Abstract

Background

Seasonal adjustments in body mass and energy budget are important for the survival of small birds in temperate zones. Seasonal changes in body mass, body temperature, gross energy intake (GEI), digestible energy intake (DEI), body fat content, as well as length and mass of the digestive tract, were measured in Chinese Bulbuls (Pycnonotus sinensis) caught in the wild at Wenzhou, China.

Methods

Body mass was determined with a Sartorius balance. The caloric contents of the dried food and feces were then determined using a oxygen bomb calorimeter. Total fat was extracted from the dried carcasses by ether extraction in a Soxhlet apparatus. The digestive tract of each bird was measured and weighed, and was then dried to a constant mass.

Results

Body mass showed a significant seasonal variation and was higher in spring and winter than in summer and autumn. Body fat was higher in winter than in other seasons. GEI and DEI were significantly higher in winter. The length and mass of the digestive tract were greatest in winter and the magnitude of both these parameters was positively correlated with body mass, GEI and DEI. Small passerines typically have higher daily energy expenditure in winter, necessitating increased food consumption.

Conclusions

This general observation is consistent with the observed winter increase in gut volume and body mass in Chinese Bulbuls. These results suggest that Chinese Bulbuls adjust to winter conditions by increasing their body mass, body fat, GEI, DEI and digestive tract size.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Small birds usually show seasonal changes in morphology, physiology and behavior in response to altered environmental conditions (Swanson, [1991]; Zheng et al., [2008a], [2008b]; Nzama et al., [2010]; Liknes and Swanson, [2011]). Seasonal changes in the energy requirements of birds, as well as in food availability and quality, affect their ability to obtain and digest food (Karasov, [1990]). From the point of view of energy requirements, winter is a stressful period for small birds in temperate zones, because thermoregulatory costs increase while food quality and availability decrease (Yuni and Rose, [2005]). The risk of energy requirements exceeding the seasonally available food supply is a strong selective pressure for the evolution of morphological, physiological and behavioral adaptations that enhance the probability of survival over winter (Novoa et al., [1996]; McWilliams and Karasov, [2001]; Starck and Rahmaan, [2003]; Hegemann et al., [2012]). For birds maintaining constant body mass and body composition, time–averaged energy intake equals time–averaged energy use (Hammond and Diamond, [1997]). This balance depends on the interplay between the intake and digestive processing of matter and energy and their allocation among diverse functions, including thermoregulation, growth and reproduction (Afik and Karasov, [1995]; Starck and Rahmaan, [2003]; Caviedes–Vidal et al., [2007]). Increased food intake, hypertrophy of the gastrointestinal tract and the consequent increased absorption of nutrients may be viewed as responses by wintering birds to physical and biotic seasonal habitats (Novoa et al., [1996], McWilliams and Karasov, [2001]).

Phenotypic flexibility is the induced modification of a morphological or physiological trait in response to changes in environmental conditions (Piersma and Drent, [2003]; Starck and Rahmaan, [2003]; Tieleman et al., [2003]); examples are rapid, reversible and repeatable changes in body composition, organ size and digestive processes (Starck, [1999a]; McWilliams and Karasov, [2001]; Starck and Rahmaan, [2003]). Birds resident in temperate climates provide a natural experiment in phenotypic flexibility with respect to body composition, organ size and digestive tract morphology (Pendergast and Boag, [1973]; Paulus, [1982]; Dawson et al., [1983]; Liu and Li, [2006]; Liknes and Swanson, [2011]). Previous research suggests that the avian digestive tract is a suitable organ to study the basic mechanism of phenotypic structural variation (Starck, [1999b]; Guglielmo and Williams, [2003]; Karasov et al., [2004]; Lavin et al., [2008]). Among others, we suggest the following causes: (1) The morphologies of avian digestive tracts are correlated with food composition; frugivorous and nectar–feeding birds have smaller and shorter digestive tracts than granivorous and insectivorous species (Kehoe and Ankney, [1985]; Levey and Karasov, [1989]; Barton and Houston, [1994]; DeGolier et al., [1999]). (2) Many avian species change their diet throughout the year. Birds often switch from high fat foods and carbohydrates in autumn and winter (e.g. seeds and berries) to high protein foods (e.g. insects and new plant tissue) in spring and summer (Bairlein, [1985]; Biebach, [1996]; Novoa et al., [1996]). (3) The avian digestive tract depends not only on resorption and assimilation processes but also on adjustment of its morphology, such as its epithelial resorptive surface dimensions, volume and transport efficiency (Karasov, [1996]; Starck, [1996]; Karasov et al., [2004]). In winter, as the energy demand increases, some species of birds are able to increase digestive efficiency by changes in their digestive tract morphology (Paulus, [1982]; Pulliainen and Tunkkari, [1983]; Novoa et al., [1996]). Indeed, the mass of the digestive tract provides a useful indication of daily energy expenditure. The digestive tract and liver of vertebrates may account for 20–25% of the respiration of an entire animal (Li et al., [2001]; Villarin et al., [2003]). Within species, increases in size of the alimentary organs are associated with increases in basal metabolism (Swanson, [2010]; Karasov et al., [2011]).

