Abstract

Background

This review discusses the findings from epidemiological studies that have examined the possible role of meat and colorectal cancer (CRC) risk in Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries.

Methods

We conducted a literature search in the PubMed, Clinical Trials, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and Cochrane databases for observational studies that investigated the association between meat and CRC risk in adults from the MENA region.

Results

Eleven studies were included in this review. For red meat overall, significant associations were found. Regarding beef meat intake, the study included found controversial results with OR = 0.18 (95% CI 0.03–0.09). A positive association was observed between chicken and CRC risk, at OR = 2.52 (95% CI 1.33–4.77) to OR = 4.00 (95% CI 1.53–10.41) to OR = 15.32 (95% CI 3.28–71.45). A significant association was observed between processed meat intake and CRC risk, OR = 9.08 (95% CI 1.02–80.58).

Conclusion

This is the first literature review which illustrated the association between meat consumption and CRC risk in MENA region. We concluded that these studies included in this review have been controversial and not sufficient to establish a clear relationship between CRC and meat consumption in the MENA region. Further studies are necessary to be carried out in this region, with a larger sample size and submit to rigorous criteria. This review will help researchers to improve the quality of future studies about the association between CRC and nutritional diet in general and meat in particular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death and the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide. In 2018, there were approximately 2 million new cases and 1 million deaths worldwide [1]. The incidence of CRC is higher in the developed countries compared with the developing countries [1]. Several studies have shown that there is a strong relationship between diet and the development of CRC [2, 3]. A large number of epidemiological studies have found a positive association between high intake of red meat and processed meat and CRC [4, 5]. In contrast, other studies have shown that there is no correlation between meat consumption and CRC risk [6]. Overall, most of these epidemiological studies have been conducted in developed countries, whose citizens adopt a Western diet rich in fat [7, 8]. In the other hand, a little information about this relationship in Middle Eastern and North African countries (MENA) is available. As compared to Western countries, the incidence of CRC in the MENA region is low, but it seems to have increased significantly during the last decade [9]. Moreover, the traditional diet in the MENA region is known to be healthy. This diet is characterized by a higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and lower to moderate in the consumption of meats and in the consumption of alcohol [10]. However, people from the MENA region are changing their traditional diet. A big part of this change is attributed to the globalization with the invasion of Western food rich in meat to the MENA countries [11]. In addition, this area has a many traditional foods of animal origin which, are widely consumed such as Gueddid, Pastirma, Khlii, Sujuk, Merguez, Tehal, Kourdass, and Nakanek [12, 13]. Moreover, they are mainly prepared at the household level under poor sanitary conditions [12]. The increase of CRC in this region probably is related to change of their traditional diet, in addition to these traditional meat products.

Consequently, the present review aimed at describing the associations between meat and CRC in Middle Eastern and North African countries.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted an exhaustive search for full-text articles in databases: Pub Med, Clinical Trials, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and Cochrane databases, following the PRISMA guidelines [14], complemented by scrutinizing guidelines, databases, and references of identified publications. Search terms included fresh OR processed red meat OR white meat in combination with colon cancer OR rectal cancer OR colorectal cancer in MENA countries and by putting the combination of all these keywords. Red meat is mostly considered to be derived from mammals: beef, lamb, goat, veal, camel, pork, and rabbit. White meat is mostly derived from poultry, chicken, and turkey [15]. Processed meat is meat preserved by smoking, curing salting, or by the addition of chemical preservatives [16] used for a cooking method such as “steamed, grilled, tajine, roasted” types. MENA countries include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. All identified studies published until 31 October 2018 were considered.

Eligibility criteria

The studies that were included in this review were original studies conducted among people living in the MENA region. All observational studies “prospective and retrospective” were held eligible for inclusion, only ecological and experimental studies were excluded. The studies that investigated the associations between meat consumption and CRC and provided estimates of the associations, by reporting the odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were included. All the reviewed articles had been published in English or French.

Quality assessment

Articles were selected independently by two investigators. Relevant publications were selected first upon reading of the title and abstract, and by reading the full text of the chosen articles. Several confounding factors (such as age, sex, tobacco and alcohol consumption) were considered in the selection procedure to ensure the questions validity. In addition, we determined the evidence level of all studies included in this review (Table 1).

