Abstract

Background

Gut microbiota play crucial roles in host health. Wild birds and domestic poultry often occupy sympatric habitats, which facilitate the mutual transmission of intestinal microbes. However, the distinct intestinal microbial communities between sympatric wild birds and poultry remain unknown. At present, the risk of interspecies transmission of pathogenic bacteria between wild and domestic host birds is also a research hotspot.

Methods

This study compared the intestinal bacterial communities of the overwintering Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) and the Domestic Goose (Anser anser domesticus) at Shengjin Lake, China, using Illumina high-throughput sequencing technology (Mi-Seq platform).

Results

Our results revealed that Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi were the dominant bacterial phyla in both hosts. The gut bacterial community composition differed significantly between sympatric Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. However, the hosts exhibited little variation in gut bacterial alpha-diversity. The relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly higher in the guts of the Hooded Cranes, while the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidete and Chloroflexi were significantly higher in guts of Domestic Geese. Moreover, a total of 132 potential pathogenic operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were detected in guts of Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese, and 13 pathogenic OTUs (9.8%) were found in both host guts. Pathogenic bacterial community composition and diversity differed significantly between hosts.

Conclusions

The results showed that the gut bacterial community composition differs significantly between sympatric Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. In addition, potential pathogens were detected in the guts of both Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese, with 13 pathogenic OTUs overlapping between the two hosts, suggesting that more attention should be paid to wild birds and poultry that might increase the risk of disease transmission in conspecifics and other mixed species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gut microbes affect the health of their host in terms of metabolism, immunity, and digestion (Grond et al. 2018). Vertebrate studies suggest that environmental (i.e., geography, diet) and behavioral (i.e., social contact patterns) factors may influence the structure of the host gut microbiome (Hird et al. 2014; Xiong et al. 2015; Nejrup et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2019). Studies of gut microbiomes in sympatric mammals have shown that the sympatric environment can affect the different host gut microbiome (Perofsky et al. 2019). Several studies of zoo animals have also claimed that diet and shared environment have greater impacts on gut microbiome composition (Muegge et al. 2011; Sanders et al. 2015). In addition, studies demonstrated that gut microbial communities exhibit strong host specificity and higher similarity among hosts with closer genetic relationships (Fan et al. 2020).

Increased attention has been paid to the gut microbiome of wild birds and poultry because they could be a source of many human and animal diseases through direct transmission or as carriers of zoonotic pathogens (Caron et al. 2010; Waite et al. 2014; Pantin-Jackwood et al. 2016; Ekong et al. 2018). Studies have shown that different hosts could mutually transmit intestinal microbes in a shared environment through physical contact, air, water, soil, food, or other media (Galen and Witt 2014; Grond et al. 2014; Alm et al. 2018). Large numbers of domestic geese and ducks live in the vicinity of overwintering waterbirds, and they commonly forage in the same waters or mudflats (Jourdain et al. 2007). Therefore, the different species can easily spread their microbes to other organisms in a shared environment (Jourdain et al. 2007; Ramey et al. 2010; Reed et al. 2014). Identifying intestinal potential pathogens in wild birds and poultry is helpful for evaluation of their epidemic sources and risk of disease transmission. In addition, it provides an important theoretical basis for protecting wild bird population and preventing poultry disease. Research on intestinal pathogens has recently garnered increased attention (Morgavi et al. 2015). However, most microbiome studies have focused on captive or wild species in differing geographic and ecological environments, with few related studies in the sympatric environment.

Anser anser domestic is the domesticated Grey Goose (Anser anser) and is one of the most common, large-scale, free-range poultry species in China. The Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) as a vulnerable (VU) species in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2020) is a large migratory waterbird that overwinters in Japan, South Korea, and in the middle and lower Yangtze River floodplain in China (Jiao et al. 2014). Plants such as Vallisneria natans and Potamogeton malaianus are the main food resources of the Hooded Crane in the winter (Fox et al. 2011). However, the food resources for Domestic Geese are mainly artificial diets and wild plants. Shengjin Lake is a Ramsar Site and an important overwintering habitat for waterbirds on the East Asian–Australasian flyway (Peng et al. 2018). Hooded Cranes migrated to the middle and lower Yangtze River floodplain each October (Chen et al. 2011). Unfortunately, human activities have degraded the surrounding wetlands, forcing foraging niche overlap between wild and domestic birds, which increased the possibility of shared transmission of intestinal microbiota between wild birds and Domestic Geese (Yang et al. 2015). All of these factors led us to focus on the gut microbes of overwintering Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese.

