Abstract

Background

Entomopathogenic fungi are widely distributed and well described within the fungal kingdom. This study reports the isolation, characterization, and virulence of 4 Purpureocillium lilacinum isolates against the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae).

Results

Four strains of Purpureocillium lilacinum (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27) were isolated from soil samples from different localities of China. The morphological studies observed that four strains showed essentially the same morphological characteristics. After 7 days of cultivation, the colonies were purple, round, and bulged. Conidia were single-celled, oval to spindle-shaped, chain-like, and the spore size was about 2.0–2.3 × 3.1–4.0 μm. The genome-based identification results showed that ITS sequences of XI-1 (GenBank accession # MW386433), XI-4 (GenBank accession # MW386434), XI-5 (GenBank accession # MW386435), and J27 (GenBank accession # MW386436) were similar to another P. lilacinum. The newly identified strains of P. lilacinum proved pathogenicity to B. tabaci under laboratory conditions. In addition, the P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 was the most virulent one against different nymphal instars of whitefly having median lethal concentration (LC50) values of 4.99 × 106, 4.82 × 105, and 2.85 × 106 conidia/ml, respectively, 7 days post application.

Conclusion

The newly isolated strains of P. lilacinum can be developed as a potential biopesticide against the whitefly although extensive field bioassays as well as development of proper formulation are still required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), is a key pest of different crops and vegetables worldwide along with serving as a vector of many plant viruses (Naranjo et al. 2010 and Stansly and Naranjo, 2010). B. tabaci Middle East-Asia Minor 1 (MEAM1) cryptic species (formerly “B biotype”) exists in 31 provinces or municipalities of the People’s Republic of China causing huge economic losses to different crops (Liu and Liu 2012). Management of heavy whitefly infestations is still mainly dependent upon broad spectrum conventional insecticides, which have led to the development of insecticide resistance by B. tabaci (Liang et al. 2012). Therefore, finding alternate pest control strategies such as use of entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) is necessary in order to overcome the abovementioned problems (Cuthbertson et al. 2005).

Identification and characterization of EPF is an initial step of biopesticide development (Dunlap et al. 2017). During the past decade, the techniques employed for isolation and identification of EPF have evolved from morphological characterization to amplification of different DNA or RNA fragments through polymerase chain reactions improving the basic understanding about EPF (Canfora et al. 2016). In recent years, molecular techniques have become widely used for identification of EPF as the genotypic identification methods (such as random amplified polymorphic DNA-polymerase chain reaction) are more precise than the morphological character-based identification (Du et al. 2019).

The genus Purpureocillium Luangsa-ard (Hypocreales: Ophiocordycipitaceae), previously classified in genus Paecilomyces, consists of fungal species having pathogenicity against herbivore insects and different species of nematodes (Fan et al. 2013; Goffré and Folgarait, 2015). P. lilacinum is a known species being used for biological control of aphids, thrips, whiteflies, fruit flies, beetles, mosquitoes, and plant parasitic nematodes (Amala et al. 2013; Goffré and Folgarait 2015). P. lilacinum isolates are sometimes misidentified to Isaria spp. as the anamorphs of both groups are similar (Yamamoto et al. 2020). Therefore, use of genotypic identification tools should prove an effective solution for the correct identification.

The present experiments reported morphological and genome-based identifications of 4 P. lilacinum isolated from soil samples collected from different localities of China along with their virulence against B. tabaci under laboratory conditions.

Methods

Insect culture

Whitefly cultures, reared (Gossypium hirsutum on 26 ± 1 °C, 70 ± 10% R.H. and 14:10 h light: dark photoperiod) at the Engineering Research Center of Biological Control, Ministry of Education, South China Agricultural University, were used during this study.

