Abstract

Vertical magnetic transfer functions (tippers) estimated at island observatories can constrain the one-dimensional (1-D) conductivity distribution of the oceanic lithosphere and upper mantle. This is feasible due to the bathymetry-dependent ocean induction effect (OIE), which originates from lateral conductivity contrasts between ocean and land and leads to non-zero tippers even for 1-D conductivity distributions below the ocean. Proper analysis of island tippers requires accurate three-dimensional (3-D) modeling of the OIE, for which so far was performed assuming constant sea water electric conductivity with depth. In this study, we explore—using rigorous 3-D electromagnetic modeling—to what extent realistic, depth-dependent, oceanic conductivity affects island tippers. The modeling is performed for 11 island observatories around the world in the period range \(10^{-1}\) to \(10^{4}\) s. We also investigate the effect of seasonal variations of the oceanic conductivity and to which extent this could explain the observed systematic seasonal variation of tippers. Our model studies suggest that for most of the considered island observatories the effect from depth-varying oceanic conductivity is tangible and exceeds the error floor of 0.025, which usually is assigned to tippers during their inversion. The effect varies significantly with location, depending on regional bathymetry. Contrarily, the effects from seasonally varying oceanic conductivity were found to be too small to be worth consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the geophysical methods to probe the physical parameters of the Earth’s mantle is Geomagnetic Depth Sounding (GDS; Banks 1969; Weidelt 1972). GDS exploits magnetic field variations of magnetospheric and/or ionospheric origin, and allows to constrain electrical conductivity at depth. The main data source for GDS is magnetic field measurements performed at the global net of geomagnetic observatories. Long-period (> 3 h) variations are routinely used in GDS to constrain electrical conductivity of the Earth’s mantle (approximately from 400 km down to 1500 km) either in terms of local one-dimensional (1-D; Olsen 1998; Utada et al. 2003; Munch et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020, among others) or three-dimensional (3-D; Kelbert et al. 2009; Semenov and Kuvshinov 2012; Koyama et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2015; Li et al. 2020, among others) conductivity distributions.

Recent studies (Samrock and Kuvshinov 2013; Morschhauser et al. 2019) have also shown that vertical transfer functions (tippers) estimated from short-period (< 3 h) variations at island observatories can be used to constrain conductivity distribution beneath oceans, where our knowledge is still very limited. This becomes feasible due to the ocean induction effect (OIE; cf. Parkinson and Jones 1979), which originates from lateral conductivity contrasts between ocean and land. The OIE leads to non-zero tippers even for 1-D conductivity distribution beneath the ocean (cf. Samrock and Kuvshinov 2013); therefore, the inversion of island tippers can provide information on the electrical properties of the crust and upper mantle in remote oceanic regions. However, the interpretation of island tippers requires accurate 3-D electromagnetic (EM) modeling of the OIE that takes into account the bathymetry around the observatory. Hitherto, during such modeling, the researchers assumed constant oceanic electric conductivity with depth (cf. Samrock and Kuvshinov 2013; Morschhauser et al. 2019). In many regions of the world, however, oceanic conductivity varies significantly within the uppermost few hundred meters of the water column (cf. Tyler et al. 2017). In this study, we explore the extent to which realistic depth-varying oceanic conductivity affects island tippers. Our analysis is performed for 11 island observatories located in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans (cf. Fig. 1). In addition, we investigate the effect of seasonal variations of oceanic conductivity and to which extent this could explain the systematic seasonal variations in tippers investigated by Araya Vargas and Ritter (2016) and attributed to the variability of external magnetic source fields.

