Abstract

Background

Critically ill patients develop atrophic muscle failure, which increases morbidity and mortality. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is activated early in sepsis. Whether IL-1β acts directly on muscle cells and whether its inhibition prevents atrophy is unknown. We aimed to investigate if IL-1β activation via the Nlrp3 inflammasome is involved in inflammation-induced atrophy.

Methods

We performed an experimental study and prospective animal trial. The effect of IL-1β on differentiated C2C12 muscle cells was investigated by analyzing gene-and-protein expression, and atrophy response. Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by cecum ligation and puncture surgery in Nlrp3 knockout and wild type mice. Skeletal muscle morphology, gene and protein expression, and atrophy markers were used to analyze the atrophy response. Immunostaining and reporter-gene assays showed that IL-1β signaling is contained and active in myocytes.

Results

Immunostaining and reporter gene assays showed that IL-1β signaling is contained and active in myocytes. IL-1β increased Il6 and atrogene gene expression resulting in myocyte atrophy. Nlrp3 knockout mice showed reduced IL-1β serum levels in sepsis. As determined by muscle morphology, organ weights, gene expression, and protein content, muscle atrophy was attenuated in septic Nlrp3 knockout mice, compared to septic wild-type mice 96 h after surgery.

Conclusions

IL-1β directly acts on myocytes to cause atrophy in sepsis. Inhibition of IL-1β activation by targeting Nlrp3 could be useful to prevent inflammation-induced muscle failure in critically ill patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A major contributor of intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired weakness (ICUAW) is a severe and disabling muscle atrophy leading to loss in strength and mass [1–4]. ICUAW is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and has a significant impact on healthcare systems [5, 6]. Sepsis and systemic inflammation are major risk factors for ICUAW [7, 8]. Importantly, inflammation and acute-phase response occur early and directly in muscle and affect disease progression in ICUAW. Recently, others and we reported an imbalanced protein homeostasis caused by increased protein degradation and reduced protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle [4, 9–11]. Muscular-motor protein breakdown, especially myosin heavy chain (MyHC), via the protein degrading ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), is a prominent feature of muscle atrophy [1, 4, 10–13]. The E3 ligase, muscle RING finger (MuRF) 1 (TRIM63), and F-box protein atrogin 1 (FBXO32) are increased in muscle during atrophy and mediate degradation of structural proteins [4, 10]. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is one of the most activated cytokines in sepsis [14–20]. In muscle, IL-1β increases MuRF1 and atrogin 1 expression implicating a function in atrophy [21–23]. However, if IL-1β directly causes muscle atrophy in sepsis and if inhibition of IL-1β prevents this response is unknown. IL-1β production and secretion requires three consecutive steps that are tightly controlled, namely expression, cleavage, and secretion. Whereas inflammatory cytokines increase expression of pro-IL-1β, which is the inactive proform of IL-1β, its conversion to IL-1β, and its secretion is mediated by caspase-1 activating inflammasomes [14, 24–28]. Inflammasomes are multi-protein complexes of the innate immune system [29] and involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis [30]. Cytoplasmic receptors of the nucleotide binding domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family are key components of the inflammasome, of which the best characterized NLR is NLRP3 [31, 32]. The NLRP3 inflammasome regulates maturation and secretion of IL-1β [32]. IL-1β signal transduction occurs via the IL-1 receptor, which is associated with IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) that activates the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) [33]. NLRP3 is contained in muscle, and its activity is increased in myopathies [34]. However, the function of NLRP3 and IL-1β in ICUAW is unknown. We tested the hypothesis that IL-1β, depending on the Nlrp3 inflammasome, contributes to inflammation-induced atrophy in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Animal model

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, were approved by the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin, Germany (G207/13, G129/12), and followed the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) and the current version of German Law on the Protection of Animals. Nlrp3 knockout (KO) mice were kindly provided by Aubry Tardivel and Nicolas Fasel (University of Lausanne) [35]. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery was performed to induce polymicrobial sepsis in 12- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO or wild-type (WT) mice as recently described [36–38]. Sham mice were treated identically except for the ligation and puncture of the cecum. Mice were sacrificed 96 h after surgery. For more information, see Additional file 1.

Molecular and cell biology analysis

For detailed information about quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), western blotting, immunostaining, and cell culture, see Additional file 1. Measurements of serum IL-1β were performed by using the Mouse ELISA Kit for IL-1β (Abcam, ab100704) according to the manufacturers’ protocol.

Statistical tests

All experiments were performed independently and at least three times using biological triplicates each. All qRT-PCR gene expression data from mouse and cell culture samples was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc correction (Tukey’s post-comparison test). Paired t test was used to study the distribution of myotube diameter in C2C12 myotubes. Survival curves were compared with a Mantel-Cox test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in bar plots. Plots and statistics calculation were done by using the GraphPad Prism® 6 program (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), Adobe Illustrator CS6, version 16.0.0, and Photoshop CS6, version 13.0. The documentation of immunofluorescence and histological staining results was performed with a Leica fluorescence microscope using Leica cameras (DFC 360 FX and DFC 425) and the LAS.AF software (version: 2.4.1 build 6384 and the LAS3.1 software (version 2.5.0.6735).

