Abstract

The aim of this paper is to study the free convection boundary-layer flow with heat generation and variable fluid properties past a vertical plate. We incorporated the heat generation and variable viscosity are the exponential decay form and thermal conductivity is the linear form in the governing equation. Using similarity transformations, the governing coupled non-linear partial differential equations are transformed into a system of coupled non-linear ordinary differential equations and then solved using Maple symbolic software to execute the computations via dsolve. The effects of the temperature-dependent viscosity, the wall velocity power index, the thermal conductivity, the wall temperature parameter, and the Prandtl number on the flow and temperature fields are presented. The skin friction and the wall temperature gradient are also presented for different values of the physical parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For a long time, a vital subject in fluid dynamics is the problem of steady and unsteady laminar flow over a permeable surface because of its worth from both theoretical and viable point of view and has been studied in detail. It also has abundant applications in engineering and technological processes, such as petroleum industries, groundwater flows, the expulsion of a polymer sheet from a dye, and boundary layer control. The heat transfer mechanisms with non-uniform heat source/sink are an important topic for current researchers due to its comprehensive applications in the fields of physics and engineering. There are various industrial and engineering applications involving non-uniform heat source/sink, for example, nuclear power plants, aircraft, gas turbines, satellites, missiles, polymer industry, biomedicine, and processes concerning high temperature. Mohammadein and El-shear [1] revealed the effect of variable permeability on both free and forced convection. They reported the results of both uniform permeability and variable permeability cases. Later, Seddek and Salma [2] publicized the MHD boundary layer flow attribute of temperature-dependent viscosity and thermal conductivity. Reddy et al. [3] deliberated the numerical analysis for variable viscosity and thermal conductivity across a vertical porous plate. Consequently, several hypothetical and practical features of the flow and heat transfer with regards to power-law fluids have been examined by numerous researchers [4,5,6]. Further, a notable number of various studies has been carried out by innumerable researchers on electromagneto-hydrodynamic viscoelastic fluid [7,8,9].

Problems of the dynamic world led to inquire about analytical and numerical techniques to find out the deserved solutions of highly nonlinear and complex models. Although advancement in programming (like Mathematica, Matlab, Maple, C++, and Java) facilitate to solve such heavy, time-consuming ODEs/PDEs problems, yet it is the focused field for the researcher to erect and scan advance techniques that evaluate results of the nonlinear equations having multiple parameters arising from nature. In literature, the running techniques are the variational iteration method (VIM) [10], homotopy analysis method (HAM) [11], differential transform method (DTM) [12], and finite element method (FEM) [13]. The spectral relaxation method [14] and spectral perturbation method [15] have secured importance these days. Recently, several authors [16,17,18,19,20] have studied different flow parameters considering different fluid flows over different geometries.

There are a couple of reviews in the appurtenant literature concerning the numerical investigation of power-law fluid flow with internal heat generation generated by vertical or di surfaces [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. To the best knowledge of the authors, not many studies have been conducted on the flow of these fluids by considering the impacts of non-uniform heat source/sink, exponential variable viscosity, and thermal conductivity in mathematical model with a Lie group transformation approach. The innovation of this review is the computation of multiple solutions for such kind of physical model for the first time. So, in this article, we simulate free convection flow of over vertical plate.

Influenced by the abovementioned literature, the objective of our study is to explore the effects of internal heat generation on steady, free convective and variable fluid properties past a vertical plate. The effect of exponential variable viscosity and thermal conductivity is also taken into account. The crux of the present study is the discussion of internal heat generation caused by the momentum diffusion. Hence, an effective approach namely Maple symbolic software via dsolve has been adopted for simulations of leading non-linear system. Several plots are assembled to present the effects of involved pertinent parameters on momentum and thermal boundary layers. The equation governs the flow phenomena are solved using Maple symbolic software [29] to execute the computations via dsolve.