Collection of soil samples and isolation of fungi

Samples of soil for fungal isolation were collected from different provinces of the People’s Republic of China during 2015–2017. The samples were collected from 10 cm below the soil surface and placed in plastic bags. Collected samples were stored at 4 °C. Fungi were isolated by the methods of Imoulan et al. (2011) and Du et al. (2019). Briefly, a mixture of soil sample (3 g) and 30 ml sterilized 0.05% Tween-80 solution in ddH2O was prepared by stirring for 15 min. The prepared suspension (1 ml) was inoculated on PDA plates, followed by incubation at 25 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% R.H, 16:8 h (light/dark photoperiod). The PDA plates were observed after 7 days of inoculation, followed by re-inoculation of grown fungi to fresh PDA plates. The inoculation process was repeated until pure fungal culture was obtained. According to the phenotypic characteristics and fungal morphology (Saito and Brownbridge 2016), the cultured fungi were purified until there was only one fungus colony on the PDA plate.

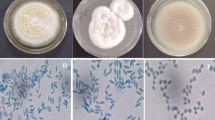

Morphological characterization

Morphological characters of 4 fungal isolates (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27) were studied through inoculating fungal mycelial plug (1 cm Ø) observed by culturing small fungal mycelia PDA block draped by a cover slip for 10 days (Imoulan et al. 2011; Du et al. 2019). The slides were stained by lactophenol cotton blue and were observed under a phase-contact microscope (×100). Conidial images were taken through Axio Cam HRc camera (Carl Zeiss) having the AxionVision SE64 Release 4.9.1 software.

Fungal growth and conidia production

Expansion rates of fungal colonies and conidia production by different P. lilacinum isolates were observed, following Ali et al. (2009). Fungal mycelial plugs (1 cm Ø) were cultured on PDA plates, followed by incubation at 25 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% R.H and 16:8 h (light/dark photoperiod) for 10 days. Colony growth was measured every day, and conidia were scrapped from PDA plates 10 days post inoculation. Conidia were added into 100 ml of 0.05% Tween-80. Muslin cloth was used to filter the conidial suspension. Total conidial yield was calculated by counting the conidia in a hemocytometer under a phase-contrast microscope at × 40 (Ali et al. 2009).

Observation of spores of strains by scanning electron microscopy

Conidia were harvested from a PDA plate, and the conidial suspensions at the 1 × 107 conidia/ml were prepared by using deionized water containing 0.05% Tween-80 solution. Conidial suspensions (8 ml) were inoculated into 100 ml SDA medium (1% peptone, 4% glucose), and the inoculated medium was cultured at 26 °C, 180 rpm for 5 days. The hyphae were obtained through a vacuum suction pump and were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 24 h, rinsed with phosphate buffer solution, dehydrated, and dried with alcohol, and the sample was fixed on the sample stage with a conductive adhesive and photographed with a scanning electron microscope (SU8020, Hitachi, Japan).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequence analysis

Genomic DNA of newly isolated fungi was obtained by using a fungal DNA isolation kit (Ezup, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The obtained DNA served as a template for amplification of ITS (internal transcribed spacer) fragment through PCR. Reaction mixture (50 μl) was used to perform all PCR reactions. The ITS primers (ITS4F: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC; and ITS5R: GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG) reported by White et al. (1990) were used to amplify ITS regions. The PCR cycling and conditions of Du et al. (2019) were used for amplification of ITS regions. The purity of PCR products was observed through agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by GenGreen (TianGen Biotech, Beijing, China) staining. Pure PCR products were sequenced by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology (Shanghai, China). Geneious version 9.1.4 was used to assemble the sequences, followed by GenBank blast. MEGA version 7.0 was used to compare the sequences whereas Kimura-2-parameter (K2P) was used to build maximum likelihood (ML) tree (Kimura, 1980; Goloboff and Catalano, 2016).

