Abstract

Background

To determine the prevalence of carriage of respiratory bacterial pathogens, and the risk factors for and serotype distribution of pneumococcal carriage in an Australian Aboriginal population.

Methods

Surveys of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis were conducted among adults (≥16 years) and children (2 to 15 years) in four rural communities in 2002 and 2004. Infant seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (7PCV) with booster 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine was introduced in 2001. Standard microbiological methods were used.

Results

At the time of the 2002 survey, 94% of eligible children had received catch-up pneumococcal vaccination. 324 adults (538 examinations) and 218 children (350 examinations) were enrolled. Pneumococcal carriage prevalence was 26% (95% CI, 22-30) among adults and 67% (95% CI, 62-72) among children. Carriage of non-typeable H. influenzae among adults and children was 23% (95% CI, 19-27) and 57% (95% CI, 52-63) respectively and for M. catarrhalis, 17% (95% CI, 14-21) and 74% (95% CI, 69-78) respectively. Adult pneumococcal carriage was associated with increasing age (p = 0.0005 test of trend), concurrent carriage of non-typeable H. influenzae (Odds ratio [OR] 6.74; 95% CI, 4.06-11.2) or M. catarrhalis (OR 3.27; 95% CI, 1.97-5.45), male sex (OR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.31-3.73), rhinorrhoea (OR 1.66; 95% CI, 1.05-2.64), and frequent exposure to outside fires (OR 6.89; 95% CI, 1.87-25.4). Among children, pneumococcal carriage was associated with decreasing age (p < 0.0001 test of trend), and carriage of non-typeable H. influenzae (OR 9.34; 95% CI, 4.71-18.5) or M. catarrhalis (OR 2.67; 95% CI, 1.34-5.33). Excluding an outbreak of serotype 1 in children, the percentages of serotypes included in 7, 10, and 13PCV were 23%, 23%, and 29% (adults) and 22%, 24%, and 40% (2-15 years). Dominance of serotype 16F, and persistent 19F and 6B carriage three years after initiation of 7PCV is noteworthy.

Conclusions

Population-based carriage of S. pneumoniae, non-typeable H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis was high in this Australian Aboriginal population. Reducing smoke exposure may reduce pneumococcal carriage. The indirect effects of 10 or 13PCV, above those of 7PCV, among adults in this population may be limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for an estimated 14.5 million episodes of serious disease and 826,000 deaths annually among children aged 1 to 59 months [1]. The burden of pneumococcal disease in older age groups is unknown. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of pneumonia [2, 3] while both non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (indicated subsequently as H. influenzae) and Moraxella catarrhalis are associated with exacerbations of chronic obstructive airways disease [4, 5]. Among Australia's Northern Territory (NT) Aboriginal population, respiratory causes are responsible for 18% of deaths [6]. Aboriginal adults and older children also experience high rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) [7].

Respiratory infection in individuals is related to episodes of pneumococcal carriage acquisition [8, 9]. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) reduce carriage of vaccine serotypes (VT) with increased carriage of non-vaccine serotypes [10, 11]. The importance of the impact of PCV on carriage has been highlighted by the large indirect effects observed following introduction of 7-valent PCV (7PCV) in the United States [12]. However, the characteristics of population-level pneumococcal carriage epidemiology which influence the indirect effects of PCV are not well described. Whether such indirect effects can be expected in populations with different pneumococcal carriage epidemiology is unknown.

Data concerning nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis in high-risk populations, such as Aboriginal adults and older children, are limited. The NT of Australia introduced 7PCV and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23PPV) for Aboriginal children in late 2001. Despite high levels of vaccination coverage, a study describing the indirect effects of universal pneumococcal vaccination in the four Aboriginal communities involved in this study documented the same VT carriage prevalence in 2002 and 2004 [13]. Further aims of this study were to determine the age-specific prevalence of respiratory bacterial carriage in children and adults, as well as the risk factors for and serotype distribution of pneumococcal carriage among those aged 2 years and over.

