accompanied by implicit integration across the goals and especially in those addressing climate, equity, education, and employment.

Integrating road safety among the Sustainable Development Goals is an important step toward embedding road safety expectations and activities in the far-ranging daily processes of governments and in the operations of corporations, businesses, and civic organizations globally. Substantial levels of such widespread integration have yet to be achieved but have the potential to expand interventions to a scale where road deaths and serious injuries would be reduced to near zero.

Importance of the Vision for Low- and Middle-Income Nations

The focus of global road safety efforts needs to remain on low- and middle-income nations, the location of the great majority of the problem – 93% worldwide road traffic deaths in 2016.

The Academic Expert Group believes that the value of the road safety pillars is universal.

That is, the scope of action described by the pillars – Road Safety Management, Infrastructure, Safe Vehicles, Road User Behavior, and Post-Crash Care – is essential in any environment, and the activities outlined in the Global Plan of Action (World Health Organization 2010) for each pillar can be effective in nearly every national context.

However, the Group recognizes that implementation of these activities from the Safe System perspective in some environments can face formidable barriers. Competing priorities, the capacity of local governments to take action, and differences in geographic, geopolitical, and geodemographic situations can present serious challenges to implementing changes necessary to initiate or sustain road safety improvements. These challenges have likely contributed to the lack of reductions in road deaths over the past several years in many nations.

Despite these challenges, many nations have made progress with key road safety activities. Since 2014, 22 nations with a combined population of over 1 billion people – 14% of the world population – have amended laws on one or more key risk factors, bringing their legislation in line with best practice (World Health Organization 2018a). Credit for this progress likely goes to a range of influencers, including motivated local government or non-government leaders, actions by national or international NGOs with interest in road safety, and leadership through the UN system.

Change in low- and middle-income nations has been slower, and governments in these nations need to take a deeper look at their situation and address this issue, with help from external partners as the situation requires. While the Agenda 2030 looks to governments for lead responsibility, strong and sustained efforts from the private sector are important for the achievement of the goals and targets. Business underlies 84% of the GDP and 90% of the jobs in developing countries and, by utilizing their full value chains, can make a substantial contribution to the safety of those who are at greatest risk for a range of threats including motor vehicle crashes.

The Safe System approach is of critical importance not only for developed areas but also for developing nations and cities. The global trend toward urbanization will cause widespread expansion of cities and create new urban areas in coming decades. The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs predicts that urban areas will grow by more than 50% over the coming 30 years, with the great majority of this expansion occurring in Africa and Asia (World Urbanization Prospects 2018). New roads and infrastructure will be necessary to accommodate the urban expansion, and this creates an opportunity to incorporate Safe System design features from the beginning.

Technological development will continue to accelerate making existing safety devices more affordable and introducing new safety potential for vehicles and the road infrastructure. Public and private sector organizations will be increasingly compelled to contribute to sustainability goals, including road safety. The vision presented here by the Academic Expert Group provides an opportunity to guide these changes in ways that can improve road safety and contribute to global sustainability.

Sustainable Development Goals

The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all Member States in 2015, provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. The Agenda is based on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and presented as an urgent call to action for both the public and private sectors in a global partnership.

The SDGs cover a range of necessities for improving and stabilizing both the human condition and the condition of our planet, recognizing the interdependence of these two objectives (Fig. 3).

The SDGs build on decades of research, deliberation, and negotiation. Transportation issues have been part of the sustainability discussion for at least 30 years, initially with a focus on reducing congestion and improving energy efficiency. However, road safety was not explicitly included among the development goals and targets until adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015.

Sustainable Development Goals: Integrated and Indivisible

The UN General Assembly Resolution 70/1, Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, defines a global vision of unprecedented scope, far beyond the previous Millennium Development Goals. It maintains a focus on priorities such as poverty eradication, health, education, and food security and nutrition, while adding critical economic, social, and environmental objectives.

The specific inclusion of road safety targets in Agenda 2030 reflects universal recognition that death and injury from road crashes are now among the most serious threats to the future of our people and planet. Article 55 of the Resolution states that the 17 Goals are “integrated and indivisible, global in nature and universally applicable.” This means that road safety is no longer a need that can be compromised or traded off in order to achieve other social needs. It implies, for example, that the safety risks inherent in raising speed limits should not be tolerated in order to realize economic benefits of faster traffic and that investments necessary to improve road safety should not be diverted for other needs.

The 2030 Agenda also points out the deep interconnections among the goals and targets, beginning with the fundamental interconnection of the health of people and the health of the planet and extending to many other interdependencies (Fig. 4).

An analysis of SDG interactions at the Goal level by the International Council for Science (2017) points out the connections between Goal 3: Good Health and Well-Being, the location of the primary road safety target, and many of the other Goals.

Together, these qualities of indivisibility and connectedness among the goals and targets present an opportunity to advance road safety in new context, but they need to be pursued and acted upon by the road safety community and others. They need to be translated into actions and solutions to contribute to improving road safety and other human development issues worldwide.

