Abstract

Inter-station cross-correlation functions estimated using continuous ambient noise or microtremor records were used to extract the seismic wave propagation characteristics of the Osaka sedimentary basin, Japan. Temporary continuous observations were conducted at 15 sites in the Osaka basin between 2011 and 2013. The data were analyzed using seismic interferometry. The target period range was 2–8 s. Cross-correlations between all of the possible station pairs were calculated and stacked to produce a year-long data set, and Rayleigh wave signals in the vertical and radial components and Love wave signals in the transverse component were identified from the results. Simulation of inter-station Green’s functions using the finite difference method was conducted to check the performance of the current three-dimensional velocity structure model. The measured time lag between the observed and theoretical Green’s functions was less than 2 s for most station pairs, which is less than the wave period of interest in the target frequency range. Group velocity tomography was applied to group delay times estimated by means of multiple filter analysis. The estimated group velocities for longer periods of 5–8 s exhibited spatial variation within the basin, which is consistent with the bedrock depth distribution; however, the group velocities for shorter periods of 2–3 s were almost constant over the studied area. The waveform and group velocity information obtained by seismic interferometry analysis can be useful for future reconstruction of a three-dimensional velocity structure model in the Osaka basin.

.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Osaka basin in western Japan is a sedimentary basin filled by the Plio-Pleistocene Osaka Group, which is 1–3 km thick. The Osaka Group overlies Miocene and pre-Tertiary basement rocks and is discordantly overlain by terrace and alluvial deposits (e.g., Itihara et al. 1997). Ground motions in the Osaka basin are remarkably amplified and prolonged during moderate to large earthquakes (e.g., Hatayama et al. 1995; Furumura and Koketsu 1998; Asano et al. 2016b; Iwata et al. 2016). To simulate or predict the ground motions of damaging earthquakes quantitatively, a reliable velocity structure and source models for future earthquakes are indispensable. The velocity structure of the Osaka basin has been investigated extensively using geophysical and geological techniques such as gravity anomaly measurements (e.g., Nakagawa et al. 1991; Inoue et al. 1998), refraction and reflection surveys (e.g., Toriumi et al. 1990; Kagawa et al. 1990; Horike et al. 1996), offshore seismic air gun reflection surveys (e.g., Iwasaki et al. 1994; Iwabuchi et al. 2000; Ito et al. 2001), boring explorations (e.g., Ikebe et al. 1970; Yoshikawa et al. 1998; Inoue et al. 2013), microtremor measurements (e.g., Kagawa et al. 1998; Uebayashi 2003; Yoshimi 2012; Minami et al. 2014), and strong motion observations (e.g., Hatayama et al. 1995; Toki et al. 1995). Based on the results obtained using these techniques and ground motion simulations for observed moderate events, three-dimensional velocity structure models of the Osaka basin have been developed and improved over several decades (e.g., Kagawa et al. 1993, 2004; Horikawa et al. 2003; Iwata et al. 2008; Iwaki and Iwata 2011; Sekiguchi et al. 2013). Although many types of surveys have been conducted, more direct information and validation on the S-wave velocity structure is still necessary to improve the velocity structure model because the available constraints from those surveys are not distributed uniformly over the basin.

Seismic interferometry, which employs continuous ambient noise or microtremor records, is used to characterize seismic wave propagation in the Earth and has been widely applied in pure and engineering seismology on various scales (e.g., Shapiro and Campillo 2004; Sabra et al. 2005; Bensen et al. 2007; Yamanaka et al. 2010; Seats et al. 2012; Denolle et al. 2014; Hayashida et al. 2014; Lin et al. 2014; Viens et al. 2016). Ma et al. (2008) tested two community velocity models for the Los Angeles area that were developed by the Southern California Earthquake Center (SCEC) by comparing observed inter-station Green’s functions extracted by correlating the vertical components of ambient seismic noise recorded at 56 broadband stations with those simulated by the finite element method. Chimoto and Yamanaka (2011) conducted tomographic analysis to map surface wave group velocities in the southern part of the Kanto area of Japan with a cell interval of 0.125°. They used the observed group velocity data from inter-station Green’s functions estimated by means of seismic interferometry analysis of continuous microtremor data. Denolle et al. (2014), Boué et al. (2016), and Viens et al. (2016) also analyzed basin amplification in the Kanto basin in, the Tokyo metropolitan area of Japan, using ambient noise Green’s functions.

The target area of this paper is the Osaka sedimentary basin, southwest Japan, as stated in the beginning of this section. We conduct temporary seismic observations to record ambient noise or microtremors continuously at 15 sites in the Osaka basin, and we applied the seismic interferometry technique to this data set. We focus on wave propagation in the frequency range of 0.1–0.5 Hz considering characteristic ground motion amplification in the target area and the signal-to-noise ratio of signals obtained by the seismic interferometry. We compare the observed inter-station cross-correlation functions with theoretical Green’s functions simulated using a three-dimensional velocity structure model of the Osaka basin. We then estimate the spatial distribution of the surface wave group velocities using inter-station cross-correlation functions, and we examine the differences between group velocities estimated by this analysis and theoretical dispersion curves using the present velocity structure model.

Inter-station cross-correlation functions in the Osaka basin

Temporary continuous microtremor observation

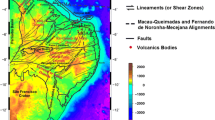

Temporary continuous observation of microtremors was conducted at 15 sites in the Osaka basin between March 2011 and March 2013 (Asano et al. 2012, 2016a). The locations of the temporary stations are shown in Fig. 1 and are listed in Table 1. The background color in Fig. 1 corresponds to the bedrock depth in the three-dimensional velocity structure model UMC2013 developed by Sekiguchi et al. (2013, 2016). The observation system at each temporary station consisted of a three-component servo velocity sensor (Tokyo Sokushin VSE-15D6, 1 V per cm/s), a 24-bit Δ–Σ-type analog-to-digital (A/D) data logger (Hakusan Corporation DATAMARK LS-8800 or LS-7000XT), and an uninterruptible power supply (UPS) unit. The velocity sensor had a flat response in the range of 0.1–70 Hz and was located on the ground surface outside or inside a garage, a small low-story building, or an observatory house. Ground motions were continuously digitized and were stored in a 32-GB secure digital high-capacity (SDHC) card (LS-8800) or a 2-GB compact flash card (LS-7000XT) at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz per channel after applying a decimation filter at 40 Hz. The timing of the data logger was continuously synchronized using the global positioning system (GPS), and the recorded data were collected regularly from the data logger.

