Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of a botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) injection in the masseter muscle using electromyography (EMG) in an animal model.

Methods

Ten male adult (>3 months of age) New Zealand white rabbits were used. Muscle activity was continuously recorded from 8 hours before to 8 hours after BTX-A injection. The rabbits received unilateral BTX-A injections of either 5 units (group 1, n = 5) or 20 units (group 2, n = 5).

Results

The masseter muscle activity of the rabbits was significantly reduced immediately after BTX-A injection (P < 0.05 for both groups). When the results from group 1 were compared with those from group 2, only the peak voltage was significantly decreased in group 2 (P = 0.013).

Conclusion

Masseter muscle activity measured by EMG was immediately decreased after a BTX-A injection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The abnormal contracture of skeletal muscle often causes pathologic problems. In the oral and maxillofacial areas, abnormal muscle action may cause temporomandibular disorder (TMD) [1], postoperative relapse after orthognathic surgery [2], and open-bite after trauma [3]. To treat TMD, muscle relaxants have been frequently prescribed [4]. To prevent postoperative relapse, muscles around the mandible are surgically stripped [5]. For the correction of open-bite, intermaxillary fixation and adaptation is commonly implemented [6]. However, the therapeutic efficacy of these treatments is not always predictable [6]. In addition, the effects of these treatments cannot be confirmed immediately after treatment initiation.

When Botulinum toxin (BTX) A is injected into masticatory muscles, it immediately causes temporary muscle paralysis, weakness and atrophy due to its pharmacological properties [7]. BTX is a biological exotoxin produced by the gram-positive anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum. BTX causes local muscle paralysis and a reduction in overall contraction power by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine at cholinergic motor nerve terminals [8]. The bacterium produces seven serologically distinct BTXs that are potent neuroparalytic agents and are designated A-G [9]. Administration of Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) is considered to be safe by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [10], although some adverse side effects, such as systemic weakness, have been reported [11]. BTX-A has been successfully applied to various anatomical areas, especially the oral and maxillofacial regions. BTX-A is used to treat sialorrhoea, TMD, bruxism, focal dystonia, muscle spasm, and muscle hypertrophy [12-16]. In addition, the injection of BTX-A into the digastric muscle corrected post-operative anterior open bite [17]. However, there have been few animal studies about the effects of BTX on the masticatory muscle.

Electromyography (EMG) has been used extensively for diagnostic purposes, such as facial muscle localization before BTX-A injection [18-20]. However, few studies have used EMG to ascertain the effects of BTX injection on targeted muscles. This lack of information concerning muscle activity is probably due to the limitations of the available recording techniques, which require physical restraints or cable connections and thus have restricted long-term EMG studies of natural behavior. However, since the introduction of radio-telemetry, wireless transmission of EMG signals has enabled recording from freely moving animals [21]. Recently, various EMG variables were also developed to assess the masticatory muscle activity. In particular, root mean square (RMS) and peak voltage have been reported as highly reliable and reproducible indicators of masticatory muscle activity [22].

In this study, the EMG activities of rabbit masseter muscles were measured before and after BTX-A injection. The aims of this study were to investigate the immediate, dose-dependent effects of a BTX-A injection using EMG in an animal model.

Methods

Ten male adult (>3 months of age) New Zealand white rabbits were used. This experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung, Republic of Korea (GWNU-2013-27). General anesthesia was administered by an intramuscular injection of 0.5 of mL tiletamine and zolazepam (125 mg/mL; Zoletil; Bayer Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and 0.5 mL of xylazine (10 mg/kg body weight; Rompun; Bayer Korea).

The rabbits were implanted with electrodes for telemetrical recording of the intramuscular EMG of the masseter muscle. The transmitter was placed in the shoulder, and bipolar electrodes were placed subcutaneously and led to an incision in the right submandibular region that was used for recording the muscle potentials. The electrodes were inserted into the masseter muscles and sutured at the muscle surfaces to prevent them from dislodging. Figure 1 shows a schematic configuration of the EMG measurement setup. The electrode signal was digitized at a sampling rate of 500 Hz and was wirelessly transmitted to a computer.