Results

IL-1β induces myocyte atrophy in vitro

Recently, we showed that inflammation and acute-phase response participates in the pathogenesis of ICUAW in patients [10]. However, whether IL-1β is synthesized in muscle and whether Nlrp3-mediated IL-1β maturation is involved in inflammation-induced atrophy was unknown. We performed qRT-PCR to investigate if sepsis increases Il1b or Nlrp3 expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris or tibialis anterior muscle of mice and found that sepsis induced Il1b and Nlrp3 expression in both muscles (Additional file 2A, B). Il6 expression was also induced. These data indicate that IL-1β and Nlrp3 are contained and activated in muscles during sepsis.

To investigate if the IL-1β signaling pathway is contained and active in myocytes, we analyzed cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of IL-1 receptor type I (IL-1R1) associated kinase 1 (IRAK-1) in C2C12 muscle cells. C2C12 myoblasts were originally isolated from wild-type mice [39] and selected for its ability to differentiate to myotubes expressing characteristic muscle proteins [40]. Others [41–43] and we [36, 38, 44] have used this cell line earlier to investigate mechanisms of inflammation-induced myocyte atrophy. Using immunocytochemistry, we found that 30 min of IL-1β treatment resulted in an increased cytoplasmic-to-nuclear shift of IRAK-1 in C2C12 myocytes (Fig. 1a) indicating that the IL-1β pathway is active in myocytes. Since IL-1β mediates its effects via NF-κB in non-myocytes, a luciferase reporter assay was used to test if this response also occurs in myocytes. The same assay performed in HeLa cells was used as positive control. IL-1β treatment induced the NF-κB promoter in muscle and non-muscle cells (Fig. 1b), indicating that IL-1β activates NF-κB dependent signaling events in muscle cells. To test if IL-1β induces its target genes in myocytes, we treated C2C12 myotubes with recombinant IL-1β for different time points and quantitated Il6 expression (Fig. 1c). IL-1β induced Il6 and Nlrp3 expression in myocytes after 2 h of treatment (Fig. 1c, d). Together, these data indicate that the IL-1β pathway is functional in myocytes. To investigate if IL-1β induces myocyte atrophy, we treated C2C12 myotubes with increasing amounts of recombinant IL-1β and vehicle, respectively, for 72 h and measured myotube diameters. IL-1β treatment caused a significant reduction of myotube diameters after 72 h (Fig. 1e). Frequency distribution histograms of myotube diameters showed a dose-dependent increase in the number of thinner myotubes resulting in a leftward shift of the histogram and a dose-dependent decrease in mean myotube diameters after 72 h of treatment (Fig. 1f, h). Dexamethasone (Dexa), which was used as positive control, resulted in myotube atrophy after 72 h (Fig. 1e, g, h).

The IL-1β signaling pathway is contained and active in C2C12 myocytes. a C2C12 muscle cells were treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or vehicle for 30 min and 1 h. Immunocytochemistry with anti-IRAK1 antibody shows cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of IRAK1 in response to IL-1β after 30 min. Nuclei were stained in blue (DAPI). Scale bar = 50 μm. b Synthetic luciferase reporters with multimerized NF-κB sites (NF-κB-Luc) were transfected into C2C12 (b, left panel) and HeLa (b, right panel) cells, together with LacZ as transfection control. Cells were treated with recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. n = 3. c, d C2C12 cells were differentiated for 8 days and treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for different time points as indicated. qRT-PCR analysis of Il6 and Nlrp3. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. All data are reported as fold change ± SEM. e–h IL-1β increases Nlrp3 expression and induces atrophy in differentiated C2C12 myocytes in vitro. C2C12 cells were differentiated for 8 days and treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10, 20, and 50 ng/ml) for 72 h. Dexamethasone (10 μM/ml) treatment was used as atrophy control. e Representative light microscopy pictures. Scale bar = 250 μm. f, g Frequency distribution histograms of cell width of IL-1β (10, 20, and 50 ng/ml) and dexamethasone-treated myotubes, as indicated, compared to vehicle-treated myotubes, n = 100 cells per condition. h Mean myotube width. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001

Because a reduction in MyHC proteins is consistently observed in inflammation-induced atrophy [1, 10], we investigated if IL-1β causes a reduction in MyHC protein. C2C12 myotubes were treated with recombinant IL-1β and vehicle, respectively, for 72 h and Western blot was performed. Indeed, IL-1β decreased fast and slow MyHC protein contents (Fig. 2a). As expected, Dexa treatment caused a reduction in slow and fast MyHC contents after 72 h (Fig. 2a). Recently, we reported that inflammation-induced atrophy is caused by a dysregulation in protein homeostasis with decreased MyHC expression and increased UPS-dependent MyHC degradation [10]. Therefore, we investigated if IL-1β causes a reduction in MyHC expression. C2C12 myotubes were treated with IL-1β and vehicle, respectively, for 24 h and Myh2, 4, and 7 expression, encoding fast/type IIa, fast/type IIb and slow/type I MyHC, respectively, was quantitated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2b). IL-1β treatment led to a decreased Myh2, Myh4, and Myh7 expression after 24 h; whereas Dexa led to an increased Myh4 and Myh7 but not Myh2 expression (Fig. 2b). To test if IL-1β activates atrophy gene expression involved in MyHC degradation, we treated C2C12 myotubes with IL-1β for 2 h and quantitated Trim63 and Fbxo32 expression by qRT-PCR. IL-1β significantly increased Trim63 and Fbxo32 expression, indicating that MuRF1 and atrogin 1 are involved in IL-1β-induced atrophy. Likewise, Dexa treatment increased Trim63 and Fbxo32 expression in myocytes (Fig. 2c). These data indicate that IL-1β causes a disturbed protein homeostasis contributing to IL-1β mediated atrophy.