Methods

Study population

We performed two surveys in the four main communities (> 90% of the total population) on the Tiwi Islands, 70 km north of Darwin, off the coast of the NT. In 2002, the population was 2,204 and 92% of individuals identified as Aboriginal. NT immunization policy recommended 23PPV for Aboriginal adults > 15 years of age. A 7PCV catch-up campaign for those < 2 years of age began in August 2001 along with three doses of 7PCV at 2, 4, and 6 months of age and booster 23PPV at 18 months of age.

Procedures

Participants were enrolled in 2002 (August - November) and these individuals were followed up, along with others in 2004 (March - May). The 2002 and 2004 surveys were conducted during dry and wet seasons respectively. Eligibility criteria were: permanent residence, Aboriginal ethnicity, and age ≥2 years. Purposive sampling aimed to obtain equal numbers of 'typical' males and females in each of two groups; adults (≥16 years of age) and children (≥2 and < 16 years of age). To obtain more precise estimates of prevalence among adults with lower carriage than children, sampling aimed to enrol 1.5 times the number of adults than children. We visited a range of work places, public locations, schools and private residences.

Written informed consent was obtained after participants read the study information or had it explained to them in English or Tiwi. When consent was discussed with adults, consent was also sought for enrolment of their children. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Tiwi Health Board and the NT Department of Health and Community Services, Human Research Ethics Committee.

Demographic and risk factor data, as well as information from community clinic records, were recorded on standard forms. Dates of pneumococcal and influenza vaccination were extracted from clinic records, the community clinic and NT immunisation databases.

Microbiological methods

Nasopharyngeal swabs and culture used methods similar to those proposed by WHO [14]. Methodological variations were: swab placement for 10 rather than 5 seconds and rotation 360° rather than 180°. Aluminium-shafted, cotton-tipped swabs (Disposable Products, Australia) were introduced horizontally into the nasal cavity 8-10 cm or until resistance was encountered. If the first swab was not tolerated a second swab was performed or nasal secretions were collected from a tissue used to blow the nose [15]. Swabs were placed immediately into skimmed milk glucose glycerol broth and stored at -20°C for transport to the laboratory for storage at -70°C. A 10 μL loop of broth was streaked on bacitracin containing horse blood agar and chocolate agar (Oxoid, Australia). Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Isolation of S. pneumoniae was confirmed by colony morphology, optochin sensitivity and serotyping by the Quellung reaction (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark), H. influenzae by dependence on X and V factors, and M. catarrhalis by colony morphology, Gram stain and oxidase production.

Statistical analysis

Data from 2002 and 2004 were aggregated for analysis of risk factors based on the following criteria: a) carriage prevalence in 2002 and 2004 not significantly different, b) concordant direction of association in univariate analyses, and c) univariate associations showing p ≤ 0.20. Multiple logistic regression was used for risk factor analysis. Adjustment for correlation between individual pairs of observations in the two surveys was made by including participant identity as a clustering variable in logistic models. Effect modification between variables was evaluated.

Given carriage of 40% in Aboriginal mothers in these communities, the primary risk factor for analysis was sex. A 30% prevalence in men was assumed to be clinically significantly different from women. A sample size of 376 males and 376 females was required to detect the difference at the 5% significance level with power of 0.8.

Results

At the time of the 2002 survey, 94% of eligible children had received pneumococcal catch-up vaccination and the mean age at the third dose was 6.7 months (range 4.2 - 13.6). In 2004, all eligible children had received three doses of 7PCV with 33% receiving the third dose greater than 7 months of age. The proportion of participants < 5 years of age, who had received 7PCV in 2002 and 2004, was 30% and 73% respectively. In 2002, 87% of participants ≥15 years had received 23PPV.

