Abstract

Protein-based materials are considered versatile biomaterials, and their biodegradability is an advantage for sustainable development. Bagworm produces strong silk for use in unique situations throughout its life stages. Rigorous molecular analyses of Eumeta variegata suggested that the particular mechanical properties of its silk are due to the coexistence of poly-A and GA motifs. However, little molecular information on closely related species is available, and it is not understood how these properties were acquired evolutionarily or whether the motif combination is a conserved trait in other bagworms. Here, we performed a transcriptome analysis of two other bagworm species (Canephora pungelerii and Bambalina sp.) belonging to the family Psychidae to elucidate the relationship between the fibroin gene and silk properties. The obtained transcriptome assemblies and tensile tests indicated that the motif combination and silk properties were conserved among the bagworms. Furthermore, our analysis showed that C. pungelerii produces extraordinarily strong silk (breaking strength of 1.4 GPa) and indicated that the cause may be the C. pungelerii -specific balance of crystalline/amorphous regions in the H-fibroin repetitive domain. This particular H-fibroin architecture may have been evolutionarily acquired to produce strong thread to maintain bag stability during the relatively long development period of Canephora species relative to other bagworms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Various fascinating protein-based materials found in nature are versatile representative biomaterials, and their biodegradability is an advantage [1]. Research on these high-performance materials can be of great help in artificial design and use efforts [2]. In particular, silk is a versatile biomaterial composed of silk fibroin that represents a unique combination of strength, toughness, and extensibility and is widely found in arthropods, mainly including members of the classes Insecta and Arachnida [3, 4]. The applications of silk have been optimized for clade-specific situations ranging from cocoon or egg sac formation to foraging, locomotion, or shelter production [3, 5]. The diversity of silk associated with the evolutionary and ecological adaptations of species may allow required physical properties to be designed and suggests a potential wide range of artificial applications.

Bagworms (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) are particularly strong silk-producing insects within Lepidoptera. Lepidopteran species produce cocoons using only thick, tough silk, and the composition of such silks has been well studied in a domesticated silkworm (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) and a saturniid (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) [6]. On the other hand, bagworm larvae not only produce a self-enclosing bag coated with silk and plant material but also use silk thread to hang their bag from the branch of a host tree [7, 8]. Although the cocoon hanging is known to be rare elsewhere, such as Callosamia promethea (family Saturniidae), it is one of the major features common to all bagworms. A detailed physical property analysis showed that the tensile strength of bagworm (E. variegata) silk (689 MPa) is nearly twice as high as that of domesticated silkworm silks (approximately 350 MPa) and shows up to half the average tensile strength of the dragline silk of orb-weaver spiders (approximately 1 GPa) [9, 10]. The available molecular information on E. variegata silk components, such as L/H-fibroin, sericin, fibrohexamerin, seroins, and protease inhibitors, has been increasing in recent years [11, 12]. In particular, we previously presented an E. variegata draft genome obtained via hybrid sequencing [13] and revealed all of the fibroin genes present based on a multiple-omics analysis [10]. The bagworm draft genome revealed a unique combination of repetitive motifs, polyalanine (A)n sequences and alternating glycine-alanine (GA)n sequences [10]. Most lepidopteran insects exhibit one of two such repetitive motifs in the fibroin gene. For example, saturniid fibroin genes contain an (A)n motif, and the domesticated silkworm genes contain a (GA)n motif [14]. Coexistence of the two motifs has not been found in other Lepidoptera, suggesting that this feature may underlie bagworm silk properties. Many examples of how mechanical properties change depending on the type of repetitive motifs are available [15, 16]. A more detailed understanding of the fibroin design rules based on comparative analysis among closely related species is required to produce artificial protein-based materials. However, the available molecular information on the Psychidae family is limited almost exclusively to E. variegata. Here, we performed transcriptome analysis and silk tensile test of Canephora pungelerii and Bambalina sp., which belong to the same subfamily (Oiketicinae, family Psychidae) as E. variegata to characterize the relationship between fibroin sequences and mechanical properties.