IL-1β treatment induces Trim63 (MuRF1) and Fbxo32 (atrogin 1) gene expression and reduces slow and fast myosin heavy chain (MyHC) in C2C12 myotubes. a C2C12 cells were differentiated for 8 days and treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 72 h. Dexamethasone (10 μM/ml) treatment was used as atrophy control. Western blot analysis with anti-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) slow and anti-MyHC-fast antibody. n = 3. GAPDH was used as loading control. b C2C12 cells were differentiated for 8 days and treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Dexamethasone (10 μM/ml) treatment was used as atrophy control. qRT-PCR analysis of myosin heavy chain (Myh) 2, Myh4, and Myh7 expression. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. c C2C12 cells were differentiated for 8 days and treated with human recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 2 h. Dexamethasone (10 μM/ml) treatment was used as atrophy control. qRT-PCR analysis of Trim63 (MuRF1) and Fbxo32 (atrogin 1) expression. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

Nlrp3 KO mice are protected against inflammation-induced atrophy

At baseline, Nlrp3 KO were indistinguishable from WT mice and did not differ in body, liver, spleen, or skeletal muscle weights normalized to tibia length (Additional file 3A–C). To investigate whether or not Nlrp3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β activation affects inflammation-induced atrophy, we subjected male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice to CLP (Nlrp3 KO, n = 27; WT, n = 33) or sham surgery (Nlrp3 KO, n = 11; WT, n = 16), respectively. Compared to WT mice, significantly less Nlrp3 KO mice died after 96 h after CLP surgery (57.6 vs. 29.6%; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Septic WT mice showed a reduction in body and liver weight and no change in spleen weight (Fig. 3b; Additional file 4A, B). In contrast, Nlrp3 KO did not lose body or liver weight, while spleen weight increased in these mice during sepsis (Fig. 3b; Additional file 4A, B). We investigated if absence of Nlrp3 affects muscular cytokine expression in sepsis. At baseline, Il6 expression was not different between Nlrp3 KO and WT in gastrocnemius/plantaris and tibialis anterior (Additional file 5A). CLP did not or only marginally induce muscular Il6 expression in Nlrp3 KO compared to WT (Fig. 3c, d). Also, Il1b expression was not different between Nlrp3 KO and WT at baseline, and its expression was blunted in muscles of CLP-treated Nlrp3 KO compared to WT mice (Additional file 6A, B). CLP induced Nlrp3 expression in WT but not in Nlrp3 KO (Additional file 6C, D). Since conversion of pro-IL-1β to IL-1β depends on an intact Nlrp3 inflammasome [14, 24, 25], we quantitated IL-1β cytokine levels in the serum of Nlrp3 KO and WT. Already at baseline, IL-1β serum levels were reduced in Nlrp3 KO compared to WT (Additional file 6E). CLP significantly induced IL-1β serum levels in WT. This induction in IL-1β serum levels was greatly reduced in Nlrp3 KO (Additional file 6F). These data indicate that in sepsis muscular Il1b and Il6 expression depend on Nlrp3.

Nlrp3 KO mice have a survival benefit and do not lose body or muscle weight during 96 h of sepsis. Twelve- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery. a Survival curves show an improved survival of Nlrp3 KO compared to WT mice following CLP surgery. All sham mice survived to the experimental end point. Survival analysis was performed with Log-Rank-test; WT sham vs. WT CLP: p ≤ 0.001, (circle); Nlrp3 KO sham vs. Nlrp3 KO CLP: p ≤ 0.05, (number sign); WT CLP vs. Nlrp3 KO CLP: p ≤ 0.05 (section sign). The numbers of animals in each experimental group are indicated in the figure. b Body weight at 96 h after surgery. CLP-treated Nlrp3 KO (n = 16); sham Nlrp3 KO (n = 8), WT CLP (n = 12), WT sham (n = 13). c, d qRT-PCR analysis of Il6 expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris and tibialis anterior muscles of WT sham (n = 5), WT CLP (n = 9), Nlrp3 KO sham (n = 5), and Nlrp3 KO CLP (n = 6) mice. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. e, f Weights of the skeletal muscles, e gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP), and f tibialis anterior (TA) determined at 96 h after surgery. CLP treated Nlrp3 KO (n = 16); sham Nlrp3 KO (n = 8), WT CLP (n = 12), WT sham (n = 13). All weights were normalized to tibia length and expressed as percent-wise change compared to the respective sham group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ns = not significant