Agenda 2030 compels public and private organizations of all sizes to apply their resources and influence to the widest extent possible toward achievement of SDGs. Many organizations, government and corporate, have a health or safety mandate that will lead them to apply resources directly to targets 3.6 and 11.2. A far greater range of entities have mandates that point them directly at one or more other Goals and – because of the interconnectedness and indivisibility of the Goals – will also recognize the relevance of applying their influence to advance road safety. Examples of these connections include:

-

Environmental organizations contributing to efforts to reduce vehicle speeds and lower emissions and noise

-

Gender equity organizations contributing to safe pedestrian, bicycle, and motor vehicle travel as a means to open opportunities for women of all ages

-

Workplace safety organizations contributing to road safety as a leading cause of workplace death and injury

-

Organizations pursuing eradication of poverty advancing road safety as a means for improving access to employment opportunities

-

Education organizations promoting road safety to facilitate travel to local schools

-

Organizations seeking elimination of inequalities supporting road safety to encourage access to essential needs for individuals and under-served communities

Strategies and Tools for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals

Government and corporate organizations need guidance and direction to make meaningful contributions to a range of SDGs. Following are examples of tools and guidance available to assist organizations in focusing their efforts to make efficient and effective contributions.

In their Sustainable Development Report: 2019, Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network propose a set of six transformation strategies that can be used by governments and corporations to organize their SDG contributions. These transformation strategies are structured to take advantage of synergies among the SDGs and to align with typical methods of government and corporate operations (Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network 2019).

Sustainable Mobility for All is advancing sustainable mobility as a prerequisite for achieving a range of SDGs. The organization is engaging stakeholders to develop a Global Roadmap for Action to promote four mobility policy goals, Universal Access, Efficiency, Safety, and Green Mobility, and offers tools such as Mobility Data by Country, a Global Mobility Tracking Framework, and Global Transport Stakeholder Mapping (Sustainable Mobility for All 2019).

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) works with cities and corporations to facilitate their effective and efficient contribution to the SDGs. WBCSD is a CEO-led global membership organization representing nearly 200 leading businesses. WBCSD enhances the business case for sustainability with tools, models, services, and experiences (World Business Council for Sustainable Development 2019).

The Sustainable Development Compass provides practical guidance for companies to align their strategies and measure their contributions to the SDGs. Developed through a partnership among GRI, the UN Global Compact, and WBCSD, the Sustainable Development Compass assists companies in understanding the SDGs, defining priorities, settings goals, integrating activities, and reporting and communicating progress (Sustainable Development Compass 2015).

Finally, while sources of guidance and tools such as those described above can help engage businesses, governments, and civil organizations in effective contributions to the SDGs, and assist them in focusing, coordinating, monitoring, and measuring their work, there are currently few such tools available to guide road safety contributions. This type of road safety guidance is urgently needed.

This guidance for corporate and government organizations needs to address where contributions can be made to road safety as well as how such actions can be taken. The ground-level activities needed to contribute to the road safety targets 3.6 and 11.2 are well understood and documented. The five pillars described in the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 include a comprehensive set of evidence-based interventions that have proven effective in some circumstances and will provide a useful basis for new road safety contributions by governments, corporations, and civil society, especially if applied according to Safe System principles (Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2010).

Prerequisites for Change

Expanded Engagement of Public and Private Sectors

In the coming decade, we have the potential to use the linkages between road safety and the Sustainable Development Goals to expand the reach of our tools well beyond the traditional scope of transportation, public safety, and public health. Integrating road safety among a range of Sustainable Development Goals will engage non-traditional public and private stakeholders and lead to road safety activities taking place across entire governmental and corporate value chains.

Governments, corporations, and civil society will be encouraged to use their resources and influence to contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals wherever possible. The collective power of public and private organizations around the world adopting road safety practices as part of their contributions to the Sustainable Development goals, together with their endorsement, leadership, and purchase power, is substantial. This potential multiplies the value of the road safety pillars, placing these tools in the hands of a far wider group of motivated implementers than has previously been possible.

Corporations from every sector and public authorities with a wide range of direct responsibilities can be engaged in road safety activities. These organizations will be motivated to look beyond their core tasks for efficient and effective strategies to contribute to the SDGs. If these organizations are educated concerning the need and opportunities, road safety actions could be a widespread priority.

The means for contributing to road safety by these new partners could include policies regarding vehicle fleet purchase and the manner in which these vehicles are scheduled, routed, and driven. In addition, these organizations can use their contractual and procurement power to affect road safety policies and practices of all those upstream organizations from which they purchase services and supplies and all those downstream to whom they distribute their services.

Methods to realize the full potential of corporate and government engagement in road safety have yet to be fully explored. Combinations of traditional government-corporate regulatory roles may be effective alongside government incentives and voluntary SDG-driven roles. Exploration and evaluation of such alternative combinations of governmental and corporate initiatives is a high priority.

