Abstract

Background

To produce statements based on the available evidence and an expert consensus (as members of the Lung Ultrasound Working Group of the Italian Society of Analgesia, Anesthesia, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care, SIAARTI) on the use of lung ultrasound for the management of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit.

Methods

A modified Delphi method was applied by a panel of anesthesiologists and intensive care physicians expert in the use of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 intensive critically ill patients to reach a consensus on ten clinical questions concerning the role of lung ultrasound in the following: COVID-19 diagnosis and monitoring (with and without invasive mechanical ventilation), positive end expiratory pressure titration, the use of prone position, the early diagnosis of pneumothorax- or ventilator-associated pneumonia, the process of weaning from invasive mechanical ventilation, and the need for radiologic chest imaging.

Results

A total of 20 statements were produced by the panel. Agreement was reached on 18 out of 20 statements (scoring 7–9; “appropriate”) in the first round of voting, while 2 statements required a second round for agreement to be reached. At the end of the two Delphi rounds, the median score for the 20 statements was 8.5 [IQR 8.9], and the agreement percentage was 100%.

Conclusion

The Lung Ultrasound Working Group of the Italian Society of Analgesia, Anesthesia, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care produced 20 consensus statements on the use of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU. This expert consensus strongly suggests integrating lung ultrasound findings in the clinical management of critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of lung ultrasound (LUS) in the intensive care setting has increased during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. It is being employed as a diagnostic and monitoring tool in patients with COVID-19-related pneumonia—a condition which in some cases evolves into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1]. Lung ultrasound presents many advantages over other imaging techniques: it is readily available at the bedside, thus avoiding the need to transport patients to the radiology department, and it is radiation-free and highly repeatable, making it suitable for lung monitoring purposes [2]. Lung damage in COVID-19 pneumonia is mainly localized to the peripheral regions of the lungs, thus easily accessible to ultrasound [3]. The sensitivity and negative predictive value of LUS for COVID-19 pneumonia are both higher compared with those for chest X-ray [4]. Moreover, many studies show a close correlation between LUS and computed tomography (CT) scan findings [5]. Given the prolonged need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 and long intensive care unit (ICU) stay, repeated lung assessments are usually required. CT remains the reference imaging technique for lung assessment, but it is unsuitable as a monitoring tool due to its use of ionizing radiation. It also necessitates patient contact with healthcare providers outside the ICU, increasing the opportunity for this highly infectious disease to spread. The quantitative evaluation of lung disease by means of the LUS score provides a reliable method for assessing lung aeration in both ARDS and COVID-19, and may further help in monitoring lung recovery and in the daily optimization of ventilation strategies (i.e., positive end-expiration pressure [PEEP] titration, and the use of prone positioning) [6]. Finally, LUS permits the early bedside detection of complications, such as pneumothorax [7] and ventilator-associated pneumonia [8]. As a consequence, LUS has earned a leading position in the management of COVID-19 patients, being a reliable, time-sparing, and easy-to-learn alternative to traditional imaging techniques [9, 10]. However, the recent literature is mainly focused on its applications within the Emergency Department [11]. Although Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound (CIMUS) experts recently established their recommendations for medical inpatients with COVID-19 [12], consensus guidelines dedicated to COVID-19 ICU patients and officially acknowledged by a national intensive care scientific society are lacking. To fill this gap, we aimed to produce an expert consensus on the bedside use of LUS in critically ill COVID-19 patients by a national panel of anesthesiology and intensive care physicians.

Methods

Consensus process design

This project was conducted according to a modified Delphi method to reach consensus on key aspects of the use of LUS in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Discussions were based on the available scientific evidence as well as the panel of experts’ own clinical experience. The experts were selected by the project coordinators (LV and FM) based not only on their clinical and scientific interest in the topic [13] but also the opinion of intensivists who are not experts in LUS but who understand the context of critically ill COVID patients, and the potential role of lung ultrasound was invited. After an initial (online) kick-off meeting between the coordinators, the panelists, the methodologists (AC and DP), and the evidence review team (MI and DO), the project coordinators proposed a list of the most relevant clinical questions to the whole panel, which was then asked to submit a blind boolean vote (“agree/disagree on the relevance”) as well as comments and proposals for their modification. In response, the coordinators made the appropriate changes to the clinical questions, which were finally approved by the whole panel through a second round of voting. The coordinators then assigned the work on each clinical question to a designated group of experts, each of which was led by a designated group head (PP, PN, EB, TB, and SM). The list of clinical questions and the final consensus-based statements is shown in Table 1.

Systematic review of available evidence

A systematic review of MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, and pre-print depositories (medRxiv and bioRxiv) was performed by the evidence review team with the added input of AC. The full search strategy can be found in Additional file 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. S1) of the inclusion/exclusion process can be found in Additional file 2 with the results of the first round of voting (Fig. S2). The full output of the search and the selection of potentially relevant articles (selected by MI and DO, according to the PICO questions and criteria described in Table S1, Additional file 2) can be found in Additional file 3. The last literature search was completed on 16 January 2021. Other sources (i.e., reference lists from relevant articles [i.e., the snowballing method] and online journal issues) were surveyed after the last literature search and up until the end of the first round of voting so that any further relevant articles could be identified and included. The output of the search together with the full texts of all relevant articles was then sent to all panelists. Following the evaluation of the evidence, each panelist produced their statement and rationale in response to each of the given questions.

The Delphi rounds, consensus meeting

Two rounds of voting were held between March and June 2021. The respondents were blinded to each other’s responses. In the first round, expert panelists responded to the online questionnaire and were offered the possibility of adding their opinions using an open text box. The research assistance team (CC, see the “Acknowledgements” section), with the input of the methodologist (AC), assessed and presented the results from round 1 in the form of bar graphs to facilitate the comments and clarifications offered by each participant during an online meeting. During this meeting, the panel openly discussed the statements/rationales on which agreement had not been reached. In some circumstances the discussion led the panelists to reconsider their initial opinions, whereas in others it resulted in the working group modifying the statements. A second round of blind online voting was then held. The results of the consensus process were tabulated and presented both descriptively and graphically. The process was closed on 16 June 2021.

Questionnaire and consensus criteria

The group’s opinion on each statement and rationale was studied in terms of the score and the level of consensus reached by the panelists. The same criteria were applied to each of the statements and rationales. Opinions were expressed using a unique nine-point ordinal Likert-type scale, according to the model developed by UCLA-RAND Corporation (minimum score, 1 = full disagreement; maximum score, 9 = full agreement) [13]. This scale was split into three sections, indicating the level of agreement/disagreement: a score of 1–3 implicated rejection or disagreement (“not appropriate”); 4–6 implicated (“uncertainty”); and 7–9 implicated agreement/support (“appropriate”). Consensus was reached when (i) 75% or more of the respondents, i.e., at least 14 out of 18 experts (excluding the methodologists and the evidence review team), assigned a score within the 3-point ranges 1–3 or 7–9, which rejected or accepted the statements/rationales, respectively; and (ii) the median score also lay within these ranges [14]. The type of consensus achieved was determined by the median score: “agreement” was defined for a median score ≥ 7, and “disagreement” for a median score ≤ 3. A median score within the 4–6 range meant that most of the group had scored the items as “uncertain.”

Results

The panel was composed of a total of 18 experts, 4 methodologists, and 2 senior heads. The panel produced a total of 20 statements. The criteria for a consensus of agreement (i.e., a score in the range 7–9 provided by 75% or more of respondents, and a median score value also within this range) were met for 18 out of 20 statements in the first round of voting. Consensus was not achieved in relation to statements no. 5 and no. 17 (see Fig. S2, Additional file 2). After the second round of voting, consensus of agreement was achieved on all statements. The median score (plus interquartile range) and agreement percentage for all the statements contained in the final consensus report are shown in Fig. 1.

Clinical questions and consensus-based statements

-

A)

Does LUS have a role to play in the diagnosis of COVID-19?

-

Statement 1: LUS should be integrated in the clinical workup to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia.

-

Statement 2: In patients with high clinical suspicion of COVID-19 and LUS findings compatible with ultrasonographic interstitial pneumonia, a negative nasal/oropharyngeal RT-PCR should not be used alone to exclude COVID-19.

-

Statement 3: LUS should not be used alone to rule in and rule out SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in suspected COVID-19.

