Abstract

Background

Stress is a critical problem facing many healthcare institutions. The consequences of stress include increased provider burnout and decreased quality of care for patients. Ironically, a key factor that may help buffer the impact of stress on provider well-being and patient health outcomes—compassion—is low in healthcare settings and declines under stress. This gives rise to an urgent question: what practical steps can be taken to increase compassion, thereby benefitting both provider well-being and patient care?

Methods

We investigated the relative effectiveness of a short, 10-minute session of loving-kindness meditation (LKM) to increase compassion and positive affect. We compared LKM to a non-compassion positive affect induction (PAI) and a neutral visualization (NEU) condition. Self- and other-focused affect, self-reported measures of social connection, and semi-implicit measures of self-focus were measured pre- and post- meditation using repeated measures ANOVAs and via paired sample t-tests for follow-up comparisons.

Results

Findings show that LKM improves well-being and feelings of connection over and above other positive-affect inductions, at both explicit and implicit levels, while decreasing self-focus in under 10 minutes and in novice meditators.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that LKM may be a viable, practical, and time-effective solution for preventing burnout and promoting resilience in healthcare providers and for improving quality of care in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

A growing body of research indicates that high levels of stress in the healthcare field lead to negative outcomes—for medical providers, healthcare staff, and patients—and that a large part of the damage can be traced to the deleterious effects of stress on compassion and social connection [1]–[6]. Yet the question of how to increase compassion in a way that is practical given the tight schedules of medical professionals has not been answered.

In this paper, we first discuss research on healthcare burnout and its impact on quality of care and compassion. We then discuss what is known about the benefits of compassion, including its potential to increase provider resilience and patient outcomes. Finally, we present a possible solution by considering the affective consequences of a brief compassion intervention that has the advantage of being easily implemented in a short duration of time and by novices.

Background

Stress begins early in medical school and continues to influence providers’ mental health and well-being throughout their medical careers. Nearly half of medical students experience stress-related burnout during medical school training [7],[8], and 11% report suicidal ideation as a result of burnout, decreased quality of life, and depressive symptoms. In medical residents, nearly 20% report below-average mental health – double that of the general population of the same age [9]. Even more experienced professionals, including both nurses and providers, report high levels of emotional- and job- stress [10]. These in turn lead to burnout rates as high as 70%, and an increased level of dissatisfaction with work-life balance compared to the general population [11].

The stress and burnout experienced by healthcare providers not only affects their own health and psychological well-being but also directly impacts the quality of care they provide to patients. Burnout among residents, nurses, and doctors increases the likelihood of sub-standard patient care practices and attitudes, errors in treatment or medication, and hospital-acquired infections [12]–[14]. In addition to objective errors in care, stress and burnout decreases provider compassion, affecting not just medical residents, but also nursing and dental students [15]–[17]. High levels of stress and negative affect lead to an increase in self-focused attention [18],[19], directing attentional resources away from others and decreasing the ability to feel connected to others and express compassion.

Unfortunately, this lack of compassion likely explains the frequency with which patients report negative experiences with the medical system. Sixty-four percent of Americans have experienced unkind behavior in health care settings, including the failure to connect on a personal level (38%), rudeness (36%), and poor listening skills (35%) [20]. Such experiences are not trivial. Eighty-seven percent of Americans would prefer kind treatment by providers regardless of appointment wait times, distance, and costs. Ninety percent would switch to kinder healthcare providers, 72% would be willing to pay more, and 88% would travel longer distances [20]. Patients interviewed about their health care experiences frequently asked ‘where has all the humanity gone?’ [21], and those who were dissatisfied with the care they received often pointed to the lack of compassion given. Patients who decide to enter litigation with their provider often do so because their provider lacked compassion (e.g., perceived unavailability, disregard for patient and family concerns, poor delivery of information, and lack of understanding) [22]. In contrast, patients are less likely to sue a provider for malpractice if they experience a positive relationship with their provider [23].

Compassion is not just linked to patient reports. Providers themselves agree that compassion is essential for patient care. In a recent, nationally representative survey by Dignity Health, the fifth largest healthcare system in the U.S., compassionate care was observed as crucial for predicting quality healthcare [20]. Eighty-five percent of patients and 76% of providers agreed that compassionate care is necessary for successful medical treatment [24]. Unfortunately, only 50% to 60% of patients and providers experience the healthcare system as providing compassionate care and report that positive affect, in general, is low in the healthcare industry [24],[25].

