Abstract

Background

The 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was introduced to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in Western Australian (WA) Aboriginal people in 2001. PCV13 replaced PCV7 in July 2011, covering six additional pneumococcal serotypes; however, IPD rates remained high in Aboriginal people in WA. Upper respiratory tract pneumococcal carriage can precede IPD, and PCVs alter serotype distribution.

Methods

To assess the impact of PCV13 introduction, identify emerging serotypes, and assess risk factors for carriage, nasopharyngeal swabs and information on demographic characteristics, health, medication and living conditions from Aboriginal children and adults across WA from August 2008 to November 2014 were collected. Bacteria were cultured using selective media and pneumococcal isolates were serotyped by Quellung reaction. Risk factors were analysed by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

One thousand five hundred swabs pre- and 1385 swabs post-PCV13 introduction were collected. Pneumococcal carriage was detected in 66.8% of children <5 years old and 53.2% of 5–14 year-olds post-PCV13, compared with pre-PCV13 prevalence of 72.2% and 49.4%, respectively. The prevalence of PCV13-non-PCV7 serotypes decreased in children <5 years old from 13.5% pre-PCV13 to 5.8% post-PCV13 (p < 0.01), and from 8.4% to 6.1% in children 5–14 years old (p > 0.05). The most common serotypes post-PCV13 were 11A (prevalence 4.0%), 15B (3.5%), 16F (3.5%), and 19F (3.2%).

Risk of detection of pneumococcal carriage increased until age 12 months (odds ratio [OR] 4.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.39–7.33), with nasal discharge (OR 2.49 [95% CI 2.00–3.09]), residence in a remote community (OR 2.21 [95% CI 1.67–2.92]) and household crowding (OR 1.36 [95% CI 1.11–1.67]). Recent antibiotic use was negatively associated with pneumococcal carriage (OR 0.48 [95% CI 0.33–0.69]). Complete resistance to penicillin was present among isolates of serotypes 19A (6.0%), 19F (2.3%) and non-serotypeable isolates (1.9%). Serotype 23F and newly emerged serotype 7B isolates showed high rates of resistance to cotrimoxazole, erythromycin and tetracycline (86.9%, 86.9%, 82.0%, respectively for 23F, 100.0%, 100.0% and 93.3% for 7B).

Conclusion

Since PCV13 replaced PCV7, carriage of PCV13-non-PCV7 serotypes decreased significantly among children <5 years old, those most likely to have received PCV13, and to a lesser extent in older people. Known risk factors for carriage including crowding and young age remain in the Aboriginal population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is estimated to cause up to a million deaths from invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) per year, worldwide [1]. While the greatest burden of IPD is concentrated in resource-poor countries, Australian Aboriginal people in central and western regions of Australia experience an almost five-fold greater incidence of IPD than non-Aboriginal Australians [2]. In addition to high rates of IPD, Aboriginal children also experience a high burden of other manifestations of pneumococcal disease, including pneumonia and otitis media (OM) [3].

Vaccination to prevent IPD is effective against targeted serotypes, but limited by the existence of at least 93 serotypes of S. pneumoniae, each differentiated by its polysaccharide capsule. The 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7, covering serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F) was introduced for Australian Aboriginal children at 2, 4 and 6 months old in 2001 with a booster dose of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV, covering PCV7 serotypes and 1, 2, 3, 5, 7F, 8, 9 N, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 17F, 19A, 20, 22F, and 23F) scheduled at 18 months old. A catch-up schedule was in place for children <2 years old and for children <5 years old with predisposing medical conditions. All Australian children became eligible in 2005 for 3 primary doses of PCV7 with no scheduled booster. Following the introduction of PCV7, IPD rates initially fell in the Aboriginal population in Western Australia (WA) but subsequently increased in adults [2]. The observed increase was accompanied by a rise in IPD caused by non-PCV7 serotypes [4, 5].

On 1 July 2011, PCV7 was recalled and immediately replaced with PCV13 (covering the six additional serotypes 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F and 19A). For Aboriginal children, a fourth dose of PCV13 at 18 months old replaced the 23vPPV booster over a transition period from September 2011 to October 2012 [6]. Following PCV13 introduction in Australia, IPD rates appeared to decrease; however, rates in IPD caused by non-PCV13 serotypes increased [4, 7].

Nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae is generally asymptomatic but is an important precursor to pneumococcal disease. Pneumococcal carriage studies have been used to monitor the prevalence and distribution of S. pneumoniae serotypes in WA, and for surveillance of antibiotic resistant strains. Despite introduction of the PCV program, pneumococcal carriage rates remain high among Aboriginal people [8, 9], and have been observed to be higher in Aboriginal children than in non-Aboriginal children [10]. In WA, carriage rates were 71.9% and 34.6% among Aboriginal children <5 years old and people ≥5 years old, respectively, after introduction of PCV7 [9]. Most pneumococcal carriage serotypes in WA in the PCV7 era were non-PCV7 serotypes, the most common being 19A, 16F and 6C [9].

Given that the PCV vaccination program does not appear to have reduced overall IPD rates in the Aboriginal population in age groups other than children <5 years [4], it is important to identify risk factors for carriage of S. pneumoniae to help identify further opportunities for prevention of pneumococcal disease. Previously, household crowding and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) have been identified as risk factors [11]. The authors have monitored pneumococcal carriage in Aboriginal people living in WA since 2008. This study describes the prevalence of overall carriage and that of individual serotypes in the WA Aboriginal population before and after the introduction of PCV13, along with epidemiological risk factors for carriage.

Methods

Study population

Aboriginal people make up about 3% of the total WA population (total 2.2 million people); 39% live in the Perth metropolitan area, the remainder in regional towns or scattered sparsely across remote areas of WA. The WA climate varies, from tropical in the north to inland deserts and warm temperate southwest coastal regions.

Sample and data collection and laboratory analysis

The surveillance study has been described previously [9]. In brief, nasopharyngeal swabs or nose blown samples [12] were collected opportunistically from Aboriginal people of all ages in communities across WA from August 2008 to November 2014. Participants were defined as having participated “pre-PCV13” introduction (from study start until 30 June 2011) or “post-PCV13” (from 1 July 2011 onwards). Demographic, environmental and health data including details on smoking behaviour and exposure, numbers of co-resident household members, recent medication and illness were collected by completing a questionnaire during face-to-face interviews. Swabs were cultured on selective media. S. pneumoniae isolates were confirmed by optochin susceptibility. Two pneumococcal isolates (or more, if morphologically distinct) per positive culture were subcultured and serotyped by the Quellung reaction using antisera from the Statens Serum Institut, Denmark [13]. Isolates that could not be serotyped by Quellung reaction were referred to as “non-serotypeable”. Antimicrobial susceptibilities were tested by disc diffusion. E-test (bioMérieux Diagnostics, France) was performed where reduced antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by disc diffusion. Resistance to antimicrobials was classified according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [14]. Breakpoints for intermediate and complete resistance to penicillin (collectively termed “non-susceptibility”) were 4 μg/mL and 8 μg/mL, respectively.

The remoteness (metropolitan, regional or remote) of communities was classified using the Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Structure [15]. Household crowding was defined as ≥5 people sharing accommodation on the night prior to sample collection. Co-residence with a child was defined as sharing with at least one child <5 years old on the previous night. Respiratory symptoms were defined as any cough, sore throat, or blocked or runny nose as reported by the participant or guardian. Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure was considered present if it was reported that any co-resident was a smoker. The immunization status of children was determined from the Australian Childhood Immunization Register (ACIR), accessed using the participant’s name and date of birth. Children were classified as vaccinated with PCV7 or PCV13 if they had received at least two doses of the relevant vaccine at least 2 weeks prior to specimen collection.

Statistical analysis

All descriptive and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States of America [USA]) and Stata 11 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Results of culture and serotyping were aggregated according to serotype to calculate the prevalence of individual serotypes among all study participants. Differences in crude proportions were compared using χ2 test; statistical significance was considered if p < 0.05. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify independent risk factors for carriage of serotypeable pneumococci. Variables were included, if identified previously in the literature as risk factors for carriage, in a backwards stepwise model, eliminating variables using a cut-off value of p > 0.05. Vaccination status was excluded from the risk factor analysis due to poor recovery of vaccination records and low number of PCV13-vaccinated children (see Results section). The influence of age on carriage risk was modelled using a spline function with knots at age 1 year and at 20 years, based on previous findings of a peak in carriage at 12 months of age in this particular population [9]. The influence of calendar time was modelled as a linear continuous variable, with the influence of the PCV13 program on carriage explored using a simple marginal spline function with a single knot corresponding to 1 July 2011, the date of PCV13 introduction.