Lung ultrasound has been shown to improve the diagnostic accuracy in patients who present with acute respiratory symptoms [15]. The reliance on the clinical presentation of patients is a highly ineffective approach for COVID-19 case identification. The sensitivity of using crackles on auscultation for the detection of parenchymal involvement in COVID-19 patients was just 8% when compared to CT as reference [11]. On the contrary, LUS performs better than standard tests for dyspnea in the Emergency Department [16, 17], permitting COVID-19 pneumonia to be diagnosed in patients with normal vital signs [11], and distinguishing between viral and bacterial pneumonias [17]. LUS is more accurate than chest X-ray in diagnosing respiratory conditions [18, 19], including interstitial diseases [20], pneumonia [21], and COVID-19 pneumonia [22]. If the pre-test probability of COVID-19 is low [23], a LUS bilateral A-pattern with sliding makes COVID-19 pneumonia unlikely owing to its high negative predictive value for pneumonia [24, 25]. The strong correlation between CT and LUS scans in COVID-19 patients supports the preferential use of LUS over CT in scenarios where CT is inappropriate (e.g., pregnancy) or difficult to obtain [26]. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing is currently the standard diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is reported to have high specificity but only moderate sensitivity for diagnosing COVID-19 [27, 28]. Coupled with pre-test probability, bilateral B-lines, an irregular pleural line, and sub-pleural consolidations increase the likelihood of COVID-19 diagnosis [29, 30]. A recent meta-analysis of six observational studies and a case series describing a total of 122 symptomatic patients highlights the role of LUS in the diagnosis of COVID-19 [31]. Interstitial lung involvement, as depicted by the B-pattern, was the most common and consistent finding by LUS, and the presence of this finding in addition to other characteristic symptoms will increase the likelihood of diagnosis. The “light beam” artifact is a LUS sign that corresponds to the early appearance of “ground-glass” opacity on a CT scan, and it has been observed in most patients with COVID-19 pneumonia [32, 33]. Some authors have suggested the “light beam” sign to be specific to COVID-19 pneumonia, and its presence may increase the diagnostic likelihood in patients suspected of having COVID-19 [1]. However, LUS should always be integrated into a more comprehensive clinical evaluation, and LUS findings should be interpreted in light of the pre-test probability of COVID-19 pneumonia.

-

B)

Can LUS help in the early assessment of COVID-19 severity in the Emergency Department and/or at ICU admission?

-

Statement 4: Sonographic multifocal and bilateral pleural and lung abnormalities, a high overall LUS score, and/or a high score in the gravity dependent areas can be used for the early assessment of COVID-19 severity in the Emergency Department and at ICU admission since all correlate with worsening patient outcomes—intended as the need for ICU admission, non-invasive ventilation (NIV), intubation, and a higher mortality rate—although ICU admission still remains a clinical decision based on clinical assessment and some related exams.

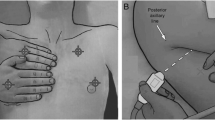

Several observational prospective cohort studies of COVID-19 patients have found a significant correlation between LUS findings and poor outcome, defined as ICU admission, increased likelihood of acute respiratory failure, the need for non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, and a higher hospital mortality rate [34, 35]. In all these studies, LUS scores were based on a 4-level scoring system ranging from 0 to 3, but they differed in the number of areas scanned, which ranged from 6 to 14 lung regions [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Two groups of researchers analyzed the agreement between the different LUS score protocols and patient outcome in COVID-19 patients and concluded that, independently of the number of areas scanned, the accuracy in outcome prediction was higher when the protocol adopted included the evaluation of the gravity dependent areas [44, 45]. One case series and sixteen observational prospective cohort studies have provided consistent results suggesting that, independently of the protocol adopted, a moderate loss of aeration as assessed by LUS is associated with a higher need for NIV, whereas a severe loss of lung aeration is associated with an increased likelihood of ICU admission and mortality [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 51, 54]. In five observational prospective studies [40,41,42, 54, 55], an increased likelihood of NIV failure was associated with a severe loss of lung aeration as assessed by the LUS score, independently of the protocol adopted. In the light of this evidence, and independently of the number of areas scanned and the LUS score protocol adopted, the presence of sonographic multifocal and bilateral pleural and lung abnormalities together with a high overall LUS score and/or high scores in the gravity dependent areas may help in predicting NIV failure, the need for ICU admission, and hospital mortality in the emergency room. The 12-lung-region scoring system usually adopted in critically ill patients is described in Fig. 2.

-

C)

Can LUS be used as a lung monitoring tool in COVID-19 patients undergoing non-invasive respiratory support (HFNC, CPAP, or NIV)?

-

Statement 5: In COVID-19 patients undergoing non-invasive respiratory support (HFNC, CPAP, or NIV), LUS integrated with clinical and physiological parameters may contribute to predict non-invasive respiratory support outcome and early detect complications.

The lung ultrasound score (LUS) can be applied to assess the loss of aeration by dividing the thorax into 12 specific regions, six on the right and six on the left in supine or prone position assign each region a score from 0 (normal lung) to 3 (lung consolidation). Anterior, lateral, and posterior fields are identified by sternum, anterior, and posterior axillary lines. The entire examination can be performed without any change in patient’s position. Score: 0 = normal aeration (A-lines and lung sliding or maximum 2 well-spaced B-lines); score 1 = moderate loss of aeration (> = 3 well-spaced B-lines with lung sliding, coalescent B-lines/subpleural consolidations occupying < 50% of the pleural line); score 2 = severe loss of aeration (> = 3 well-spaced B-lines with lung sliding, coalescent B-lines/subpleural consolidations occupying clearly > 50% of the pleural line); score 3 = complete loss of aeration: lobar/hemilobar consolidation with predominant tissue like pattern

Although robust evidence in COVID-19 patients has yet to be gathered, apart from some interesting case series [56, 57] and a few observational cohort studies involving small sample sizes [58, 59], the role of LUS as a monitoring tool in the field of interstitial lung diseases has already been confirmed since the LUS score is known to correlate with lung aeration [60]. Based on all the evidence available in this setting [37, 39,40,41, 43, 49, 54, 56, 58], the daily assessment of the LUS score in COVID-19 patients undergoing non-invasive respiratory support can be considered an appropriate approach. A worsening overall LUS score, with or without a high LUS score in the gravity dependent areas, may be predictive of a worsening patient outcome and the failure of a 24-h non-invasive respiratory support trial [40,41,42, 54, 56]. On the other hand, a stable or decreasing overall LUS score after a 24-h non-invasive respiratory support trial, together with an improvement in the LUS score in the gravity dependent areas, may be associated with non-invasive respiratory support success. Furthermore, pneumothorax (PNX) and pneumomediastinum are common complications in severe COVID-19 respiratory failure [61, 62], even in patients undergoing non-invasive ventilation, especially if associated with exacerbating inspiratory efforts and high pleural pressure swings. The role of LUS in the early detection and monitoring of PNX is well-known. In fact, the sensitivity and specificity of LUS for the detection of even small occult PNX have been demonstrated to be high [63, 64]. In patients without subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum may be suspected once PNX has been ruled out in the presence of specific ultrasound findings in the subxiphoid view and/or in the anterolateral cervical region [65, 66].

D) Can LUS be used as a lung monitoring tool in COVID-19 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation?

-

Statement 6: LUS should be integrated into the multimodal assessment of disease progression and the response to treatments in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients.

-

Statement 7: LUS should be integrated into the clinical decision-making process and monitoring of procedures, such as fibrobronchoscopy, in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients.

-

Statement 8: LUS should be integrated into the clinical decision-making process and monitoring of treatments, such as antibiotics, in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients.

-

Statement 9: LUS should be integrated into the clinical decision-making process and monitoring of fluid removal in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients.

