Abstract

Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid is a destructive pathogen of cowpea that causes serious charcoal rot disease with significant yield losses. Antifungal activity of three indigenous Ascomycetes viz., Trichoderma harzianum, T. viride, and T. hamatum, and two Meliaceae members, i.e., Melia azedarach L. and Azadirachta indica L. were assessed against the pathogen. Laboratory screening trials with cell-free culture filtrate showed the maximum reduction in growth of M. phaseolina with T. harzianum, followed by T. viride. Various concentrations (1–5%) of methanolic leaf extract of A. indica showed more reduction in fungal biomass than M. azedarach. Pot experiment was performed by T. harzianum, T. viride, and dry leaf biomass of A. indica against M. phaseolina. Results revealed that potted soil amended with T. harzianum in combination with 1–3% dry leaf biomass of A. indica held a significant potential to decrease disease incidence to 20–25% and improve plant growth attributes up to fourfolds over positive control inoculated with M. phaseolina only. Physiology of the host plant was altered due to the incorporation of various soil amendments resulting in reduced activities of antioxidant enzymes (catalase, peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, and phenylalanine ammonia lyase). It was concluded that fungal antagonists and allelopathic chemicals would be an effective and eco-friendly means of managing the charcoal rot disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) is one of the most important, oldest, herbaceous legume crop, widely cultivated for fodder and grain in the Pakistan and semi-arid tropics of the world (Mensack et al. 2010). Its substantial adaptation to drought, elevated temperatures, a wider spectrum of pH, requirement of less fertilizers and minimal irrigation relative to many other legumes, increase its preference by the farmers in improving their socio-economic status and in contributing agricultural productivity. However, cowpea growth and productivity are suppressed by very destructive and economically important charcoal rot disease caused by the seed and soil-borne necrotrophic fungus Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid. The pathogen is widely distributed in the regions with high temperatures and drought conditions, while it is responsible for infecting more than 500 plant species including cowpea, mung bean, chickpea, sorghum, sunflower, etc. Disease causes wilting of host plant after infection and pathogen keeps on producing microsclerotia in senescing shoot tissues which causes further decay of host tissue (Mayek-Perez et al. 2001).

There are no effective fungicides or other control methods to limit M. phaseolina (Gaige et al. 2010). Disease management through utilizing native antagonistic soil fungi and allelopathic plants is an attractive alternative among the disease management practices. Trichoderma is a common filamentous biocontrol fungal agent, found almost in any soil type. The antifungal activity of this genus is associated with improvement in growth and systemic resistance in plant (Harman et al. 2006). Several antagonistic mechanisms like nutrient competition, antibiotic production, and mycoparasitism generally work in Trichoderma against the pathogen (Vinale et al. 2008). Many biocontrol mycoparasitic species of Trichoderma have been well studied including T. harzianum, T. viride, T. hamatum, T. koningii, and T. reesei against M. phaseolina (Khalili et al. 2012), and many have been developed into a commercial biocontrol product.

Utilization of plant extract and biomass is another environment friendly way of managing the disease as a source of natural pesticides. Plants are store house of biochemicals that contribute in suppressing phytopathogens (Sales et al. 2016). These biochemicals (nitrogen-containing compounds and phenolics) function as a defense and chemical signal molecule against pathogens. Previous literature showed that phytochemicals of Melia azedarach and Azadirachta indica, besides holding medicinal values, have shown considerable fungicidal activity against pathogenic fungi including M. phaseolina (Carpinella et al. 2003). The present study was planned to investigate antifungal activity of three indigenous Ascomycetes fungal species viz., T. harzianum, T. viride, and T. hamatum, and two Meliaceae members, i.e., M. azedarach and A. indica against M. phaseolina responsible for charcoal rot disease in cowpea through in vitro trials.

Materials and methods

Laboratory bioassays

Three Trichoderma species, i.e., T. viride (FCBP 644), T. harzianum (FCBP 1277), and T. hamatum (FCBP 907), were tested for their antagonism activity against M. phaseolina (FCBP 0751).

Antifungal activity of Trichoderma spp. by cell-free culture filtrates

Cell-free culture filtrates Trichoderma spp. were prepared in 2% ME (malt extract) broth medium (100 mL). After 20 days of inoculation, cell-free supernatants were collected after aseptic filtration through Whatman filter paper and centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min, followed by re-filtration through Millipore filter paper (pore size 45 μm). Twenty-one different concentrations, ranging from 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70,…, 100% (v/v) of each cell-free culture filtrate, were prepared by addition of 2% of ME. Flasks were inoculated with 5 mm disc of M. phaseolina and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C. After 7 days, mycelial mat was dried in oven at 45 °C for 24 h for measuring dry biomass.

