Abstract

Background

The presence of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) in livestock animals, especially in pigs, gave rise to concerns of pork being a possible MRSA source to the human population. Monitoring the flow-through of LA-MRSA throughout the meat production chain could be useful. Here, the optimal sampling location for LA-MRSA isolation on pig carcasses was determined.

Findings

In one slaughterhouse, 40 cooled carcass halves from one LA-MRSA-positive herd were sampled on six carcass sites (ham, belly, back, forelimb, sternum and abdominal cavity). The obtained MRSA isolates were characterized using Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis. Without enrichment of the samples, no MRSA was isolated from the carcasses. After enrichment, MRSA was isolated from 19 out of 40 (47.5%) carcasses. The forelimb appeared to be the most contaminated part of the carcass (17/19 carcasses). Three pulsotypes were detected and the predominant pulsotype was also the herd pulsotype that was determined in our previous study.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that the forelimb is a good sampling location for LA-MRSA. For good determination of LA-MRSA on carcasses, enrichment is needed. Only LA-MRSA was isolated. Moreover, the farm strain was isolated from the carcasses, which indicates that transmission from the primary production throughout the slaughterhouse occurred. The results suggest that good hygiene practices in slaughterhouses are important to reduce the transmission of LA-MRSA to the human population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Findings

At present, livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) can be found in the majority of pigs, which could be a potential reservoir for the general human population (Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010). Therefore, a possible exposure route for LA-MRSA is thought to be pork, although low numbers of LA-MRSA have been found indicating a low risk of exposure to the human population (Van Loo et al., 2007; Weese et al., 2010). Pig carcasses can be contaminated with LA-MRSA at the slaughterhouse with farm and/or slaughterhouse strains. For Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) verification purposes and compliance with microbiological criteria for foodstuffs, control samplings for Salmonella occur on a two-weekly basis at the slaughterhouse (European Commission, 2005). To our knowledge, no guidelines are available for the detection of LA-MRSA on pig carcasses. In the present study, different sampling locations for LA-MRSA on a pig carcass were evaluated at the slaughterhouse based on the protocol for Salmonella testing for the compliance with microbiological criteria or foodstuffs (EC, 2005). Moreover, Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed to gain insight into the genetic variety of, and possible sources for, the obtained isolates.

In 2012, sampling was performed in one slaughterhouse, located in the northern part of Belgium. The slaughtered pigs originated from a LA-MRSA-positive farm (Verhegghe et al., 2014). Prior to slaughter, the herd (consisting of 120 animals) was loaded onto a clean truck and transported immediately to the slaughterhouse, where it was slaughtered first that day. Approximately two hours after slaughter, 40 carcasses out of 120 were randomly chosen and one half of each carcass was sampled in the cooling room: 19 right-carcass halves and 21 left-carcass halves. Each carcass half was sampled at six places, being the four locations as described by Ghafir et al. (2005) together with the belly and the back (Figure 1). The outside of the carcass half was sampled at the ham, the belly and the back and the inner part at the inner side of the forelimb, the sternum and the abdominal cavity. From each sampling location, 100 cm2 was swabbed with an envirosponge (3 M DrySponge; BP133ES; Led Techno; St.-Paul, MN, US), premoistened with 7 ml salt-enriched (6.5%; Sodium chloride; 1.06404; Merk, Darmstadt, DE) Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB CM0405; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). All samples were transported and processed immediately upon arrival at the laboratory (two to three hours after the sampling event). Sixty-three ml salt-enriched MHB was added to the sponges; mixed manually for 30 seconds and 100 μl was spread-plated onto a chromogenic MRSA selective medium (Chrom-ID™ MRSA; BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, FR) after which the plates were incubated overnight (18-20 h, 37°C). A ten-fold dilution series of this broth was made in salt-enriched MHB up to dilution 10−3. The dilution series was incubated overnight (37°C for 18-20 h), after which the enrichments were spread-plated and incubated onto Chrom-ID™ MRSA as described above. One suspect colony per plate was purified onto Chrom-ID™ MRSA and Tryptone Soy Agar (TSA;. Pure isolates were stored at −20°C in brain-heart infusion broth (BHI; CM0225; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with glycerol (15% wt/vol; Fisher Scientific, Leicestershire, UK). From each isolate, DNA was extracted according to Strandén et al. (2003) and then stored at −20°C until further use. A MRSA-specific multiplex PCR identified MRSA isolates (Maes et al., 2002). A carcass half was considered MRSA-positive if MRSA was isolated from at least one location. A chi-square test and a Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze the sampling results of the carcass halves and the results of the different locations, respectively. Given that no positive samples were observed on the location “back”, these data were excluded from the analysis. Analysis was performed in SPSS statistics 19 (IBM, Chicago, IL, US) and for all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered significant. A CC398-specific PCR, targeting the restriction-modification system encoding sau1hsdS1, and PFGE using BstZI (Promega, Madison, WI, US) as a restriction enzyme were performed with all obtained isolates as described by Stegger et al. (2011) and Rasschaert et al. (2009), respectively. The obtained PFGE profiles were analyzed with Bionumerics version 6.5 (Applied Maths, St.-Martens-Latem, BE) using the unweighted pair group method using averages (UPGMA) with the Dice coefficient (tolerance 1%, tolerance change 1% and optimization 1%). Pulsotypes were determined based on a delineation level of 97%. Comparison of the pulsotypes with the herd pulsotype was also performed in Bionumerics (Verhegghe et al., 2014).