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children Ethics Committee, the Western Australian Country Health Service Board Research Ethics Committee and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee. Approval to approach communities in the Kimberley region was granted by the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum. Consent was sought from adult participants and from the parents or guardians of child participants.

Results

Study population

In total 2885 nasopharyngeal samples (2824 nasopharyngeal swabs; 60 nose blown samples; 1 unknown) were collected: 1500 before the introduction of PCV13 on 1 July 2011, and 1385 afterwards. Most participants reported being healthy on the day of participation, while 31.5% had visible nasal discharge and 8.4% reported respiratory symptoms (Table 1). Most samples were collected among remote residents (78.2%). Crowding (61.7%) and co-residence with children (73.5%) were common across all age groups. Any ETS exposure was reported by 65.3% of participants; 22.9% reported exposure to indoor ETS, and 55.6% of adult respondents reported smoking themselves. Recent antibiotic use was reported by 7.6% of participants. Immunization status could be determined for only 628 (59.1%) participants <5 years old and 488 (51.5%) participants 5–14 years old. Among PCV7 age-eligible children whose immunization status was available, 504 (89.4%) of those <5 years old and 302 (74.6%) of those aged 5–14 years were vaccinated with PCV7 (Table 1). Among children eligible for PCV13 whose immunization status was known, 37 (59.7%) were vaccinated with at least two doses of PCV13 and 64 (98.5%) had received at least one dose. A combination of PCV7 and PCV13 (at least one dose of each) was received by 66 (6.8%) children.

Carriage prevalence

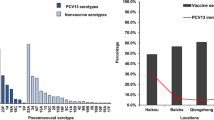

Compared to the pre-PCV13 period, carriage of any pneumococcal serotype was less common in the post-PCV13 period among adults (19.5% versus 9.9%, p < 0.01) and to a lesser extent among children <5 years old (72.2% versus 66.8%, p = 0.054) but not in children 5–14 years old (49.4% versus 53.2%, p = 0.24). Carriage of PCV13-non-PCV7 serotypes was less common post-PCV13 introduction among children <5 years old (13.5% versus 5.8%, p < 0.01; Table 1, Fig. 1). There was also a numerical reduction in carriage of vaccine serotypes in older age groups (Table 1). S. pneumoniae was recovered from 46.8% of nasopharyngeal swabs and 56.7% of nose-blown samples.

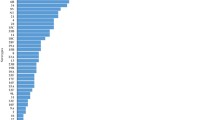

Culture identified 1357 pneumococcus-positive specimens (47.0%) giving 1590 distinct pneumococcal isolates, 1374 (86.4%) of which were serotypeable (Table 2). The most common of the 48 serotypes detected were 16F (prevalence 3.8%), 6C (3.6%), 11A (3.3%), 19F (3.0%), 19A (2.9%) and 15B (2.6%). Several PCV13 serotypes decreased in frequency post-PCV13 introduction in children <5 years old: PCV7 type 23F (4.8% versus 1.8%, p < 0.05), PCV13-non-PCV7 types 6A (3.6% versus 1.4%, p < 0.05) and 19A (7.7% versus 3.2%, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Reductions in PCV13 types were also observed in participants ≥5 years old, to a lesser extent than that seen in children <5 years (15.5% to 12.1% in 5–14 years, p = 0.12; 4.1% to 2.2% in ≥15 years group, p = 0.10, Table 1).

Carriage of more than one serotype was identified in 131 (4.5%) specimens. Non-serotypeable isolates were detected in addition to a serotypeable isolate in 81 (2.8%) specimens. The prevalence of a non-serotypeable pneumococcus in the absence of serotypeable strains was lower post-PCV13 (4.7% versus 3.9%, p = 0.06).