Insect bioassays

Pathogenicity of isolated fungi against B. tabaci

The newly isolated P. lilacinum strains (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27) grown on PDA were used to prepare conidial suspension (1 × 108 conidia/ml), following Ali et al. (2009). The leaf dip bioassay method of Zhang et al. (2017) was used to carry out the pathogenicity studies. Cotton leaves having 2nd instar B. tabaci nymphs were dipped in the fungal suspension for 30 s. The leaves were air dried and placed in ø 9 cm having a moist filter paper for moisture maintenance. B. tabaci nymphs, dipped in 0.01% Tween 80, served as control. Four cotton leaves having 100 B. tabaci nymphs/leaf were used in each treatment. The whole experimental setup was placed at 25 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% R.H and 16:8 h (light/dark photoperiod). The whole experiment was performed thrice (with fresh batch of insects and fresh conidial suspension). Insect mortality was recorded on daily basis until 7 days post treatment.

Pathogenicity of P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 against immature instars of B. tabaci

Different conidial concentrations (1 × 108, 1 × 107, 1 × 106, 1 × 105, and 1 × 104 conidia/ml) of P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 were prepared following Ali et al. (2009). Cotton leaves having B. tabaci nymphs (2nd, 3rd, or 4th instars) were dipped in each conidial concentration for 30 s. The leaves were air dried and placed in ø 9 cm having a moist filter paper for moisture maintenance. B. tabaci nymphs, dipped in 0.01% Tween 80, served as control. Four cotton leaves having 100 B. tabaci nymphs/leaf were used in each treatment. The whole experimental setup was placed at 25 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% R.H and 16:8 h (light/dark photoperiod). The whole experiment was performed thrice (with fresh batch of insects and fresh conidial suspension). Insect mortality was recorded on daily basis until 7 days post-treatment.

Transmission electron microscopy

Second instar B. tabaci nymphs treated with P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 (1.0 × 108 conidia/ml) were observed for external as well as internal anatomical changes after different 3, 5, and 7 days post-treatment. The insects’ samples were treated and observed following Du et al. (2019).

Statistical analysis

Data regarding colony expansion rate and conidial yield were analyzed through ANOVA-1, and significant differences among means were calculated through Tukey’s HSD test (P ≤ 0.05). Insect mortality values were percent-transformed, followed by probit analysis (Finney et al. 1971). The SAS 9.2 software was used for all data analysis (SAS et al. 2000).

Results

Morphological identification of fungal isolates

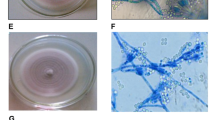

The four strains showed essentially the same morphological characteristics. The morphological characteristic is reported below. First, it grows white colonies, such as the edges of the colonies were white. The later growth gradually turned purple. After 7 days of cultivation, the colonies were purple, round, and bulged. The texture was tightly cotton-like, and there was no secretion on the surface (Fig. 1). Conidia are single-celled, oval to spindle-shaped, chain-like, and the spore size is about 2.0–2.3 × 3.1–4.0 μm microns (Fig. 2). The radial growth/day of fungal isolates showed significant differences after 7 days of growth (F3,16 = 36.77, P < 0.001). The highest colony expansion rate (3.67 mm/day) was observed for P. lilacinum isolate J27, whereas the lowest minimum colony expansion rate was recorded for P. lilacinum isolate XI-4, having a mean value of 3.09 mm/day (Table 1).

Colony morphology of different Purpureocillium lilacinum isolates after 7 days of growth. a Frontal view of isolate XI-1 colony. b Rear view of isolate XI-1 colony. c Frontal view of isolate XI-4 colony. d Rear view of isolate XI-4 colony XI-4. e Frontal view of isolate XI-5 colony. f Rear view of isolate XI-5 colony XI-5. g Frontal view of isolate J-27 colony. h Rear view of isolate J-27 colony

Means followed by lowercase letters in the same columns are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s P ≤ 0.05); ± indicate the standard error of means based on five replicates (n = 5)

The number of conidia produced by different fungal isolates showed significant differences after 7 days of growth (F3,16 = 271.26, P < 0.001). The highest conidial yield (3.78 × 106 conidia/ml) was observed for P. lilacinum isolate XI-1, whereas the lowest conidial yield was obtained from P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 having a mean value of 8.8 × 105conidia/ml (Table 1). The conidial polymorphism found within these isolates is probably due to their genetic variability (Varela and Morales, 1996).

