Abstract

Background

Globally, there has been an increase in the percentage of women in their reproductive ages who need modern contraceptives for family planning. However, in Chad, use of modern contraceptive is still low (with prevalence of 7.7%) and this may be attributable to the annual increase in growth rate by 3.5%. Social, cultural, and religious norms have been identified to influence the decision-making abilities of women in sub-Saharan Africa concerning the use of modern contraceptives. The main aim of the study is to assess the association between the health decision-making capacities of women in Chad and the use of modern contraceptives.

Methods

The 2014–2015 Chad Demographic and Health Survey data involving women aged 15–49 were used for this study. A total of 4,113 women who were in sexual union with information on decision making, contraceptive use and other sociodemographic factors like age, education level, employment status, place of residence, wealth index, marital status, age at first sex, and parity were included in the study. Descriptive analysis and logistic regression were performed using STATA version 13.

Results

The prevalence of modern contraceptive use was 5.7%. Women who take health decisions with someone are more likely to use modern contraceptives than those who do not (aOR = 2.71; 95% CI = 1.41, 5.21). Education, ability to refuse sex and employment status were found to be associated with the use of modern contraceptives. Whereas those who reside in rural settings are less likely to use modern contraceptives, those who have at least primary education are more likely to use modern contraceptives. Neither age, marital status, nor first age at sex was found to be associated with the use of modern contraceptives.

Conclusion

Education of Chad women in reproductive age on the importance of the use of contraceptives will go a long way to foster the use of these. This is because the study has shown that when women make decisions with others, they are more likely to opt for the use of modern contraceptives and so a well-informed society will most likely have increased prevalence of modern contraceptive use.

Plain language summary

The use of modern contraceptives remains a pragmatic and cost-effective public health intervention for reducing maternal mortality, averting unintended pregnancy and controlling of rapid population growth, especially in developing countries. Although there has been an increase in the utilization of modern contraceptives globally, it is still low in Chad with a prevalence rate of 7.7%. This study assessed the association between the health decision-making capacities of women in Chad and the use of modern contraceptives. We used data from the 2014 − 2015 Chad Demographic and Health Survey. Our study involved 4,113 women who were in sexual union and with complete data on all variables of interest. We found the prevalence of modern contraceptive utilization at 5.7%. Level of education of women, women who can refuse sex and employment status were found to be significantly associated with the use of modern contraceptives. Whereas those who reside in rural settings are less likely to use modern contraceptives, those who have at least primary education are more likely to use modern contraceptives. Our study contributes to the efforts being made to increase the utilisation of modern contraceptives. There is a need to step up contraceptive education and improve adherence among Chad women in their reproductive years. In the development of interventions aiming at promoting contraceptive use, significant others such as partners and persons who make health decisions with or on behalf of women must be targeted as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Women in their reproductive age with the need for family planning satisfied by modern contraceptive method has seen a steady increase globally, from 73.6% in the year 2000 to 76.8% in the year 2020 [1, 2]. Some reasons ascribed to this mild change include limited access to services, as well as cultural and religious factors [3]). However, these barriers are being addressed in some regions, and this accounts for an increase in demand for modern methods of contraception [2].

According to the World Health Organization, the proportion of women with needs for modern methods of contraception has been stagnant at 77% from 2015 to 2020 [2]. Globally, the number of women using modern contraceptive methods has increased from 663 million in 2000 to 851 million in 2020 [2]. In 2030, it is projected that an additional 70 million women will be using a modern contraceptive method [2]. In low to middle-income countries, the 214 million women who wanted to avoid pregnancy were not using any method of contraception as of 2020 [2]. Low levels of contraceptive use have mortality and clinical implications [3]. However, about 51 million in their reproductive age have an unmet need for modern contraception [1]. Maternal death and new born mortality could be reduced from 308,000 to 84,000 and 2.7 million to 538,000 respectively, if women with intentions to avoid pregnancy were provided with modern contraceptives [4].

Low prevalence in the use of modern contraceptives has been linked to negative events such as maternal mortality and unsafe abortion in Africa [5,6,7]. Women with low fertility intentions in sub-Saharan Africa, record the lowest prevalence rate of modern contraceptive use [8].

