Abstract

Background

This paper reviews the classical and some particular factors contributing to earthquake-triggered landslide activity. This analysis should help predict more accurately landslide event sizes, both in terms of potential numbers and affected area. It also highlights that some occurrences, especially those very far from the hypocentre/activated fault, cannot be predicted by state-of-the-art methods. Particular attention will be paid to the effects of deep focal earthquakes in Central Asia and to other extremely distant landslide activations in other regions of the world (e.g. Saguenay earthquake 1988, Canada).

Results

The classification of seismically induced landslides and the related ‘event sizes’ is based on five main factors: ‘Intensity’, ‘Fault factor’, ‘Topographic energy’, ‘Climatic background conditions’, ‘Lithological factor’. Most of these data were extracted from papers, but topographic inputs were checked by analyzing the affected region in Google Earth. The combination and relative weight of the factors was tested through comparison with well documented events and complemented by our studies of earthquake-triggered landslides in Central Asia. The highest relative weight (6) was attributed to the ‘Fault factor’; the other factors all received a smaller relative weight (2–4). The high weight of the ‘Fault factor’ (based on the location in/outside the mountain range, the fault type and length) is strongly constrained by the importance of the Wenchuan earthquake that, for example, triggered far more landslides in 2008 than the Nepal earthquake in 2015: the main difference is that the fault activated by the Wenchuan earthquake created an extensive surface rupture within the Longmenshan Range marked by a very high topographic energy while the one activated by the Nepal earthquake ruptured the surface in the frontal part of the Himalayas where the slopes are less steep and high.

Finally, the calibrated factor combination was applied to almost 100 other earthquake events for which some landslide information was available. This comparison revealed the ability of the classification to provide a reasonable estimate of the number of triggered landslides and of the size of the affected area. According to this prediction, the most severe earthquake-triggered landslide event of the last one hundred years would actually be the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008 followed by the 1950 Assam earthquake in India – considering that the dominating role of the Wenchuan earthquake data (including the availability of a complete landslide inventory) for the weighting of the factors strongly influences and may even bias this result. The strongest landslide impacts on human life in recent history were caused by the Haiyuan-Gansu earthquake in 1920 – ranked as third most severe event according to our classification: its size is due to a combination of high shaking intensity, an important ‘Fault factor’ and the extreme susceptibility of the regional loess cover to slope failure, while the surface morphology of the affected area is much smoother than the one affected by the Wenchuan 2008 or the Nepal 2015 earthquakes.

Conclusions

The main goal of the classification of earthquake-triggered landslide events is to help improve total seismic hazard assessment over short and longer terms.

Considering the general performance of the classification-prediction, it can be seen that the prediction either fits or overestimates the known/observed number of triggered landslides for a series of earthquakes, while it often underestimates the size of the affected area. For several events (especially the older ones), the overestimation of the number of landslides can be partly explained by the incompleteness of the published catalogues. The underestimation of the extension of the area, however, is real – as some particularities cannot be taken into account by such a general approach: notably, we used the same seismic intensity attenuation for all events, while attenuation laws are dependent on regional tectonic and geological conditions. In this regard, it is likely that the far-distant triggering of landslides, e.g., by the 1988 Saguenay earthquake (and the related extreme extension of affected area) is due to a very low attenuation of seismic energy within the North American plate. Far-distant triggering of landslides in Central Asia can be explained by the susceptibility of slopes covered by thick soft soils to failure under the effect of low-frequency shaking induced by distant earthquakes, especially by the deep focal earthquakes in the Pamir – Hindukush seismic region. Such deep focal and high magnitude (> > 7) earthquakes are also found in Europe, first of all in the Vrancea region (Romania). For this area as well as for the South Tien Shan we computed possible landslide event sizes related to some future earthquake scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Review of major events

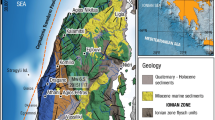

A series of extensive reviews of earthquake-triggered landslide events have been published since the first compilation presented by Keefer (1984) that became a milestone for related research. Keefer (1984) was the first to establish general seismic trigger thresholds indicating the (I) minimum earthquake magnitude needed to trigger landslides, (II) the maximum possible surface areas over which landslides of a specific type can be triggered by a single earthquake, (III) the maximum distance from the epicentre and the fault, at which a landslide could be triggered and (IV) the maximum possible number of induced landslides. Related statistics were first updated for more recent events (after 1980) by Rodriguez et al. (1999) and then again by Keefer (2002), mainly by using the same types of relationships. Common results of their analyses are: a) landslides may be triggered by an earthquake with a magnitude larger or equal than 4 (with very few exceptions, one presented in Table A in the Appendix); b) far more than 10,000 landslides could be induced by a single earthquake, over distances up to several hundreds of kilometres away from the epicentre or the fault plane and, thus, (c) within a total surface area of more than 100,000 km2. The most extreme landslide-triggering earthquake events indicated by those researchers are the Haiyuan-Gansu 1920, the Assam 1950, the Alaska 1964, the Peru 1970, the Guatemala 1976 and the Chi-Chi 1999 earthquakes. A less catastrophic but remarkable event was the Northridge earthquake in 1994 as it is the only M < 7 earthquake (Ms = 6.7) that may have triggered 11,000 landslides over an area of 10,000 km2 (Harp and Jibson 1996). Below, we will show that it is not easy to explain the enormous morphological impact of this specific earthquake. However, for two other events, the Chi-Chi 1999 and Wenchuan 2008 earthquakes, extremely high numbers and concentrations of earthquake-triggered landslides could clearly be related to a specific combination of factors (Gorum et al. 2011; Huang and Fan 2013): the extensive surface rupture of the activated fault inside a mountain range marked by extremely steep slopes and a relatively humid climate (see Fig. 1 showing the landslide distribution with respect to mountain topography and fault location for the Wenchuan 2008 earthquake). In this regard it should be noted that the general topographic, climatic and tectonic background conditions already turn this region into a landslide prone area.

Landslide and landslide dam distribution map of the area affected by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake showing 60,104 landslide initiation points and 257 landslide dams (by Gorum et al. 2011)

In many cases, the ‘Fault factor’ combining the relative location of the fault, its extent and mechanism, helps explain the general characteristics of earthquake-triggered landslide events, but it does not explain why some events trigger landslides at very far distances, such as the Ms = 5.8 Saguenay earthquake that induced landslides at unexpected large epicentral distances of more than 100 km. Rodriguez et al. (1999) related this far-distant triggering to the high susceptibility of sensitive clays to slope failure; Keefer (2002) added low regional seismic attenuation and local site amplification as reasons explaining distant landslide occurrences. The role of the low regional attenuation of seismic waves on the landslide triggering potential – especially in intraplate areas - was highlighted more recently by Jibson and Harp (2012) with the example of the 2011 Mineral, Virginia, earthquake, in North-Eastern U.S. This Mw = 5.8 earthquake with a focal depth of 6 km (reverse motion on N28°E/45°E oriented fault, not rupturing the surface) triggered small rock falls and slides at maximum epicentral distances of more than 200 km; the total area affected by slope instability thus by far exceeded the surface area potentially affected by seismic slope failures as predicted by any existing empirical law (see comparison of actual affected area with predicted extension areas in Fig. 2). A second factor added by Jibson and Harp (2012) explaining the extreme underestimation of affected surface area and epicentral distance by existing laws is the fact that those ones (including the one of Keefer and Wilson 1989) were partly based on older inventories mainly compiled from smaller areas near the epicentre. Thus, it is likely that those compilations just missed the far-distant (but generally rare) landslides.

Map showing the epicentral region of the 23 August 2011 Mineral, Virginia, earthquake (by Jibson and Harp 2012). The star indicates the epicentre; large crosses are landslide limits; triangles represent seismic recording stations with station codes indicated. Bold line: ellipse centred at the epicentre and passing through the observed limits (dashed where inferred beyond limits); the dotted line shows a polygon enclosing the observed landslides; the circle around the epicentre indicates the previous maximum distance limit for M 5.8 earthquake (Keefer 1984); filled circles show maximum (1500 km2) and average (219 km2) areas expected to experience landslides for an M 5.8 earthquake based on previous studies (Keefer 1984, 2002; Rodríguez et al. 1999)

Another case of distant triggering of landslides is presented by Jibson et al. (2006) for the Mw = 7.9 Denali Earthquake in 2002. However, here the 300 km distance of the farthest landslide measured from the epicentre is due to the fact that the epicentre is located at one end of a 300 km long fault rupture. The distance is strongly reduced if measured from the fault rupture. A similar observation was made by Gorum et al. (2011) for the Wenchuan Earthquake.