Muscle activity was continuously recorded for 8 hours, starting 12 hours after surgery when the animals had regained normal feeding behavior (Figure 2a). BTX-A was purchased from company (Meditox, Cheongwon, Korea). The amount of BTX-A to the rabbit was referenced from previous publication [23] and modified in high concentration. One day following surgery, the rabbits received a unilateral masseter injection of either 5 units (group 1, n = 5) or 20 units of BTX-A (group 2, n = 5). BTX-A was diluted with normal saline as 5 unit/ 0.1 ml. BTX-A was injected into the middle of the masseter muscle. Muscle activity was recorded immediately thereafter for 12 hours (Figure 2b).

The acquired signals were processed using MATLAB® (MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) to calculate the relevant parameters. The following two parameters are shown for each EMG signal: 1) Peak voltage from the rectified signal and 2) RMS value from the original signal.

The recorded data were analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The differences between the EMG values before and after injection were analyzed with paired t tests. The differences between groups were evaluated with independent sample t tests. The significance level for all tests was p < 0.05.

Results

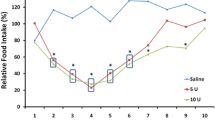

A summary of the recorded values is shown in Table 1. In group 1, the peak voltage before injection was 6.42 ± 0.50 mV and 4.73 ± 1.25 mV after injection. The difference before and after injection was statistically significant (P = 0.044). In group 1, the RMS before injection was 0.28 ± 0.07 mV and 0.12 ± 0.05 mV after injection. The difference between before and after injection was also statistically significant (P = 0.002). In group 2, the peak voltage was 6.49 ± 0.63 mV and 2.70 ± 0.98 mV before and after injection, respectively, and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). In group 2, the RMS was 0.31 ± 0.15 mV and 0.11 ± 0.10 mV before and after injection, respectively, and this difference was also statistically significant (P = 0.001).

When group 1 was compared with group 2, the relative peak voltage activity was 73.93 ± 18.88% and 41.14 ± 12.96%, respectively (Figure 3), and this difference between groups was statistically significant (P = 0.013). Additionally, the relative RMS activities in groups 1 and 2 were 41.68 ± 11.06% and 30.38 ± 11.84%, respectively (Figure 3), but this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Discussion

BTX-A has been widely used for cosmetic and therapeutic purposes [24]. BTX-A causes chemical denervation and the paralysis of associated muscles by preventing the release of membrane-bound acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction [25]. In this study, we demonstrated that the rabbit masseter muscle showed reduced peak voltage and RMS activity as measured EMG immediately after BTX-A injection. There are several methods to treat abnormal muscle contracture. Among them, very few studies have used EMG to evaluate the effects of BTX-A injection.

RMS and peak voltage are indicators of masticatory muscle activity [22]. After BTX-A injection, all of the EMG parameters were immediately decreased. Regarding peak voltage, both groups 1 and 2 exhibited significantly lower values when compared with pre-injection measurements. Peak voltage is generally regarded as the maximum muscle power of the measured muscle [26,27]. Therefore, when the peak voltage is reduced, maximum muscle power may also be decreased [28]. The decreased peak voltage might be due to the paralytic effects of BTX-A. RMS also showed similar results in that groups 1 and 2 RMS values were significantly different after injection. RMS measurements indicate the activity of the masseter muscle, and therefore, decreased RMS values suggest that masseter muscle activity was also reduced.

Group 2 had lower mean values for all of the parameters tested than did group 1. However, only the peak voltage of group 2 was significantly lower than that of group 1 (P = 0.013). Generally, the paralytic effect of BTX-A is dose dependent [29]. However, the local effects of BTX-A plateau at a certain dose beyond which increased BTX-A administration does not add therapeutic benefit [29]. Instead, the risk of systemic complications will be increased at such a dose. For the treatment of masseteric muscle hypertrophy, 5 units of BTX-A are injected into patients and a total of 25–30 units are administered on each side [30]. When group 1 was compared with group 2, the relative peak voltage activity was 73.93 ± 18.88% and 41.14 ± 12.96%, respectively (Figure 3). Though 20 units of BTX-A was 4-fold greater dose than the 5-unit BTX-A injection, the peak voltage values were reduced by only 30% in group 2 compared to group 1. Regarding the RMS values, the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Therefore, injecting increased doses of BTX-A into a single point might not have much value.