Capacity-Building

Research shows that a strong road safety management system is correlated with good road safety performance. The World Report on the Prevention of Road Traffic Injuries (2004) points out two key elements of a strong road safety management system, an effective lead road safety agency and committed road safety leadership.

The World Report defines a lead agency as an organization with the authority and responsibility to make decisions, control resources, and coordinate efforts by all sectors of government, including those of health, transport, education, and the police. The Report describes road safety leadership as including the capacity for commitment and informed decision-making at all levels of government, the private sector, civil society, and international agencies to support the actions necessary to achieve reductions in road risks, deaths, and serious injuries.

While a top-down approach to road safety management incorporating a lead agency and good safety leadership is an important ingredient, examinations of high-performing national road safety programs also point out the need for committed and knowledgeable road safety professionals. High-performing professionals are not only good practitioners (able to design and implement effective interventions) but also are able to link themselves with top-level decision-making in order to create a positive political environment and scale up effective road safety interventions. In some countries, road safety professionals are able to influence public and political discourse on road safety, and this has paved the way for effective policies (Bliss and Breen 2009).

However, many road safety professionals lack the skills necessary to be good practitioners, and an even greater number lack the insights needed to recognize opportunities to influence top-level road safety decision-making in the public and private sectors.

This lack of capacity among road safety professionals is a major barrier to progress in many countries. These countries do not have professionals with the specialized knowledge necessary to be effective in making roads and vehicles safer, to achieve safer road user behavior, and to design and operate a well-functioning post-crash system. Further, many countries and cities do not have the expertise required to adapt Safe System principles to their own conditions, effectively collect and analyze road safety data, or carry out quality road safety research. While less information is available to generalize the adequacy of such road safety professional expertise in the private sector, it is very likely that similar deficiencies exist.

Capacity-building for road safety professionals working for the government, the private sector, civil society, and research institutions should be given top priority, not only to make them better practitioners but also to prepare them to act more effectively within their organizational and national structures. Such capacity-building could go a long way toward moving road safety higher on the political agenda and advancing the evolution of road safety programs in jurisdictions and corporations. Study of road safety capacity-building approaches should be conducted to identify effective techniques and strategies.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are offered by the Academic Expert Group for inclusion in the Stockholm Declaration and for use by political, corporate, and civil society leaders and practitioners worldwide. The recommendations are directed towards 2030 and are intended to build upon those previously established in the Moscow Declaration of 2009 and the Brasilia Declaration of 2015 as well as prior UN General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions. The Academic Expert Group considers these additional recommendations to be essential for achieving the goal of reducing global road fatalities and serious injuries by half by 2030. The recommendations are interrelated and intended to be considered as a set rather than as individual options. The recommendations are based on the Safe System Approach.

These recommendations are necessarily far-reaching in both scope and ambition. The Group believes that the best strategy for reaching the goal for 2030 is to maintain commitment to prior recommendations and immediately initiate action on each of these new recommendations with sufficient intensity to achieve substantial progress by the middle of the coming decade. The Group further recommends that a rigorous evaluation be conducted 5 years into their adoption to measure progress and that the findings be used subsequently to refine and adjust the strategy.

Recommended Target for 2030

The Academic Expert Group discussed the importance of target setting and recognized the action taken by the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development to “maintain the integrity of the 2030 Agenda, including by ensuring ambitious and continuous action on the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals with a 2020 timeline (United Nations 2019).”

The Group recommends the following points:

It is crucial that a specific road safety target is maintained and kept up to date within the Sustainable Development Goals.

Proposed wording for Sustainable Development Goal 3, Target 3.6:

Between 2020 and 2030, halve the number of global deaths and serious injuries from road traffic crashes, achieving continuous progress through the application of the Safe System approach.

The Academic Expert Group further recommends that:

Operational targets should be set by individual global regions (consistent with the ambition of 3.6, but taking into account local developments, conditions, and resources).

Targets should include fatalities and serious injuries. Identifying appropriate rates of deaths and serious injuries is also desirable. However, the optimal measure of fatal and non-fatal injury rates has yet to be determined.

Linkages and collaborations should be established among the constituencies associated with the range of other SDGs that are affected by and associated with road safety. These include Quality Education, Decent Work and Economic Growth, Reduced Inequalities, Sustainable Cities and Communities, Climate Action, and others. Actions should involve both the public and private sectors.

Criteria Considered in Formulating Recommendations

To identify areas of focus and specific content of the recommendations, the Academic Expert Group agreed on a number of inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Recommendations that extend beyond Sustainable Development Goal 3.6 and establish synergies with other Goals will be prioritized.

-

2.

Recommendations that engage non-traditional partners with potential for leadership or constituencies that could reach widespread participation will be prioritized.

-

3.

Recommendations must reach beyond those previously established in Declarations from the First and Second Ministerial conferences and Resolutions from intervening UN General Assemblies.

-

4.