The far-distant triggering is an enigmatic topic that should have stimulated more interest among the scientific community. However, only a few researchers have focussed their attention on this problem, among them Delgado et al. (2011) as well as Niyazov and Nurtaev (2013, 2014) and Torgoev et al. (2013). Delgado et al. (2011) also consider local site amplification and high slope failure susceptibility (for slopes with Fs ~1 and thus also prone to static failure) as important reasons for the far-distant triggering that may further be enhanced by the general seismic and climatic conditions (e.g., repeated seismic activity due to aftershocks and intensive antecedent rainfall, respectively). The other cited researchers studied the remote effects (>200 km from epicentre) of deep focal earthquakes in the Hindukush – Pamir area. Havenith et al. (2013) also show that the impacts should not be considered as ‘anecdotic’ as some proved remotely triggered landslides caused enormous impacts such as the Baipaza landslide in Tajikistan (Fig. 3) triggered in 2002 by the Mw = 7.4 Hindukush earthquake at a hypocentral distance of more than 300 km. This landslide had dammed Vakhsh River with consequential impacts on the immediately upstream located hydro-power station that had to stop running for several months. These case histories highlight the importance to reassess hazards induced by deep focal earthquakes in other regions of the world, either along subduction zones or in specific continental areas such as the Hindukush – Pamir Mountains and in the Carpathians (Vrancea seismic region). In the next section we will analyse this effect more in detail.

Baipaza landslide triggered by the 2002 Hindukush earthquake (outlined in black) partially damming Vakhsh River (Tajikistan) with consequential inundation up to Baipaza Hydropower Station. Height of landside ~ 700 m, length ~ 1560 m (Google Earth image of 2007 still showing the rapids formed after landslide breach in 2002)

Methods

Classification of seismically induced landslides

Our classification of seismically induced landslide event sizes follows an ‘event by event’ approach rather than a statistical analysis of extensive databases, as published previously, e.g. by Keefer (1984, 2002) or others (Rodriguez et al. 1999). It is based on five main factors that were combined to assess the ‘size’ of an event in terms of potential number of triggered landslides and total affected area: ‘Intensity’, ‘Fault factor’, ‘Topographic energy’, ‘Climatic background’, ‘Lithological factor’. Those factors are estimated from readily available information, such as earthquake magnitude and hypocentral depth, time of the event, or they had to be compiled from generally more rare data on fault characteristics, regional surface morphology, antecedent rainfall or general climatic background of the affected region and the regional geology. Most of these data were extracted from papers, but topographic inputs were also checked by analysing the affected region in Google Earth, for some regions combined with studies of SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission) data (mostly with 90 m resolution that was adapted to the scale of the research). The combination and relative importance of the factors were tested through calibration based on well documented events (e.g. Haiti 2010, Wenchuan 2008) or on older events for which reliable extensive information was available such as for the Northridge 1994, Loma Prieta 1989, Guatemala 1976 and Peru 1970 earthquakes. This calibration is complemented by our expertise developed through studies of earthquake-triggered landslide events in Central Asia for which a series of examples are presented as well.

The complete table (Table A) of the classification of all 100 studied events is included in the Appendix, while the results for the 50 earthquakes marked by the highest numbers of triggered landslides (as estimated on the basis of our database) are also presented graphically in Fig. 4. The weights of the five main factors assigned to each event are also shown in Table A in the Appendix; they were obtained on the basis of the approach described more in detail for each factor below and summarised in Table 1. For clarity, the intermediate factors, the fault (rupture) location factor (FLF) describing its location with respect to the affected mountain region, the fault length (FLF), the fault type (FT) and the resulting ‘Fault factor’ (F) as well as the Arias Intensity (AI) values used for the ‘Intensity’ estimate are shown in a separate Table B in the Appendix. The weight of three of the main contributing factors is directly determined from available information: Topographic energy, Climatic background, and Lithological factor. However, for all factors also some arbitrary limits are introduced (see explanation below) to simplify the approach; thus, we acknowledge that the weighting strongly depends on expert opinion.

Graphs (events along Y-axis) showing the results of the classification for 50 earthquake events that are likely to have triggered most of the landslides – according to our database (see Appendix A, B) and related analysis. Left graph: the relative weight of the five contributing factors (see used symbols in legend) is indicated along the respective event bar. Right graph: the size of an event is shown (along X-axis) in terms of observed and predicted number of induced landslides (resp., red and black squares along the grey horizontal bar produced for each event) and total affected area (blue cross in the same line)

The ‘Intensity’ factor is based on the attenuation law for Arias Intensity AI (see Eq. 1 by Keefer and Wilson 1989) using as inputs the earthquake magnitude M and the distance. The distance parameter ‘R’ used here combines the hypocentral distance ‘D’ with an event-adapted epicentral distance as shown by Eq. 2. The adaptation concerns mainly the average distance of the landslide group to the epicentre that is qualitatively estimated by multiplying the magnitude M by a factor of 10, divided by two factors (see also Table 1 and explanation in the next paragraph), by the fault location factor FLF and by the fault type FT. The division by FLF takes into account for the reduction of the average epicentral distance, especially if the fault is located near the affected mountain region, i.e. for FLF > 1; the division by FT is justified by the fact that wave propagation from activated dip-slip faults with FT equal to 1.5 is generally less attenuated over distance than the one from strike-slip faults with FT = 1. Further, to reduce the partly overlapping contribution of the factors I and F for large earthquakes (with AI > 1 m/s), especially subduction earthquakes, and considering that for larger earthquakes the average AI will be comparatively smaller over a greater affected area, the square-root of AI is attributed to factor I.

Table 1 summarizes the weights or value ranges for the five factors and how they were obtained.

The ‘Fault factor’ combines the two aforementioned inputs FLF and FT with the fault length (FL). The weights attributed to the components (FLF, FT, FL) strongly depend on expert opinion: thus, we estimate that the location of the fault inside/near/outside a mountain range (values of FLF are respectively: 2/1.5/1) or the fault length (values of FL: 1, 2) have a greater influence on the landslide triggering potential than the fault type (values of FT: 1, 1.5). For the fault length FL contributing to the ‘Fault factor’ F only two values were considered: 1 if the fault length is smaller than 100 km, 2 if it is larger. Here we might also have used a continuously changing value, e.g. based on the logarithm (with basis 10) of the fault length. However, such a calculation would not have been possible for all, especially the older, events for which FL is not well known. Further, for very deep earthquakes, the fault length is not really a significant factor in this context – only the magnitude would have an impact on the landslide triggering potential (through the use of AI). Thus, for those deeper earthquakes, a value of 1 was set for FL. From Table 1 it can be inferred that the range of values attributed to the Fault factor is the largest one, as it is considered to the dominating factor.

The determination of the Topographic energy (TE) factor required the most extensive analysis as for the epicentral areas of all 100 events the maximum altitude difference had to be measured (mainly in Google Earth, for areas covered by our databases in Central Asia, Romania also with 90 m SRTM data) for sample surface areas of 10 by 10 km. On the basis of this study, five levels of TE were set: 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4. The value of 0.5 is attributed to relatively flat areas where landslides may develop only on minor slopes or bluffs (e.g., for the 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquake zone). The other values are attributed to hilly or mountainous areas. Among the zones affected by the 50 most severe events (shown in the table in Fig. 4) only the Longmenshan Mountains hit by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake are marked by a TE-value of 4. In Table A in the Appendix, a TE-value of 4 was also attributed to zones hit by earthquakes in the Hindukush (Hindukush events of 2002 and 2015) and in the Andes (Columbia event of 1995).

For setting the value of the ‘Climatic background’ condition factor CB a pure qualitative approach was applied as for many events only limited hydro-meteorological information is available. For all events, the general climatic conditions were taken into consideration: e.g., for intracontinental mountain areas marked by arid climate, such as for the zone affected by 1957 Gobi-Altai earthquake, a CB-value of 0.5 was selected, while to zones marked by a wet climate in sub-tropical or tropical areas a CB-value of 2 was generally attributed, such as for the regions affected, respectively, by the 2008 Wenchuan and the 1950 Assam earthquakes. Only for a few events information on the seasonal conditions or antecedent rainfall was found in published reports: e.g., the 1992 Suusamyr earthquake (in Table A in the Appendix) occurred during a very dry season; therefore, the minimum value of CB of 0.2 was set for this event. It should be noted that for many (especially older) events the climatic conditions are not or only poorly known; in those cases, a ‘neutral’ CB-value of 1 was used. The maximum weight of the ‘Climatic background’ is only 2 and thus maybe considered as ‘less’ important than the ‘Fault factor’ with a maximum weight of 6. However, the range of values covered by CB (0.2–2, with a max/min value ratio of 10) is almost as large as for F (0.5–6, with max/min ratio of 12).