All MRSA isolates that were found, belonged to CC398, the LA-MRSA complex. LA-MRSA was not detected on the carcass halves after direct plating, indicating that –for this particular case- the level of LA-MRSA contamination on the carcass halves was lower than the detection limit (<7 cfu/cm2). However, it is possible that an underestimation of the LA-MRSA presence occurred. Samples were taken after rapid cooling of the carcasses. S. aureus is able to bind strongly to corneocytes, which could imply that sponge swabbing might not be sufficient to collect all MRSA present and a more destructive method, such as cutting of slices is needed as was reported for Salmonella or E. coli (Ghafir and Daube, 2008; Martinez et al., 2010). Another possibility could be the reduced viability of MRSA after cooling of the carcasses, even though S. aureus is able to persist colder temperatures (Onyango et al., 2012).

After enrichment, LA-MRSA was isolated from 19 out of 40 carcass halves, i.e. 10 right halves and 9 left halves, which was not statistically significant (Chi-square, p = 0.88). From 17 out of 19 halves, LA-MRSA was isolated from only one site (15 times from the forelimb; once from the abdomen and intestine cavity). From two out of 19 halves LA-MRSA was isolated from two sites (forelimb-ham and forelimb-sternum). From 18 halves, MRSA was only detected in the initial enrichment broth, whereas on one half, MRSA was detected up to 10−2 dilution of the enrichment broth. The MRSA prevalence (47.5%) determined in our study, which investigated one herd, was higher than the prevalences observed in two other studies, being 6% and 4% of the carcasses (Beneke et al., 2011 and Hawken et al., 2013, respectively).

Most LA-MRSA isolates were found on the forelimb (17 carcass halves) and once on the ham, belly, abdominal cavity and sternum (Fisher’s exact, P < 0.001). No forelimbs of the carcasses were sampled in the other studies mentioned above, but MRSA was predominantly found on the carcass shoulders, which is in close proximity to the lowest parts of the carcass. In the slaughterhouse, it was noticed that the bottom of the carcass, where the forelimb was located, was visually the dirtiest part of the carcass. In the evisceration room, the lower part of the carcasses came regularly in contact with the side of the evisceration platform. Since MRSA is able to survive the slaughter process and environmental contamination could also occur, the forelimb is an accurate sampling location for MRSA detection. However, the forelimb is not consumed very often in Belgium, which implies that this location is not appropriate to study MRSA transmission to the human population and other locations such as the back or the ham should be considered. However, only one slaughterhouse and carcass halves of only one MRSA-positive herd were sampled during the present study and only one sampling scheme was used. Therefore, to draw firmer conclusions, an additional study including samplings of pig carcasses of different herds at different slaughterhouses and using additional sampling sites is needed to confirm the forelimb as best sampling location for detection of LA-MRSA.