In this study, we used the high-throughput sequencing method (Illumina Mi-Seq) to analyze the intestinal bacterial communities of wintering Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese at the Shengjin Lake. We characterized the intestinal bacteria between sympatric Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese, and further compared the bacterial communities and inferred the potential pathogens in the guts of the two hosts.

Methods

Ethics statement

To avoid human interference and hunting of experimental animals, faecal samples from Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese were collected in a non-invasive manner. Our study was approved by the Shengjin Lake National Nature Reserve.

Site selection and sample collection

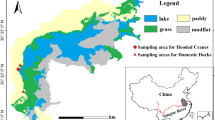

The study area was the upstream of the Shengjin Lake (30° 15ʹ–30° 30ʹ N, 116° 55ʹ–117° 15ʹ E), which lies on the south bank of the Yangtze River in Anhui Province, China (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The study site belongs to the subtropical monsoon climate, and has an average annual rainfall of 1600 mm, with the heaviest precipitation in May and August (Fang et al. 2006).

During December 2017, we observed Hooded Cranes in their winter habitat at Shengjin Lake and a flock of Domestic Geese foraging near the cranes (i.e., around 100 m away) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). After the cranes and Domestic Geese vacated their foraging grounds, we rapidly collected faecal samples in sterile 50 mL centrifuge tubes. To avoid collecting multiple samples from the same birds, the distance between collected specimens was > 5 m. To minimise contamination, we collected only the upper layer of faeces (avoiding the underlying soil, grass, and sand), stored the samples in a shady area, and transported them to the laboratory as soon as possible. Faecal samples were stored at − 80 °C before DNA extraction. Forty faecal samples in this study were obtained from 20 Hooded Crane individuals and 20 Domestic Goose individuals.

Sample pretreatment

Faecal DNA extraction, bird species determination, PCR, and amplicon library preparation are described in the Additional file 2: Supporting Information.

Processing of sequence data

We used Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME 1.90) to process the raw bacterial data (Caporaso et al. 2010). Poor-quality sequences, i.e., those with average quality scores < 30 and sequences < 250 bp in length, were not included in the analysis. High-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with an identity threshold of 97% by UCLUST (Edgar 2010). Chimeras and singleton OTUs were not included in our analysis. The most abundant sequence for each OTU was chosen as the representative sequence. Representative sequences were aligned by PyNAST (Caporaso et al. 2010). We randomly selected subsets of 25,000 sequences (the lowest sequence read depth: 20 repetitions) of equally rarefied samples. Each sample was used to compare bacterial community composition and diversity with all other samples.

Potentially pathogenic species determination

All bacterial species identified were searched in the Web of Science database. Species referenced as potentially pathogenic in humans or other animals were sorted for further research. Bacillus cereus (Bottone 2010), Rothia dentocariosa (Ferraz et al. 1998), Porphyromonas endodontalis (Murakami et al. 2001), Actinomyces europaeus (Nielsen 2015), Grimontia hollisae (Curtis et al. 2007), Eggerthella lenta (Venugopal et al. 2012), Micrococcus luteus (Erbasan 2018), Capnocytophaga ochracea (Desai et al. 2007), Helicobacter pylori (Kira and Isobe 2019), Rhodococcus ruber (Lalitha et al. 2006), and Treponema socranskii (Lee et al. 2006) are mainly human pathogens. Fishes are the primary hosts for Flavobacterium columnare, Vagococcus salmoninarum, and Piscirickettsia salmonis (Smith et al. 1999; LaFrentz et al. 2018). Mucispirillum schaedleri may cause disease in mice (Loy et al. 2017). Brevibacillus laterosporus infects invertebrates (Ruiu 2013). Enterococcus casseliflavus may be pathogenic in humans and horses (Nocera et al. 2017). Prevotella copri may cause disease in humans and mice (Scher 2013). Mycobacterium celatum (Pate et al. 2011), Arcobacter cryaerophilus (Hsueh et al. 1997) and Staphylococcus sciuri (Chen et al. 2007) may infect humans and pigs. Vermamoeba vermiformis is a potential pathogen in humans and fishes (Scheid et al. 2019). Macrococcus caseolyticus could cause mice disease (Li et al. 2018). Pasteurella multocida may cause human and cattle infections (Zhu et al. 2019). Clostridium perfringens may cause infections in humans, birds, pigs, and other animals (Craven et al. 2000). Enterococcus cecorum may be pathogenic to humans, chickens, birds, and other animals (Delaunay et al. 2015; Jung et al. 2018). Lactococcus garvieae is primarily pathogenic to humans, fishes, and cattles (Vendrell et al. 2006) (Additional file 3: Table S1).

