Abstract

Background

Due to striking disparities in the implementation of healthcare innovations, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners can meaningfully use implementation determinant frameworks to understand why disparities exist in access, receipt, use, quality, or outcomes of healthcare. Our prior work documented and piloted the first published adaptation of an existing implementation determinant framework with health equity domains to create the Health Equity Implementation Framework. We recommended integrating these three health equity domains to existing implementation determinant frameworks: (1) culturally relevant factors of recipients, (2) clinical encounter or patient-provider interaction, and (3) societal context (including but not limited to social determinants of health). This framework was developed for healthcare and clinical practice settings. Some implementation teams have begun using the Health Equity Implementation Framework in their evaluations and asked for more guidance.

Methods

We completed a consensus process with our authorship team to clarify steps to incorporate a health equity lens into an implementation determinant framework.

Results

We describe steps to integrate health equity domains into implementation determinant frameworks for implementation research and practice. For each step, we compiled examples or practical tools to assist implementation researchers and practitioners in applying those steps. For each domain, we compiled definitions with supporting literature, showcased an illustrative example, and suggested sample quantitative and qualitative measures.

Conclusion

Incorporating health equity domains within implementation determinant frameworks may optimize the scientific yield and equity of implementation efforts by assessing and ideally addressing implementation and equity barriers simultaneously. These practical guidance and tools provided can assist implementation researchers and practitioners to concretely capture and understand barriers and facilitators to implementation disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health equity occurs when all people have socially just opportunities for optimal well-being. Disparities in healthcare implementation exist when a healthcare innovation, such as a program or treatment, is delivered with significantly worse access, receipt, use, quality, or outcomes for certain populations compared to others [1]. Structural factors and systems greatly contribute to different as well as unjust or unfair treatment of certain populations. Populations that experience worse health or healthcare might be defined by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, functional limitation, or other characteristics [2]; we refer to these groups as marginalized populations based on social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage that accompanies health inequities [3]. One example of an implementation disparity in United States (U.S.) pediatric healthcare is screening and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Although there are valid and reliable autism screenings and clear criteria for diagnosis, racial and ethnic minority children who meet the criteria are less likely to be diagnosed than non-Hispanic white children [4]. Thus, effective screenings and diagnoses are implemented inequitably for racial and ethnic minority children, resulting in delayed treatment for children of color. This implementation disparity is exacerbated when children are finally diagnosed properly with autism, as children of color are less likely to receive quality treatment [5]. Unfortunately, several implementation disparities may be undetected. As Braveman wrote, “Health disparities are the metric we use to measure progress toward achieving health equity” [3].

Overall, implementation science has yet to actively and systematically assess, address, and evaluate unique factors contributing to healthcare inequities, including institutional and structural problems, such as racism, that are economic, regulatory, social, historical, and political determinants of implementation for marginalized groups [6]. There are many reasons why implementation researchers have yet to showcase solutions to healthcare inequities including underrepresentation of marginalized and resource-poor communities in implementation studies [6, 7], lack of true engagement with marginalized communities in developing implementation science and practice [8], lack of consistent methods and data elements related to equity across implementation studies [9], and exclusivity and social injustice within the implementation science workforce perpetuated by structures making it harder for institutions to recruit and retain marginalized people (e.g., school-to-prison pipeline). Also, disparities exist for innovations being implemented and, if not adapted for marginalized populations, implementation may perpetuate the exclusion of marginalized communities and widen health inequities [6]. Similar to implementation studies, marginalized populations have historically been excluded from clinical trials and efficacy studies [10]. Further, innovations are often not designed nor as efficacious for marginalized populations [11,12,13]. Thus, the limitations of disparities in innovation development can be inherited by implementation science and likely perpetuated if the implementation does not systematically consider disparity determinants, cultural adaptations, and other ways to ensure health equity.

Outside the U.S., health equity and implementation research predominantly focus on a specific marginalized population, which is an important and valid path toward equity [9, 14,15,16]. Examples in low- and middle-income countries include measurement tools normed with participants from those countries [17], adapting innovations or delivery methods specifically to those populations [18] and reviewing or developing frameworks specific to those countries [14, 19, 20]. Although adaptations to local contexts are important, there remain gaps in applying principles of health equity to implementation research broadly, partly because locally adapted frameworks are not easily generalizable to other countries or contexts. The current charges to implementation researchers to ensure health equity in their efforts [6, 21] are not possible without adapting implementation determinant frameworks to first capture and understanding barriers to equitable implementation.

Implementation determinant frameworks with an equity focus are needed

Implementation science frameworks have been categorized into three types: determinant (establishing what factors determine or predict implementation success), process (clarifying how to address determinants to achieve implementation success), and evaluation (determining metrics and assessment to know when implementation success is achieved) [22]. Implementation determinant frameworks are key to inform study design and selection of strategies to match contextual needs; yet, we have only recently considered determinants unique to health inequities, starting with the Health Equity Implementation Framework [23]. We first piloted health equity domains within the context of a determinant framework as this type of framework represents the key first step to detecting (and eventually addressing) implementation disparities. If implementation researchers and practitioners could meaningfully and practically assess and understand the determinants of implementation disparities, this would allow them to adapt the innovation and implementation strategies for marginalized populations and detect health equity determinants as potential moderators for implementation success/failure [21]. Unfortunately, most implementation determinant frameworks have yet to be explicitly adapted for or tested within health equity efforts and any that do appear too vague to be used meaningfully [24].

Our prior work documented and piloted adaptations of one existing implementation determinant framework with three health equity domains to create the Health Equity Implementation Framework [23]. One may also use the Health Equity Implementation Framework in its entirety as an implementation determinant framework or use the three health equity domains as additions to another implementation determinant framework. Many researchers and practitioners have requested clarification of the Health Equity Implementation Framework domains for practical use. Damschroder argued that implementation frameworks must describe how domains are well-grounded in existing literature, provide clear definitions, and offer suggested validated implementation strategies [22]. Therefore, we review definitions of the domain of the Health Equity Implementation Framework in more depth than in prior work, showcase two applications of this determinant framework from the literature, and delineate steps to incorporate health equity domains in an implementation determinant framework, with sample measures and data collection tools for each domain.