A total of 943 specimens were collected from 925 examinations of 551 participants. After exclusions, 905 specimens from 888 examinations of 538 participants remained for analysis (Figure 1). Of all examinations, 60.6% were in adults (> 16 years) and 44.4% were in males. Males comprised a smaller proportion of examinations among adults (Figure 1).

The prevalence of pneumococcal carriage in all examinations was 42.3% (376/888). Carriage prevalence among adults was 28.4% in 2002 and 22.8% in 2004, odds ratio (OR) 0.75 (95% CI, 0.54-1.02). Carriage among children in 2002 was 69.6% and 64.8% in 2004 (OR 0.80; 95% CI, 0.54-1.19). H. influenzae carriage in all examinations was 36.5% (324/888), while carriage prevalence among adults was 24.8% in 2002 and 20.3% in 2004; carriage prevalence in children was 61.3% in 2002 and 52.8% in 2004. M. catarrhalis carriage in all examinations was 39.4% (350/888), 15.7% among adults in 2002 and 19.0% in 2004 with carriage among children of 74.3% in 2002 and 73.0% in 2004 (Table 1).

Pneumococcal carriage was greatest in young children and older age categories (Figure 2). Among adults there was a trend of increasing carriage with increasing age (Table 1). The trend among children was even greater but inverse, pneumococcal carriage decreased greatly with increasing age (Table 1). Carriage of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis showed no pattern over adult age groups but carriage fell with increasing age of children (Figure 2).

Among adults, univariate analyses showed pneumococcal carriage was associated with male sex, chest infection in the previous month, recent runny nose, 1-2 household occupants < 5 years of age, frequency sitting at an outside fire, a young child as the closest personal contact and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis (Table 2). Among children, carriage was associated with recent runny nose, the number of household occupants < 5 years of age, the number of bedroom occupants < 5 years of age, and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis showed independent risk factors (10% significance level) for pneumococcal carriage among adults were: increasing age, male sex, chest infection in the previous month, runny nose in the previous week, frequency of sitting at an outside fire and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis (Table 3). Among children, independent risk factors for carriage were decreasing age, runny nose in the previous week, and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis (Table 3).

There was no effect modification of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis carriage, with risk of pneumococcal carriage, nor effect modification of pneumococcal carriage and carriage of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis.

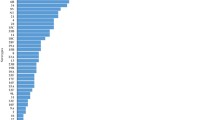

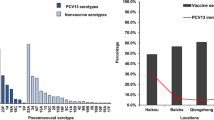

Thirty-nine pneumococcal serotypes were identified. Among adults the predominant types were 6B, 7C, 16F, 19F, and 34 (Figure 3A). Among those < 15 years, serotypes 16F, 1, 11A, 19F, and 6A predominated (Figure 3B), while among those < 5 years, serotypes 16F, 19A, 6B, 1, and 11A predominated (Figure 3C). An epidemic of serotype 1 carriage was evident in 2002 [16]. Serotype 1 carriage was not detected in 2004. Excluding the outbreak of serotype 1, the percentages of serotypes included in the 7, 10, and 13-valent PCV were 23%, 23%, and 29% (adults), 22%, 24%, and 40% (< 15 years), and 26%, 26%, and 40% (< 5 years) respectively. Dominance of serotype 16F, and persistent 19F and 6B carriage (particularly among adults) is noteworthy (Figure 3).

Discussion

This is the first population-based study of respiratory bacterial carriage prevalence and risk factors among Australian Aboriginal adults and older children. Pneumococcal carriage prevalence was 67.4% in children age 2-15 years and 26.0% in adults. The prevalence of H. influenzae carriage was 57.4% in 2-15 year old children and 22.9% in adults. Of the three pathogens, M. catarrhalis was the most prevalent in children (73.7%), and the least prevalent in adults (17.1%). Pneumococcal carriage among adults was associated with increasing age, male sex, recent chest infection, recent rhinorrhoea, frequency of sitting at an outside fire, and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis. Among older children, pneumococcal carriage was strongly associated with younger age and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae or M.catarrhalis and less strongly associated with recent rhinorrhoea. A large number of pneumococcal serotypes circulate in this population. Higher valency PCVs would cover a greater proportion of serotypes in children than adults.