The Chinese Bulbul (Pycnonotus sinensis) is a small passerine that is a resident breeder in vast areas of East and South Asia, including central, southern and eastern China. It is the most common bird in Zhejiang Province and has recently spread to central China (MacKinnon and Phillipps, [2000]). Chinese Bulbuls preferentially live in scrub lands, bamboo and coniferous forests, but also inhabit vegetation around villages on deforested plains and hills (Zheng and Zhang, [2002]). They are reported to have a high body temperature (T b), an upper critical temperature (T uc), low BMR, a relatively wide thermal neutral zone (TNZ) (Zhang et al., [2006]) and are able to increase their body mass and BMR in response to colder temperatures (Zheng et al., [2008a]). This species appears to meet increased energy requirements in winter by increasing the mass of certain internal organs and respiratory enzyme activity (Zhang et al., [2008]; Zheng et al., [2010]). Chinese bulbuls are omnivorous, feeding mainly on arthropods (insects and spiders) and mollusks (snails and slugs) in spring and summer and plant foods (buds, fruits and seeds) in autumn and winter (Pang, [1981]; Peng et al., [2008]). We selected this species because: 1) Chinese Bulbuls are common residents in Zhejiang Province and a good species in which to study seasonal change and 2) our previous research on this species (Zheng et al., [2008a]; Peng et al., [2010]; Zheng et al., [2010]; Zhou et al., [2010]; Ni et al., [2011]; Wu et al., [2014]; Zheng et al., [2013]; [2014]) provides critical background information. However, seasonal patterns of energy budgets in wild bulbuls throughout an entire annual cycle have not been previously measured.

We measured the body mass, energy budget and digestive tract morphology of Chinese Bulbuls in all four seasons in Wenzhou, China. We hypothesized that phenotypic variation in overall body mass and digestive organ mass may play important roles in the adaptation of this species to changing seasonal environments. We predicted that Chinese Bulbuls increase their body mass, energy intake, length and mass of their digestive tract in colder seasons.

2 Methods

2.1 Study site and animals

This study was carried out in Wenzhou City, Zhejiang Province (27°29′N, 120°51′E, 14 m in elevation). The climate in Wenzhou is warm–temperate with an average annual rainfall of 1700 mm spread across the entire year with slightly more precipitation during winter and spring. Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 39°C in July to 8°C in January and mean daily minima from 28°C in July to 3°C in January. The mean annual temperature is 18°C. There are seven months (March through September) in which the extreme maximum ambient temperature is above 37°C. Daylight ranges from 14.3 in July to 10.2 h in January. In Wenzhou, the mean temperatures of spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November) and winter (December to February) are 15, 32, 27 and 8°C (data from Wenzhou Bureau of Meteorology).

Chinese Bulbuls were captured in mist nets during the four seasons from 2009 to 2011. Eighteen to 24 adult bulbuls were caught in each season, 88 birds in total. Body mass to the nearest 0.1 g was determined immediately upon capture with a Sartorius balance (model BT25S). Bulbuls were transported to outdoor aviaries and caged for 1 or 2 days (50 cm × 30 cm × 20 cm) under natural photoperiod and temperature before measurement of their energy budget. Food and water were supplied ad libitum. Body temperatures were measured between 21:00 and 23:00 hours by inserting the probe of a digital thermometer (Beijing Normal University Instruments Co.) 3 cm into the cloaca of each bird and taking a reading in 30 s. Animal handling and experimental protocols were approved by the Wenzhou Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the guidelines of the Ornithological Council.

2.2 Energy budget

The energy intake of the birds caught in each season was measured over three days according to previously established methods (Klaassen et al., [2004]; Ni et al., [2011]). Non-absorped food and feces were collected after the 3-day period, separated manually and oven-dried at 70°C for at least 72 h. The caloric contents of the dried food and feces were then determined using a C 200 oxygen bomb calorimeter (IKA Instrument, Germany). Gross energy intake (GEI), fecal energy (FE), digestible energy intake (DEI) and digestibility of energy were calculated according to Li and Wang ([2005]) and Ni et al. ([2011]):

2.3 Body water and fat content

Birds were sacrificed by decapitation at the conclusion of energy budget measurements, the digestive tract was removed and the gizzard, small intestines and rectum were separated (see below). Liver, heart, lung, spleen and kidneys were then removed. The remaining carcasses (including the brain) were weighed to determine wet mass, dried in an oven at 60°C to a constant mass and then weighed (to 1 mg) again to determine dry mass. Total fat was extracted from the dried carcasses by ether extraction in a Soxtec 2050 Soxhlet apparatus (FOSS Instrument, Germany). Body water and fat content were calculated according to Dawson et al. ([1983]) and Zhao et al. ([2010]):

2.4 Measurements of digestive tract morphology

The digestive tract (gizzard, small intestines and rectum) of each bird was measured (±1 mm) and weighed (±0.1 mg). The gizzard, small intestines and rectum were then rinsed with a saline solution to eliminate all gut contents before being dried and reweighed. These organs were then dried to a constant mass over three days at 65°C and weighed to the nearest 0.1 mg (Williams and Tieleman, [2000]; Liu and Li, [2006]).