The benefits of compassion for patients and providers

The desire for compassionate care should not be viewed simply as a subjective preference. Research suggests that it is an indispensable part of quality medical care that measurably improves objective health outcomes. For example, in one telling study, watching as little as 40 s of compassionate communication from a provider on videotape was sufficient to reduce anxiety in breast cancer patients [6]. Neuroimaging suggests that this effect goes beyond purely subjective self-report: an fMRI study showed that, compared to standard procedures, patients who were given an empathic, patient-centered interview showed decreased neural activation in the anterior insula, a region associated with pain, when receiving painful electric shocks [26]. In addition to subjective well-being, compassionate care also improves physical outcomes. For example, diabetic patients whose provider scored high (versus moderate or low) on compassion had better metabolic control (versus moderate or low control) and fewer metabolic complications [5]. Provider compassion (as rated by the patient) also predicts shorter duration and severity of the common cold [1] and improved patient satisfaction, treatment compliance, and health outcomes [2] in a broad array of patient populations [3],[4].

Compassion is not only important for the successful treatment of patients but also for reducing burnout and improving health outcomes in providers themselves [27]. Lower feelings of compassion and social connection deteriorate healthcare provider health [28], whereas working in a hospital environment that embraces compassion-based values yields higher employee well-being and maintains affective organizational commitment [29],[30]. Similarly, nurses who reported low social support experienced more stress and anger whereas a more compassionate work environment was associated with more positive affect [31]. Perhaps most importantly, compassion appears to buffer the effects of stress on well-being. A study conducted on over 800 people found that while stress generally predicted greater mortality, this link was absent in those who were engaged in compassionate activities [32], perhaps because it improves resilience and increases adaptive profiles of stress reactivity [33]. As a consequence, individuals who engage in compassionate actions show improved health and longer lifespans [34],[35].

The present study

In sum, research shows that stress and burnout levels in medical organizations are high, medical treatment is suffering as a consequence, and both patients and providers are paying the price. There is a growing need and desire for a more compassionate workplace that includes a greater feeling of social connection [15],[36],[37]. Studies support the positive benefits of meditation and compassion interventions on a number of health and well-being outcomes including burnout [38]–[45], and a recent review of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) concludes that loving-kindness meditation (LKM) may be the most effective practice for increasing compassion [46]. Unfortunately, the duration of these interventions-often 8 to 15 weeks long- directly conflict with the limited time available to medical practitioners [45],[47]–[49]. There is a need for more effective and efficient interventions that require little time but still have the same positive affective consequences.

Our previous research suggests that even a few minutes of guided LKM practice directed toward a specific target can increase feelings of well-being and social connection toward that target as measured both implicitly and explicitly [50]. Yet this work has several limitations that make its implications for improving provider compassion unclear. First, it focused only on the influence of LKM on positive feelings toward a specific target, whereas providers must be able to evoke compassion toward a large number of patients in a wide array of circumstances. Second, although the study suggests that compassion can be evoked in a relatively short time using LKM, it is not clear whether LKM is more or less effective at inducing compassion or positive affect than other kinds of interventions. Here, we sought to address two important but open questions: can even a short compassion-inducing exercise (e.g., LKM) that is sufficiently time-effective (10 minutes) to fit into even the busiest of schedules produce reliable and meaningful changes in affective responding to others, even strangers? And two, how does LKM compare to other forms of affective interventions in its effectiveness?

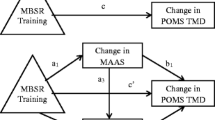

To answer these questions, we extended our prior work in two ways. First, we used the traditional form of LKM that did not involve focusing attention on a target in a photograph. We could therefore assess whether a short 10-minute LKM in its traditional form could still increase social connectedness. Second, in addition to a neutral comparison group (NEU), we included an active comparison group who completed a set of exercises designed to increase self-focused positive affect (PAI). This allowed us to test whether positive affect alone is sufficient to generate social connection [51], or whether LKM provides unique benefits.

In order to comprehensively evaluate social connection, the present study also used multiple measures of other-focused connection: mood indices, self-reported connection to photographs of strangers, and a semi-implicit measure of self-focus. We evaluated social connection with mood measures and self-reported feelings of closeness, similarity, connection, familiarity, and attractiveness to strangers in photographs. We evaluated self-focus with a semi-implicit measure to obtain a more objective measure of other-focus. We hypothesized that LKM would increase ratings of social connection (affect and ratings of strangers) and decrease self-focus more than both PAI and NEU.

Methods

Participants

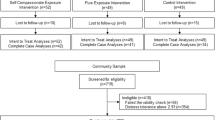

One hundred and thirty-four participants (59% female; mean age: 19 years, range 18–23; 38% Caucasian, 16% Asian, 8% Black, 13% Latino/Hispanic, 25% mixed-race or other), recruited from the undergraduate population at Stanford University, volunteered to take part in this study for course credit as part of their psychology course. Participants provided informed consent for the protocol approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. There were no a priori exclusion criteria, and all participants who volunteered were enrolled in the study.