Location of geomagnetic observatories used in this study (green dots). Black lines depict \(\pm 55^\circ\) quasi-dipole latitudes. Relevant information about these observatories is summarized in Table 1

1-D global conductivity profile (from Grayver et al. 2017) used in this study for the crust and mantle beneath the 3-D (oceanic) modeling domains, where the top 2000 km depth is shown

Vertical parametrization of the oceanic conductivity distribution in the 3-D modeling domain. \(\sigma _{1}\) to \(\sigma _{12}\) are the respective water layer’s conductivities, set to the layer’s average conductivity calculated from the global ocean conductivity model. \(\sigma _{\text{ocean}}\) is the deep (below 2000 m) ocean conductivity, which is set to 3.2 S/m. \(\sigma _{\text{land}}\) and \(\sigma _{\text{air}}\) are the landmass and air conductivity set to 0.01 S/m and \(10^{-8}\) S/m, respectively

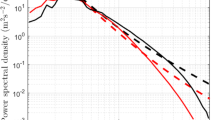

Results for Apia observatory (API). a Map of bathymetry/topography; dashed line indicates location of profile shown in b. b West–East oriented bathymetry profile. c Regional depth-varying (purple) oceanic conductivity and constant reference oceanic conductivity (3.2 S/m, orange dashed line). d–g Real and imaginary parts for x and y components of tippers computed in the model with depth-varying (red dots and dashed line) and depth-constant (orange dots and dashed line) oceanic conductivity. h Difference for the computed tipper x component between depth-varying and depth-constant ocean conductivity, see text for details. Dashed grey line indicates the threshold of 0.025. i Same as (h), but for the y component

Same as Fig. 5, but for Ascension Island observatory (ASC)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Cocos-Keeling Islands observatory (CKI)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Gan observatory (GAN)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Guam observatory (GUA)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Honolulu observatory (HON)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Easter Island observatory (IPM)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Pamatai observatory (PPT)

Same as Fig. 5, but for St. Helena observatory (SHE)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Santa-Maria/Azores observatory (SMA)

Same as Fig. 5, but for Tristan da Cunha observatory (TDC)

Methods

Tippers

In non-polar regions, the source of the magnetic field variations with periods shorter than 3 h is well approximated by a vertically incidenting plane wave. The plane-wave assumption allows one to relate the vertical component \(B_z\) with the horizontal component \({\mathbf {B}}_H = (B_x~ B_y)\) at the location r = (x,y,z) via the so-called tipper \({\mathbf {T}} = (T_{zx}~ T_{zy})\) (e.g., Berdichevsky and Dmitriev 2008):

where \(\omega = 2\pi /P\) is the angular frequency of magnetic field variations with period P. The x- and y-directions are defined in this paper as the directions to geographic North and East, respectively, and z is directed vertically downwards. As a consequence of the plane-wave excitation, \(B_z\) (and, thus, \({\mathbf {T}}\)) are non-zero only above non-1-D conductivity structures. In fact, one can interpret \({\mathbf {T}}\) as a measure of the tipping of the magnetic field out of the horizontal plane above two-dimensional or/and 3-D conductivity structures.

Global oceanic conductivity model

The global oceanic electric conductivity model used here is that by Petereit et al. (2019), which is based on the Coriolis Oceanographic data set for Re-Analysis (CORA5.0, Cabanes et al. 2013) provided by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service. The model consists of monthly 3-D oceanic electrical conductivity distributions from 1990 to 2016. The conductivity is computed on a lateral grid of \(0.5^\circ \times 0.5^\circ\) resolution and at 152 vertical levels between the sea surface and 2000 m. More details on the oceanographic data set and the calculation of the global oceanic conductivity model can be found in Petereit et al. (2019). From 2000 m down to the ocean bottom, the sea water conductivity was set to 3.2 S/m (cf. Tyler et al. 2017). As an example, Fig. 2 presents global maps of the depth-averaged oceanic conductivity for a number of depth intervals for December 2015, illustrating the fact that oceanic conductivity indeed varies laterally and with depth.

Constructing island 3-D conductivity models

The (Cartesian) 3-D conductivity models were constructed separately for each observatory. The models include a nonuniform oceanic bathymetry and a landmass with a uniform conductivity of 0.01 S/m. We decided to use the same land conductivity for all observatories as a mean representative value, since we did not succeed to find better data to set the land conductivity specific for each location. The landmass is defined here as the upper crust from the maximum elevation down to the maximum depth of the ocean in the considered region. Note that landmass conductivity of 0.01 S/m was also adopted in the previous studies (Morschhauser et al. 2019; Samrock and Kuvshinov 2013) which addressed modeling of island tippers.