2.5 Statistics

The data were analyzed using SPSS (version 12.0 for Windows). Distributions of all variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Non-normal distributed data were transformed using natural logarithms. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine the significance of seasonal differences in the measured variables. Least significant difference (LSD) post hoc tests were used when differentiation among seasons was required. Seasonal differences in the measured variables, except for those in body mass and temperature, were also evaluated using an ANCOVA with body mass as a covariate where appropriate. For percentage data, an arcsine-square-root transformation was carried out prior to analysis to normalize the data. The results are expressed as mean ± SE, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Body mass and temperature

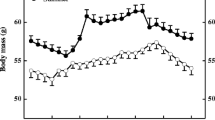

The body mass of Chinese Bulbuls showed a significant seasonal variation (ANOVA, F 3,84 = 8.493, p < 0.001, Table 1); birds caught in winter and spring were significantly heavier than those caught in summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05). Body temperature also showed significant seasonal variation (ANOVA, F 3,84 = 2.957, p < 0.05, Table 1); birds caught in winter had significantly lower body temperatures than those caught in spring, summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05).

3.2 Body fat and water content

Body fat content showed significant seasonal variation (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 11.015, p < 0.001; Table 1) and was markedly higher in autumn and winter than in summer (post hoc, p < 0.05). No significant seasonal variation was found in water content (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 1.447, p > 0.05, Table 1).

3.3 Energy intake and digestibility

Gross energy intake (GEI) varied significantly with season (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 8.886, p < 0.001, Table 1). The GEI of bulbuls caught in winter was 23.2% to 63.9% higher than that of birds caught in spring, summer and autumn. Significant seasonal variation was also apparent in fecal energy (FE) (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 7.955, p < 0.001, Table 1). The FE of bulbuls caught in winter and spring was significantly higher than that of birds caught in summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05). Digestible energy intake (DEI) also showed significant seasonal variation (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 4.090, p < 0.01, Table 1); the DEI of birds caught in winter was 28.4% to 47.2% higher than that of birds caught in spring, summer and autumn. However, no significant seasonal variation was found in digestibility (ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 1.074, p > 0.05, Table 1). Log body mass was positively correlated with the log of GEI and DEI (Figures 1 and 2).

3.4 Digestive tract morphology

The length of the complete digestive tract and small intestines varied significantly with season (ANCOVA, total digestive tract, F 3,83 = 9.464, p < 0.001; small intestines, F 3,83 = 7.555, p < 0.001, Table 2), being longer in birds caught in winter than in birds caught in spring, summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05). The log of digestive tract length is positively correlated with log body mass (r2 = 0.198, p < 0.001, Figure 3a), GEI (r2 = 0.095, p < 0.01, Figure 4a) and DEI (r2 = 0.071, p < 0.05, Figure 5a). No significant seasonal variation was apparent in gizzard or rectum length (ANCOVA, gizzard, F 3,83 = 1.353, p > 0.05; rectum, F 3,83 = 0.984, p > 0.05, Table 2).

Significant seasonal variation was apparent in both the wet and dry mass of the complete digestive tract (ANCOVA, wet mass, F 3,83 = 6.805, p < 0.001; dry mass, F 3,83 = 11.850, p < 0.001, Table 2); birds caught in winter had a heavier digestive tract than those caught in spring, summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05). The log of wet and dry digestive tract mass was positively correlated with log body mass (wet mass, r2 = 0.135, p < 0.001; dry mass, r2 = 0.420, p < 0.001, Figure 3b and c), GEI (wet mass, r2 = 0.094, p < 0.01; dry mass, r2 = 0.153, p < 0.001, Figure 4b and c) and DEI (wet mass, r2 = 0.063, p < 0.05; dry mass, r2 = 0.047, p < 0.05, Figure 5b and c). Wet and dry gizzard mass were significantly (wet mass: ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 10.212, p < 0.001; dry mass: ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 4.523, p < 0.01, Table 2) higher in spring than in summer and autumn (post hoc, p < 0.05). The wet and dry mass of the small intestines also varied significantly with season (wet mass: ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 9.195, p < 0.001; dry mass: ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 16.856, p < 0.001, Table 2). The wet mass of the small intestines of birds caught in winter was 20.5% to 26.0% higher than those of their spring, summer and autumn counterparts, whereas the dry mass was 26.6% to 30.4% higher. The wet and dry mass of the rectum also varied significantly with season (wet mass: ANCOVA, F 3,83 = 2.917, p < 0.05; dry mass: F 3,83 = 16.856, p < 0.01, Table 2). The wet rectal mass was higher in birds caught in autumn than in those caught in spring, summer and winter (post hoc, p < 0.05), but rectal dry mass was lower in birds caught in summer than in those caught in spring, autumn and winter (post hoc, p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

We found significant seasonal variation in body mass, body fat, GEI, FE and DEI in Chinese Bulbuls, all of which were higher in winter than in other seasons. Birds caught in winter also had significantly longer and heavier digestive tracts than those caught in other seasons.