The use of modern contraceptive remains a pragmatic and cost-effective public health intervention for reducing maternal mortality, averting unintended pregnancy and controlling rapid population growth especially in developing countries [3, 9]. Beson, Appiah & Adomah-Afari, [3] highlight that knowledge and awareness per se do not result in the utilization of modern contraceptives [3]. Cultural and religious myths and misconceptions tend to undermine the use of modern contraception [10,11,12]. Ensuring access and utilization of contraceptives has benefits extending beyond just the health of the population [3]. Amongst these include sustainable population growth, economic development and women empowerment [2, 3].

Nonetheless. predominantly in SSA, women do not have the decision-making capacity to make decisions pertaining to their health [13]. Although this has proven to be an efficient driver for improved reproductive health outcomes for women [14, 15]. To improve efforts on contraceptive usage in Africa, people are encouraged to make positive reproductive health decisions to prevent unintended pregnancy and other sexually transmitted infections since these steps would lead to the reduction of maternal mortality and early childbirth amongst women [14].

At an estimated population growth of 3.5% per year, Chad’s population growth is considered to be growing at a relatively fast pace [16]. This trend in growth may be ascribed to the country’s high fertility and low use of contraceptives [16]. In Africa, Chad had been found to have the lowest prevalence of modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa despite its recorded growth from 5.7% to 2015 to 7.7% in 2019 [8, 17]. UN Women [18] data also showed that a lot need to be done in Chad to achieve gender equality with about 6 out of 10 women aged 20–24 years married before age 18 and about 165 of women in their reproductive age reporting being victims to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the year 2018. Studies indicate that social and religious norms have undermined women’s rights and self-determination in Chad [19-21] which affects their health decision-making capacity negatively. This situation makes it challenging for women in their reproductive age in Chad to be of independent mind when making decisions about the use of modern contraception. Though the use of contraception in many parts of the world had been found to yield immense benefits such as low levels of maternal mortality and morbidity, and to a larger extent influence economic growth and development [2, 3]. It has become necessary to investigate the health decision-making capacity and modern contraceptive utilisation among sexually active women in Chad. Findings from this study will provide stakeholders and decision-makers with evidence that will guide policymaking to improve access and utilisation of modern contraceptives in Chad.

Materials and methods

Data source

The study used data from the current Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in Chad 2104 − 2015. The 2014–2015 Chad Demographic and Health Survey (CDHS) aimed at providing current estimates of basic demographic and health indicators. It captured information on health decision making, fertility, awareness, and utilization of family planning methods, unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, skilled birth attendance, and other essential maternal and child health indicators [22].

The survey targeted women aged 15–49 years. The study used DHS data to provide holistic and in-depth evidence of the relationship between health decision-making and the use of modern contraceptives in Chad. DHS is a nationwide survey collected every five-year period across low- and middle-income countries. A stratified dual-stage sampling approach was employed. Selection of clusters (i.e., enumeration areas [EAs]) was the first step in the sampling process, followed by systematic household sampling within the selected EAs. For the purpose of this study, only women (15–49 years) in sexual unions (marriage and cohabitation) who had complete cases on all the variables of interest were used. The total sample for the study was 4,113.

Study variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study was “contraceptive use” which was derived from the ‘current contraceptive method’. The responses were coded 0 = “No method”, 1 = “folkloric method”, 2 = “traditional method,” and 3 = “modern method”. The existing DHS variable excluded women who were pregnant and those who had never had sex. The modern methods included female sterilization, intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD), contraceptive injection, contraceptive implants (Norplant), contraceptive pill, condoms, emergency contraception, standard day method (SDM), vaginal methods (foam, jelly, suppository), lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), country-specific modern methods, and respondent-mentioned other modern contraceptive methods (e.g., cervical cap, contraceptive sponge). Periodic abstinence (rhythm, calendar method), withdrawal (coitus interruptus), and country-specific traditional methods of proven effectiveness were considered as traditional methods while locally described methods and spiritual methods (e.g., herbs, amulets, gris-gris) of unproven effectiveness were the folkloric methods. To obtain a binary outcome, all respondents who said they used no method, folkloric, traditional, were put in one category and were given the code “0 = No” whereas those who were using the modern method were also put into one category and given the code “1 = Yes.”

Explanatory variables

Health decision-making capacity was the main explanatory variable. For health decision-making capacity, women were asked who usually decides on respondent’s health care. The responses were respondent alone, respondent and husband/partner, husband/partner alone, someone else, and others. This was recorded to respondent alone = 1, respondent and someone (respondent and husband/partner, someone else, and others) = 2, and partner alone = 3. Similarly, some covariates were included based on theoretical relevance and conclusions drawn about their association with modern contraceptive utilisation [13, 14, 23]. These variables are age, place of residence, wealth quintile, employment status, educational level, marital status, age at first sex, and parity.