Recommendations must have compelling evidence of potential impact in terms of intervention effectiveness, scale of the problem addressed, and efficiency of the proposed solution.

-

5.

Recommendations must adhere to the SMART principle:

-

Specific: identifiable responsibilities and actions

-

Measurable: tangible and observable with objective units of scale

-

Attainable: possible considering known obstacles

-

Relevant: consistent with the Safe System approach

-

Timebound: achievable (or capable of substantial progress) by 2030

-

The Academic Expert Group recommends that additional consideration be given to monitoring progress toward achievement of the recommendations. While useful measurement tools are available, such as the UN Voluntary Global Performance Targets (United Nations 2018a) and their associated indicators (United Nations 2018b), these measures do not adequately reflect implementation of the Safe System approach. More work is needed to develop targets and indicators that reflect Safe System implementation (European Commission 2019).

Recommendation #1: Sustainable Practices and Reporting

Summary

In order to ensure the sustainability of businesses and enterprises of all sizes, and contribute to the achievement of a range of Sustainable Development Goals including those concerning climate, health, and equity, we recommend that these organizations provide annual public sustainability reports including road safety disclosures and that these organizations require the highest level of road safety according to Safe System principles in their internal practices, in policies concerning the health and safety of their employees, and in the processes and policies of the full range of suppliers, distributors, and partners throughout their value chain or production and distribution system.

Rationale

The traditional assumption that road safety is solely the responsibility of governments is being challenged by several factors. First, while some governments have led substantial improvements in road safety in prior decades, relying on government leadership and regulation has not resulted in sufficient progress in recent years in most countries. This shortcoming is despite the launch and growth of a worldwide road safety movement stimulated by the UN Decade for Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 that was largely targeted at engaging and directing government action.

Second, governmental strategies to improve road safety have largely targeted the regulation of individual road user behaviors, missing the opportunity to engage organizations such corporations, businesses, civil society, and other authorities in road safety commitments.

Third, the scale and potential road safety impact of large multinational corporations is larger than that of many governments. Supply chains associated with multinational corporations account for over 80% of global trade and employ one of five workers (Thorlakson et al. 2018).

The World Economic Forum points out that a number of multinational corporations have grown to such a scale that they eclipse most national governments in gross annual revenue (World Economic Forum 2016). Other authors point out that the scope of multinational companies allows far-reaching influence. More than 30 financial institutions have consolidated revenues of more than $50 billion each – more than the gross domestic product of 2/3 of the world’s countries. Beyond their economic power, multinational companies shape social conditions. In developing nations, large corporations may spend more on education than the government (Khanna 2016) (Fig. 5).

Clearly, corporations and businesses have the power and global reach to effectively contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. A number of frameworks, principles, and guidelines have been developed over the past decades to establish expectations concerning their contributions, including:

-

International Labour Organization Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy

-

UN Global Compact Principles

-

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

These principles address responsibilities such as universal rights, environmental concerns, and anti-corruption standards, defining minimum expectations for companies engaging in sustainable development activities. Other guidelines include the ISO 26000 Guidance on Social Responsibility and regional guidance such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (Sustainable Development Compass 2015).

Businesses recognize the value of corporate virtue, and the SDGs provide a timely and widely endorsed opportunity for corporate engagement in sustainability. A review of business trends in the book The Market for Virtue concludes that corporate social responsibility has been a global phenomenon since the 1990s and that the business case for such practices is widely understood and applied. However, the author explores the extent of corporate sustainability practices and suggests that they could go much further (Vogel 2005).

An analysis performed by Oxfam in 2018 (Mhlanga et al. 2018) found mixed evidence of corporate action in responding to the SDG opportunity. An important positive finding is that more companies – especially multinational organizations – are making commitments to the SDGs in their corporate communications. This is an essential step forward; however, evidence concerning increases in corporate action were more difficult to identify.

A large body of evidence supports the benefits of sustainable practices. A review over 200 academic papers on sustainability and corporate performance found that:

-

Ninety percent of the studies find that sound sustainability standards lower the cost of capital of companies,

-

Eighty-eight percent of studies conclude that solid environmental, social and governance practices result in better operational performance, and

-

Eighty percent of studies show that stock price performance is positively correlated with sustainability practices (Clark et al. 2015).

Increasingly, investors are looking beyond solely economic indicators before purchasing a firm’s stock or providing capital. One in four dollars now invested in the USA – a total of $23 trillion/year globally – is now directed to firms after considering their environmental, social, and governance performance (Scott 2019).

Sustainability reporting is key to stimulating corporate change. Reporting that is relevant, reliable, and accessible will help businesses organize and prioritize their efforts, actuate the business case for corporate virtue by enabling meaningful external review, and stimulate the application of stakeholder pressure, both positive and negative.

Actions and Responsibilities

Sustainability reporting standards and models are available from a number of sources, including those developed by Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) who report widespread use of their standards among the world’s largest corporations (GRI and Sustainability Reporting 2019).

