Abstract

Purpose

To quantify the influence of the femoral tunnel exit (FTE) on the graft bending angle (GBA) and GBA-excursion throughout a full range of motion (ROM) in single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

Methods

Three-dimensional (3D) surface models of five healthy knees were generated from a weight-bearing CT obtained throughout a full ROM (0, 30, 60, 90, 120°) and femoral and tibial ACL insertions were computed. The FTE was simulated for 16 predefined positions, referenced to the Blumensaat's line, for each patient throughout a full ROM (0, 30, 60, 90, 120°) resulting in a total of 400 simulations. 3D GBA was calculated between the 3D directional vector of the ACL and the femoral tunnel, while the intra-articular ACL insertions remained unchanged. For each simulation the 3D GBA, GBA-excursion, tunnel length and posterior tunnel blow-out were analysed.

Results

Overall, mean GBA decreased with increasing knee flexion for each FTE (p < 0.001). A more distal location of the FTE along the Blumensaat's line resulted in an increase of GBA and GBA-excursion of 8.5 ± 0.6° and 17.6 ± 1.1° /cm respectively (p < 0.001), while a more anterior location resulted in a change of GBA and GBA-excursion of -2.3 ± 0.6° /cm (+ 0.6 ± 0.4°/ cm from 0–60° flexion) and 9.8 ± 1.1 /cm respectively (p < 0.001).

Mean tunnel length was 38.5 ± 5.2 mm (range 29.6–50.5). Posterior tunnel blow-out did not occur for any FTE.

Conclusion

Aiming for a more proximal and posterior FTE, with respect to Blumensaat’s line, reliably reduces GBA and GBA-excursion, while preserving adequate tunnel length. This might aid to reduce excessive graft stress at the femoral tunnel aperture, decrease femoral tunnel widening and promote graft-healing.

Level of Evidence

IV

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is widely used to restore knee function and successful graft incorporation is key to restore knee stability and prevent graft failure. Numerous factors have been shown to influence graft failure after ACL reconstruction, as biological [21], laxity [35], graft choice [11], fixation technique [10], and anatomical tunnel positioning [25].

Previous studies have recently supported the role of the graft bending angle (GBA) in graft incorporation as more acute GBAs might lead to excessive stress between the graft and the anterior femoral tunnel aperture [1, 7]. From a biomechanical point of view, not only the GBA but also the GBA-excursion throughout the full knee range of motion (ROM) is likely to play an important role in graft stress and friction at the femoral tunnel inlet. This effect potentially impairs essential bone to tendon healing and is associated with increased femoral tunnel widening [17] and possibly explains the higher graft failure rate at the location of the femoral tunnel aperture [20]. Decreased graft maturation in the presence of an acute GBA has been confirmed with the signal/noise quotient (SNQ) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially in the early phase of graft incorporation [13, 16]. Moreover, GBA is known to be accentuated during motion and weight bearing activities and increasing stress on the proximal bone-graft interface [31]. Another factor to be considered regarding the femoral tunnel is its length [32], which contributes to initial fixation strength [6, 34].

The role of the femoral tunnel exit (FTE) has only been studied scarcely. For example, previous studies reported a more acute GBA with a more anterior FTE with the use of flexible drills or depending on the technique (outside in vs. transportal vs. transtibial) [14, 30]. However, no systematic analysis of the FTE and its relationship with GBA, GBA-excursion and femoral tunnel length throughout a full range of motion under weight-bearing conditions exists to our knowledge. We hypothesized that the location of the FTE significantly influences the GBA. Therefore, the aim of the study was to quantify the influence of the FTE on GBA, GBA-excursion and femoral tunnel length in single-bundle ACL reconstruction under weight-bearing conditions.

Methods

After local review board approval, weight-bearing computer-tomography (CT) scans of five male volunteers with a mean age of 36 years (range 29 to 42 years), obtained for a previous study [5] were used for the 3D simulation. No participant had previous knee injury or surgery. High-resolution CT images of the left knee in increasing knee flexion (0, 30, 60, and 120°) were acquired using an open extremity CT scanner (Verity, Planmed, Norway ©; slice thickness 0.4 mm). All scanned knees were included for analysis.