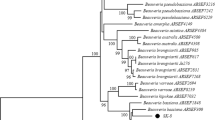

Molecular analyses and BLASTN comparisons

Partial ITS sequences were obtained through PCR amplification of purified DNA. The sequence length of ITS fragment of XI-1 was 535 bp, XI-4 was 543 bp, XI-5 was 536 bp, and J27 was 540 bp. The results showed that ITS sequence of XI-1 (GenBank accession # MW386433) was 99.81% similar to another P. lilacinum GenBank sequence FJ765024.1. The ITS XI-4 sequence (GenBank accession # MW386434) showed 99.45% similarity with P. lilacinum sequences HQ607867.1, while ITS sequence of XI-5 (GenBank accession # MW386435) was 99.81% similar to P. lilacinum sequence GU980033.1. The ITS sequence of P. lilacinum isolate J27 (GenBank accession # MW386436) was 100% similar to P. lilacinum strain sequences MK361144.1. The details of GenBank sequences used are shown in Table 2. Multiple comparisons were performed by Clustal W, and phylogenetic trees were constructed separately according to the maximum likelihood method, and B. bassiana was used as an outgroup. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

Pathogenicity of P. lilacinum against B. tabaci

Preliminary bioassays of different fungal isolates against B. tabaci

The mortalities of B. tabaci nymphs, following treatment with P. lilacinum isolates (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27), were significantly different at the end of experimental period. The highest corrected B. tabaci mortality (86.81%) was caused by P. lilacinum isolate XI-5. P. lilacinum isolate XI-1 proved the least virulent having corrected mortality value of 46.24% (Fig. 4). The median lethal concentration (LC50) values after 7 days of application were significantly different among different isolates. The highest LC50 value (3.44 × 108 conidia/ml) was observed at P. lilacinum isolate XI-1, while the lowest LC50 value (4.82 × 105 conidia/ml) was observed at P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 (Table 3).

Means followed by lowercase letters in the same columns are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s P ≤ 0.05)

The median lethal time (LT50) values of different P. lilacinum isolates against B. tabaci, when applied at a rate of 1 × 108 conidia/ml, showed significant differences. The highest LT50 value (7.13 days) was observed for P. lilacinum isolate XI-1, while the lowest LT50 value (2.54 days) was observed for P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 (Table 4).

Means followed by lowercase letters in the same columns are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s P ≤ 0.05)

Concentration mortality response of P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 against different nymphal instars of B. tabaci

Mortality rates of B. tabaci nymphs (1st, 2nd, and 3rd instars), following treatment with P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 increased with increase of fungal concentrations (Fig. 5). LC50 of P. lilacinum isolates XI-5 against different nymphal instars of B. tabaci were obtained through probit analysis. The LC50 of P. lilacinum isolates XI-5 were 4.99 × 106, 4.82 × 105, and 2.85 × 106 conidia/ml against 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instar nymphs, respectively (Table 5).

Means followed by lowercase letters in the same columns are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s P ≤ 0.05)

Microscopic examination of B. tabaci infection

B. tabaci nymphs infected with P. lilacinum XI-5 showed significant morphological changes at different infection periods. The physical appearance of B. tabaci did not change much after 1 day of fungal application. On the 3rd day of infection, the fungal hyphae started to grow from the edges of the insect’s body. On the 5th day of post-fungal application, the hypha covered most of the insect’s body and turned yellowish brown. On the 7th day was post-fungal application, the insects were covered with hyphae (Fig. 6). Transmission electron microscope images clearly showed that the hyphae proliferated massively and occupied the whole haemocoel at 72 h post-inoculation (Fig. 7). Obtained findings revealed that B. tabaci were penetrated and killed by P. lilacinum XI-5 (Fig. 7).

Discussion

The correct understanding of taxonomy/identification as well as pathogenic potential of microbial control agents is a pre-requisite for their development as an alternative to synthetic chemicals (Du et al. 2019). During this study, 4 fungal isolates of P. lilacinum were identified on phenotypic as well as their genotypic basis. All of the identified isolates tested for their pathogenicity against 2nd instar B. tabaci nymphs showed considerable pathogenic potential. The concentration response relationship studies confirmed the pathogenic ability of P. lilacinum isolate X1-5 against different immature life stages of B. tabaci.

