Abstract

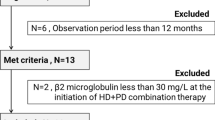

Combined therapy with peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD) represents a treatment option for PD patients who cannot maintain adequate solute and fluid removal. It has rapidly gained popularity in Japan, and 15 years of accumulated experiences is available. Serum creatinine, serum β2 microglobulin (β2m), body weight, and blood pressure decreased, whereas hemoglobin increased after initiating combined therapy. These results indicated that both adequacy of dialysis and hydration status were significantly improved. In addition, dialysate-to-plasma ratio of creatinine (D/P Cr) as obtained from peritoneal equilibration test (PET) was decreased, probably due to the functional and histological improvements of the peritoneal membrane. Combined therapy may have a good impact on the prevention of cardiovascular disease through reduction of blood pressure, correction of fluid overload, and improvement of left ventricular hypertrophy. Quality of life may improve as a result of decreases in uremic symptomatology and freedom from bag exchanges. On the other hand, combined therapy with PD and HD has some concerns. A reduction in urine volume during combined therapy indicates a decline in residual renal function, and may have potential negative impacts on life expectancy. Furthermore, induction of combined therapy would increase the overall duration of PD treatment and susceptibility to peritonitis. We have to pay attention to the development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, as the most serious complication of PD, because both prolonged PD duration and increased number of peritonitis episodes are independent risk factors. Here, we propose criteria for the indication and discontinuation of combined therapy. Under these criteria, Kt/V, serum β2m, and uremic symptoms including nutritional status, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent-hyporesponsive anemia, and restless legs syndrome were used as markers of dialysis adequacy. On the other hand, higher blood pressure, heart enlargement or pleural effusion on chest X-ray, and persistent peripheral edema were used as markers of hydration status. Further studies, particularly prospective cohort studies with a large group of cases, are needed to confirm the clinical efficacy of combined therapy with PD and HD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is recommended as a first-line renal replacement therapy (RRT) for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1]. The main evidence to support this recommendation is that residual renal function (RRF) is better preserved among patients treated with PD than in those undergoing hemodialysis (HD) [2]. The degree of RRF affects not only adequate solute and fluid removal, but also patient survival [3, 4]. However, standard PD is not always sufficient to avoid both the risk of uremic complications of inadequate dialysis and fluid overload, especially once loss of RRF has occurred. Peritoneal permeability is also widely recognized as showing gradual enhancement over time on PD therapy. In Japanese PD patients, the 5-year technique survival rate was estimated as 70 %, and the most common reasons for technique failure are inadequate dialysis and/or ultrafiltration failure [5]. Treatment options for these patients include switching to HD or starting combined therapy with PD and HD, generally in the form of 5–6 days of PD and one HD session per week.

Combined therapy with PD and HD was introduced in Japan in the 1990s, and the first report was written by Watanabe and Kimura [abstract: Watanabe S and Kimura Y et al. Nihon Touseki Igakukai Zasshi. 1993;26 (suppl 1):911]. Kawanishi et al. [6] published the first report in English in 1999, describing 12 patients treated with combined therapy. A PD + HD combination therapy study group was set up in 1996, had met annually and discussed details of the application, mode, and indication of this combination therapy, and issued the first clinical recommendation in 2004 [7]. Since then, combined therapy has rapidly gained popularity in Japan, and as of 2012, approximately 1800 patients (20 % of all PD patients) were estimated to be receiving this therapy [8].

Although several reports have shown the effectiveness and impact of combined therapy with PD and HD, most have been limited by sample size or by being single-center studies [6, 9–20] (Table 1). In these reports, the terminology have not been standardized (i.e., combined therapy, combination therapy, hybrid therapy, complementary dialysis, and bimodal dialysis). We recently reported clinical outcomes for more than 100 patients treated with combination therapy across nine centers in Japan [21]. According to that study, the PD duration prior to switching to combined therapy was approximately 2–4 years and the reason for switching was inadequate dialysis in 25–83 % and fluid overload in 16–42 % (Table 1).

This review summarizes the experience with combined therapy using previous reports, and considers the clinical efficacy of this therapy. We also propose criteria for both initiation and discontinuation of combined therapy.