The ‘Lithological factor’ LF was extracted from any published (and available) geological information. It ranges from 1 to 4; the value of 1 is used for zones with major presence of (hard or only partly weathered) bedrock, the value of 2 is used for areas with wide presence of weakly consolidated Tertiary (partly also Mesozoic) layers and 4 for areas extensively covered by loose Quaternary deposits. For some areas, setting this factor was not problematic as the presence of a certain type of lithology susceptible to slope failure is explicitly mentioned in the papers describing the events, such as the presence of thick loess cover in zones affected by earthquakes in China or Central Asia or the presence of volcanic soils in areas hit by subduction earthquakes in the Andes and in Central America. Those cases are described with more detail below. Certainly, the required geological information is not available for all epicentral areas (at least not in the papers describing the events); for those ones a LF value of 1 was used – this is the case for about 25 % of all events. It should be noticed that for those events we did not further study the geological maps that might have been published in national journals. From Table 1 it can be seen that we essentially use a kind of stratigraphic subdivision of LF, simply because this kind of information is more readily available than geotechnical data. Such a subdivision revealed to be widely applicable in Central Asia (see Havenith et al., 2015b), but we acknowledge that does not account for, e.g., the influence of deep weathering on slope stability. Thus, the classification of LF would require an extensive adaptation in the case of tropical regions.

On the basis of these five main factors, the event size is first computed in terms of potential number of earthquake-triggered landslides NL (see Table A in the Appendix) according to Eq. 3:

The potentially landslide-affected area AL is computed using the following Eq. 4:

Equation 3 is based on the assumption that the number of seismically triggered landslides NL is proportional to all five factors, augmented by a factor of 1000 estimated qualitatively through comparison with published landslide event size data. For the calculation of the affected landslide area AL we also assume the same proportionality between AL and the product of four of the five main factors (I, TE, CB, LF), multiplied by the fault type component, by the earthquake magnitude M and by the square of the hypocentral depth D. The ‘Fault factor’ F was not entirely taken into consideration for the calculation of AL as the fault location (FLF) or length (FL) components do not have a proved effect on the extent of the affected areas, which is more depending on the earthquake magnitude and hypocentral depth (see also Lei 2012: deep large earthquakes are known to have triggered landslides at farther distances; comparison with those events showed that even the square of D best explains the extent of areas affected by seismic landslides). FLF and FL rather control the concentration of the landslides within the affected area (as shown by Gorum et al., 2011, for the Wenchuan earthquake). Only the fault type seems to have an effect on the size of the landslide-affected area AL: notably, for dip-slip faults (including subduction faults) a farther reaching effect can be expected in the hanging wall (AL is increased by a factor FT = 1.5). These considerations are supported by the studies of Tatard and Grasso (2013) who noticed that dip-slip earthquakes may trigger landslides at larger distances than oblique slip events; they also show that especially those earthquakes producing extensive surface ruptures generally trigger landslides over relatively smaller distances from the fault. The selection of factors contributing to AL is further constrained by the information on the 2008 Wenchuan and 1999 Chi-Chi earthquakes for which reliable data are available as well as by data on a series of subduction and intraplate earthquakes that were not accompanied by surface fault rupture in the landslide-affected areas (e.g. El Salvador 2001, Saguenay 1988).

The graph in Fig. 4 shows that the event marked by the largest potential number of landslides (NL > 90,000) is the Wenchuan earthquake. This is due to the aforementioned combination of various factors clearly favouring the occurrence on an extreme event: the high magnitude (Mw = 7.9) and associated large ‘Intensity’ (see yellow ellipse along first bar in the graph in Fig. 4), the maximum value attributed to the ‘Fault factor’ (F = 6, see location of red circle along the bar in Fig. 4) related to the location of the activated mainly dip-slip fault with FT = 1.5 (note: part of the fault was also strike-slip; see Gorum et al. 2011) with a length larger than 100 km (FL = 2) inside a mountain range (FLF = 2) marked by a very high ‘Topographic energy’ (TE = 4, see location of brown cross along first bar in Fig. 4), the humid climate of the affected region (CB = 2, see blue dot along first bar in Fig. 4). In this case, we expect, however, that the ‘Lithological factor’ did not contribute to the event size as there is only limited soft soil cover in the area (LF = 1: there is no indication of soil slides in Gorum et al. 2011), even though the comment above concerning the influence of deep weathering of rocks on slope stability may also be applicable to some areas affected by the Wenchuan earthquake. Nevertheless, it can be seen that the estimated potential number of triggered landslides and the size of the affected area indicated in Fig. 4 and Table A in the Appendix (NL = 93,883, AL = 53,586) clearly exceeds the number and size observed by Gorum et al. (2011): NL ~ 60,000; AL ~ 35,000. However, our computed values are smaller than those recently published by Shen et al. (2015): NL ~ 200,000 landslides; AL ~ 100,000 km2. So, the estimated NL and AL values are within the range of the NL and AL values published by those two teams.

The large numbers of landslides potentially triggered by the 1950 Assam and 1920 Haiyuan-Gansu events (NL ~ 74,400, NL ~ 36,500, classified second and third, respectively) are strongly controlled by the high earthquake magnitudes of more than 8, resulting in larger shaking intensities as well. For the 1950 Assam event, the other factors are similar to those of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, but the final NL value is a bit smaller as the activated fault surface rupture is not directly located in the affected mountain region (FLF = 1.5); further, the ‘Topographic energy’ of the epicentral area and nearby mountains is less pronounced (TE = 3) than in the Longmenshan Mountains affected by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. In addition to its high magnitude (M = 8.5), another particular factor contributed to the severity of the 1920 Haiyuan-Gansu event: the ‘Lithological factor’ (LF = 4), as most of the area is covered by thick loess deposits. In this case, the ‘Fault factor’ and ‘Topographic energy’ seem to be less important (F = 4; TE = 1) compared to the two first events (see also Li et al. 2015), while the important role of the Lithological factor is documented by the following notes by Zhang (1995): ‘…areas with intensity of 8 … here the damage caused by the slides was more serious than the primary ones caused by the quake. Based on field survey, abnormal 9 to 10 intensities were recorded here’. Zhang (1995) added that ‘these landslides were not only controlled by the intensity of the earthquake, but by the structure of the subsoil’. It should be noticed that such an intensity of 8 (on Chinese Seismic Intensity Scale, CSIS) was recorded over 50,000 km2 (Zhang 1995).

Zhang and Wang (2007) also observed that loess earth-flows triggered by the Haiyuan-Gansu earthquake had developed on relatively gentle slopes compared to those triggered by rainfall in the same region. These observations highlight the particular susceptibility of loess areas to seismic ground failure, such as it was clearly shown by Derbyshire et al. (2000) analysing geological hazards affecting the loess plateau of China. In addition to those notes directly concerning the 1920 Haiyuan-Gansu earthquake, we also refer to the observations by Danneels et al. (2008) who proved that a thick cover of loess (especially if present on the top of slopes) can induce strong amplification of the seismic motion. Thus, the maximum value of 4 was attributed to the ‘Lithological factor’ of the Haiyuan-Gansu event due to both the weak stability of loess-covered slopes and to site amplification. The same maximum value of LF = 4 is also attributed to events affecting zones covered by sensitive clays (e.g., for the regions affecting the 1988 Saguenay, Canada, earthquake; see also Keefer 2002) and soils of volcanic origin (e.g., 2001 El Salvador earthquake; see Evans and Bent 2004).

As indicated above, values of the ‘Climatic background’ conditions factor CB are typically higher (CB = 2) in the humid tropical or sub-tropical regions (South China, Central America, some regions in South America, and Southeast Asia) where this factor may then either reduce the static slope stability or favour induced seismic ground effects related to increased pore water pressures such as liquefaction; both mechanisms, separately or combined, contribute to a higher landslide susceptibility, also during earthquakes. This was probably the case for the 2008 Wenchuan, the 1991 Valle de la Estrella (Costa Rica), the 1987 Reventador (Ecuador) and the 1990 Luzon (Philippines) earthquakes, among others. However, for a series of earthquake events affecting regions marked by a relatively arid climate or during dry seasons (with CB < 1), the landslide triggering potential may also be reduced; we estimate that this was the case for the recent 2015 Nepal, the 2011 Tohoku or the 2003 Altai events, among others. The smallest value of CB of 0.2 was attributed to one single event presented in Fig. 4: the 1977 Caucete (San Juan) earthquake in 1977 that occurred in a very arid area in Western Argentina. The aridity of regions in Central Asia also explains why events such as the 1911 Kemin (M ~ 8) or the Suusamyr (M = 7.3) earthquakes triggered relatively few landslides – though both of them triggered at least one giant rockslide. The NL-values presented in Table A in the Appendix (and, for the Kemin event, also in Fig. 4) even clearly overestimate the known observed number of landslides (typically several dozens, possibly one hundred but not more than 1000 as estimated for the Kemin earthquake in Fig. 4). Similar earthquakes would have triggered far more landslides in a comparable topographic context but marked by a wetter climate or if the earthquake had occurred during the wet season (the 1992 Suusamyr earthquake occurred in August 1992, at the end of the dry summer season).