3D triangular surface models were computed with manual threshold segmentation and region growing using MIMICS software (MIMICS, Materialize, Belgium). Afterwards, the models were imported into the in house developed planning software CASPA (Balgrist, Zurich, Switzerland). The femur remained stationary at 0° flexion as a reference and the tibia motion was defined relative to the femur during flexion. The femur models of each subject were superimposed using an iterative closest point surface registration algorithm [3] and five increasing knee flexion angles (0, 30, 60, 90, 120°) were interpolated to minimize the effect of different degrees of flexion among individuals from data acquisition.

Definition of intra-articular ACL insertions

The intra-articular tibial and femoral ACL insertion points were defined based on weighted means of anatomic insertion sites as described by Parkar et al. [24] who reported the tibial insertions according to Stäubli et al. [29] and the femoral insertions according to Bernard et al. [2].

The tibial ACL insertion points were defined as follows (Fig. 1):

-

1.

A plane was fitted to the tibial joint plane by defining three surface points on the medial and lateral plateau in a standardized way (A).

-

2.

Anterior and posterior border planes (orange) were defined to be tangent to the most anterior and posterior margin of the tibial plateau with the normal vector being the cross product of the normal vector of the tibia joint plane and the tangent vector to the posterior condyles. Analogue a medial and lateral border plane (red) were defined being perpendicular to the anterior/posterior boarder plane and the tibial joint plane (B).

-

3.

The anterior border was shifted 42.3% of the total antero-posterior distance posteriorly and the medial border plane was shifted to 50% of the mediolateral distance to the middle (violet intersection). The resulting intersection with the tibial plateau defined the ACL tibial insertion (pink) (C).

Tibial ACL insertion. Definition of 3D tibial ACL insertion based on Stäubli et al. [29] and described in the text

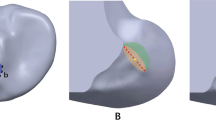

The femoral ACL insertion was simulated as follows (Fig. 2):

-

1.

The vector between the most prominent points on the posterior medial and lateral femur condyle was defined as the posterior condyle line (A).

-

2.

A perpendicular sagittal cut plane (violet) to the posterior condyle line was created through the center of the posterior condyle line to visualize the Blumensaat’s line (B, C).

-

3.

High and low border planes (green) were defined to be tangent to the Blumensaat’s line and posterior margin of the femoral condyle with the normal vector being the cross product of the normal vector of the sagittal cut plane and the tangent vector to the Blumensaat’s line. Analogue a deep and shallow border plane (pink) were defined being perpendicular to the anterior/posterior boarder plane and the sagittal cut plane (B).

-

4.

The deep plane was shifted 28.6% in direction shallow and the high plane was shifted 34.5% in direction low (blue intersection) (E). The resulting intersection with the femur defined the femoral ACL insertion site (F).

Femoral ACL insertion. Definition of 3D femoral ACL insertion based on Bernard et al. [2] and described in the text

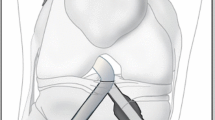

The FTE points were defined as follows (Fig. 3):

-

1.

Steps A-C are equal to Fig. 2.

-

2.

Blumensaat's plane was duplicated and rotated around the x-axis (red arrow) of its own coordinate system until fitting to the inclined lateral cortical surface and referred to as the lateral cortical plane (green) (D, E).

-

3.

Additionally, to define the most posterior aspect of the FTE a plane tangent to the posterior cortical surface was created and referred to as the posterior cortical plane (orange). First, the most proximal and posterior point was defined without violating the intersection of the Blumensaat’s plane (violet) and the posterior cortical plane (orange) to avoid tunnel blow-out. Subsequently, 16 spheres (8 mm diameter) with a distance of one cm between centers were created with their centers intersecting the lateral cortical plane. Referenced to the Blumensaat's plane, four points forming a row and the direction to the posterior cortical plane is subsequently referred to as proximal and the opposite distal. Four points forming a line and the points closer to the Blumensaat's plane are referred to as posterior and the opposite anterior (F).