Temporary observation stations in the Osaka basin (black triangles) shown with bedrock depths from the UMC2013 model (Sekiguchi et al. 2016)

Data processing

Continuous data recorded between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2013, were analyzed. The observed continuous time series data were divided into time segments with a duration of 30 min (1800 s), and the time segments were overlapped by 50%. The duration of a time segment was selected to capture wave propagation inside the basin originating from many sources. The time series data in each time segment were band-pass filtered between 0.05 and 2 Hz in a period range of 0.5–20 s using a Chebyshev-type recursive filter after removal of the mean. Temporal normalization was applied to the filtered waveforms to suppress the effects of earthquakes, instrumental irregularities, and local non-stationary noise sources around the stations by using the running-absolute-mean normalization method proposed by Bensen et al. (2007) with a window length of 10 s. Spectral normalization by whitening spectra was then applied to the data after calculation of the Fourier spectrum. In order to postpone the component rotation until after cross-correlation and to preserve the relative amplitude among components, the three component signals were normalized and whitened together (e.g., Lin et al. 2008, 2014). Cross-correlations for all of the possible station pairs were computed in the frequency domain. Thus, the cross-correlation or cross-spectra C ij (x A, x B, f) between the ith component of observed ground velocity at station A, v(x A, f), and the jth component of observed ground velocity at station B, v(x B, f), is given by

where f is the frequency. The denominator in the right-hand side corresponds to the spectral whitening. * Represents the complex conjugate, \(\langle {} \rangle\) indicates the ensemble average, \(| {} |\) indicates the real absolute value of the Fourier spectra, and \(\{ {} \}\) indicates the 21-point frequency running average used for spectral whitening. The inter-station distances ranged from 3.1 to 47.1 km. Cross-correlations between all possible pairs of components were computed using data from all three components including east–west, north–south, and up–down. The cross-correlation functions for all time segments were stacked in the time domain to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. Finally, the transverse–transverse (T–T), transverse–radial (T–R), transverse–vertical (T–Z), radial–transverse (R–T), radial–radial (R–R), radial–vertical (R–Z), vertical–transverse (Z–T), and vertical–radial (Z–R) components of the cross-correlation were calculated by rotating the original nine components of the cross-correlation (e.g., Lin et al. 2008). For example, the Z–R component represents the cross-correlation between the vertical component of the record at station A and the radial component of the record at station B, which corresponds to the radial component of the medium response at station B caused by a unit force in the vertical direction excited at station A. Because the ground velocities observed from the velocity-type sensors are analyzed throughout this study, the cross-correlation of the velocity wavefields at two stations is proportional to the superposition of causal and acausal velocity Green’s functions (e.g., Wapenaar and Fokkema 2006).

Obtained inter-station cross-correlation functions

Examples of nine components of the obtained inter-station cross-correlation functions are shown in Fig. 2. All of the components in this figure were band-pass filtered between 0.1 and 0.5 Hz considering the signal-to-noise ratio of the obtained signals. The predominant signal visible in the T–T component was outstanding among the nine components for most station pairs, which was likely caused by the surface wave excitation and propagation characteristics of the Osaka basin. Figure 3 displays monthly stacked inter-station cross-correlation functions (T–T and R–R components) in the same frequency range for the station pair UEMC06–UEMC09, the inter-station distance of which was 31.6 km. For this station pair, the seasonal variation in the obtained cross-correlation functions was not significant. This seasonal stability was quite common in our data set.

(Top) Nine components of the inter-station cross-correlation functions obtained in the frequency range 0.1–0.5 Hz for station pairs a UEMC06–UEMC09 and d UEMC05–UEMC13. The hatched area indicates the time window for plotting the particle motion. (Bottom) Particle motion of the causal part in the b, e R–Z and c, f T–R planes for the same station pairs

Monthly stacked inter-station cross-correlation functions for transverse–transverse (T–T) components (left) and radial–radial (R–R) components (right) in the frequency range 0.1–0.5 Hz for station pair UEMC06–UEMC09. The four-digit number on the left of a trace indicates the month and year corresponding to the trace (e.g., 1303 means March 2013). The number on the right of a trace represents the number of time segments stacked to produce the stacked cross-correlation function

Figure 4 shows the T–T, R–R, and Z–Z components of the obtained inter-station cross-correlation functions for all of the station pairs as a record section with respect to the inter-station distance. These components were filtered in the range of 0.1–0.5 Hz. Clear propagation signals could be recognized from these plots by both positive and negative correlation lags. The particle motions of predominant signals, which are indicated by the hatched area in Fig. 2a, d, were analyzed. The particle motion on the R–Z plane (vertical plane) due to radial force (Fig. 2b, e) showed clear retrograde motion. This result indicates that the predominant signal corresponds to the fundamental mode of the Rayleigh wave. The vertical component of these particle motions is relatively smaller than the radial component for most station pairs primarily because the ellipticity of the Rayleigh wave is nearly flat around the dominant frequency of the basin amplification.

The transverse component dominated the particle motion on the T–R plane (horizontal plane) due to transverse force (Fig. 2c, f). We inferred that the predominant wave packet or phase in the T–T component is the fundamental mode of the Love wave. Because no other significant wave packet was visible in the obtained T–T signals, the higher modes of the Love wave were not strongly excited in this frequency range; thus, it would have existed only at higher frequencies. The outstanding fundamental Love wave is consistent with the observational and theoretical study by Hatayama et al. (1995). They reported that the fundamental mode of the Love wave predominant in the later part of the observed ground motion in the Osaka basin was excited by large, deep earthquakes and that the first higher mode of the basin-induced Love wave cannot exist in frequencies less than 0.5 Hz in the central part of the basin. On the contrary, Boué et al. (2016) reported clear excitation of the first and second higher modes of the Love wave in the Kanto basin, southeast Japan, based on ambient noise Green’s functions in the frequency range of 0.25–0.5 Hz. The Kanto basin contains thick Neogene sediments of the Miura group above pre-Neogene bedrock (Ito et al. 2016). The S-wave velocity inside the basin gradually increases with depth (e.g., Takemura et al. 2015). The Osaka basin is smaller than the Kanto basin and has a clear unconformity at the sediment–bedrock boundary with a large jump in S-wave velocity. The S-wave velocity in the sediments is less than 1.0 km/s (e.g., Sekiguchi et al. 2016). The difference of the velocity structure in the sedimentary basin would cause a difference in excitation of the modes.