Criteria for initiation of combined therapy

For the better management of PD, adequate solute and fluid removal are essential and targets have been defined in several guidelines, including the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guideline [22], the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) guideline [23], and the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) guideline [24]. Weekly Kt/V is widely used to assess solute removal, and is determined using the combined renal and peritoneal clearance of urea. The guidelines recommend maintaining weekly Kt/V >1.7. In addition, persistent anorexia, deterioration of nutritional status, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA)-hyporesponsive anemia, and restless legs syndrome could reflect inadequate dialysis even if the target for solute clearance is achieved. Maintenance of euvolemia is also important for the better management of PD patients. Reduction in both ultrafiltration (UF) volume and urinary volume induce volume overload. The presence of peripheral edema, higher or drug-resistant blood pressure, and heart enlargement or pleural effusion on chest X-rays could be signs of fluid overload. Although definitive criteria for the initiation of combined therapy have yet to be established, patients who cannot maintain adequate solute removal and fluid removal are candidates for this therapy.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical and biochemical parameters at the start of combined therapy with PD and HD. Creatinine levels were elevated (12.0–13.5 mg/dL) and urine volume was decreased (150–250 mL/day), whereas weekly Kt/V was maintained at a target level (1.7–2.0) at the start of combined therapy. These results suggest that small solute removal was maintained in many cases, and fluid overload was a considerable reason for the initiation of combined therapy. Indeed, systolic blood pressure was elevated (140–156 mmHg) despite the high UF volume (800–1000 mL/day).

Although the removal of urea nitrogen or creatinine was relatively maintained, β2 microglobulin (β2m) levels were elevated (33–36 mg/L). The level of serum β2m, as a middle-molecule uremic toxin, is known to influence the mortality of HD patients, and is now recognized as a potential guide to the adequacy of dialysis in this population [25]. Since a higher β2m level represented an independent risk factor for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS), the most serious complication of PD [26], β2m level is expected to be a prognostic factor for both PD alone and for combined therapy.

Two reports showed dialysate-to-plasma ratio of creatinine (D/P Cr), obtained from a peritoneal equilibration test (PET), at the start of combined therapy [18, 21]. Increased D/P Cr reflects deterioration in peritoneal function, and increases gradually with duration of PD and cumulative glucose exposure [27]. In addition, D/P Cr is one of the important risk factors for EPS [28]. Since D/P Cr was not elevated, peritoneal deterioration was not clinically evident at the start of combined therapy.

PD patients who cannot maintain adequate solute removal and fluid removal are candidates for combined therapy as described before, and we proposed for criteria for the initiation of combined therapy with PD and HD (Table 3). In these criteria, patients with limited peritoneal capacity and presenting with cardiovascular instability in HD were also candidates for combined therapy even if both solute and fluid removal were maintained [29].

Changes in clinical and biochemical parameters after initiating combined therapy

Table 4 summarizes changes in clinical and biochemical parameters after the initiation of combined therapy. According to these comparative analyses, body weight and blood pressure decreased and hemoglobin increased, and serum creatinine levels decreased despite the decreased urine volume [14, 15, 18, 19, 21]. These results indicated that both the adequacy of dialysis and hydration status were significantly improved. Several studies have demonstrated that hemoglobin levels increased with a reduction in ESA dose, indicated that the elevation in hemoglobin level was due to corrections of both fluid overload and ESA hyporesponsiveness one of the uremic symptoms [15, 18, 19].

Changes in serum β2m varied between reports [16, 18, 21]. Dialysis clearance of β2m with HD using a high-flux membrane is well known to be much higher than with PD [30, 31]. Unlike in PD, serum β2m in patients receiving HD changes dramatically over a week, and we usually measure the highest value at the start of an HD session. Since β2m represents a useful risk factor in PD patients, as previously mentioned, the decline under combined therapy is thought to be a beneficial effect [26].

In most studies, D/P Cr decreased after switching to combined therapy [16, 18, 21]. Several possible explanations for this have been suggested. Firstly, combined therapy could limit further deterioration of the peritoneal membrane by decreasing exposure to glucose and elimination of uremic toxins. In addition to cumulative glucose exposure [32], uremia per se [33] is also associated with structural alternations in the peritoneal membrane. Secondly, peritoneal rest could have a positive impact on peritoneal function. In general, PD was not carried out on the day of a HD session, and almost half of the patients did not undergo PD on another day, defined as a “PD holiday”. Several in vivo [34] and in vitro [35] studies have shown that peritoneal rest reduces the alteration of the mesothelial cells and improves peritoneal function. Thirdly, histological improvement of peritoneal edema secondary to improvement of fluid status might lead to reduction in D/P Cr [36].