Graft bending angle (GBA), GBA-excursion and tunnel length

While the intra-articular insertion was left unchanged, the FTE was simulated on the lateral cortical surface of the femur at 16 predefined points (Fig. 3) for each knee flexion position (0, 30, 60, 90, 120°) resulting in 400 simulations. The femoral tunnel diameter was set to 8 mm, representing an average tunnel size.

The 3D GBA (α) was calculated using the scalar product of the 3D directional vector of the ACL (\(\overrightarrow{a}\)) and the 3D directional vector of the simulated femoral tunnel (\(\overrightarrow{b}\)). The ACL vector was defined from the tibial to the femoral insertion point and the femoral tunnel vector between the femoral insertion site and the simulated FTE (Fig. 4):

The GBA-excursion was defined as follows: ΔGBA = GBA (0° flexion) – GBA (120° flexion).

Additionally, for each simulation the tunnel length and posterior blow-out were evaluated. Tunnel length was defined from the center of the femoral ACL insertion to the center of the FTE and corrected for the radius of the femoral exit sphere (4 mm), as the spheres were projected to the surface of the femur corticalis. To correct for absolute body height, tunnel length was adjusted to the distance from the medial to the lateral epicondyle as follows: Tunnel length corr = Absolute tunnel length (mm) * epicondylar distance (mm)/100. Posterior blow out was defined if the femoral tunnel breached the posterior femur corticalis.

Statistics

Normal distribution of the data was tested with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and histograms.

One-way ANOVA was performed to analyse differences of GBA among flexion grades (0, 30, 60, 90, 120°). Multiple post-hoc testing was Bonferroni corrected.

The effect of distalisation, anteriorisation of the FTE and knee flexion on GBA, GBA-excursion and tunnel length were analysed using a linear regression model. Linearity and absent collinearity of the variables and respective errors were confirmed using scatterplots and histograms. To assess a potential change of effect size in a functional ROM close to extension (0, 30, 60°) solely, the linear regression model was repeated for this subgroup in an analogue manner. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s D (f2) and graded as weak: < 0.02, medium: 0.15–0.35 and strong effect > 0.35 [9].

Results

Overall, the mean GBA was highest in 0° flexion and lowest in 120° (p < 0.001); (90° vs. 120° p = 0.002, remaining differences between flexion grades: p < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Mean graft bending angle (GBA) for all subjects and FTE among flexion grades. GBA: Graft bending angle. SD: Standard deviation. Boxplots depicts mean (line), 1st and 3rd quartile (box), minimum and maximum (whisker). Significant differences between groups after Bonferroni correction marked with * (90° vs. 120° p = 0.002), remaining: p < 0.001; ANOVA). Red dotted line: FTE with the greatest mean GBA-excursion; ΔGBA = 102.1 ± 6.3° (most distal-anterior FTE). Green dotted line: FTE with the smallest mean GBA-excursion; ΔGBA = 21.7 ± 6.9° (most proximal-posterior FTE)

The linear regression model was highly significant; F(3,399) = 638,22, p < 0.001, n = 400 and 82.9% of variance is explained by the FTE distalisation, anteriorisation and knee flexion, which corresponds to a strong effect (f2 = 4.85). A more distal location of the FTE along the Blumensaat’s line resulted in an increase of the GBA by 8.5 ± 0.6° /cm (p < 0.001). A more anterior FTE resulted in a decrease of GBA by -2.3 ± 0.6°/ cm (p < 0.001). Knee flexion led to a decrease of GBA by -18.6 ± 0.5° /30° of knee flexion (p < 0.001).

The repeated linear model close to extension (0–60°) showed an increase in effect size; F(3,239) = 777.32, p < 0.001, n = 240. 90.7% of variance is explained by the previous described three factors, which corresponds to a strong effect (f2 = 9.75). A more distal location of the FTE along the Blumensaat’s line resulted in an increase of the GBA by 13.0 ± 0.4° /cm (p < 0.001). A more anterior FTE resulted in an increase of GBA by 0.6 ± 0.4°/cm (p < 0.001). Knee flexion led to a decrease of GBA by -22.3 ± 0.6° /30° of knee flexion (p < 0.001).