The resulting cross-correlations were two-sided time functions with both positive (causal) and negative (acausal) time coordinates or correlation lags. If the sources of microtremors are distributed homogeneously in the azimuth, the causal and acausal signals should be identical. However, considerable asymmetry in the amplitude and spectral content was occasionally observed, which indicates differences in both the source process including the frequency characteristics and the radial distance to the source from the stations (e.g., Bensen et al. 2007). Despite the difference in amplitude of prominent signals between the causal and acausal parts, the phase information in these parts was identical (Fig. 5). This fact indicates that the travel time or phase information could be reasonably extracted from our data set. Therefore, we compressed two-sided signals into one-sided signals by averaging the causal and acausal parts of the cross-correlation functions to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of the obtained inter-station cross-correlation functions. This operation has been commonly used in a variety of applications of the seismic interferometry technique (e.g., Bensen et al. 2007; Lin et al. 2008, 2014; Yamanaka et al. 2010; Hayashida et al. 2014). The resulting time series was used to approximate the inter-station Green’s function between two stations.

Comparison of the causal and acausal parts of the obtained inter-station cross-correlation functions for two station pairs (UEMC06–UEMC09 and UEMC05–UEMC13). Black and blue traces represent the causal and acausal parts, respectively. The R–R and T–T components in five different frequency ranges are presented

Validation of present velocity structure model in the Osaka basin

Simulation of Green’s function using the finite difference method

Validation of the velocity structure model is important for improving the accuracy and reliability of scenario-based strong motion prediction in sedimentary basins and plains. A traditional method of validating a model is numerical simulation of ground motion excited by small to large earthquakes (e.g., Aagaard et al. 2008; Aoi et al. 2008; Iwaki and Iwata 2010; Dhakal and Yamanaka 2013; Maufroy et al. 2015; Asano et al. 2016b; Guo et al. 2016; Taborda et al. 2016). For modeling a real earthquake, the source model and wave propagation outside the target area should be examined. The azimuthal coverage of sources depends on the seismicity of the target area. Currently, inter-station Green’s functions are used to validate three-dimensional seismic velocity structure models as an alternative to ground motion records of real earthquakes (e.g., Ma et al. 2008; Asano et al. 2011; Gao and Shen 2012). By using waveform information of inter-station Green’s functions, we can obtain good spatial coverage of the ray path across the basin, and we can focus on wave propagation characteristics inside the basin. These points are significant for using inter-station Green’s functions in the validation of velocity structure models.

Theoretical inter-station Green’s functions were simulated using the present three-dimensional velocity structure model UMC2013 (Sekiguchi et al. 2013, 2016) to assess the effectiveness in the present model in explaining the observed characteristics of surface wave propagation in the Osaka basin. This velocity structure model was developed on the basis of geological strata, 60 reflection surveys, 89 deep boring exploration logs, phase–velocity curves obtained from 65 microtremor array measurements, dominant frequencies of microtremor H/V spectra at 110 sites, and PS–P time measurements obtained from receiver function analysis of event records at 82 strong motion stations (Sekiguchi et al. 2016). The velocity model is a function of burial depth and depositional age. The minimum P-wave and S-wave velocities of the model were 1.5 and 0.25 km/s, respectively. A detailed description of this model has been given by Sekiguchi et al. (2016). This velocity structure model was used by Asano et al. (2016b) to simulate ground motions during an M W 5.8 inland crustal earthquake that occurred on Awaji Island near the western boundary of the Osaka basin.

Theoretical Green’s functions were computed by using the finite difference method (FDM). The FDM simulation technique used and the implementation of the UMC2013 model were the same as those described in Asano et al. (2016b). Essentially, a staggered-grid FDM scheme in a velocity–stress formulation with fourth-order accuracy in space and second-order accuracy in time was used to solve elastodynamic wave equations. A zero-stress formulation was introduced for the free surface boundary condition at the top of the model space (e.g., Levander 1988; Graves 1996). A multi-axial perfectly matched layer (PML) was applied to the model boundaries, except for the free surface, to avoid non-physical reflections (Meza-Fajardo and Papageorgiou 2008; Zeng et al. 2011). The grid thickness of the PML domain was set to 10 grids. Anelastic attenuation in the medium was included in the form of a linear frequency-dependent Q operator Q(f) = Q 0(f/f 0) following the method proposed by Graves (1996). The quality factor Q 0 at the reference frequency f 0 = 0.2 Hz was determined from Q 0 = 0.3 V S for the sediments, where V S is the S-wave velocity (Asano et al. 2016b). The source was given by a single force excited on the ground surface at each station. The source time function was represented by a pseudo delta function (Herrmann 1979). Three cases consisting of vertical, radial, and transverse single forces were simulated for each source location.

The FDM model space, occupying an area of 80 km (E–W) × 70 km (N–S) in and adjacent to the Osaka sedimentary basin and corresponding to the geographical area shown in Fig. 1, extends to a depth of 25.5 km below the ground surface, or the free surface. The model was discretized using a uniform 0.05 km grid along the horizontal and vertical axes with the number of grid points at 1601 × 1401 × 512 = 1,148,416,512. Because the elevation inside the land area of the Osaka basin is less than one grid size, our simulation did not consider surface topography. Three-dimensional wave propagation was simulated for 180 s after the origin time at increments of 0.0025 s. The total number of time steps in this simulation was 72,000.