Governing equations with a similarity

We consider the flow of an incompressible, viscous fluid with the plane y = 0 considering variable viscosity and thermal conductivity. Figure 1 demonstrates a physical illustration of the flow model past a vertical surface that is designed for the present study. In the flow geometry, the vertical plate is fixed along the x-direction and the fluid is assumed to flow with the plate; the y-axis is taken exactly normal to it. A constant uniform temperature Tw which is greater than T∞ is maintained by the plate. The vertical surface moving continually in the positive x-direction with a velocity u = U∞.with the above assumptions the basic equations for steady flow are the corresponding equations, under the above assumptions, describing the two-dimensional viscous fluid motion, are given by the model of Dinesh et al. [30] leading to

The boundary conditions of the problem are

where q′′′ is the exponential form of internal heat generation which is defined by

Furthermore, by introducing a dimensional stream function ψ defined into Eqs. (1)–(4), we have

then we have

From Eq. (2)

From Eq. (3)

The boundary conditions (4) become

Lie group transformation

The solution of the system of non-similar partial differential Eqs. (5)–(6) subject to the boundary conditions (7) is analytically not possible. Numerical methods are required. However, even with powerful algorithms, the equations remain challenging and expensive also. Therefore, it is necessary to transform these into self-similar ODEs using Lie group transformations (see [31,32,33,34,35]). This effectively reduces the number of independent variables of the governing partial differential equations. Lie algebra is a powerful analytical approach based on continuous symmetry of mathematical structures and objects which has found many uses in modern theoretical physics and applied mathematics. This theory provides a new methodology for analyzing the continuous symmetries of governing equations of many fluid dynamic systems including non-Newtonian transport phenomena. Defining:

Substituting (8) into (5) and (6), we get

and

The transformed Eqs. (9) and (10) are invariant under the Lie group of transformation if the following relations among the transform parameters are satisfied.

and

and the boundary conditions we obtain at y → ∞

If we insert (13) into the scaling (8), the set of transformations reduces to a one-parameter group of transformations given by

Expanding Eq. (14) by Tailor’s method and the remaining terms up to O (ε2) of the one-parameter group, we further get

From Eq. (15), one can easily deduce the set of transformation in the form of the following characteristic equations:

Integrating the subsidiary equations (16),

we get

or

From the subsidiary equations

we get dθ = 0,that is θ(η)= constant=θ(say).

Also integrating the equation \( \frac{d x}{x{\alpha}_1}=\frac{d\psi}{\frac{1}{2}\psi {\alpha}_1}, \)

we get \( \frac{\psi }{x^{\frac{1}{2}}}= \) constant\( =\sqrt{u_{\infty}\nu }f\left(\eta \right) \)(say),

i.e., \( \psi =\sqrt{u_{\infty}\nu }{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}f\left(\eta \right) \)

or

Thus, the new similarity transformations are obtained as follows: \( \eta =y\sqrt{\frac{u_{\infty }}{\nu x}},\psi =\sqrt{u_{\infty}\nu x}f\left(\eta \right),\theta =\theta \left(\eta \right) \)

We introduce the following transformations

Using the above Eq. (17), the transformed equations yield the following transformed, dimensionless system of ordinary differential equations:

where Pr = υ/α is the Prandtl number, c = 0 or 1 corresponding to with and without internal heat generation.

The boundary conditions are converted to:

Numerical solution

Equations (18) and (19) which are self-similar nonlinear two-point boundary value problem has been solved using Maple via dsolve under boundary conditions (20). This is a very vigorous, legitimate computational algorithm with excellent convergence potentiality. This code has been used by many authors to acquire numerical solutions.

Results and discussion

We solve Eqs. (18) and (19) subject to boundary conditions (20) using the dsolve routine from MAPLE. The numerical solutions are obtained for various values of the parameters such as Prandtl number Pr, viscosity variation parameter β1, thermal diffusivity parameter β2, and temperature exponent parameter a with and without internal heat generation (IGH). We examined our result for positive and negative values of β1 the viscosity of the fluid such as water and lubrication oils for positive values of viscosity while for negative values of β1 the viscosity of the air. From the above discussions, the range of variations of the parameters of the flows β1 and β2 can be taken as follows [36]:

- 1)

For air: −0.7 ≤ β1 ≤ 0, 0 ≤ β2 ≤ 6

- 2)

For water: 0 ≤ β1 ≤ 0.6, 0 ≤ β2 ≤ 0.12

- 3)