Methods

Bagworm and silk sampling

C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp. were collected from Yamagata Prefecture, Japan (May – Jul 2019) at the larval stage enclosed in a bag (Fig. 1a). The average size of the male C. pungelerii bag is 21.6 mm and the plant materials used for the bag are leaves and stems from various grasses. Bambalina sp. has a bag size of 37.3 mm and is known to use dead branches and leaves for its bag. These bagworms were identified based on the morphological characteristics of their bags and the sequence of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) based on the bagworm moth COI dataset [17]. These specimens were subjected to cDNA sequencing, and their silks were also used for the measurement of the mechanical properties (Fig. 1b, c). The silk samples were obtained from inside the bags. Since the samples were taken from the field, the nutritional conditions were not strictly controlled.

a Images of the bags of three bagworms (C. pungelerii, Bambalina sp., and E. variegata). The arrows indicate top to bottom when hanging. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on orthologous genes from four lepidopterans, including Nemophora sp. (family Adelidae) as the root. b Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) image of C. pungelerii silk and (c) Bambalina sp. silk. The C. pungelerii silk is about twice as thin and the surfaces are both smooth

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA extraction from bagworms was performed according to a field transcriptome protocol, as described previously [10, 18]. The bagworm larva was removed from its bag, immersed in 1 mL TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and homogenized in a metal cone by using a Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai). The extracted RNA was purified using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) with QIACube (Qiagen) automation. The quality of the purified total RNA was measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), and RNA integrity was estimated by electrophoresis using TapeStation 2200 with RNA Screen Tape (Agilent Technologies). Quantification was conducted using a Qubit Broad Range (BR) RNA assay (Life Technologies).

Library preparation for cDNA sequencing

The cDNA library for Illumina sequencing was prepared using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA samples (100 μg) were subjected to mRNA isolation by using NEBNext Oligo d(T)25 beads (skipping the second bead washing step). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using ProtoScript II Reverse Transcriptase and NEBNext Second Strand Synthesis Enzyme Mix. cDNA was end repaired using NEBNext End Prep Enzyme Mix before the ligation of the NEBNext Adaptor for Illumina and treatment with the USER enzyme. cDNA was amplified by PCR under the following conditions [20 μL cDNA, 2.5 μL Index Primer, 2.5 μL Universal PCR Primer, 25 μL NEBNext Q5 Hot Start HiFi PCR Master Mix 2x; 98 °C for 30 s and 12 cycles each of 98 °C for 10 s, 65 °C for 75 s and 65 °C for 5 min].

Sequencing and de novo assembly

A cDNA sequencing was performed on a NextSeq 500 instrument (Illumina, Inc.) using 150-bp paired-end reads with a NextSeq 500 High Output Kit (300 cycles). The quality of the sequenced reads was assessed with FastQC. The de novo assembly of the bagworm sequences was performed with Bridger (v. 2014-12-01) (pair_gap_length = 0 and k-mer = 31).

Gene annotation and fibroin curation

The assemblies were annotated with eggNOG-Mapper [19, 20]. Gene expression was estimated by using Kallisto version 0.42.2.1 as transcripts per million (TPM) values [21]. Homologous genes between the two bagworm species were identified according to bidirectional best hits (BBH) using a BLAST search with a 1.0e-20 threshold. Bagworm fibroin curation was conducted based on a previously reported Spidroin Motif Collection (SMoC) algorithm [13]. This strategy is effective for the curation of long gene sequences containing heavily repetitive regions, such as spider fibroin [22, 23], and has also been verified in E. variegata [10]. The Illumina short reads were assembled in a de Bruijin graph, and a BLAST search was carried out on the contigs from the N/C-terminal regions using E. variegata L/H-fibroin as the query (GBP72856.1 and GBP83861.1). The obtained terminal sequence candidates were used as seeds for screening short reads with an exact match of extremely large k-mers up to the 5′-end. The short reads were aligned on the 3′-side of the matching k-mer to build a position weight matrix (PWM). Based on a strict threshold, the seed sequence was extended until the next repeat unit appeared.