Comparison with synthetic Green’s functions

Figure 6a shows the transverse component of the theoretical Green’s functions simulated by the FDM at 14 stations due to a transverse single force at station UEMC09, with observed inter-station cross-correlation functions. A comparison of three different frequency bands (0.125–0.177, 0.177–0.250, and 0.250–0.354 Hz) is shown in the figure. The timing and waveform shape for the propagating Love wave, indicated by the red arrow, were reproduced well for most stations, particularly in the lower frequency ranges. A small difference in timing between the observed and theoretical Green’s functions was observed for some stations. Figure 6b, c shows the radial and vertical components of the theoretical Green’s functions at the same stations due to a single radial force at station UEMC09 with the observed inter-station cross-correlation functions. A propagating Rayleigh wave, indicated by the blue arrow, was also reproduced well, and the group velocity of the Rayleigh wave was faster than that of the Love wave at those stations. The FDM simulation confirmed that the Rayleigh wave was dominant in the radial rather than vertical component in these frequency bands. Additional clear wave packets, indicated by the purple arrow in Fig. 6b, occurred after the propagating wave corresponding to the Rayleigh wave-type signal at some stations such as UEMC03, UEMC04, UEMC05, UEMC06, and UEMC07. These secondary wave packets were also visible in the vertical component with small amplitudes and a 90° phase shift for some stations such as UEMC03, UEMC04, and UEMC07. These waves arrived slightly later than the Love wave, particularly at 0.177–0.250 Hz. The FDM simulation also reproduced these secondary wave packets, which supports that these signals were caused by effects of the velocity structure. These secondary arrivals may have been caused by multipathing or secondary generation of surface waves due to the three-dimensional velocity structure. Ray bending might also have contributed to Love wave visibility in the radial component to a greater or lesser extent. Interpretation of complicated wavefields in a real three-dimensional structure is not simple; therefore, direct comparison between the inter-station Green’s function and numerical simulation is a powerful method for validation of existing velocity structure models. In the frequency range of 0.250–0.354 Hz, some of the stations exhibited poor correlation between the observed and theoretical Green’s functions, which indicates that there is still room for improvement in the present velocity structure model.

Comparison of inter-station Green’s functions from ambient noise cross-correlations (black) with synthetic (red) assuming a single force excited at UEMC09. Both waveforms were band-pass filtered between 0.125 and 0.177 Hz (left), 0.177 and 0.250 Hz (middle), and 0.250 and 0.354 Hz (right). The inter-station distance is indicated below the station name. a Transverse component due to a single force in direction T+. The amplitude is normalized by the maximum amplitude of the transverse component. The red arrow indicates the fundamental mode of the Love wave. b Radial component due to a single force in direction R+. The amplitude is normalized by the maximum amplitude of the radial component. The blue arrow indicates the fundamental mode of the Rayleigh wave. The purple arrow indicates the secondary prominent wave packet. c Vertical component due to a single force in direction R+. The amplitude is normalized by the maximum amplitude of the radial component

We then measured the time lags between the observed and theoretical Green’s functions based on the cross-correlation coefficients between them. The spatial variation in the time lags is indicative of the difference between the present velocity structure model and the true velocity structure. The results for four source locations (UEMC03, UEMC06, UEMC09, and UEMC15) are shown in Fig. 7. In two frequency ranges (0.125–0.177 and 0.177–0.250 Hz), the measured time lags were less than 2 s for most station pairs, which is shorter than the wave period of interest. This map indicates that stations close to basin–mountain boundaries or hilly areas exhibited relatively worse results than other stations.

Maps showing time lags between the observed and synthetic inter-station Green’s functions in two frequency ranges, 0.125–0.177 and 0.177–0.250 Hz, assuming a single force in the directions R+ and T+ at stations UEMC03, UEMC06, UEMC09, and UEMC15. The red (blue) circle indicates that the synthetic arrives later (earlier). The radius of the circle corresponds to the amplitude of the time lag

Surface wave group velocity tomography

Method

The group delay time of the surface wave at each period was estimated using the multiple filter analysis technique (Dziewonski et al. 1969). The cross-term approach proposed by Takagi et al. (2014) was used to extract or enhance the surface wave term for the radial component and to suppress any other undesirable signals such as body waves and noise. The cross-term (ZR–RZ)/2 for all pairs is shown as a record section in Fig. 4. The estimated Love and Rayleigh wave group velocities for four station pairs are plotted with the normalized amplitude at each period in Fig. 8. The peak time corresponding to the fundamental mode was visually identified in this analysis by noting the continuity of the dispersion curve one by one. An amplitude possibly corresponding to the first higher mode was visible in the shorter period range for some station pairs. For example, the Rayleigh wave for the UEMC06–UEMC08 pair showed a clear signal having relatively faster group velocity (approximately 0.5–0.7 km/s) in the period range of 0.1–3 s (Fig. 8). At times, it was difficult to identify the group velocity of the fundamental mode at a period for a pair. To avoid misidentification of modes, we did not include such a pair in further analysis. Examples of average group velocities along the ray path at four different periods are mapped in Fig. 9. The spatial variation in the estimated group velocities is roughly consistent with the bedrock depth change in the Osaka basin (Fig. 1). Station pairs across thick sediments exhibited relatively lower group velocities, particularly in the long period range (>5 s).

We then analyzed the estimated group delay time to map group velocities in a horizontal space. We discretized the studied area with a uniform cell of 4 km in the east–west direction and 4 km in the north–south direction. The reciprocal of the group velocity was the model parameter for each cell, and the ray path between two stations was approximated by a straight line. The observational equation for this problem is

where T gk , d ik , and s i are the group delay time along the ray path for station pair k, the distance crossing cell i of ray path k, and the reciprocal of the group velocity in cell i, respectively. Summation was made for all of the cells along the ray path. The observational Eq. (2) can be written in matrix form as

The two-dimensional Laplacian smoothing constraint equation \(\Delta s_{i} = 0\) (e.g., Lees and Crosson 1989) was introduced to stabilize the solution in space:

where L is the two-dimensional finite difference Laplacian operator. Equations (3) and (4) are simultaneously solved as

The hyperparameter λ is used to control the relative weight of the spatial smoothing with respect to the observational equations, which can be objectively determined on the basis of Akaike’s Bayesian information criterion (ABIC; Akaike 1980):

where M, M s, and N are the numbers of data points, smoothing constraint equations, and model parameters, respectively; \({\tilde{\mathbf{s}}}\) is the estimated value of the model parameter vector s; and C is a constant independent of the model parameters and the hyperparameter. The system of equations was solved by using the nonnegative least squares method (Lawson and Hanson 1974). The value of the hyperparameter λ was selected to minimize the ABIC value.