Factors such as time to onset of action are important to patients. However, there is limited information published concerning the time to onset for BTX-A treatment. The BTX-A-injected masseter muscles showed significantly lower average activity than did uninjected muscles at weeks 1 and 2 after injection [31]. Muscle activity remained low at least through week 10 in the injected muscle. The peak paralytic effects of BTX-A have been reported at 2 to 3 weeks post-injection, and muscular function typically starts to return by 3 months [31]. Additionally, masseter-induced bite force was dramatically decreased by 85% at week 3 and 65% at week 7 compared with controls [32]. However, the onset time of muscle weakness has been unclear in previous reports. In this study, the reduced EMG activities were observed immediately after the BTX-A injection. Therefore, BTX-A injection in patients with undesirable muscle activity may produce immediate therapeutic effects. In fact, a patient with post-traumatic open-bite could close his occlusion immediately after BTX-A injection [17].

BTX-A injection could also be considered for patients who receive orthognathic surgery to prevent post-operative relapse. Most postoperative relapse in orthognathic surgery occurs within 2 months post-surgery [33]. In another study, the EMG activity of the treated muscle remained low for at least 2 months, and then, activity slowly recovered. However, even after 3 months, the activity levels remained lower than those measured before injection [34]. Therefore, BTX-A injection might be helpful in preventing post-operative relapse in patients who received orthognathic surgery. However, this assumption requires further clinical study.

Our animal study had some limitations. Although the EMG was recorded for 8 hours before BTX injection as the baseline EMG activity, the bite patterns of the animals were not consistent. Additionally, the number of bites observed after BTX injection was decreased. The decreased biting activity following the BTX injection may be due to stress after the injection. Although the implanted electrode had greater positional stability than surface electrodes used in other animal experiments, it was not free from movement. These limitations may be overcome in a human study with a similar experimental setting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, rabbit masseter muscle activity was immediately reduced after BTX-A injection. When 5-unit BTX-A injections were compared with 20-unit injections, only the peak voltage was significantly decreased in the animals that received the greater dose.

Abbreviations

- BTX-A:

-

Botulinum toxin type A

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- TMD:

-

Temporomandibular disorder

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

References

Yamaguchi T, Satoh K, Komatsu K, Kojima K, Inoue N, Minowa K (2002) Electromyographic activity of the jaw‐closing muscles during jaw opening–comparison of cases of masseter muscle contracture and TMJ closed lock. J Oral Rehabil 29:1063–1068

Schatz J, Tsimas P (1994) Cephalometric evaluation of surgical-orthodontic treatment of skeletal Class III malocclusion. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 10:173–180

Williams JL, Rowe NL (1994) Rowe and Williams' Maxillofacial injuries, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Harkins S, Linford J, Cohen J, Kramer T, Cueva L (1990) Administration of clonazepam in the treatment of TMD and associated myofascial pain: a double-blind pilot study. J Craniomandib Disord 5:179–186

Wessberg GA, Schendel SA, Epker BN (1982) The role of suprahyoid myotomy in surgical advancement of the mandible via sagittal split ramus osteotomies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40:273–277

Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, Waite P (2004) Peterson's principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2nd ed. Hamilton, Ont B.C Decker Inc., London

Soboļeva U, Lauriņa L, Slaidiņa A (2005) The masticatory system-an overview. Stomatologija 7:77–80

Aoki KR (2001) Pharmacology and immunology of botulinum toxin serotypes. J Neurol 248:I3–I10

Simpson LL (1980) Kinetic studies on the interaction between botulinum toxin type A and the cholinergic neuromuscular junction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 212:16–21

Coté TR, Mohan AK, Polder JA, Walton MK, Braun MM (2005) Botulinum toxin type A injections: adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration in therapeutic and cosmetic cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:407–415

Crowner BE, Torres-Russotto D, Carter AR, Racette BA (2010) Systemic weakness after therapeutic injections of botulinum toxin a: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol 33:243

Persaud R, Garas G, Silva S, Stamatoglou C, Chatrath P, Patel K (2013) An evidence-based review of botulinum toxin (Botox) applications in non-cosmetic head and neck conditions. JRSM Short Rep 4:10

Guarda-Nardini L, Manfredini D, Salamone M, Salmaso L, Tonello S, Ferronato G (2008) Efficacy of botulinum toxin in treating myofascial pain in bruxers: a controlled placebo pilot study. Cranio 26:126–135

Lee SJ, McCall WD Jr, Kim YK, Chung SC, Chung JW (2010) Effect of botulinum toxin injection on nocturnal bruxism: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89:16–23