Among 36 non-PCV13 serotypes identified, the prevalence of 11A (4.8% versus 8.4%, p < 0.05), 15B (2.1% versus 7.0%, p < 0.01) and 21 (0.9% versus 2.6%, p < 0.05) increased significantly among children <5 years old while 7B and 29 were only detected post-PCV13 (2.0% and 1.8% respectively, both p < 0.05). Serotypes 6C and 23B were detected less frequently post-PCV13 introduction in children <5 years old (8.0% versus 3.4%, p < 0.05 and 5.0% versus 1.8%, p < 0.05; Fig. 2).

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Non-susceptibility to penicillin was present in 25.2% of isolates, including in 84.9% of serotype 19F isolates. Complete resistance to penicillin was uncommon, found among isolates of serotypes 19A (6.0%), 19F (2.3%) and non-serotypeable isolates (1.9%) only (Table 2). Serotype 23F isolates showed high rates of resistance to cotrimoxazole, erythromycin and tetracycline (86.9%, 86.9% and 82.0%, respectively). Multi-resistance to three or more antibiotics was recorded in 102 serotypeable isolates (7.4%) overall; mainly serotype 15A isolates (68.0%) and serotype 23F isolates (88.5%). Isolates of serotype 7B (n = 15), which were only detected post-PCV13, were all resistant to cotrimoxazole and erythromycin, non-susceptible to penicillin and 93.3% were resistant to tetracycline (Table 2). Overall, susceptibility of strains to antimicrobials did not change significantly after introduction of PCV13, apart from a decrease in cotrimoxazole resistance (26.1% to 21.3%, p < 0.05, Table 2). Multi-resistance was present in 17.6% of non-serotypeable isolates.

Risk factors for pneumococcal carriage

Carriage of any serotypeable pneumococcus was more common among males (OR 1.56 [95% CI 1.35–1.81]) and those who were carriers of Haemophilus influenzae (OR 10.29 [95% CI 8.60–12.30]) and Moraxella catarrhalis (OR 7.10 [95% CI 6.01–8.39]) compared with those who were not (Table 3). Pneumococcal carriage was detected more commonly among those reporting respiratory symptoms (OR 1.48 [95% CI 1.14–1.94]), in the presence of nasal discharge (OR 4.84 [95% CI 4.01–5.74]), among those living in a remote community (OR 1.86 [95% CI 1.41–2.35]) and those living in crowded households (OR 1.35 [95% CI 1.15–1.58]). Pneumococcal carriage was detected less commonly among those who reported recent antibiotic use (OR 0.73 [95% CI 0.55–0.98]) and in Staphylococcus aureus carriers (OR 0.56 [95% CI 0.44–0.72]) than among those who were not (Table 3).

In the multivariable analysis, significant independent predictors of carriage of any serotypeable pneumococcus included the presence of nasal discharge (OR 2.49 [95% CI 2.00–3.09]), crowding (OR 1.36 [95% CI 1.11–1.67]) and remote versus urban residence (OR 2.21 [95% CI 1.67–2.92]). Recent receipt of antibiotics was associated with lower odds of detection of pneumococcal carriage (OR 0.48 [95% CI 0.33–0.69]). After modelling for the influence of age using the spline function, there was a significant risk of carriage of pneumococcus up to age 1 year (OR 4.19 [95% CI 2.39–7.33]), which then decreased from 1 year to 19 years (14.7% decline per year; OR 0.85 [95% CI 12.9–16.4], Table 3). Adjusting for other factors, there was no evidence that introduction of PCV13 was associated with an overall reduction in all pneumococcal serotypes (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The overall prevalence of carriage of pneumococci among WA Aboriginal children and adults remains high following the introduction of PCV13. For children, pneumococcal carriage has remained relatively stable over time, with carriage increasing in infants until around their first birthday and then slowly declining with increasing age to adulthood (Table 3).

IPD rates caused by non-PCV serotypes have increased since the introduction of PCV13 nationwide [4, 7]. In WA, the continuing high rates of carriage despite vaccination indicate an ongoing contribution of environmental factors to acquisition of pneumococcus.

The main factors associated with detection of pneumococcal carriage in our analysis were young age, presence of nasal discharge and household crowding. The age distribution of pneumococcal carriage—increasing each month of the first year and declining slowly thereafter—has been observed previously in Aboriginal children in WA [9] and correlates with the observed age distribution of OM which is hyper-endemic in this population [3, 16]. Nasal discharge was strongly associated with detection of pneumococcal carriage (Table 3). The authors speculate that pneumococcus plays a causative role in nasal discharge; however, it is also possible that nasal discharge merely improves detection of carriage. In either case, reinforcement of hygiene practices would be important for limiting transmission of pneumococcal strains.