The landmass and the ocean comprise the 3-D part of the model, which is underlain by a crust and mantle with the 1-D conductivity distribution (cf. Fig. 3) from Grayver et al. (2017). Their 1-D model was obtained by joint inversion of satellite-detected tidal and magnetospheric signals and is believed to represent the globally averaged 1-D conductivity profile beneath the oceans. More details on our 3-D models are as follows.

First, we note that as far as we exploit the integral equation (IE) based solver (to be discussed in the next section) to compute magnetic fields, the modeling domain is confined to the 3-D part of the model. The lateral size of the 3-D modeling domain was taken as \(356 \times 356\) km\(^2\) square with the island observatory in its center. The island was placed in the center of the modeling region (laterally) to avoid potential edge effects in the results. The vertical range of the domain is from the maximum topography down to the maximum depth of the ocean in the region of interest. The 3-D part of the models is constructed using bathymetry and topography data from the General Bathymetry Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO 2019), which is a global map compiled from a variety of sources with 15 arc sec horizontal resolution (corresponding to 0.46 km at the equator). Bathymetry/topography is converted to Cartesian coordinates by the use of the Transverse Mercator map projection and then linearly interpolated to a uniform grid with 1 km horizontal resolution. Note that we performed a comprehensive model study to justify the chosen lateral size of the modeling domain and cell sizes.

The uppermost left panel in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15 shows the bathymetry/topography in the vicinity of the corresponding island observatory. Vertically, the 3-D modeling domain was discretized in 100 m layers from the maximum topography down to 1000 m depth; from 1000 m down to the maximum bathymetry in the region, the domain was discretized in 500 m-thick layers (see Fig. 4). Oceanic conductivity within each vertical layer is assumed to be constant and is set to the 3-D average value of the 2015 December (or June) oceanic conductivity model for the layer’s volume. The models from 2015 year are chosen, since most of experimental tippers are derived from the data for this year (or adjacent years). Sedimentary layers were not incorporated into the models, since sediment thickness is negligible in the oceanic regions considered in this study (Straume et al. 2019).

Outside the 3-D volume, at depths between the surface and maximum depth of the ocean, conductivity is assumed to be laterally uniform (1-D) and is set to the same oceanic conductivity profile as inside the volume, underlain by the 1-D model for crust and mantle. The air conductivity is set to \(10^{-8}\) S/m. The uppermost right panel in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15 depicts the vertical profile of oceanic conductivity (in purple), calculated by horizontally averaging oceanic conductivity (Fig. 2) in a \(5^\circ \times 5^\circ\) region centered at the considered island observatory. The panel demonstrates that the oceanic conductivity varies significantly with depth down to approximately 1 km depth. Below this depth, the values are close to 3.2 S/m.

Furthermore, for each observatory, we construct a 3-D model with a constant oceanic conductivity of 3.2 S/m in all vertical layers. Outside the 3-D volume, the oceanic conductivity is set to 3.2 S/m, underlain by the 1-D model by Grayver et al. (2017) for crust and mantle.

Modeling tippers

We compute magnetic fields (and then tippers) using the 3-D EM forward modeling solver PGIEM2G which is based on a volume integral equation method with contracting kernel (Pankratov et al. 1995; Singer 1995), and which was presented and validated (against finite-element solver by Grayver and Kolev 2015) in Kruglyakov and Kuvshinov (2018).

We compute tippers at 25 periods spanning the range from \(10^{-1}\) to \(10^{4}\) s. Note that, nowadays, most observatories provide magnetic field data in the form of minute means. This allows researchers to estimate tippers at periods starting from approximately 300 s. However, there is a growing investment from the scientific community in providing magnetic observatory data in the form of second means, which would enable estimating tippers for periods down to a few seconds. Tippers for even smaller periods can also be estimated at observatory locations by performing a short-term (a few days) measurements with the use of induction coils; note that the standard observatory instrument to measure magnetic field variations is a fluxgate magnetometer. Bearing in mind the above considerations, we modeled tippers at periods shorter than 300 s to obtain an idea what is the smallest period at which ocean induction effect becomes noticeable.