Existing literature provides little detail on how to report on road safety in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. Further work is needed to facilitate this reporting task. Because organizations differ in the ways they can affect sustainability, including their opportunities to improve road safety, reporting standards should be specific to the functions of the organization. For example, opportunities for sustainability contributions by a manufacturing firm that uses trucks to bring in raw materials and distribute products will be far different than a banking organization that performs its transactions electronically. Specific standards for several industrial sectors are now being developed by GRI. To fully reflect road safety sustainability actions across the range of public and private sector organizations, many more such targeted reporting standards – including standards for road safety reporting – are needed.

With regard to road safety targets 3.6 and 11.2, reporting should be internal and external and extend across the full range of the corporate value chain. A value chain is the full scope of activities – including design, production, marketing, and distribution – businesses conduct to bring a product or service from conception to delivery. For companies that produce goods, the value chain starts with accessing raw materials used to make their products and includes every other step including distribution and use by purchasers (Harrison 2018).

Author Michael Porter from Harvard Business School was the first to discuss the concept of a value chain and how it can be used to identify opportunities and focus energy to increase corporate value. Porter points out five primary activities in a corporate value chain (Porter 1998):

-

Inbound logistics are the receiving, storing, and distributing of raw materials used in the production process.

-

Operations is the stage at which the raw materials are turned into the final product.

-

Outbound logistics are the distribution of the final product to consumers.

-

Marketing and sales include advertising, promotions, sales-force organization, distribution channels, pricing, and managing the final product to ensure it is targeted to the appropriate consumer groups.

-

Service refers to the activities needed to maintain the product’s performance after it has been produced, including installation, training, maintenance, repair, warranty, and after-sale services.

While specific opportunities will vary, nearly every business, corporation, or government organization could contribute and report on road safety across their value chain. Using Porter’s model, the following table illustrates a number of possibilities:

Inbound logistics | Operations | Outbound logistics | Marketing and sales | Service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vehicle manufacturer | Require component suppliers to follow a road safety management program (e.g., ISO 39001) | Advance safe design at every opportunity including speed limiters and driver impairment detection | Require distribution carriers to follow safest routes to dealerships and that professional drivers comply with safety rules | Provide vehicles with at least the UN-recommended eight minimum safety standards for every global market | Provide training on use of safety devices and free safety checkups for first and subsequent owners |

Clothing producer | Require textile and garment assembly firms to provide safe transportation to and from the factory for workers | Set expectations and monitor safety performance by contracted trucking operations | Contract only with freight carriers that use an effective safety management program | Promote active and safe mobility with clothing design and in advertising | Design bicycle helmets and offer at reduced cost to clothing customers |

Local government authority | Require procured services to act safely, use safe vehicles, and have a system for safety management | Require employees to choose the safest travel options and practice safe behaviors while traveling on duty | Ensure that shipping is performed by services that comply with safety requirements | Publish safety performance and results openly | Advise citizens on safe travel options, such as safe routes to school |

Insurance company | Require facilities, advertising or other service providers to follow a road safety management program | Purchase only vehicles with highest NCAP ratings for corporate fleet | Reduce unnecessary travel with electronic communications | Reward safe driving by insured using voluntary speed monitoring systems | As part of basic service, provide safety devices such as bicycle helmets and child safety seats to customers |

Mobility service provider | Ensure that navigation maps are produced with boundary conditions reflecting safety and environmental needs | Use only vehicles with the highest NCAP score and minimal CO2 and noise impact | Use geofencing to make sure delivery of services is safe and sustainable | Publish safety & environmental impact of the service | Advise citizens on safe service options, such as selection of safe routes |

Beyond direct control of their value chain, large corporations and non-government organizations also have political influence. A number of authors have suggested that sustainability reporting also addresses corporate political activities that are relevant to the achievement of the SDGs. National policies and regulation are critical for driving SDG achievement, and corporate engagement in the political and legislative process is an important influence on such rules (Lyon et al. 2018; Vogel 2005).

Finally, while corporate action and reporting are vital for road safety and the full range of SDGs, the same applies to governments, who have primary responsibility for review of SDG progress and follow-up. Governments at every level can report on sustainability actions in their own operations and, through their governance practices, can influence reporting by the private and non-profit sectors. The UN High-Level Political Forum for the 2030 Agenda provides a mechanism for countries to submit Voluntary National Reviews. Conducting such reviews is an important indicator of political commitment and is also likely to influence the quantity and quality of corporate reporting.

Between 2016 and 2018, 111 of the 193 Member Nations submitted Voluntary National Reviews, with an additional 73 Reviews scheduled to be presented in 2019 and 2020. Nearly all countries with populations greater than 100 million have submitted or plan to submit a Review by 2020. Together these countries represent more than 90% of the global population and large shares of economic and trade activities.

While the UN provides guidelines for the preparation of Voluntary National Reviews, the scope and depth of those submitted vary greatly in terms of institutional mechanisms for conducting the review, participation of non-government organizations, and the use of data and statistics to measure progress (HLPF 2018). More uniform quality and consistency in these Reviews could improve their impact.