Compared to WT sham, WT CLP mice showed a significant reduction in the weights of all muscles investigated 96 h after surgery. In contrast, the reduction of muscle mass of Nlrp3 KO CLP compared to Nlrp3 KO sham mice was less severe (Fig. 3e, f, Additional file 4C, D). These data indicate that Nlrp3 KO mice are protected against inflammation-induced atrophy. Since inflammation-induced atrophy predominantly affects fast-twitch fibers in critically ill patients [10], we analyzed atrophy of fast/type II fibers in gastrocnemius/plantaris and tibialis anterior muscles of Nlrp3 KO and WT after CLP. The histological pictures show that myofibers of WT but not of Nlrp3 KO CLP atrophied during sepsis (Fig. 4a). Accordingly, frequency distribution histograms of the myocyte cross sectional areas (MCSA) showed an increased number of smaller fast/type II fibers in both muscles of septic WT but not Nlrp3 KO leading to a leftward shift of the distribution curve (Fig. 4b). This atrophic response was attenuated in Nlrp3 KO compared to WT following sepsis as indicated by a less pronounced reduction in mean MCSA in septic Nlrp3 KO (Fig. 4b). These data indicate Nlrp3 contributes to fast/type II fiber atrophy in sepsis.

Nlrp3 KO mice are protected from inflammation-induced muscle atrophy. 12–16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery. a H&E and ATPase stain of histological cross sections from gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscle from sham and CLP-operated WT and Nlrp3 KO mice at 96 h after surgery, as indicated. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Quantification of fast/type II myofiber cross-sectional area (MCSA) in GP and TA from transverse sections stained with metachromatic ATPase dye assay (as shown in a). MCSA was determined by using ImageJ software. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001

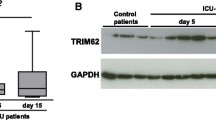

To test if inflammatory atrophy was accompanied by a reduction in MyHC, Western blot analysis was performed and showed that sepsis caused a reduction of slow and fast MyHC protein in gastrocnemius/plantaris and tibialis anterior of WT but not Nlrp3 KO (Fig. 5a). To elucidate if decreased myosin content was due to a reduction in MyHC gene expression, we quantitated Myh2, 4 and 7 by qRT-PCR. Inflammation caused a significant reduction in Myh2 and Myh7 gene expression in WT gastrocnemius/plantaris muscle (Fig. 5b). In contrast, Myh2 and Myh7 expression increased in Nlrp3 KO gastrocnemius/plantaris muscle during inflammation (Fig. 5b). Inflammation did not affect Myh4 gene expression. In the tibialis anterior muscle, Myh2 gene expression was regulated with the same trend as in gastrocnemius/plantaris, whereas Myh4 and Myh7 did not show a significant regulation (Additional file 7). To test if decreased myosin content was correlated with increased atrogene expression, we quantitated Trim63 and Fbxo32 expression in the muscle. Indeed, Trim63 and Fbxo32 expression were significantly increased in septic WT but remained unchanged in Nlrp3 KO muscles (Fig. 5c–f). Western blot analysis showed that MuRF1 protein expression was increased in gastrocnemius/plantaris of WT CLP but not in Nlrp3 KO CLP (Fig. 5a). These data indicate that decreased Myh gene expression and its increased degradation contribute to inflammation-induced atrophy.

Disturbed muscular protein homeostasis in sepsis is blunted in Nlrp3 KO mice. Twelve- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery. a Western blot analysis with anti-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) slow and anti-MyHC fast antibody and anti-MuRF1 antibody GAPDH was used as loading control; n = 3. b qRT-PCR analysis of myosin heavy chain (Myh) 2, Myh4, and Myh7 expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP) muscles of sham and CLP mice at 96 h after surgery as indicated (WT sham: n = 5; WT CLP: n = 9; Nlrp3 KO sham n = 5; Nlrp3 KO: CLP n = 6). mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. (c–f) qRT-PCR analysis of Trim63 (MuRF1) and Fbxo32 (atrogin 1) expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris and tibialis anterior muscle of sham and CLP-operated WT and Nlrp3 KO mice at 96 h after surgery as indicated (WT sham: n = 5; WT CLP: n = 9; Nlrp3 KO sham n = 5; Nlrp3 KO: CLP n = 6). mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns = not significant; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

Discussion

ICUAW is a devastating disease warranting detailed mechanistic investigation [2, 45]. In our study, we found a close relationship between systemic inflammation in sepsis and muscle atrophy. We show that IL-1β signaling is present in myocytes and when activated leads to myocyte atrophy in vitro. Germline deletion of Nlrp3 in mice led to reduced IL-1β serum levels in response to inflammation and less inflammation-induced muscle atrophy in vivo. These data underscore the conclusion that during inflammation, skeletal muscle and myocytes are targeted by IL-1β to undergo atrophy. However, since Nlrp3 is ubiquitously expressed [31, 32], the observed reduction in IL-1β serum levels in response to inflammation was most likely caused by the absence of Nlrp3 in multiple cells, tissues, and organs and not only muscle. Nevertheless, our findings suggest Nlrp3 as target for treatment against inflammation-induced atrophy.