For lubricants: 0 ≤ β1 ≤ 3, − 0.1 ≤ β2 ≤ 0

The effects of the physical parameters on the skin friction coefficient and wall temperature gradient for the variable viscosity and thermal conductivity parameter with and without IHG are presented in Table 1. From this table, it is seen that increasing viscosity parameter is to increase the skin friction and rate of heat transfer in both cases (with and without IHG). On the other hand, with increasing thermal conductivity parameter is to increase skin friction and rate of heat transfer for a negative value of viscosity parameter (i.e., gases) but opposite behavior is shown for the positive value of viscosity parameter (i.e., fluid).

The effect of changes in the viscosity parameter β1 = − 0.7, − 0.3, 0 and β1 = 0.1, 0.4, 0.6 on velocity and temperature profiles against η with Pr = 1, β2 = 1, a = 1 and without internal heat generation is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. From Fig. 2, it is observed that an increase in the viscosity parameter causes an increase in the velocity profile. Viscosity parameter is inversely proportional to dimensionless viscosity as an exponential form which describes Eq. (17). Therefore, an increase in viscosity parameter results to a decrease in dimensionless viscosity and in turn a decrease in viscous forces which oppose the fluid motion. This translates to inertia forces dominating viscous forces and hence fluid accelerates. It is noticed that the velocity profiles have no significant effect on the presence and absence of internal heat generation. Figure 3 describes the effects of changes in the viscosity parameter β1 on the temperature distribution. An increase in the viscosity parameter β1 causes a decrease in the temperature profile. This is attributed to a decrease in dimensionless viscosity translating into a decrease in viscous forces. These smaller viscous forces result in reduced friction between the fluid and the surface and thus decrease in the dissipation of heat within the boundary layer. Also, internal heat generation induced more flow than that of without internal heat generation for temperature distribution.

Figure 4 illustrates the influence of variable thermal conductivity parameter β2 on velocity and temperature profiles. We observed that fluid velocity induces with variable thermal conductivity. We also observed that the fluid temperature enhancement for increasing values of variable thermal conductivity parameter. It is verified that by increasing β2, kinetic energy of fluid particles increases which escalate intensifies in temperature.

Figure 5 describes the velocity and temperature profile with various values of power exponent parameter a. The value of a = 0 corresponds to uniform surface temperature, whereas a = 0.5 correspond to uniform surface flux and a = 1 correspond to uniform wall temperature. We observed that velocity profile and temperature distribution decreases with increasing values of power exponent parameter a. this effect is more significant for temperature profile than that of the velocity profile. Also, internal heat generation induced more flow than that of without internal heat generation for temperature distribution but there is no significant impact for velocity profile.

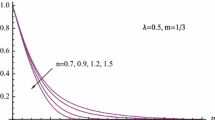

Figure 6 describes the velocity and temperature profile with various values of Prandtl number with and without internal heat generation. For all the cases, we see that velocity and temperature profiles decrease with the increase in the Prandtl number for all types of heat generation. Physically, when Pr = υ/α increases, α decreases, i.e., thermal diffusivity of fluid decreases. Hence, the heat flow through fluid decreases as Pr increases. Also, internal heat generation induced more flow than that of without internal heat generation, i.e., the mechanical strength in the fluid motion is increased. Note that temperature has a significant impact due to the Prandtl number.

Conclusion

In this paper, the effect of internal heat generation on free convective power-law variable temperature considering exponential variable viscosity and thermal conductivity past a vertical plate is analyzed. Few of the findings are as follows:

- 1)

Fluid velocity induced with variable viscosity parameter but the fluid temperature reduced for increasing values of viscosity parameter.

- 2)

The effect of variable thermal conductivity parameter is to enhance the temperature in the flow region and is reversed in the case of the wall temperature parameter.

- 3)

The fluid velocity and temperature profiles decrease with the increase in the Prandtl number.