Brin MF, Fahn S, Moskowitz C, Friedman A, Shale HM, Greene PE et al (1987) Localized injections of botulinum toxin for the treatment of focal dystonia and hemifacial spasm. Mov Disord 2:237–254

Castro WH, Gomez RS, da Silva Oliveira J, Moura MD, Gomez RS (2005) Botulinum toxin type A in the management of masseter muscle hypertrophy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 63:20–24

Seok H, Park YT, Kim SG, Park YW (2013) Correction of post-traumatic anterior open bite by injection of botulinum toxin type A into the anterior belly of the digastric muscle: case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 39:188–192

Lee CJ, Kim SG, Kim YJ, Han JY, Choi SH, Lee SI (2007) Electrophysiologic change and facial contour following botulinum toxin A injection in square faces. Plast Reconstr Surg 120:769–778

Karsai S, Adrian R, Hammes S, Thimm J, Raulin C (2007) A randomized double-blind study of the effect of Botox and Dysport/Reloxin on forehead wrinkles and electromyographic activity. Arch Dermatol 143:1447–1449

Kim JH, Shin JH, Kim ST, Kim CY (2007) Effects of two different units of botulinum toxin type a evaluated by computed tomography and electromyographic measurements of human masseter muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg 119:711–717

Herzog W, Stano A, Leonard T (1993) Telemetry system to record force and EMG from cat ankle extensor and tibialis anterior muscles. J Biomech 26:1463–1471

Ernberg M, Schopka J, Fougeront N, Svensson P (2007) Changes in jaw muscle EMG activity and pain after third molar surgery. J Oral Rehabil 34:15–26

Görgü M, Silistreli OK, Karantinaci B, Ayhan M, Ozdemirkiran T, Celebisoy M (2006) Interaction of botulinum toxin type A with local anesthetic agents: an experimental study with rabbits. Aesthetic Plast Surg 30:59–64

Benedetto AV (1999) The cosmetic uses of botulinum toxin type A. Int J Dermatol 38:641–655

Klein AW (2004) Contraindications and complications with the use of botulinum toxin. Clin Dermatol 22:66–75

Van Eijden T, Blanksma N, Brugman P (1993) Amplitude and timing of EMG activity in the human masseter muscle during selected motor tasks. J Dent Res 72:599–606

Chandu A, Suvinen T, Reade P, Borromeo GL (2004) The effect of an interocclusal appliance on bite force and masseter electromyography in asymptomatic subjects and patients with temporomandibular pain and dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil 31:530–537

van Wessel T, Langenbach GE, Korfage JA, Brugman P, Kawai N, Tanaka E et al (2005) Fibre‐type composition of rabbit jaw muscles is related to their daily activity. Eur J Neurosci 22:2783–2791

Garcia A, Fulton JE (1996) Cosmetic Denervation of the Muscles of Facial Expression with Botulinum Toxin A Dose‐Response Study. Dermatol Surg 22:39–43

Kim HJ, Yum KW, Lee SS, Heo MS, Seo K (2003) Effects of botulinum toxin type A on bilateral masseteric hypertrophy evaluated with computed tomographic measurement. Dermatol Surg 29:484–489

Winn BJ, Sires BS (2013) Electromyographic Differences Between Normal Upper and Lower Facial Muscles and the Influence of Onabotulinum Toxin A. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 15:211–217

Rafferty KL, Liu ZJ, Ye W, Navarrete AL, Nguyen TT, Salamati A et al (2012) Botulinum toxin in masticatory muscles: Short-and long-term effects on muscle, bone, and craniofacial function in adult rabbits. Bone 50:651–662

Kim MJ, Kim SG, Park YW (2002) Positional stability following intentional posterior ostectomy of the distal segment in bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy for correction of mandibular prognathism. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 30:35–40

Korfage JA, Wang J, Lie SH, Langenbach GE (2012) Influence of botulinum toxin on rabbit jaw muscle activity and anatomy. Muscle Nerve 45:684–691

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ01121404) of the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

Park SY did most experiment and Park YW designed this experiment. Ji YJ and Park SW developed and set up the wireless recording device and analyzed the signal. Kim SG wrote the manuscript and did critical review on the experimental process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, SY., Park, YW., Ji, YJ. et al. Effects of a botulinum toxin type A injection on the masseter muscle: An animal model study. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 37, 10 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-015-0010-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-015-0010-8