This Recommendation Is Linked to Others Including

Procurement, Modal Shift, Child and Youth Health, Zero Speeding, 30 km/h, and Technology.

Recommendation #2: Procurement

Summary

In order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals addressing road safety, health, climate, equity, and education, we recommend that all tiers of government and the private sector prioritize road safety following the Safe System approach in all decisions, including the specification of safety in their procurement of fleet vehicles and transport services, in requirements for safety in road infrastructure investments, and in policies that incentivize safe operation of public transit and commercial vehicles.

Rationale

Corporations, businesses, and government organizations have tremendous influence on society through a range of factors, from political influence to the nature of their products and services. A substantial component of this influence is by means of their spending on the goods and services necessary for their function.

Government procurement is estimated to be 10–15% of gross domestic product on average (World Trade Organization 2019), with some analyses showing that the GDP portion of public procurement in low-income nations is slightly higher than that in high-income countries (Djankov and Saliola 2016). The World Bank reports a total global GDP of about 86 trillion US dollars in 2018 (World Bank Group 2019), with low- and middle-income nations contributing about $32 trillion of that total.

With total corporate procurement spending estimated at an average of 43% of revenues (Schannon et al. 2016) and the revenue of the 500 largest companies totaling $30 trillion (Ventura 2019), the aggregate public and private procurement sums are very large indeed. The social influence of this spending – if directed to incentivize sustainable practices and investments, including road safety – is substantial.

Both government and corporate spending is directed to a value chain – the full scope of activities to bring a product or service from conception to delivery. For companies that produce goods, the value chain starts with accessing raw materials used to make their products and includes every other step including distribution and use by purchasers. Corporate and government services have similar value chains, including the tools, materials, and contracted services needed to conduct and disseminate their function.

When a government controls the safety behaviors of individuals, the burden of enforcement is on the government, and as a result there are certain tolerance levels and inconsistencies in compliance. But when a government deals with a provider of goods or services, and road safety is an integral part of the contract, the burden of enforcement is delegated to the provider. The firm that is supplying the goods or services is motivated to keep the contract and compelled to comply with its terms. Thus, it is important that businesses contracted in public procurement demonstrate capability to comply with safety standards, including having a system to monitor and correct incidents of non-compliance. This example of governance decentralizes monitoring of road safety compliance and can lead to widespread culture change.

Actions and Responsibilities

Each expenditure across the value chain could be used to improve road safety. For example, contingencies could be placed on procurements based on suppliers’ policies or performance with regard to (Bidasca and Townsend 2015):

-

Specifications for vehicle safety levels, including powered two-wheelers, to be used in carrying out procured services. These specifications could go well beyond minimum levels required by domestic governments, to include advanced safety technologies such as speed limiters and impairment detection systems, and could also set limits on vehicle age. In some countries, vehicles owned by businesses and corporations comprise more than half of total vehicle registrations, so the reach of such contingencies could be substantial.

-

Requirements for training of drivers involved in performing procured services, including those who ride powered two-wheelers and other motorized personal mobility devices, in addition to traffic codes and appropriate extreme condition driving skills, such training could involve education regarding fatigue, distraction, speed, impairment, and other safety factors.

-

Expectations for road safety monitoring, reporting, and performance. These expectations could require that firms receiving contracts demonstrate higher-than-average performance across their fleet in terms of crash involvement and traffic citations.

-

Standards for scheduling and planning procured driving operations. These could include practices to manage driver fatigue, use of low-risk roads, use of lower-risk vehicles, and improved times for travel.

Standards and recommended practices for these safety practices and for overall corporate road safety risk management are available from a number of sources including the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2012).

Prioritizing road safety in procurement practices of corporations and governments could have far-reaching effects. Businesses underlie 84% of the GDP and 90% of the jobs in developing countries, and, by utilizing their full value chains, they can improve the lives of those who are at greatest risk for a range of threats including motor vehicle crashes (Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network 2019).

When making decisions about using procurement to improve road safety, corporations and governments should keep Safe Systems principles in mind. Contingencies placed on procurements will have the greatest long-term effects if they are designed to accommodate predictable human errors and create an environment where crash forces are limited to human injury tolerances.

Safe System principles would favor vehicle safety requirements that accommodate driver errors, such as electronic stability control and automatic emergency braking, and devices that could reduce crash forces, such as intelligent speed adaptation. Other Safe System procurement strategies could include requirements that contracted services use routes with good road design including separated pedestrian and bicycling facilities, roundabouts, road diets, and traffic calming to reduce speeds around vulnerable road users.

This Recommendation Is Linked to Others Including

Sustainable Practices and Reporting, Modal Shift, Safe Vehicles, Zero Speeding, 30 km/h, Technology, and Infrastructure.