Phylogenetics

Using HMMER (v 3.1b2) [24], the orthologous gene set was obtained from the bagworm assemblies and from Nemophora sp. (family Adelidae) as the root sample [25]. The 456 orthologous genes collected were aligned with MAFFT (v. 7.273) (mafft -auto- localpair-maxiterate 1000) [26] and then trimmed with trimAI (v. 1.2rev59) [27]. A bootstrap analysis was conducted with RAxML (v. 8.2.11), and the phylogenetic tree was visualized with FigTree version 1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Measurement of mechanical properties

Surface morphology of the fibres were assessed by SEM (JCM 6000, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo Japan). Samples were mounted on an aluminum stub with a conductive tape backing and sputter-coated with gold for 1 min using a Smart Coater (JEOL) prior to SEM visualization at 5 kV. At least 8 individual mechanical stretching tests were performed for each silk type, with fibres were taken from two different bagworms for C. pungelerii, one bagworm for Bambalina sp.. The experimental setup was similar to those reported previously [10, 14]. Each fibre was attached to a rectangular piece of cardboard with a 5 mm aperture using 95% cyanoacrylate. The tensile properties of the fibres were measured using an EZ-LX universal tester (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a 1 N load cell, at a strain rate of 10 mm/min (0.033 s-1) at 25 °C and 48% relative humidity. For each tensile test, the cross-sectional area of an adjacent section of the fibre was calculated based on the SEM images.

Protein secondary structure data

We used values calculated in previous studies from the fibroin protein secondary structure data of spiders or closely related species. Spider silk structures were calculated by Raman spectromicroscopy [28], and the crystallinity of bagworm silk was estimated from the wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) profile [12].

Results

De novo transcriptome analysis of two bagworms and the corresponding phylogenetic tree

cDNA for transcriptome sequencing was synthesized from mRNA samples extracted from whole bagworm larvae. Illumina sequencing produced over 38 million 150-bp paired-end reads from each bagworm sample. These sequence reads were assembled, and 99,286 contigs (N50: 1815 bp) from C. pungelerii and 68,362 contigs (N50: 2017 bp) from Bambalina sp. were obtained (Table 1). Transcriptome completeness was assessed according to the BUSCO v.4.0.5 completeness score [29], and the test with eukaryota_odb10 showed 95.7% completeness in C. pungelerii and 93.7% completeness in Bambalina sp. (Table 1). Using these assemblies, we obtained 465 orthologous genes common to the E. variegata genome and produced a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1a). The constructed bagworm phylogenetic tree showed early divergence of C. pungelerii, similar to previous studies [17]. Approximately 25,000 of the assembled contigs were assigned as protein-coding genes, and the BLAST search demonstrated that approximately 35% of the contigs were conserved between the two bagworms (Fig. 2a).

a The number of orthologous genes between C. pungelerii (Cpu) and Bambalina sp. (Bam) Among the assigned protein-coding contigs, 16,293 (Bambalina sp.) and 21,002 (C. pungelerii) genes had a TPM of 1 or higher, and the number of bidirectional best hits (BBH) between the two species was 6708. b Expression level of L/H-fibroin genes in the whole body of each individual. c Sequence alignment of the L-fibroin C-terminal region with E. variegata (Eva: GBP72856.1). d Sequence alignment of H-fibroin N/C-terminal regions and repetitive domains with E. variegata (GBP83861.1). The H-fibroin sequence was highly conserved among bagworms. The repetitive domain, represented as Rep, is divided into four motif regions: a poly-A region with glutamic acid in the centre (blue), a GA region (yellow), a linker region (light blue), and a GA region containing serine (green) as described in the box (repetitive domain architecture). From the previous SAXS analysis [12], it is predicted that the poly-A to GA region is the crystalline (β-sheet) region and the linker to GA region is the amorphous region

Fibroin genes

Fibroin gene sequences were searched in the assembled transcriptome references based on E. variegata L-fibroin and H-fibroin sequences (GBP72856.1 and GBP83861.1), and the N/C-terminal regions and several repetitive units were obtained in C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp., respectively. The mRNA expression of the obtained L/H-fibroin genes was confirmed by cDNA-seq in each larval body, and both genes were highly expressed (Fig. 2b). Curated bagworm fibroins were well conserved in the three bagworms (Fig. 2c, d). The H-fibroin sequences of both N/C-terminal regions were very similar, and the features of a short C-terminal region were observed to be shared (Fig. 2d). The repetitive domains were also very similar among the three bagworms, with no significant differences in motif sequences or the distribution of the amino acid frequency (Fig. 3a). The unique combination of (A)n and (GA)n motifs observed in the repetitive domains of E. variegata was absent in other lepidopteran insects but was clearly apparent in C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp. H-fibroins. The separation of poly-A sequences by glutamic acid residues was also observed in the Psychidae family. Contrary to the sequence similarity of the terminal and repetitive domains, differences in the length of certain repetitive motifs were observed. The repetitive domain of bagworm H-fibroin is divided into four regions: an (A)n motif region with a central glutamic acid (E), a pure (GA)n motif region, a linker composed of isoleucine (I) and valine (V), and a (GA)n motif region containing serine (S). Within these regions, the length of the two (GA)n motif regions flanking the linker varied greatly among bagworms. The two (GA)n motif regions in E. variegata and Bambalina sp. averaged 40 and 90 residues in length, respectively, whereas that of C. pungelerii was approximately half the size (Fig. 3b).