Assessment of efficiency of combined therapy

Although small solute removal was obviously improved after switching from PD alone to combined therapy, no standard method has been devised to calculate solute clearances in combined therapy. Kawanishi et al. [14, 16, 29] used equivalent renal clearance (EKR) of urea as proposed by Casino et al. [37], and both total Kt/V and total weekly creatinine clearance (Ccr) were increased in patients after starting combined therapy. The JSDT guideline [24] recommends that the adequacy of dialysis should be determined using the concept of body fluid clear space in combined therapy [24, 31].

Combined therapy and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is one of the most serious complications in dialysis patients, and is responsible for 33.5 % of deaths among Japanese dialysis patients [8]. Since both inadequate dialysis and fluid overload are risk factors, initiating combined therapy may have a positive impact. Although no reports have clarified the effect of combined therapy on the incidence of cardiovascular disease, changes in surrogate markers have been reported. Tanaka et al. [19] found that left ventricular mass index (LVMI) on echocardiography, a well-known risk factor for atherosclerosis, was significantly reduced at 9 months after switching therapy. They also reported that systolic blood pressure was significantly decreased despite prescription of the same dose of antihypertensive medication. Hypertension is a risk factor for mortality, and control of blood pressure by antihypertensive medication reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates in HD [38]. Several other reports have indicated the corrective action on blood pressure, with a reduction in number of antihypertensive drugs [15, 18]. Interestingly, Matsuo et al. [39] recently reported that the cumulative hazard ratio for death was not lower for combined therapy than for HD or PD alone. These results suggest that switching from PD alone to combined therapy may have a good clinical impact on the prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Combined therapy and quality of life

Along with reducing mortality and morbidity, maintaining high quality of life (QOL) is also important for the management of dialysis patients. A meta-analysis by Wyld et al. [40] reported that PD resulted in a clinically higher QOL than HD, however, but the difference was not statistically significant. Hashimoto et al. [9] found that QOL was improved among six patients switching from PD alone to combined therapy. They concluded that the improvements in QOL may have resulted from decreases in uremic symptomatology and freedom from bag exchanges.

Criteria for discontinuation of combined therapy and prevention of EPS

Combined therapy with PD and HD has some concerns. Urine volume decreases during combined therapy. Since many reports have shown an association between lower RRF and higher mortality among PD patients [3, 4], a decline in RRF by combined therapy might require attention. Further study will be needed to clarify the association between renal volume and outcome among patients receiving combined therapy. Furthermore, induction of combined therapy would increase the overall duration of PD treatment and susceptibility to peritonitis. Both prolonged PD duration and increased number of peritonitis episodes are well known as independent risk factors for EPS [28], and Yamamoto et al. [41] reported that the cut-off points for these parameters are 115.2 months and two times, respectively.

In addition to the absence of criteria for initiation, criteria for discontinuation of combined therapy have also not yet been established. For those patients receiving combined therapy who cannot maintain adequate solute removal and fluid removal, we have to consider discontinuation of combined therapy and switching to other mode of RRT, especially HD thrice weekly. We also proposed criteria for discontinuation of combined therapy PD and HD (Table 5), determined based on the criteria for conventional PD and consideration of the prevention of EPS development as well as impaired solute and fluid removal was an important issue [24]. It is to be noted that conventional solution was used in the most of previous studies. It is well known that neutral-pH, low-glucose degradation products solutions potentially influence the integrity of the peritoneal membrane [42]. Indeed, Yohanna et al. found that the use of these new solutions resulted in better preservation of RRF and greater urine volumes in systematic review [43]. In the future, the reconsideration of criteria for discontinuation will be needed.

Experience of combined therapy in Western countries

Most reports of combined therapy were from Japan, and limited experiences have been reported from the USA [12] and UK [13]. Agarwal et al. [12] observed an improvement in the clinical symptoms for which combined therapy was initiated in 31 patients. McIntyre et al. [13] conducted a prospective study of combined therapy, referred to as bimodal dialysis, in eight incident patients reaching ESRD, and found that RRF was controlled and both blood pressure and LVMI were reduced.