Statistical analysis

To analyse differences in intestinal bacterial taxa among host species linear discriminan analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was carried out, which uses the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test with default settings to determine biomarkers (Segata et al. 2011). Most statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Development Core Team 2006). Community compositions and potential differences between host species were analysed using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and analysis of similarity (ANOSIM; permutations = 999) with the vegan package in R (Version 2.0-2; Oksanen et al. 2010). Bacterial alpha-diversity differences and the relative abundance of potentially pathogenic intestinal species with normal distribution were examined using one-way ANOVA (Additional file 3: Table S2). Indicator analysis was used to identify indicator taxa associated with each group evaluated (Dufrêne and Legendre 1997). Contributions of each bacterial OTU to the total difference between intestinal bacterial communities of the Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese were analysed with the SIMPER analysis routine. The Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test was used to analyse the relative abundance of potentially pathogenic species with non-normal distribution.

Results

Intestinal bacterial community composition

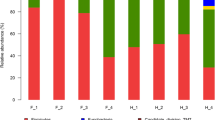

Firmicutes (63.49%), Actinobacteria (22.41%), Proteobacteria (8.19%), Bacteroidete (1.56%), and Chloroflexi (1.22%) were the dominant intestinal bacterial phyla in the guts of both hosts. The relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly higher in the gut of Hooded Cranes, while the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidete, and Chloroflexi were significantly higher in the gut of Domestic Geese (Fig. 1). In addition, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes was significantly higher in the gut of Hooded Cranes than that of Domestic Geese (Fig. 1). The LEfSe analysis revealed that 8 bacterial phyla (i.e., Crenarchaeota, Chlamydiae, Cyanobacteria, etc.) and 17 bacterial classes (i.e., Aigarchaeota, Methanobacteria, Methanomicrobia, etc.) were significantly more abundant in the samples of Hooded Cranes than in Domestic Geese (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Fig. S3). The bacteria from 7 phyla (i.e., Parvarchaeota, Actinobacteria, Armatimonadetes, etc.) and 16 classes (i.e., Thermococci, Parvarchaea, Armatimonadia, etc.) were significantly abundant in the Domestic Geese (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Indicator analysis identified 19 OTUs, 7 and 12 of which were from the Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese respectively. OTU 41326 (Lactobacillus) was the most abundant indicator in the gut of Hooded Cranes with relative abundance of 13.94%. The most abundant indicator in the gut of Domestic Geese was OTU 40439 (Nocardia) with relative abundance of 13.16% (Additional file 3: Table S4). The gut bacterial community composition differed significantly between Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese (ANOSIM: P = 0.001) (Fig. 3). Variations in the abundance of Lactobacillus (14.48%) and Nocardia (10.69%) were primarily responsible for the major discrepancy of bacterial community composition between the two species (Table 1).

LEfSe analysis of intestinal bacterial biomarkers associated with host types. Identified phylotype biomarkers were ranked by effect size and the alpha value was < 0.05. Each filled circle represents one biomarker. Cladogram represents the taxonomic hierarchical structure of the phylotype biomarkers identified between two host types; red, phylotypes overrepresented in gut of Hooded Cranes; green, phylotypes statistically overrepresented in gut of Domestic Geese; yellow, phylotypes for which relative abundance is not significantly different between the two host types. HC: Hooded Crane, DG: Domestic Goose

Intestinal bacterial alpha-diversity

A total of 1,573,478 quality-filtered bacterial sequences were found, ranging from 25,936 to 58,312 sequences per sample (Additional file 3: Table S3). We identified 27,316 bacterial OTUs, ranging from 1002 to 4825 across all samples (97% similarity), 10.7% of which (2904) were found in both species. We found 12,698 (46.8%) and 11,534 (42.5%) unique bacterial OTUs for the Hooded Crane and the Domestic Goose, respectively. One-way ANOVA revealed little difference between the gut bacterial alpha-diversity of the two hosts (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