4.1 Effect of season on body mass and body composition

Seasonal changes in body mass, especially in small birds, are considered an adaptive strategy essential for survival (Pendergast and Boag, [1973]; Cooper, [2000]). It has been reported that many small birds, such as Common Redpolls (Acanthis flammea) (Pohl and West, [1973]), American Goldfinches (Carduelis tristis) (Dawson and Carey, [1976]), Darkeyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis) (Swanson, [1991]), Chinese Bulbuls (Zheng et al., [2008a]), Eurasian Tree Sparrows (Passer montanus) (Zheng et al., [2008b]), Red-winged Starlings (Onychognathus morio) (Chamane and Downs, [2009]), Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) and White-breasted Nuthatchs (Sitta carolinensis) (Liknes and Swanson, [2011]) increase their body mass in winter and spring. In this study, as earlier reported, Chinese Bulbuls increase mass in winter and spring.

A variety of physiological responses associated with winter acclimatization in small birds have been identified. These include winter fuel storage, increased basal metabolic rates and seasonal changes in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Marsh and Dawson, [1989]). Increased body fat levels are common in many temperate wintering passerines, enabling these birds to meet thermoregulatory demands and provide a nutritional buffer against temporary foraging restrictions caused by inclement weather (Dawson and Marsh, [1986]; Swanson, [1991]; O’Connor, [1995]). Similar increases in body fat associated with seasonal acclimatization have been observed in House Finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) (Dawson et al., [1983]; O’Connor, [1995]), Lesser Scaups (Aythya affinis) (Austin and Fredrickson, [1987]), Dark-eyed Juncos (Swanson, [1991]), Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa lapponica) ( Landys-Ciannelli et al., [2003] ), Juniper Titmice (Baeolophus ridgwayi) and Mountain Chickadees (Poecile gambeli) (Cooper, [2007]). The energy sparing hypothesis (King, [1961]) states that winter birds would use more of their fat stores overnight than summer birds and lead to a greater need to replenish stores daily than in any other season (especially summer). In support of this hypothesis, we show that winter fattening is characterized by increased body mass in winter acclimatized birds in contrast to summer acclimatized birds.

It is generally recognized that a positive energy balance is a prerequisite for the accumulation of fat. This positive balance results from an adaptively increased energy income that periodically exceeds energy output as birds establish and replenish their fat reserves (Swanson, [1991]; O’Connor, [1995]; Cooper, [2007]). An increase in fat reserves can support increased overnight energy expenditures (lower temperatures and longer nights during winter) and supply emergency energy reserves during periods of resource shortage (snowfalls and ice storms) (Stokkan et al., [1985]; O’Connor, [1995]).

4.2 Effect of seasonal acclimatization on energy intake and digestibility

Body mass has been used as an index of the general condition in animals, the assumption being that peak annual mass is associated with peak condition (Kelly and Weathers, [2002]). Energy intake can compensate for the energy expended in thermogenesis, essential for survival (Evans, [1976]; Reinecke et al., [1982]; Hegemann et al., [2012]). We found that the body mass of Chinese Bulbuls was highest in spring and winter and that this was paralleled by changes in GEI and DEI (Table 1; Figures 1 and 2). Chinese Bulbuls caught in spring and winter showed significantly higher GEI and DEI: both increased with lower ambient temperatures and poor food quality. GEI was 50% and 69% higher in spring and winter than in summer, and DEI was 42% and 91% higher in spring and winter than in summer.

Many studies have found evidence of significant seasonal effects on daily energy intake within species (Bryant et al., [1985]; Kelly, [1998]; Weathers and Sullivan, [1993]; Webster and Weathers, [2000]; Guillemette and Butler, [2012]; Hegemann et al., [2012]). For example, Kendeigh ([1945]) found that the GEI of English House Sparrows (P. domesticus) was 51% higher in winter than in summer. Similarly, Stokkan et al. ([1986]) found that Rock Ptarmigans (Lagotus muta) consume twice as much food between February and March as they do in August, while Lou et al. ([2013]) found that the GEI and DEI of Elliot’s Pheasants (Syrmaticus ellioti) were respectively 51% and 53% higher in winter than in summer. Similar changes in food intake associated with seasonal acclimatization and migration have been observed in other birds, including Kingfishers (Ceryle alcyon) (Kelly, [1998]), Red Knots (Calidris canutus) and Common Sandpipers (Actitis hypoleucos) (Kvist and Lindström, [2003]), as well as in small mammals such as Wood Mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) (Corp et al., [1999]) and Mongolian Gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) (Li and Wang, [2005]). This suggests that enhancement of GEI and DEI is a response to higher energy demands for small endotherms in general (Stokkan et al., [1986]; Li and Wang, [2005]).

4.3 Effect of seasonal acclimatization on digestive tract morphology

Seasonal changes in digestive tract morphology have been demonstrated in many birds (Pendergast and Boag, [1973]; Reinecke et al., [1982]; Pulliainen and Tunkkari, [1983]; Novoa et al., [1996]). Environmental conditions that cause increased nutritional or energy requirements could be responsible for these observed increases in the size of digestive organs. The digestive modulation model predicts an increase in the size of the intestines (length, circumference and surface area) in response to either increasing or decreasing food quality (Sibley, [1981]; McWilliams and Karasov, [2001]).