Results and discussion

Figure 10 shows a map of the estimated group velocities of the Love wave for each period from 8.1 to 2.1 s; the same is shown in Fig. 11 for the Rayleigh wave. The group velocity in the longer period was generally sensitive to the deeper velocity structure and exhibited significant spatial variation. Their spatial patterns resembled the bedrock depth variation in the Osaka basin (Fig. 1). For shorter periods, a nearly uniform distribution of the group velocity was obtained. However, the area along the Osaka Bay exhibited a slightly smaller group velocity of approximately 0.3 km/s, even in the period range of 2–3 s. The spatial variation of the group velocity in the shorter period reflects the thickness of alluvial deposits.

To examine the estimated group velocity with respect to the present three-dimensional velocity model, we plotted the estimated dispersion curve together with the theoretical dispersion curves calculated by assuming one-dimensional velocity structure models extracted from the UMC2013 model (Fig. 12). The theoretical dispersion curve was calculated by using the DISPER80 program package (Saito 1988). In this plot, theoretical dispersion curves were calculated for 16 points that were uniformly sampled at an interval of 1 km in a 4 km × 4 km cell to show the variation within a cell. Figure 12 shows examples for three cells. The theoretical dispersion curves calculated from the previous model (Iwata et al. 2008), which was constructed by a different approach of modeling, are also presented in this figure for comparison. For cells (5, 6) and (8, 4), the estimated group velocities in the period range of 1.5–8 s were in good agreement with the theoretical dispersion curves of the fundamental mode of the Love and Rayleigh waves. This result validates the present velocity structure model in this area. The current UMC2013 model showed better performance than the previous model of Iwata et al. (2008).

Comparison among Love and Rayleigh wave group velocities (open circles) estimated from tomography analysis and the theoretical dispersion curves from the UMC2013 model (red line) and Iwata et al. (2008) model (blue line) at cells (I x , I y ) = (2, 5), (5, 6), and (8, 4), where I x and I y are the number of cells in the X and Y directions, respectively, as shown on the map. The S-wave velocity profiles corresponding to theoretical dispersion curves are shown in the right column

In contrast, cell (2, 5) exhibited a large discrepancy between the estimated and theoretical dispersion curves in the middle period range. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the accuracy of the velocity structure was insufficient owing to the limited amount of information available for use in developing the present model in that area. In addition, the actual bedrock depth might be deeper than the present velocity structure model. The observed period of the Airy phase, which shows the minimum group velocity, was approximately 4 s for the Love wave in this cell; thus, the actual depth of the bedrock is between 0.5 and 1.0 km. However, possible reasons that might affect the estimation of group velocity itself must be considered. Few ray paths crossed this cell because it is close to the edge of the study area, and the dispersion curve constructed from the ambient noise cross-correlation was averaged over several cells along the station-to-station path. The assumption of straight ray paths in the tomographic analysis would result in some error in estimating the group velocity when significant spatial variation is present in the seismic wave velocity.

For future reconstruction of the three-dimensional velocity structure model in the Osaka sedimentary basin, utilization of waveform information from inter-station Green’s functions through waveform modeling is a direct and straightforward method because it can naturally include three-dimensional effects on wave propagation such as ray bending, multipathing, mode conversion, and generation of basin edge-induced surface waves. Nevertheless, surface wave group velocity tomography is also a useful tool for identifying area in which further effort should be made to improve the current velocity structure model by comparing inverted and theoretical dispersion curves. The number of ray paths for the Rayleigh wave used in our work is about two-thirds of that for the Love wave because of the difficulty in identifying the fundamental mode. Because mode misidentification is critical for the Rayleigh wave, as discussed by Boaga et al. (2013), and the T–T cross-correlation function (Love wave) dominates the data set in the Osaka basin, it is better to emphasize the Love wave rather than the Rayleigh wave to analyze the velocity structure model. It is widely accepted that the combined use of a variety of observation information leads to a robust model because each survey technique has unique advantages and weaknesses. We believe the inter-station Green’s functions and surface wave group velocity data will contribute to reconstruction of the three-dimensional velocity structure model of the Osaka sedimentary basin as well as other existing survey results.

Conclusions

Inter-station cross-correlation functions estimated using continuous ambient noise or microtremor records observed at 15 temporary stations were used to extract the seismic wave propagation characteristics of the Osaka sedimentary basin. Cross-correlations between all of the possible pairs were calculated and stacked to obtain a year-long data sequence. The resulting cross-correlation functions were found to have Rayleigh wave signals in the vertical and radial components and Love wave signals in the transverse component. Theoretical Green’s functions calculated by the FDM using the latest three-dimensional velocity structure model reproduced the characteristics of the observed inter-station cross-correlation functions. Three-dimensional effects on surface wave propagation emerged as contributions of the Love wave in the radial component. The measured time lag between the observed and theoretical Green’s functions was less than 2 s for most station pairs, which is less than the wave period of interest in the target frequency range of 0.125–0.250 Hz.

The group delay time of surface waves at each period was estimated using the multiple filter analysis technique. We applied group velocity tomography to the group delay time data. The estimated group velocity for longer periods of 5–8 s exhibited significant spatial variation within the basin that was roughly consistent with the bedrock depth distribution. The group velocity for shorter periods of 2–3 s was almost constant over the studied area. A comparison of the estimated dispersion curve and the theoretical dispersion curve calculated from the present velocity structure model would help to identify areas in which further improvement in the model is necessary.