Results

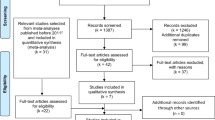

The number of studies found until 31 October 2018 was 84. Among them, 72 papers were excluded (13 papers duplicates, 46 papers were conducted outside of the MENA region (Fig. 1) and 6 papers did not study the relation between meat intake and CRC risk and 8 papers did not precise the risk) [17, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (Table 2). Upon excluding the studies which did not meet the criteria (for the most part experimental studies), only eleven studies were singled out for reviewing (Fig. 1). The included studies represent six countries: Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Tunisia. The methodological characteristics, the inclusion criteria of patients and the main exposures including the consumption of all types of meat and CRC risk have been summarized in (Table 3) as well as the strength of the findings represented by the study design (level evidence) [42], the methodological weaknesses, the biases, and the limitations of each study. The study results are summarized in Table 3 and described in the text.

Regarding red meat consumption, a positive association was observed with CRC risk in five case-controls studies, Jordan case-control studies conducted by Arafa et al. [21], two Iran case-control studies conducted by Safari et al. and Azizi et al. [22, 26], and Egypt [23] and Saudi Arabia [18], respectively (OR = 2.66, 95% CI 1.83–3.88; OR = 2.616, 95% CI = 1.361–5.030; OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.05–2.19; OR = 57.1 95% CI 12.1–270.3; OR = 13.5, 95% CI 2.64–68.84). Conversely, the case-control study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Nashar and Almurshed [18] has found an inverse association between beef meat intake and CRC risk with (OR = 0.18, 95% CI 0.03–0.90), whereas Abu Mweis et al. [24] from Jordan and Bener et al. from Qatar [19] have found no significant association between red meat intake and CRC risk, respectively (OR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.37–1.11; OR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.77–1.87).

Concerning the relation between processed meat and CRC risk, the three studies, from Egypt [23, 28], Tunisia [20], and Jordan [27], showed a positive association (OR = 2.4, 95% CI 1.5–3.8; OR = 5.12, 95% CI = 3.08–8.53; OR = 5.1, 95% CI 1.4–18.5; and OR = 9.08, 95% CI = 1.02–80.58, respectively).

For chicken, Nashar and Almurshed from Saudi Arabia [18] and Abu Mweis et al. [24] and Tayyem et al. from Jordan [27] showed a significant association between its consumption and CRC risk (OR = 4, 95% CI 1.53–10.41; OR = 2.52, 95% CI 1.33–4.77; and OR = 15.32, 95% CI = 3.28–71.45, respectively).

Regarding to the relation between saturated fat and CRC risk, the two Jordanian studies conducted by Arafa et al. and Tayyem et al. [21, 25] showed the significant association (OR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05, OR = 5.23, 95% CI 2.33–11.76 respectively).

Finally, no studies have examined the relationship between traditional meat products in the MENA region and CRC risk.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to describe the associations between meat and CRC risk in MENA countries. The results of this review showed that there were few studies conducted in this region, they did not cover all countries and did not include all types of meat, particularly traditional meat products.

All included studies have a low evidence level and results were not usually homogeneous. The relationship obtained between meat intake and CRC risk varies from one country to another, as it sometimes may vary in the same country. For instance, the case-control study conducted in Jordan by Arafa et al. [21] found a positive association between red meat intake and CRC risk, while another case-control study conducted by Abu Mweis et al. [24] in the same country reported no significant association. Another example is the case-control study conducted in Saudi Arabia [18] which showed a decreasing risk of CRC for beef meat consumption, while the case-control study conducted in Qatar [19] showed no significant associations between all types of meat and CRC risk.

Some results from this literature review [18, 21, 23, 24] were similar to those reported in a meta-analysis involving 19 prospective studies [43] and a large Japanese cohort study [44] and a large European cohort study EPIC [45]. Moreover, the result from the Jordanian study [24], which exhibited no significant association between red meat intake and CRC risk, was in agreement with a large meta-analysis [46]. On the other hand, some results were completely controversial between findings in this literature review and others outside MENA region studies. This was the case for three case-control studies [18, 19, 24] which reported a positive association between chicken intake and CRC risk. However, the results from a meta-analysis, which included 16 case-control studies and 5 cohort studies were completely controversial [47].