The relationship between household crowding and pneumococcal carriage has been reaffirmed in this study. Previously crowding was linked with high carriage in a study conducted in communities surrounding Kalgoorlie in WA [17] and in other indigenous communities including Alaska Native people [18]. While not shown to be an independent risk factor in this analysis, ETS exposure was reported more frequently among those with pneumococcal carriage (univariable OR 1.24 [95% CI 1.06–1.46]) and this has previously been associated with both pneumococcal carriage [18] and OM in Aboriginal children [8, 19, 20]. These associations reinforce the need to promote healthy living conditions for Aboriginal people and the importance of smoking prevention programs.

Recent antibiotic use was strongly negatively associated with detection of pneumococcal carriage (Table 3). There was no appreciable change in rates of antibiotic resistance among carriage isolates over the study, apart from a decrease in resistance to cotrimoxazole in the post-PCV13 period (Table 2). Crude χ2 tests of carriage of non-susceptible strains of pneumococcus or multi-resistant strains versus recent antibiotic use identified no significant differences between the groups (data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that recent antibiotic use may be protective against pneumococcal carriage.

After adjusting for age, date, gender, remoteness, and other factors, there was no evidence that the prevalence of carriage of all serotypeable pneumococci across all age groups decreased after introduction of PCV13 (Table 3). Among children <5 years old, those most likely to have been vaccinated with PCV13, the prevalence of carriage across all serotypes did not change significantly (Table 1) but there was evidence of a significant decrease in carriage of both PCV7 and PCV13 serotypes (Table 1, Fig. 2). A similar reduction in vaccine serotypes was previously reported in Alaska Native children [21]. It appears that non-vaccine strains are replacing vaccine-type strains after PCV13 introduction, rather than PCV13 reducing carriage overall. This study was unable to investigate possible herd immunity in more detail, particularly in infants <6 months old, due to low enrolment numbers in this age group. Carriage of PCV13 serotypes was also numerically reduced in the older age groups studied (Table 1), albeit to a lesser extent than in children <5 years old. Post-PCV13 vaccination coverage was estimated at ≥82% among 5–14 year olds (Table 1), and the Australian National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance estimates PCV vaccination coverage in Aboriginal children in WA at >88% [22]. The numerical reduction in PCV serotypes in older study participants is consistent with an indirect effect of PCV13.

There were a number of strengths to this study, chiefly the large sample size, spread over a broad geographic region over several years. However there were also several limitations. The opportunistic nature of sampling meant the study did not achieve similar coverage of inhabitants in all communities, and certain seasons were favoured for visiting certain areas due to easier access by road/air compared to rainy seasons. This meant some regions/seasons may have been comparatively under-represented in some analyses. Immunization status for all children in this study could not be ascertained, due to an inability to identify ACIR records for some participants. This was primarily due to the method used to access immunization data: participants were identified by name and date of birth, as documented on records during interviews. It is common among Aboriginal communities for individuals to be identified by several different names and spellings can vary for the same person; thus the data could not always be matched to a record on the ACIR database.

Because most children <5 years old post-PCV13 appeared to have received at least one dose of PCV13, the reduction in PCV13-non-PCV7 serotypes may have been directly influenced by PCV13 vaccination. However, greater decreases in PCV13 serotype carriage were noted in Alaskan [23] and Massachusetts children [24] following PCV13 introduction. Due to the uncertainty in vaccination status for a large proportion of participants, and the small number of children confirmed as PCV13 vaccinated (n = 37, Table 2), vaccination status was not included as a variable in the risk factor analysis. Another limitation of the study was the lack of detailed information to allow accurate assessment of indirect effects within households. It would be highly informative to analyse carriage and possible transmission between household members, and to assess the impact of vaccination status of children on other household members. However, in the communities studied, movement of family members between houses and communities is often dynamic rather than static, so such an analysis is likely to be imprecise.