Estimating tippers from the data

We estimated tippers at nine island geomagnetic observatories from the International Real-Time Magnetic Observatory Network (INTERMAGNET) using definite minute-mean data that are time-series of three components of magnetic field. In addition, we estimated tippers at two non-INTERMAGNET island observatories: St. Helena (SHE) and Santa-Maria/Azores (SMA), also using minute-mean data. Prior to the tipper estimation, obvious spikes were removed from the corresponding time-series. Table 1 summarizes information about the observatories, including the time interval used for the tipper estimation. This interval varies from observatory to observatory and was selected—based on a trial-and-error approach—to obtain smooth (with respect to period) tippers with low uncertainties.

For each period, data were split into overlapping tapered windows of two period length. Data in these windows were Fourier transformed, giving the spectrum of the corresponding component from 300 to 9600 s. Tippers and their uncertainties were then estimated using a robust, section-averaging (Olsen 1998) linear regression scheme based on the Huber norm (e.g., Aster et al. 2005; Püthe and Kuvshinov 2014).

Results

Effect of depth-varying oceanic conductivity

Modeling results for all 11 island observatories are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15. In the figures, panel (a) shows the bathymetry/topography map with the corresponding observatory located in the center. The dashed line indicates the West–East running bathymetry/topography profile, as shown in panel (b). Panel (c) shows the regional depth-varying oceanic conductivity down to 2000 m (purple solid line) and the constant reference oceanic conductivity (3.2 S/m, dashed orange line). Panels (d–g) present the \(\text {Re} \, T_{zx}\), \(\text {Re}\,T_{zy}\), \(\text {Im}\,T_{zx}\), and \(\text {Im}\,T_{zy}\) tipper components. Red and orange curves correspond to tippers calculated in the models with depth-varying and depth-constant oceanic electrical conductivity, respectively. The blue curves represent tippers and their uncertainties estimated from the data. One can see that both observed and modeled tippers fulfill the property (Marcuello et al. 2005) that is often used as a plausibility check for the tippers, namely, at periods where \(\text {Re} \, T_{zx}\) or \(\text {Re} \, T_{zy}\) reaches a maximum (or a minimum) value, \(\text {Im} \,T_{zx}\) or \(\text {Im}\,T_{zy}\) changes the sign. Finally, panels (h) and (i) show the effect of depth-varying oceanic conductivity on island tippers. This effect is assessed by the following difference:

where \(i \in [x,y]\), and superscripts “v” and “c” correspond to the tippers calculated in the models with depth-varying and depth-constant oceanic conductivity, respectively. Here, we consider the effect as non negligible if it exceeds a value of 0.025, which is conventionally used as an error floor in tipper inversions (e.g., Morschhauser et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2015; Tietze and Ritter 2013; Rao et al. 2014; Bedrosian and Feucht 2014) and which is shown in the panels as horizontal dashed line.

Three observations can be made from panels (d–g) that are independent of modeling being done with depth-varying or depth-constant oceanic conductivity:

-

1.

The manifestation of the OIE in the modeled tippers varies from observatory to observatory. Given that depth-varying oceanic conductivity profiles (panels (c) in all figures) present similar values for all observatories, except for SMA, this variability of the OIE is expected to be due to the different bathymetry distributions around the islands.

-

2.

Modeled and experimental tippers agree rather well for most observatories, for the full spectrum from 300 to 9600 s, for both components and for both the real and imaginary parts. Any remaining discrepancy can most probably be attributed to regional deviations of the crustal and mantle conductivity structure from the global 1-D conductivity structure used for modeling, and, partly, to limitations in bathymetry data resolution.

-

3.

The modeled OIE in tippers can be traced to periods as short as 0.2 s.

As for the effect from depth-varying oceanic conductivity, it varies from observatory to observatory, from component to component, and shows different behaviour with respect to period. This variability, like the variability of OIE itself, is expected to be from the different bathymetry distributions around the islands. The largest effect—reaching 0.15—is observed at Apia observatory in \(\text {Re}\, T_{zx}\) component.