a Amino acid frequency of H-fibroin repetitive domains. The frequencies of C. pungelerii (Cpu) and Bambalina sp. (Bam) were significantly correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.98, p < 0.01). b Boxplot comparing the repeat lengths of each motif. (A) nE(A)n showed a common length of 23 residues, while the GA motifs in C. pungelerii (Cpu) showed only half the length of those in other bagworms, regardless of whether they contained serine or not

Mechanical properties of bagworm silk

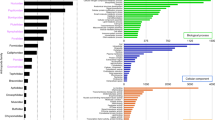

The mechanical properties of the bagworm silks produced from fibroins with different motif lengths of (GA)n motifs were examined by tensile tests. Using reeled silks from each bagworm bag, the following parameters were measured as mechanical properties: tensile strength (MPa), Young’s modulus (GPa), extensibility (%), and toughness (MJ/m3). These properties are summarized in Fig. 4. The newly calculated values for C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp. silks as well as that of E. variegata, showed higher tensile strength than has been found in other lepidopteran silks (Fig. 4a). Comparative analysis of the mechanical properties suggested that the length of the (GA)n motifs may have an impact on the tensile strength and Young’s modulus (Fig. 4a, b). The strength of C. pungelerii silk, which is composed of short (GA)n motif H-fibroin (Fig. 3b), was nearly twice as high as those other bagworm silks. The obtained tensile strength of 1.4 GPa and Young’s modulus of 1.3 GPa are currently the highest recorded among lepidopteran species.

Mechanical properties, including tensile strength (a), Young’s modulus (b), extensitivity (c), and toughness (d), in each lepidopteran family, including Psychidae (C. pungelerii (Cpu), Bambalina sp. (Bam), and E. variegata (Eva)), Bombycidae (B. mori (Bmo), and Saturniidae: S. ricini (Sri), A. yamamai (Aya), A. pernyi (Ape), and A. assama (Aas)). The tensile strength and Young’s modulus of C. pungelerii silk were significantly higher than those of other lepidopteran silks (**: p < 0.01; t-test). Each plot represents a separate silk sample. The data for Eva are from [10], and Bmo, Sri, Aya, Ape, and Aas are from previous study [14]

On the other hand, motif length did not change other mechanical properties, such as extensibility or toughness. The potential impact of the motif length difference in H-fibroins on the mechanical properties was verified using secondary structure data. The protein secondary structures were obtained from synchrotron radiation measurement data [12, 28], and mechanical property data were taken from [9, 10, 14, 30]. Although the crystalline and amorphous region data for C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp. was not measured in this study, the analysis of the relationship between the ratio of crystalline and amorphous regions and the mechanical properties based on previous studies showed that only tensile strength decreased with the ratio of the crystalline region (Fig. 5). Hence, these results are meant only as a reference, but the balance of the crystalline/amorphous region has an impact on the tensile strength, which may explain the strength of the silk produced from C. pungelerii H-fibroin.

The summarized relationship between the balance of crystalline/amorphous regions and mechanical properties based on previous studies. The higher the ratio of crystalline regions is, the lower the tensile strength. The fibroin structure data of Tncv (Trichonephila clavipes), Tned (Trichonephila edulis), Sric (Samia cynthia ricini), and Bmor (Bombyx mori) were obtained from [28], and those for Evar (Eumeta variegata) were obtained from [12]. Each mechanical property value was taken from previous studies, Tncv [9]:, Tned [30]:, Sric and Bmor [14]:, Evar [10]:, respectively

Discussion

We prepared transcriptome references for C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp., which are closely related to genome-sequenced species E. variegata, and confirmed the conservation of the unique motifs in H-fibroins and the mechanical properties of bagworm silks among these species. The results strongly suggested that the bagworm-specific motif is the key to the characteristic mechanical properties of the bagworm silks.