Assessment of the antifungal potential of plant extract

Two hundred-gram powdered leaves of A. indica and M. azedarach were soaked in 2 L methanol separately for 12 days. Extracts were obtained from soaking materials by filtering and evaporating and finally drying. Original concentration was made by dissolving 9 g of extracting plant material in 5 ml of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO 99.5%) to prepare a final volume of 15 ml. Control solution was made by adding 5 ml of DMSO in 10 ml of sterilized distilled water. Six concentrations, i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5%, were made by adding 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 ml of stock solution and 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0 ml of control solution in 55 ml of each flask to make a final volume of medium 60 ml. Then, 60 ml of each treatment was equally divided into four 100-ml flasks to serve as replicates, where 0% was control treatment. Actively growing culture of M. phaseolina (5 mm disc) was inoculated in each flask and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 7 days. The fungal biomass was dried and weighed.

Pot bioassays

On the basis of the laboratory bioassays, two species of Trichoderma viz. T. harzianum and T. viride, and one member of Meliacaceae family, i.e., A. indica, were selected to conduct trials in pots (6 in. diameter × 10 in. height). Initially, presterilized potted soil (1 kg pot−1) was inoculated with cultural suspension (conidial count 4 × 106) of each of two Trichoderma spp. and left for 4 days for the establishment of the fungus in soil. Later dry leaves of A. indica were mixed at 1, 2, and 3% in 1 kg of soil and left for 7 days. Soil was inoculated with M. phaseolina (MP) and left for another 4 days for inoculum establishment. Finally, surface sterilized seeds of cowpea with 0.1% sodium hypochlorite solution were sown in each pot. The pots were arranged in a completely randomized design and were kept under natural environmental conditions having three replicates of each treatment. Experiment was comprised of 13 treatments including T 1 : negative control (without any inoculation or amendment); T 2 : positive control (inoculated with MP only); T 3 –T 5 : MP + 1% A. indica, MP + 2% A. indica and MP + 3% A. indica; T 6 : MP + T. harzianum; T 7 –T 9 : MP + T. harzianum + 1% A. indica, MP + T. harzianum + 2% A. indica, MP + T. harzianum + 3% A. indica; T 10 : MP + T. viride; T 11 –T 13 : MP + T. viride + 1% A. indica; MP + T. viride + 2% A. indica, and MP + T. viride + 3% A. indica.

Disease assessment

After 40 days of inoculation charcoal rot disease symptoms on cowpea plants, were appeared and were assessed, using disease rating scale, where 1: no symptoms on plants (highly resistant); 3: lesions are limited to cotyledonary tissues (resistant); 5: lesions have progressed from cotyledons to about 2 cm of stem tissues (tolerant); 7: lesions are extensive on stem and branches (susceptible); and 9: most of the stem and growing points are infected. A considerable amount of pycnidia and seclerotia are produced (highly susceptible). Disease incidence (DI) was determined, using the following formula:

Analysis of plant physiology

Physiological variations in different treatments were assessed in cowpea leaves after 40 days of seed sowing. Total chlorophyll content was quantitatively analyzed by taking absorbance properties for chlorophyll a (645 nm), chlorophyll b (663 nm), and carotenoid (270 nm), and the amount of pigment was calculated. Activity of catalase (CAT) was determined in the reaction mixture consisted enzyme extract (0.1 ml) that was added to 2.9 ml of H2O2 (20 mM) and sodium phosphate buffer (50 mol/L; pH 7.0) by monitoring the reduction in the absorbance at 240 nm (Maehly and Chance 1967). Activity of peroxidase (POX) was determined by taking 0.5 ml of enzyme extract in reaction mixture containing 2 ml of 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and 1 ml of pyrogallol. Solution was filled with 1 ml of 0.05 mol/L H2O2 (5:5 in H2O2 and distilled water), incubated at 25 °C, and reaction was stopped by adding 2.5 mol/L H2SO4 (24.5 ml of H2SO4 + 100 ml of distilled water). The amount of purpurogalline formed was determined by reading the absorbance at 430 nm against a blank prepared by adding the extract after the addition of 2.5 mol/L H2SO4 (Colville and Smirnoff 2008). Polyphenol oxidase activity (PPO) was assayed in a reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 ml enzyme extract and 1.5 ml of 0.1 mol/L sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.2 ml of 0.01 mol/L catechol. The changes in the absorbance were recorded at 30-s interval for 3 min at 495 nm (Mayer et al. 1965). For determination of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity, reaction mixture [(0.4 ml of enzyme extract + 0.1 mol/L sodium borate buffer (pH 8.8) + 0.5 ml of 0.012 mol/L l-phenylalanine)] was incubated for 1 h in light at 25 °C and reaction was stopped by incubating at 47 °C for 10 min. The amount of trans-cinnamic acid formed was calculated after measuring absorbance of samples at 290 nm (Dickerson et al. 1984).