Conclusions

According to the previous reports, both inadequate dialysis and fluid overload were significantly improved by switching from PD alone to combined therapy with PD and HD. In addition, combined therapy has potential effects on improved QOL and correction of peritoneal deterioration. However, the clinical outcomes including mortality, morbidity, and the incidence of EPS remain unknown. Furthermore, criteria for both initiation and discontinuation of combined therapy have not been established. To solve these clinical questions, we are now undertaking a prospective cohort study.

Abbreviations

- Ccr:

-

creatinine clearance

- D/P Cr:

-

dialysate-to-plasma ratio of creatinine

- EKR:

-

equivalent renal clearance

- EPS:

-

encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis

- ESA:

-

erythropoiesis-stimulating agent

- ESRD:

-

end-stage renal disease

- HD:

-

hemodialysis

- ISPD:

-

International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis

- JSDT:

-

Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy

- KDOQI:

-

Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative

- LVMI:

-

left ventricular mass index

- PD:

-

peritoneal dialysis

- PET:

-

peritoneal equilibration test

- QOL:

-

quality of life

- RRF:

-

residual renal function

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy

- UF:

-

ultrafiltration

- β2m:

-

β2 microglobulin

References

Chaudhary K, Sangha H, Khanna R. Peritoneal dialysis first: rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):447–56.

Jansen MA, Hart AA, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, et al. Predictors of the rate of decline of residual renal function in incident dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62(3):1046–53. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00505.x.

Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(10):2158–62.

Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, Correa-Rotter R, Ramos A, Moran J, et al. Effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(5):1307–20.

Nakamoto H, Kawaguchi Y, Suzuki H. Is technique survival on peritoneal dialysis better in Japan? Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(2):136–43.

Kawanishi H, Moriishi M, Katsutani S, Sakikubo E, Tsuchiya S. Hemodialysis together with peritoneal dialysis is one of the simplest ways to maintain adequacy in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 1999;15:127–31.

Fukui H, Hara S, Hashimoto Y, Horiuchi T, Ikezoe M, Itami N, et al. Review of combination of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis as a modality of treatment for end-stage renal disease. Ther Apher Dial. 2004;8(1):56–61.

Nakai S, Hanafusa N, Masakane I, Taniguchi M, Hamano T, Shoji T, et al. An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2012). Ther Apher Dial. 2014;18(6):535–602. doi:10.1111/1744-9987.12281.

Hashimoto Y, Matsubara T. Combined peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis therapy improves quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients. Adv Perit Dial. 2000;16:108–12.

Kawanishi H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Five years’ experience of combination therapy: peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2002;18:62–7.

Kanno Y, Suzuki H, Nakamoto H, Okada H, Sugahara S. Once-weekly hemodialysis helps continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients who have insufficient solute removal. Adv Perit Dial. 2003;19:143–7.

Agarwal M, Clinard P, Burkart JM. Combined peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: our experience compared to others. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23(2):157–61.

McIntyre CW. Bimodal dialysis: an integrated approach to renal replacement therapy. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(6):547–53.

Kawanishi H, Hashimoto Y, Nakamoto H, Nakayama M, Tranaeus A. Combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(2):150–4.

Hoshi H, Nakamoto H, Kanno Y, Takane H, Ikeda N, Sugahara S, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with a combination of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2006;22:136–40.

Kawanishi H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Evaluation of dialysis dose during combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2007;23:135–9.

Moriishi M, Kawanishi H, Tsuchiya S. Impact of combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis on peritoneal function. Adv Perit Dial. 2010;26:67–70.

Matsuo N, Yokoyama K, Maruyama Y, Ueda Y, Yoshida H, Tanno Y, et al. Clinical impact of a combined therapy of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(3):209–16.

Tanaka M, Mise N, Nakajima H, Uchida L, Ishimoto Y, Kotera N, et al. Effects of combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis on left ventricular hypertrophy. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31(5):598–600. doi:10.3747/pdi.2010.00273.

Suzuki H, Hoshi H, Inoue T, Kikuta T, Tsuda M, Takenaka T. Combination therapy with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;177:71–83.

Maruyama Y, Yokoyama K, Nakayama M, Higuchi C, Sanaka T, Tanaka Y, et al. Combined therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: a multicenter retrospective observational cohort study in Japan. Blood Purif. 2014;38(2):149–53. doi:10.1159/000368389.

Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy Work G. Clinical practice guidelines for peritoneal dialysis adequacy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S98–129. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.006.

Lo WK, Bargman JM, Burkart J, Krediet RT, Pollock C, Kawanishi H, et al. Guideline on targets for solute and fluid removal in adult patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(5):520–2.

Working Group Committee for Preparation of Guidelines for Peritoneal Dialysis JSfDT, Japanese Society for Dialysis T. 2009 Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy guidelines for peritoneal dialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2010;14(6):489–504. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00901.x.

Cheung AK, Rocco MV, Yan G, Leypoldt JK, Levin NW, Greene T, et al. Serum beta-2 microglobulin levels predict mortality in dialysis patients: results of the HEMO study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(2):546–55.

Yokoyama K, Yoshida H, Matsuo N, Maruyama Y, Kawamura Y, Yamamoto R, et al. Serum beta2 microglobulin (beta2MG) level is a potential predictor for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2008;69(2):121–6.

Davies SJ, Phillips L, Naish PF, Russell GI. Peritoneal glucose exposure and changes in membrane solute transport with time on peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(5):1046–51.

Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, Nakayama M, Miyazaki M, Nakamoto H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 4:S83–95.

Kawanishi H, Moriishi M. Clinical effects of combined therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27 Suppl 2:S126–9.

Evenepoel P, Bammens B, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Superior dialytic clearance of beta(2)-microglobulin and p-cresol by high-flux hemodialysis as compared to peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2006;70(4):794–9.

Yamashita AC. A kinetic model for peritoneal dialysis and its application for complementary dialysis therapy. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;177:3–12.

Witowski J, Jorres A, Korybalska K, Ksiazek K, Wisniewska-Elnur J, Bender TO, et al. Glucose degradation products in peritoneal dialysis fluids: do they harm? Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;84:S148–51.

Williams JD, Craig KJ, Topley N, Von Ruhland C, Fallon M, Newman GR, et al. Morphologic changes in the peritoneal membrane of patients with renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(2):470–9.

Zareie M, Keuning ED, ter Wee PM, Beelen RH, van den Born J. Peritoneal dialysis fluid-induced changes of the peritoneal membrane are reversible after peritoneal rest in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(1):189–93.

Tomo T, Okabe E, Matsuyama K, Iwashita T, Yufu K, Nasu M. The effect of peritoneal rest in combination therapy of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: using the cultured human peritoneal mesothelial cell model. J Artif Organs. 2005;8(2):125–9.

Konings CJ, Kooman JP, Schonck M, Struijk DG, Gladziwa U, Hoorntje SJ, et al. Fluid status in CAPD patients is related to peritoneal transport and residual renal function: evidence from a longitudinal study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(4):797–803.

Casino FG, Lopez T. The equivalent renal urea clearance: a new parameter to assess dialysis dose. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(8):1574–81.

Heerspink HJ, Ninomiya T, Zoungas S, de Zeeuw D, Grobbee DE, Jardine MJ, et al. Effect of lowering blood pressure on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients on dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9668):1009–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60212-9.

Matsuo N, Yokoyama K, Tanno Y, Yamamoto I, Yokoo T. Combined therapy using peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis may increase the indications for peritoneal dialysis in the United States. Kidney Int. 2015;87(6):1259–60. doi:10.1038/ki.2015.56.

Wyld M, Morton RL, Hayen A, Howard K, Webster AC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9):e1001307. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307.

Yamamoto R, Otsuka Y, Nakayama M, Maruyama Y, Katoh N, Ikeda M, et al. Risk factors for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in patients who have experienced peritoneal dialysis treatment. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9(2):148–52.

Pletinck A, Vanholder R, Veys N, Van Biesen W. Protecting the peritoneal membrane: factors beyond peritoneal dialysis solutions. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):542–50. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2012.144.

Yohanna S, Alkatheeri AM, Brimble SK, McCormick B, Iansavitchous A, Blake PG, et al. Effect of neutral-pH, low-glucose degradation product peritoneal dialysis solutions on residual renal function, urine volume, and ultrafiltration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(8):1380–8. doi:10.2215/CJN.05410514.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Y.M. drafted the manuscript. K.Y. helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruyama, Y., Yokoyama, K. Clinical efficacy of combined therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Ren Replace Ther 2, 11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-016-0023-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-016-0023-5