The classification of the events according to the landslide-affected area does not follow the same trends as the one in terms of the number of triggered landslides. This is mainly due to the reduced influence of the ‘Fault factor’ and the increased magnitude and focal depth impact. Therefore, earthquakes most likely triggering landslides at extreme distances are those having a very deep hypocentre – though there are also well-known exceptions to this rule, such as the 2011 Mineral, Virginia, earthquake in the Eastern U.S. (Jibson and Harp 2012). In Fig. 4, the graph indicates the largest extents of landslide-affected areas for subduction earthquakes. Thus, according to our estimates, the 1970 Ancash (Peru), the 2001 El Salvador and 1964 Alaska earthquakes might have triggered landslides over an area of more than 70,000 km2. The problem is that those estimates may not be easily verified; at least, for the 1964 Alaska subduction event an extreme AL-value has been indicated by Keefer (1984, 2002): AL = 269,000 km2. This value is much larger than the one predicted here. This could be due to the fact that we assumed a relatively strong bedrock geology for the area (LF = 1), while the geology must be highly variable over tens of thousands of square kilometres. Areas covered by loose deposits or those presenting a topography susceptible to amplified shaking can thus be affected by landslides at much larger distances: e.g. the Sherman rock avalanche was triggered at a distance of more than 100 km from the epicentre of the 1964 Alaska earthquake, from a mountain called Shattered Peak (Shreve 1966). The high ‘Lithological factor’ value of 4 also probably explains why the 1988 Saguenay earthquake triggered landslides at greater distances as indicated by Rodriguez et al. (1999) and Keefer (2002). In Fig. 4 and Table A in the Appendix, we indicate a relatively large affected area of more than 3000 km2; this means that landslides could be triggered at more than 40 km from the epicentre. Actually, even much larger distances of more than 100 km are indicated for this event by Rodriguez et al. (1999). The prime examples of earthquakes potentially triggering landslide movements at very far distances (> > 100 km) are the deep focal events in the Hindukush-Pamir seismic region. This potential has been proved by Niyazov and Nurtaev (2010, 2013, and 2014) and Torgoev et al. (2013) on the basis of landslide case histories in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, some located at a distance of more than 500 km from the hypocentre. Also in Tajikistan, the impacts of the distant Hindukush-Pamir earthquakes on slope movements are known as shown above with the example of the Baipaza landslide that dammed Vakhsh River in 2002. Niyazov and Nurtaev (2013, 2014) relate the higher susceptibility of the slopes to (partly) fail during such distant earthquakes to liquefaction phenomena developing in loess deposits through the impact of very low frequency shaking – even though the Arias Intensity could be well below 0.1 m/s (see also computed intensities for Hindukush earthquakes in Table A in the Appendix). Niyazov and Nurtaev (2013, 2014) further highlight the importance of the climatic factor (here, CB) for the distant seismic triggering, showing that most of the landslides were induced during the wet spring season, when the static factor of safety of the slopes would be the lowest due to increased pore pressures. Another region where deep focal earthquakes are known to have triggered landslides is the Vrancea seismic area in the South-Eastern Romanian Carpathians, where 4 earthquakes with Mw > 7.4 have been recorded during the last two centuries. According to Georgescu (2003), the 1802 earthquake (“the Great Quake”) is considered to be the most severe one ever recorded in this area in terms of magnitude (Mw 7.8–7.9, 150 km depth) and among the most important in terms of intensity (I0I = IX-X MSK). The Vrancea region is considered to be the most important intermediate-depth earthquake area of Europe inducing effects that may be recorded as far as Russia (NE) and Bulgaria-Serbia (SW). Historical earthquakes in Vrancea are known to have triggered landslides at very large distances (250–300 km). As a consequence of the November 1940 earthquake (Mw = 7.7, 150 km depth), Radu and Spânoche (1977) reported numerous geohazards (ground fracturing and at least 40 shallow and medium-seated landslides accompanied by ground-water level disturbances), favoured by the wet conditions induced by the overall very humid 1937–1940 time period (annual mean precipitation exceeded by 13–38 %). The very large majority of the above–mentioned processes was recorded within an elliptical zone (300 by 200 km) elongated according to a NE-SW direction and marked by the 8 degrees MSK intensity isoline. Angelova (2003) states that all the M > 5.5 Vrancea earthquakes have left ground effects and damage throughout Bulgaria. Particularly, the 1977 event (Mw = 7.4, 94 km depth) was marked by numerous coseismic processes like cracks and fissures (in Bregare, Cape Emine and Silistra at epicentral distances of 160–290 km), falls (from coastal cliffs, caves, steep river banks, limestone ridges in Tyulenovo, Galata, Iskrets at epicentral distances of 270–380 km) and slides (in Razgrad, Popovo, Silistra at epicentral distances of 210–260 km). Mândrescu (1981) outlined two main areas in Romania with ground deformations that appeared following the 1977 earthquake: a) the outer Paleogene Flysch Carpathians, Neogene Molasse Subcarpathians and (mainly) the southern Moldavian Plateau (Upper Neogene-Quaternary loose deposits) areas at an epicentral distance of 50–80 km, where slides, falls and collapses, soil and rock cracks and fissures were the prevailing processes; b) the Romanian plain area (and the large floodplains of the transversal rivers in their Subcarpathian sector and also the Danube floodplain, at an epicentral distance of 120–310 km away, affected by river bank collapses, soil cracks and fissures and liquefaction phenomena (that appeared at very large distances of 220–310 km). Most of the landslides (12 coseismic cases are confirmed with a surface area of 1–10 ha) occurred during the earthquake or immediately after it, while only a few (namely 4) acted as post-seismic failures (24 h to 5 weeks). The quite small number of landslide events induced by the 1977 earthquakes can be attributed to the relatively dry climatic conditions during that period, marked by a pluviometric record that was 40 % below the monthly average values of 30–90 mm.

In order to exemplify the possible use of this classification for predictions over long terms we computed ‘worst-case’ scenarios of earthquake-triggered landslide events for two geographically and seismotectonically very distinct regions: the Vrancea seismic region and the South Tien Shan (see ‘Scenarios’ in Tables 2 and 3 below). These two regions are marked by the highest regional M > 7 earthquake activity in Europe and Central Asia (north of the Hindukush), respectively. The worst-case scenarios combine the general (permanent) regional conditions with the maximum possible earthquake magnitude (not exceeding the highest historical magnitude by more than 0.3 units) and very wet conditions (adapted to regional climatic context): for the Vrancea area we consider Mmax = 8 and CB = 2 and for the South Tien Shan Mmax = 7.8 and CB = 1. The CB value is higher for the Vrancea area as this region is more likely to be affected by very wet conditions than the South Tien Shan that is typically marked by a semi-arid climate. In the South Tien Shan, the CB-value of 1 would only be reached during a particularly wet spring - early summer season. According to the estimates presented at the end of Table A, the maximum number of landslides that may be triggered by a single earthquake in Vrancea would be less than 1000 (~760) while it may even exceed 50,000 for the South Tien Shan. The much higher predicted number of landslides triggered by an earthquake in the South Tien Shan compared with Vrancea – even though the magnitude and CB-value are more severe for this latter region - is due to two main factors: first, in the Vrancea region very large earthquakes typically occur at a depth of more than 150 km while they are relatively shallow in the South Tien Shan (the depth is normally less than 20 km); second, the slopes are on average much steeper and higher in the South Tien Shan than in the South-Eastern Carpathians. These results are supported by historical evidence as the South Tien Shan has already been hit by a major landslide triggering earthquake event (Khait 1949) while for the Vrancea region such an important event has not been reported in historical documents. However, it should be noticed that this general predictive approach does not fully take into account some far-distant effects (see also examples shown above) that are likely to be more pronounced for the deep focal Vrancea earthquakes than for the shallow earthquakes in the South Tien Shan.

Conclusions

The main goal of the classification of earthquake-triggered landslide events is to help improve total seismic hazard assessment over short and longer terms – especially for mountain regions. The classification may thus contribute to a better prediction of very distinctive geological-geomorphic hazards induced by an earthquake if the geologic, topographic and climatic context is well defined. An application could be the short-term prediction right after an earthquake (e.g. to facilitate emergency aid), or it could be used for scenario modelling (e.g., for critical infrastructure).