Harvesting and data collection

Plants were harvested after 65 days of sowing. Data regarding disease incidence, and plant height, shoot, root fresh, and dry weight were measured. Materials were dried at 70 °C, and dry weight was recorded on an electric balance.

Statistical analysis

Triplicate values reported are mean of ±SD. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (normality test) and Levene’s test (variance test) were applied before any statistical analysis. When all the assumptions of ANOVA were satisfied, standard errors of all data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by LSD test, using computer software Statistix 8.1.

Results and discussion

Laboratory trials

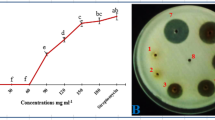

Increasing concentrations (5–100%) of cell-free culture filtrate of the three Trichoderma spp. were found highly effective in suppressing growth of M. phaseolina. Thus, the highest inhibition of 10–90% in the biomass of M. phaseolina was recorded due to cell-free culture filtrate (CFC) of T. harzianum, followed by 5–70% due to CFC of both T. viride and T. hamatum as compared to control (Table 1). Likewise, Naglot et al. (2015) and Khaledi and Taheri (2016) reported inhibition in growth of M. phaseolina by different Trichoderma spp, whereas the difference in concentration of volatile substances (acetaldehyde, isocyanide derivatives, terpene, hydrazine, alcohols, lactones, etc.) and cell wall degrading enzymes (chitinase and glucanase) might be ascribed to dissimilar fungicidal activity of three Trichoderma spp. (Woo et al. 2006). Considering the significant antifungal activity of T. harzianum and T. viride against M. phaseolina, the two species were later used in the pot study.

In laboratory trials, different concentrations (1–5%) of leaf extract of M. azedarach and A. indica significantly reduced M. phaseolina growth by 19–61 and 25–72%, respectively (Table 2). Reduction in fungal biomass to increase in the concentration of plant extract has been reported by several authors (Latha et al. 2009). Many chemicals and biological active compounds have been identified in the leaf extract of A. indica (phytol, octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester, hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester, etc.) (Hossain et al. 2013) and in M. azedarach (β-sitosterol, β-amyrin, ursolic acid, benzoic acid, and 3-5 dimethoxy benzoic acid) (Jabeen et al. 2011). The significant reduction in growth of the fungus treated with two plant species was probably due to a difference in occurrence of inhibitors to the fungitoxic principle (Baka 2010).

Pot trials

Effect on disease and growth

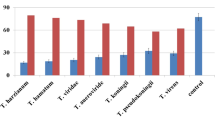

There was no disease in negative control. The highest disease incidence of 75% was recorded in positive control, where only M. phaseolina was inoculated in the soil. Soil amendments with 1–3% dry leaf biomass of A. indica significantly reduced the disease incidence from 50 to 30% over positive control. MP + T. harzianum or MP + T. viride significantly reduced disease incidence to 23 and 39%, respectively. The combined effect of antagonistic fungi with soil amendment was more pronounced. Therefore, T. harzianum with 1–3% dry biomass of leaf showed the highest reduction in disease incidence from 20 to 8% (Table 3).

Soil inoculation with M. phaseolina significantly decreased length and biomass by 48 and 63%, respectively, with respect to the negative control. There was ~ 55, 100, and 150% increase in said growth attributes of cowpea due to soil amendment with leaf biomass (1–3%). In MP + T. harzianum, length and dry biomass were significantly improved by 159 and 227%, respectively, in combination with leaf biomass of A. indica (1–3%) by 200 and 450% over positive control. When T. viride was provided alone or combined with 1–3% leaf biomass of A. indica, the studied parameter was considerably enhanced by 117–255% over positive control (Table 3).

Highest disease incidence and the maximum reduction in cowpea plant growth attributes due to M. phaseolina inoculation might be ascribed to effect of fungal toxins that could hinder uptake of important minerals in plants, thus disturb the normal functioning of plant possibly by increasing respiration rate, membrane degradation, abnormal stomatal behavior, and abrupt transpiration with excessive loss of water (Heiser et al. 1998).