Health Equity Implementation Framework

In the Health Equity Implementation Framework, we proposed determinants believed to predict successful and equitable implementation, seen in Fig. 1 [23]. These determinants are grouped under domains. We define domains as broad constructs relevant to implementation and health equity success. Within each domain are several determinants or specific factors that are measurable and, together in constellation with other determinants, clarify barriers, facilitators, moderators, or mediators to implementation and health equity success. This framework was developed for healthcare and clinical practice settings [25]. In the Health Equity Implementation Framework, we added three health equity domains to the Integrated Promoting Action on Research in Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework [26], which also proposes a process—facilitation—by which change in each domain would occur [25, 26]. The focus of this manuscript is on the three health equity domains, rather than facilitation, as science is still emerging on how implementation processes should be tailored or adapted to promote equity.

Domains typical in implementation determinant frameworks

Broad domains typical in implementation determinant frameworks focus on factors spanning multiple levels, including the individual (e.g., personal characteristics, actors of implementation, individuals receiving an innovation), organization (e.g., clinical service, school, department, factory), community (e.g., local government, neighborhood), system (e.g., school district, hospital system), and policy (e.g., state government, broader laws) [27]. These domains can be further specified, such as inner setting or outer setting within an organization [28]. Domains from i-PARIHS are the basis of the Health Equity Implementation Framework and include those typical in most implementation determinant frameworks [27]. Determinants within each domain act to enable or constrain implementation and each domain is briefly defined below.

Innovation

Innovation refers to the treatment, intervention, practice, or new “thing” to be implemented, adopted by providers and staff, and delivered to patients [29]. The innovation may be a program, practice, principle, procedure, product, pill, or policy [30].

Recipients

Recipients are individuals who influence implementation and those who are affected by its outcomes, both at the individual and collective team levels [26]. In healthcare, recipients are typically grouped into providers and other staff, and patients and caregivers.

Context

Context includes different micro, meso, or macro levels that correspond to inner and outer contexts [26]. Context can include factors such as resources, culture, leadership, and orientation to evaluation and learning. In this framework, the micro-level includes the local inner context (e.g., specific ward or clinic), whereas the meso includes the organization (e.g., hospital or medical center). The macro-level of outer context includes the wider healthcare system and effect this has on the other domains (e.g., United Kingdom National Health Service) [28].

Facilitation or process

There are processes by which barriers in implementation domains are solved or overcome, and strengths are harnessed to promote the use of an innovation in routine practice [28]. In i-PARIHS, facilitation is the “active ingredient” or process [31]. Facilitation involves implementation strategies that result in implementation coming to fruition [32, 33].

Domains known to affect health equity

The Health Equity Implementation Framework incorporates these domains known to affect health disparities and thus, equity: (1) culturally relevant factors, such as medical mistrust, demographics, or biases of recipients [34,35,36,37]; (2) clinical encounter or patient-provider interaction [38,39,40]; and (3) societal context including physical structures, economies, and social and political forces [41,42,43]. We added these three health equity domains, described below, from existing research that have clear, strong associations with disparities in health status, access to, quality of, or outcomes of healthcare, [44] or there is enough evidence to suggest determinants within these domains should be considered (e.g., [45]).

-

1.

Culturally relevant factors of recipients. Recipients in the implementation process are individuals who will be asked to offer or receive an innovation (e.g., patients, providers) [26]. Culturally relevant factors of recipients are characteristics unique to a group of people in the implementation effort (e.g., patients, staff, providers) based on their lived experience. Some examples of recipient factors that may be culturally relevant are implicit bias, socioeconomic status, race and/or ethnicity, immigrant acculturation, language, health literacy, health beliefs, or trust in the clinical staff or patient group [36, 37]. Demographic characteristics, such as socioeconomic status or race, are not inherently descriptive of one’s culture. Rather, the important takeaway is how living in the world with these factors shapes one’s culture and experience (e.g., living in impoverished neighborhoods, experiencing racism). We do not feel strongly that any demographic factor be categorized as a culturally relevant factor—the most important thing, from our view, is that implementation practitioners and scientists acknowledge these demographics among their recipient groups and consider how implementation may need to be adapted based on the lived experience of recipient groups. For instance, implementation practitioners and scientists should consider how implementation would need to change for those who have little formal education, are people of color, or are underinsured. Factors from patients and providers might attend to differences between, for example, age, pre-existing stereotypes, or lack of trust that could hinder the interaction [40]. Culturally relevant factors will vary by group, local context, and individuals. It is crucial that culturally relevant factors of recipients are considered as determinants or potential moderators in implementation success/failure when patients belong to a group experiencing a health or healthcare disparity.

-

2.

Clinical encounter (patient-provider interaction). This domain describes the transaction that occurs between patients and providers in healthcare appointments, where decisions concerning diagnoses and treatment are made, and providers administer care [46]. The clinical encounter is important to assess because there is a myriad of behaviors and perceptions during the clinical encounter that affect whether an innovation is offered by a provider and whether it is accepted by a patient. Behaviors will vary by innovation, context, and recipients and may be especially important for patients who experience health or healthcare disparities due to unequal power between them and providers. Factors to measure might be how recipients maneuver the conversation accordingly to achieve their individual and shared goals [40, 47]. It would also be important to capture unconscious or implicit bias from either recipient about the other recipient’s characteristics, such as race, weight, or perceived sexual orientation [48,49,50]. These unconscious biases may manifest in unhelpful behaviors during the encounter, such as dismissing someone’s concerns, interrupting the other person, or not smiling, touching, or making eye contact. Clinical encounters predict patient satisfaction, trust, and health outcomes; thus, it is crucial to assess and address what occurs during the clinical encounter, especially with regard to implementation disparities [47, 50,51,52].