Furthermore, the study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Nashar and Almurshed [18] showed a positive association between lamb meat and CRC risk, and a negative association between beef meat and CRC risk, whereas a meta-analysis including 19 prospective cohort studies and comprising data from 15,183 CRC patients [48] found a positive association between beef and lamb consumption and CRC risk. In addition, a large cohort study conducted in Denmark and included 644 cases of colon cancer and 345 cases of rectal cancer found a positive association between lamb meat and colon cancer [49]. In fact, the beef consumption has a higher heme iron content (mean heme iron in cooked beef 2.63 ± 0.5 mg/100 g) compared to lamb consumption (mean heme iron in cooked lamb 1.68 ± 0.4 mg/100 g). One of the main hypotheses explaining the link between heme iron and CRC development is based on red meat pro-oxidative properties that could induce the oxidation of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids [50]. Oxidation leads to the formation of lipid peroxidation and advanced glycation end-products, such as malondialdehyde or 4-hydroxynonenal, which are cytotoxic and genotoxic [50]. In addition, most of epidemiologic and experimental evidence support a major role of heme iron (abundant in red meat but far less in poultry), in the promotion of CRC risk especially by the consumption of red and processed meat [51].

Hence, we noted that the results found in Saudi Arabia by Nashar and Almurshed [18] about the relationship between beef consumption and CRC risk remain less logical than those found in the scientific research.

Finally, the studies included in this literature review have a number of limitations. All these studies have a low evidence level and took a small sample size, which is not representative of the target population. The included studies had a retrospective nature (case-control studies) and some limitations were presented in those retrospective studies such as biases related to memory, seasonal variations in fruits, vegetables, and plates and cooking techniques. Furthermore, the majority of studies did not exclude the participants that followed a diet such as diabetic and hypertensive patients and did not include the recently diagnosed patients (new cases), which may affect the quality of the collecting dietary data. The majority of studies used the FFQ (Food Frequency Questionnaire) which is susceptible to errors and choose one year to dietary recall time, which may not be sufficient to determine associations with a disease state that take years to be developed. On the other hand, some of studies did not adjust the consumption of meat with others exposure to determine the confounding factors such as body mass index, physical activity, and energy intake. This could perhaps explain such controversial results. Furthermore, most of case-control studies did not specify red meat types consumed; they reported only red meat consumption. In addition, most of case-control studies did not consider cooking methods for meat and its doneness levels.

The major strongest point of this review is that it is the first to summarize and evaluate the association of meat consumption and CRC risk in the MENA region. The main results were heterogeneous, not always the same as in the other countries and sometimes completely controversial. These findings have several limitations linked mainly to the design of the included studies which are susceptible to different forms of biases such as random error, misclassification, and confounding [52].

Conclusion

These results are not only insufficient, but also unconvincing. Furthermore, no studies have worked on the traditional meat products in the MENA region, which may explain partly the increase of CRC risk in this region. Further studies are necessary to be carried out in this region, with a larger sample size and conducted in rigorous criteria. These findings will help researchers to improve the quality of future studies about the association between CRC risk and nutritional diet in general.

Availability of data and materials

All data available if you need you will contact the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- MENA:

-

Middle Eastern and North African

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

References

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14:89–103.

Angelo SN, Lourenço GJ, Magro DO, Nascimento H, Oliveira RA, Leal RF, et al. Dietary risk factors for colorectal cancer in Brazil: a case control study. Nutr J. 2016;15:20.

Grimmett C, Simon A, Lawson V, Wardle J. Diet and physical activity intervention in colorectal cancer survivors: a feasibility study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:1–6.

Potera C. Red meat and colorectal cancer: exploring the potential HCA connection. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:A189.

Hastert TA, White E. Association between meeting the WCRF/AICR cancer prevention recommendations and colorectal cancer incidence: results from the VITAL cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:1347–59.

Parr CL, Hjartåker A, Lund E, Veierød MB. Meat intake, cooking methods and risk of proximal colon, distal colon and rectal cancer: the Norwegian Women and Cancer (NOWAC) cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1153–63.

Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, Czernichow S, Parr CL, Woodward M. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:171–80.