The classification is based on five factors considering the (I) shaking intensity, (II) the combined fault location-type and length characteristics, the (III) general topographic context (average slope steepness and height for a region), (IV) climatic background and temporary hydro-meteorological conditions as well as (V) regional and local lithological properties. The weighting of all five factor values is based on expert knowledge combined with calibration using known events, considering both the general and particular case histories. The highest weight (6) was attributed to the ‘Fault factor’; the other factors all received a smaller weight (2–4). The high weight of the ‘Fault factor’ (based on location in/outside mountain range, fault type and length) is strongly constrained by its importance highlighted by the Wenchuan event. For this earthquake, among all studied events, the highest number of landslides (NL) has been observed and mapped within a well-defined area (Gorum et al. 2011: NL ~ 60,000; Shen et al. 2015: NL ~ 200,000). This high number of triggered landslides is due to a combination of several factors favouring seismic slope instability: (I) the large earthquake magnitude (Mw = 7.9), (II) the presence of a mountain range marked by a very steep and high slopes and affected by (III) generally wet hydro-meteorological conditions. However, a similar combination of factors could also be observed for other events (notably, Assam 1950 and Chi-Chi 1999); actually, it is possible that the M > 8 Assam earthquake triggered a similar high number of landslides (see, e.g. Keefer 1984), but this number is not proved; for the Mw = 7.6 Chi-Chi earthquake the proved number of triggered landslides is clearly smaller (NL ~ 20,000). Therefore, we think that the key element to explain the extreme geomorphic impact of this earthquake is the development of an extensive surface rupture (length > 300 km) of the activated (mainly thrust-type) fault inside a mountain range (for the Assam 1950 event, a similar large surface rupture occurred near but mainly outside the mountain range and for the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, the surface rupture was less extensive, ~ 100 km).

Considering the general performance of the classification-prediction, it can be seen that for many studied events the estimated number of seismically triggered landslides fits the observed one; however, for many others this number is also overestimated (e.g., for events in Central Asia, such as Kemin 1911, Khait 1949 and Suusamyr 1992 as well as, possibly, for some subduction events, such as Peru 1970 and El Salvador 2001); only for a very few cases (e.g., San Francisco 1906 and Northridge 1994) the number of seismically triggered landslides is underestimated. In this regard it should be noticed that ‘underestimation’ was restricted through the calibration of the factor values and their combination. For several events (especially the older ones), the overestimation of the number of landslides can be partly explained by the incompleteness of the published catalogues. Therefore, we considered ‘overestimation’ of the number of triggered landslides as less constraining than ‘underestimation’. However, we also know that for events investigated in Central Asia overestimation of the number of triggered landslides might be due to an inappropriate weighting of the hydro-meteorological conditions that does not fully take into account the very arid climate favouring slope stability in some mountain regions. This observation is also likely to be applicable to other arid mountain regions, such as to some parts of the Andes marked by extreme dry hydro-meteorological conditions.

Frequent overestimation of the number of landslides contrasts with numerous cases of underestimation of the observed extension of the area affected by co-seismically triggered landslides. Good fits of the affected areas were mainly obtained for well-described intracontinental events, especially those for which fault characteristics are known (e.g. Wenchuan 2008, Haiti 2010). A prominent event for which the reported size of landslide-affected area was clearly underestimated is the Mw = 9.2 Alaska earthquake in 1964. According to Keefer (1984, 2002) this earthquake would have triggered slope failures over an area of more than 200,000 km2, while any prediction of this area based on a reasonable factor weighting and combination produced a value of less than 100,000 km2. Underestimation of areas affected by seismic slope failures is due to the fact that some particularities cannot be taken into account by such a general approach. First, we used the same seismic intensity attenuation law for all events, while attenuation laws are dependent on regional tectonic and geological conditions; thus, it is likely that the far-distant triggering of landslides, e.g., by the 1988 Saguenay earthquake (and the related extreme extension of affected area) is partly due to a very low attenuation of seismic energy within the North American plate. This point highlights the need for using region-specific attenuation laws, both for scenario modelling and hazard assessment. Second, far-distant triggering of landslides can be explained by a very high susceptibility of some lithological materials to slope failure, possibly enhanced by strong local amplification of the seismic shaking. According to Rodriguez et al. (1999) and Keefer (2002), both the high susceptibility of weak soils to failure and the local site amplification contributed to far-distant effects of the 1988 Saguenay earthquake. Far-distant triggering of landslides in Central Asia can be explained by the susceptibility of slopes covered by thick soft soils to failure under the effect of low-frequency shaking induced by distant earthquakes, especially by the deep focal earthquakes in the Pamir – Hindukush seismic region. Such deep focal and high magnitude (> > 7) earthquakes are also found in Europe, first of all in the Vrancea region (Romania). For this area as well as for the South Tien Shan marked by a very high seismicity (return period of about 50 years for M > 7 events) we computed worst-case scenarios of earthquake-triggered landslide events. Those results show that several tens of thousands of landslides could be triggered by a single high magnitude earthquake in the South Tien Shan while the number of landslides triggered by a similar large earthquake would be far less (<1000) due to the much deeper hypocentre of events in Vrancea. However, a very strong future earthquake in Vrancea is likely to trigger ground effects over a much larger area, possibly over more than 150,000 km2 and at distances of more than 500 km away from the epicentre.

References

Anagnostopoulos, S.A., D. Rinaldis, V.A. Lekidis, V.N. Margaris, and N.P. Theodulidis. 1987. The Kalamata, Greece, Earthquake of September 13, 1986. Earthquake Spectra 3(2): 365–402.

Angelova, D. 2003. Influence of the Vrancea earthquake from 04 03 1997 on terrains with established paleoseismic events in Bulgaria (preliminary data). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Earthquake Loss Estimation and Risk reduction, Oct. 24–26 2002, Bucharest, Romania, 303–309, ed. D. Lungu et al.

Arboleda, R.A., and R.S. Punongbayan. 1991. Landslides induced by the 16 July 1990 Luzon, Philippines, earthquake. Landslide News 5: 5–7.

Archuleta, R.J., E. Cranswick, C. Mueller, and P. Spudich. 1982. Source parameters of the 1980 Mammoth Lakes, California, earthquake sequence. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 87(B6): 4595–4607.

Azzaro, R., M.S. Barbano, R. Camassi, S.D. Amico, A. Mostaccio, G. Piangiamore, and L. Scarf. 2004. The earthquake of 6 September 2002 and the seismic history of Palermo (Northern Sicily, Italy): Implications for the seismic hazard assessment of the city. Journal of Seismology 8: 525–543.

Bakun, W.H. 1972. Focal depths of the 1966 Parkfield, California, earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research 77(20): 3816–3822.

Bakun, W.H., and M.G. Hopper. 2004. Magnitudes and locations of the 1811–1812 New Madrid, Missouri, and the 1886 Charleston, South Carolina, earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 94(1): 64–75.

Bălteanu, D., C. Embleton, and C. Embleton-Hamman. 1997. Romania. In Geomorphological Hazards of Europe, 409–427. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Barrientos, S.E., R.S. Stein, and S.N. Ward. 1987. Comparison of the 1959 Hebgen Lake, Montana and the 1983 Borah Peak, Idaho, earthquakes from geodetic observations. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 77(3): 784–808.

Beck, S.L., and L.J. Ruff. 1989. Great earthquakes and subduction along the Peru trench. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 57(3–4): 199–224.

Bernard, P., and A. Zollo. 1989. The Irpinia (Italy) 1980 earthquake: detailed analysis of a complex normal faulting. Journal of Geophysical Research 94(B2): 1631–1647.

Bozzano, F., S. Martino, G. Naso, A. Prestininzi, R.W. Romeo, and G.S. Mugnozza. 2004. The Large Salcito Landslide Triggered by the 2002 Molise, Italy, Earthquake. Earthquake Spectra 20(S1): 95–105.

Cheloni, D., R. Giuliani, E. D’Anastasio, S. Atzori, R.J. Walters, L. Bonci, N. D’Agostino, M. Mattone, S. Calcaterra, P. Gambino, F. Deninno, R. Maseroli, and G. Stefanelli. 2014. Coseismic and post-seismic slip of the 2009 L’Aquila (central Italy) MW 6.3 earthquake and implications for seismic potential along the Campotosto fault from joint inversion of high-precision levelling, InSAR and GPS data. Tectonophysics 622: 168–185.

Chen, X.L., L. Yu, M.M. Wang, C.X. Lin, C.G. Liu, and J.Y. Li. 2014. Brief Communication: Landslides triggered by the Ms = 7.0 Lushan earthquake, China. Natural Hazards Earth System Science 14: 1257–1267.

Chleborad, A.F., and R.L. Schuster. 1990. Ground failure associated with the Puget Sound region earthquakes of April 13, 1949, and April 29, 1965, USGS - Open-File Report.

Cirella A., A. Piatanesi, E. Tinti, and M Cocco. 2008. Rupture process of the 2007 Niigata-ken Chuetsu-oki earthquake by non-linear joint inversion of strong motion and GPS data. Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (16)

Collins, B.D., and R.W. Jibson. 2015. Assessment of existing and potential landslide hazards resulting from the April 25, 2015 Gorkha, Nepal earthquake sequence. USGS Open-File Report 2015–1142.. doi:10.3133/ofr20151142.