Recommendation #3: Modal Shift

Summary

In order to achieve sustainability in global safety, health, and environment, we recommend that nations and cities use urban and transport planning along with mobility policies to shift travel toward cleaner, safer, and affordable modes incorporating higher levels of physical activity such as walking, bicycling, and use of public transit.

Rationale

Evidence points to the widespread value of decreasing dependence on personal motor vehicles for transport and increasing use of safer, cleaner, and healthier alternatives. According to the World Health Organization, insufficient physical activity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality and is on the rise in many countries, adding to the burden of non-communicable diseases and affecting general health worldwide (World Health Organization 2011). Active travel can help prevent many of the 3.2 million deaths from physical inactivity, 2.6 million of which are in low- and middle-income nations.

The burden of insufficient physical activity is particularly severe for the younger population. The most recent estimates indicate that 81% of adolescents aged 11–17 years do not meet the WHO’s Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Physical inactivity is estimated to cost more than $50 billion US annually in increased healthcare expenditures (Ding et al. 2016) or about 2–3% of national healthcare expenditures in high-, middle-, and low-income nations (Bull et al. 2017).

A critical prerequisite to modal shifts is safe environments for walking and biking and low-speed powered two- or three-wheelers. Evidence from developed countries ranks biking and walking among the least safe modes of transportation (ETSC 2019).

In our current environment, shifting individual trips from automobiles to walking or bicycling is often considered in terms of a trade-off between safety and health. For example, a systematic review conducted by the EU-funded PASTA (Physical Activity through Sustainable Transport Approaches) Project examined 30 independent analyses of the health impact of active mobility and found that the health benefits of increased physical activity far outweighed increases in safety and health risks associated with walking or bicycling. These results were consistent across analysis methodologies and geographic areas involved (Mueller et al. 2015) (Fig. 6).

Health determinant contribution to the estimated health impact of mode shift scenarios to active mobility (Mueller et al. 2015)

However, in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, safety and health should not be traded off against one another. Consistent with the principle that the Sustainable Development Goals are integrated and indivisible, priority should be given to actions that will allow improvements to both safety and health. The risks associated with pedestrian and bicycle travel are correctable by redesigning walkways and bicycle pathways to separate these modes from traffic moving at greater than 30 km/h and by providing better lighting and safer street crossings (Fig. 7).

Actions and Responsibilities

The WHO Global Action Plan on Physical Activity points out that policies that promote compact urban design and prioritize access by pedestrians, cyclists, and users of public transport can reduce use of personal motorized transportation, carbon emissions, and traffic congestion as well as healthcare costs while stimulating the economy in local neighborhoods and improving health, community well-being, and quality of life (World Health Organization 2018b). Improved infrastructure, both physical and digital, could improve the availability and safety of shared micro-mobility options such as e-scooters and e-boards.

In addition to eliminating risks to pedestrians and cyclists from motor vehicle traffic, crime needs to be controlled to improve perceptions of security. A number of studies have documented the association between perceived personal safety and frequency of walking or bicycling. A study of attitudes and walking habits in 8 European cities showed that the odds of occasional walking were 22% higher among women and 39% higher among men who perceived their neighborhood as being safe (Shenassa et al. 2006). Similar findings were reported from a study in Nigeria which measured frequency of physical activity and found that women were far more affected by both traffic and crime perceptions than men (Oyeyemi et al. 2012).

The Global Action Plan on Physical Activity also indicates that beyond their direct effect on road safety and health, safer walking and bicycling routes could contribute to a range of Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 4 (Quality Education), Goal 5 (Gender Equality), Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities), Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), Goal 13 (Climate Action), Goal 15 (Life on Land), and Goal 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Infrastructure investments and policies that improve perceptions of safety, both from traffic and crime, and especially address gender safety concerns, are important prerequisites to encouraging modal shifts to active mobility. Well-maintained sidewalks, walking and bicycling paths that are separated from fast-moving traffic, adequate pedestrian crossing facilities, and effective street lighting are critical safety measures.

The iRAP star rating program for roads has been effective in stimulating investment in road safety. A star rating program specifically for pedestrian and bicycling facilities could be effective in calling attention to the need for safety improvements such as physical separation from fast-moving motorized traffic and safe crossings where necessary. Geofencing (i.e., digital infrastructure to allow only specific vehicle types and speeds in designated geographic areas) could also be effective in reducing pedestrian and bicycling risk.

Policy evaluations have compared a variety of approaches for stimulating modal shifts. A study of experience in four midsize northwest European cities concluded that the greatest modal shift results from a mix of car-constraining “push” strategies along with “pull” policies that encourage alternatives to car transportation (Dijk et al. 2018).

This Recommendation Is Linked to Others Including

Infrastructure, Zero Speeding, 30 km/h, and Child and Youth Health.

Recommendation #4: Child and Youth Health

Summary

In order to protect the lives, security, and well-being of children and youth and ensure the education and sustainability of future generations, we recommend that cities, road authorities, and citizens examine the routes frequently traveled by children to attend school and for other purposes; identify needs, including changes that encourage active modes such as walking and cycling; and incorporate Safe System principles to eliminate risks along these routes.