Compared to other population-based studies of pneumococcal carriage, the 42% overall prevalence in this population (mean age 25 years) was midway between that observed among Gambian villagers (65%, median age 15 years) [17] and in a Brazilian slum (36%, median age 16 years) [18] or Kilifi, Kenya (20%, mean age 9 years) [19]. Lower carriage (> 2 years) has been reported in the UK (16%) [20] and Taiwan (10%) [21].

Pneumococcal carriage among children (67%) in this population (mean age 8 years) was comparable to 82% in 5 to 14 year old Gambians [17] and greater than among 5 to 19 year olds in Kilifi (25%), 5 to 17 year old Brazilian slum residents (45%), and Brazilian adolescents (10%) [22]. Pneumococcal carriage among adults in this population (26%) was lower than in Gambia (50%), similar to a Brazilian slum (20%), and greater than in Kilifi (3%), the UK (7%), or Taiwan (0%). An earlier study from Central Australia reported pneumococcal carriage in 34% of a selected group of Aboriginal adults [23]. The differences in prevalence noted above are difficult to explain due to a lack of data on methodology and comparable risk factors.

H. influenzae carriage in children (63%) was greater than that reported in north Indian primary school children (42%, 5-10 years) [24] or Kilifi (22%, 3-9 years) [19]. Carriage of M. catarrhalis (74% children, 17% adults) was greater than that reported in previous studies of healthy children (51%) and adults (5%) in Belgium [25] and hospitalized children (7%, 4-15 years) and adults (1%) in Denmark [26].

The decreasing pneumococcal carriage with increasing age of children has been described in other studies, albeit with varied patterns in different populations [17–21]. Of note, the studies cited here have been conducted in populations before introduction of 7PCV. Carriage prevalence of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis among children also fell with increasing age.

Interestingly, the increased pneumococcal carriage with increasing adult age (38% ≥55 years versus 20% among 16 to 34 year olds) that we observed was not seen in The Gambia or Kilifi. The reason for increased carriage in older adults is not clear. It is unlikely that the trend of increasing pneumococcal carriage is due to chance (test for trend 2002, p = 0.05; 2004, p = 0.003; overall, p = 0.0005). Patterns of social interaction, particularly exposure to children, are usually less intense in older adults but may vary in different settings. Biological (e.g. immunosenescence), environmental (e.g. smoke exposure, stress), and chronic disease factors may also be important.

Odds of pneumococcal carriage were substantially increased if H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis were also detected. The Kilifi study reported a similar magnitude of association between pneumococcal carriage and concurrent carriage of H. influenzae [19]. The association with detection of other pathogens may reflect either facilitation of pneumococcal carriage by H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis, or simply non-species specific risk of nasopharyngeal carriage.

Our data, as well as contemporary [19, 27] and historical [28] studies, describe increased pneumococcal carriage associated with upper respiratory infections. Our data also indicate an association of recent chest infection with increased pneumococcal carriage in adults. Episodes of pneumonia are associated with increased pneumococcal carriage [29, 30].

We found 2.2 times the odds of pneumococcal carriage among adult males compared to females. An association of carriage with gender has not been reported in most studies [17, 19, 27, 28], an exception being one study of adolescents [22]. Some of the factors potentially associated with both gender and carriage, such as contact with children, chronic illness, smoking or sitting at an outside fire, were included in multivariate analyses.

Pneumococcal carriage and respiratory infection have been associated with exposure to air pollution of different types [22, 31]. We found the frequency of sitting at an outside fire increased the risk of pneumococcal carriage. Sitting and cooking at outside fires is common in rural Aboriginal communities. Thus, our data strengthen the growing body of evidence linking smoke exposure to increased risk of respiratory infection.