Collins, B.D., R. Kayen, and Y. Tanaka. 2012. Spatial distribution of landslides triggered from the 2007 Niigata Chuetsu–Oki Japan Earthquake. Engineering Geology 127: 14–26.

Constantin, A.P., A. Pantea, and R. Stoica. 2011. Vrancea (Romania) subcrustal earthquakes: historical sources and macroseismic intensity assessment. Romanian Journal of Physics 56(5–6): 813–826.

Danneels, G., C. Bourdeau, I. Torgoev, and H.-B. Havenith. 2008. Geophysical investigation and numerical modelling of unstable slopes: case-study of Kainama (Kyrgyzstan). Geophysics of Journal International 175: 17–34.

Delgado, J., J. Garrido, C. López-Casado, S. Martino, and J.A. Peláez. 2011. On far field occurrence of seismically induced landslides. Engineering Geology 123(3): 204–213.

Delvaux, D., K.E. Abdrakhmatov, I.N. Lemzin, and A.L. Strom. 2001. Landslide and surface breaks of the 1911 M 8.2 Kemin Earthquake. Landslides 42(10): 1583–1592.

Derbyshire, E., X.M. Meng, and T.A. Dijkstra. 2000. Landslides in the thick loess terrain of north-west China. Chichester: John Wiley.

Dimate, C., L. Rivera, A. Taboada, B. Delouis, A. Osorio, E. Jimenez, A. Fuenzalida, A. Cisternas, and I. Gómez. 2003. The 19 January 1995 Tauramena (Colombia) earthquake: geometry and stress regime. Tectonophysics 363(3): 159–180.

Dunning, S.A., W.A. Mitchell, N.J. Rosser, and D.N. Petley. 2007. The Hattian Bala rock avalanche and associated landslides triggered by the Kashmir Earthquake on October 2005. Engineering Geology 93(3–4): 130–144.

Eberhart-Phillips, D., P.J. Haeussler, J.T. Freymueller, A.D. Frankel, C.M. Rubin, P. Craw, N.A. Ratchkovski, G. Anderson, G.A. Carver, A.J. Crone, T.E. Dawson, H. Fletcher, R. Hansen, E.L. Harp, R.A. Harris, D.P. Hill, S. Hreinsdóttir, R.W. Jibson, L.M. Jones, R. Kayen, D.K. Keefer, C.F. Larsen, S.C. Moran, S.F. Personius, G. Plafker, B. Sherrod, K. Sieh, N. Sitar, and W. Wallace. 2003. The 2002 Denali Fault Earthquake, Alaska: a large magnitude, slip-partitioned event. Science 300: 1113–1118.

Erdik, M., O. Yuzugullu, C. Karakoc, C. Yilmaz, and N. Akkas. 1994. March 13, 1992 Erzincan (Turkey) earthquake. In Earthquake Engineering, Tenth World Conference, 7045–7051.

Esposito, E., S. Porfido, A.L. Simonelli, G. Mastrolorenzo, and G. Iaccarino. 2000. Landslides and other surface effects induced by the 1997 Umbria-Marche seismic sequence. Engineering Geology 58(3–4): 353–376.

Evans, S.G., and A.L. Bent. 2004. The Las Colinas landslide, Santa Tecla: A highly destructive flowslide triggered by the January 13, 2001, El Salvador earthquake. Geological Society of America Special Papers 375: 25–38.

Evans, S.G., N.J. Roberts, A. Ischuk, K.B. Delaney, G.S. Morozova, and O. Tutubalina. 2009. Landslides triggered by the 1949 Khait earthquake, Tajikistan, and associated loss of life. Engineering Geology 109(3): 195–212.

Farías M, D. Comte, S. Roecker, D. Carrizo, and M. Pardo. 2011. Crustal extensional faulting triggered by the 2010 Chilean earthquake: The Pichilemu Seismic Sequence. Tectonics. 30(6)

García-Rodríguez, M.J., J.A. Malpica, B. Benito, and M. Díaz. 2008. Susceptibility assessment of earthquake-triggered landslides in El Salvador using logistic regression. Geomorphology 95(3): 172–191.

Garwood, N.C., D.P. Janos, and N. Brokaw. 1979. Earthquake-caused landslides: a major disturbance to tropical forests. Science 205(4410): 997–999.

Georgescu, E.S. 2003. The partial collapse of the Coltzea Tower during the Vrancea earthquake of 14–26 October 1802: the historical warning of long-period ground motions site effects in Bucharest. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Earthquake Loss Estimation and Risk reduction, Oct. 24–26 2002, Bucharest, Romania, ed. D. Lungu, F. Wenzel, P. Mouroux, and I. Tojo, 303–309.

Ghose, S., R.J. Mellors, A.M. Korjenkov, M.W. Hamburger, T.L. Pavlis, G.L. Pavlis, M. Omuraliev, E. Mamyrov, and A.R. Muraliev. 1997. The MS = 7.3 1992 Suusamyr, Kyrgyzstan, earthquake in the Tien Shan: 2. Aftershock focal mechanisms and surface deformation. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 87(1): 23–38.

Goes, S.D.B., A.A. Velasco, S.Y. Schwartz, and T. Lay. 1993. The April 22, 1991, Valle de la Estrella, Costa Rica (Mw-7.7) earthquake and its tectonic implications: a broadband seismic study. Journal of Geophysical Research 98(B5): 8127–8142.

González, F.I., E.N. Bernard, and K. Satake. 1995. The Cape Mendocino Tsunami, 25 April 1992. In Tsunami: Progress in Prediction, Disaster Prevention and Warning SE- 10. Advances in Natural and Technological Hazards Research, ed. Y. Tsuchiya and N. Shuto, 151–158. Netherlands: Springer.

Gorum, T., X. Fan, C.J. van Westen, R. Huang, Q. Xu, C. Tang, and G. Wang. 2011. Distribution pattern of earthquake-induced landslides triggered by the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Geomorphology 133: 152–167.

Gorum, T., C.J. van Westen, O. Korup, M. van der Meijde, X. Fan, and F.D. van der Meer. 2013. Complex rupture mechanism and topography control symmetry of mass-wasting pattern, 2010 Haiti earthquake. Geomorphology 184: 127–138.

Govi, M. 1977. Photo-interpretation and mapping of the landslides triggered by the Friuli earthquake (1976). Bulletin of the International Association of Engineering Geology 15: 67–72.

Harp, E.L., and R.W. Jibson. 1996. Landslides triggered by the 1994 Northridge, California, earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 86(1B): 319–332.

Harp, E.L., and R.C. Wilson. 1995. Shaking intensity thresholds for rock falls and slides: evidence from 1987 Whittier Narrows and Superstition Hills earthquake strong-motion records. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 85(6): 1739–1757.

Harp, E.L., D.K. Keefer, and R.C. Wilson. 1980. A comparison of artificial and natural slope failures; the Santa Barbara earthquake of August 13, 1978. California Geology 33(5): 102–105.

Harp, E.L., R.C. Wilson, and G.F. Wieczorek. 1981. Landslides from the February 4, 1976, Guatemala earthquake, USGS professional paper 1204-A.

Havenith, H.-B., and C. Bourdeau. 2010. Earthquake-induced hazards in mountain regions: a review of case histories from Central Asia. Geologica Belgica 13: 135–150.

Havenith, H.-B., D. Jongmans, E. Faccioli, K. Abdrakhmatov, and P.Y. Bard. 2002. Site effect analysis around the seismically induced Ananevo Rockslide, Kyrgyzstan. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 92: 3190–3209.

Havenith, H.B., K. Abdrakhmatov, I. Torgoev, A. Ischuk, A. Strom, E. Bystrický, and A. Cipciar. 2013. Earthquakes, landslides, dams and reservoirs in the Tien Shan, Central Asia. In 2nd World Landslide Forum, WLF 2011, Rome, Italy; published in ‘Landslide Science and Practice: Risk Assessment, Management and Mitigation’, vol. 6, ed. C. Margottini, 27–31. Rome: Springer.

Havenith, H.-B., A. Strom, I. Torgoev, A. Torgoev, L. Lamair, A. Ischuk, and K. Abdrakhmatov. 2015a. Tien Shan geohazards database: Earthquakes and landslides. Geomorphology 249: 16–31.

Havenith, H.B., A. Torgoev, R. Schlögel, A. Braun, I. Torgoev, and A. Ischuk. 2015b. Tien Shan geohazards database: Landslide susceptibility analysis. Geomorphology 249: 32–43.