Procedures

Study overview

This study sought to compare the effectiveness of a brief compassion-inducing intervention to two other conditions: a positive-affect manipulation that did not involve a focus on others (e.g. pride), and a non-affective neutral control condition. To accomplish this goal, we used a between-subjects manipulation with three groups, and a within-subjects measurement of changes pre- to post-intervention in several primary outcome measures. Primary outcome measures included composite measures of social and self-focused positive affect, negative affect, self-reported feelings of connection and compassion toward others, and a semi-implicit measure of self-focus. These measures were assessed once before and once after a brief aurally guided imagery task designed to evoke one of the three target affective states. Following assessment of all measures, participants were debriefed and paid. Below, we describe each aspect of the study procedures, as well as the dependent measures, in more detail.

Compassion manipulation

Once participants arrived in the lab, we used a random number generator to assign participants randomly to either a compassion intervention (LKM group, n = 46), a positive-affect control (PAI group, n = 44), or a non-affective neutral control condition (NEU group, n = 44). Participants were told that they were participating in a study on “meditation and cognitive function”. This cover story served to control for the demand characteristics and disguise the self-focus measures which, when embedded in other obviously cognition-related tasks, appeared as cognitive tasks. In particular, the questionnaires were interspersed with two traditional cognitive tasks - Stroop and verbal memory tasks – to ensure believability of the “cognitive function” cover story.

After seating the participants in a room with a computer and obtaining consent, experimenters explained to the participants that they would be filling out questionnaires, listening to a guided visualization exercise, and filling out additional questionnaires afterwards. Study duration was less than one hour.

The meditation exercises were preceded and followed by the mood probes and measures of social connection and self-focus. The questionnaires were interspersed with two traditional cognitive tasks (a memory and an attention task) to ensure believability of the “cognitive function” cover story. Below, we detail each of the measures that we used to assess pre- to post-manipulation changes in affective and social responding.

Social connection

Affect

To assess changes in affect accompanying the manipulation, and to examine whether changes in affect mediated changes in explicit or implicit social connectedness to others, participants indicated their current affect pre- and post-manipulation on a number of emotions. We utilized a shortened, adapted version of the Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS) [52]. Participants were given the following instructions: “Below are a series of emotion/state words. Using the scale provided, please rate how much you feel each emotion RIGHT NOW. Please indicate the extent to which you are currently experiencing the following emotion/state RIGHT NOW”. We created several affect composites from the affect probes to assess our primary outcome measures (general happiness, social connection, and self-focus): a socially connected positive affect composite (friendly, close to others, affection, loving, α = .81), a self-focused positive affect composite (proud, self-esteem, self-satisfaction, α = .60), and a negative affect composite (sad, angry, unhappy, bored, embarrassed, alone, α = .74).

Arousal often correlates with greater self-focus [53]–[55] and serves as an indicator of one’s decreasing sense or level of social connection to others [18]. We therefore added a 1-item explicit measure of arousal (“How active do you feel right now?”). Participants selected responses on a 7-point Likert rating scale (1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely).

Ratings of strangers

To assess social connection pre- and post-manipulation, we utilized a measure similar to the one we developed for our initial LKM study [50]. Participants indicated their subjective feelings of social connection on four variables - similarity, connectedness, familiarity, and attractiveness - toward the subject in each of three photographs using a 7-point Likert rating scale (1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely). The subjects in the three photographs were of varied ethnicity (Asian, White, Black). The gender of the photographs was matched to the participants so as to prevent a gender bias in the attractiveness ratings. Reliability analyses showed that the four social connectedness variables – similarity, connectedness, familiarity, and attractiveness – were closely correlated, warranting the creation of a positive social orientation composite with all four variables (α = .83).

Self-focus

To supplement explicit subjective responses and directly address demand characteristics, we also selected a semi-implicit measure of self-focus. Participants completed a shortened form of Wegner and Giuliano’s [55] pronoun-choice task as research has found it to be the most sensitive and well-established tool of self-focus [56]. In this measure, participants are asked to select the pronoun (e.g., I, he, our) they feel best fits a sentence. Selecting a majority of first person singular pronouns (e.g., I, me, my) indicates self-focused attention.

Interventions

Meditation instructions were presented over headphones and lasted about eight and a half minutes. All visualizations began with the instruction to close the eyes, relax, and take deep breaths. The LKM, PAI, and NEU visualizations were all closely matched for word count and duration. Please refer to the separate file for specific script details for each condition (see Additional file 1).

In the LKM condition, the introduction was followed by instructions to imagine two loved ones standing to either side of the participant and sending the participant their love. Then, participants were told to redirect these feelings of love and compassion first toward their loved ones, then towards acquaintances, and finally towards the whole world. Throughout the meditation, participants repeated a series of phrases wishing the targets health, happiness, and well-being.