Analytical technique

We analysed the data using STATA version 13. We started with descriptive computation of modern contraception utilization with respect to health decision-making capacity and the covariates. We presented these as frequencies and percentages (Table 1). We conducted Chi-square tests to explore the level of significance between health decision-making capacity, covariates, and modern contraceptive utilization at a 5% margin of error (Table 2). In the next step, we employed binary logistic regression analysis in determining the influence of health decision-making capacity on modern contraceptive utilization among women in their reproductive ages as shown in the first model (Model I in Table 3). We presented the results of this model as crude odds ratios (cOR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. We further explored the effect of the covariates to ascertain the net effect of health decision-making capacity on modern contraceptive utilization in the second model (Model III in Table 3) where adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were reported. Normative categories were chosen as reference groups for the independent variables. Sample weight was applied whilst computing the frequencies and percentages so that we could obtain results that are representative at the national and domain levels. We used STATA’s survey command (SVY) in the regression models to cater for the complex sampling procedure of the survey. We assessed multicollinearity among our co-variates with Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and realized that no multicollinearity existed with a mean VIF = 3.7.

Results

Socio-demographics and prevalence of modern contraceptive use

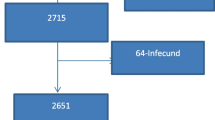

Among the respondents who participated in this study, 91% of them are married and about three-quarters of them (73.3%) have partners that are sole decision-makers regarding health issues (Table 1). Most of the respondents (79.8%) reside in rural settings with 69.5% having no education and about half (56.4%) between the ages of 20 and 34 (Table 1). A higher proportion of the respondents (56%) are not able to refuse sex when demanded. The prevalence of modern contraceptive use is 5.7% [CI = 5.46–5.91] (see Fig. 1).

Association between use of modern contraceptive and the predictor variables

As shown in Table 3, in both the adjusted and the unadjusted models, respondents who take health decisions with someone are more than two times (aOR = 2.71; 95% CI = 1.41, 5.21 and OR = 2.38; 95% CI = 1.28, 4.42 respectively) likely to decide on using contraceptives than respondents who decide alone. It has also been observed that having at least a primary education positively affect the likelihood of using modern contraceptives; primary education (aOR = 2.34; 95% CI = 1.56, 3.50); secondary or higher education (aOR = 4.02; 95% CI = 2.44, 6.60) (see Table 3). Likewise, people who reside in rural areas are 53% less likely to patronize modern contraceptives (aOR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.27, 0.82) than their counterparts who live in urban areas (see Table 3). Furthermore, women who are employed have higher odds of using contraceptives than those who are unemployed (aOR = 2.24; 95% CI = 1.54, 3.28). Along with that, women who have given birth at least four (4) times are 61% more likely to use modern contraceptives (aOR = 2.71; 95% CI = 1.41, 5.21) than those with no birth experience. It was observed that women who can refuse sex have higher odds of using modern contraceptives (aOR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.14, 2.27) relative to those who are unable to refuse sex (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study was essential since the ability of sexually active women to make significant decisions on their health including choices of modern contraceptive use (i.e., condom use) can lead to good reproductive health [24]. We observed that the prevalence of modern contraceptive use in Chad among women in sexual union was 5.7%. Generally, about three-quarters (73.3%) of respondents who were married (91%) had partners as the sole decision-makers regarding their health issues, a finding similar to that of a study conducted in Ghana where only a quarter of women in the study took healthcare decisions single-handedly [25]. However, in a multi-country assessment, it was revealed that about 68.66% of respondents across the 32 nations studied could make decisions on their reproductive health [14]. The discrepancy might be attributable to the diverse research populations and the number of nations investigated.

Furthermore, parties to decision-making regarding the health of women play an important role in the usage of contraceptives. It was found that respondents who took health decisions with someone were more than two times likely to decide on using contraceptives than respondents alone. Similar result was seen in Burkina Faso [26] and Mozambique [27] as spousal decision with women had a positive influence on the utilization of contraception. In terms of decisions taken solely by partners, women were 18% less likely to report an intention to use contraceptives [27]. Again, it was revealed in Pakistan that women whose partners were sole decision-makers were less likely to use contraception. This shows that a woman’s inability to discuss and make decisions on health, especially on family planning issues can negatively affect the use of modern contraception.