Intestinal potential pathogenic bacteria

We identified 27 potential pathogenic species in the guts of Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. The C. perfringens was the dominant potential pathogenic species in guts of both hosts, which may cause disease in humans, birds, pigs and others animals (Additional file 3: Table S1). Compared with Domestic Geese, the gut of Hooded Cranes contained higher relative abundances of C. perfringens and V. vermiformis. However, the potential pathogenic species M. caseolyticus, E. casseliflavus, E. cecorum, B. cereus, A. cryaerophilus, R. dentocariosa, L. garvieae, M. luteus, R. ruber, and S. sciuri were significantly abundant in the Domestic Geese relative to Hooded Cranes (Table 2). The composition of pathogenic bacterial community differed significantly between the guts of Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese (ANOSIM, P = 0.001) (Fig. 4a).

We identified 1275 (0.081% relative to all bacterial reads) potential pathogenic sequences with sequence ranges from 5 to 94 per sample (Additional file 3: Table S3). Most of the potentially pathogenic sequences were found in the intestines of the Hooded Crane. A total of 132 potential pathogenic OTUs were identified, 9.8% of which overlapped between the two hosts (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). Potential pathogenic OTU richness was remarkably higher in Domestic Geese than Hooded Cranes (P = 0.04, Mann–Whitney test) (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

Our study revealed significant differences in the gut bacterial community composition of the Hooded Crane and the Domestic Goose. However, little alpha-diversity variation was found between the hosts. Avian studies have demonstrated that host genetic factors are the main influencing factors of their gut microbiota (Zhao et al. 2013; Waite et al. 2014; Xiang et al. 2019). Local food resources also affect the colonisation of host gut microbiota (Grond et al. 2017). Studies on poultry have identified different dietary effects on establishment of the host gut microbiota (Wise and Siragusa 2007; Muegge et al. 2011; Stanley et al. 2012, 2014). Although the Hooded Cranes and free-range Domestic Geese forage in the same waters, geese also ingest artificial fodder as a supplemental food. In this study, we found significant differences in the gut microbiota community structure between the Hooded Crane and Domestic Goose, and we thus speculate that both host genetic factors and diet may led to the divergence in gut bacterial community composition between two hosts.

The dominant phyla of the gut microbiota were Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Chloroflexi in both host species. This result is consistent with a previous study of vertebrate gut microbiota (Deng and Swanson 2015). The most prevalent intestinal bacterial phylum was Firmicutes in both hosts, which concurs with previous avian studies conducted in seabirds (Lan et al. 2002), penguins (Dewar et al. 2013), and turkeys (Wilkinson et al. 2017). Firmicutes plays a key role in degradation of fiber (Flint et al. 2008) into volatile fatty acids that provide energy for the hosts (Flint et al. 2008). The Hooded Cranes exhibited higher relative abundance of Firmicutes than Domestic Geese. Hooded Cranes mainly feed on grass roots with high fiber content in the harsh winter environment, suggesting that wild birds might rely more on their gut microbiota to improve digestion and absorption of nutrients.

Bacteroides and Proteobacteria are associated with polysaccharide and protein breakdown (Spence et al. 2006; Chevalier et al. 2015; Speirs et al. 2019). The diet of Domestic Geese consists of wild plants and artificial fodder. However, the protein and polysaccharide content of artificial fodder is relatively high, which may lead to the higher abundance of Bacteroides and Proteobacteria in guts of the Domestic Goose relative to the Hooded Crane.

In this study, we found that 9.8% of pathogenic OTUs were found in the guts of both Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). The composition and diversity of potential pathogens communities varied significantly between hosts (Fig. 4). Hooded Cranes exhibited less potential pathogen diversity and a higher Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio than Domestic Geese. Our results are consistent with a previous study that an elevated Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio significantly inhibited intestinal pathogens (He et al. 2019). These results suggest that the Domestic Goose may be at higher risk of disease than the Hooded Crane.