The PAI condition was designed to be similar to LKM in terms of inducing positive mood (it was also matched for positive words) but different from LKM in terms of its emphasis on pride and uniqueness. We selected the PAI condition as an active control designed to control for mood (it was matched to the LKM condition for positive word count, see Additional file 1) and to address potential demand characteristics (by also inducing a positive state of mind). Participants brought to mind all of their academic, professional, artistic or athletic skills and repeated a series of phrases that reinforced the idea that they are unique and successful.

The NEU condition was designed to be as similar as possible to LKM and PAI in terms of relaxation effects, visualization exercise and duration yet remain affectively neutral. Participants visualized a number of neutral locations (e.g., a parking lot, a messy garage) in as much detail as they could.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS V22.0 [57]. Our primary analyses involved several 3 (Group: LKM, PAI, NEU) x 2 (Time: baseline, post-manipulation) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA). Dependent measures included both explicit and implicit measures of social connection, affect, and self-focus. Results are reported as significant if they passed an alpha-level of p < .05, two-tailed, and, where justified, followed up with between-group and paired t-tests to determine which condition or conditions drove a particular effect of interest. We also ran a separate set of analyses controlling for baseline differences in each measure using ANCOVA.

In our previous work on the effects of LKM on affective responding [50], we found effect sizes (assessed using Cohen’s d [58]) ranging from .65 – .7 for between-group t-tests comparing changes in mood and social responding, and effect sizes ranging from .7-.9 for within-subject tests of pre- to post-manipulation changes in affect for the LKM group. Power analysis revealed that for the minimum effect size observed in that study (d = .65), a sample size of at least 38 subjects per group is needed to obtain statistical power to detect between-group differences at the .80 level recommended by Cohen [58]. Similarly, a sample-size of at least 21 is required to detect within-subject changes at that level. A post-hoc power analysis indicated that with the sample-size collected in this study (minimum N = 44 per group), we have the power to detect differences with small to medium effect sizes at the .8 level (minimum detectable within-subjects d = .43, between-groups d = .6).

Results

Social connection

Affect

Group by time differences in other-focused positive affect were significant, F(2, 131) = 4.85, p < .01, ηp 2 = .07. As predicted, follow-up paired sample t-tests indicated that only LKM increased significantly, (Mpre = 4.00 SDpre = 1.15 Mpost = 4.41 SDpost = 1.14), t(45) = −3.83, p < .001), whereas PAI, t(44) = −1.93, p = .06, and NEU, t(43) = 0.85, p = .40, did not (PAI Mpre = 4.61 SDpre = 1.12, Mpost = 4.86 SDpost = 1.15; NEU Mpre = 4.36 SDpre = 1.12, Mpost = 4.26 SDpost = 1.19). The findings remained significant when controlling for any group differences in baseline F(2,130) = 4.56, p < .05.

Group by time differences in self-focused positive affect were also significant, F(2, 131) = 9.15, p = .00, ηp 2 = .12. As predicted, PAI increased significantly (Mpre = 3.95 SDpre = .82 Mpost = 4.55 SDpost = 1.12), t(43) = −4.04, p < .001), whereas neither LKM, t(45) = 0.48, p = .63, nor NEU, t(43) = 0.63, p = .53, were significant (LKM Mpre = 3.77 SDpre = 1.00, Mpost = 3.72 SDpost = 1.13; NEU Mpre = 4.08 SDpre = 1.13, Mpost = 4.00 SDpost = 1.14). The findings remained significant when controlling for any group differences in baseline F(2,130) = 9.87, p < .001.

There were no significant differences for negative affect, F(2, 131) = 0.24, p = .79, ηp 2 = .00, nor arousal, F(2, 130) = 1.27, p = .28, ηp 2 = .02. All three groups decreased significantly in negative mood. All three groups decreased in arousal. Although only PAI and NEU decreased significantly in arousal, the groups were not significantly different.

Ratings of strangers

Group by time differences in social connection were significant, F(2, 131) = 3.22, p < .05, ηp 2 = .05. As predicted, means derived from paired-sample t-tests suggest that LKM led to a significant increase in social connectedness (Mpre = 2.44, SDPre = .837; Mpost = 2.87, SDpost .99), t(45) = 4.26, p < .001, whereas PAI did not, (Mpre = 2.60, SDPre = 1.09; Mpost = 2.76 SDpost = 1.08), t(44) = −1.80, p = .08. Surprisingly, the NEU group experienced a significant increase in social connectedness, (Mpre = 2.50, SDpre = .84; Mpost = 2.67 SDpost = .91), t(43) = −2.78, p < .01. However, LKM increased significantly more than NEU, t(88) = 2.21, p < .05 (see Table 1 and Figure 1). The findings remained significant when controlling for any group differences in baseline F(2,130) = 3.00, p = .05.