Education has been recognised as a strong determining factor of contemporary contraception use. It exposes women to factual information as well as convinces their partners of the need for contraception [28]. This is relevant as we also observed that having at least a primary education induces higher odds of using modern contraceptives. Although the study establish education to be significantly associated with contraption use, a study conducted to measure the trend in the use of contraception in 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa reported that an increase in the proportion of the study participants with secondary education did not affect the use of contraception [29]. In agreement with our finding, a high level of education has been found to increase the likelihood of using modern ways of delaying birth in women living in Uganda [30]. A plausible explanation to this is that as the level of education of women increases, women are more empowered to take charge of their health decision-making capacity. Since education empowers women to have autonomy over their reproductive rights [23].

With regards to the place of residence, we found that urban women were more likely to use modern contraceptives as compared to their counterparts in rural areas. a possible explanation is that women in urban areas may have better access to information, and are more likely to be interested in education, hence, the use of modern contraceptives to delay childbirth. Other reasons may be poor transportation access, long distances to access health facilities and shortage of contraceptives in the rural areas as compared to in the urban areas [31].This corroborates the findings of Apanga et al., [32] which they ascribed to the fact that there is a high prevalence of late marriage in urban areas as compared to rural areas [33]. Hence, there is a possibility that women in urban areas are likely to use modern contraceptives to avoid unwanted pregnancies.

Consistent with prior studies in Ghana, [3, 34] women who are working had a higher likelihood of utilizing contraception methods than those who are unemployed. The reason for this is because, compared to their non-working peers, the working class may be willing to do everything to maintain their employment and have more time for their occupations instead of having children, especially given their capacity to acquire contraceptives in comparison to their non-working peers. Also, working women are expected to have the financial backing to be able to make health decisions concerning their reproductive health. It is, therefore, no surprise that we found women within the richest wealth quintile to have the highest likelihood of utilizing modern contraceptives.

Finally, women who have given birth to at least four (4) children are more likely to use contraceptives than those with no birth experience. A plausible explanation is that multiparous women may not want more children hence resort to the use of modern contraceptives to either delay the next pregnancy or stop childbirth. This finding is similar to previous reports from Ethiopia and Tanzania which reported that as the number of living children increases, so does the usage of modern contraceptives [35, 36].

Strength and limitations

We used a large dataset comprising 4,113 women aged between 15–49 which makes our results compelling. Findings from this study are also based on rigorous logistic regression. Despite these strengths, the study had some notable shortcomings. To begin with, the study’s cross-sectional methodology limits causal inferences between respondents’ individual factors and modern contraceptive use. Second, because most questions were answered using the self-reporting approach, there is a risk of social desirability and memory bias in the results. Furthermore, because this study only included women, the conclusions do not incorporate the perspectives of spouses. Finally, we believed that variables like cultural norms and health-care provider attitudes would be relevant to investigate in the context of this study, however, such variables were not included in the DHS dataset.

Conclusion

The study revealed that modern contraceptive utilization is very low among sexually active women in Chad. We conclude that health decision-makers, education, occupation status [working], higher parity and women’s ability to refuse sex have positive association with modern contraceptive utilization among sexually active women in Chad. There is a need to step up modern contraceptive education and improve adherence among women in their reproductive years. In the development of interventions aiming at promoting modern contraceptive use, broader contextual elements must be prioritized. For instance, significant others such as partners and persons who make health decisions with or on behalf of women need to be targeted.

Data availability

Data used for the study is freely available to the public via https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- AIC :

-

Akaike Information Criterion.

- aOR :

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio.

- BIC :

-

Bayesian Information Criterion.

- CDHS :

-

Chad Demographic and Health Survey.

- cOR :

-

Crude Odds Ratio.

- DHS :

-

Demographic and Health Survey.

- EAs :

-

Enumeration Areas.

- ICC :

-

Intra-Cluster Correlation.

- IUD :

-

Intrauterine Device.

- LAM :

-

Lactational amenorrhea method.

- LMICs :

-

Lower-and middle-income countries.

- LR :

-

Likelihood Ratio.

- MLRM :

-

Multilevel Logistic Regression Model.

- PSU :

-

Primary Sampling Unit.

- SDM :

-

Standard Day Method.

- SRHR :

-

Sexual and Reproductive Health Right.