All biofungicides effectively managed disease by improving growth and physiological attributes in cowpea plants. Soil incorporation with T. harzianum proved more effective as compared to T. viride and dry leaf biomass of A. indica. In either case, combined application of Trichoderma spp. with leaf biomass showed a better effect on cowpea as compared to either biofungicides given alone. However, T. harzianum in combination with dry leaf biomass of A. indica showed the maximum disease management and improvement in plant growth. Lower level of disease incidence and improvement in plant growth attributes after incorporation of soil amendments could be due to their antifungal action that could be further ascribed to enhancement in host resistance, induction of a hypersensitive response through inhibiting growth of M. phaseolina, and conservation of root system function (Vinale et al. 2008). As the Trichoderma species exhibit the ability to grow fast and produce large spore that would be another factor behind the disease suppression as Trichoderma can uptake nutrients more efficiently as compared to a pathogen (Vinale et al. 2008). Besides improvement in soil texture, soil physicochemical properties with better aeration may provide a more suitable environment for the beneficial microbes as compared to the pathogen. The net results of soil amendments seemed to improve plant physiology ultimately resulting in better plant health. Likewise, allelochemicals effect induced by leaves biomass of A. indica might have antagonist effect on the pathogen. Under combined effect of T. harzianum and leaves biomass of A. indica, it appears that disease causing ability of the pathogen have been shifted towards its survival under stress conditions imposed by fungicidal action of allelochemicals and competition for resources between the pathogen and antagonistic fungi.

Effect on plant physiology

Effect on total chlorophyll content

Total chlorophyll content was significantly declined by 60% over negative control due effect of pathogen. Application of different doses of dry leaf manure (1–3%) significantly increased the said attribute up to 165–195% over positive control. In MP + T. harzianum, this parameter was improved by 230% and more profoundly by 265–320% in MP + T. harzianum + A. indica (1–3%). Effect of MP + T. viride and MP + T. viride + A. indica (1–3%) was also significant in improving total chlorophyll content by 200 and 220–255%, respectively, over positive control (Table 4). Damage to thylakoid membrane, reduction of the ribulose 1-5 biphosphate regeneration and overall disturbance in plant photosynthesis network (Petit et al. 2006) could be a cause of decline in total chlorophyll content of cowpea leaves after pathogen infection. Fungicidal action of leaf biomass of plant and Trichoderma spp. enhanced plant physiology that may direct synthesis of chloroplast enzymes due to which rubisco activity was enhanced (Khodary 2004) resulted in an increase of the total chlorophyll content.

Effect on enzyme activities

CAT, POX, PPO, and PAL activities were significantly enhanced ~ two-folds due to effect of M. phaseolina over negative control and incorporation of various biofungicides significantly reduced it over positive control. The highest reduction of 30–50% in enzymes activities were recorded in MP + T. harzianum and in combination with leaves dry biomass over positive control. Likewise, MP + A. indica (1–3%) and MP + T. viride or MP + T. viride + A. indica (1–3%) showed significant reductions of 20–30% in enzymes activities over positive control (Table 4). Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide during so-called “oxidative burst,” are the earliest responses, following successful pathogen recognition. ROS may be directly involved in pathogen killing, strengthening of plant cell walls, triggering hypersensitive cell death and systemic resistance signaling (Shetty et al, 2007). An increase in the investigated physiological traits revealed that biochemical defense responses shown by cowpea were a reaction of damage caused by M. phaseolina, but not as an efficient defense mechanism resulting compatible host-pathogen interaction in positive control. Soil amendments markedly decreased levels of antioxidant enzymes that could be related to the fact that when antagonistic fungi and allelopathic plant leaf biomass were applied, these agents normalized the effects so cowpea plant would have to face in case of pathogen attack.

Conclusions

It was concluded that application of T. harzianum in combination with leaf biomass of A. indica was effective and environmentally friendly method of managing charcoal rot of cowpea. Thus, reduction in disease incidence and improvement in plant growth through altering host plant physiology resulted in increasing resistance in the cowpea plant through suppression of ROS scavenging enzymes against charcoal rot disease.