The bagworm H-fibroin structure based on the motifs in the repetitive domain has been discussed previously. The WAXD and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) patterns of E. variegata silk indicate that the poly-A and GA motifs correspond to crystalline and amorphous regions, respectively [12]. This structural model follows the stress-induced helix-to-sheet structural phase transition [31, 32]. In the fibres spun by bagworms, poly-A and pure (GA)n motifs are responsible for forming β-sheets, and linker and (GA)n motifs including serine are form the amorphous region [12]. As these repetitive units are assembled to form the hierarchical nanofibril structure, the motif balance is strongly related to the mechanical properties of bagworm silk. Therefore, the change in the balance of crystalline/amorphous regions may partially explain why C. pungelerii silk showed more than twice the tensile strength of other silks while maintaining the poly-A and linker sequence sizes. Incidentally, we should be cautious here about whether we can directly compare the data from previous studies. In particular, the mechanical properties are susceptible to the measurement methods, equipment, humidity, temperature, and even differences between individuals [33]. Figure 4 contains data from the previous studies [10, 14], all measured under the same conditions (EZ-LX universal tester with a 1 N load cell, at a strain rate of 10 mm/min at 25 °C and 48% relative humidity, see Methods). Any new comparisons in the future will need to be observed according to this standard.

Then, the question arises of why Oiketicinae silk has become stronger than that of other bagworms? The reason may have been to stably protect the larvae and eggs during the evolution of a wingless phenotype. All females of the subfamily Oiketicinae show a complete loss of wings in the pupal and adult stages. Wingless bagworm females are widely studied, and in many species, the wing discs that develop in the final larval stage degenerate during the prepupal or pupal stages through apoptosis [34, 35]. However, females of the subfamily Oiketicinae have lost the ability to develop wing discs during larval-pupal metamorphosis [36, 37]. Therefore, the subfamily Oiketicinae shows the most advanced established form of wing loss in the family Psychidae, and the independent clade is systematically supported [17]. Furthermore, within the Oiketicinae clade, C. pungelerii is phylogenetically divergent from Bambalina sp. and E. variegata (Fig. 1a). It is not well understood how different the lifestyle of C. pungelerii is from those of other species, but differences have been observed in terms of the shape and construction of the bag. Small flattened plant materials are often used to produce Bambalina bags (Fig. 1a). The bag is densely coated with such materials without gaps and therefore generally exhibits a hard consistency. On the other hand, in the bags of C. pungelerii, branches of varying lengths are used as surface materials. Because it is largely only the bases of these branches and leaves that are attached by silk threads (Fig. 1b, c), the bag surface is less dense and is generally soft and elastic [38]. In addition, the durability and stability required for C. pungelerii bags may be different from those of other bagworms. The development time of E. variegata is approximately 1 year, while that of Canephora unicolor (a close relative of C. pungelerii) is reported to be up to 730 days [7]. On the other hand, there are relatively few host plant families upon which C. unicolor hangs its bags. There are few potential host plants that can be selected in nature, and it is believed that the strength of the link with the host plant is the key to C. unicolor survival. Differences in bag material assembly and development time may have been the cause of the strong threads of C. pungelerii, even though the bag size is approximately four times smaller than that of E. variegata.

Omics analyses, such as genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic analyses, can reveal the molecular background of protein-based materials. The search for new protein-based materials is currently becoming easier and faster, especially with the multiple standardization projects for genome information [39,40,41,42,43]. Comprehensive research allows comparative analysis by increasing the amount of curated information. The present study suggested that the percentage of crystalline regions may affect the mechanical properties of biomaterials. Such linkage of biochemistry and biophysics will contribute to the further development of the artificial design of highly functional structural proteins.

Conclusions

Despite being closely related species, the silk threads of C. pungelerii and Bambalina sp. were a large difference in the mechanical properties. In particular, the tensile strength of C. pungelerii silk threads was much stronger than those of any other lepidopteran. This research has shown that one reason for this may be the balance of crystalline/amorphous regions in the H-fibroin repetitive domain, as shown by omics analysis. De novo transcriptome analysis has established their gene references, including new bagworm H-fibroin sequences, and the amorphous region of C. pungelerii was relatively short, which may have led to the high tensile strength. Our suggestion about the relationship between structural balance and the mechanical property of a structural protein will be helpful for future biomaterial research and industrial applications.