Hypocrealean fungi, being a large and complex group, are not easy to classify based on morphological characters, which has led to the use of genomic data for identification of these fungi (Lu et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2017). The ITS rDNA fragment is a commonly used gene to classify morphologically similar species of fungi (Lu et al. 2015). The pairwise comparison of ITS sequence data showed that strains XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27 had 99–100% similarity with different previously described strains of P. lilacinum (GenBank # FJ765024.1, HQ607867.1, GU980033.1, and MK361144.1).

The present studies revealed pathogenic capacities of the 4 P. lilacinum isolates (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27) against B. tabaci. Intraspecific variation was observed within different isolates during pathogenicity studies. The calculation of LT50 for different isolates revealed that isolate XI-5 seemed to be the most virulent one, when compared to other isolates, which is in line with the idea of pathogenicity as the ability of a pathogen to induce disease in target host described by Steinhaus and Martignoni (1970). The highest pathogenicity of P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 compared to other isolates can be attributed to variation in production of infection-related proteins or toxins (Khan et al. 2004). The variations might be related to different target insect species or size of the insect host (Jandricic et al. 2014). Based on these preliminary findings, P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 can be used for development of biopesticides against B. tabaci.

Conclusions

The newly identified strains of P. lilacinum (XI-1, XI-4, XI-5, and J27) showed good growth characteristics and caused considerable mortality to B. tabaci nymphs. P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 was the most virulent one. Based on these preliminary findings, P. lilacinum isolate XI-5 could be suggested for development of a biopesticide against B. tabaci.

Availability of data and materials

The data and material used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PDA:

-

Potato dextrose agar

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- LC50 :

-

Median lethal concentration

- LT50 :

-

Median lethal time

References

Ali S, Huang Z, Ren S (2009) Media composition influences on growth, enzyme activity, and virulence of the entomopathogen hyphomycete Isaria fumosoroseus. Entomol Exp et Appl 131:30–38

Amala U, Jiji T, Naseema A (2013) Laboratory evaluation of local isolate of entomopathogenic fungus, Paecilomyces lilacinus Thom Samson (ITCC 6064) against adults of melon fruit fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae Coquillett (Diptera; Tephritidae). J Trop Agric 51:132–134

Canfora L, Malusà TCM, Tartanus E, Łabanowska BH, Pinzari F (2016) Development of a method for detection and quantification of B. brongniartii and B. bassiana in soil. Sci Rep 6: 22933.

Cuthbertson AGS, Walters KFA, Northing P (2005) Susceptibility of Bemisia tabaci immature stages to the entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium muscarium on tomato and verbena foliage. Mycopathol 159:23–29

Du CL, Yang B, Wu JH, Ali S (2019) Identification and virulence characterization of two Akanthomyces attenuatus isolates against Megalurothrips usitatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Insects 10(6):168

Dunlap CA, Ramirez JL, Mascarin GM, Labeda DP (2017) Entomopathogen ID: a curated sequence resource for entomopathogenic fungi. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 111:897–904

Fan YM, Tong XL, Gao LI, Wang M, Liu ZQ, Zhang Y, Yang Y (2013) The spatial aggregation pattern of dominant species of thrips on cowpea in Hainan. J Environ Entomol 35:737–743

Finney JG, Smith DF, Skeeters DE, Auvenshine CD (1971) MMPI alcoholism scales: factor structure and content analysis. J Stud Alcohol 32:1055–1060

Goffré D, Folgarait PJ (2015) Purpureocillium lilacinum, potential agent for biological control of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex lundii. J Invertebr Pathol 130:107–115

Goloboff PA, Catalano SA (2016) TNT version 1.5, including a full implementation of phylogenetic morphometrics. Cladisitics 32:221–238