Self-focus

Group by time differences in selection of singular first-person pronouns (I, me, my) in the Wegner and Giuliano [55] pronoun-choice task were significant, F(2, 131) = 4.78, p < .05, ηp 2 = .07. As hypothesized, follow up paired-sample t-tests showed that the LKM group selected significantly fewer self-focused pronouns post-manipulation, (Mpre = 3.96 SDpre = 1.38, Mpost = 2.87 SDpost = 1.51) t(45) = 3.99, p < .001, whereas there was no significant change for the PAI, t(44) = 1.39, p = .17, or the NEU group, t(43) = −0.69, p = .50 (PAI Mpre = 3.75 SDpre = 1.57, Mpost = 3.27 SDpost = 2.22; NEU Mpre = 4.18, SDpre = 1.63, Mpost = 4.34 SDpost = 2.11) (see Table 1 and Figure 1). The findings remained significant when controlling for any group differences in baseline F(2,130) = 6.45, p < .01.

Discussion and conclusions

Implications for decreasing burnout

Given the extent of burnout and stress in the medical field [11],[59], the desire on the part of providers, medical staff, and patients for more compassionate interactions [20],[24],[29] and the stress-buffering and health-promoting impact of compassion [32],[35], it is imperative that healthcare providers avail themselves of tools to help decrease burnout and increase compassion. While efforts are being made to reduce stress in medical schools [60], the millions of providers already in practice are in need of tools that are beneficial and time-effective.

In this study, we extended previous work to demonstrate that a single 10-minute session of LKM practice can increase feelings of social connection and decrease self-focus among novice meditators. LKM is thus a tool that can potentially be applied on a short break and by nearly anyone. In particular, LKM can, in less than 10 minutes, increase people’s feelings of social connection and ratings of closeness to strangers (including feelings of connection, similarity, familiarity, and attraction). Moreover, the decrease in self-focus observed in the present study is associated with studies of prosocial states such as empathy and compassion [61],[62]. This may explain why LKM appears to create a feeling of “warm glow” around others, as reflected by increased perception of others as not only more similar and connected to oneself but also as more familiar and attractive. Speculatively, this warm glow could aid medical practitioners in taking a more compassionate approach to patients. LKM is thus a time- and cost-effective tool that healthcare providers can utilize to increase feelings of well-being as well as other-oriented compassion.

Given the focus of the Journal of Compassionate Healthcare on healthcare providers, these findings are discussed in the medical context alone. However, it is important to note that the benefits of a short LKM intervention can be applied to any personal or organizational setting - education, corporate, governmental and even military. Given the impact of stress on health and well-being, there is an increasing need for short, pragmatic interventions that produce an immediate impact and can be easily implemented by novice or experienced practitioners.

Implications for improving patient care

A compassionate workplace is characterized by strong relationships among employees and improved work performance. In a longitudinal study at a healthcare facility, a culture of compassionate love was associated with reduced employee emotional exhaustion and absenteeism, and with increased work engagement (i.e., teamwork and satisfaction) [63]. In extensive research conducted in other types of workplace settings, compassionate, friendly, and supportive co-workers build higher-quality relationships with colleagues [64]. As a consequence, they boost coworkers’ productivity and engagement levels [30],[65], increase coworkers’ feelings of social connection [66], commitment to the workplace [67], and levels of workplace engagement [65]. The impact of social support and kindness trickles horizontally as well as vertically. When a manager behaves more prosocially, there is less voluntary employee turnover [68].

Greater satisfaction with the workplace has implications for quality of patient care. Provider-patient interactions have a significant impact on patient healthcare outcomes [69]. In a study of providers, nurses, and technologists, positive affect was positively related to interpersonal job performance, which includes “conveying feelings of empathy, warmth and respect for the patient” [70]. Providers more satisfied with their jobs are more likely to show better service attitudes, and their patients are more satisfied and likely to utilize the services in the future [71]. Indeed, positive affect, a natural outcome of higher job satisfaction, promotes more careful, thorough, and efficient decision-making processes, suggesting that positive affect indirectly effects productivity and higher quality of care [72]. It is no surprise that nurses in better work environments have more satisfied patients [73].

Limitations and future directions

Although our study has numerous strengths, including two active control groups, randomization, and a range of outcome variables (self-reported affect, positive social orientation, and self-focus), it also has some limitations that restrict the conclusions we can draw from it alone. For example, our study pointed to the positive effects of LKM, but with a sample restricted to a college population. Future research should assess generalizability to healthcare providers, in particular, implementation in healthcare settings, and compare the short-term effects of a 10-minute intervention with the impacts of more involved and time-intensive LKM courses. Future research will also be needed to determine whether continued practice with a short meditation exercise like the one presented here has similar effects to long-term LKM practice on increased positive affect [51] and empathic responding to others’ suffering [74].