Based on earlier published work, we suggest that muscle contributes to inflammation and acute-phase response. Of note, the acute-phase response protein serum amyloid A1 (SAA1) was shown to be synthesized by and released from muscle of critically ill patients and septic mice [36]. SAA1 induces IL-1β expression [46] and secretion [47] and activates the Nlrp3 inflammasome in immune cells [46]. The Nlrp3 inflammasome is contained and active in C2C12 myocytes [48]. IL-1β induces atrogene expression in myocytes [23]. Together, these data suggest feedback loops between IL-1β, IL6, SAA1, and Nlrp3 during inflammation reinforcing muscle atrophy in critical illness. Here, we show that Il1b and Il6 as well as Nlrp3 expression are increased in muscles of septic mice. We show that the IL-1β signaling pathway is contained and active in myocytes in vitro. Based on these observations, it is possible that Nlrp3 KO mice have less overall inflammation during sepsis when compared to Nlrp3 WT animals and that not only decreased IL-1β levels but also reduced overall inflammation contributed to reduced muscle atrophy in septic Nlrp3 KO mice. However, since we did not perform a comprehensive analysis of inflammation in our mice, we cannot provide a definitive answer to this hypothesis.

We hypothesized that activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome plays a role in inflammation-mediated muscle atrophy via activation of IL-1β. The Nlrp3 inflammasome is activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns [49] and host-derived molecules, such as DNA, which indicates cellular damage and cell death, so-called damage-associated molecular patterns [50]. Nlrp3 inflammasome could therefore contribute to both pathogen-associated immune responses and sterile-inflammation. We found that depletion of Nlrp3 in mice not only increases their survival in sepsis but also inhibits sepsis and inflammation-mediated muscle atrophy. We believe that this phenotype is predominantly caused by the missing conversion of pro-IL-1β to IL-1β. We demonstrate that IL-1β induces atrophy presumably via the IL-1 signaling pathway leading to NF-κB activation and increased MuRF1 and atrogin 1 expression in vitro. This interpretation is in line with published work showing that IL-1β increases atrogene expression in vitro [23]. Likewise, decreased activation of IL-1β in Nlrp3 KO mice during sepsis resulted in decreased Il6 expression, which is a target of IL-1β and mediates atrophy [36, 51]. We hypothesize that blockage of Nlrp3 inhibits sensing of pathogen and host signals, which is followed by inhibition of IL-1β- and IL-6-dependent damage pathways resulting in better survival and reduced muscle atrophy.

IL-6 and SAA1 mRNA and protein expression are increased in muscle of critically ill patients [7, 36]. These factors promote continuous inflammation and acute-phase response that in turn triggers ICUAW. We observed that IL-1β induces Il6 and Nlrp3 expression in cultured myocytes. After 24 h of treatment, expression levels of both genes dropped. In contrast, in septic mice, the muscular expression of Il6 mRNA is still markedly increased after 96 h post CLP, reflecting the situation of critically ill patients. Our data add IL-1β and Nlrp3 as further cytokine network factors, highly expressed in the skeletal muscle during systemic inflammation. The observed differences between cultured myocytes and muscle tissue could be explained by the fact that a functional cytokine network relies on interacting organs rather than cell-to-cell communications within an isolated organ. This interpretation implies that the muscle, although itself an immune organ, requires interaction and feedback from other organs to fully respond to systemic inflammation. Taken together, during systemic inflammation, muscular expression of SAA1, IL-6, Nlrp3, and IL-1β is persistently elevated, which might contribute to atrophy.

An imbalanced muscular protein homeostasis plays a dominant role in muscle failure of critically ill patients [4, 10, 38]. Atrogin 1 and MuRF1 are key “atrogenes” in this process [10, 22, 38, 52]. Our finding that atrogene expression was not increased in Nlrp3 KO indicates that atrogene expression is regulated by Nlrp3-dependent IL-1β activation. Muscle atrophy is accompanied by increased MyHC degradation and decreased MyHC expression [10]. Whereas sepsis led to a decreased Myh2 and Myh7 expression in muscle of WT, this effect was blunted in Nlrp3 KO. Because IL-1β treatment leads to decreased Myh2, Myh4, and Myh7 expression in myocytes, reduced muscular MyHC expression during sepsis might be caused by IL-1β. Our data indicate that Nlrp3-mediated IL-1β activation may affect both major branches of protein homeostasis and therefore regulate MyHC synthesis via mRNA expression as well as UPS-mediated MyHC degradation.