The most abundant potential pathogen in the Hooded Cranes was Clostridium perfringens (Table 2). Previous studies demonstrated that C. perfringens can cause diseases such as tissue necrosis bacteremia in humans or birds (Bortoluzzi et al. 2019; Koziel et al. 2019). Rhodococcus ruber was the most abundant in the Domestic Goose, which may cause keratitis in humans (Lalitha et al. 2006). Previous studies indicated that cross-infection by pathogenic bacteria is possible between sympatric migratory birds and poultry (Grond et al. 2014; Pantin-Jackwood et al. 2016; Xiang et al. 2019). Our results also suggest that the shared environment may play an important role in the cross-transmission of pathogenic microorganisms, which may cause periodic outbreaks and cyclical infections between sympatric Domestic Geese and migratory birds.

We identified five potential pathogens that may cause serious disease in fishes, and four potential pathogens that may cause porcine disease (Additional file 3: Table S1). The Shengjin Lake is a crucial habitat for poultry, livestock, and also a fishery area. Pathogens in the faeces of Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese could easily contaminate water, air and soil. We also identified several bacteria that are potential pathogens to humans and/or other animals (Additional file 3: Table S1). Overall, the results suggest that more attention should be paid to the potential pathogens of wild birds and poultry to prevent disease transmission in conspecifics and other mixed species.

There were certain limitations in this study. Only two species with 20 replicates were selected for study. Moreover, the factor of distance between the poultry and wild birds is not considered in intestinal bacterial comparison. Finally, we did not evaluate the potential impact of time and geographical location on cross-infection. We will address these limitations in future studies.

Conclusions

This study compared the gut bacterial communities between Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. The results showed that intestinal bacterial community composition differed significantly between the two hosts. In addition, potential pathogens were found in guts of both Hooded Crane and Domestic Goose, suggesting that there might be the risk of disease transmission between wild birds and poultry.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA, PRJEB35710).

References

Alm EW, Daniels-Witt QR, Learman DR, Ryu H, Jordan DW, Gehring TM, et al. Potential for gulls to transport bacteria from human waste sites to beaches. Sci Total Environ. 2018;615:123–30.

Bortoluzzi C, Lumpkins B, Mathis GF, Franca M, King WD, Graugnard DE, et al. Zinc source modulates intestinal inflammation and intestinal integrity of broiler chickens challenged with coccidia and Clostridium perfringens. Poult Sci. 2019;98:2211–9.

Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:382–98.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–6.

Caron A, De Garine-Wichatitsky M, Gaidet N, Chiweshe N, Cumming GS. Estimating dynamic risk factors for pathogen transmission using community-level bird census data at the wildlife/domestic interface. Ecol Soc. 2010;15:299–305.

Chen SX, Wang Y, Chen FY, Yang HC, Gan MH, Zheng SJ. A highly pathogenic strain of Staphylococcus sciuri caused fatal exudative epidermitis in piglets. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:1–6.

Chen JY, Zhou LZ, Zhou B, Xu RX, Zhu WZ, Xu WB. Seasonal dynamics of wintering waterbirds in two shallow lakes along Yangtze River in Anhui Province. Zool Res. 2011;32:540–8.

Chevalier C, Stojanovic O, Colin DJ, Suarez-Zamorano N, Tarallo V, Veyrat-Durebex C, et al. Gut microbiota orchestrates energy homeostasis during cold. Cell. 2015;163:1360–74.

Craven SE, Stern NJ, Line E, Bailey JS, Cox NA, Fedorka-Cray P. Determination of the incidence of Salmonella spp., Campylobacter jejuni, and Clostridium perfringens in wild birds near broiler chicken houses by sampling intestinal droppings. Avian Dis. 2000;44:715–20.

Curtis SK, Kothary MH, Blodgett RJ, Raybourne RB, Ziobro GC, Tall BD. Rugosity in Grimontia hollisae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1215–24.

Delaunay E, Abat C, Rolain JM. Enterococcus cecorum human infection. France. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;7:50–1.

Deng P, Swanson KS. Gut microbiota of humans, dogs and cats: current knowledge and future opportunities and challenges. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:S6–17.

Desai SS, Harrison RA, Murphy MD. Capnocytophaga ochracea causing severe sepsis and purpura fulminans in an immunocompetent patient. J Infect. 2007;54:e107–109.

Dewar ML, Arnould JPY, Dann P, Trathan P, Groscolas R, Smith S. Interspecific variations in the gastrointestinal microbiota in penguins. MicrobiologyOpen. 2013;2:195–204.