Specific ultrasound findings provide useful information for the monitoring of mechanically ventilated patients [60, 67]. A complete examination requires only a few minutes and shows high inter-observer agreement even with ultra-portable devices [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Changes in the LUS score over time may help the assessment of disease progression and of the response to treatments in ARDS patients [69,70,71,72]. Monitoring the lung with LUS may improve the management of fluid balance in acute respiratory failure patients [73, 74]. The visualization of a newly appeared tissue-like pattern could point toward/be suggestive of reabsorption atelectasis (if a static or absent air-bronchogram is visualized) [75], ventilator-associated pneumonia (dynamic linear/arborescent air-bronchogram), or lung collapse with patent airways (dynamic punctiform air-bronchogram), thus indicating the need for dis-obstructive fibro-bronchoscopy, distal micro-biological sampling, or titration of positive pressure mechanical ventilation [76]. Pleural line assessment is also of interest in COVID-19 patients. The results of an in vitro study suggest that the persistence of subpleural consolidations and pleural irregularities may be a marker of fibro-proliferative diffuse alveolar damage [77]; in fact, these signs are observed in vivo at admission in patients with long-duration symptoms [78]. When combined with suggestive clinical parameters and compressive vein ultrasound, the presence of large subpleural consolidations are associated with a high probability of pulmonary embolism [79].

-

E)

Can LUS guide the titration of positive end expiratory pressure in severe COVID-19 patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation?

-

Statement 10: LUS should be considered as an additional tool for PEEP titration in COVID-19.

The limitations of LUS as a tool for titrating PEEP levels in COVID-19 patients are the same as those applying to ARDS patients, namely, the limited capability to quantify recruitment and detect hyperinflation. PEEP-induced recruitment in COVID-19 is heterogeneous and limited in most patients [80]. LUS should be considered as an additional tool, complementary to respiratory mechanics and arterial blood gases, for determining and monitoring the effects of PEEP changes [81].

-

F)

Can LUS guide the use of prone positioning in patients with severe COVID-19?

-

Statement 11: LUS should be integrated into the assessment of patients considered potential responders to prone positioning, according to the focal and non-focal pattern of lung aeration loss.

-

Statement 12: LUS can be used to monitor variations in lung aeration during prone positioning.

In conventional ARDS patients, lung ultrasound has been used to monitor the effects of prone positioning on lung reaeration [82, 83]. Haddam et al. showed that ARDS patients with a focal distribution of aeration loss as determined by LUS tended to experience greater reaeration during prone positioning, although it did not correlate with the oxygenation response [84]. In a second study, aeration changes in posterior fields induced by the first 3 h of prone positioning were significantly greater in patients with positive responses and associated with greater levels of oxygenation after 7 days of treatment. Moreover, the lung aeration changes correlated well with the reduction in dead space [85]. Rousset et al. confirm that prone responders present a greater LUS reaeration score at both an early and late stage of prone positioning, corresponding with an increase in end-expiratory lung volume [82]. Similarly, in COVID-19 pneumonia, the improvement in oxygenation following pronation was associated with an improvement in both the global and posterior LUS scores [85]. LUS was proven to be a reliable bedside tool for monitoring lung aeration across the different phases of prone positioning in ARDS patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation. Thus, lung aeration monitoring through LUS imaging during pronation could also constitute a valid solution for COVID-19 pneumonia, in which the early prediction of disease progression may prove to be fundamental for the delivery of appropriate healthcare.

-

G)

Can LUS help early diagnosis of pneumothorax in severe COVID-19 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation?

-

Statement 13: LUS should be used in COVID-19 patients, in line with its clinical appropriateness as ascertained by studies in non-COVID-19 patients.

Analysis of the current literature failed to reveal the presence of studies specifically addressing LUS accuracy in pneumothorax diagnosis in COVID-19 patients. A single observational study by Li et al. [86], involving 42 patients, reported 4 cases of pneumothorax identified by LUS and two cases identified by chest X-ray, but no data on concordance were provided. A multi-center observational study by Zieleskiewicz et al. compared LUS performance against that of CT as the standard reference in the diagnosis of interstitial syndrome, consolidations, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and pleural irregularity [5]. Unfortunately, no pneumothoraxes were present in 100 case samples; thus, the accuracy of LUS in pneumothorax diagnosis could not be estimated. Consistently, a low incidence of pneumothorax in COVID-19 patients was previously reported by Yang et al. in a single-center observational study of 52 patients [87]. Regarding pneumothorax diagnosis and monitoring, LUS applications in COVID-19 patients must currently rely on non-COVID-19 literature. To date, the role of LUS in pneumothorax diagnosis in the critically ill and in trauma patients is well-recognized [63]. Pneumothorax is defined by the presence of air in the pleural cavity, which, in the majority of cases, collects in the upper part (i.e., in the least dependent part), depending on patient position and habitus. Thus, where air collects, the visceral and parietal layers become separated, and a static pleural line replaces normal lung appearance due to the complete reflection of the US beam by the pleural air. This static pleural line has three features: the absence of lung sliding, the lack of B-lines, and the absence of lung pulse [88,89,90]. Pneumothorax can be ruled out in 100% of cases if lung sliding and B lines are present [7]. Only one sign is specific enough to rule pneumothorax in the lung-point [91]. This is the ultrasonographic sign that presents at the pneumothorax border where the visceral and parietal pleural contact each other again. However, lung-point can be challenging to find, or completely absent in very large pneumothorax cases. The accuracy of LUS in pneumothorax diagnosis has been evaluated in many studies, which have been synthesized into four meta-analyses published between 2011 and 2014 [92,93,94,95]. The pooled specificity of LUS is reported to vary between 98 and 99%, comparable to chest X-ray, while sensitivity is reported to be between 79 and 91%, far outperforming chest X-ray, the pooled sensitivity of which varies from 40 to 52%. Moreover, LUS has been shown to be a sensitive tool, with a low air volume threshold, able to detect even radio-occult pneumothoraxes (i.e., undetected by chest X-ray), which may inflate further during mechanical ventilation [96, 97]. LUS has also been shown to be a reliable means for semi-quantifying pneumothorax dimension, thus helping in treatment decision-making [98]. In the context of pneumothorax daily reassessment, some controversy exists regarding diagnostic consistency over time, with only one study reporting LUS to be adequately capable of detecting pneumothorax resolution after chest drain clamping and removal [99]. The presence of subcutaneous emphysema, which may accompany cases of pneumomediastinum, may limit this application, complicating mechanical ventilation in some COVID-19 patients [100].

-

H)

Can LUS help the early diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in severe COVID-19 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation?

-

Statement 14: LUS should be used in COVID-19 patients, in line with its clinical appropriateness as ascertained by studies in non-COVID-19 patients.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most frequent nosocomial infection occurring in the ICU; it is associated with increased mortality, a greater use of antimicrobials, longer mechanical ventilation, and higher healthcare costs. VAP is suspected in patients under mechanical ventilation presenting fever/hypothermia, leukocytosis/leukopenia, purulent tracheal secretions, and impaired oxygenation [39]. No specific studies have been conducted so far to assess the accuracy of LUS in VAP diagnosis in COVID-19 patients. LUS is well suited to investigate interstitial and subpleural involvement in lung disease, and it is increasingly used in the ICU setting. The extent and severity of lung infiltrates can be described numerically with a reproducible and validated LUS score [39]. More recently, quantitative analysis of the LUS score has been proposed to make the interpretation of findings less operator dependent [6]. VAP-related injuries typically extend from the center to the periphery of the lung; when these lesions reach the subpleural regions, they become identifiable by LUS: a normal A-line pattern with lung sliding is replaced by focal areas of interstitial syndrome, represented by well-spaced B-lines, becoming progressively confluent into subpleural areas of consolidation, where air-bronchograms may be visualized [68]. LUS could become a tool for the detection of VAP in the ICU, but this application has only been investigated so far by three specific studies [6, 39, 68]. The current literature on LUS use in routine practice for COVID-19 patients is encouraging as it seems to accurately reflect disease progression [39]. Specific data on LUS accuracy for the diagnosis of VAP in severe COVID-19 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation are still lacking, and well-designed studies are needed to validate this powerful tool [68].

-

I)

Can LUS help the process of weaning severe COVID-19 patients from invasive mechanical ventilation?

-

Statement 15: We are unable to create any statement on the use of LUS in the assessment of patient readiness to sustain a spontaneous breathing trial (SBT). No study has evaluated the potential of LUS for this purpose in COVID-19 patients, and data in non-COVID-19 patients are conflicting.

-

Statement 16: In association with standard clinical and physiological indexes, LUS can improve the prediction of SBT outcome in COVID-19 patients.

-

Statement 17: In association with standard clinical and physiological indexes, LUS can improve the prediction of extubation failure in COVID-19 patients.