Both, a more distal and a more anterior location of the FTE along the Blumensaat’s line resulted in an increase of GBA-excursion by 17.6 ± 1.1° /cm (p < 0.001) and 9.8 ± 1.1 /cm (p < 0.001), respectively; (F(2,79) = 160.70, p < 0.001, n = 80; f2 = 4.05).

Mean tunnel length was 38.5 ± 5.2 mm (range 29.6–50.5). Both, a more distal and anterior location of the FTE along the Blumensaat’s line resulted in an increase of tunnel length corr by 1.1 ± 0.3 /cm (p < 0.001) and 3.6 ± 0.3 /cm (p < 0.001), respectively; F(2,79) = 110.33, p < 0.001, n = 80; (f2 = 2.77). Posterior tunnel blow-out did not occur for any FTE.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that a more proximal and posterior FTE, with respect to Blumensaat’s line, reduces GBA and GBA-excursion while preserving adequate tunnel length. Overall, GBA is reduced with increasing knee flexion.

The distalisation of the FTE showed the highest impact on GBA, while the anteriorisation had a considerably minor impact on GBA. Both, distalisation and anteriorisation, showed strict linearity until 60° of knee flexion but the effect of anteriorisation on GBA inverted in 90 and 120° and distalisation inverted in 120° of knee flexion (Fig. 6). This is also highlighted by the substantial increase of the effect size of the linear model for the subgroup close to extension (0–60°). However, mean GBA trebles in extension (0°) compared to flexion (90,120°) (Fig. 5) and despite the inverted relationship of the GBA in flexion compared to extension, the GBA for every FTE decreased throughout the full ROM. Therefore, these results strongly support to aim for the lowest GBA and GBA-excursion in full extension, which corresponds to the most posterior and proximal FTE. Additionally, most weight-bearing activities and rehabilitation exercises take place near full knee extension, which supports its clinical importance [4]. Looking at the GBA-excursion reveals the analogue behaviour as described for the GBA and underlines the relevance of a proximal and posterior FTE.

Mean GBA among flexion grades and femoral exit points. GBA: graft bending angle. 3D bar chart depicts GBA (y-axis) for each flexion° and for each FTE. All bar charts are oriented as in the model on the top left, listing the FTE with respect to the Blumensaat’s line (x-axis (rows; proximal to distal) and z-axis (lines; posterior to anterior)

Finally, an adequate length for all femoral tunnels was preserved for all simulations if FTE is placed above the Blumensaat’s line and tunnel blow-out did not occur if the described landmarks (Blumensaat’s line and posterior cortical tangent) were respected [28].

Looking at the most proximal posterior FTE vs. most distal anterior demonstrates a halving of GBA and a five-fold decrease of GBA-excursion but the clinical relevance of this finding remains debatable. The role of GBA has been studied previously in regard to tunnel widening [33] and graft maturation [7, 17, 27]. Moreover, in posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) reconstruction a sharp GBA has been shown to not only attenuate the graft due to repetitive friction between the graft and tunnel inlet but even leading to graft displacement and residual laxity [18]. To decrease friction and graft strain, chamfering the intra-articular femoral tunnel inlet poses a surgical option. Graft maturation and bone tendon healing at femoral tunnel aperture are crucial issues that have not been resolved in ACL reconstruction so far and potentially delay rehabilitation, return to sports and ultimately may increase the risk of graft failure [8, 22].

The clinical applicability of our findings especially aids surgeons who perform an outside-in technique as they can define the FTE (respectively starting point) arbitrarily [19, 23], or if intraoperative fluoroscopy is used as in all-epiphyseal ACL reconstruction techniques in a paediatric population, for example [15]. However, aiming for the proposed optimal FTE position (posterior, proximal) in all-epiphyseal techniques is strictly limited by the epiphyseal line that only allows for a more distal FTE and a higher GBA respectively. Another important aspect that will allow the guidance of the FTE is the potential for navigated tunnel placement, for example, using augmented-reality [12, 26].

A limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size of five legs that did not allow the analysis of intra-subject morphometric anatomic variants. However, 16 FTE have been simulated in one-centimeter steps throughout the full ROM, resulting in 400 simulations. We are aware of the inverted relationship between FTE and GBA and GBA-excursion during deep knee flexion, which has been addressed by a subgroup analysis near extension (0–60°) and resulted in a very strong effect size of the model. The impact of in vivo kinematics on GBA in various activities can not be drawn from this study design. However, the use of a weight-bearing model revealed consistent outcomes compared to previous in-vivo results [31]. The impact of GBA on clinical outcome and the intraoperative applicability to guide the FTE remain subjects of further research.

Conclusion

Aiming for a more proximal and posterior FTE, with respect to Blumensaat’s line, reliably reduces GBA and GBA-excursion, while preserving adequate tunnel length. This might aid to reduce excessive graft stress at the femoral tunnel aperture, femoral tunnel widening and enhance graft-healing.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- CT:

-

Computer-tomography

- FTE:

-

Femoral tunnel exit

- GBA:

-

Graft bending angle

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- SNQ:

-

Signal/noise quotient

References

Ahn JH, Jeong HJ, Lee YS, Park JH, Lee JH, Ko TS (2016) Graft bending angle is correlated with femoral intraosseous graft signal intensity in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the outside-in technique. Knee 23:666–673

Bernard M, Hertel P (1996) Intraoperative and postoperative insertion control of anterior cruciate ligament-plasty. A radiologic measuring method (quadrant method). Unfallchirurg 99:332–340

Besl PJ, McKay ND (1992) Method for registration of 3-D shapes. Sensor fusion IV control paradigms and data structures International Society for Optics and Photonics. pp 586–606

Biggs A, Jenkins WL, Urch SE, Shelbourne KD (2009) Rehabilitation for patients following ACL reconstruction: a knee symmetry model. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 4:2–12

Blatter SC, Fürnstahl P, Hirschmann A, Graf M, Fucentese SF (2016) Femoral insertion site in medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Knee 23:456–459

Cavaignac E, Marot V, Faruch M, Reina N, Murgier J, Accadbled F et al (2017) Hamstring graft incorporation according to the length of the graft inside tunnels. Am J Sports Med 46:348–356

Chen L, Wu Y, Lin G, Wei P, Ye Z, Wang Y et al (2018) Graft bending angle affects allograft tendon maturity early after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:3048–3054

Claes S, Verdonk P, Forsyth R, Bellemans J (2011) The “ligamentization” process in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: what happens to the human graft? A systematic review of the literature. Am J Sports Med 39:2476–2483

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic, New York

Colombet P, Graveleau N, Jambou S (2016) Incorporation of hamstring grafts within the tibial tunnel after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: magnetic resonance imaging of suspensory fixation versus interference screws. Am J Sports Med 44:2838–2845

Gabler CM, Jacobs CA, Howard JS, Mattacola CG, Johnson DL (2015) Comparison of graft failure rate between autografts placed via an anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction technique: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Am J Sports Med 44:1069–1079

Guo N, Yang B, Ji X, Wang Y, Hu L, Wang T (2019) Intensity-based 2D-3D registration for an ACL reconstruction navigation system. Int J Med Robot 15:e2008

Hofbauer M, Soldati F, Szomolanyi P, Trattnig S, Bartolucci F, Fu F et al (2019) Hamstring tendon autografts do not show complete graft maturity 6 months postoperatively after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:130–136

Kim JG, Wang JH, Lim HC, Ahn JH (2012) Femoral graft bending angle and femoral tunnel geometry of transportal and outside-in techniques in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an in vivo 3-dimensional computed tomography analysis. Arthroscopy 28:1682–1694

Lawrence JTR, Bowers AL, Belding J, Cody SR, Ganley TJ (2010) All-epiphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in skeletally immature patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:1971–1977

Li H, Chen S, Tao H, Li H, Chen S (2014) Correlation analysis of potential factors influencing graft maturity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med 2:2325967114553552

Li H, Liu S, Sun Y, Li H, Chen S, Chen J (2019) Influence of graft bending angle on graft maturation, the femoral tunnel, and functional outcomes by 12 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med 7:2325967119882663

Li Y, Zhang J, Song G, Li X, Feng H (2016) The mechanism of “killer turn” causing residual laxity after transtibial posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol 3:13–18