Effect of time-varying oceanic conductivity

Figure 16 presents global maps of differences between December and June oceanic conductivity in the same depth intervals as in Fig. 2. As expected, the difference varies laterally, it is the largest at shallower depths (reaching 20 percent of the mean value of oceanic conductivity) and decreases with depth.

Finally, we modeled the effect of time-varying oceanic conductivity on island tippers. The effect is assessed by analyzing the difference:

where \(i \in [x,y]\), and superscripts “D” and “J” correspond to December and June results. For the observed (i.e., estimated from the data) tippers, December and June results stand for tippers estimated from observatory data of corresponding 2015 months. As for modeled tippers, these results mean tippers calculated in 3-D models with depth-varying oceanic conductivity models for 2015 December and June months.

In all considered observatories, modeled \(\Delta T_{zx}\) and \(\Delta T_{zy}\) are very small at all periods in the \(10^{-1}\) to \(10^{4}\) s period range. Figures 17 and 18 present observed and modeled differences as filled circles on a global map for six representative periods from 300 to 9600 s. Observed and modeled differences are colored in Fig. 17 by light and dark red, and in Fig. 18—by light and dark blue. It is clearly seen that the effect due to time-varying oceanic conductivity is negligible; indeed, the filled circles depicted the modeled difference look as “dots”. It is interesting to note that the temporal variability of the experimental tippers increases with period and, overall, it is larger in \(T_{zy}.\)

Conclusions

In this study, we performed the first ever analysis of the effects of realistic depth- and time-varying oceanic electrical conductivity on island tippers. The analysis is based on 3-D EM modeling, which was carried out for 11 island observatories located in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. The conductivity models specific for each observatory were constructed using bathymetry/topography data with the highest spatial resolution available (GEBCO 2019) and a 3-D, time-dependent and physics-based global model of oceanic conductivity (Petereit et al. 2019). The Cartesian EM forward solver by Kruglyakov and Kuvshinov (2018) was used for tippers’ modeling. Modelings were performed in wide period range (\(10^{-1} \text {to} 10^{4}\) seconds) and demonstrated that ocean induction effect in tippers can be traced to periods as short as 0.2 s.

The effect due to depth-varying oceanic conductivity was assessed by comparing the tippers obtained from the depth-varying and depth-constant oceanic conductivity models. Our model studies show that this effect is tangible in all observatories except for TDC. It exceeds the error floor of 0.025, which is usually assigned to tippers during their 2-D or 3-D inversion, and reaches values of about 0.1 at API, GAN, and HON observatories. The appearance of the effect with respect to period and its strength varies from observatory to observatory. Since depth-varying conductivity profiles are rather similar for all locations, such variability of the effect is most probably due to different bathymetry distributions around the islands.

On the contrary, the modeled effects from time-varying oceanic conductivity appeared to be too small to explain the observed seasonal variations in tippers.

It is worth noting that introducing a more complex ocean conductivity did not lead to an improvement in the agreement between modeled and experimental responses at many observatories. The most possible reason for this is a deviation of local subsurface conductivity structure from the global 1-D section used in the paper. Obviously, to improve the agreement between modeling and experimental tippers, one needs to invert tippers for each location, and thus obtain local conductivity profile beneath each island observatory. Such inversions are out of the scope of this paper, but will be the subject of future study. It is planned to invert island tippers jointly with the longer period responses (cf. Munch et al. 2020) to constrain conductivity throughout the entire depth range. The reliability of the inversions in particular depends on how accurate we represent in the model the oceanic conductivity. In this context, we believe that it is worth effort to use depth-varying oceanic conductivity during inversions provided that these data are considered to be trustworthy.

Availability of data and materials

The results presented in this paper rely on 1 Hz data collected at geomagnetic observatories. These data were digitally filtered to produce 1 min means that are available from the INTERMAGNET data repository.