Despite observing reduced carriage of 6C and 19A in children, these serotypes remained among the most common serotypes carried following PCV13 introduction. The reduction in carriage of serotypes 6A, 23F and 19A is plausibly attributable to PCV13 as they are vaccine serotypes. The reduction in 6C in children <5 years old may be attributable to cross-protection from 6A which is covered by PCV13 [25]. The increase in non-vaccine types, most notably 11A, 7B and 15B warrants further monitoring. Increases in 11A and serogroup 15 have been reported from other regions and countries. IPD caused by serogroup 15 increased in Norway after PCV13 introduction [26]. Serotype 11A was identified as an emerging serotype in the Northern Territory Aboriginal population following PCV7 introduction [27], and carriage of 11A also increased in Sweden and Japan following PCV13 introduction [28, 29]. Moreover, high rates of antimicrobial resistance among serotypes 23F, 7B and 9 V are particularly concerning and warrant close surveillance (Table 2).

Conclusions

While PCV13 appears to have influenced the distribution of carriage serotypes among Aboriginal children in WA, the overall rate of pneumococcal carriage remains high across all age groups, with replacement of vaccine serotypes with emerging non-vaccine serotypes. The relevance of emerging carriage serotypes to IPD and more common pneumococcal manifestations of OM and pneumonia needs to be carefully assessed to properly understand the impact of conjugate vaccination.

Abbreviations

- 23vPPV:

-

23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine

- ACIR:

-

Australian Childhood Immunisation Register

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ETS:

-

Environmental tobacco smoke

- IPD:

-

Invasive pneumococcal disease

- OM:

-

Otitis media

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCV13:

-

13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PCV7:

-

7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- WA:

-

Western Australia

References

World Health Organization. Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper - 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:129–44.

Lehmann D, Willis J, Moore HC, Giele C, Murphy D, Keil AD, et al. The changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Western Australians from 1997 through 2007 and emergence of non-vaccine serotypes. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1477–86.

Lehmann D, Weeks S, Jacoby P, Elsbury D, Finucane J, Stokes A, et al. Absent otoacoustic emissions predict otitis media in young Aboriginal children: a birth cohort study in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in an arid zone of Western Australia. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:32.

de Kluyver R, Enhanced Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Surveillance Working Group. Invasive pneumococcal disease surveillance Australia, 1 January to 31 March 2015. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2015;39:E308–11.

Giele CM, Keil AD, Lehmann D, Van Buynder PG. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Western Australia: emergence of serotype 19A. Med J Aust. 2009;190:166.

The Australian Immunisation Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2013.

Jayasinghe S, Menzies R, Chiu C, Toms C, Blyth CC, Krause V, et al. Long-term impact of a "3 + 0" schedule for 7- and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease in Australia, 2002-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:175–83.

Mackenzie GA, Leach AJ, Carapetis JR, Fisher J, Morris PS. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carriage of respiratory bacterial pathogens in children and adults: cross-sectional surveys in a population with high rates of pneumococcal disease. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:304.

Collins DA, Hoskins A, Bowman J, Jones J, Stemberger NA, Richmond PC, et al. High nasopharyngeal carriage of non-vaccine serotypes in Western Australian Aboriginal people following 10 years of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82280.

Dunne EM, Carville K, Riley TV, Bowman J, Leach AJ, Cripps AW, et al. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in Western Australia carry different serotypes of pneumococci with different antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Pneumonia. 2016;8:1–9.

Jacoby P, Carville KS, Hall G, Riley TV, Bowman J, Leach AJ, et al. Crowding and other strong predictors of upper respiratory tract carriage of otitis media-related bacteria in Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:480–5.

Leach AJ, Stubbs E, Hare K, Beissbarth J, Morris PS. Comparison of nasal swabs with nose blowing for community-based pneumococcal surveillance of healthy children. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2081–2.

Watson K, Carville K, Bowman J, Jacoby P, Riley TV, Leach AJ, et al. Upper respiratory tract bacterial carriage in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in a semi-arid area of Western Australia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:782–90.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: seventh informational supplement M100-S17. Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA: CLSI; 2007.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Structure. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2011.

Leach AJ, Wigger C, Andrews R, Chatfield M, Smith-Vaughan H, Morris PS. Otitis media in children vaccinated during consecutive 7-valent or 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination schedules. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:200.