Durko L, Malecka-Panas E. Lifestyle modifications and colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2014;10:45–54.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86.

La Vecchia C, Bosetti C. Diet and cancer risk in Mediterranean countries: open issues. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:1077–82.

Fahed AC, El-Hage-Sleiman A-KM, Farhat TI, Nemer GM. Diet, genetics, and disease: a focus on the Middle East and North Africa region. J Nutr Metabol. 2012 [cited 2020 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jnme/2012/109037/.

Benkerroum N. Traditional fermented foods of North African countries: technology and food safety challenges with regard to microbiological risks. Comprehen Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2013;12:54–89.

Gagaoua M, Boudechicha H-R. Ethnic meat products of the North African and Mediterranean countries: an overview. J Ethnic Foods. 2018;5:83–98.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9 W64.

De Smet S, Vossen E. Meat: The balance between nutrition and health. A review. Meat Sci. 2016;120:145–56.

World Cancer Research Fund. Changes since the 2007 Second Expert Report. 2018. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/changes-since-2007-second-expert-report.

Rennert G. Prevention and early detection of colorectal cancer--new horizons. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2007;174:179–87.

Nashar RM, Almurshed KS. Colorectal cancer: a case control study of dietary factors, king faisal specialist hospital and researh center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2008;15:57–64.

Bener A, Moore MA, Ali R, El Ayoubi HR. Impacts of family history and lifestyle habits on colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study in Qatar. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:963–8.

Guesmi F, Zoghlami A, Sghaiier D, Nouira R, Dziri C. Alimentary factors predisposing to colorectal cancer risk: a prospective epidemiologic study. Tunis Med. 2010;88:184–9.

Arafa MA, Waly MI, Jriesat S, Al Khafajei A, Sallam S. Dietary and lifestyle characteristics of colorectal cancer in Jordan: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1931–6.

Safari A, Shariff ZM, Kandiah M, Rashidkhani B, Fereidooni F. Dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer in Tehran Province: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:222.

Mahfouz EM, Sadek RR, Abdel-Latief WM, Mosallem FA-H, Hassan EE. The role of dietary and lifestyle factors in the development of colorectal cancer: case control study in Minia, Egypt. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22:215–22.

Abu Mweis SS, Tayyem RF, Shehadah I, Bawadi HA, Agraib LM, Bani-Hani KE, et al. Food groups and the risk of colorectal cancer: results from a Jordanian case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24:313–20.

Tayyem RF, Bawadi HA, Shehadah IN, Abu-Mweis SS, Agraib LM, Bani-Hani KE, et al. Macro- and micronutrients consumption and the risk for colorectal cancer among Jordanians. Nutrients. 2015;7:1769–86.

Azizi H, Asadollahi K, Davtalab Esmaeili E, Mirzapoor M. Iranian dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5:72–80.

Tayyem RF, Bawadi HA, Shehadah I, AbuMweis SS, Agraib LM, Al-Jaberi T, et al. Meats, milk and fat consumption in colorectal cancer. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:746–56.

El-Moselhy EA, Hassan AM, El-Tiby DM, Abdel-Wahed A, Mohammed A-ES, El-Aziz AA. Colorectal cancer in Egypt: clinical, life-style, and socio-demographic risk factors. 2017;15.

Al-Azri M, Al-Kindi J, Al-Harthi T, Al-Dahri M, Panchatcharam SM, Al-Maniri A. Awareness of stomach and colorectal cancer risk factors, symptoms and time taken to seek medical help among public attending primary care setting in Muscat Governorate, Oman. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34:423–34.

Ilgaz AE, Gözüm S. Determination of colorectal cancer risk levels, colorectal cancer screening rates, and factors affecting screening participation of individuals working in agriculture in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:E46–54.

Karimi S, Abdi A, Khatony A, Akbari M, Faraji A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer and the risk factors in Kermanshah Province-Iran 2009-2014. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2019;50:740–3.

Azzeh FS, Alshammari EM, Alazzeh AY, Jazar AS, Dabbour IR, El-Taani HA, et al. Healthy dietary patterns decrease the risk of colorectal cancer in the Mecca Region, Saudi Arabia: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:607.