References

Aagaard BT, Brocher TM, Dolenc D, Dreger D, Graves RW, Harmsen S, Hartzell S, Larsen S, Zoback ML (2008) Ground-motion modeling of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Part I: validation using the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Bull Seismol Soc Am 98(2):989–1011. doi:10.1785/0120060409

Akaike H (1980) Likelihood and the Bayes procedure. Trab Estad Invest Oper 31(1):143–166. doi:10.1007/BF02888350

Aoi S, Honda R, Morikawa N, Sekiguchi H, Suzuki H, Hayakawa Y, Kunugi T, Fujiwara H (2008) Three-dimensional finite difference simulation of long-period ground motions for the 2003 Tokachi-oki, Japan, earthquake. J Geophys Res 113(7):B07302. doi:10.1029/2007JB005452

Asano K, Iwaki A, Iwata T (2011) Estimation of interstation Green’s functions in the long-period range (2–10 s) from continuous records of F-net broadband seismograph network in southwestern Japan. In: Proceedings of the 4th IASPEI/IAEE international symposium on effects of surface geology on seismic motion, Santa Barbara, 23–26 August 2011

Asano K, Iwata T, Sekiguchi H (2012) Application of seismic interferometry in the Osaka basin for validating the three-dimensional basin velocity structure model. In: Proceedings of the 15th world conference on earthquake engineering, Lisbon, 24–28 September 2012

Asano K, Iwata T, Sekiguchi H, Somei K, Miyakoshi K, Aoi S, Kunugi T (2016a) Surface wave group velocity tomography in the Osaka sedimentary basin, Japan, using ambient noise cross-correlation functions. In: Proceedings of the 5th IASPEI/IAEE international symposium on effects of surface geology on seismic motion, Taipei, 15–17 August 2016

Asano K, Sekiguchi H, Iwata T, Yoshimi M, Hayashida T, Saomoto H, Horikawa H (2016b) Modelling of wave propagation and attenuation in the Osaka sedimentary basin, western Japan, during the 2013 Awaji Island earthquake. Geophys J Int 204(3):1678–1694. doi:10.1093/gji/ggv543

Bensen GD, Ritzwoller MH, Barmin MP, Levshin AL, Lin F, Moschetti MP, Shapiro NM, Yang Y (2007) Processing seismic ambient noise data to obtain reliable broad-band surface wave dispersion measurements. Geophys J Int 169(3):1239–1260. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03374.x

Boaga J, Cassiani G, Strobbia CL, Vignoli G (2013) Mode misidentification in Rayleigh waves: ellipticity as a cause and a cure. Geophysics 78(4):EN17–EN18. doi:10.1190/GEO2012-0194.1

Boué P, Denolle M, Hirata N, Nakagawa S, Beroza GC (2016) Beyond basin resonance: characterizing wave propagation using a dense array and the ambient seismic field. Geophys J Int 206(2):1261–1272. doi:10.1093/gji/ggw205

Chimoto K, Yamanaka H (2011) Tomographic analysis of surface wave slowness estimated with seismic interferometric processing of continuous microtremor data in the southern Kanto area, Japan. BUTSURI-TANSA (Geophys Explor) 64(5):331–343. doi:10.3124/segj.64.331 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Denolle MA, Miyake H, Nakagawa S, Hirata N, Beroza GC (2014) Long-period seismic amplification in the Kanto Basin from the ambient seismic field. Geophys Res Lett 41(7):2319–2325. doi:10.1002/2014GL059425

Dhakal Y, Yamanaka H (2013) An evaluation of 3-D velocity models of the Kanto basin for long-period ground motion simulations. J Seismol 17(3):1073–1102. doi:10.1007/s10950-013-9373-4

Dziewonski A, Bloch S, Landisman M (1969) A technique for the analysis of transient seismic signals. Bull Seismol Soc Am 59(1):427–444

Furumura T, Koketsu K (1998) Specific distribution of ground motion during the 1995 Kobe earthquake and its generation mechanism. Geophys Res Lett 25(6):785–788. doi:10.1029/98GL50418

Gao H, Shen Y (2012) Validation of shear-wave velocity models of the Pacific Northwest. Bull Seismol Soc Am 102(6):2611–2621. doi:10.1785/0120110336

Graves RW (1996) Simulating seismic wave propagation in 3D elastic media using staggered-grid finite differences. Bull Seismol Soc Am 86(4):1091–1106

Guo Y, Koketsu K, Miyake H (2016) Propagation mechanism of long-period ground motions for offshore earthquakes along the Nankai trough: effects of the accretionary wedge. Bull Seismol Soc Am 106(3):1176–1197. doi:10.1785/0120150315

Hatayama K, Matsunami K, Iwata T, Irikura K (1995) Basin-induced Love waves in the eastern part of the Osaka basin. J Phys Earth 43(2):131–155. doi:10.4294/jpe1952.43.131

Hayashida T, Yoshimi M, Horikawa H (2014) Estimation of surface wave group velocity beneath the Chukyo area, Japan. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 66(4):127–145. doi:10.4294/zisin.66.127 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Herrmann RB (1979) SH-wave generation by dislocation source—a numerical study. Bull Seismol Soc Am 69(1):1–15

Horikawa H, Mizuno K, Ishiyama T, Satake K, Sekiguchi H, Kase Y, Sugiyama Y, Yokota H, Suehiro M, Yokokura T, Iwabuchi Y, Kitada N, Pitarka A (2003) A three-dimensional subsurface structure model beneath the Osaka sedimentary basin, southwest Japan, with fault-related structural discontinuities. Ann Report Active Fault Paleoearthquake Res Geol Survey Japan 3:225–259 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Horike M, Takeuchi Y, Imai S, Fuzita T, Yokota H, Noda T, Ikawa T (1996) Survey of the subsurface structure in the east of Osaka basin. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 49(2):193–203. doi:10.4294/zisin1948.49.2_193 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Ikebe N, Iwatsu J, Takenaka J (1970) Quaternary geology of Osaka with special reference to land subsidence. J Geosci Osaka City Univ 13:39–98

Inoue N, Nakagawa K, Ryoki K (1998) Gravity anomalies and basement structure in Osaka plain. BUTSURI-TANSA (Geophys Explor) 51(1):1–16 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Inoue N, Kitada N, Takemura K, Fukuda K, Emura T (2013) Three-dimensional subsurface structure model of Kansai International Airport by integration of borehole data and seismic profiles. Geotech Geol Eng 31(3):881–890. doi:10.1007/s10706-012-9568-4