-

3.

Societal context: economies, physical structures, and sociopolitical forces. This domain is similar to social determinants of health, yet also incorporates more upstream determinants (e.g., governance) that have been investigated less relative to mid- or downstream determinants (e.g., neighborhoods) [44]. Societal context includes three specific determinants: (1) economics, (2) physical structures, and (3) sociopolitical forces. In piloting the Health Equity Implementation Framework, societal context affected receipt of antiviral hepatitis C virus medicine for Black patients in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration [23].

Societal context may include historical or current discrimination against marginalized groups, such as racism, classism, or transphobia that may be formally or informally institutionalized within any organizational or local context. These factors usually occur in the broadest levels of the environment (e.g., province, nation), affecting the healthcare system, clinics, and recipients downstream. Many societal context determinants are interrelated, such as a policy affecting a physical structure. It is not as important to distinguish whether a factor is exclusively an economy, physical structure, social norm, or all three; rather, it is important these societal determinants are detected and addressed to ensure strategies address key drivers of societal inequities. Societal context may not be assessed comprehensively in one study or initiative, due to feasibility constraints, but they should be documented in formative evaluations/initial diagnostic assessments of the implementation problem.

Economies

There are four typical structures of economies including a traditional economy (i.e., mostly agricultural), market economy (i.e., firms and private interests control capital), command economy (i.e., government controls capital), and a mixed economy (combination of command and market) [53]. It is helpful to consider how economic structure affects access to resources for implementation. Market forces can be used to change demand for products deemed healthy or unhealthy, therefore driving policy implementation. Examples of market forces include taxes on tobacco, unhealthy food, and soft drinks, or food subsidy programs for women with low incomes [41].

Physical structures

Equity can be affected by how physical spaces, or “built environments,” are arranged and how transition between those spaces occurs for healthcare [41]. Physical structures include any factors where people have to physically go to get healthcare and what environmental elements people may be exposed to (e.g., privacy or lack thereof, what they see, what is emitted in the air and into their bodies). One example in healthcare settings is the type and quality of language translations of information displayed (e.g., flyers, waiting rooms)—whether it matches the language of patients served [54]. The location of the healthcare setting in a town or city is important in relation to where patients reside [54, 55], e.g., is it difficult for patients to get to the point of care? Another example is the implementation of one U.S. state’s naloxone standing order in which pharmacies could distribute naloxone without a prescription: 61.7% of retail pharmacies had naloxone available without a prescription [56]. However, naloxone availability was lower in neighborhoods with higher percentages of residents with public health insurance—a physical structure problem (lower availability of naloxone in some neighborhoods) interacting with an economic factor (public health insurance). This finding was particularly problematic due to an increased cost of naloxone for people on public health insurance as a result of the statewide mandate.

Sociopolitical forces

The third societal context describes social norms or political forces, which can include but are not limited to political support, laws, and social structures in which linkages between institutions perpetuate oppression, such as racism, misogyny, classism, or heterosexism [43, 57]. For instance, public health policies (e.g., fiscal, regulation, education, preventative treatment, and screening) demonstrate positive and negative effects on health disparities that occur across health domains (e.g., tobacco, food and nutrition, reproductive health services) [41]. As another example, a study examined U.S. state legislators’ behavioral health research-seeking practices and dissemination preferences and found significant variation between Democrats and Republicans, suggesting dissemination materials be tailored to different social norms for different groups [58].

Next, we showcase two examples of how implementation teams have used culturally relevant factors of recipients, patient-provider clinical encounter, and societal context as health equity domains in formative and process evaluations. Each example comes from different health service sectors and describes efforts focused on implementation disparities.

Conducting a formative needs assessment prior to implementation

The Health Equity Implementation Framework has been applied to guide a needs assessment for an implementation project aiming to reduce inequities in the provision and receipt of publicly funded services for individuals with developmental disabilities in the U.S. (Rieth SR, Dickson KS, Plotkin R, Corsello C, Ko J, Cook-Clark T, et al: An in-depth analysis of expenditures for Latinx individuals with developmental disabilities: Following the money and perspectives from the front line, in preparation). In 2016, the State of California Department of Developmental Services made funds available to address significant inequities in service expenditures for Latinx clients. In response, the San Diego Regional Center, the local agency coordinating and funding publicly-funded developmental disability services, initiated a partnership with local services and implementation researchers to identify inequity reduction targets and develop and implement an inequity reduction model. A mixed methods needs assessment was conducted to inform model development and implementation activities. Quantitative data included administrative data from the previous year. Qualitative data were gathered from focus groups with regional center case managers to identify key determinants of inequities from their perspectives.

The Health Equity Implementation Framework guided the identification of implementation determinants and the selection of data coding and analyses. Specifically, the framework informed the development of the qualitative codebook, including coding domains and definitions that were iteratively refined for this project. The framework guided subsequent integration of qualitative and quantitative data, including the use of qualitative themes to complement and expand quantitative findings. Preliminary findings indicate a significant impact of outer and inner context on inequities, including fit between patient recipient characteristics, culturally relevant factors, and characteristics of available innovations. Additional outer context factors, including sociopolitical factors and physical structures such as location (urban versus rural) also impact service utilization, including interactions with provider factors and innovation characteristics.

Conducting a process evaluation to categorize ongoing barriers/facilitators

In Toronto, Canada, legally sanctioned supervised consumption services (the innovation) are integrated within health centers; implementation has occurred and is ongoing. Supervised consumption services are for people who inject drugs to receive sterile injection equipment and inject under staff supervision. Staff educate on safer injecting, provide referrals to services, and can respond to overdoses, reducing transmission of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV) and overdose deaths. Researchers used ethnographic observation and individual semi-structured interviews with 24 patients who injected drugs in supervised consumption services at two community health centers, half of who were people of color or Indigenous to Canada [59]. After coding, researchers interpreted findings within domains of the Health Equity Implementation Framework.