References

Baka ZA (2010) Antifungal activity of six Saudi medicinal plant extracts against five phyopathogenic fungi. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot 43:736–743

Carpinella MC, Giorda LM, Ferrayoli CG, Palacios SM (2003) Antifungal effects of different organic extracts from Melia azedarach L. on phytopathogenic fungi and their isolated active components. J Agric Food Chem 1:2506–2511

Colville L, Smirnoff N (2008) Antioxidant status, peroxidase activity, and PR protein transcript levels in ascorbate-deficient Arabidopsis thaliana vtc mutants. J Exp Bot 59:3857–3868

Dickerson DP, Pascholati SF, Hagerman AE, Butler LG, Nicholson RL (1984) Phenylalanine ammonia lyase and hydroxycinnamate: CoA ligase in maize mesocotyls inoculated with Helminthosporium maydis or Helminthosporium carbonum. Physiol Plant Pathol 25:111–123

Gaige AR, Ayella A, Shuai B (2010) Methyl jasmonate and ethylene induce partial resistance in Medicago truncatula against the charcoal rot pathogen Macrophomina phaseolina. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 74:412–418

Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I (2006) Overview of mechanisms and uses of Trichoderma spp. Phytopathology 96:190–194

Heiser I, Oßwald W, Elstner EF (1998) The formation of reactive oxygen species by fungal and bacterial phytotoxins. Plant Physiol Biochem 36:703–713

Hossain MA, Al-Toubi WA, Weli AM, Al-Riyami QA, Al-Sabahi JN (2013) Identification and characterization of chemical compounds in different crude extracts from leaves of Omani neem. J Taibah Univ Sci 7:181–188

Jabeen K, Javaid A, Ahmad E, Athar M (2011) Antifungal compounds from Melia azedarach leaves for management of Ascochyta rabiei, the cause of chickpea blight. Nat Prod Res 25:264–276

Khaledi N, Taheri P (2016) Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma harzianum against soybean charcoal rot caused by Macrophomina phaseolina. J Plant Prot Res 56:21–31

Khalili E, Sadravi M, Naeimi SH, Khosravi V (2012) Biological control of rice brown spot with native isolates of three Trichoderma species. Braz J Microbiol 43:297–305

Khodary A (2004) The effect of MnCl2 filler on the physical properties of polystyrene films. Physica B: Condens Matter 344:297–306

Latha P, Anand T, Ragupathi N, Prakasam V, Samiyap PR (2009) Antimicrobial activity of plant extracts and induction of systemic resistance in tomato plants by mixtures of PGPR strains and Zimmu, leaf extract against Alternaria solani. Biol Control 50:85–93

Maehly AC, Chance B (1967) In: Glick D (ed) Methods of biochemical analysis. Inter Science Publications, New York, pp 357–424

Mayek-Perez PN, Lopez CC, Gonzales CM, Garcia ER, Acosta GJ, De VOM, Simpson J (2001) Variability of Mexican isolates of Macrophomina phaseolina based on pathogenesis and AFLP genotype. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 59:257–264

Mayer AM, Harel E, Shaul RB (1965) Assay of catechol oxidase: a critical comparison of methods. Phytochemistry 5:783–789

Mensack MM, Fitzgerald VK, Ryan EP, Lewis MR, Thompson HJ, Brick MA (2010) Evaluation of diversity among common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) from two centers of domestication using omics technologies. BMC Genomics 11:686

Naglot A, Goswami S, Rahman I, Shrimali DD, Yadav KK, Gupta VK, Rabha AJ, Gogoi HK, Veer V (2015) Antagonistic potential of native Trichoderma viride strain against potent tea fungal pathogens in North East India. Plant Pathol J 31:278

Petit AN, Vaillant N, Boulay M, Clement C, Fontaine F (2006) Alteration of photosynthesis in grapevines affected by Esca. Phytopathology 96:1060–1066

Sales MD, Costa HB, Fernandes PM, Ventura JA, Meira DD (2016) Antifungal activity of plant extracts with potential to control plant pathogens in pineapple. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 6:26–31

Shetty NP, Mehrabi R, Lutken HA, Haldrup A, Kema GH, Collenge DP, Jorgenson H (2007) Role of hydrogen peroxide during the interaction between the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen Septoria tritici and wheat. New Physiol 174:637

Vinale FK, Sivasithamparam EL, Ghisalberti R, Marra R, Woo SL, Lorito M (2008) Trichoderma plant-pathogen. Soil Biol Biochem 40:1–10

Woo SL, Scala F, Ruocco M, Lorito M (2006) The molecular biology of the interactions between Trichoderma, phytopathogenic fungi and plants. Phytopathology 96:181–185

Acknowledgements

Authors highly acknowledge the services of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences, University of the Punjab, Pakistan, for the present research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS and AJ: Participated in deigning experiment, statistically analyzing data and writing manuscript. MM and ZAA: Conducted experiment and compiled data. MR: Helped in conducing physiological assays. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoaib, A., Munir, M., Javaid, A. et al. Anti-mycotic potential of Trichoderma spp. and leaf biomass of Azadirachta indica against the charcoal rot pathogen, Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid in cowpea. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 28, 26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0031-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0031-6