Future work will also be needed to explore a methodological limitation of the current study. The observation that LKM reduced self-focused attention may be due simply to the fact that LKM explicitly directs attention outward (on another person) for 50% of the time during meditation. PAI, on the other hand, directs attention to oneself for 100% of the time. Thus, the reduced self-focus observed here could be due not to affective consequences of meditation, but simply to the act of attending outward. Although we did not observe an effect of the outwardly-focused NEU instructions, further research will be needed to determine the active ingredients of successful compassion induction and reduced self-focus.

The growing body of compassion-inducing meditations such as LKM on psychological well-being raises the question of mechanism, and future studies could help to determine the active ingredients in LKM’s benefits (e.g., through changes in brain activation). For example, research shows that stress and anxiety naturally heighten self-focus [19]. Perhaps visualizing one’s affection for others turns attention away from the self, thereby potentially reducing self-focused negative affect and decreasing psychological distress [75]. Alternatively, LKM may exert its effects through cognitive reappraisal [76]. The words and phrases used in the meditation may help restructure cognitive interpretations to be more positive and kind towards others. Finally, by generating affectionate feelings for others, LKM may activate nurturance pathways in the brain and psychophysiology [77]. Understanding the causal mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of LKM is not just of purely theoretical interests, but could help identify whether personality and psychological factors determine enjoyment of and beneficial effects from LKM.

Given the low levels of well-being, social connection, and compassion in healthcare settings, as well as the demanding time constraints of healthcare providers’ schedules, there is a need to offer time-effective solutions to healthcare providers. Furthermore, given the numerous benefits of increasing compassion for healthcare providers and patients, short practical interventions may be the only solution. This study found that even a single 10-minute session of LKM increased other-focused affect and orientation, and decreased self-focus. LKM thus shows promise as a viable practice for improving well-being and compassion in healthcare providers.

Additional file

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- LKM:

-

Loving-kindness meditation

- NEU:

-

Neutral meditation visualization condition

- PAI:

-

Non-compassion positive affect induction condition

- PANAS:

-

Positive and negative affect scale

References

Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Barrett BP, Chewning BA, Craig BM, Niu M: Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med 2009, 41: 494–501.

Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV: The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof 2004, 27: 237–251. 10.1177/0163278704267037

Cramer J, Rosenheck R, Kirk G, Krol W, Krystal J: Medication compliance feedback and monitoring in a clinical trial: predictors and outcomes. Value Health 2003, 6: 566–573. 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.65269.x

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS: Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med 2011, 86: 359–364. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1

Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, Wang X, Rossi G, Hojat M, Gonnella JS: The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications. Acad Med 2012, 87: 1243–1249. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf

Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR: Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol 1999, 17: 371–379.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD: Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Acad Med 2006, 81: 374–384. 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00010

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, Durning S, Moutier C, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD: Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008, 149: 334–341. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

Cohen JS, Leung Y, Fahey M, Hoyt L, Sinha R, Cailler L, Ramchandar K, Martin J, Patten S: The happy docs study: a Canadian Association of Internes and Residents well-being survey examining resident physician health and satisfaction within and outside of residency training in Canada. BMC Res Notes 2008, 1: 105. 10.1186/1756-0500-1-105

Rutledge T, Stucky E, Dollarhide A, Shively M, Jain S, Wolfson T, Weinger MB, Dresselhaus T: A real-time assessment of work stress in physicians and nurses. Health Psychol 2009, 28: 194–200. 10.1037/a0013145

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J, Oreskovich MR: Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012, 172: 1377–1385. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL: Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002, 136: 358–367. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008

Olds DM, Clarke SP: The effect of work hours on adverse events and errors in health care. J Saf Res 2010, 41: 153–162. 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.02.002

Dorrian J, Tolley C, Lamond N, van den Heuvel C, Pincombe J, Rogers AE, Drew D: Sleep and errors in a group of Australian hospital nurses at work and during the commute. Appl Ergon 2008, 39: 605–613. 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.012

Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C: Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med 2011, 86: 996–1009. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

Nunes P, Williams S, Sa B, Stevenson K: A study of empathy decline in students from five health disciplines during their first year of training. Int J Med Educ 2011, 2: 12–17. 10.5116/ijme.4d47.ddb0

Wilson SE, Prescott J, Becket G: Empathy levels in first- and third-year students in health and non-health disciplines. Am J Pharm Educ 2012, 76: 24. 10.5688/ajpe76224

Eysenck MW: Anxiety and cognition: a unified theory. Psychology Press, East Sussex; 1997.