Integrating legally sanctioned supervised consumption services within health centers (sociopolitical force) provided clients access to other health services, including dentistry and medical assistance that eliminated the need for a provider visit (characteristics of the innovation, organizational context). Patients appreciated having everything in one physical place (physical structure). One participant said the services allowed them to avoid meeting providers who were prejudice against drug use (sociopolitical force, provider culturally relevant factor).

Yet, there were barriers to implementation. Patients were uncomfortable being seen by peers using the center due to stigma about drug use (sociopolitical force). Spatial limitations at the center made it difficult to have privacy while injecting (physical structure). Patients preferred the center to be open all the time (organizational context), but there were not enough staff for that flexibility (healthcare system context). Ethnographic observation suggested standalone supervised consumption services were consistently busier than integrated services, potentially because some people felt uncomfortable in a healthcare setting (patient factor).

Methods

We completed a consensus process to clarify steps for incorporating a health equity lens into an implementation determinant framework, situated within the existing literature. We reviewed Moullin and colleagues’ ten suggested steps for incorporating frameworks into an implementation effort [60] and selected the five steps applicable to an implementation determinant framework (vs. evaluation or process frameworks). The first author (ENW) expanded those five steps from Moullin and colleagues [60] with steps on how to incorporate health equity domains and determinants. These steps were vetted with the authorship team through a process of oral discussions, reviewing written documents, and refining steps until all agreed. Next, our team created or aligned a table, tool, or example for more practical guidance on how each step could be executed.

Results

Applying health equity domains across an implementation effort

Below are suggested steps on how to use frameworks in an implementation effort [60] with a focus from our authorship team specifically on health equity in an implementation determinant framework.

Select a suitable framework or domains for an implementation disparity problem

If an implementation effort will focus on a health condition or marginalized population with documented health or healthcare disparities, we strongly suggest incorporating determinants from the three health equity domains into one’s preferred implementation framework or use the Health Equity Implementation Framework. If we do not assess or consider domains that promote or inhibit disparities, then we cannot expect to address them in a meaningful way, and we cannot build our scientific integration of health equity and implementation science to generalize across implementation efforts. To find an implementation determinant framework other than the Health Equity Implementation Framework that can be adapted for implementation disparities, pick a framework using an online webtool showcasing many implementation determinant frameworks (https://dissemination-implementation.org/) [61].

The Health Equity Implementation Framework can be adapted to any population or country where implementation disparities occur. The framework proposes determinants of inequitable implementation and a process (facilitation) by which to address determinants. The framework has not been used as a process or evaluation framework; thus, we cannot speak to the value of focusing on these domains in implementation processes or to these domains as evaluation outcomes.

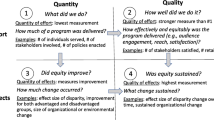

Determine implementation determinants

Assess which determinants are present in an implementation disparity and whether each determinant is a barrier (challenge) to improving equitable implementation or a facilitator (strength). Through formative evaluation to assess barriers and facilitators in each domain [62, 63] align qualitative interview guides, quantitative measures, and other assessment methods (e.g., participant observation, policy review) to the framework’s determinants. For qualitative and quantitative assessments of determinants, we present in Table 1 a variety of assessment methods and measures one might use to assess determinants within the Health Equity Implementation Framework. An illustrative example is given to showcase how others have assessed various determinants incorporated in the framework. Although Table 1 is not exhaustive, it is a robust reference and guide to consider certain measures, tools, or data sources for formative evaluation.

If one is using qualitative methods to determine some or all of the equitable implementation determinants, we provide examples of questions from qualitative interview guides we piloted that are aligned to domains of the Health Equity Implementation Framework (see Additional file 1). If this approach is used, the framework domains are then helpful for designing qualitative codebooks or templates for analysis. We provide a codebook for analysis we piloted that is aligned to the three health equity domains (see Additional file 2). The codebook for the health equity domains can be combined with codebooks of other determinant frameworks, such as Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [126].

Use domains to develop an implementation mechanistic process model or logic model

Determinants in the Health Equity Implementation Framework may directly influence the success and equity of an implementation effort or they may indirectly affect outcomes as mechanisms through which success or equity are enhanced. Using the three health equity domains added to an implementation determinant framework, one may develop theoretically driven hypotheses about which domains, or determinants within them, must change to lead to improved equity and implementation success [127]. These determinants are mechanisms. When working on an implementation disparity problem, this will ensure some mechanisms related to equity and implementation are investigated.

To understand the concept of mechanisms of implementation disparities, we consider a hypothetical example of an implementation disparity at one hospital where an evidence-based innovation is received mostly by White people with moderate or high incomes. In this example, the implementation disparity between patients of different races and incomes may be due to (1) the innovation was developed and tested in samples of mostly White people such that it is not acceptable to or effective for Black people (characteristic of the innovation), (2) providers do not offer the innovation as often to Black patients as they do to White patients (clinical encounter), (3) there may not be many Black or lower-income people served at the hospital (outer context), or (4) the hospital is not readily accessible via public transportation to people with lower incomes who do not have motor vehicles (physical structure). There may be some known or unknown determinant within any domain of the Health Equity Implementation Framework contributing to implementation disparities; perhaps providers have unconscious biases toward Black people (a factor within the cultural recipients domain) that lead to them offering the innovation less frequently to Black patients than to White (clinical encounter). The key factor to change would be unconscious bias to affect provider behavior and alter the clinical encounter. To the extent possible, one can hypothesize which factor is the lever for more equitable implementation—which of these factors, if changed, would result in the innovation being received by more people with lower incomes and more Black people at that hospital? These levers are mechanisms of implementation disparities (areas to change with implementation strategies) for more just and equitable delivery of healthcare. Consider these health equity determinants in developing a logic model to explain the implementation process, including its mechanisms of change.