Rationale

Our children are our most valuable societal asset, and we cannot look into the future without special consideration for their welfare. This principle underlies the development of the UN declaration of children’s rights (United Nations 1989). While mortality among children less than 5 years of age is down over the past decades (World Health Organization 2019), the children of today are the first in history to have a predicted lifespan shorter than that of their parents (World Health Organization 2018b). Recent decreases in overall life expectancy have resulted from other factors, but motor vehicle crash deaths remain the leading cause of death globally for ages 5–29.

Another substantial risk to child health, lack of physical activity, is related to road safety in that the safety of roads affects decisions about when and where children will walk or bicycle. Both road safety and the frequency of physical activity could be improved by a few common measures. Widespread adoption of compact living centers and highly connected neighborhoods that reduce dependence on motor vehicles could facilitate both the frequency and safety of walking and bicycling for daily transportation. This type of physical activity as a regular routine is particularly beneficial to health.

However, the popularity of walking and bicycling is declining in many countries, especially in low- and middle-income nations where large numbers of people are switching from active mobility to personal motorized transport (Li et al. 2017), including scooters or mopeds, which can be driven by those as young as age 14 in many countries.

Two UN human rights conventions in the 1989 Declaration of the Rights of Children, the Right of Protection from Abuse and Neglect and the Right to Guidance from Caring Adults, have underpinned child safety legislation around the world, including child passenger safety laws. Because of widespread concern for the welfare of children, laws that protect children in traffic are often easier to enact than similar legislation addressing all ages. This has been the case with child passenger safety legislation in many countries, where such laws preceded seat belt laws or, in some locations, were among the first traffic laws of any kind.

Child safety legislation has often served as an introduction to the concept of traffic rules, and their enactment has increased the willingness of citizens and policy-makers to take further legislative steps that extend protection to the remainder of the population. Examples of child-specific safety legislation include child safety seat laws for infants and toddlers, booster seat and seat belt laws for older children, prohibitions against carrying children in cargo areas of trucks, bicycle helmet laws, bans on carrying children too small to reach footrests on powered two-wheelers, and enhanced penalties for drunk driving if children are in the vehicle.

Target 4.7 of Sustainable Development Goal 4, Quality Education, seeks to “ensure that all learners are provided with the knowledge and skills to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.” Safe routes to school can help ensure that children and youth are exposed to this type of education and that they have the opportunity to use their global citizenship to make a better world, possibly leading change for safer roads in the way that Malala Yousafzai has advocated for women’s education and Greta Thunberg has championed environmental responsibility.

An important part of child and youth education is role modeling by parents and other adults. Young people are influenced by the behaviors of people they respect and admire, so it is important that adults demonstrate the types of road safety attitudes and behaviors that children need in order to be safe road users.

Actions and Responsibilities

An important reason for the shift away from walking and bicycling is the perception of a lack of safety of public spaces. Studies indicate that investment to improve sidewalks and street crossings and provide designated bicycle lanes could increase the number of people using active forms of transportation (Aziz et al. 2018). Programs such as Vision Zero for Youth promote investment in road, pedestrian, and cycling infrastructure, targeting corridors frequently used by children on their route to and from school or recreational facilities. By improving the safety and frequency of walking and bicycling by children and youth, such programs address a range of Sustainable Development Goals, and by following the Safe System approach in designing infrastructure improvements, these programs could serve an important role in introducing communities to Safe System processes.

Infrastructure design needs to accommodate the special needs of children, particularly the younger ones, who cannot be expected to understand and comply with non-intuitive rules or behaviors. Routes traveled by children should use designs such as separated pedestrian walkways to limit risk exposure and include safe crosswalks where children are likely to feel the need to cross the road. Schools have an important responsibility to analyze, propose, and support implementation of safe routes to the schools.

Countries can pay particular attention to the age at which young people are permitted to operate cars, trucks, or powered two-wheelers to ensure that drivers have adequate maturity and judgment. Graduated driver licensing is proven to be effective in facilitating learning and controlling risk exposure for young drivers.

In many countries, children are frequent passengers on powered two-wheelers. Because of the inherent risks of this mode of travel and because smaller children are at particular risk since they often situated on the vehicle in an unstable manner, the goal should be to provide safer modes for child mobility. However, when families have no choice other than a powered two-wheeler for child mobility and needed changes such as transportation planning will take substantial time, countries and local jurisdictions should consider measures that could reduce the risk for children on powered two-wheelers in the shorter term. Such measures could include helmets for children, special lower speed limits for powered two-wheelers carrying small children, or route restrictions that would prevent these vehicles from traveling on busy or higher speed roads where alternatives are available.

This Recommendation Is Linked to Others Including

Zero Speeding, 30 km/h, Modal Shift, Safe Vehicles, Infrastructure, and Procurement.

Recommendation #5: Infrastructure

Summary