Mhaidat NM, Al-Husein BA, Alzoubi KH, Hatamleh DI, Khader Y, Matalqah S, et al. Knowledge and awareness of colorectal cancer early warning signs and risk factors among university students in Jordan. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33:448–56.

Nasaif HA, Qallaf SMA. Knowledge of colorectal cancer symptoms and risk factors in the Kingdom of Bahrain: a cross-sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:2299–304.

Tayyem RF, Shehadeh IN, Abumweis SS, Bawadi HA, Hammad SS, Bani-Hani KE, et al. Physical inactivity, water intake and constipation as risk factors for colorectal cancer among adults in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5207–12.

Ghahremani R, Yavari P, Khodakarim S, Etemad K, Khosravi A, Ramezani Daryasari R, et al. The estimated survival rates for colorectal cancer and related factors in iran from 1384 to 1388 using the Aalen’s Additive Risk Model. Iran J Epidemiol. 2016;11:20–9.

Chenni FZ, Taché S, Naud N, Guéraud F, Hobbs DA, Kunhle GGC, et al. Heme-induced biomarkers associated with red meat promotion of colon cancer are not modulated by the intake of nitrite. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:227–33.

Aykan NF, Yalçın S, Turhal NS, Özdoğan M, Demir G, Özkan M, et al. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer in Turkey: a cross-sectional disease registry study (A Turkish Oncology Group trial). Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:145–53.

Rohani-Rasaf M, Abdollahi M, Jazayeri S, Kalantari N, Asadi-Lari M. Correlation of cancer incidence with diet, smoking and socio-economic position across 22 districts of Tehran in 2008. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1669–76.

Almurshed KS. Colorectal cancer: case-control study of sociodemographic, lifestyle and anthropometric parameters in Riyadh. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:817–26.

Omran S, Barakat H, Muliira JK, McMillan S. Dietary and lifestyle risk factors for colorectal cancer in apparently healthy adults in Jordanian hospitals. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32:447–53.

Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1989;95:2S–4S.

Larsson SC, Wolk A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2657–64.

Takachi R, Tsubono Y, Baba K, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Iwasaki M, et al. Red meat intake may increase the risk of colon cancer in Japanese, a population with relatively low red meat consumption. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20:603–12.

Norat T, Bingham S, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Mazuir M, et al. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:906–16.

Brink M, Weijenberg MP, de Goeij AFPM, Roemen GMJM, Lentjes MHFM, de Bruïne AP, et al. Meat consumption and K-ras mutations in sporadic colon and rectal cancer in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1310–20.

Xu B, Sun J, Sun Y, Huang L, Tang Y, Yuan Y. No evidence of decreased risk of colorectal adenomas with white meat, poultry, and fish intake: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:215–22.

Carr PR, Walter V, Brenner H, Hoffmeister M. Meat subtypes and their association with colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:293–302.

Egeberg R, Olsen A, Christensen J, Halkjær J, Jakobsen MU, Overvad K, et al. Associations between red meat and risks for colon and rectal cancer depend on the type of red meat consumed. J Nutr. 2013;143:464–72.

Bastide NM, Chenni F, Audebert M, Santarelli RL, Taché S, Naud N, et al. A central role for heme iron in colon carcinogenesis associated with red meat intake. Cancer Res. 2015;75:870–9.

Bastide N, Pierre F, Corpet D. Heme iron from meat and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis and a review of the mechanisms involved. - PubMed - NCBI. 2011 [cited 2018 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21209396.

Austin H, Hill HA, Flanders WD, Greenberg RS. Limitations in the application of case-control methodology. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:65–76.

Acknowledgements

I thank infinitely Dr. Vanessa Garcia Larsen, Ph.D., Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, for their help in the revision of the manuscript and their great effort during the drafting.

I thank Dr. Taleb Bilal Assistant Professor English Language and Literature General Education at Khawarizmi International College Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, for their help in the revision of the manuscript language.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have rigorously contributed to the study protocol, data collection and analysis, and writing and revision of the article. All approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not required for this review.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mint Sidi Deoula, M., El Kinany, K., Hatime, Z. et al. Meat and colorectal cancer in Middle Eastern and North African countries: update of literature review. Public Health Rev 41, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00127-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00127-4