Hermanns, R., S. Sepúlveda, G. Lastras, D. Amblas, M. Canals, M. Azpiroz, I. Bascuñán, A. Calafat, P. Duhart, J. Frigola, O. Iglesias, P. Kempf, S. Lafuerza, O. Longva, A. Micallef, T. Oppikofer, X. Rayo, G. Vargas, F. Molina, et al. 2014. Earthquake-Triggered Subaerial Landslides that Caused Large Scale Fjord Sediment Deformation: Combined Subaerial and Submarine Studies of the 2007 Aysén Fjord Event, Chile. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory - Volume 4 SE - 14, ed. G. Lollino, 67–70. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Hicks, S.P., and A. Rietbrock. 2015. Seismic slip on an upper-plate normal fault during a large subduction megathrust rupture. Nature Geoscience 8(12): 955–960.

Huang, R., and X. Fan. 2013. The landslide story. Nature Geoscience 6: 325–326.

Ichinose, G.A., H.K. Thio, and P.G. Somerville. 2004. Rupture process and near-source shaking of the 1965 Seattle-Tacoma and 2001 Nisqually, intraslab earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters; 31(10)

Ichinose, G., P. Somerville, H.K. Thio, R. Graves, and D. O’Connell. 2007. Rupture process of the 1964 Prince William Sound, Alaska, earthquake from the combined inversion of seismic, tsunami, and geodetic data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 112: B07306. doi:10.1029/2006JB004728.

Ishihara, K., S. Okusa, N. Oyagi, and A. Ischuk. 1990. Liquefaction-induced flow slide in the collapsible deposit in the Soviet Tajik. Soils and Foundations 30: 73–89.

Jacques, E., C. Monaco, P. Tapponnier, L. Tortorici, and T. Winter. 2001. Faulting and earthquake triggering during the 1783 Calabria seismic sequence. Geophysical Journal International 147: 499–516.

Jennings, P.C., and G.W. Housner. 1973. The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971. In Proceedings of the Fifth. Rome: World Conference on Earthquake Engineering.

Jibson, R.W. 1996. Use of landslides for paleoseismic analysis. Engineering Geology 43(4): 291–323.

Jibson, R.W., and E.L. Harp. 2012. Extraordinary distance limits of landslides triggered by the 2011 Mineral, Virginia, earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 102(6): 2368–2377.

Jibson, R.W., C.S. Prentice, B.A. Borissoff, E.A. Rogozhin, and C.J. Langer. 1994. Some observations of landslides triggered by the 29 April 1991 Racha earthquake, Republic of Georgia. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 84(4): 963–973.

Jibson, R.W., E.L. Harp, W. Schulz, and D.K. Keefer. 2006. Large rock avalanches triggered by the M 7.9 Denali Fault, Alaska, earthquake of 3 November 2002. Engineering geology 83: 144–160.

Keefer, D.K. 1984. Landslides caused by earthquakes. Geological Society of America Bulletin 95(4): 406–421.

Keefer, D.K. 1998. The Loma Prieta, California, Earthquake of October 17, 1989 – Landslides. USGS professional paper 1551-C.

Keefer, D.K. 2002. Investigating landslides caused by earthquakes – a historical review. Surveys in Geophysics 23(6): 473–510.

Keefer, D.K., and R.C. Wilson. 1989. Predicting earthquake-induced landslides, with emphasis on arid and semi-arid environments. In Landslides in a semi-arid environment with emphasis on the Inland Valleys of Southern California, ed. P.M. Sadler and D.M. Morton, 118–149. Riverside: Inland Geological Society of Southern California Publications. v. 2, part 1.

Keefer, D.K., R.C. Wilson, E.L. Harp, and E.W. Lips. 1985. The Borah Peak, Idaho Earthquake of October 28, 1983—Landslides. Earthquake Spectra 2(1): 91–125.

Keefer, D.K., J. Wartman, C. Navarro Ochoa, A. Rodriguez-Marek, and G.F. Wieczorek. 2006. Landslides caused by the M 7.6 Tecomán, Mexico earthquake of January 21, 2003. Engineering Geology 86(2–3): 183–197.

Khazai, B., and N. Sitar. 2003. Evaluation of factors controlling earthquake-induced landslides caused by Chi-Chi Earthquake and comparison with the Northridge and Loma Prieta events. Engineering Geology 71(1–2): 79–95.

Kieffer, D.S., R. Jibson, E.M. Rathje, and K. Kelson. 2006. Landslides triggered by the 2004 Niigata Ken Chuetsu, Japan, earthquake. Earthquake Spectra 22(S1): 47–73.

King, N.E., and W. Thatcher. 1998. The coseismic slip distributions of the 1940 and 1979 Imperial Valley, California, earthquakes and their implications. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 103(B8): 18069–18086.

Kingdon-Ward, F. 1955. Aftermath of the Assam earthquake of 1950. Geographical Journal 121(3): 290–303.

Koketsu, K., Y. Yokota, N. Nishimura, Y. Yagi, S.I. Miyazaki, K. Satake, Y. Fujii, H. Miyake, S. Sakai, Y. Yamanaka, and T. Okada. 2011. A unified source model for the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 310(3): 480–487.

Langer, C.J., and S. Hartzell. 1996. Rupture distribution of the 1977 western Argentina earthquake. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 94(1–2): 121–132.

Lazaridou-Varotsos, M. 2013. Disastrous earthquakes in Killini-Vartholomio, 1988. In Earthquake Prediction by Seismic Electric Signals SE - 6, 59–66. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Praxis Books.

Lei, C.I. 2012. Earthquake-triggered landslides. Proc. 1st Civil and Environmental Engineering Student Conference, 25–26 June 2012, 6. London: Imperial College.

Li, W., R. Huang, X. Pei, and X. Zhang. 2015. Historical Co-seismic Landslides Inventory and Analysis Using Google Earth: A Case Study of 1920 M8.5 Haiyuan Earthquake, China. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory, vol. 2, ed. G. Lollino, 709–712.

Lin, Y.N., A. Sladen, F. Ortega-Culaciati, M. Simons, J.-P. Avouac, E.J. Fielding, B.A. Brooks, M. Bevis, J. Genrich, A. Rietbrock, C. Vigny, R. Smalley, and A. Socquet. 2013. Coseismic and postseismic slip associated with the 2010 Maule Earthquake, Chile: Characterizing the Arauco Peninsula barrier effect. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 118(6): 3142–3159.

Lunina, O.V., A.S. Gladkov, I.S. Novikov, A.R. Agatova, E.M. Vysotskii, and A.A. Emanov. 2008. Geometry of the fault zone of the 2003 Ms = 7.5 Chuya earthquake and associated stress fields, Gorny Altai. Tectonophysics 453(1): 276–294.

Mândrescu, N. 1981. The Romanian earthquake of March 4, 1977: aspects of soil behaviour. Revenue Romanian Geology Geophysics et Geographic. – Geophysique 25: 35–56.

Martinez, J.M., R.L. Schuster, T.J. Casadevall, and K.M. Scott. 1995. Landslides and debris flows triggered by the 6 June 1994 Paez earthquake, southwestern Colombia. Landslide News 9: 13–15.

Martino, S., A. Prestininzi, and R. Romeo. 2014. Earthquake-induced ground failures in Italy. Natural Hazards and Earth System Science 14: 799–814.

Mathews, W.H. 1979. Landslides of central Vancouver Island and the 1946 earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 69(2): 445–450.

Mathur, L.P. 1953. Assam earthquake of 15th Aug., 1950-a short note on factual observations. The Central Board of Geophysics 1: 56–60.

Mavko, G.M., S. Schulz, and B.D. Brown. 1985. Effects of the 1983 Coalinga, California, earthquake on creep along the San Andreas fault. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 75(2): 475–489.

Mellors, R.J., F.L. Vernon, G.L. Pavlis, G.A. Abers, M.W. Hamburger, S. Ghose, and B. Iliasov. 1997. The Ms = 7.3 1992 Suusamyr, Kyrgyzstan, earthquake: 1. Constraints on fault geometry and source parameters based on aftershocks and body-wave modeling. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 87(1): 11–22.

Meunier, P., N. Hovius, and J.A. Haines. 2008. Topographic site effects and the location of earthquake induced landslides. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 275: 221–232.

Mikoš, M., M. Jemec, M. Ribičič, M. Čarman, and M. Komac. 2013. Earthquake-Induced Landslides in Slovenia: Historical Evidence and Present Analyses. In Earthquake-Induced Landslides SE - 23, ed. K. Ugai, H. Yagi, and A. Wakai, 225–233. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Miller, D.J. 1960. The Alaska earthquake of July 10, 1958: Giant wave in Lituya Bay. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 50(2): 253–266.

Monaco, C., S. Mazzoli, and L. Tortorici. 1996. Active thrust tectonics in western Sicily (southern Italy): the 1968 Belice earthquake sequence. Terra Nova 8(4): 372–381.

Mosquera-Machado, S., C. Lalinde-Pulido, E. Salcedo-Hurtado, and A.M. Michetti. 2009. Ground effects of the 18 October 1992, Murindo earthquake (NW Colombia), using the Environmental Seismic Intensity Scale (ESI 2007) for the assessment of intensity. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 316(1): 123–144.