Dufrêne M, Legendre P. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr. 1997;67:345–66.

Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–1.

Ekong PS, Fountain-Jones NM, Alkhamis MA. Spatiotemporal evolutionary epidemiology of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza in West Africa and Nigeria, 2006‒2015. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:e70–82.

Erbasan F. Brain abscess caused by Micrococcus luteus in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:2323–8.

Fan PX, Bian BL, Teng L, Nelson CD, Driver J, Elzo MA, et al. Host genetic effects upon the early gut microbiota in a bovine model with graduated spectrum of genetic variation. ISME J. 2020;14:302–17.

Fang J, Wang ZH, Zhao SQ, Li YK, Tang ZY, Yu D, et al. Biodiversity changes in the lakes of the Central Yangtze. Front Ecol Environ. 2006;4:369–77.

Ferraz V, McCarthy K, Smith D, Koornhof HJ. Rothia dentocariosa endocarditis and aortic root abscess. J Infect. 1998;37:292–5.

Flint HJ, Bayer EA, Rincon MT, Lamed R, White BA. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:121–31.

Fox AD, Cao L, Zhang Y, Barter M, Zhao MJ, Meng FJ, et al. Declines in the tuber feeding waterbird guild at Shengjin Lake national nature reserve, China—a barometer of submerged macrophyte collapse. Aquat Conserv-Mar Freshw Ecosyst. 2011;21:82–91.

Galen SC, Witt CC. Diverse avian malaria and other haemosporidian parasites in Andean house wrens: evidence for regional co-diversification by host switching. J Avian Biol. 2014;45:374–86.

Grond K, Ryu H, Baker AJ, Domingo JWS, Buehler DM. Gastro-intestinal microbiota of two migratory shorebird species during spring migration staging in Delaware Bay, USA. J Ornithol. 2014;155:969–77.

Grond K, Lanctot RB, Jumpponen A, Sandercock BK. Recruitment and establishment of the gut microbiome in arctic shorebirds. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2017;93:142.

Grond K, Sandercock BK, Jumpponen A, Zeglin LH. The avian gut microbiota: community, physiology and function in wild birds. J Avian Biol. 2018;49:e01788.

He SD, Zhang ZY, Sun HJ, Zhu YC, Cao XD, Ye YK, et al. Potential effects of rapeseed peptide Maillard reaction products on aging-related disorder attenuation and gut microbiota modulation in d-galactose induced aging mice. Food Funct. 2019;10:4291–303.

Hird SM, Carstens BC, Cardiff S, Dittmann DL, Brumfield RT. Sampling locality is more detectable than taxonomy or ecology in the gut microbiota of the brood parasitic Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater). PeerJ. 2014;2:e321.

Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Yang PC, Wang SK, Chang SC, Ho SW, et al. Bacteremia caused by Arcobacter cryaerophilus 1B. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:489–91.

Jiao SW, Guo YM, Huettmann F, Lei GC. Nest-site selection analysis of hooded crane (Grus monacha) in northeastern china based on a multivariate ensemble model. Zool Sci. 2014;31:430–7.

Jourdain E, Gauthier-Clerc M, Bicout DJ, Sabatier P. Bird migration routes and risk for pathogen dispersion into western mediterranean wetlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:365–72.

Jung A, Chen LR, Suyemoto MM, Barnes HJ, Borst LB. A review of Enterococcus cecorum infection in poultry. Avian Dis. 2018;62:261–71.

Kira J, Isobe N. Helicobacter pylori infection and demyelinating disease of the central Nervous System. J Neuroimmunol. 2019;329:14–9.

Koziel N, Kukier E, Kwiatek K, Goldsztejn M. Clostridium perfringens-epidemiological importance and diagnostics. Med Weter. 2019;75:265–70.

LaFrentz BR, Garcia JC, Waldbieser GC, Evenhuis JP, Loch TP, Liles MR, et al. Identification of four distinct phylogenetic groups in Flavobacterium columnare with fish host associations. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:452–65.

Lalitha P, Srinivasan M, Prajna V. Rhodococcus ruber as a cause of keratitis. Cornea. 2006;25:238–9.

Lan PTN, Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Phylogenetic analysis of cecal microbiota in chicken by the use of 16S rDNA clone libraries. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:371–82.