The large number of pneumococcal carriage serotypes which were detected suggests that pneumococcal transmission is substantial in this population. Our data suggest that the indirect effects of higher valency PCV may be greater than 7PCV (particularly for young infants who acquire S. pneumoniae from their siblings), with a more limited incremental effect among adults.

Our study has a number of limitations. Our sample collection methods underestimate carriage prevalence. Non-probability sampling may have introduced selection bias. Sampling aimed to identify equal numbers of typical adult men and women, with children numbering two thirds that of adults. However, sampling was biased towards adult women, and given lower carriage in women, adult carriage may be underestimated. Analyses of risk factors need to be interpreted in the light of possible sampling bias. Despite non-probability sampling, valid prevalence estimates are likely to fall within the given confidence intervals. Finally, this study is limited to a three year period following the introduction of 7PCV. Although carriage of serotypes 19F and 6B in 2004 remained substantial, it may have fallen in subsequent years. Another carriage study across the NT documented little change in childhood carriage of 19F and 23F between 2003 and 2005 but a reduction in carriage of 6B was observed [32].

The implications for public health relate to the introduction of PCV and prevention of pneumococcal transmission and disease. High overall carriage prevalence indicates a large proportion of the population contributing to pneumococcal transmission, which is consistent with the high rates of IPD observed among Aboriginal adults [7]. Such a reservoir of potentially transmitting individuals may maintain circulation of pneumococcal serotypes after introduction of PCV and limit the magnitude, and increase the time to development, of indirect effects. High rates of bacterial carriage also suggest potential for replacement disease following reduction of VT carriage. Ongoing pneumococcal transmission among Aboriginal adults may explain data showing no reduction in rates of IPD in Aboriginal adults following introduction of 7PCV despite a 30% to 45% reduction in IPD among all Australian adults following 7PCV introduction [33].

Conclusion

Nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumonia, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis is high in this population. These data indicate that frequent exposure to outside fires and prevalent respiratory viral and bacterial infections all play a role in maintaining high rates of pneumococcal carriage. Interventions which reduce smoke exposure may reduce pneumococcal carriage. Among adults, low serotype coverage of higher valency PCV suggests that increased herd protection above that of 7PCV may be limited, although higher coverage among children, particularly during a serotype 1 outbreak, suggests that increased herd protection will be afforded to young infants. Ongoing carriage of 7PCV serotypes 19F and 6B is noteworthy, although our data are limited to a three year period following introduction of 7PCV.

Note

This work was funded by Wyeth Australia, the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia and Menzies School of Health Research. This work was undertaken at Menzies School of Health Research, PO Box 41096, Casuarina, Darwin, NT, Australia. The sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Peter Morris and Amanda Leach have received research funding from Wyeth and GlaxoSmithKline and Peter Morris has acted as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. Grant Mackenzie is now affiliated with the Medical Research Council (UK) The Gambia.

References

O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Delport SD, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, Lee E, Mulholland K, Levine OS, Cherian T: Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009, 374: 893-902. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6.

Shann F, Gratten M, Germer S, Linnemann V, Hazlett D, Payne R: Aetiology of pneumonia in children in Goroka Hospital, Papua New Guinea. Lancet. 1984, 2: 537-541. 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90764-5.

Wall RA, Corrah PT, Mabey DC, Greenwood BM: The etiology of lobar pneumonia in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ. 1986, 64: 553-558.

Kofteridis D, Samonis G, Mantadakis E, Maraki S, Chrysofakis G, Alegakis D, Papadakis J, Gikas A, Bouros D: Lower respiratory tract infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae: clinical features and predictors of outcome. Med Sci Monit. 2009, 15: CR135-CR139.

Murphy TF, Parameswaran GI: Moraxella catarrhalis, a human respiratory tract pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49: 124-131. 10.1086/599375.