Conclusions

We suggest that Nlrp3-mediated IL-1β activation in sepsis is a major pathogenic mechanism in inflammatory muscle atrophy. Inhibition of IL-1β could be useful to prevent ICUAW in critically ill patients. Since not only sepsis is associated with inflammation-induced muscle failure and increased IL-1β levels other forms of muscle atrophy might also profit from Nlrp3/IL-1β inhibition; for example, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. However, IL-1β is only one of many cytokines that are elevated during the cytokine storm in the acute phase of sepsis. It was shown that IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were below detection limit in patients with septic shock admitted to an ICU [41]. In these patients, continuously high IL-6 serum levels were measured. IL-6 was not only negatively associated with muscular myosin contents, a marker for muscle atrophy, but also provoked atrophy in myocytes in vitro [41]. These data indicate that inhibition of multiple cytokines as well as its correct timing is important to reduce inflammation-induced atrophy. However, unlike during controlled conditions in animal experiments, the precise time point of sepsis onset in patients is often unknown which impedes such treatment decisions for the caring clinician. The key to a targeted therapy of inflammation-induced atrophy in sepsis is, therefore, a better characterization of the disease process, and we think that animal models are helpful in this regard.

Abbreviations

- CLP:

-

Cecal ligation and puncture model of polymicrobial sepsis

- Fbxo32:

-

F-box only protein 32 (mouse gene encoding atrogin 1)

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ICUAW:

-

Intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired weakness

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MCSA:

-

Myocyte cross-sectional area

- MuRF:

-

Muscle really interesting new gene (RING)-finger containing protein

- Myh:

-

Myosin heavy chain

- Nlrp3:

-

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD), leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain containing 3 (mouse gene encoding Nalp3)

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- Trim63:

-

Tripartite motif containing 63 (mouse gene encoding MuRF1)

References

Bierbrauer J, Koch S, Olbricht C, Hamati J, Lodka D, Schneider J, Luther-Schröder A, Kleber C, Faust K, Wiesener S, Spies CD, Spranger J, Spuler S, Fielitz J, Weber-Carstens S (2012) Early type II fiber atrophy in intensive care unit patients with nonexcitable muscle membrane. Crit Care Med 40:647–650

Bolton CF (1993) Neuromuscular complications of sepsis. Intensive Care Med 19(Suppl 2):S58–S63

Lefaucheur JP, Nordine T, Rodriguez P, Brochard L (2006) Origin of ICU acquired paresis determined by direct muscle stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77:500–506

Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, Hopkinson NS, Phadke R, Padhke R, Dew T, Sidhu PS, Velloso C, Seymour J, Agley CC, Selby A, Limb M, Edwards LM, Smith K, Rowlerson A, Rennie MJ, Moxham J, Harridge SDR, Hart N, Montgomery HE (2013) Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA 310:1591–1600

De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur J-P, Authier F-J, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, Cerf C, Renaud E, Mesrati F, Carlet J, Raphaël J-C, Outin H, Bastuji-Garin S, Groupe de Réflexion et d’Etude des Neuromyopathies en R (2002) Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA 288:2859–2867

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Kudlow P, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Cheung AM, Canadian Critical Care Trials G (2011) Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 364:1293–1304

Weber-Carstens S, Deja M, Koch S, Spranger J, Bubser F, Wernecke KD, Spies CD, Spuler S, Keh D (2010) Risk factors in critical illness myopathy during the early course of critical illness: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 14:R119

Winkelman C (2010) The role of inflammation in ICU-acquired weakness. Crit Care 14:186

Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, Friscia ME, Budak MT, Rothenberg P, Zhu J, Sachdeva R, Sonnad S, Kaiser LR, Rubinstein NA, Powers SK, Shrager JB (2008) Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med 358:1327–1335

Wollersheim T, Woehlecke J, Krebs M, Hamati J, Lodka D, Luther-Schroeder A, Langhans C, Haas K, Radtke T, Kleber C, Spies C, Labeit S, Schuelke M, Spuler S, Spranger J, Weber-Carstens S, Fielitz J (2014) Dynamics of myosin degradation in intensive care unit-acquired weakness during severe critical illness. Intensive Care Med 40:528–538

Klaude M, Mori M, Tjäder I, Gustafsson T, Wernerman J, Rooyackers O (2012) Protein metabolism and gene expression in skeletal muscle of critically ill patients with sepsis. Clin Sci (Lond) 122:133–142

Constantin D, McCullough J, Mahajan RP, Greenhaff PL (2011) Novel events in the molecular regulation of muscle mass in critically ill patients. J Physiol Lond 589:3883–3895

Helliwell TR, Wilkinson A, Griffiths RD, McClelland P, Palmer TE, Bone JM (1998) Muscle fibre atrophy in critically ill patients is associated with the loss of myosin filaments and the presence of lysosomal enzymes and ubiquitin. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 24:507–517

Dinarello CA (2005) Interleukin-1beta. Crit Care Med 33:S460–S462

Pruitt JH, Copeland EM, Moldawer LL (1995) Interleukin-1 and interleukin-1 antagonism in sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and septic shock. Shock 3:235–251

Sullivan JS, Kilpatrick L, Costarino AT, Lee SC, Harris MC (1992) Correlation of plasma cytokine elevations with mortality rate in children with sepsis. J Pediatr 120:510–515

Cannon JG, Tompkins RG, Gelfand JA, Michie HR, Stanford GG, van der Meer JW, Endres S, Lonnemann G, Corsetti J, Chernow B (1990) Circulating interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor in septic shock and experimental endotoxin fever. J Infect Dis 161:79–84