Use framework determinants to conduct and tailor implementation

After formative evaluation or initial diagnosis of the implementation disparity is complete, the areas for change will become clear and implementation strategies will need to be selected and tailored to local context and recipients with careful attention to equity and justice. There are many existing ways to use information from formative evaluation to select and tailor implementation strategies [128,129,130]. To address implementation disparities, explicitly include determinants of inequity in selecting and tailoring strategies, as well as unique barriers that may prevent organizations from addressing these inequities. For example, there may be a need to use community- or patient-informed strategies to repair harm and build trust among patient recipients who have been and are marginalized in healthcare systems, improve cultural and structural competence at all levels of an organization, or continuously monitor reach between patient subgroups to detect change in disparities. Although some are focusing on equity more in using implementation strategies [33, 91, 99, 131], there is considerably more work to be done on this, and careful attention to equity elements is needed to tailor implementation.

As implementation progresses, an implementation plan will need to be adapted as determinants change. The Health Equity Implementation Framework can be useful for determining areas to assess repeatedly and thus, intervene on, throughout implementation. Doing so ensures an equity lens is applied throughout implementation and that implementation processes, such as planning, strategy use, and goal setting, are thoughtfully executed according to dynamic needs. Repeated assessments can be done informally through observations, consultations with recipients and leadership, or more formally through mixed methods, including ones mentioned in Table 1 and used previously in formative evaluation [63].

Writing implementation reports or findings

For documenting the results of an implementation effort, clarify how the Health Equity Implementation Framework or its three health equity domains were incorporated. For example, barriers and facilitators from formative evaluation may be presented by framework domains. As implementation progresses, a team may want to document key changes within domains from the Health Equity Implementation Framework, similar to how ongoing implementation barriers and facilitators were recorded for the study that examined the implementation of legally sanctioned supervised consumption services in Canada [59]. The mixed method approaches suggested earlier will provide key information to be reported, making clear why implementation was successful or not, and how certain strategies affected whether disparities in receipt, use, access to, or quality of an innovation were reduced [6].

Discussion

Disparities in healthcare occur in implementation outcomes and patient health outcomes. Implementation disparities are rooted in social injustice, exacerbated by multiple inputs, such as societal context, patient mistrust, provider bias, and poor patient-provider interactions. The three health equity domains presented in more depth here are key adaptations for implementation researchers and suggested to adapt one’s preferred implementation framework (e.g., EPIS) to incorporate an equity lens and account for inputs contributing to implementation disparities. Three health equity domains from the Health Equity Implementation Framework can be studied as determinants of implementation, as showcased in the application to services for developmental disabilities in California. We propose that an increased focus on health equity explicitly at multiple ecological levels in implementation science and practice will elucidate drivers of health inequities such as structural racism, heterosexism, and patriarchy. Thus, the discovery of these drivers of health inequities should necessitate implementation strategies to overcome or resolve such complex and oppressive structures. Future research should focus on implementation strategies (or other processes) used to address health equity determinants of unjust health inequities in our healthcare systems and societies.

We have only piloted the three health equity domains within the context of a determinant framework; however, they may be suitable as process or evaluation variables. As this framework evolves through implementation research and we have more data to inform its application, future considerations could include that some of these domains for determinants should also be outcomes of implementation disparity reduction efforts. For an implementation process framework that incorporates an equity lens, see frameworks proposed by Nápoles and Stewart [132] and Eslava-Schmalbach and colleagues [133]. For an implementation evaluation framework that incorporates an equity lens, see preliminary equity-focused implementation outcomes [133] and the proposed extension of the RE-AIM framework [134].

There are limitations to our framework and practical guidance presented here. We have piloted test many, but not all, the feasibility and acceptability of the steps we described using three health equity domains and measures in Table 1. However, we suggest these as starting places, and with confidence, as they all have entire bodies of science showcasing their relevance to health equity. We limited the application of this framework to healthcare settings, although it could be adapted to community or school settings. Although health equity can be incorporated across several determinant frameworks, we provided a detailed application of health equity domains tied to i-PARIHS. They have the potential for broader applications to other implementation science frameworks. This has not been piloted yet to our knowledge.

Conclusion

Implementation researchers and practitioners must adopt a health equity lens as foundational to any research-practice gap where inequity exists. Researchers might collect data on the feasibility, acceptability, and predictive utility of health equity determinants in this burgeoning area of implementation science. The Health Equity Implementation Framework is an implementation determinant frameworks to capture and understand barriers and facilitators to health inequities [23, 135]. The applications, steps, and tools in the manuscript are one step toward systematic integration of health equity and implementation science in frameworks.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- EPIS:

-

Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment

- i-PARIHS:

-

Integrated Promoting Action on Research in Implementation in Health Services

- U.S.:

-

United States

References

National Partnership for Action. National stakeholder strategy for achieving health equity. US Department of Health & Human Services. Rockville: Office of Minority Health; 2011.

Smedley B, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Assessing potential sources of racial and ethnic disparities in care: patient- and system-level factors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2003.

Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203.

Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Carpenter LA, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, Durkin MS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):493–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243.

Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am Assoc Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50:287–99.

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3.

Yapa HM, Bärnighausen T. Implementation science in resource-poor countries and communities. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0847-1.

Melgar Castillo A, Woodward EN, True G, Willging CE, Kirchner JE. Examples and Challenges of Engaging Consumers in Implementation Science Activities: An Environmental Scan. Oral symposium at the 13th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation. Washington D.C.; 2020.

McNulty M, Smith JD, Villamar J, Burnett-Zeigler I, Vermeer W, Benbow N, et al. Implementation research methodologies for achieving scientific equity and health equity. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S1.83.

Polo AJ, Makol BA, Castro AS, Colón-Quintana N, Wagstaff AE, Guo S. Diversity in randomized clinical trials of depression: a 36-year review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;67:22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.004.

Baumann AA, Powell BJ, Kohl PL, Tabak RG, Penalba V, Proctor EK, et al. Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent-training: a systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;53:113–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.025.

Windsor LC, Jemal A, Alessi EJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy: a meta-analysis of race and substance use outcomes. Cult Diver Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2015;21(2):300–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037929.