Lee SH, Kim KK, Rhyu IC, Koh S, Lee DS, Choi BK. Phenol/water extract of Treponema socranskii subsp. socranskii as an antagonist of Toll-like receptor 4 signalling. Microbiology. 2006;152:535–46.

Li G, Du XS, Zhou DF, Li CG, Huang LB, Zheng QK, et al. Emergence of pathogenic and multiple-antibiotic-resistant Macrococcus caseolyticus in commercial broiler chickens. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:1605–14.

Loy A, Pfann C, Steinberger M, Hanson B, Herp S, Brugiroux S, et al. Lifestyle and horizontal gene transfer-mediated evolution of Mucispirillum schaedleri, a core member of the murine gut microbiota. Msystems. 2017;2:e00171.

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020. Version 2019-3. https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Morgavi DP, Rathahao-Paris E, Popova M, Boccard J, Nielsen KF, Boudra H. Rumen microbial communities influence metabolic phenotypes in lambs. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1060.

Muegge BD, Kuczynski J, Knights D, Clemente JC, Gonzalez A, Fontana L, et al. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science. 2011;332:970–4.

Murakami Y, Hanazawa S, Tanaka S, Iwahashi H, Yamamoto Y, Fujisawa S. A possible mechanism of maxillofacial abscess formation: involvement of Porphyromonas endodontalis lipopolysaccharide via the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2001;16:321–5.

Nejrup RG, Licht TR, Hellgren LI. Fatty acid composition and phospholipid types used in infant formulas modifies the establishment of human gut bacteria in germ-free mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3975.

Nielsen HL. First report of Actinomyces europaeus bacteraemia result from a breast abscess in a 53-year-old man. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;7:21–2.

Nocera FP, Papulino C, Del Prete C, Palumbo V, Pasolini MP, De Martino L. Endometritis associated with Enterococcus casseliflavus in a mare: a case report. Asian Pac Trop Biomed. 2017;7:760–2.

Oksanen J, Blanchet G, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, et al. Vegan: community ecology package. Version 2.0–2. 2010.

Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Costa-Hurtado M, Shepherd E, DeJesus E, Smith D, Spackman E, et al. Pathogenicity and transmission of H5 and H7 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in mallards. J Virol. 2016;90:9967–82.

Pate M, Zolnir-Dovc M, Kusar D, Krt B, Spicic S, Cvetnic Z, et al. The first report of Mycobacterium celatum isolation from domestic pig (Sus scrofa domestica) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and an overview of human infections in Slovenia. Vet Med Int. 2011;2011:432954.

Peng WJ, Dong B, Zhang SS, Huang H, Ye XK, Chen LN, et al. Research on rare cranes population response to land use change of nature wetland. J Indian Soc Remote Sens. 2018;46:1795–803.

Perofsky AC, Lewis RJ, Meyers LA. Terrestriality and bacterial transfer: a comparative study of gut microbiomes in sympatric Malagasy mammals. ISME J. 2019;13:50–63.

Ramey AM, Pearce JM, Flint PL, Ip HS, Derksen DV, Franson JC, et al. Intercontinental reassortment and genomic variation of low pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated from northern pintails (Anas acuta) in Alaska: examining the evidence through space and time. Virology. 2010;401:179–89.

Reed C, Bruden D, Byrd KK, Veguilla V, Bruce M, Hurlburt D, et al. Characterizing wild bird contact and seropositivity to highly pathogenic avian influenza a (H5N1) virus in Alaskan residents. Influenza Other Resp. 2014;8:516–23.

Ruiu L. Brevibacillus laterosporus, a pathogen of invertebrates and a broad-spectrum antimicrobial species. Insects. 2013;4:476–92.

Sanders JG, Beichman AC, Roman J, Scott JJ, Emerson D, McCarthy JJ, et al. Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8285.

Scheid PL, Lam TT, Sinsch U, Balczun C. Vermamoeba vermiformis as etiological agent of a painful ulcer close to the eye. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:1999–2004.

Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. eLife. 2013;2:e01202.

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:60.

Smith PA, Pizarro P, Ojeda P, Contreras J, Oyanedel S, Larenas J. Routes of entry of Piscirickettsia salmonis in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Dis Aquat Organ. 1999;37:165–72.