Leach AJ, Wigger C, Beissbarth J, Woltring D, Andrews R, Chatfield MD, et al. General health, otitis media, nasopharyngeal carriage and middle ear microbiology in Northern Territory Aboriginal children vaccinated during consecutive periods of 10-valent or 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;86:224–32.

Reisman J, Rudolph K, Bruden D, Hurlburt D, Bruce MG, Hennessy T. Risk factors for pneumococcal colonization of the nasopharynx in Alaska Native adults and children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3:104–11.

Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Broides A, Blancovich I, Peled N, Dagan R. The contribution of smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae carriage in children and their mothers. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:897–903.

Jacoby PA, Coates HL, Arumugaswamy A, Elsbury D, Stokes A, Monck R, et al. The effect of passive smoking on the risk of otitis media in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in the Kalgoorlie-Boulder region of Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;188:599–603.

Bruce MG, Singleton R, Bulkow L, Rudolph K, Zulz T, Gounder P, et al. Impact of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) on invasive pneumococcal disease and carriage in Alaska. Vaccine. 2015;33:4813–9.

National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Coverage estimates - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children NSW: NCIRS; 2017 [updated 20 Apr 2017]. Available from: http://www.ncirs.edu.au/provider-resources/coverage-information/coverage-estimates-indigenous-children/.

Gounder PP, Bruce MG, Bruden DJ, Singleton RJ, Rudolph K, Hurlburt DA, et al. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae-Alaska, 2008-2012. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1251–8.

Loughlin AM, Hsu K, Silverio AL, Marchant CD, Pelton SI. Direct and indirect effects of PCV13 on nasopharyngeal carriage of PCV13 unique pneumococcal serotypes in Massachusetts' children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:504–10.

Cooper D, Yu X, Sidhu M, Nahm MH, Fernsten P, Jansen KU. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) elicits cross-functional opsonophagocytic killing responses in humans to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6C and 7A. Vaccine. 2011;29:7207–11.

Steens A, Bergsaker MAR, Aaberge IS, Rønning K, Vestrheim DF. Prompt effect of replacing the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine with the 13-valent vaccine on the epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Norway. Vaccine. 2013;31:6232–8.

Leach AJ, Morris PS, McCallum GB, Wilson CA, Stubbs L, Beissbarth J, et al. Emerging pneumococcal carriage serotypes in a high-risk population receiving universal 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine since 2001. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:121.

Galanis I, Lindstrand A, Darenberg J, Browall S, Nannapaneni P, Sjöström K, et al. Effects of PCV7 and PCV13 on invasive pneumococcal disease and carriage in Stockholm. Sweden Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1208–18.

Kawaguchiya M, Urushibara N, Aung M, Morimoto S, Ito M, Kudo K, et al. Emerging non-PCV13 serotypes of noninvasive Streptococcus pneumoniae with macrolide resistance genes in northern Japan. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;9:66–72.

Acknowledgements

We thank the communities and the staff of Aboriginal Medical Services and Community Health Services who facilitated our study visits. We are grateful to all the study participants.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by WA Department of Health through the Collaboration for Applied Research and Evaluation (CARE) and NHMRC Project Grant #545232. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets from the current study can be shared by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception, generation and design of the research plan: DL, AJL, AH. Data collection: AH, DC, JB, KS, NAS. Data analysis: DC, TS. Drafting of manuscript: DC, TS, DL. All authors performed critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children Ethics Committee, the Western Australian Country Health Service Board Research Ethics Committee and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee. Local approval to approach communities in the Kimberley region was granted by the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum. Consent was sought from parents or guardians of children included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DL has previously been a member of the GSK Australia Pneumococcal-Haemophilus influenzae-Protein D conjugate vaccine (“PhiD-CV”) Advisory Panel, has received support from Pfizer Australia and GSK Australia to attend conferences, has received an honorarium from Merck Vaccines to give a seminar at their offices in Pennsylvania and support to attend a conference, and is an investigator on an investigator-initiated research grant funded by Pfizer Australia. AJL has received research funding and support to attend conferences from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer Australia. A Hoskins has received support to attend conferences from Pfizer Australia. All other authors have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, D.A., Hoskins, A., Snelling, T. et al. Predictors of pneumococcal carriage and the effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the Western Australian Aboriginal population. Pneumonia 9, 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-017-0038-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-017-0038-x