Abbreviations

- EM:

-

Electromagnetic

- 1-D:

-

One-dimensional

- 2-D:

-

Two-dimensional

- 3-D:

-

Three-dimensional

- OIE:

-

Ocean induction effect

- GEBCO:

-

General Bathymetry Chart of the Oceans

- MT:

-

Magnetotellurics

References

Araya Vargas J, Ritter O (2016) Source effects in mid-latitude geomagnetic transfer functions. Geophys J Int 204(1):606–630

Aster R, Borchers B, Thurber C (2005) Parameter estimation and inverse problems. Elsevier Academic Press, Waltham

Banks RJ (1969) Geomagnetic variations and the electrical conductivity of the upper mantle. Geophys J Int 17(5):457–487

Bedrosian PA, Feucht DW (2014) Structure and tectonics of the northwestern United States from EarthScope USArray magnetotelluric data. Earth Planet Sci Lett 402:275–289

Berdichevsky MN, Dmitriev V (2008) Models and methods of magnetotellurics. Springer, Berlin

Cabanes C, Grouazel A, von Schuckmann K, Hamon M, Turpin V, Coatanoan C (2013) The CORA dataset: Validation and diagnostics of in-situ ocean temperature and salinity measurements. Ocean Sci 9(1):1–18

Chen C, Kruglyakov M, Kuvshinov A (2020) A new method for accurate and efficient modeling of the local ocean induction effects. Application to long-period responses from island geomagnetic observatories. Geophys Res Lett 47(8):e2019GL086,351. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086351

GEBCO (2019) GEBCO compilation group (2019) GEBCO 2019 grid. https://doi.org/10.5285/836f016a-33be-6ddc-e053-6c86abc0788e

Grayver AV, Kolev T (2015) Large-scale 3D geo-electromagnetic modeling using parallel adaptive high-order finite element method. Geophysics 80(6):277–291

Grayver AV, Munch FD, Kuvshinov AV, Khan A, Sabaka TJ, Tøffner-Clausen L (2017) Joint inversion of satellite-detected tidal and magnetospheric signals constrains electrical conductivity and water content of the upper mantle and transition zone. Geophys Res Lett 44(12):6074–6081

Kelbert A, Schultz A, Egbert G (2009) Global electromagnetic induction constraints on transition-zone water content variations. Nature 460:1003–1007

Koyama T, Khan A, Kuvshinov A (2014) Three-dimensional electrical conductivity structure beneath Australia from inversion of geomagnetic observatory data: evidence for lateral variations in transition-zone temperature, water content and melt. Geophys J Int 196:1330–1350. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggt455

Kruglyakov M, Kuvshinov A (2018) Using high-order polynomial basis in 3-D EM forward modeling based on volume integral equation method. Geophys J Int 213:1387–1401

Li S, Weng A., Zhang Y, Schultz A., Li Y, Tang Y, Zou Z, Zhou Z (2020) Evidence of Bermuda hot and wet upwelling from novel three-dimensional global mantle electrical conductivity image. Geochem Geophys Geosyst https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009016

Marcuello A, Queralt P, Ledo J (2005) Applications of dispersion relations to the geomagnetic transfer function. Phys Earth Planet Inter 150:85–91

Morschhauser A, Grayver AV, Kuvshinov AV, Samrock F, Matzka J (2019) Tippers at island geomagnetic observatories constrain electrical conductivity of oceanic lithosphere and upper mantle. Earth Planets Space 71(1):17

Munch FD, Grayver AV, Kuvshinov A, Khan A (2018) Stochastic inversion of geomagnetic observatory data including rigorous treatment of the ocean induction effects with implications for transition zone water content and thermal structure. J Geophys Res 123:31–51

Munch FD, Grayver AV, Guzavina M, Kuvshinov A., Khan A (2020) Joint inversion of daily and long-period transfer functions reveals lateral variations in mantle water content. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087222

Olsen N (1998) The electrical conductivity of the mantle beneath europe derived from C-responses from 3 to 720 hr. Geophys J Int 133(2):298–308

Pankratov O, Avdeev D, Kuvshinov A (1995) Electromagnetic field scattering in a heterogeneous earth: a solution to the forward problem. Izvestiya Phys Solid Earth 31(3):201–209

Parkinson W, Jones FW (1979) The geomagnetic coast effect. Rev Geophys Space Phys 17(8):1999–2017