Niyazov, R.A., and B.S. Nurtaev. 2010. Landslides of liquefaction, caused by the joint influence of rainfall and long distant earthquakes. In: Problems of Seismology in Uzbekistan, Volume II, 29–54. Tashkent

Niyazov, R.A., and B.S. Nurtaev. 2013. Modern seismogenic landslides caused by the Pamir-Hindukush earthquakes and their consequences in Central Asia. In Landslide science and practice, vol. 5, ed. C. Margottini et al., 343–348. Heidelberg: Springer.

Niyazov, R., and B. Nurtaev. 2014. Landslides of liquefaction caused by single source of impact Pamir-Hindukush earthquakes in Central Asia. In Landslide Science for a Safer Geoenvironment, ed. K. Sassa, P. Canuti, and Y. Yin, 225–232. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Ohta, Y., M. Ohzono, S. Miura, T. Iinuma, K. Tachibana, K. Takatsuka, K. Miyao, T. Sato, and N. Umino. 2008. Coseismic fault model of the 2008 Iwate-Miyagi Nairiku earthquake deduced by a dense GPS network. Earth Planets and Space 60(12): 1197–1201.

Papadopoulos, G.A., V.K. Karastathis, A. Ganas, S. Pavlides, A. Fokaefs, and K. Orfanogiannaki. 2003. The Lefkada, Ionian Sea (Greece), shock (Mw 6.2) of 14 August 2003: Evidence for the characteristic earthquake from seismicity and ground failures. Earth Planets and Space 55(11): 713–718.

Petley, D. 2015. Landslides from the Afghanistan earthquake on Monday, blog post from 28 October 2015 on “The Landslide Blog”.. http://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2015/10/28/afghanistan-earthquake-1/.

Petley, D., S. Dunning, N. Rosser, and A.B. Kausar. 2006. Incipient Landslides in the Jhelum Valley, Pakistan Following the 8th October 2005 Earthquake. In Disaster Mitigation of Debris Flows, Slope Failures and Landslides, 47–55. Tokyo: Universal Academy Press Inc.

Plafker, G.L., and A. Gajardo. 1985. Geologic reconnaissance of the March 3, 1985, Chile earthquake. US Geology Survey 85(0542): 13–20. Open File Report.

Ponce, L., J. Rodríguez, J. Domínguez, W. Montero, W. Rojas, I. Boschini, G. Suárez, E. Camacho. 2010. Estudio de réplicas del Terremoto de Limón usando datos locales: resultados e implicaciones tectónicas. Revista Geológica de América Central, 103–110

Qamar, A. 1995. The 1993 Klamath Falls, Oregon, earthquake sequence: Source mechanisms from regional data. Geophysical Research Letters 22(2): 105–108.

Radu, C., and E. Spânoche. 1977. On geological Phenomena associated with the 10 November 1940 earthquake. Revenue Romanian Geology Geophysics et Geographic. – Geophysique 21: 159–165.

Rodrıguez, C.E., J.J. Bommer, and R.J. Chandler. 1999. Earthquake-induced landslides: 1980–1997. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 18(5): 325–346.

Rogozhin, E.A., A.N. Ovsyuchenko, A.R. Geodakov, and S.G. Platonova. 2003. A strong earthquake of 2003 in Gornyi Altai. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences 5(6): 439–454.

Rymer, M.J. 1987. The San Salvador Earthquake of October 10, 1986-Geologic Aspects. Earthquake Spectra 3(3): 435–463.

Schuster, R.L., A.S. Nieto, T.D. O’Rourke, E. Crespo, and G. Plaza-Nieto. 1996. Mass wasting triggered by the 5 March 1987 Ecuador earthquakes. Engineering geology 42(1): 1–23.

Shen, L., C. Xu, and L. Liu. 2015. Interaction among controlling factors for landslides triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan, China Mw 7.9 earthquake. Frontiers of Earth Sciences 10: 264–273.

Shoaei, Z., and K. Sassa. 1993. Mechanism of landslides triggered by the 1990 Iran earthquake. Bulletin of the Disasters Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University 372(1): 1–29.

Shreve, R.L. 1966. Sherman landslide, Alaska. Science 154(3757): 1639–1643.

Stein, R.S., and M. Lisowski. 1983. The 1979 Homestead Valley earthquake sequence, California; control of aftershocks and postseismic deformation. Journal of Geophysical Research 88(B8): 6477–6490.

Syvitski, J.P.M., and C.T. Schafer. 1996. Evidence for an earthquake-triggered basin collapse in Saguenay Fjord, Canada. Sedimentary Geology 104(1): 127–153.

Tatard, L., and J.R. Grasso. 2013. Controls of earthquake faulting style on near field landslide triggering: The role of coseismic slip. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 118(6): 2953–2964.

Tavera, H., I. Bernal, F.O. Strasser, M.C. Arango-Gaviria, J.E. Alarcón, and J.J. Bommer. 2009. Ground motions observed during the 15 August 2007 Pisco, Peru, earthquake. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 7(1): 71–111.

Theilen-Willige, B. 2010. Detection of local site conditions influencing earthquake shaking and secondary effects in Southwest-Haiti using remote sensing and GIS-methods. Natural Hazards and Earth System Science 10(6): 1183–1196.

Torgoev, I., R. Niyazov, and H.-B. Havenith. 2013. Tien-Shan landslides triggered by earthquakes in Pamir-Hindukush zone. In Landslide science and Practice, ed. C. Margottini, P. Canuti, and K. Sassa, 191–197. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

Tranfaglia, G., E. Esposito, S. Porfido, and R. Pece. 2011. The 23 July 1930 earthquake (Ms = 6.7) in the Southern Apennines (Italy): geological and hydrological effects. Bollettino Geofisico 1-4(XXXIV): 63–86.

Umar, Z., B. Pradhan, A. Ahmad, M.N. Jebur, and M.S. Tehrany. 2014. Earthquake induced landslide susceptibility mapping using an integrated ensemble frequency ratio and logistic regression models in West Sumatera Province, Indonesia. Catena 118: 124–135.

USGS, 2015. M7.2 - 105km W of Murghob, Tajikistan. Online data: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us100044k6#general_summary

USGS, 2015. M7.5 - 45km E of Farkhar, Afghanistan. Online data: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us10003re5#general_summary

Valkaniotis, S., A. Ganas, G. Papathanassiou, and M. Papanikolaou. 2014. Field observations of geological effects triggered by the January-February 2014 Cephalonia (Ionian Sea, Greece) earthquakes. Tectonophysics 630: 150–157.

Velasco, A.A., C.J. Ammon, T. Lay, and M. Hagerty. 1996. Rupture process of the 1990 Luzon, Philippines (Mw = 7.7), earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth (1978–2012) 101(B10): 22419–22434.

Wartman, J., L. Dunham, B. Tiwari, and D. Pradel. 2013. Landslides in eastern Honshu induced by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 103(2B): 1503–1521.

Weischet, W. 1963. Further observations of geologic and geomorphic changes resulting from the catastrophic earthquake of May 1960, in Chile. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 53(6): 1237–1257.

Wilson, R.C., and D.K. Keefer. 1983. Dynamic analysis of a slope failure from the 6 August 1979 Coyote Lake, California, earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 73(3): 863–877.

Yagi, H., G. Sato, D. Higaki, M. Yamamoto, and T. Yamasaki. 2009. Distribution and characteristics of landslides induced by the Iwate–Miyagi Nairiku Earthquake in 2008 in Tohoku District, Northeast Japan. Landslides 6(4): 335–344.

Yeats, R.S., and C. Madden. 2003. Damage from the Nahrin, Afghanistan, earthquake of 25 March 2002. Seismological Research Letters 74(3): 305–311.

Youd, T.L., and S.N. Hoose. 1978. Historic ground failures in northern California triggered by earthquakes, U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

Zhang, Z. 1995. Geological Disasters in Loess Areas during the 1920 Haiyuan Earthquake. GeoJournal 36.2(3): 269–274.

Zhang, D., and G. Wang. 2007. Study of the 1920 Haiyuan earthquake-induced landslides in loess (China). Engineering Geology 94: 76–88.

Zoback, M.L., R.C. Jachens, and J.A. Olson. 1999. Abrupt along-strike change in tectonic style: San Andreas Fault zone, San Francisco Peninsula. Journal of Geophysical Research. 104(B5)

Acknowledgements

We thank Anatoly Ischuk and Alexander Strom for some data inputs and comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the database construction and analysis; all read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Havenith, HB., Torgoev, A., Braun, A. et al. A new classification of earthquake-induced landslide event sizes based on seismotectonic, topographic, climatic and geologic factors. Geoenviron Disasters 3, 6 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-016-0041-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-016-0041-1