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequence reads used for de novo assembly and expression analysis were submitted to DDBJ SRA (sequence read archive). The accession numbers of the raw sequence reads are DRR227299 (C. pungelerii) and DRR227298 (Bambalina sp.). The assemblies are available in DDBJ under accession numbers ICRH01000001-ICRH01099286 (C. pungelerii) and ICRG01000001-ICRG01068362 (Bambalina sp.). Each L/H-fibroin gene sequence is submitted as ICRH01099286 (C. pungelerii L-fibroin), ICRG01068362 (Bambalina sp. L-fibroin), ICRH01099284-ICRH01099285 (C. pungelerii H-fibroin), and ICRG01068360- ICRG01068361 (Bambalina sp. H-fibroin).

References

Abascal NC, Regan L. The past, present and future of protein-based materials. Open Biol. 2018;8(10):180113.

Desai MS, Lee SW. Protein-based functional nanomaterial design for bioengineering applications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2015;7(1):69–97.

Craig CL. Evolution of arthropod silks. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:231–67.

Sutherland TD, Young JH, Weisman S, Hayashi CY, Merritt DJ. Insect silk: one name, many materials. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:171–88.

Lucas F. Spiders and their silks. Discovery. 1964;25:20–6.

Goldsmith MR, Shimada T, Abe H. The genetics and genomics of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:71–100.

Rhainds M, Davis DR, Price PW. Bionomics of bagworms (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Annu Rev Entomol. 2009;54:209–26.

Wolff JO, Lovtsova J, Gorb E, Dai Z, Ji A, Zhao Z, et al. Strength of silk attachment to Ilex chinensis leaves in the tea bagworm Eumeta minuscula (Lepidoptera, Psychidae). J R Soc Interface. 2017;14(128):20170007.

Swanson BO, Blackledge TA, Beltrán J, Hayashi CY. Variation in the material properties of spider dragline silk across species. Appl Physics A. 2006;82(2):213–8.

Kono N, Nakamura H, Ohtoshi R, Tomita M, Numata K, Arakawa K. The bagworm genome reveals a unique fibroin gene that provides high tensile strength. Commun Biol. 2019;2:148.

Tsubota T, Yoshioka T, Jouraku A, Suzuki TK, Yonemura N, Yukuhiro K, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of the bagworm moth silk gland reveals a number of silk genes conserved within Lepidoptera. Insect Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12846.

Yoshioka T, Tsubota T, Tashiro K, Jouraku A, Kameda T. A study of the extraordinarily strong and tough silk produced by bagworms. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1469.

Kono N, Arakawa K. Nanopore sequencing: review of potential applications in functional genomics. Develop Growth Differ. 2019;61(5):316–26.

Malay AD, Sato R, Yazawa K, Watanabe H, Ifuku N, Masunaga H, et al. Relationships between physical properties and sequence in silkworm silks. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27573.

Rising A, Johansson J. Toward spinning artificial spider silk. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(5):309–15.

Scheibel T. Spider silks: recombinant synthesis, assembly, spinning, and engineering of synthetic proteins. Microb Cell Factories. 2004;3(1):14.

Niitsu S, Sugawara H, Hayashi F. Evolution of female-specific wingless forms in bagworm moths. Evol Dev. 2017;19(1):9–16.

Kono N, Nakamura H, Ito Y, Tomita M, Arakawa K. Evaluation of the impact of RNA preservation methods of spiders for de novo transcriptome assembly. Mol Ecol Resour. 2016;16(3):662–72.

Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Coelho LP, Szklarczyk D, Jensen LJ, von Mering C, et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through Orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(8):2115–22.

Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Heller D, Hernandez-Plaza A, Forslund SK, Cook H, et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D309–D14.

Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(5):525–7.

Kono N, Nakamura H, Mori M, Tomita M, Arakawa K. Spidroin profiling of cribellate spiders provides insight into the evolution of spider prey capture strategies. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15721.

Kono N, Nakamura H, Ohtoshi R, Moran DAP, Shinohara A, Yoshida Y, et al. Orb-weaving spider Araneus ventricosus genome elucidates the spidroin gene catalogue. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8380.

Eddy SR. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7(10):e1002195.

Kawahara AY, Breinholt JW. Phylogenomics provides strong evidence for relationships of butterflies and moths. Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281(1788):20140970.

Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80.

Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1972–3.

Lefevre T, Rousseau ME, Pezolet M. Protein secondary structure and orientation in silk as revealed by Raman spectromicroscopy. Biophys J. 2007;92(8):2885–95.

Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(19):3210–2.

Madsen B, Shao ZZ, Vollrath F. Variability in the mechanical properties of spider silks on three levels: interspecific, intraspecific and intraindividual. Int J Biol Macromol. 1999;24(2–3):301–6.

Yoshioka T, Tashiro K, Ohta N. Molecular orientation enhancement of silk by the hot-stretching-induced transition from alpha-helix-HFIP complex to beta-sheet. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17(4):1437–48.

Giesa T, Arslan M, Pugno NM, Buehler MJ. Nanoconfinement of spider silk fibrils begets superior strength, extensibility, and toughness. Nano Lett. 2011;11(11):5038–46.

Yazawa K, Malay AD, Masunaga H, Norma-Rashid Y, Numata K. Simultaneous effect of strain rate and humidity on the structure and mechanical behavior of spider silk. Communications Mater. 2020;1(1):10.

Niitsu S, Kobayashi Y. The developmental process during metamorphosis that results in wing reduction in females of three species of wingless-legged bagworm moths, Taleporia trichopterella, Bacotia sakabei and Proutia sp. (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). EJE. 2008;105(4):697–706.

Niitsu S, Sims I, Ishizaki T. Morphology and Ontogeny of Wing Bud Development During Metamorphosis in Females of the Wingless Bagworm Moth Epichnopterix Plumella (Denis & Schiffermueller, 1775) (Psychidae); 2011.

Niitsu S, Lobbia S, Izumi S, Fujiwara H. Female-specific wing degeneration is triggered by ecdysteroid in cultures of wing discs from the bagworm moth, Eumeta variegata (Insecta: Lepidoptera, Psychidae). Cell Tissue Res. 2008;333(1):169–73.

Niitsu S. Postembryonic development of the wing imaginal discs in the female wingless bagworm moth Eumeta variegata (Lepidoptera, Psychidae). J Morphol. 2003;257(2):164–70.

Sugimoto M. A comparative study of larval cases of Japanese Psychidae (Lepidoptera) (2). Jpn J Entomol. 2009;12:17–29.

i5K Consortium. The i5K Initiative: advancing arthropod genomics for knowledge, human health, agriculture, and the environment. J Hered. 2013;104(5):595–600.

Scientists GCo, Bracken-Grissom H, Collins AG, Collins T, Crandall K, Distel D, et al. The global invertebrate genomics Alliance (GIGA): developing community resources to study diverse invertebrate genomes. J Hered. 2014;105(1):1–18.

Koepfli KP. Paten B, genome KCoS, O'Brien SJ. The genome 10K project: a way forward. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2015;3:57–111.

Boomsma JJ, Brady SG, Dunn RR, Gadau J, Heinze J, Keller L, et al. The global ant genomics Alliance (GAGA). Myrmecological News. 2017;25:61–6.

Lewin HA, Robinson GE, Kress WJ, Baker WJ, Coddington J, Crandall KA, et al. Earth BioGenome project: sequencing life for the future of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(17):4325–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Shuhei Niitsu for the morphological identification of the moths as well as Yuki Takai and Naoko Ishii for technical support in the sequencing analysis.

Funding

This work was funded by a Nakatsuji Foresight Foundation Research Grant, the Sumitomo Foundation (190426), KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) (21H02210), the ImPACT Program of Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan), Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas B (MEXT), and research funds from the Yamagata Prefectural Government and Tsuruoka City, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. designed the entire project, analysed all the data, and wrote the manuscript; N.K. and K.A. performed transcriptome sequencing and assembly; N.K. and K.A. managed the computer resources; H.N. collected all samples from field; A.T. and K.N. examined mechanical properties. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

H.N. is an employee of Spiber Inc., a venture company selling brewed protein products. However, the design of all study procedures was conducted by N.K. of Keio University, and Spiber Inc. had no role in the study design, data analysis, or data interpretation. N. K, A.T., K.N., and K.A. declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kono, N., Nakamura, H., Tateishi, A. et al. The balance of crystalline and amorphous regions in the fibroin structure underpins the tensile strength of bagworm silk. Zoological Lett 7, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-021-00179-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-021-00179-7