Mor N, Winquist J: Self-focused attention and negative affect: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2002, 128: 638–662. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.638

Dignity Health: Dignity Health survey finds majority of Americans rate kindness as top factor in quality health care. ᅟ ᅟ, ᅟ: [http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/11/13/ca-dignity-health-idUSnBw135348a+100+BSW20131113]

Petit-Zeman S: Where has the humanity gone? J R Soc Med 2006, 99: 647. 10.1258/jrsm.99.12.647

Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM: The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice: lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med 1994, 154: 1365–1370. 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420120093010

Moore PJ, Adler NE, Robertson PA: Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med 2000, 173: 244–250. 10.1136/ewjm.173.4.244

Lown BA, Rosen J, Marttila J: An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011, 30: 1772–1778. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0539

Bru E, Svebak S, Mykletun RJ, Gitlesen JP: Back pain, dysphoric versus euphoric moods and the experience of stress and effort in female hospital staff. Pers Ind Diff 1997, 22: 565–573. 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00227-9

Sarinopoulos I, Hesson AM, Gordon C, Lee SA, Wang L, Dwamena F, Smith RC: Patient-centered interviewing is associated with decreased responses to painful stimuli: an initial fMRI study. Patient Educ Couns 2013, 90: 220–225. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.021

Lamothe M, Boujut E, Zenasni F, Sultan S: To be or not to be empathic: the combined role of empathic concern and perspective taking in understanding burnout in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2014, 15: 15. 10.1186/1471-2296-15-15

Baumeister RF, Leary MR: The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 1995, 117: 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke SP, Vargas D: Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care 2004,42(2 Suppl):II57-II66.

Lilius JM, Worline MC, Maitlis S, Kanov J, Dutton JE, Frost P: The contours and consequences of compassion at work. J Organ Behav 2008, 29: 193–218. 10.1002/job.508

Evans O, Steptoe A: Social support at work, heart rate, and cortisol: a self-monitoring study. J Occup Health Psychol 2001, 6: 361–370. 10.1037/1076-8998.6.4.361

Poulin MJ, Brown SL, Dillard AJ, Smith DM: Giving to others and the association between stress and mortality. Am J Public Health 2013, 103: 1649–1655. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300876

Cosley BJ, McCoy SK, Saslow LR, Epel ES: Is compassion for others stress buffering? Consequences of compassion and social support for physiological reactivity to stress. J Exp Soc Psychol 2010, 46: 816–823. 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.008

Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM: Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychol Sci 2003, 14: 320–327. 10.1111/1467-9280.14461

Konrath S, Fuhrel-Forbis A, Lou A, Brown S: Motives for volunteering are associated with mortality risk in older adults. Health Psychol 2012, 31: 87–96. 10.1037/a0025226

Epstein RM, Krasner MS: Physician resilience: What it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med 2013, 88: 301–303. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280cff0

Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD: How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. JGIM 2007, 22: 177–183. 10.1007/s11606-006-0039-6

Arch JJ, Craske MG: Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther 2006, 44: 1849–1858. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007

Asmundson GJG, Stein MB: Vagal attenuation in panic disorder: an assessment of parasympathetic nervous system function and subjective reactivity to respiratory manipulations. Psychosom Med 1994, 56: 187–193. 10.1097/00006842-199405000-00002

Hofmann SG, Grossman P, Hinton DE: Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clin Psychol Rev 2011, 31: 1126–1132. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003

Hoge EA, Chen MM, Orr E, Metcalf CA, Fischer LE, Pollack MH, DeVivo I, Simon NM: Loving-kindness meditation practice associated with longer telomeres in women. Brain Behav Immun 2013, 32: 159–163. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.04.005

Kaushik RM, Kaushik R, Mahajan SK, Rajesh V: Effects of mental relaxation and slow breathing in essential hypertension. Complement Ther Med 2006, 14: 120–126. 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.11.007

Marchand WR: Mindfulness meditation practices as adjunctive treatments for psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2013, 36: 141–152. 10.1016/j.psc.2013.01.002

Sakakibara M, Hayano J: Effect of slowed respiration on cardiac parasympathetic response to threat. Psychosom Med 1996, 58: 32–37. 10.1097/00006842-199601000-00006

Salkovskis PM, Jones DR, Clark DM: Respiratory control in the treatment of panic attacks: replication and extension with concurrent measurement of behavior and pCO2. Br J Psychiatry 1986, 148: 526–532. 10.1192/bjp.148.5.526

Boellinghaus I, Jones FW, Hutton J: The role of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation in cultivating self-compassion and other-focused concern in health care professionals. Mindfulness 2012, ᅟ: ᅟ. Available from: . http://self-compassion.org/UTserver/pubs/MeditationSelfCompassion.pdf

Levy DM, Wobbreck JO, Kaszniak AW, Ostergren M: The effects of mindfulness meditation training on multitasking in a high-stress information environment. Proc Graphics Interface 2012, ᅟ: 45–52.