Itihara M, Yoshikawa S, Kamei T (1997) The Pliocene–Pleistocene boundary in Japan: the Osaka Group, Kinki district. In: Van Couvering JA (ed) The Pleistocene boundary and beginning of the Quaternary. World and regional geology, vol 9. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 239–243. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511585760.026

Ito Y, Takemura K, Kawabata D, Tanaka Y, Nakaseko K (2001) Quaternary tectonic warping and strata formation in the southern Osaka Basin inferred from reflection seismic interpretation and borehole sequences. J Asian Earth Sci 20(1):45–58. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(01)00019-0

Ito M, Kameo K, Satoguchi Y, Masuda F, Hiroki Y, Takano O, Nakajima T, Suzuki N (2016) Neogene–Quaternary sedimentary successions. In: Moreno T, Wallis S, Kojima T, Gibbons W (eds) The geology of Japan. Geological Society of London, London, pp 309–337

Iwabuchi Y, Nishikawa H, Noda N, Yukimatsu T, Taga M, Miyano M, Sakai K, Fukazawa M (2000) Basement and active structures revealed by the seismic reflection survey in Osaka bay. Rep Hydrogr Res 36:1–23 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Iwaki A, Iwata T (2010) Simulation of long-period ground motion in the Osaka sedimentary basin: performance estimation and the basin structure effects. Geophys J Int 181(2):1062–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04556.x

Iwaki A, Iwata T (2011) Estimation of three-dimensional boundary shape of the Osaka sedimentary basin by waveform inversion. Geophys J Int 186(3):1255–1278. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05102.x

Iwasaki Y, Kagawa T, Sawada S, Matsuyama N, Ohshima K, Ikawa T, Onishi M (1994) Basement structure by air-gun reflection survey in Osaka Bay, Southwest Japan. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 46(4):395–403. doi:10.4294/zisin1948.46.4_395 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Iwata T, Kagawa T, Petukhin A, Ohnishi Y (2008) Basin and crustal velocity structure models for the simulation of strong ground motions in the Kinki area, Japan. J Seism 12(2):223–234. doi:10.1007/s10950-007-9086-7

Iwata T, Kubo H, Asano K, Sato K, Aoi S (2016) Long-period ground motion characteristics and simulations in the Osaka basin during the 2011 great Tohoku earthquake. In: Proceedings of the 5th international symposium for effects of surface geology on seismic motion, Taipei, 15–17 August, 2016

Kagawa T, Sawada S, Iwasaki Y, Emi S (1990) Underground velocity structure of Osaka basin upon explosion refraction data. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 43(4):527–537. doi:10.4294/zisin1948.51.1_31 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Kagawa T, Sawada S, Iwasaki Y, Nanjo A (1993) Modeling the deep sedimentary structure in the Osaka basin. In: Proceedings of the 22nd JSCE earthquake engineering symposium, Kyoto, 26–28 July 1993. doi:10.2208/proee1957.22.199 (in Japanese)

Kagawa T, Sawada S, Iwasaki Y, Nanjo A (1998) S-wave velocity structure model of the Osaka sedimentary basin derived from microtremor array observations. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 51(1):31–40. doi:10.4294/zisin1948.51.1_31 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Kagawa T, Zhao B, Miyakoshi K, Irikura K (2004) Modeling of 3D basin structures for seismic wave simulations of the Osaka basin. Bull Seismol Soc Am 94(4):1353–1368. doi:10.1785/012003165

Lawson CL, Hanson RJ (1974) Solving least squares problems. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Lees JM, Crosson RS (1989) Tomographic inversion for three-dimensional velocity structure at Mount St. Helens using earthquake data. J Geophys Res 94(B5):5716–5728. doi:10.1029/JB094iB05p05716

Levander AR (1988) Fourth-order finite-difference P-SV seismograms. Geophysics 53(11):1425–1436. doi:10.1190/1.1442422

Lin F-C, Moschetti MP, Ritzwoller MH (2008) Surface wave tomography of the western United States from ambient seismic noise: Rayleigh and Love wave phase velocity map. Geophys J Int 173(1):281–298. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2008.03720.x

Lin F-C, Tsai TC, Schmandt B (2014) 3-D crustal structure of the western United States: application of Rayleigh-wave ellipticity extracted from noise cross-correlations. Geophys J Int 198(2):656–670. doi:10.1093/gji/ggu160

Ma S, Prieto GA, Beroza GC (2008) Testing community velocity models for southern California using the ambient seismic field. Bull Seismol Soc Am 98(6):2694–2714. doi:10.1785/0120080947

Maufroy E, Chaljub E, Hollender F, Kristek J, Moczo P, Klin P, Priolo E, Iwaki A, Iwata T, Etienne V, De Martin F, Theodoulidis NP, Manakou M, Guyonnet-Benaize C, Pitilakis K, Bard P-Y (2015) Earthquake ground motion in the Mygdonian basin, Greece: the E2VP verification and validation of 3D numerical simulation up to 4 Hz. Bull Seismol Soc Am 105(3):1398–1418. doi:10.1785/0120140228

Meza-Fajardo KC, Papageorgiou AS (2008) A nonconvolutional, splitfield, perfectly matched layer for wave propagation in isotropic and anisotropic elastic media: stability analysis. Bull Seismol Soc Am 98(4):1811–1836. doi:10.1785/0120070223

Minami Y, Mizuochi Y, Matsuoka T, Haraguchi T, Motoki K (2014) Deep S-wave velocity structure in Osaka plains urban area estimated by microtremor survey method. J Jpn Soc Eng Geol 55(3):110–117. doi:10.5110/jjseg.55.110 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Nakagawa K, Ryoki K, Muto N, Nishimura S, Ito K (1991) Gravity anomaly map and inferred basement structure in Osaka Plain, Central Kinki, Southwest Japan. J Geosci Osaka City Univ 34:103–117

Sabra KG, Gerstoft P, Roux P, Kuperman WA, Fehler MC (2005) Extracting time-domain Green’s function estimates from ambient seismic noise. Geophys Res Lett 32(3):L03310. doi:10.1029/2004GL021862