Jean-Baptiste E (2007) Cellular mechanisms in sepsis. J Intensive Care Med 22:63–72

van Deuren M (1994) Kinetics of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors, interleukin 1-beta and its receptor antagonist during serious infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 13(Suppl 1):S12–S16

Salkowski CA, Detore G, Franks A, Falk MC, Vogel SN (1998) Pulmonary and hepatic gene expression following cecal ligation and puncture: monophosphoryl lipid A prophylaxis attenuates sepsis-induced cytokine and chemokine expression and neutrophil infiltration. Infect Immun 66:3569–3578

Llovera M, Carbó N, López-Soriano JN, Garcı́a-Martı́nez C, Busquets S, Alvarez B, Agell N, Costelli P, López-Soriano FJ, Celada A, Argilés JM (1998) Different cytokines modulate ubiquitin gene expression in rat skeletal muscle. Cancer Lett 133:83–87

Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ (2001) Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294:1704–1708

Li W, Moylan JS, Chambers MA, Smith J, Reid MB (2009) Interleukin-1 stimulates catabolism in C2C12 myotubes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297:C706–C714

Afonina Inna S, Müller C, Martin Seamus J, Beyaert R (2015) Proteolytic processing of interleukin-1 family cytokines: variations on a common theme. Immunity 42:991–1004

Cerretti DP, Kozlosky CJ, Mosley B, Nelson N, Van Ness K, Greenstreet TA, March CJ, Kronheim SR, Druck T, Cannizzaro LA (1992) Molecular cloning of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science 256:97–100

Dinarello CA (2009) Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 27:519–550

Dinarello CA, Cannon JG, Wolff SM, Bernheim HA, Beutler B, Cerami A, Figari IS, Palladino MA, O’Connor JV (1986) Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) is an endogenous pyrogen and induces production of interleukin 1. J Exp Med 163:1433–1450

Dinarello CA, Ikejima T, Warner SJ, Orencole SF, Lonnemann G, Cannon JG, Libby P (1987) Interleukin 1 induces interleukin 1. I. Induction of circulating interleukin 1 in rabbits in vivo and in human mononuclear cells in vitro. J Immunol 139:1902–1910

Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G, Tschopp J (2011) The inflammasome: an integrated view. Immunol Rev 243:136–151

Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM (2012) Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28:137–161

Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE (2003) The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 348:138–150

Schroder K, Tschopp J (2010) The inflammasomes. Cell 140:821–832

Brigelius-Flohé R, Banning A, Kny M, Böl G-F (2004) Redox events in interleukin-1 signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys 423:66–73

Rawat R, Cohen TV, Ampong B, Francia D, Henriques-Pons A, Hoffman EP, Nagaraju K (2010) Inflammasome up-regulation and activation in dysferlin-deficient skeletal muscle. Am J Pathol 176:2891–2900

Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J (2006) Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440:237–241

Langhans C, Weber-Carstens S, Schmidt F, Hamati J, Kny M, Zhu X, Wollersheim T, Koch S, Krebs M, Schulz H, Lodka D, Saar K, Labeit S, Spies C, Hubner N, Spranger J, Spuler S, Boschmann M, Dittmar G, Butler-Browne G, Mouly V, Fielitz J (2014) Inflammation-induced acute phase response in skeletal muscle and critical illness myopathy. PLoS ONE 9:e92048

Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, Ward PA (2009) Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc 4:31–36

Schmidt F, Kny M, Zhu X, Wollersheim T, Persicke K, Langhans C, Lodka D, Kleber C, Weber-Carstens S, Fielitz J (2014) The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM62 and inflammation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Crit Care 18:545

Yaffe D, Saxel O (1977) Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 270:725–727

Blau HM, Pavlath GK, Hardeman EC, Chiu CP, Silberstein L, Webster SG, Miller SC, Webster C (1985) Plasticity of the differentiated state. Science 230:758–766

van Hees HW, Schellekens WJ, Linkels M, Leenders F, Zoll J, Donders R, Dekhuijzen PN, van der Hoeven JG, Heunks LM (2011) Plasma from septic shock patients induces loss of muscle protein. Crit Care 15:R233

Passey SL, Bozinovski S, Vlahos R, Anderson GP, Hansen MJ (2016) Serum amyloid A induces Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inflammatory cytokine expression and atrophy in C2C12 skeletal muscle myotubes. PLoS ONE 11:e0146882

Hoene M, Runge H, Haring HU, Schleicher ED, Weigert C (2013) Interleukin-6 promotes myogenic differentiation of mouse skeletal muscle cells: role of the STAT3 pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304:C128–C136

Zhu X, Kny M, Schmidt F, Hahn A, Wollersheim T, Kleber C, Weber-Carstens S, Fielitz J, (2016) Secreted frizzled-related protein 2 and inflammation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Crit Care Med. [Epub ahead of print]

Callahan LA, Supinski GS (2009) Sepsis-induced myopathy. Crit Care Med 37:S354–S367

Niemi K, Teirilä L, Lappalainen J, Rajamäki K, Baumann MH, Öörni K, Wolff H, Kovanen PT, Matikainen S, Eklund KK (2011) Serum amyloid A activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via P2X7 receptor and a cathepsin B-sensitive pathway. J Immunol 186:6119–6128