Epidemiology Branch, Territory Health Services: Mortality in the Northern Territory 1979-1997. Darwin. Edited by: Dempsey KE, Condon JR. 1999

Krause VL, Reid SJC, Merianos A: Invasive pneumococcal disease in the Northern Territory of Australia, 1994-1998. Med J Aust. 2000, 173: S27-S31.

Sleeman KL, Daniels L, Gardiner M, Griffiths D, Deeks JJ, Dagan R, Gupta S, Moxon ER, Peto TE, Crook DW: Acquisition of Streptococcus pneumoniae and nonspecific morbidity in infants and their families: a cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005, 24: 121-127. 10.1097/01.inf.0000151030.10159.b1.

Syrjanen RK, Auranen KJ, Leino TM, Kilpi TM, Makela PH: Pneumococcal acute otitis media in relation to pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005, 24: 801-806. 10.1097/01.inf.0000178072.83531.4f.

Mbelle N, Huebner RE, Wasas AD, Kimura A, Chang I, Klugman KP: Immunogenicity and impact on nasopharyngeal carriage of a nonavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JID. 1999, 180: 1171-1176. 10.1086/315009.

Obaro SK, Adegbola RA, Chang I, Banya WA, Jaffar S, McAdam KW, Greenwood BM: Safety and immunogenicity of a nonavalent pneumococcal vaccine conjugated to CRM197 administered simultaneously but in a separate syringe with diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccines in Gambian infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000, 19: 463-469. 10.1097/00006454-200005000-00014.

United States Centers for Disease Control: Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease - United States, 1998-2003. MMWR. 2005, 54: 893-897.

Mackenzie G, Carapetis J, Leach AJ, Hare K, Morris P: Indirect effects of childhoodpneumococcal vaccination on pneumococcal carriage among adults and older children in Australian Aborigianl communities. Vaccine. 2007, 25: 2428-2433. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.015.

O'Brien KL, Nohynek H, The WHO Pneumococcal Vaccine Trials Carriage Working Group: Report from a WHO Working Group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003, 22: 133-140.

Leach AJ, Stubbs E, Hare K, Beissbarth J, Morris PS: Comparison of nasal swabs with nose blowing for community-based pneumococcal surveillance of healthy children. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46: 2081-2082. 10.1128/JCM.00048-08.

Smith-Vaughan H, Marsh R, Mackenzie G, Fisher J, Morris PS, Hare K, McCallum G, Binks M, Murphy D, Lum G, Cook H, Krause V, Jacups S, Leach AJ: Age-specific cluster of cases of serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in remote indigenous communities in Australia. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16: 218-221. 10.1128/CVI.00283-08.

Hill PC, Akisanya A, Sankareh K, Cheung YB, Saaka M, Lahai G, Greenwood BM, Adegbola RA: Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Gambian villagers. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 43: 673-679. 10.1086/506941.

Reis JN, Palma T, Ribeiro GS, Pinheiro RM, Ribeiro CT, Cordeiro SM, da Silva Filho HP, Moschioni M, Thompson TA, Spratt B, Riley LW, Barocchi MA, Reis MG, Ko AI: Transmission of Streptococcus pneumoniae in an urban slum community. J Infect. 2008, 57: 204-213. 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.017.

Abdullahi O, Nyiro J, Lewa P, Slack M, Scott JAG: The descriptive epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae nasopharyngeal carriage in children and adults in Kilifi District, Kenya. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008, 27: 59-64. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31814da70c.

Pebody RG, Morgan O, Choi Y, George R, Hussain M, Andrews N: Use of antibiotics and risk factors for carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: a longitudinal household study in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect. 2009, 137: 555-561. 10.1017/S0950268808001143.

Chen C, Huang Y, Su L, Lin T: Nasal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in healthy children and adults in northern Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007, 59: 265-269. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.012.

Cardozo DM, Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Andrade A-LSS, Silvany-Neto AM, Daltro CHC, Brandao M-AS, Brandao AP, Brandileone MC: Prevalence and risk factors for nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae among adolescents. J Med Microbiol. 2008, 57: 185-189. 10.1099/jmm.0.47470-0.