A question arises about the ecological implications of having a larger gut in winter and autumn. Birds typically consume more food in winter and autumn, which appears to stimulate the enlargement of digestive organs such as the gizzard, small intestines, rectum and the overall digestive tract. Increasing gut size in this way in response to decreasing food quality can yield several benefits. One is that it allows an increase in the mean retention time of the digesta, thereby increasing their digestibility if the ingestion rate is constant, or it allows a constant mean retention time, thereby maintaining digestive efficiency if ingestion increases (McWilliams and Karasov, [2001]; Karasov, [2011]; Karasov et al., [2011]). For example, Sibley ([1981]) found that the small intestines of European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) were longer in winter when they fed predominantly on seeds and berries than in other seasons. Starck ([1999b]) also found that there was a significant relationship between food digestibility and small intestine length in Willow Ptarmigans (L. lagopus), Spruce Grouse (Falcipennis canadensis), Spur-winged Geese (Plectropterus gambensis) and Gadwalls (A. strepera). Our results show that Chinese Bulbuls display marked seasonal changes in the length and mass of their digestive tract. The length of both the complete digestive tract and small intestines were significantly longer in winter than in spring, summer and autumn. The wet and dry mass of both the complete digestive tract and the small intestines were also significantly greater in winter than in other seasons. Seasonal trends in the length and mass of digestive tracts were closely correlated with those in body mass, GEI and DEI (Figures 3, 4, 5). These seasonal differences in the weight of the digestive tract were probably caused by reduced winter food quality and quantity. In winter, bulbuls in Wenzhou mainly feed on plants despite the much colder mean temperature of 8°C (Pang, [1981]; Peng et al., [2008]). In bulbuls, as in other small birds, increases in digestive tract capacity, as well as elevated uptake of nutrients by the small intestines, appear to increase the rate of assimilation of nutrients, thereby increasing body mass and improving winter survival (Karasov et al., [2011]).

During the winter, birds have a relatively high daily energy expenditure, requiring enlarged abdominal organs for support (McKinney and McWilliams, [2005]; Karasov et al., [2011]). Birds consume more food in winter, which apparently stimulates the enlargement of organs such as the liver, intestines and the stomach (Williams and Tieleman, [2000]).

5 Conclusions

In summary, our key findings were: 1) Chinese Bulbuls have higher body mass and body fat in winter. This is consistent with our prediction that marked winter increases in GEI and DEI are aspects of winter acclimatization and that seasonal variation in digestive performance in bulbuls is similar to that observed in other small, temperate bird species. 2) The length and wet and dry mass of the digestive tract of Chinese Bulbuls are higher in winter and have a significantly positive relationship with body masses, GEI and DEI.

References

Afik D, Karasov WH: The trade-offs between digestion rate and efficiency in warblers and their ecological implications. Ecology 1995, 76: 2247–2257. 10.2307/1941699

Austin JE, Fredrickson LH: Body and organ mass and body composition of postbreeding female lesser scaup. Auk 1987, 104: 694–699.

Bairlein F: Efficiency of food utilization during fat deposition in the long-distance migratory garden warbler, Sylvia borin . Oecologia 1985, 68: 118–125. 10.1007/BF00379483

Barton NWH, Houston DC: Morphological adaptation of the digestive tract in relation to feeding ecology of raptors. J Zool 1994, 232: 133–150. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb01564.x

Biebach H: Energetics of Winter and Migratory Fattening. In Avian Energetics and Nutritional Ecology. Edited by: Carey C. Chapman and Hall, New York; 1996:280–323. 10.1007/978-1-4613-0425-8_9

Bryant DM, Hails CJ, Prys–Jones R: Energy expenditure by freeliving dippers ( Cinclus cinclus ) in winter. Condor 1985, 87: 177–186. 10.2307/1366880

Caviedes-Vidal E, McWhorter TJ, Lavin SR, Chediack JG, Tracy CR, Karasov WH: The digestive adaptation of flying vertebrates: high intestinal paracellular absorption compensates for smaller guts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007, 104: 19132–19137. 10.1073/pnas.0703159104

Chamane S, Downs CT: Seasonal effects on metabolism and thermoregulation abilities of the red-winged starling ( onychognathusmorio ). J Therm Biol 2009, 34: 337–341. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2009.06.005

Cooper SJ: Seasonal energetics of mountain chickadees and juniper titmice. Condor 2000, 102: 635–644. 10.1650/0010-5422(2000)102[0635:SEOMCA]2.0.CO;2

Cooper SJ: Daily and seasonal variation in body mass and visible fat in mountain chickadees and juniper titmice. Wilson J Ornithol 2007, 119: 720–724. 10.1676/06-183.1

Corp N, Gorman ML, Speakman JR: Daily energy expenditure of free- living male wood mice in different habitats and seasons. Funct Ecol 1999, 13: 1365–2435. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00353.x

Dawson WR, Carey C: Seasonal acclimation to temperature in cardueline finches. J Comp Physiol 1976, 112: 317–333. 10.1007/BF00692302

Dawson WR, Marsh RL: Winter fattening in the American goldfinch and the possible role of temperature in its regulation. Physiol Zool 1986, 59: 353–369.