The term weaning refers to the whole process leading to the liberation from mechanical ventilation and removal of the endotracheal tube [101]. The process includes a number of steps: (1) assessing spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) readiness; (2) conducting a SBT and assessing its outcome; and (3) predicting extubation failure, which would expose patients to an increased risk of death and prolonged ICU stay [101].

Readiness for SBT is commonly assessed by means of a composite evaluation, including clinical and physiological variables [101]. LUS imaging employed to ascertain patient readiness to undergo an SBT has produced conflicting results in non-COVID-19 patients. In critically ill neurosurgical patients, a high LUS score prior to a 1-h SBT conducted using a T-tube was associated with a higher risk of SBT failure [102]. Conversely, data from a bi-center, prospective, observational investigation, carried out in a heterogeneous population of 250 ready-to-wean patients, showed that B-line predominance prior to sustaining a T-tube SBT lasting 30–120 min was a very weak predictor of SBT outcome, with 47% sensitivity, 64% specificity, a positive predictive value of 25%, and a negative predictive value of 82% [103]. The authors concluded that the presence of B-lines on a simplified 4-zone LUS protocol should not interfere with the decision to initiate weaning procedures [103].

The outcomes of SBTs and extubation depend on a variety of factors, such as cardiovascular dysfunction, inability of the respiratory muscles to sustain an excessive work of breathing, neuromuscular disorders, severe anemia, altered metabolic, nutritional, or neuropsychological conditions, and the inability to clear secretions [101]. While LUS is not helpful for evaluating some of these factors, it may add to the physician’s decision-making when associated with clinical and physiological variables and in some cases with cardiac and diaphragm ultrasound assessment [104,105,106]. In critically ill patients, following the reduction of ventilatory support, the extension of regions affected by aeration loss and pulmonary edema may contribute to weaning failure [105] and can be identified and quantified by LUS [107, 108]. Indeed, variations in LUS patterns reflect changes in pulmonary aeration, which is the final result of different pathways [108,109,110]. Patients who fail an SBT show lung de-recruitment and inhomogeneity according to electric impedance tomography analysis [111]. In patients invasively ventilated for more than 48 h, a 1-h SBT conducted using a T-tube showed a LUS greater than that observed in patients with successful SBT [104]. These results were subsequently confirmed in a second study conducted in the same setting [109]. In patients intubated for acute respiratory failure of different etiologies undergoing an SBT either in T-tube mode or with 8 cmH2O of inspiratory pressure support and 5 cmH2O of positive end-expiratory pressure, the discriminative power of LUS for successful weaning was 0.8 with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.76 and 0.73, respectively [112]. An increase in B-lines to ≥ 6 on four anterior points during a 60-min SBT in T-tube mode was shown to predict weaning-induced pulmonary edema with a sensitivity of 88% (64–98) and a specificity of 88% (62–98) [110]. In elderly patients undergoing an SBT, global and anterolateral LUS predicted failure with a discriminative power of 0.80 and 0.79, respectively [108].

Combining LUS with cardiac and diaphragmatic ultrasound assessment has the potential to improve weaning failure prediction, providing insights into the origin of reduced pulmonary aeration [113, 114]. A modified LUS assessment and diaphragmatic thickening assessment were associated with high predictive accuracy of successful extubation, with an AUC of 0.78 and 0.76, respectively, which increased up to 0.83 when considering both assessments together [112]; however, the relationship between LUS and diaphragm thickening during an SBT seems to vary according to the degree of pulmonary aeration [115], as well as to the considered subpopulation [116]. LUS in association with the brain natriuretic peptide test, diaphragm dysfunction assessment, and left atrial pressure measurement is a better predictor of weaning failure than LUS alone (AUC 0.91 vs 0.76) [117].

In non-COVID-19 patients, LUS was successfully applied to predict extubation outcome. Regardless of the primary cause of the weaning failure, LUS performed in 100 ICU patients during successful SBTs in T-tube mode was able to predict the occurrence of post-extubation distress [112]. A LUS score higher than 17 was associated with an increased risk of extubation failure, whereas a gray zone was identified for scores ranging from 13 to 17. In patients who successfully passed the SBT with a LUS score > 13, non-invasive ventilation was proposed as a rescue strategy to prevent re-intubation [104]. LUS assessment during successful SBTs with support pressure ventilation < 7 cmH2O and no PEEP revealed the occurrence of multiple B-lines as a predictor of post-extubation distress within the first 48 h after extubation [113]. Despite the lack of data in COVID-19 patients, the pathophysiological insights gained from LUS during a SBT to predict extubation failure might be translated to COVID-19 patients. This suggestion arrives from the consideration that observational studies have evaluated the reliability of LUS as a monitoring tool in COVID-19 patients, despite it being a different clinical setting to weaning [42].

Changes in the LUS score during SBTs in COVID-19 patients could add some information concerning the loss of aeration. Cardiac and diaphragm ultrasound assessments might also be able to enhance SBT outcome prediction.

L) Can LUS decrease the need for radiologic chest imaging in severe COVID-19 patients?

Statement 18: In patients with known COVID-19 and severe symptoms, LUS should be performed instead of radiologic chest imaging as the first-line imaging test to monitor disease progression.

-

Statement 19: LUS findings suggestive of pneumonia can render additional imaging techniques unnecessary, especially when the likelihood of an alternative diagnosis is low.

-

Statement 20: In COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms, a negative LUS exam should prompt an additional radiologic chest imaging work-up.

Monitoring critically ill patients by serial chest X-ray is not advisable due to the technique’s low sensitivity and long execution time; moreover, it represents a suboptimal allocation of available resources [19].

Conversely, LUS demonstrates high agreement with chest computer tomography (CT), closely mirrors the longitudinal changes found by CT without exposing the personnel to infection risks, and is quick to perform [9]. If integrated into the daily routine examinations, LUS results appear to accurately reflect disease progression, thus reducing the need for chest X-ray and CT [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118]. Moreover, LUS has been shown capable of monitoring the evolution of severe COVID-19 pneumonia after hospital discharge, supporting its integration into clinical predictive models of residual lung injury, thus providing an alternative imaging modality for the diagnosis and monitoring of critically ill COVID-19 patients [119].

If a patient presents LUS findings suggestive of pneumonia together with a low pre-test probability of an alternative or secondary diagnosis, an additional imaging modality may not be necessary [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120]; however, a chest CT on admission performs better than LUS for COVID-19 diagnosis, at varying disease prevalence [38], and LUS is highly sensitive but not specific for COVID-19 [121]. Thus, the presence of pre-existing conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure, and the prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 must be taken into account when deciding whether to pursue or not additional chest imaging modalities, which should be individualized on a patient-by-patient basis [120].

In patients with severe symptoms, the probability of entirely normal radiologic findings is low. Thus, in patients with severe symptoms, a negative LUS should prompt additional radiologic chest imaging work-up by chest CT owing to its higher accuracy in imaging centrally based abnormalities and diagnosis of pulmonary embolism [122,123,124].

Discussion

The panel produced 20 statements in relation to 10 clinical questions on the bedside use of LUS in COVID-19 critically ill patients, summarizing the latest available literature and the direct experience of the expert panelists. As the use of LUS became ineluctable during this pandemic, anesthesiologists and intensive care physicians have been quick to incorporate this important tool into their armamentarium [1, 2, 4,5,6, 9]. This also reinforces the need to impose training and certification on the use of this tool within our discipline in order to ensure its wider implementation in the near future [125]. Two other groups have proposed consensuses on the use of LUS in the setting of COVID-19 [12, 126]. The Canadian consensus statement on the use of LUS was focused on the assessment of medical inpatients to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia [12]. Our consensus not only confirms the use of LUS for COVID-19 pneumonia diagnosis but also details its use as a monitoring tool in the critically ill. A second multi-organ point-of-care ultrasound consensus for COVID-19 patients included a whole-body ultrasound approach [126]. While it supports the use of LUS as an accurate diagnostic tool, the specific use of LUS in routine ICU work was not detailed. Two other society guidelines have been produced: the first by the German societies of clinical acute, emergency, and intensive care medicine and radiology [127] and the second by the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS) [128]. Both are mainly focused on imaging and monitoring techniques in COVID-19, but do not detail the use of LUS in the critically ill. Finally, the European Society of Radiology recently highlighted the role of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 disease in the ICU, supporting its use “to track the evolution of disease during follow-up and to monitor lung recruitment maneuvers, the response to prone position ventilation and the controlling of extracorporeal membrane therapy” [2].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our expert consensus is the first detailing the use of LUS for diagnosis, management, and monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia in the critically ill patient. We hope that the statements produced will help ICU physicians in their daily clinical practice while facing the ongoing pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the present expert consensus is available, on reasonable request, by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- LUS:

-

Lung ultrasound

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiration pressure

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- HFNC:

-

High flow nasal cannula

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- PNX:

-

Pneumothorax

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- SBT:

-

Spontaneous breathing trial

- BMUS:

-

British Medical Ultrasound Society

References

Volpicelli G, Gargani L, Perlini S, Spinelli S, Barbieri G, Lanotte A, Casasola GG, Nogué-Bou R, Lamorte A, Agricola E, Villén T, Deol PS, Nazerian P, Corradi F, Stefanone V, Fraga DN, Navalesi P, Ferre R, Boero E, Martinelli G, Cristoni L, Perani C, Vetrugno L, McDermott C, Miralles-Aguiar F, Secco G, Zattera C, Salinaro F, Grignaschi A, Boccatonda A, Giostra F, Infante MN, Covella M, Ingallina G, Burkert J, Frumento P, Forfori F, Ghiadoni L, on behalf of the International Multicenter Study Group on LUS in COVID-19, Fraccalini T, Vendrame A, Basile V, Cipriano A, Frassi F, Santini M, Falcone M, Menichetti F, Barcella B, Delorenzo M, Resta F, Vezzoni G, Bonzano M, Briganti DF, Cappa G, Zunino I, Demitry L, Vignaroli D, Scattaglia L, di Pietro S, Bazzini M, Capozza V, González MM, Gibal RV, Ibarz RP, Alfaro LM, Alfaro CM, Alins MG, Brown A, Dunlop H, Ralli ML, Persona P, Russel FM, Pang PS, Rovida S, Deana C, Franchini D (2020) on behalf of the International Multicenter Study Group on LUS in COVID-19. Lung ultrasound for the early diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia: an international multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 47(4):444–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06373-7

European Society of Radiology (ESR) (2021) The role of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 disease. Insights Imaging 12(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-021-01013-6

Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, Fan Y, Zheng C (2020) Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20(4):425–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4

Gibbons RC, Magee M, Goett H, Murret J, Genninger J, Mendez K, Tripod M et al (2021) Lung ultrasound vs. chest X-ray study for the radiographic diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia in a high-prevalence population. J Emerg Med 60(5):615–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.01.041

Zieleskiewicz L, Markarian T, Lopez A, Taguet C, Mohammedi N, Boucekine M, Baumstarck K, Besch G, Mathon G, Duclos G, Bouvet L, Michelet P, Allaouchiche B, Chaumoître K, di Bisceglie M, Leone M, on behalf of the AZUREA Network (2020) AZUREA Network. Comparative study of lung ultrasound and chest computed tomography scan in the assessment of severity of confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 46(9):1707–1713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06186-0

Mongodi S, De Luca D, Colombo A, Stella A, Santangelo E, Corradi F et al (2021) Quantitative lung ultrasound: technical aspects and clinical applications. Anesthesiology 134(6):949–965. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003757

Volpicelli G (2011) Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med 37:224–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-010-2079-y

Mongodi S, Via G, Girard M, Rouquette I, Misset B, Braschi A, Mojoli F, Bouhemad B (2016) Lung ultrasound for early diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 149(4):969–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.012

Vetrugno L, Bove T, Orso D, Barbariol F, Bassi F, Boero E, Ferrari G, Kong R (2020) Our Italian experience using lung ultrasound for identification, grading and serial follow-up of severity of lung involvement for management of patients with COVID-19. Echocardiography. 37(4):625–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.14664

Meroi F, Orso D, Vetrugno L, Bove T (2021) Lung ultrasound score in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a waste of time or a time-saving tool? Acad Radiol 28(9):1323–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2021.06.008

Hankins A, Bang H, Walsh P. (2020) Point of care lung ultrasound is useful when screening for COVID-19 in emergency department patients. medRxiv [Preprint]. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.09.20123836.

Ma IWY, Hussain A, Wagner M, Walker B, Chee A, Arishenkoff S, Buchanan B, Liu RB, Mints G, Wong T, Noble V, Tonelli AC, Dumoulin E, Miller DJ, Hergott CA, Liteplo AS (2021) Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound (CIMUS) expert consensus statement on the use of lung ultrasound for the assessment of medical inpatients with known or suspected coronavirus disease. J Ultrasound Med 40(9):1879–1892. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15571

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, et al. (2001) The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual [Internet]. Available from: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM et al (2014) Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 67:401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

Laursen CB, Sloth E, Lassen AT, Rd C, Lambrechtsen J, Madsen PH et al (2014) Point-of-care ultrasonography in patients admitted with respiratory symptoms: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2(8):638–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70135-3

Pivetta E, Goffi A, Lupia E, Tizzani M, porrino G, Ferreri E, et al. (2015) SIMEU Group for lung ultrasound in the emergency department in piedmont. Lung ultrasound-implemented diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in the ED: a SIMEU multicenter study. Chest. 148(1):202–210. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2608

Tan G, Lian X, Zhu Z, Wang Z, Huang F, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, He S, Wang X, Shen H, Lyu G (2020) Use of lung ultrasound to differentiate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia from community-acquired pneumonia. Ultrasound Med Biol 46(10):2651–2658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.05.006

Vezzani A, Manca T, Brusasco C, Santori G, Valentino M, Nicolini F, Molardi A, Gherli T, Corradi F (2014) Diagnostic value of chest ultrasound after cardiac surgery: a comparison with chest X-ray and auscultation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 28(6):1527–1532. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2014.04.012

Tierney DM, Huelster JS, Overgaard JD, Plunkett MB, Boland LL, St Hill CA et al (2020) Comparative performance of pulmonary ultrasound, chest radiograph, and CT among patients with acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 48(2):151–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004124

Corradi F, Ball L, Brusasco C, Riccio AM, Baroffio M, Bovio G, Pelosi P, Brusasco V (2013) Assessment of extravascular lung water by quantitative ultrasound and CT in isolated bovine lung. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 187(3):244–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2013.04.002

Ye X, Xiao H, Chen B, Zhang S (2015) Accuracy of lung ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10(6):e0130066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130066

Pare JR, Camelo I, Mayo KC, Leo MM, Dugas JN, Nelson KP, Baker W, Shareef F, Mitchell P, Schechter-Perkins E (2020) Point-of-care lung ultrasound is more sensitive than chest radiograph for evaluation of COVID-19. West J Emerg Med 21(4):771–778. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.5.47743

Llamas-Álvarez AM, Tenza-Lozano EM, Latour-Pérez J (2017) Accuracy of lung ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 151(2):374–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.039

Volpicelli G, Lamorte A, Villén T (2020) What’s new in lung ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive Care Med 46(7):1445–1448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06048-9

Kirkpatrick AW, McKee JL (2021) Re: “Proposal for international standardization of the use of lung ultrasound for patients with COVID-19: a simple, quantitative, reproducible method”- could telementoring of lung ultrasound reduce health care provider risks, especially for paucisymptomatic home-isolating patients? J Ultrasound Med 40(1):211–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15390

Poggiali E, Dacrema A, Bastoni D, Tinelli V, Demichele E, Mateo Ramos P, Marcianò T, Silva M, Vercelli A, Magnacavallo A (2020) Can lung US help critical care clinicians in the early diagnosis of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia? Radiology 295(3):E6. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200847

Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, Ji W (2020) Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology 296(2):E115–E117. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200432

Schultz MJ, Sivakorn C, Dondorp AM (2020) Challenges and opportunities for lung ultrasound in novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Am J Trop Med Hyg 102(6):1162–1163. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0323

Peyrony O, Marbeuf-Gueye C, Truong V, Giroud M, Rivière C, Khenissi K, Legay L, Simonetta M, Elezi A, Principe A, Taboulet P, Ogereau C, Tourdjman M, Ellouze S, Fontaine JP (2020) Accuracy of emergency department clinical findings for diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Emerg Med 76(4):405–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.022