Yu N, Liu S, Yi X, Zhang S, Ding Y (2015) Serum amyloid A induces interleukin-1β secretion from keratinocytes via the NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 inflammasome. Clin Exp Immunol 179:344–353

Cho K-A, Kang PB (2015) PLIN2 inhibits insulin-induced glucose uptake in myoblasts through the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Int J Mol Med 36:839–844

Kanneganti T-D, Ozören N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park J-H, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Akira S, Núñez G (2006) Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature 440:233–236

Jin C, Flavell RA (2010) Molecular mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Clin Immunol 30:628–631

LeMay LG, Otterness IG, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ (1990) In vivo evidence that the rise in plasma IL 6 following injection of a fever-inducing dose of LPS is mediated by IL 1 beta. Cytokine 2:199–204

Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, Gomes M, Baracos V, Bailey J, Price SR, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL (2004) Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J 18:39–51

Acknowledgements

We thank Aubry Tardivel and Nicolas Fasel of the University of Lausanne for providing Nlrp3 KO mice. We thank Mihail Todiras for the helpful discussions, logistical support, and hospitality.

Funding

JF received grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FI 965/4-1, FI 965/5-1, FI 965/5-2). FCL and JF received funding from the Experimental and Clinical Research Center and the Berlin Institute of Health. FR and JF received funding from Ernst und Berta Grimmke Stiftung.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

NH, MK, FR, KB, SS, HS, FCL, and JF designed and analyzed the experiments, discussed the data, and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, were approved by the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin, Germany (G207/13, G129/12), and followed the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) and the current version of German Law on the Protection of Animals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Materials and Methods. (DOCX 78 kb)

Additional file 2:

Polymicrobial sepsis increases Nlrp3, Il1b, and Il6 expression in the muscle. Twelve-week-old male C57B16/J mice were subjected to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) or sham surgery (sham), as indicated. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of Nlrp3, IL-1β, and Il6 expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP) and (B) tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of sham (n = 5) and CLP (n = 5) mice 4 days after surgery. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (EPS 1161 kb)

Additional file 3:

Body and organ weights of Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were indistinguishable at baseline. Weights of body (A), liver and spleen (B), and muscle (C); gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP), tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (Sol) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL)); Nlrp3 KO (n = 6); WT (n = 6). All weights were normalized to tibia length and expressed as percent wise change compared to WT. Animals were 12–16-week-old males. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ns = not significant. (EPS 1175 kb)

Additional file 4:

Septic Nlrp3 KO mice show no decrease in liver weight but an increase in spleen weight. Twelve- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery. Weights were determined at 96 h after surgery. (A) Liver and (B) spleen weight. (C, D) Weights of the skeletal muscles (C) soleus (Sol) and (D) extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (WT sham (n = 13), WT CLP (n = 12), Nlrp3 KO sham (n = 8), Nlrp3 KO CLP (n = 16)). All weights were normalized to tibia length and expressed as percent wise change compared to the respective sham group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ns = not significant. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (EPS 1427 kb)

Additional file 5:

Baseline muscular Il6 and Il1b expression in Nlrp3 KO and WT mice. qRT-PCR analysis of (A) Il6 and (B) IL1b expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles as indicated. Nlrp3 KO (n = 6) and WT (n = 6). mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ns = not significant. (EPS 1144 kb)

Additional file 6:

Inflammation-induced increase in muscular Il6 and Il1b expression as well as serum IL-1β levels are blunted in Nlrp3 KO mice. Twelve- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery, as indicated. At 96 h after surgery, analyses were performed. (A–D) qRT-PCR analysis of (A, B) Il1b and (C, D) Nlrp3 expression in gastrocnemius/plantaris (GP) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of WT sham (n = 5), WT CLP (n = 9), Nlrp3 KO sham (n = 5), and Nlrp3 KO CLP (n = 6) mice. mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. (E, F) Serum IL-1β was determined in WT and Nlrp3 KO mice using the Abcam kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. (E) Serum IL-1β concentration at baseline. (F) Serum IL-1β concentration in Sham and CLP mice. WT-sham (n = 15), WT-CLP (n = 12), Nlrp3 KO-sham (n = 14), Nlrp3 KO-CLP (n = 14). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. n.d. = not detected. (EPS 1443 kb)

Additional file 7:

Inflammation-induced decrease of myosin heavy chain gene expression is blunted in Nlrp3 KO mice. Twelve- to 16-week-old male Nlrp3 KO and WT mice were subjected to CLP or sham surgery. qRT-PCR analysis of myosin heavy chain (Myh) 2, Myh4, and Myh7 expression in tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of sham (n = 5) and CLP (n = 5) mice at 96 h after surgery as indicated (WT sham: n = 5; WT CLP: n = 9; Nlrp3 KO sham n = 5; Nlrp3 KO: CLP n = 6). mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant; **p ≤ 0.01. (EPS 1369 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, N., Kny, M., Riediger, F. et al. Deletion of Nlrp3 protects from inflammation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. ICMx 5, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-016-0115-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-016-0115-0