Dawson WR, Marsh RL, Buttemer WA, Carey C: Seasonal and geographic variation of cold resistance in house finches Carpodacus mexicanus . Physiol Zool 1983, 56: 353–369.

DeGolier TF, Mahoney SA, Duke GE: Relationship of cecal lengths to food habits, taxonomic position, and intestinal lengths. Condor 1999, 101: 622–634. 10.2307/1370192

Evans PR: Energy balance and optimal foraging strategies in shorebirds: some implications for their distributions and movements in the non–breeding season. Ardea 1976, 64: 117–139.

Guglielmo CG, Williams TD: Phenotypic flexibility of body composition in relation to migratory state, age, and sex in the western sandpiper ( Calidris mauri ). Physiol Biochem Zool 2003, 76: 84–98. 10.1086/367942

Guillemette M, Butler PJ: Seasonal variation in energy expenditure is not related to activity level or water temperature in a large diving bird. J Exp Biol 2012, 215: 3161–3168. 10.1242/jeb.061119

Hammond KA, Diamond J: Maximum sustained energy budgets in humans and animals. Nature 1997, 386: 457–462. 10.1038/386457a0

Hegemann A, Matson KD, Versteegh MA, Tieleman BI: Wild skylarks seasonally modulate energy budgets but maintain energetically costly inflammatory immune responses throughout the annual cycle. PLoS One 2012, 7: e36358. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036358

Karasov WH: Digestion in birds: chemical and physiological determinants and ecological implications. Stud Avian Biol 1990, 13: 39l-415l.

Karasov WH: Digestive Plasticity in Avian Energetics and Feeding Ecology. In Avian Energetics and Nutritional Ecology. Edited by: Carey C. Chapman and Hall, New York; 1996:61–84. 10.1007/978-1-4613-0425-8_3

Karasov WH: Digestive physiology: a view from molecules to ecosystem. Am J Physiol 2011, 301: R276-R284.

Karasov WH, Pinshow B, Starck JM, Afik D: Anatomical and histological changes in the alimentary tract of migrating blackcaps ( Sylvia atricapilla ): a comparison among fed, fasted, food–restricted, and refed birds. Physiol Biochem Zool 2004, 77: 149–160. 10.1086/381465

Karasov WH, Martínez Del Rio C, Caviedes-Vidal E: Ecological physiology of diet and digestive systems. Annu Rev Physiol 2011, 73: 69–93. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142152

Kehoe FP, Ankney CD: Variation in digestive organ size among five species of diving drcks ( Aythya spp.). Can J Zool 1985, 63: 2339–2342. 10.1139/z85-346

Kelly JP: Behavior and energy budgets of belted kingfishers in winter. J Field Ornitho 1998, 69: 75–84.

Kelly JP, Weathers WW: Effects of feeding time constraints on body mass regulation and energy expenditure in wintering dunlin ( Calidris alpina ). Behav Ecol 2002, 13: 766–775. 10.1093/beheco/13.6.766

Kendeigh SC: Effect of temperature and season on energy resources of the English sparrow. Auk 1945, 66: 766–775.

King JR: The bioenergetics of vernal premigratory fat deposition in the white-crowned sparrow. Condor 1961, 63: 128–142. 10.2307/1365526

Klaassen M, Oltrogge M, Trost L: Basal metabolic rate, food intake, and body mass in cold- and warm-acclimated Garden Warblers. Comp Biochem Physiol A 2004, 137: 639–647. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2003.12.004

Kvist A, Lindström Å: Gluttony in migratory waders – unprecedented energy assimilation rates in vertebrates. Oikos 2003, 103: 397–402. 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12259.x

Landys-Ciannelli MM, Piersma T, Jukema J: Strategic size changes of internal organs and muscle tissue in the bar-tailed godwit during fat storage on a spring stopover site. Funct Ecol 2003, 17: 151–159. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00715.x

Lavin SR, Karasov WH, Ives AR, Middleton KM, Garland T Jr: Morphometrics of the avian small intestine compared with that of nonflying mammals: a phylogenetic approach. Physiol Biochem Zool 2008, 81: 526–550. 10.1086/590395

Levey DJ, Karasov WH: Digestive responses of temperate birds switched to fruit or insect diets. Auk 1989, 106: 675–686. 10.2307/4087757

Li XS, Wang DH: Seasonal adjustments in body mass and thermogenesis in Mongolian gerbils ( Meriones unguiculatus ): the roles of short photoperiod and cold. J Comp Physiol B 2005, 175: 593–600. 10.1007/s00360-005-0022-2

Li QF, Sun RY, Huang CX, Wang ZK, Liu XT, Hou JJ, Liu JS, Cai LQ, Li N, Zhang SZ, Wang Y: Cold adaptive thermogenesis in small mammals from different geographical zones of China. Comp Biochem Physiol A 2001, 129: 949–961. 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00357-9

Liknes ET, Swanson DL: Phenotypic flexibility of body composition associated with seasonal acclimatization in passerine birds. J Therm Biol 2011, 36: 363–370. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2011.06.010

Liu JS, Li M: Phenotypic flexibility of metabolic rate and organ masses among tree sparrows Passer montanus in seasonal acclimatization. Acta Zool Sin 2006, 52: 469–477.