Tung-Chen Y, Algora-Martín A, Llamas-Fuentes R, Rodrìguez-Fuertes P, Martìnez Virto AM, Sanz-Rodrìguez E et al (2021) Point-of-care ultrasonography in the initial characterization of patients with COVID-19. Med Clin (Barc) 156(10):477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.12.007

Mohamed MFH, Al-Shokri S, Yousaf Z, Danjuma M, Parambil J, Mohamed S et al (2020) Frequency of abnormalities detected by point-of-care lung ultrasound in symptomatic COVID-19 patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 103(2):815–821. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0371

Vetrugno L, Baciarello M, Bignami E, Bonetti A, Saturno F, Orso D, Girometti R, Cereser L, Bove T (2020) The “pandemic” increase in lung ultrasound use in response to COVID-19: can we complement computed tomography findings? A narrative review. Ultrasound J 12(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00185-4

Kalafat E, Yaprak E, Cinar G, Varli B, Ozisik S, Uzun C, Azap A, Koc A (2020) Lung ultrasound and computed tomographic findings in pregnant woman with COVID-19. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 55(6):835–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.22034

Bonadia N, Carnicelli A, Piano A, Buonsenso D, Gilardi E, Kadhim C, Torelli E, Petrucci M, di Maurizio L, Biasucci DG, Fuorlo M, Forte E, Zaccaria R, Franceschi F (2020) Lung ultrasound findings are associated with mortality and need for intensive care admission in COVID-19 patients evaluated in the emergency department. Ultrasound Med Biol 46(11):2927–2937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.07.005

Bosso G, Allegorico E, Pagano A, Porta G, Serra C, Minerva V, Mercurio V, Russo T, Altruda C, Arbo P, de Sio C, dello Vicario F, Numis FG (2021) Lung ultrasound as diagnostic tool for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Intern Emerg Med 16(2):471–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02512-y

Brahier T, Meuwly JY, Pantet O, Brochu Vez MJ, Gerhard Donnet H, Hartley MA, Hugli O, Boillat-Blanco N (2020) Lung ultrasonography for risk stratification in patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1408

Castelao J, Graziani D, Soriano JB, Izquierdo JL (2021) Findings and prognostic value of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 pneumonia. J Ultrasound Med 40(7):1315–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15508

Colombi D, Petrini M, Maffi G, Villani GD, Bodini FC, Morelli N, Milanese G, Silva M, Sverzellati N, Michieletti E (2020) Comparison of admission chest computed tomography and lung ultrasound performance for diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia in populations with different disease prevalence. Eur J Radiol 133:109344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109344

Dargent A, Chatelain E, Kreitmann L, Quenot JP, Cour M, Argaud L (2020) Lung ultrasound score to monitor COVID-19 pneumonia progression in patients with ARDS.; COVID-LUS study group. PLoS One 15(7):e0236312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236312

de Alencar JCG, Marchini JFM, Marino LO, da Costa Ribeiro SC, Bueno GG, da Cunha VP et al (2021) Lung ultrasound score predicts outcomes in COVID-19 patients admitted to the emergency department. Ann Intensive Care 11(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00799-w

Deng Q, Zhang Y, Wang H, Chen L, Yang Z, Peng Z, Liu Y, Feng C, Huang X, Jiang N, Wang Y, Guo J, Sun B, Zhou Q (2020) Semiquantitative lung ultrasound scores in the evaluation and follow-up of critically ill patients with COVID-19: a single-center study. Acad Radiol 27(10):1363–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2020.07.002

Ji L, Cao C, Gao Y, Zhang W, Xie Y, Duan Y, Kong S, You M, Ma R, Jiang L, Liu J, Sun Z, Zhang Z, Wang J, Yang Y, Lv Q, Zhang L, Li Y, Zhang J, Xie M (2020) Prognostic value of bedside lung ultrasound score in patients with COVID-19. Crit Care 24(1):700. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03416-1

Lichter Y, Topilsky Y, Taieb P, Banai A, Hochstadt A, Merdler I, Gal Oz A, Vine J, Goren O, Cohen B, Sapir O, Granot Y, Mann T, Friedman S, Angel Y, Adi N, Laufer-Perl M, Ingbir M, Arbel Y, Matot I, Szekely Y (2020) Lung ultrasound predicts clinical course and outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med 46(10):1873–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06212-1

Mento F, Perrone T, Narvena Macioce V, Tursi F, Buonsenso D, Torri E et al (2020) On the impact of different lung ultrasound imaging protocols in the evaluation of patients affected by coronavirus disease 2019: how many acquisitions are needed? J Ultrasound Med 40(10):2235–2238. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15580

Perrone T, Soldati G, Padovini L, Fiengo A, Lettieri G, Sabatini U, Gori G, Lepore F, Garolfi M, Palumbo I, Inchingolo R, Smargiassi A, Demi L, Mossolani EE, Tursi F, Klersy C, di Sabatino A (2021) A new lung ultrasound protocol able to predict worsening in patients affected by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pneumonia. J Ultrasound Med 40(8):1627–1635. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15548

Rojatti M, Regli IB, Zanforlin A, Ferretti E, Falk M, Strapazzon G, Gamper M, Zanon P, Bock M, Rauch S (2020) Lung ultrasound and respiratory pathophysiology in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients an observational trial. SN Compr Clin Med:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00536-1

Sahu AK, Mathew R, Bhoi S, Sinha TP, Nayer J, Aggarwal P et al (2021) Lung sonographic findings in COVID-19 patients. Am J Emerg Med 45:324–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.080

Zhao L, Yu K, Zhao Q, Tian R, Xie H, Xie L, Deng P, Xie G, Bao A, du J (2020) Lung ultrasound score in evaluating the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Ultrasound Med Biol 46(11):2938–2944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.07.024

Zhu ST, Tao FY, Xu JH, Liao SS, shen CL, Liang ZH, et al. (2021) Utility of point-of-care lung ultrasound for clinical classification of COVID-19. Ultrasound Med Biol 47(2):214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.09.010

Zhu F, Zhao X, Wang T, Guo F, Xue H, Chang P et al (2021) Ultrasonic characteristics and severity assessment of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, observational study. Eng (Beijing) 7:367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.09.007

Wangüemert Pérez AL, Figueira Gonçalves JM, Hernández Pérez JM, Ramallo Fariña Y, Del Castillo Rodriguez JC (2021) Prognostic value of lung ultrasound and its link with inflammatory biomarkers in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Respir Med Res 79:100809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmer.2020.100809

Veronese N, Sbrogiò LG, Valle R, Marin L, Boscolo Fiore E, Tiozzo A (2020) Prognostic value of lung ultrasonography in older nursing home residents affected by COVID-19. J Am Med Dir Assoc 21(10):1384–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.07.034

Recinella G, Marasco G, Tufoni M, Brizi M, Evangelisti E, Maestri L, Fusconi M, Calogero P, Magalotti D, Zoli M (2021) Clinical role of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronavirus disease pneumonia in elderly patients: a pivotal study. Gerontology 67(1):78–86. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512209

Biasucci DG, Buonsenso D, Piano A, Bonadia N, Vargas J, Settanni D, et al. (2021) Lung ultrasound predicts non-invasive ventilation outcome in COVID-19 acute respiratory failure: a pilot study. Minerva Anestesiol. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.21.15188-0.

Smargiassi A, Soldati G, Torri E, Mento F, Milardi D, Del Giacomo P et al (2021) Lung ultrasound for COVID-19 patchy pneumonia: extended or limited evaluations? J Ultrasound Med 40(3):521–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15428

Seiler C, Klingberg C, Hårdstedt M (2021) Lung Ultrasound for identification of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J Ultrasound Med 40(11):2339–2351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15617

Magnani E, Mattei L, Paolucci E, Magalotti G, Giacalone N, Praticò C, Praticò B, Zani MC (2020) Lung ultrasound in severe COVID-19 pneumonia in the sub-intensive care unit: beyond the diagnostic purpose. Respir Med Case Rep 31:101307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101307

Mongodi S, Santangelo E, Salve G, Pregnolato S, Bonaiti S, Stella A et al (2019) Lung ultrasound score to monitor non-invasive respiratory support in hypoxemic patients. Eur Respir J 54:PA2322. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA2322

Bouhemad B, Brisson H, Le-Guen M, Arbelot C, Lu Q, Rouby JJ (2011) Bedside ultrasound assessment of positive end-expiratory pressure-induced lung recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183(3):341–347. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003340

Mojoli F, Bouhemad B, Mongodi S, Lichtenstein D (2019) Lung ultrasound for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199(6):701–714. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201802-0236CI

López Vega JM, Parra Gordo ML, Diez Tascón A, Ossaba Vélez S. (2020) Pneumomediastinum and spontaneous pneumothorax as an extrapulmonary complication of COVID-19 disease. Emerg Radiol. 27:727-730 doi.org/10.1007/ s10140-020-01806-0.