Pipe TB, Bortz JJ, Dueck A, Pendergast D, Buchda V, Summers J: Nurse leaders mindfulness meditation program for stress management. J Nurs Adm 2009, 39: 130137. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31819894a0

Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, Cordova M: Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. Int J of Stress Manag 2005, 12: 164–176. 10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164

Hutcherson CA, Seppala EM, Gross JJ: Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion 2008, 8: 720–724. 10.1037/a0013237

Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM: Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Pers Soc Psychol 2008, 95: 1045–1062. 10.1037/a0013262

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988, 54: 1063–1070. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Gur RC, Sackeim HA: Self-deception: a concept in search of a phenomenon. J Pers Soc Psychol 1979, 37: 147–169. 10.1037/0022-3514.37.2.147

Paulus PB, Annis AB, Risner HT: An analysis of the mirror-induced objective self-awareness effect. Bull Psychon Soc 1978, 12: 8–10. 10.3758/BF03329609

Wegner DM, Giuliano T: Arousal-induced attention to self. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980, 38: 719–726. 10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.719

Silvia PJ, Abele AE: Can positive affect induce self-focused attention? Methodological and measurement issues. Cogn Emotion 2002, 16: 845–853. 10.1080/02699930143000671

IBM Corp: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY; 2013.

Cohen J: A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992,112(1):155–159. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Neville K, Cole DA: The relationships among health promotion behaviors, compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in nurses practicing in a community medical center. J Nurs Adm 2013, 43: 348–354. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182942c23

Slavin SJ, Schindler DL, Chibnall JT: Medical student mental health 3.0: improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad Med 2014, 89: 573–577. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000166

Batson CD: The Altruism Question: Toward a Social Psychological Answer. Erlbaum, New Jersey; 1991.

Cialdini RB, Brown SL, Lewis BP, Luce C, Neuberg SL: Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997, 73: 481–494. 10.1037/0022-3514.73.3.481

Barsade SG, O’Neill OA: What’s love got to do with it? A longitudinal study of the culture of companionate love and employee and client outcomes in the long-term care setting. Adm Sci Q 2014, ᅟ: 1–48.

Dutton JE, Roberts LM, Bednar J: Pathways for positive identity construction at work: four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Acad Manag Rev 2010, 35: 265–293. 10.5465/AMR.2010.48463334

Bakker AB: An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr Dir in Psychol Sci 2011, 20: 265–269. 10.1177/0963721411414534

Kanov JM, Maitlis S, Worline MC, Dutton JE, Frost PJ, Lilius JM: Compassion in organizational life. Am Behav Sci 2004, 47: 808–827. 10.1177/0002764203260211

Lilius JM, Kanov J, Dutton JE, Worline MC, Maitlis S: Compassion Revealed: What we Know About Compassion at Work (and Where we Need to Know More). In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. 1st edition. Edited by: Spreitzer GM, Cameron KS. Oxford University Press, New York; 2011:273–287.

Barsade SG, Gibson DE: Why does affect matter in organizations? Acad Manag Perspect 2007, 21: 36–59. 10.5465/AMP.2007.24286163

Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H: The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2014, 9: ᅟ. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101191

Stewart W, Barling J: Daily work stress, mood and interpersonal job performance: a mediational model. Work Stress 1996, 10: 336–351. 10.1080/02678379608256812

Tzeng H-M, Yang CH: An exploratory study in the relationship between outpatient satisfaction with service attitudes and health care providers’ job satisfaction in Taipei public hospitals. Asia Pacific Manag Rev 2005, 10: 17–28.

Isen AM: An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: theoretical issues with practical implications. J Consumer Psychol 2001, 11: 75–85. 10.1207/S15327663JCP1102_01

Kutney-Lee A, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Flynn L, Neff DF, Aiken LH: Nursing: a key to patient satisfaction. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009, 28: 669–677. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w669

Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis J, Johnstone T, Davidson RJ: Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: effects of meditative expertise. PLoS One 2008, 3: e1897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001897

Carson JW, Keefe FJ, Lynch TR, Carson KM, Goli V, Fras AM, Thorp SR: Loving-kindness meditation for chronic low back pain: results from a pilot trial. J Holist Nurs 2005, 23: 287–304. 10.1177/0898010105277651

Gross JJ, John OP: Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003, 85: 348–362. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL: Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2010, 30: 849–864. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Rika Onizuka for helping with experimental data collection and to Maaheem Akhtar and Atsuko Iwasaki for contributing to the literature review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EMS conducted the experiment and drafted the article. CAH offered theoretical and experimental input and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. DTHN participated in the drafting and revisions of the manuscript. JRD contributed to the manuscript. JJG provided essential guidance on the development of the experiment and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Seppala, E.M., Hutcherson, C.A., Nguyen, D.T. et al. Loving-kindness meditation: a tool to improve healthcare provider compassion, resilience, and patient care. J of Compassionate Health Care 1, 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-014-0005-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-014-0005-9