Lubowitz JH, Akhavan S, Waterman BR, Aalami-Harandi A, Konicek J (2013) Technique for creating the anterior cruciate ligament femoral socket: optimizing femoral footprint anatomic restoration using outside-in drilling. Arthroscopy 29:522–528

Magnussen RA, Taylor DC, Toth AP, Garrett WE (2012) ACL graft failure location differs between allografts and autografts. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 4:1–6

Menetrey J, Duthon VB, Surgery TLK, Sports (2008) “Biological failure” of the anterior cruciate ligament graft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16:224–231

Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, Fink C, Diermeier T, Rothrauff BB, Svantesson E et al (2020) Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:2403–2414

Nakayama H, Yamaguchi M, Yoshiya S (2014) Comparison of transportal inside-out and outside-in femoral drilling techniques in anatomic ACL reconstruction. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol 1:26–30

Parkar AP, Adriaensen MEAPM, Vindfeld S, Solheim E (2016) The Anatomic centers of the femoral and tibial insertions of the anterior cruciate ligament: a systematic review of imaging and cadaveric studies reporting normal center locations. Am J Sports Med 45:2180–2188

Pinczewski LA, Salmon LJ, Jackson WFM, von Bormann RBP, Haslam PG, Tashiro S (2008) Radiological landmarks for placement of the tunnels in single-bundle reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90:172–179

Raposo C, Barreto JP, Sousa C, Ribeiro L, Melo R, Oliveira JP et al (2019) Video-based computer navigation in knee arthroscopy for patient-specific ACL reconstruction. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 14:1529–1539

Saito M, Nakajima A, Sonobe M, Takahashi H, Akatsu Y, Inaoka T et al (2019) Superior graft maturation after anatomical double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the transtibial drilling technique compared to the transportal technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:2468–2477

Shin YS, Ro KH, Jeon JH, Lee DH (2014) Graft-bending angle and femoral tunnel length after single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Bone Joint J 96-B:743–751

Stäubli HU, Rauschning W (1994) Tibial attachment area of the anterior cruciate ligament in the extended knee position. Anatomy and cryosections in vitro complemented by magnetic resonance arthrography in vivo. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2:138–146

Tashiro Y, Irarrázaval S, Osaki K, Iwamoto Y, Fu FH (2017) Comparison of graft bending angle during knee motion after outside-in, trans-portal and trans-tibial anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:129–137

Tashiro Y, Sundaram V, Thorhauer E, Gale T, Anderst W, Irrgang JJ et al (2017) In vivo analysis of dynamic graft bending angle in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees during downward running and level walking: comparison of flexible and rigid drills for transportal technique. Arthroscopy 33:1393–1402

Wang JH, Kim JG, Lee DK, Lim HC, Ahn JH (2012) Comparison of femoral graft bending angle and tunnel length between transtibial technique and transportal technique in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:1584–1593

Yanagisawa S, Kimura M, Hagiwara K, Ogoshi A, Yoneyama T, Omae H et al (2020) A steep coronal graft bending angle is associated with bone tunnel enlargement of the posterolateral bundle after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Surg 28:2309499019888811

Yang D-L, Cheon S-H, Oh C-W, Kyung H-S (2014) A comparison of the fixation strengths provided by different intraosseous tendon lengths during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a biomechanical study in a porcine tibial model. Clin Orthop Surg 6:173–179

Ziegler CG, DePhillipo NN, Kennedy MI, Dekker TJ, Dornan GJ, LaPrade RF (2021) Beighton score, tibial slope, tibial subluxation, quadriceps circumference difference, and family history are risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament graft failure: a retrospective comparison of primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Arthroscopy 37:195–205

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding has been received for the conductance of this study. Sandro Fucentese is a consultant for Medacta SA (Switzerland).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH conceived the design of the study, performed statistics and wrote the manuscript. SM performed data acquisition and helped drafting the manuscript. LV and PF participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. SF participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and ethics protocol was approved by the Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich (BASEC-Nr. 2013–0374).

Competing interests

No conflicts of interests are present.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hodel, S., Mania, S., Vlachopoulos, L. et al. Influence of femoral tunnel exit on the 3D graft bending angle in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J EXP ORTOP 8, 44 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-021-00364-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-021-00364-9