Nalewajska M, Feret W, Wojczyński Ł, Witkiewicz W, Wisniewska M, Kotfis K (2021) Spontaneous pneumothorax in COVID-19 patients treated with high-flow nasal cannula outside the ICU: a case series. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):2191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042191

Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, Lichtenstein DA, Mathis G, Kirkpatrick AW, International liaison committee on lung ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for international consensus conference on lung ultrasound (ICC-LUS) et al (2012) International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 38(4):577–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4

Soldati G, Testa A, Pignataro G, Portale G, Biasucci DG, Leone A, Silveri NG (2006) The ultrasonographic deep sulcus sign in traumatic pneumothorax. Ultrasound Med Biol 32(8):1157–1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.006

NG L, Saul T, Lewiss RE. (2013) Sonographic evidence of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Am J Emerg Med 31:462.e3–462.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2012.08.019

Testa A, Candelli M, Pignataro G, Costantini AM, Pirronti T, Silveri NG (2008) Sonographic detection of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. J Ultrasound Med 27(10):1508–1509. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2008.27.10.1507

Bouhemad B, Mongodi S, Via G, Rouquette I (2015) Ultrasound for “lung monitoring” of ventilated patients. Anesthesiology 122(2):437–447. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000558

Pradhan S, Shrestha PS, Shrestha GS, Marhatta MN (2020) Clinical impact of lung ultrasound monitoring for diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia: a diagnostic randomized controlled trial. J Crit Care 58:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.012

Chiumello D, Mongodi S, Algieri I, Vergieri GL, Orlando A, Via G et al (2018) Assessment of lung aeration and recruitment by CT scan and ultrasound in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care Med 46(11):1761–1768. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003340

Bouhemad B, Liu ZH, Arbelot C, Zhang M, Ferrari F, Le-Guen M et al (2010) Ultrasound assessment of antibiotic-induced pulmonary reaeration in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med 38(1):84–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b08cdb

Mongodi S, Pozzi M, Orlando A, Bouhemad B, Stella A, Tavazzi G, Via G, Iotti GA, Mojoli F (2018) Lung ultrasound for daily monitoring of ARDS patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: preliminary experience. Intensive Care Med 44(1):123–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4941-7

Mongodi S, Colombo A, Orlando A, Cavagna L, Bouhemad B, Lotti GA et al (2020) Combined ultrasound-CT approach to monitor acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease. Ultrasound J 12(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00174-7

Caltabeloti F, Monsel A, Arbelot C, Brisson H, Lu Q, Gu WJ et al (2014) Early fluid loading in acute respiratory distress syndrome with septic shock deteriorates lung aeration without impairing arterial oxygenation: a lung ultrasound observational study. Crit Care 18(3):R91. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13859

Torino C, Gargani L, Sicari R, Letachowicz K, Ekart R, Fliser D, Covic A, Siamopoulos K, Stavroulopoulos A, Massy ZA, Fiaccadori E, Caiazza A, Bachelet T, Slotki I, Martinez-Castelao A, Coudert-Krier MJ, Rossignol P, Gueler F, Hannedouche T, Panichi V, Wiecek A, Pontoriero G, Sarafidis P, Klinger M, Hojs R, Seiler-Mussler S, Lizzi F, Siriopol D, Balafa O, Shavit L, Tripepi R, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Picano E, London GM, Zoccali C (2016) The agreement between auscultation and lung ultrasound in hemodialysis patients: the LUST Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11(11):2005–2011. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03890416

Lichtenstein D, Mezière G, Seitz J (2009) The dynamic air bronchogram. A lung ultrasound sign of alveolar consolidation ruling out atelectasis. Chest. 135(6):1421–1425. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2281

Mojoli F, Bouhemad B, Volpicelli G, Mongodi S (2020) Lung ultrasound modifications induced by fibreoptic bronchoscopy may improve early bedside ventilator-associated pneumonia diagnosis: a case series. Eur J Anaesthesiol 37(10):946–949. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001254

de Almeida Monteiro RA, Duarte-Neto AN, Ferraz da Silva LF, de Oliveira EP, do ECT N, Mauad T et al (2021) Ultrasound assessment of pulmonary fibroproliferative changes in severe COVID-19: a quantitative correlation study with histopathological findings. Intensive Care Med 47(2):199–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06328-4

Haaksma ME, Heldeweg MLA, Lopez Matta JE, Smit JM, van Trigt JD, Nooitgedacht JS et al (2020) Lung ultrasound findings in patients with novel SARS-CoV-2. ERJ Open Res 6(4):00238–02020. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00238-2020

Zotzmann V, Lang CN, Wengenmayer T, Bemtgen X, Schmid B, Muller-Peltzer K et al (2021) Combining lung ultrasound and wells score for diagnosing pulmonary embolism in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis 52(1):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02323-0

Mauri T, Spinelli E, Scotti E, Colussi G, basile MC, Crotti S, et al. (2020) Potential for lung recruitment and ventilation-perfusion mismatch in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome from coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med 48(8):1129–1134. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004386

Ball L, Robba C, Maiello L, Herrmann J, Gerard SE, Xin Y et al (2021) GECOVID (GEnoa COVID-19) group. Computed tomography assessment of PEEP-induced alveolar recruitment in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit Care 25(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03477-w

Rousset D, Sarton B, Riu B, Bataille B, Silva S, of the PLUS study group (2021) Bedside ultrasound monitoring of prone position induced lung inflation. Intensive Care Med 47(5):626–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06347-9

Wang XT, Ding X, Zhang HM, Chen H, Su LX, Liu DW et al (2016) Chinese Critical Ultrasound Study Group (CCUSG). Lung ultrasound can be used to predict the potential of prone positioning and assess prognosis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 20:385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1558-0

Haddam M, Zieleskiewicz L, Perbet S, Baldovini A, Guervilly C, Arbelot C, CAR’Echo Collaborative Network, AzuRea Collaborative Network et al (2016) Lung ultrasonography for assessment of oxygenation response to prone position ventilation in ARDS. Intensive Care Med 42(10):1546–1556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4411-7

Avdeev SN, Nekludova GV, Trushenko NV, Tsareva NA, Yaroshetskiy AI, Kosanovic D et al (2021) Lung ultrasound can predict response to the prone position in awake non-intubated patients with COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 25(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03472-1

Li R, Liu H, Qi H, Yuan Y, Zou X, Huang H, Wan J, Lv Z, Ouyang Y, Pan S, Zhao X, Shu H, Shang Y (2021) Lung ultrasound assessment of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by coronavirus disease 2019: an observational study. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 28(1):8–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024907920969326

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H et al (2020) Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 8(5):475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y (1995) A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill. Lung sliding. Chest 108(5):1345–1348. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.5.1345

Lichtenstein D, Mezière G, Biderman P, Gepner A (1999) The comet-tail artifact: an ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med 25(4):383–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340050862

Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Prin S, Mezière G (2003) The “lung pulse”: an early ultrasound sign of complete atelectasis. Intensive Care Med 29(12):2187–2192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-1930-9

Lichtenstein D, Mezière G, Biderman P, Gepner A (2000) The “lung point”: an ultrasound sign specific to pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med 26(10):1434–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340000627

Ding W, Shen Y, Yang J, He X, Zhang M (2011) Diagnosis of pneumothorax by radiography and ultrasonography: a meta-analysis. Chest. 140(4):859–866. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2946

Alrajhi K, Woo MY, Vaillancourt C (2012) Test characteristics of ultrasonography for the detection of pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 141(3):703–708. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-0131