Stanley D, Denman SE, Hughes RJ, Geier MS, Crowley TM, Chen HL, et al. Intestinal microbiota associated with differential feed conversion efficiency in chickens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;96:1361–9.

Stanley D, Hughes RJ, Moore RJ. Microbiota of the chicken gastrointestinal tract: influence on health, productivity and disease. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:4301–10.

Speirs LBM, Rice DTF, Petrovski S, Seviour RJ. The phylogeny, biodiversity, and ecology of the chloroflexi in activated sludge. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2015.

Spence C, Wells WG, Smith CJ. Characterization of the primary starch utilization operon in the obligate anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis: regulation by carbon source and oxygen. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4663–72.

Vendrell D, Balcazar JL, Ruiz-Zarzuela I, de Blas I, Girones O, Muzquiz JL. Lactococcus garvieae in fish: a review. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;29:177–98.

Venugopal AA, Szpunar S, Johnson LB. Risk and prognostic factors among patients with bacteremia due to Eggerthella lenta. Anaerobe. 2012;18:475–8.

Waite DW, Eason DK, Taylor MW. Influence of hand rearing and bird age on the fecal microbiota of the critically endangered kakapo. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4650–8.

Wilkinson TJ, Cowan AA, Vallin HE, Onime LA, Oyama LB, Cameron SJ, et al. Characterization of the microbiome along the gastrointestinal tract of growing turkeys. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–11.

Wise MG, Siragusa GR. Quantitative analysis of the intestinal bacterial community in one- to three-week-old commercially reared broiler chickens fed conventional or antibiotic-free vegetable-based diets. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:1138–49.

Xiang XJ, Zhang FL, Fu R, Yan SF, Zhou LZ. Significant differences in bacterial and potentially pathogenic communities between sympatric hooded crane and greater white-fronted goose. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:163.

Xiong JB, Wang K, Wu JF, Qiuqian LL, Yang KJ, Qian YX, et al. Changes in intestinal bacterial communities are closely associated with shrimp disease severity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:6911–9.

Yang L, Zhou LZ, Song YW. The effects of food abundance and disturbance on foraging flock patterns of the wintering hooded crane (Grus monacha). Avian Res. 2015;6:15.

Yang MJ, Song H, Sun LN, Yu ZL, Hu Z, Wang XL, et al. Effect of temperature on the microflora community composition in the digestive tract of the veined rapa whelk (Rapana venosa) revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Comp Biochem Phys D. 2019;29:145–53.

Zhao LL, Wang G, Siegel P, He C, Wang HZ, Zhao WJ, et al. Quantitative genetic background of the host influences gut microbiomes in chickens. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1163.

Zhu WF, Wei HJ, Chen L, Qiu RL, Fan ZY, Hu B, et al. Characterization of host plasminogen exploitation of Pasteurella multocida. Microb Pathog. 2019;129:74–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank staff of Shenjin Lake National Nature Reserve for providing sample assistance in this study. We also thank Wei Chen, Weiqing Wang, Bingguo Dai, Jian Zhou, Xingran Wang, Zhengrong Zhu for helping us to collect samples.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31772485 and 31801989).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF and LZ conceived and designed the experiments, RF, YD and LC completed the field sampling, RF performed the experiments and drafted the earlier version of the paper, RF, YD, LC and XX contributed in data analysis and paper review. LZ contributed reagents/materials, and reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study complies with the current laws of China. Non-invasive sample collection does not involve the hunting of experimental animals. Obtained the approval of Shengjin Lake National Nature reserve in Anhui Province.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Fig. S1.

A schematic of study area. Fig. S2. Intestinal bacterial alpha-diversity in Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. Fig. S3. Identified phylotype biomarkers ranked by effect size in Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese. Fig. S4. The overlapping of intestinal pathogenic bacterial OTU in Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese.

Additional file 2.

Supporting Information.

Additional file 3.

The identified potential pathogens carried by Hooded Cranes and Domestic Geese in this study. Table S2. The distribution of data analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Table S3. The intestinal bacterial and potentially pathogenic sequences across the samples. Table S4. Indicator species of the treatments, OTUs with a relative abundance of less than 0.05% are not listed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, R., Xiang, X., Dong, Y. et al. Comparing the intestinal bacterial communies of sympatric wintering Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) and Domestic Goose (Anser anser domesticus). Avian Res 11, 13 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00195-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00195-9