Petereit J, Saynisch-Wagner J, Irrgang C, Thomas M (2019) Analysis of ocean-tide induced magnetic fields derived from oceanic in situ observations: climate trends and the remarkable sensitivity of shelf regions. J Geophys Res Oceans 124:8257–8270

Püthe C, Kuvshinov A (2014) Mapping 3-D mantle electrical conductivity from space: a new 3-D inversion scheme based on analysis of matrix Q-responses. Geophys J Int 197(2):768–784

Rao CK, Jones AG, Moorkamp M, Weckmann U (2014) Implications for the lithospheric geometry of the Iapetus suture beneath ireland based on electrical resistivity models from deep-probing magnetotellurics. Geophys J Int 198:737–759

Samrock F, Kuvshinov A (2013) Tipper at island observatories: can we use them to probe electrical conductivity of the earth’s crust and upper mantle? Geophys Res Lett 40:824–828

Semenov A, Kuvshinov A (2012) Global 3-D imaging of mantle electrical conductivity based on inversion of observatory C-responses—II. Data analysis and results. Geophys J Int 191(3):965–992

Singer B (1995) Method for solution of Maxwell’s equations in non-uniform media. Geophys J Int 120:590–598

Straume EO, Gaina C, Medvedev S, Hochmuth K, Gohl K, Whittaker JM, Absul Fattah R, Doornenbal JC, Hopper JR (2019) Globsed: updated total sediments thickness in the world’s oceans. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 20: 1756-1772. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GC008115

Sun J, Kelbert A, Egbert GD (2015) Ionospheric current source modeling and global geomagnetic induction using ground geomagnetic observatory data. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:6771–6796. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB012063

Tietze K, Ritter O (2013) Three-dimensional magnetotelluric inversion in practice–the electrical conductivity structure of the San Andreas fault in central California. Geophys J Int 195:130–147

Tyler RH, Boyer TP, Minami T, Zweng MM, Reagan JR (2017) Electrical conductivity of the global ocean. Earth Planets Space 69:156–166

Utada H, Koyama T, Shimizu H, Chave AD (2003) A semi-global reference model for electrical conductivity in the mid-mantle beneath the North Pacific region. Geophys Res Lett 30(4):1194–1198

Weidelt P (1972) The inverse problem of geomagnetic induction. J Geophys 38:257–289

Yang B, Egbert GD, Kelbert ANM (2015) Three-dimensional electrical resistivity of the north-central USA from EarthScope long period magnetotelluric data. Earth Planet Sci Lett 422:87–93

Zhang Y, Weng A, Li S, Yang Y, Tang Y, Liu Y (2020) Electrical conductivity in the mantle transition zone beneath Eastern China derived from L1-Norm C-responses. Geophys J Int 221(2):1110–1124. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggaa059

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge national institutes around the world that operate geomagnetic observatories, and INTERMAGNET (www.intermagnet.org) which promotes high standards of observatory practice. We also acknowledge the work of GEBCO group for providing publicly available global bathymetry data. We thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding

RR was supported by CNPq, Process 133345/2018-1. MK was supported by grant 20-05-00001 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. AK was partially supported by the European Space Agency through the Swarm DISC project. KP was supported by FAPERJ (Jovem Cientista do Nosso Estado, Process 202.748/2019). EM was supported by the state assignment of the Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth of the Russian Academy of Sciences. JP was supported by the German Research Foundation’s priority program 1788 “Dynamic Earth”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR estimated tippers from observatory data, prepared 3-D conductivity models, performed 3-D modeling, and analyzed the results. MK provided the 3-D EM modeling code PGIEM2G and assisted RR with the modeling. EM and MK provided the codes for converting global bathymetry/topography and ocean conductivity data into 3-D conductivity models. AK created the concept of the study, and AK and KP supervised the RR’s work. JP prepared global oceanic conductivity data. JM obtained and provided SHE and SMA magnetic field data. RR drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rigaud, R., Kruglyakov, M., Kuvshinov, A. et al. Exploring effects in tippers at island geomagnetic observatories due to realistic depth- and time-varying oceanic electrical conductivity. Earth Planets Space 73, 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01339-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01339-3