- SSA :

-

Sub-Saharan Africa.

- VIF :

-

Variance Inflation Factor.

- WHO :

-

World Health Organisation.

References

Kantorová V, Wheldon MC, Ueffing P, Dasgupta AN. Estimating progress towards meeting women’s contraceptive needs in 185 countries: A Bayesian hierarchical modelling study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(2):e1003026.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on self-care interventions: self-administration of injectable contraception (No. WHO/SRH/20.9):. World Health Organization; 2020.

Benson P, Appiah R, Adomah-Afari A. Modern contraceptive use among reproductive-aged women in Ghana: prevalence, predictors, and policy implications. BMC women’s health. 2018 Dec;18(1):1–8.

Darroch JE, Sully E, Biddlecom A. Adding it up: investing in contraception and maternal and newborn health, 2017—supplementary tables. New York: The Guttmacher Institute; 2017.

Apanga PA, Adam MA. Factors influencing the uptake of family planning services in the Talensi District, Ghana. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015 Mar 6;20(1).

Eliason S, Awoonor-Williams JK, Eliason C, Novignon J, Nonvignon J, Aikins M. Determinants of modern family planning use among women of reproductive age in the Nkwanta district of Ghana: a case–control study. Reproductive health. 2014 Dec;11(1):1–0.

Orach CG, Otim G, Aporomon JF, Amone R, Okello SA, Odongkara B, Komakech H. Perceptions, attitude and use of family planning services in post conflict Gulu district, northern Uganda. Confl health. 2015 Dec;9(1):1–1.

Ahinkorah BO, Budu E, Aboagye RG, Agbaglo E, Arthur-Holmes F, Adu C, Archer aG, Aderoju YbG, Seidu A. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women with no fertility intention in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from cross-sectional surveys of 29 countries. Contracept Reprod Med. 2021;6:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-021-00165-6.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mukunya D. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptives utilization among female adolescents in Uganda. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01206-7.

Gueye A, Speizer IS, Corroon M, Okigbo CC. Belief in family planning myths at the individual and community levels and modern contraceptive use in urban Africa. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2015 Dec;41(4):191.

Hindin MJ, McGough LJ, Adanu RM. Misperceptions, misinformation and myths about modern contraceptive use in Ghana. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2014 Jan 1;40(1):30 – 5.

Wulifan JK, Mazalale J, Kambala C, Angko W, Asante J, Kpinpuo S, Kalolo A. Prevalence and determinants of unmet need for family planning among married women in Ghana-a multinomial logistic regression analysis of the GDHS, 2014. Contraception and reproductive medicine. 2019 Dec;4(1):1–4.

Achana FS, Bawah AA, Jackson EF, Welaga P, Awine T, Asuo-Mante E, et al. Spatial and socio-demographic determinants of contraceptive use in the Upper East region of Ghana. Reproductive health. 2015 Dec;12(1):29.

Ahinkorah BO, Hagan JE Jr, Seidu AA, Sambah F, Adoboi F, Schack T, Budu E. Female adolescents’ reproductive health decision-making capacity and contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: What does the future hold? PLoS ONE. 2020 Jul;10(7):e0235601. 15(.

Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Hubert A, Agbemavi W, Armah-Ansah EK, Budu E, Sambah F, Tackie V. What has women’s reproductive health decision-making capacity and other factors got to do with pregnancy termination in sub-Saharan Africa? evidence from 27 cross-sectional surveys. PLoS One. 2020 Jul 23;15(7):e0235329.

Yaya AM, Caroline G, Abderahim MN, Solene BH, Doungous DM, Marret H. Use of Female Contraception, Mixed and Multicentric Study in Chad. Am J Public Health. 2020;8(1):22–7.

Yaya S, Uthman OA, Ekholuenetale M, Bishwajit G. Women empowerment as an enabling factor of contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis of cross-sectional surveys of 32 countries. Reproductive health. 2018 Dec;15(1):1–2.

UN Women Data Hub [Internet]. Country Fact Sheet | Unwomen.org. 2013 [cited 2022 Sep 6]. Available from: https://data.unwomen.org/country/chad

Amzat J. The question of autonomy in maternal health in Africa: a rights-based consideration. Journal of bioethical inquiry. 2015 Jun;12(2):283–93.

Hindin MJ, Muntifering CJ. Women’s autonomy and timing of most recent sexual intercourse in Sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis. Journal of sex research. 2011 Nov 1;48(6):511-9.