Lou Y, Yu TL, Huang CM, Zhao T, Li HH, Li CJ: Seasonal variations in the energy budget of Elliot’s pheasant ( syrmaticus ellioti ) in cage. Zool Res 2013, 34: E19-E25.

MacKinnon J, Phillipps K: A Field Guide to the Birds of China. Oxford University Press, London; 2000.

Marsh RL, Dawson WR: Avian Adjustments to Cold. In Advances in Comparative and Environmental Physiology 4: Animal Adaptation to Cold. Edited by: Wang LCH. Springer, New York; 1989:205–253.

McKinney RA, McWilliams SR: A new model to estimate daily energy expenditure for wintering waterfowl. Wilson Bull 2005, 117: 44–55. 10.1676/04-060

McWilliams SR, Karasov WH: Phenotypic flexibility in digestive system structure and function in migratory birds and its ecological significance. Comp Biochem Physiol A 2001, 128: 579–593. 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00336-6

Ni XY, Lin L, Zhou FF, Wang XH, Liu JS: Effect of photoperiod on body mass, organ masses and energy metabolism in Chinese bulbul ( Pycnonotus sinensis ). Acta Ecol Sin 2011, 31: 1703–1713.

Novoa FF, Veloso C, López–Calleja V, Bozinovic F: Seasonal changes in diet, digestive morphology and digestive efficiency in the rufous–collared sparrow ( Zonotrichia capensis ) in central Chile. Condor 1996, 98: 873–876. 10.2307/1369876

Nzama SN, Downs CT, Brown M: Seasonal variation in the metabolism-temperature relation of house sparrow ( passer domesticus ) in KwaZulu-Natal, south Africa. J Therm Biol 2010, 35: 100–104. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2009.12.002

O’Connor TP: Metabolic characteristics and body composition in house finches: effects of seasonal acclimatization. J Comp Physiol B 1995, 165: 298–305. 10.1007/BF00367313

Pang BZ: Diet habit of Pycnonotus sinensis . Chin J Zool 1981, 4: 75–76.

Paulus SL: Gut morphology of gadwalls in Louisiana in winter. J Wildl Manage 1982, 46: 483–489. 10.2307/3808662

Pendergast BA, Boag DA: Seasonal changes in the internal anatomy of spruce grouse in Alberta. Auk 1973, 90: 307–317.

Peng HY, Wen QH, Huang J, Huang YX: The study of spring diet habit of three species of pycnonotidae. Sichuang J Zool 2008, 27: 99–101.

Peng LJ, Tang XL, Liu JS, Meng HT: The effect of thyroid hormone on basal thermogenesis ( pycnonotus sinensis ). Acta Ecol Sin 2010, 30: 1500–1507.

Piersma T, Drent J: Phenotypic flexibility and the evolution of organismal design. Trends Ecol Evol 2003, 18: 228–233. 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00036-3

Pohl H, West GC: Daily and seasonal variation in metabolic response to cold during rest and exercise in the common redpoll. Comp Biochem Physiol A 1973, 45: 851–867. 10.1016/0300-9629(73)90088-1

Pulliainen E, Tunkkari P: Seasonal changes in the gut length of the willow grouse ( lagopus lagopus ) in Finnish Lapland. Ann Zool Fennici 1983, 20: 53–56.

Reinecke KJ, Stone TL, Owen RB Jr: Seasonal carcass composition and energy balance of female black ducks in Maine. Condor 1982, 84: 420–426. 10.2307/1367447

Sibley RM: Strategies in Digestion and Defecation. In Physiological Ecology: an Evolutionary Approach to Resource Use. Edited by: Townsend CR, Calow P. Blackwell, Oxford; 1981:109–139.

Starck JM: Phenotypic plasticity, cellular dynamics, and epithelial turnover of the intestine of Japanese quail ( Coturnix coturnix japonica ). J Zool 1996, 238: 53–79. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05379.x

Starck JM: Phenotypic flexibility of the avian gizzard: rapid, reversible and repeated changes of organ size in response to changes in dietary fibre content. J Exp Biol 1999, 202: 3171–3179.

Starck JM: Structural flexibility of the gastro–intestinal tract of vertebrates – implications for evolutionary morphology. Zool Anz 1999, 238: 87–101.

Starck JM, Rahmaan GHA: Phenotypic flexibility of structure and function of the digestive system of Japanese quail. J Exp Biol 2003, 206: 1887–1897. 10.1242/jeb.00372

Stokkan KA, Harvey S, Klandorf H, Blix AS: Endocrine changes associated with fat deposition and mobilization in Svalbard ptarmigan ( Lagopus taurus hyperboreas ). Gen Comp Endocrinol 1985, 58: 76–80. 10.1016/0016-6480(85)90137-6

Stokkan KA, Mortensen A, Blix AS: Food intake, feeding rhythm, and body mass regulation in Svalbard rock ptarmigan. Am J Physiol 1986, 251: R264-R267.