Hays PA. Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive–behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychol. 2009;40(4):354–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016250.

Harding T, Oetzel J. Implementation effectiveness of health interventions for indigenous communities: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2019;14 Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-019-0920-4 [cited 2019 3 Sep].

Turcotte-Tremblay A-M, Spagnolo J, De Allegri M, Ridde V. Does performance-based financing increase value for money in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-016-0103-9.

Tougher S, Dutt V, Pereira S, Haldar K, Shukla V, Singh K, et al. Effect of a multifaceted social franchising model on quality and coverage of maternal, newborn, and reproductive health-care services in Uttar Pradesh, India: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e211–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30454-0.

Bergström A, Skeen S, Duc DM, Blandon EZ, Estabrooks C, Gustavsson P, et al. Health system context and implementation of evidence-based practices—development and validation of the Context Assessment for Community Health (COACH) tool for low- and middle-income settings. Implement Sci. 2015;10 Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0305-2 [cited 2020 7 Jan].

Lauria ME, Fiori KP, Jones HE, Gbeleou S, Kenkou K, Agoro S, et al. Assessing the Integrated Community-Based Health Systems Strengthening initiative in northern Togo: a pragmatic effectiveness-implementation study protocol. Implement Sci. 2019;14 Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-019-0921-3 [cited 2020 7 Jan].

Nabyonga Orem J, Bataringaya Wavamunno J, Bakeera SK, Criel B. Do guidelines influence the implementation of health programs?—Uganda’s experience. Implement Sci. 2012;7 Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-7-98 [cited 2020 7 Jan].

Means AR, Kemp CG, Gwayi-Chore M-C, Gimbel S, Soi C, Sherr K, et al. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0.

DuMont K, Metz A, Woo B. Five recommendations for how implementation science can better advance equity. Acad Health Blog. 2019; Available from: https://www.academyhealth.org/blog/2019-04/five-recommendations-how-implementation-science-can-better-advance-equity. [cited 2019 May 20].

Damschroder LJ. Clarity out of chaos: use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:S0165178119307541.

Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal SS, Kirchner JE. The Health Equity Implementation Framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0861-y.

Spitzer-Shohat S, Chin MH. The “waze” of inequity reduction frameworks for organizations: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):604–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04829-7.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0.

Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2015;11 Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2 [cited 2017 21 Mar].

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers D, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Curran GM. Implementation science made too simple: a teaching tool. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00001-z.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Ann Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215.

Harvey G, Kitson A. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. New York: Routledge; 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203557334.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4328074/ [cited 2016 26 Feb].

Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller C, Smith JL, Oliver KA, Kim B, et al. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare implementation facilitation training manual (version 3). Veterans Health Administration, Behavioral Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI); 2020. Available from: https://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/implementation.cfm

LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(6):2093–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x.

Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628.

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4.

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Policies and social values. In: Woolf SH, Aron L, editors. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK154493/. [cited 2020 Apr 23].

van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00338-X.

Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Wilson I, et al. Differences in patient–provider communication for Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic White patients in HIV care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):682–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1310-4.

Street RL. Communication in medical encounters: an ecological perspective. Handbook of Health Communication. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003.

Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Todd A, McNamara C, Huijts T, Bambra C. The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high-income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):869. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5677-1.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6.

Watson DP, Adams EL, Shue S, Coates H, McGuire A, Chesher J, et al. Defining the external implementation context: an integrative systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3046-5.

Palmer RC, Ismond D, Rodriquez EJ, Kaufman JS. Social determinants of health: future directions for health disparities research. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S70–1. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304964.

Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, Waite R, Whitfield-Harris L, Deatrick JA. Patient–provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethnicity Health. 2009;14(1):107–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850802227031.

Dieppe P, Rafferty A-M, Kitson A. The clinical encounter - the focal point of patient-centred care. Health Expect. 2002;5(4):279–81. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00198.x.

Street RL, Liu L, Farber NJ, Chen Y, Calvitti A, Zuest D, et al. Provider interaction with the electronic health record: the effects on patient-centered communication in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):315–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.004.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558.

Sabin JA, Marini M, Nosek BA. Implicit and explicit anti-fat bias among a large sample of medical doctors by BMI, race/ethnicity and gender. Plos One. 2012;7 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3492331/ [cited 2016 18 Feb].

Li C-C, Matthews AK, Aranda F, Patel C, Patel M. Predictors and consequences of negative patient-provider interactions among a sample of African American sexual minority women. LGBT Health. 2015;2(2):140–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0127.

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33.

Bankoff SM, McCullough MB, Pantalone DW. Patient-provider relationship predicts mental and physical health indicators for HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):762–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313475896.

Swedberg R. Principles of economic sociology: Princeton Univ Press; 2009. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcm4g75.

Brach C, Fraserirector I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(1_suppl):181–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S09.

Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032.

Egan KL, Foster SE, Knudsen AN, Lee JGL. Naloxone availability in retail pharmacies and neighborhood inequities in access. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58:699–702.

Bruns EJ, Parker EM, Hensley S, Pullmann MD, Benjamin PH, Lyon AR, et al. The role of the outer setting in implementation: associations between state demographic, fiscal, and policy factors and use of evidence-based treatments in mental healthcare. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0944-9.

Purtle J, Dodson EA, Nelson K, Meisel ZF, Brownson RC. Legislators’ sources of behavioral health research and preferences for dissemination: variations by political party. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(10):1105–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800153.

Bardwell G, Strike C, Mitra S, Scheim A, Barnaby L, Altenberg J, et al. “That’s a double-edged sword”: exploring the integration of supervised consumption services within community health centres in Toronto, Canada. Health Place. 2020;61:102245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102245.

Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick N, Albers B, Nilsen P, Broder-Fingert S, et al. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00023-7.

ACCORDS Dissemination and Implementation Science Program at the University of Colorado, Denver, Dissemination and Implementation Research Core (DIRC) at the Washington University Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, Dissemination and Implementation Science Center (DISC) at UC San Diego. Dissemination and Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice. 2021.

Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davis D. editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. 2nd ed. Wiley: West Sussex; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118525975.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(S2):S1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0267-9.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03068.x.

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ, Stirman SW. Adaptation in dissemination and implementation science. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 285–300.

Scott SD, Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni N, Bize R, Rodgers W. Factors influencing the adoption of an innovation: an examination of the uptake of the Canadian Heart Health Kit (HHK). Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-3-41.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-22.

Lukas CV, Meterko MM, Mohr D, Seibert MN, Parlier R, Levesque O, et al. Implementation of a clinical innovation: the case of advanced clinic access in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Ambul Care Manage. 2008;31(2):94–108. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAC.0000314699.04301.3e.

Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006.

Rounds K, Mcgrath BB, Walsh E. Perspectives on provider behaviors: a qualitative study of sexual and gender minorities regarding quality of care. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44(1):99–110. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2013.44.1.99.

Quiñones TJ, Woodward EN, Pantalone DW. Sexual minority reflections on their psychotherapy experiences. Psychother Res. 2017;27(2):189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1090035.

Hall J, Roter D, Junghans B. Doctors talking with patients—patients talking with doctors: improving communication in medical visits. Clin Exp Optom. 1995;78(2):79–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1444-0938.1995.tb00792.x.

Blair IV, Steiner JF, Havranek EP. Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: where do we go from here? Perm J. 2011;15:71–8.

Kitts RL. Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex. 2010;57(6):730–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2010.485872.

Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among US primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1256–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1.

Neville HA, Lilly RL, Duran G, Lee RM, Browne L. Construction and initial validation of the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS). J Counsel Psychol. 2000;47(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.59.

Kawulich BB. Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method [81 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2005;6(2):43. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502430.

Drummond K, Painter JT, Curran G, Stanley R, Gifford AL, Rodriguez-Barradas M, et al. HIV patient and provider feedback on a telehealth collaborative care for depression intervention. AIDS Care. 2017;29(3):290–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1255704.

Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. Disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Ann Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–52.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2016 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/index.html?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term=

Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, Schulz PJ. The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. Antonietti A, editor. Plos One. 2015;10:e0145455.

Young M, Klingle RS. Silent partners in medical care: a cross-cultural study of patient participation. Health Commun. 1996;8(1):29–53. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc0801_2.

Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, Saad N, Niculescu A, Powell P. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor–patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129–35. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.006616.

Williamson LD, Bigman CA. A systematic review of medical mistrust measures. Patient Educ Counsel. 2018;101(10):1786–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.007.

Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5.

Stagliano V, Wallace LS. Brief health literacy screening items predict newest vital sign scores. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):558–65. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.130096.

Campón RR, Carter RT. The Appropriated Racial Oppression Scale: development and preliminary validation. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2015;21(4):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000037.

Woodward EN, Cunningham JL, Flynn AWP, Mereish EH, Banks RJ, Landes SJ, et al. Sexual minority men want provider behavior consistent with attitudes and norms during patient-provider interactions regarding HIV prevention. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:354–67.

Willging CE, Salvador M, Kano M. Pragmatic help seeking: how sexual and gender minority groups access mental health care in a rural state. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):871–4. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.871.

Aarons GA. Transformational and transactional leadership: association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. PS. 2006;57(8):1162–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1162.

Mora Pinzon M, Myers S, Jacobs EA, Ohly S, Bonet-Vázquez M, Villa M, et al. “Pisando Fuerte”: an evidence-based falls prevention program for Hispanic/Latinos older adults: results of an implementation trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19. Available from: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1273-1. [cited 2019 Sep 25]

Fukui S, Rapp CA, Goscha R, Marty D, Ezell M. The perceptions of Supervisory Support Scale. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(3):353–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0470-z.

Herscovitch L, Meyer JP. Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):474–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474.

Holt DT, Armenakis AA, Feild HS, Harris SG. Readiness for organizational change: the systematic development of a scale. J Appl Behav Sci. 2007;43(2):232–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886306295295.

Fernandez ME, Walker TJ, Weiner BJ, Calo WA, Liang S, Risendal B, et al. Developing measures to assess constructs from the Inner Setting domain of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0736-7.

Akhavan S, Tillgren P. Client/patient perceptions of achieving equity in primary health care: a mixed methods study. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0196-5.

Blakeman T, Protheroe J, Chew-Graham C, Rogers A, Kennedy A. Understanding the management of early-stage chronic kidney disease in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(597):e233–42. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X636056.

Weech-Maldonado R, Dreachslin JL, Brown J, Pradhan R, Rubin KL, Schiller C, et al. Cultural competency assessment tool for hospitals: evaluating hospitals’ adherence to the culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(1):54–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0b013e31822e2a4f.

Spitzer-Shohat S, Shadmi E, Goldfracht M, Key C, Hoshen M, Balicer RD. Evaluating an organization-wide disparity reduction program: understanding what works for whom and why. Akinyemiju TF, editor. Plos One. 2018;13:e0193179.

Gagnon M-P, Attieh R, Ghandour EK, Légaré F, Ouimet M, Estabrooks CA, et al. A systematic review of instruments to assess organizational readiness for knowledge translation in health care. Jeyaseelan K, editor. Plos One. 2014;9:e114338.

Montesanti SR, Abelson J, Lavis JN, Dunn JR. Enabling the participation of marginalized populations: case studies from a health service organization in Ontario, Canada. Health Promot Int. 2017;32:636–49.

Kano M, Silva-Banuelos AR, Sturm R, Willging CE. Stakeholders’ recommendations to improve patient-centered “LGBTQ” primary care in rural and multicultural practices. J Ame Board Fam Med. 2016;29(1):156–60. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150205.

Curran GM, Mukherjee S, Allee E, Owen RR. A process for developing an implementation intervention: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3. Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-3-17. [cited 2019 Apr 19]

Aarons GA, Green AE, Willging CE, Ehrhart MG, Roesch SC, Hecht DB, et al. Mixed-method study of a conceptual model of evidence-based intervention sustainment across multiple public-sector service settings. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0183-z.