- 4)

The effect of internal heat generation is to induce more flow than that of without internal heat generation for temperature distribution but there is no significant impact for all velocity profiles.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Mohammadein, A.A., El-shaer, N.A.: Influence of variable permeability on combined free and forced convection flow past a semi-infinite vertical plate in saturated porous medium. Heat. Mass. Transf. 40, 341–346 (2004)

Seddek, M.A., Salama, F.A.: The effects of temperature dependent viscosity and thermal conductivity on unsteady MHD convective heat transfer past an infinite porous moving plate with variable suction. J. Comput. Mat. Sci. 40, 186–192 (2007)

Reddy, M.G., Reddy, N.B., Reddy, B.R.: Unsteady MHD convective heat and mass transfer flow past a semi-infinite vertical porous plate with variable viscosity and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 5(6), 1–14 (2009)

Vajravelu, V.: Effects of variable properties and internal heat generation on natural convection at a heated vertical plate in air. Numerical Heat Transf. 3(3), 345–356 (1980)

Mahmoud, M.A.: Variable viscosity effects on hydromagnetic boundary layer flow along a continuously moving vertical plate in the presence of radiation. Appl. Math. Sci. 1(17), 799–814 (2007)

Poonia, M., Bhargava, R.: Heat transfer of convective MHD viscoelastic fluid along a moving inclined plate with power-law surface temperature using Finite Element Method. Multidiscipline Model Mat. Struct. 10(1), 106–121 (2014)

Othman, M.I.A., Ezzat, M.A.: Electromagneto-hydrodynamic instability in a horizontal viscoelastic fluid layer with one relaxation time. Acta Mechanica. 150(1-2), 1–9 (2001)

Othman, M.I.A., Zaki, S.A.: The effect of thermal relaxation time on electro hydro-dynamic viscoelastic fluid layer heated from below. Can. J. Phys. 81, 779–787 (2003)

Othman, M.I.A.: On the possibility of overstable motion of a rotating viscoelastic fluid layer heated from below under the effect of magnetic field with one relaxation time. Mech. Mech. Eng. 7(1), 41–52 (2004)

Hassan, K, Ganji, D.D, Sadighi, A: Application of variational iteration and homotopy perturbation methods to nonlinear heat transfer equations with variable coefficients. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications: An Int. J. Comput. Method. 52(1), 25-42 (2007)

Liao, S.J.: A short review on the homotopy analysis method in fluid mechanics. J. Hydrodynamics. 22(5), 882–884 (2010)

Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., Bai, Y.: Unsteady flow and heat transfer of power-law nanofluid thin film over a stretching sheet with variable magnetic field and power-law velocity slip effect. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 70, 104–110 (2017)

Poonia, M., Bhargava, R.: Finite element solution of MHD power-law fluid with slip velocity effect and non-uniform heat source/sink. Comput. Appl. Math. 37(2), 1737–1755 (2018)

Haroun, N.A.H., Sibanda, P., Mondal, S., Mosta, S.S.: On unsteady MHD mixed convection in a nanofluid due to a stretching/shrinking surface with suction/injection using the spectral relaxation method. Boundary Value Probs. 24, 1–17 (2015)

Agbaje, T.M., Mosta, S.S., Mondal, S., Sibanda, P.: A large parameter spectral perturbation method for nonlinear systems of partial differential equations that models boundary layer flow problems. Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer. 9, 36 (2017). https://doi.org/10.5098/hmt.9.36

Oyelakin, I.S., Mondal, S., Sibanda, P.: A multi-domain spectral method for non-Darcian mixed convection flow in a power-law fluid with viscous dissipation. Phys Chem Liquids. 56(6), 771–789 (2018)

Goqo, S.P., Mondal, S., Sibanda, P., Mosta, S.S.: Efficient multi-domain bivariate spectral collocation solution for MHD laminar natural convection flow from a vertical permeable flat plate with uniform surface temperature and thermal radiation. Int. J. Comput Methods. 3, 850–866 (2018)

Ahamed, S.M.S., Mondal, S., Sibanda, P.: Thermo-diffusion effects on unsteady mixed convection in a magneto-nanofluid flow along an inclined cylinder with a heat source, Ohmic and viscous dissipation. J Comput Theoretical Nanosci. 13, 1670–1684 (2016)