Imoulan A, Alaoui A, Meziane AE (2011) Natural occurrence of soil-borne entomopathogenic fungi in the Moroccan Endemic forest of Argania spinosa and their pathogenicity to Ceratitis capitata. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 27:2619–2628

Jandricic SE, Filotas M, Sanderson JP, Wraight SP (2014) Pathogenicity of conidia-based preparations of entomopathogenic fungi against the greenhouse pest aphids Myzus persicae, Aphis gossypii, and Aulacorthum solani (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J Invertebr Pathol 118:34–46

Khan A, Williams K, Nevalainen H (2004) Effects of Paecilomyces lilacinus protease and chitinase on the eggshell structures and hatching of Meloidogyne javanica juveniles. Biol Control 31:346–352

Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120

Liang P, Tian YA, Biondi A, Desneux N, Gao XW (2012) Short-term and trans-generational effects of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on susceptibility to insecticides in two whitefly species. Ecotoxicol 21:1889–1898

Liu YQ, Liu SS (2012) Species status of Bemisia tabaci complex and their distributions in China. J Biosaf 21:247–255

Lu L, Cheng B, Du D, Hu X, Peng A, Pu Z, Zhang X, Huang Z, Chen G (2015) Morphological, molecular and virulence characterization of three Lecanicillium species infecting Asian citrus psyllids in Huangyuan citrus groves. J Invertebr Pathol 125:45–55

Naranjo SE, Castle SJ, De Barro PJ, Liu SS (2010) Population dynamics, demography, dispersal and spread of Bemisia tabaci. Bemisia: Bionomics and Management of a Global Pest. Stansly PA, Naranjo S (eds) Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 185-226.

Saito T, Brownbridge M (2016) Compatibility of soil-dwelling predators and microbial agents and their efficacy in controlling soil-dwelling stages of western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis. Biol Control 92:92–100

SAS TCJ, Gerver WJM, Bruin RD, Mulder PGH, Cole TJ, Wall WD, Hokken-Koelega ACS (2000) Body proportions during 6 years of GH treatment in children with short born small for gestational age participating in a randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial. Clin Endocrinol 53:675–681

Stansly PA, Naranjo SE (2010) Bemisia: bionomics and management of a global pest. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Steinhaus EA, Martignoni ME (1970) An abridged glossary of terms used in invertebrate pathology, 2nd edn. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, Corvallis, Oregon, USA

Varela A, Morales E (1996) Characterization of some Beauveria bassiana isolates and their virulence toward the coffee berry borer Hypothenemus hampei. J Invertebr Pathol 67:147–152

Wang DK, Deng JX, Pei YF, Li T, Jin ZY, Liang L, Wang WK, Li LD, Dong XL (2017) Identification and virulence characterization of entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium attenuatus against the pea aphid Acyrthos iphonpisum (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Appl Entomol Zool 52:511–518

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: Genes for Phylogenetics. Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, pp 315–322.

Yamamoto K, Yasuda M, Ohmae M, Sato H, Orihara T (2020) Isaria macroscyticola, a rare entomopathogenic species on Cydnidae (Hemiptera), is a synnematous form and synonym of Purpureocillium lilacinum (Ophiocordycipitaceae). Mycoscience 61:160–164

Zhang C, Ali S, Musa PD, Wang XM, Qiu BL (2017) Evaluation of the pathogenicity of Aschersonia aleyrodis on Bemisia tabaci in the laboratory and greenhouse. Biocontrol Sci Tech 27:210–221

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the handling editor and anonymous reviewers for kind suggestions and comments.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2018B020206001) and Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, P.R. China (201807010019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. designed the study. T.S. and J.H.W performed the experiment and took pictures. T.S. and J.H.W did data curation and investigation. S.A. analyzed data and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

I agree to all concerned regulations.

Consent for publication

I agree to publish this scientific paper in the EJBPC.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, T., Wu, J. & Ali, S. Morphological and molecular identification of four Purpureocillium isolates and evaluating their efficacy against the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Egypt J Biol Pest Control 31, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00372-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00372-y