Swanson DL: Seasonal adjustments in metabolism and insulation in the dark-eyed junco. Condor 1991, 93: 538–545. 10.2307/1368185

Swanson DL: Seasonal Metabolic Variation in Birds: Functional and Mechanistic Correlates. In Current Ornithology. Edited by: Thompson CF. Springer, Berlin; 2010:75–129.

Tieleman BI, Williams JS, Buschur ME, Brown CR: Phenotypic variation of larks along an aridity gradient: are desert birds more flexible? Ecology 2003, 84: 1800–1815. 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1800:PVOLAA]2.0.CO;2

Villarin JJ, Schaeffer PJ, Markle RA, Lindstedt ST: Chronic cold exposure increases liver oxidative capacity in the marsupial Monodelphis domestica . Comp Biochem Physiol A 2003, 136: 621–630. 10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00210-1

Weathers WW, Sullivan KA: Seasonal patterns of time and energy allocation by birds. Physiol Zool 1993, 66: 511–536.

Webster MD, Weathers WW: Seasonal changes in energy and water use by verdins, Auriparus flaviceps . J Exp Biol 2000, 203: 3333–3344.

Williams J, Tieleman BI: Flexibility in basal metabolic rate and evaporative water loss among hoopoe larks exposed to different environmental temperatures. J Exp Biol 2000, 203: 3153–3159.

Wu YN, Lin L, Xiao YC, Zhou LM, Wu MS, Zhang HY, Liu JS: Effects of temperature acclimation on body mass and energy budget in the Chinese bulbul Pycnonotus sinensis . Zool Res 2014, 35: 33–41.

Yuni LPEK, Rose RW: Metabolism of winter-acclimatized New Holland honeyeaters Phylidonyris novaehollandiae from Hobart, Tasmania. Acta Zool Sin 2005, 51: 338–343.

Zhang YP, Liu JS, Hu XJ, Yang Y, Chen LD: Metabolism and thermoregulation in two species of passerines from south-eastern China in summer. Acta Zool Sin 2006, 52: 641–647.

Zhang GK, Fang YY, Jiang XH, Liu JS, Zhang YP: Adaptive plasticity in metabolic rate and organ masses among Pycnonotus sinensis , in seasonal acclimatization. Chin J Zool 2008, 43: 13–19.

Zhao ZJ, Chi QS, Cao J, Han YD: The energy budget, thermogenic capacity and behavior in Swiss mice exposed to a consecutive decrease in temperatures. J Exp Biol 2010, 213: 3988–3997. 10.1242/jeb.046821

Zheng GM, Zhang CZ: Birds in China. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing; 2002.

Zheng WH, Li M, Liu JS, Shao SL: Seasonal acclimatization of metabolism in Eurasian tree sparrows ( Passer montanus ). Comp Biochem Physiol A 2008, 151: 519–525. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.009

Zheng WH, Liu JS, Jang XH, Fang YY, Zhang GK: Seasonal variation on metabolism and thermoregulation in Chinese bulbul. J Therm Biol 2008, 33: 315–319. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.03.003

Zheng WH, Fang YY, Jang XH, Zhang GK, Liu JS: Comparison of thermogenic character of liver and muscle in Chinese bulbul Pycnonotus sinensis between summer and winter. Zool Res 2010, 31: 319–327.

Zheng WH, Lin L, Liu JS, Pan H, Cao MT, Hu YL: Physiological and biochemical thermoregulatory responses of Chinese bulbuls pycnonotus sinensis to warm temperature: phenotypic flexibility in a small passerine. J Therm Biol 2013, 38: 483–490. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2013.03.003

Zheng WH, Liu JS, Swanson DL: Seasonal phenotypic flexibility of body mass, organ masses, and tissue oxidative capacity and their relationship to RMR in Chinese bulbuls. Physiol Biochem Zool 2014, 87: 432–444. 10.1086/675439

Zhou W, Wang YP, Chen DH, Liu JS: Diurnal rhythms of Chinese bulbul ( Pycnonotus sinensis ) body temperature, body mass, and energy metabolism. Chin J Ecol 2010, 29: 2395–2400.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr David L. Swanson for providing several references. We thank Dr Ron Moorhouse revising the English and providing some suggestions. This study was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31070366 and No. 31470472), the Natural Science Foundation (LY13C030005) in Zhejian Province and the Zhejiang Province ‘Xinmiao’ Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

JL provided the research idea and designed the experiments. MW, YX and FY conducted the experiments and collected the data. MW and LZ finished the data analysis, compiled the results and wrote the first draft of the article. JL and WZ supervised the research and revised the draft. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, M., Xiao, Y., Yang, F. et al. Seasonal variation in body mass and energy budget in Chinese bulbuls (pycnonotus sinensis). Avian Res 5, 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-014-0004-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-014-0004-8