Mondal, S, Haroun, N.A.H, Sibanda, P: The effects of thermal radiation on an unsteady MHD axisymmetric stagnation- point flow over a shrinking sheet in presence of temperature dependent thermal conductivity with Navier slip, Plos One, 10(9): e0138355 (2015) https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.%20pone.0138355

Oyelakin, I.S., Mondal, S., Sibanda, P., Mosta, S.S.: A multi-domain bivariate approach for mixed convection in a Casson nanofluid with heat generation. Walailak J Sci Tech. 16(9), 681–699 (2018)

Lai, F.C., Kulacki, F.A.: The effect of variable viscosity on convective heat transfer along a vertical surface in a saturated porous medium. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 33(5), 1028–1031 (1990)

Elbashbeshya, E.M.A., Bazidb, M.A.A.: The effect of temperature-dependent viscosity on heat transfer over a continuous moving surface with variable internal heat generation. Appl. Math. Comput. 153(3), 721–731 (2004)

Soundalgekar, V.M., Takhar, H.S., Das, U.N., Deka, R.K., Sarmah, A.: Effect of variable viscosity on boundary layer flow along a continuously moving plate with variable surface temperature. Heat Mass Transf. 40, 421–424 (2004)

Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Zheng, L.: Numerical study of thermal boundary layer on a continuous moving surface in power-law fluids. J. Therm. Sci. 16(3), 243–247 (2007)

Mahmoud, M.A.A.: Slip velocity effect on a non-Newtonian power-law fluid over a moving permeable surface with heat generation. Math. Comput. Model. 54(5-6), 1228–1237 (2011)

Kannan, T., Moorthy, M.B.K.: Effects of variable viscosity on power-law fluids over a permeable moving surface with slip velocity in the presence of heat generation and suction. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 9(6), 2791–2801 (2016)

Oyelakin, IS, Mondal, S, Sibanda, P: A multi-domain spectral method for non-Darcian mixed convection flow in a power-law fluid with viscous dissipation. Phys. Chem. Liquids: An Int. J. (2017). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00319104.2017.1399265

Othman, M.I.A., Sweilam, N.H.: Electrohydrodynamic instability in a horizontal viscoelastic fluid layer in the presence of internal heat generation. Can. J. Phys. 80(6), 697–705 (2002)

Davis, JH: Introduction to Maple. In: Differential Equations with Maple. Birkhäuser, Boston (2001)

Dinesh, P.A., Nalinakshi, N., Chandrashekhar, D.V.: Effects of internal heat generation and variable fluid properties on mixed convection past a vertical heated plate. Fluid Dynam. Mat. Proc. 10(4), 465–490 (2014)

Olver, J.: Application of Lie groups to differential equations. Springer, New York (1989)

Loganathan, O.P., Arasu, P.P.: Lie group analysis for the effects of variable fluid viscosity and thermal radiation on free convective heat and mass transfer with variable stream condition. Engineering. 2, 625–634 (2010)

Abdel-Rahman, G.M., Alessa, N.A.: Lie group for MHD and reaction porosity effects of variable viscosity on heat generation and mass transfer fluid. J. Generalized Lie Theory Applic. 12(1), 1000287 (2018)

Khalil Ur Rehman: Magnetized and non-magnetized two layer liquids: Lie symmetry analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 292 (2019). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111393

Shamshuddin, M.D., Mishra, S.R., Anwar Beg, O., Kadir, A.: Lie symmetry analysis and numerical solutions for thermo-solutal chemically reacting radiative micropolar flow from an inclined porous plate. Heat Transf. Asian Reas. 47(5), 918–940 (2018)

Schlichting, H.: Boundary layer theory. McGraw-Hill, New York (1968)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the comments of reviewers which have served to improve the present article.

Funding

We are declaring that no funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF carried out the formal analysis, investigation, and computalization and drafted the manuscript. MGM carried out the Lie group analysis and methodology. MDS participated in the investigation, visualization, review, and editing. ES participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. FG conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferdows, M., Murtaza, M.G. & Shamshuddin, M. Effect of internal heat generation on free convective power-law variable temperature past a vertical plate considering exponential variable viscosity and thermal conductivity. J Egypt Math Soc 27, 56 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-019-0062-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-019-0062-5