Hansman D, Morris S, Gregory M, McDonald B: Pneumococcal carriage amongst Australian aborigines in Alice Springs, Northern Territory. J Hygiene. 1985, 95: 677-684. 10.1017/S0022172400060782.

Jain A, Kumar P, Awasthi S: High nasopharyngeal carriage of drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae in north Indian schoolchildren. Trop Med Int Health. 2005, 10: 234-239. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01379.x.

Vaneechoutte M, Verschraegen G, Claeys G, Weise B, Vanden Abeele AM: Respiratory tract carrier rates of Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis in adults and children and interpretation of the isolation of M. catarrhalis from sputum. J Clin Microbiol. 1990, 28: 2674-2680.

Ejlertsen T, Thisted E, Ebbesen F, Olesen B, Renneberg J: Branhamella catarrhalis in children and adults. A study of prevalence, time of colonisation, and association with upper and lower respiratory tract infections. J Infect. 1994, 29: 23-31. 10.1016/S0163-4453(94)94979-4.

Regev-Yochay G, Raz M, Dagan R, Porat N, Shainberg B, Pinco E, Keller N, Rubinstein E: Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae by adults and children in community and family settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 38: 632-639. 10.1086/381547.

Brimblecombe FSW, Cruickshank R, Masters PL, Reid DD: Family studies of respiratory infections. BMJ. 1958, 29: 119-128. 10.1136/bmj.1.5063.119.

Dochez AR, Avery OT: Varieties of pneumococcus and their relation to lobar pneumonia. J Exp Med. 1915, 21: 114-132. 10.1084/jem.21.2.114.

Lloyd-Evans N, O'Dempsey TJD, Baldeh I, Secka O, Demba E, Todd JE, McCardle TF, Banya WS, Greenwood BM: Nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci in Gambian children and in their families. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996, 15: 866-871. 10.1097/00006454-199610000-00007.

Smith KR, Samet JM, Romieu I, Bruce N: Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax. 2000, 55: 518-532. 10.1136/thorax.55.6.518.

Leach AJ, Morris PS, McCallum GB, Wilson CA, Stubbs L, Beissbarth J, Jacups S, Hare K, Smith-Vaughan HC: Emerging pneumococcal carriage serotypes in a high-risk population receiving 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine since 2001. BMC Infect Dis. 2009, 9: 121-10.1186/1471-2334-9-121.

Roche PW, Krause V, Cook H, Barralet J, Coleman D, Sweeny A, Fielding J, Giele C, Gilmour R, Holland R, Kampen R, Brown M, Gilbert L, Hogg G, Murphy D: Invasive pneumococcal disease in Australia, 2006. Commun Dis Intell. 2008, 32: 18-30.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/10/304/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Wyeth Australia. The funding body had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. GM was supported by a scholarship from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia. AL and PM were employees of Menzies School of Health Research supported by Fellowships provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council. JC was an employee of the Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne. We thank the participants and communities involved in the study as well as the Tiwi Health Board for their support. Ms Priscilla Tipakalippa was instrumental in the conduct of data collection in the field. Menzies School of Health Research provided essential support for the work. We thank the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health for valuable support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Declaration of competing interests

Peter Morris and Amanda Leach have received research funding from Wyeth Vaccines and GlaxoSmithKline and Peter Morris has acted as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GM conceived of the study, and participated in its design, coordination, data collection, and manuscript preparation. JF participated in coordination of the study, data collection and manuscript preparation. AL, JC, and PM participated in the design of the study and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackenzie, G.A., Leach, A.J., Carapetis, J.R. et al. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carriage of respiratory bacterial pathogens in children and adults: cross-sectional surveys in a population with high rates of pneumococcal disease. BMC Infect Dis 10, 304 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-304

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-304