Alrajab S, Youssef AM, Akkus NI, Caldito G (2013) Pleural ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax: review of the literature and meta-analysis. Crit Care 17(5):R208. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13016

Ebrahimi A, Yousefifard M, Mohammad Kazemi H, Rasouli HR, Asady H, Moghadas Jafari A, Hosseini M (2014) Diagnostic accuracy of chest ultrasonography versus chest radiography for identification of pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tanaffos 13(4):29–40

Oveland NP, Søreide E, Lossius HM, Johannessen F, Wemmelund KB, Aagaard R, Sloth E (2013) The intrapleural volume threshold for ultrasound detection of pneumothoraces: an experimental study on porcine models. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 21(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-21-11

Oveland NP, Lossius HM, Wemmelund K, Stokkeland PJ, Knudsen L, Sloth E (2013) Using thoracic ultrasonography to accurately assess pneumothorax progression during positive pressure ventilation: a comparison with CT scanning. Chest. 143(2):415–422. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1445

Volpicelli G, Boero E, Sverzellati N, Cardinale L, Busso M, Boccuzzi F et al (2014) Semi-quantification of pneumothorax volume by lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 40(10):1460–1467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3402-9

Galbois A, Ait-Oufella H, Baudel JL, Kofman T, Bottero J, Viennot S, Rabate C, Jabbouri S, Bouzeman A, Guidet B, Offenstadt G, Maury E (2010) Pleural ultrasound compared with chest radiographic detection of pneumothorax resolution after drainage. Chest. 138(3):648–655. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-2224

Belletti A, Palumbo D, Zangrillo A, Fominskly EV, Franchini S, Dell’Acqua A, et al. (2021) COVID-BioB Study Group. Predictors of pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2021.02.008.

Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, Herridge M, Marsh B, Melot C, Pearl R, Silverman H, Stanchina M, Vieillard-Baron A, Welte T (2007) Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J 29(5):1033–1056. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00010206

Sachin S, Chakrabarti D, Gopalakrishna KN, Bharadwaj S (2021) Ultrasonographic evaluation of lung and heart in predicting successful weaning in mechanically ventilated neurosurgical patients. J Clin Monit Comput 35(1):189–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-020-00460-8

Antonio ACP, Knorst MM, Teixeira C (2018) Lung ultrasound prior to spontaneous breathing trial is not helpful in the decision to wean. Respir Care 63(7):873–878. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.05817

Soummer A, Perbet S, Brisson H, Arbelot C, Constantin JM, Lu Q, Rouby JJ, Lung Ultrasound Study Group (2012) Lung ultrasound study group. Ultrasound assessment of lung aeration loss during a successful weaning trial predicts postextubation distress*. Crit Care Med 40(7):2064–2072. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e68ae

Tuinman PR, Jonkman AH, Dres M, Shi ZH, Goligher EC, Goffi A, de Korte C, Demoule A, Heunks L (2020) Respiratory muscle ultrasonography: methodology, basic and advanced principles and clinical applications in ICU and ED patients-a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 46(4):594–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05892-8

Papanikolaou J, Makris D, Saranteas T, Karakitsos D, Zintzaras E, Karabinis A, Kostopanagiotou G, Zakynthinos E (2011) New insights into weaning from mechanical ventilation: left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is a key player. Intensive Care Med 37(12):1976–1985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2368-0

Bruni A, Garofalo E, Pasin L, Serraino GF, Cammarota G, Longhini F, Landoni G, Lembo R, Mastroroberto P, Navalesi P (2020) MaGIC (Magna Graecia Intensive care and Cardiac surgery) Group. Diaphragmatic dysfunction after elective cardiac surgery: a prospective observational study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 34(12):3336–3344. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2020.06.038

Bouhemad B, Mojoli F, Nowobilski N, Hussain A, Rouquette I, Guinot PG, Mongodi S (2020) Use of combined cardiac and lung ultrasound to predict weaning failure in elderly, high-risk cardiac patients: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med 46(3):475–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05902-9

Jabaudon M, Perbet S, Pereira B, Soummer A, Roszyk L, Guérin R, Futier E, Lu Q, Bazin JE, Sapin V, Rouby JJ, Constantin JM (2013) Plasma levels of sRAGE, loss of aeration and weaning failure in ICU patients: a prospective observational multicenter study. PLoS One 8(5):e64083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064083

Ferré A, Guillot M, Lichtenstein D, Mezière G, Richard C, Teboul JL, Monnet X (2019) Lung ultrasound allows the diagnosis of weaning-induced pulmonary oedema. Intensive Care Med 45(5):601–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05573-6

Longhini F, Maugeri J, Andreoni C, Ronco C, Bruni A, Garofalo E, Pelaia C, Cavicchi C, Pintaudi S, Navalesi P (2019) Electrical impedance tomography during spontaneous breathing trials and after extubation in critically ill patients at high risk for extubation failure: a multicenter observational study. Ann Intensive Care 9(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0565-0

Tenza-Lozano E, Llamas-Alvarez A, Jaimez-Navarro E, Fernàndez-Sànchez J (2018) Lung and diaphragm ultrasound as predictors of success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Ultrasound J 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-018-0094-3

Silva S, Ait Aissa D, Cocquet P, Hoarau L, Ruiz J, Ferre F, Rousset D, Mora M, Mari A, Fourcade O, Riu B, Jaber S, Bataille B (2017) Combined thoracic ultrasound assessment during a successful weaning trial predicts postextubation distress. Anesthesiology 127(4):666–674. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001773

Vetrugno L, Brussa A, Guadagnin GM, Orso D, De Lorenzo F, Cammarota G et al (2020) Mechanical ventilation weaning issues can be counted on the fingers of just one hand: part 2. Ultrasound J 12(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00160-z

Xia J, Qian CY, Yang L, Li MJ, Liu XX, Yang T, Lu Q (2019) Influence of lung aeration on diaphragmatic contractility during a spontaneous breathing trial: an ultrasound study. J Intensive Care 7(1):54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-019-0409-x

Cammarota G, Rossi E, Vitali L, Simonte R, Sannipoli T, Anniciello F et al (2021) Effect of awake prone position on diaphragmatic thickening fraction in patients assisted by noninvasive ventilation for hypoxemic acute respiratory failure related to novel coronavirus disease. Crit Care 25(1):305 doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03735-x

Xu X, Wu R, Zhang YJ, Li HW, He XH, Wang SM (2020) Value of combination of heart, lung, and diaphragm ultrasound in predicting weaning outcome of mechanical ventilation. Med Sci Monit 26:e924885. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.924885

Mongodi S, Orlando A, Arisi E, Tavazzi G, Santangelo E, Caneva L, Pozzi M, Pariani E, Bettini G, Maggio G, Perlini S, Preda L, Iotti GA, Mojoli F (2020) Lung ultrasound in patients with acute respiratory failure reduces conventional imaging and health care provider exposure to COVID-19. Ultrasound Med Biol 46(8):2090–2093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.04.033

Alharthy A, Abuhamdah M, Balhamar A, Faqihi F, Nasim N, Ahmad S, Noor A, Tamim H, Alqahtani SA, Abdulaziz al Saud AAASB, Kutsogiannis DJ, Brindley PG, Memish ZA, Karakitsos D, Blaivas M (2021) Residual lung injury in patients recovering from COVID-19 critical illness: a prospective longitudinal point-of-Care lung ultrasound study. J Ultrasound Med 40(9):1823–1838. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15563

Volpicelli G, Gargani L (2020) Sonographic signs and patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia. Ultrasound J 12(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00171-w

Vetrugno L, Bove T, Orso D, Bassi F, Boero E, Ferrari G (2020) Lung ultrasound and the COVID-19 “Pattern”: not all that glitters today is gold tomorrow. J Ultrasound Med 39(11):2281–2282. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15327

Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, Foppen M, Vlaar AP, Müller MCA et al (2020) Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 18(8):1995–2002. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14888

Artifoni M, Danic G, Gautier G, Gicquel P, Boutoille D, Raffi F, Néel A, Lecomte R (2020) Systematic assessment of venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients receiving thromboprophylaxis: incidence and role of D-dimer as predictive factors. J Thromb Thrombolysis 50(1):211–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02146-z

Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J (2020) Chest CT for typical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 296(2):E41–E45. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200343