Institute of Medicine C on CM for BH at LC. Vital signs: core metrics for health and health care progress. Blumenthal D, Malphrus E, Michael McGinnis J, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2015. p. 19402. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/19402. [cited 2020 May 13]

Human Rights Campaign. Healthcare Equality Index. Available from: https://www.hrc.org/hei. [cited 2020 May 19]

Kwon E, Park S, McBride TD. Health insurance and poverty in trajectories of out-of-pocket expenditure among low-income middle-aged adults. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4332–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12974.

Sabia JJ. Minimum wages and gross domestic product. Contemp Econ Policy. 2015;33(4):587–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12099.

Sahin K. Measuring the economy: GDP & NIPAs. Hauppauge: Nova Science; 2009.

Autor D, Manning A, Smith C. The contribution of the minimum wage to U.S. wage inequality over three decades: a reassessment. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, INC; 2014.

Baily MN, Okun AM. The battle against unemployment and inflation: problems of the modern economy. New York: W.W. Norton and Company; 1965.

Perloff HS. Interrelations of state income and industrial structure. Rev Econ Stat. 1957;39(2):162. https://doi.org/10.2307/1928533.

Gupta AS. Determinants of tax revenue efforts in developing countries. Washington: The International Monetary Fund; 2007

Van Wijnbergen S. Interest rate management in LDC’s. J Monetary Econ. 1983;12(3):433–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(83)90063-6.

Liu B-C. Economic base and economic structure growth: quantitative and qualitative measures; 1974. p. 6.

Soder N, Steinberg SL. Community currency: an approach to economic sustainability in our local bioregion. Arcata: Humboldt State University; 2008. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2148/347

LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D. Place, Not race: disparities dissipate in southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Affairs. 2011;30(10):1880–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0640.

Lyons T, Shannon K, Pierre L, Small W, Krüsi A, Kerr T. A qualitative study of transgender individuals’ experiences in residential addiction treatment settings: stigma and inclusivity. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0015-4.

Beyer KMM, Zhou Y, Matthews K, Bemanian A, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. New spatially continuous indices of redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending: links to survival after breast cancer diagnosis and implications for health disparities research. Health & Place. 2016;40:34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.014.

Rabinowitz P. Chapter 3: Section 21. Windshield and walking surveys. Lawrence: Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas; 2020. Available from: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/windshield-walking-surveys/main

Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, Hooley C, Mazzucca S, Lewis CC, et al. Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w.

Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A, Potter F, Sharma A, Knopov A, et al. The relationship between structural racism and black-white disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(2):106–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2017.12.002.

Mizen LA, Macfie ML, Findlay L, Cooper S-A, Melville CA. Clinical guidelines contribute to the health inequities experienced by individuals with intellectual disabilities. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-42.

Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Nolen E, et al. An updated protocol for a systematic review of implementation-related measures. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0728-3.

Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, Gilbert KL, editors. Racism: science & tools for the public health professional. American Public Health Association; 2019. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/book/10.2105/9780875533049. [cited 2020 May 28]

CFIR Research Team. Consolidated framework for implementation research. 2020. Available from: https://cfirguide.org/constructs/

Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Walsh-Bailey C, Lyon AR, Beidas R, Mittman B, et al. A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-00983-3.

Fernandez ME, ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. 2019;7:158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158.

Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6.

Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Parker LE, Gordon NP, Hickey SC, Oken C, et al. Impacts of evidence-based quality improvement on depression in primary care: a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00549.x.

Varcoe C, Bungay V, Browne AJ, Wilson E, Wathen CN, Kolar K, et al. EQUIP Emergency: study protocol for an organizational intervention to promote equity in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19 Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4494-2. [cited 2019 Oct 16].

Nápoles AM, Stewart AL. Transcreation: an implementation science framework for community-engaged behavioral interventions to reduce health disparities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18 Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-018-3521-z. [cited 2019 Jan 9].

Eslava-Schmalbach J, Garzón-Orjuela N, Elias V, Reveiz L, Tran N, Langlois EV. Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (EquIR). Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0984-4.

Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134.

Yancey A, Glenn BA, Ford CL, Bell-Lewis L. Dissemination and implementation research among racial/ethnic minority and other vulnerable populations. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science into Practice. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. p. 449–70.

Acknowledgements

Drs. Dickson and Woodward are fellows from the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH08091607). We thank Ross Brownson and Sarabeth Broder-Fingert for their continued encouragement and consultation.

Thank you to Amber D. Haley for the astute and generous consultation on the codebook template.

Funding

This work was in part supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH115100; PI: Dickson). Dr. Singh was also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Medical Research Service of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, and the Department of Veterans Affairs South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. This work was in part supported by Career Development Award Number IK2 HX003065 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (Dr. Woodward).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ENW conceptualized the manuscript, provided guidance on the literature for implementation and health equity domains for Table 1, prepared and refined all usable tools (additional files), and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript and all applications. RSS was a major contributor in writing the manuscript and preparing Table 1. PN contributed to the writing definitions of implementation and health equity domains and an application from the literature, literature searching, and writing of Table 1 and the conclusion. AMC contributed to the writing of defining implementation and health equity domains and also conducted literature searches and writing of Table 1. KSD helped conceptualize the purpose of the manuscript, prepared and wrote one application from current literature, and edited the writing of the manuscript. JEK significantly refined the conceptualizations of the manuscript and edited the writing of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Health Equity Implementation Framework Interview Guide: Three Health Equity Domains Only.

Additional file 2:

Qualitative Codebook of the Three Health Equity Domains from Health Equity Implementation Framework.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Woodward, E.N., Singh, R.S., Ndebele-Ngwenya, P. et al. A more practical guide to incorporating health equity domains in implementation determinant frameworks. Implement Sci Commun 2, 61 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00146-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00146-5