Singh K, Bloom S, Brodish P. Gender equality as a means to improve maternal and child health in Africa. Health care for women international. 2015 Jan 2;36(1):57–69.

Institut National de la Statistique, des Études. Économiques et Démographiques (INSEED), Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP) et ICF International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples (EDS-MICS 2014–2015). Rockville, Maryland, USA: INSEED, MSP et ICF International. 2014–2015.

Mandiwa C, Namondwe B, Makwinja A, et al. Factors associated with contraceptive use among young women in Malawi: analysis of the 2015-16 Malawi demographic and health survey data. Contracept Reproductive Med 2018; 3: 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-018-0065-xpmid: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30250748.

Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Agbemavi W, Amu H, Bonsu F. Reproductive health decision-making capacity and pregnancy termination among Ghanaian women: Analysis of the 2014 Ghana demographic and health survey. J Public Health. 2021 Feb;29:85–94.

Budu E, Seidu AA, Armah-Ansah EK, Sambah F, Baatiema L, Ahinkorah BO. Women’s autonomy in healthcare decision-making and healthcare seeking behaviour for childhood illness in Ghana: Analysis of data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2020 Nov;9(11):e0241488. 15(.

Klomegah R. Spousal communication, power, and contraceptive use in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Marriage & Family Review. 2006 Dec 7;40(2–3):89–105.

Mboane R, Bhatta MP. Influence of a husband’s healthcare decision making role on a woman’s intention to use contraceptives among Mozambican women. Reproductive health. 2015 Dec;12(1):1–8.

Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, Adebimpe WO, Bamidele JO, Odu OO, Asekun-Olarinmoye IO, Ojofeitimi EO. Barriers to use of modern contraceptives among women in an inner city area of Osogbo metropolis, Osun state, Nigeria. Int J women’s health. 2013;5:647.

Emina JB, Chirwa T, Kandala NB. Trend in the use of modern contraception in sub-Saharan Africa: does women’s education matter?. Contraception. 2014 Aug 1;90(2):154 – 61.

Asiimwe JB, Ndugga P, Mushomi J, Ntozi JP. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use among young and older women in Uganda; a comparative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec;14(1):1–1.

Bekele D, Surur F, Nigatu B, Teklu A, Getinet T, Kassa M, Gebremedhin M, Gebremichael B, Abesha Y. Contraceptive prevalence rate and associated factors among reproductive age women in four emerging regions of Ethiopia: a mixed method study. Contracept Reproductive Med. 2021 Dec;6(1):1–3.

Apanga PA, Kumbeni MT, Ayamga EA, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 20 African countries: a large population-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e041103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041103.

Pradhan R, Wynter K, Fisher J. Factors associated with pregnancy among adolescents in low-income and lower middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:918–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-205128 pmid:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26034047

Nyarko SH. Prevalence and correlates of contraceptive use among female adolescents in Ghana. BMC women’s health. 2015 Dec;15(1):1–6.

Mohammed A, Woldeyohannes D, Feleke A, Megabiaw B. Determinants of modern contraceptive utilization among married women of reproductive age group in North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Reproductive health. 2014 Dec;11(1):1–7.

Lwelamira J, Mnyamagola G, Msaki MM. Knowledge. Attitude and Practice (KAP) towards modern contraceptives among married women of reproductive age in Mpwapwa District, Central Tanzania. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences. 2012 May 10;4(3):235 – 45.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Measure DHS for granting us data for this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KSA, EKA and KSD conceived the study. KSA performed the analysis. NS drafted the background. BEM drafted the results. RMA drafted the discussion. MA, EKA, BEM and KSD reviewed multiple drafts and proposed additions and change. KSA had the final responsibility to submit. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study used publicly available data from DHS. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the survey. The DHS Program adheres to ethical standards for protecting the privacy of respondents. The ICF International also ensures that the survey processes conform to the ethical requirements of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. No additional ethical approval was required, as the data is secondary and available to the general public. However, to have access and use the raw data, we sought and obtained permission from MEASURE DHS. Details of the ethical standards are available on http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adde, K.S., Ameyaw, E.K., Mottey, B.E. et al. Health decision-making capacity and modern contraceptive utilization among sexually active women: Evidence from the 2014–2015 Chad Demographic and Health Survey. Contracept Reprod Med 7, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-022-00188-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-022-00188-7