Saito M (1988) DISPER80: a subroutine package for the calculation of seismic normal mode solutions. In: Doornbos DJ (ed) Seismological algorithms: computational methods and computer programs. Academic Press, London

Seats KJ, Lawrence JF, Prieto GA (2012) Improved ambient noise correlation functions using Welch’s method. Geophys J Int 188(2):513–523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05263.x

Sekiguchi H, Yoshimi M, Asano K, Horikawa H, Saomoto H, Hayashida T, Iwata T (2013) Newly developed 3D velocity structure model of the Osaka sedimentary basin. In: Abstracts of Japan Geoscience Union meeting, Chiba, 19–24 May 2013

Sekiguchi H, Asano K, Iwata T, Yoshimi M, Horikawa H, Saomoto H, Hayashida T (2016) Construction of 3D velocity structure model of Osaka sedimentary basin. In: Proceedings of the 5th international symposium for effects of surface geology on seismic motion, Taipei, 15–17 August, 2016

Shapiro NM, Campillo M (2004) Emergence of broadband Rayleigh waves from correlations of the ambient seismic noise. Geophys Res Lett 31(7):L07614. doi:10.1029/2004GL019491

Taborda R, Azizzadeh-Roodpish S, Khoshnevis N, Cheng K (2016) Evaluation of the southern California seismic velocity model through simulation of recorded events. Geophys J Int 205(3):1342–1364. doi:10.1093/gji/ggw085

Takagi R, Nakahara H, Kono T, Okada T (2014) Separating body and Rayleigh waves with cross terms of the cross-correlation tensor of ambient noise. J Geophys Res 119(3):2005–2018. doi:10.1002/2013JB010824

Takemura S, Akatsu M, Masuda K, Kajikawa K, Yoshimoto K (2015) Long-period ground motions in a laterally inhomogeneous large sedimentary basin: observations and model simulations of long-period surface waves in the northern Kanto Basin, Japan. Earth Planets Space 67:33. doi:10.1186/s40623-015-0201-7

Toki K, Irikura K, Kagawa T (1995) Strong motion records in the source area of the Hyogoken-Nambu earthquake, January 17, 1995, Japan. J Nat Disas Sci 16(2):23–30

Toriumi I, Takeuchi Y, Ohba S, Horike M, Inoue Y, Baba K (1990) Underground structure in the Osaka plain by Hokko explosions. Zisin 2 (J Seismol Soc Jpn) 43(3):373–378. doi:10.4294/zisin1948.43.3_373 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Uebayashi H (2003) Extrapolation of irregular subsurface structures using the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio of long-period microtremors. Bull Seimol Soc Am 93(2):570–582. doi:10.1785/0120020137

Viens L, Koketsu K, Miyake H, Sakai S, Nakagawa S (2016) Basin-scale Green’s functions from the ambient seismic field recorded by MeSO-net stations. J Geophys Res 121(4):2507–2520. doi:10.1002/2016JB012796

Wapenaar K, Fokkema J (2006) Green’s function representations for seismic interferometry. Geophysics 71(4):SI33–SI46. doi:10.1190/1.2213955

Wessel P, Smith WHF (1998) New, improved version of generic mapping tools released. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 79:579

Yamanaka H, Chimoto K, Moroi T, Ikeura T, Koketsu K, Sakaue M, Nakai S, Sekiguchi T, Oda Y (2010) Estimation of surface-wave group velocity in the southern Kanto area using seismic interferometric processing of continuous microtremor data. BUTSURI-TANSA (Geophys Explor) 63(5):409–425. doi:10.3124/segj.63.409 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Yoshikawa S, Mitamura M, Nakagawa K, Nagahashi Y, Iwasaki Y, Echigo T, Tsujie K, Kitada N (1998) Lithostratigraphy and tephrostratigraphy of the Tsumori, Otemae and Hama drilling cores in the Osaka Plain, central Japan. J Geol Soc Jpn 104(7):462–476. doi:10.5575/geosoc.104.462 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Yoshimi M (2012) Resolution of the SPAC, CCA, nc-CCA, and V-method for microtremor array survey on deep sedimentary basin—case of the Osaka basin. J Jpn Soc Civil Eng A1 (Struct Eng Earthq Eng) 68(4):I_220–I_226. doi:10.2208/jscejseee.68.I_220 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Zeng C, Zia J, Miller RD, Tsoflias GP (2011) Application of the multiaxial perfectly matched layer (M-PML) to near-surface seismic modeling with Rayleigh waves. Geophysics 76(3):T43–T52. doi:10.1190/1.3560019

Authors’ contributions

KA participated in the temporary observations, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. TI participated in the design of the study and organized the temporary observations. HS participated in the design of the study and prepared the three-dimensional velocity structure model. KS, KM, SA, and TK participated in conducting the temporary observations. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ichiro Matsuo, Naoji Koizumi, and Yasuhiro Umeda for helping to conduct temporary observations in the Osaka basin. In addition, the authors are grateful to the Crisis Management Office of Osaka Prefectural Government, Suita City Fire Department, Matsubara City Office, Kishiwada City Office, Izumi City Office, Sakai City Office, Sakai City Fire Bureau, Osaka Sayama City Office, Yao City Office, Kadoma City Office, Toyonaka City Office, Geo-Research Institute, National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience, and Geological Survey of Japan for cooperation in temporary observations. The temporary observations were conducted as a part of the Comprehensive Research on the Uemachi Fault Zone funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. The Cray XE6 and XC40 supercomputers of the Academic Center for Computing and Media Studies of Kyoto University were used, and Generic Mapping Tools (Wessel and Smith 1998) was used to draw the figures. Careful reviews and comments by Marine Denolle, an anonymous reviewer, and guest editor Francisco J. Sanchez-Sesma were quite helpful for improving the manuscript. This study was partly supported by the Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program of MEXT and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientist (B) 25750146 by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Asano, K., Iwata, T., Sekiguchi, H. et al. Surface wave group velocity in the Osaka sedimentary basin, Japan, estimated using ambient noise cross-correlation functions. Earth Planets Space 69, 108 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0694-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0694-3