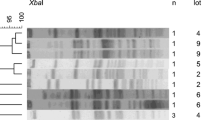

Twenty-two isolates were retrieved from 19 carcass halves and all isolates were identified as MRSA CC398 indicating that -in this case- no human strains had contaminated the carcasses during the slaughter process. Three pulsotypes were found after characterizing the isolates with PFGE. Pulsotype I was retrieved from 18 out of 22 isolates (17 carcass halves) (Figure 2). On one carcass half, pulsotypes I and II were isolated from the forelimb in different dilutions. Pulsotype I was also the only pulsotype found in the herd where the carcass halves originated from (Verhegghe et al., 2014; Figure 2). When a pig is colonized with LA-MRSA, this bacterium can be isolated from the skin and the nares (Broens et al., 2012; Crombé et al., 2012; Szabó et al., 2012). It appears that LA-MRSA is not eliminated from the carcass during the slaughter process. For example, singeing of the carcass might be insufficient to eliminate bacteria from the lower part of the carcass, resulting in MRSA detection on the forelimbs. Besides the herd pulsotype, a minority of isolates with other pulsotypes were found on the carcasses. This indicates that various LA-MRSA strains might be widespread within the slaughterhouse environment, including tracks, lairage and the slaughterline. This could result in cross-contamination of the carcasses, since it has been reported that at the end of a slaughter day MRSA CC398 was widespread in the environment of pig and broiler slaughterhouses (Mulders et al., 2010; Van Cleef et al., 2010; Gilbert et al., 2012). Nevertheless, further research is needed to investigate possible transmission routes for carcasses in a slaughterhouse. In addition, molecular characterization of the obtained isolates would be very valuable to better assess the transmission risk of (LA-)MRSA to the human population through contaminated carcasses and pork.

Comparison of the three obtained slaughterhouse pulsotypes with the herd pulsotype (two out of 43 isolates). A delineation level of 97% (dotted line) was applied to discriminate the different genotypes. Consecutive the dendrogram, pulsotype pattern, pulsotype number and number of isolates belonging to the pulsotype on the total number of typed isolates are shown. For each example, the origin (H: herd, SH: slaughterhouse), pig/carcass number and carcass location is given.

In conclusion, during the present study performed in one slaughterhouse, it was shown that LA-MRSA is regularly present on carcasses. After enrichment, the forelimb appeared a good sampling location to detect LA-MRSA on a carcass half. During the present study, only LA-MRSA was isolated. Moreover, the dominant pulsotype was isolated from the animals of the LA-MRSA-positive herd and from their carcasses, indicating a transmission from the primary production. The retrieval of other pulsotypes on the carcass halves implies that contamination of the carcasses from the slaughterhouse environment may also occur.

Abbreviations

- LA-MRSA:

-

Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- CC:

-

Clonal complex

- ST:

-

Sequence type

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed Field Gel electrophoresis

- UPGMA:

-

Unweighted pair cluster method using averages

References

Beneke B, Klees S, Stührenberg B, Fetsch A, Kraushaar B, Tenhagen B-A (2011) Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a fresh meat pork production chain. J Food Protect 74:126–129

Broens EM, Espinosa-Gongora C, Graat EAM, Vendrig N, Van de wolf PJ, Guardabassi L, Butaye P, de Jong MCM, Van de Giessen AW (2012) Longitudinal field study on transmission of MRSA CC398 within pig herds. BMC Vet Res 8: 58. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-8-58.

Crombé F, Vanderhaeghen W, Dewulf J, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P (2012) Colonization and transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in nursery piglets. Appl Environ Microb 78:1631–1634

European commission (2005) Commision regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for food stuffs (Text with EEA relevance) OJ L338 22.12.2005.

Ghafir Y, China B, Korsak N, Dierick K, Collard JM, Godard C, De Zutter L, Daube G (2005) Belgian surveillance plans to assess changes in Salmonella prevalence in meat at different production stages. J Food Protect 68:2269–2277

Ghafir Y, Daube G (2008) Comparison of swabbing and destructive methods for microbiological pig carcass sampling. Lett Appl Microbiol 47:322–326

Gilbert MJ, Bos MEH, Duim B, Urlings BAP, Heres L, Wagenaar JA, Heederik DJJ (2012) Livestock-associated MRSA ST398 carriage in pig slaughterhouse workers related to quantitative environmental exposure. Occup Environ Med 69:472–478

Hawken P, Weese JS, Friendschip R, Warriner K (2013) Longitudinal study of Clostridium difficile and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with pigs from weaning through to the end of processing. J Food Protect 76:624–630

Maes N, Magdalena J, Rottiers S, De Gheldre Y, Struelens MJ (2002) Evaluation of a triplex PCR assay to discriminate Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci and determine methicillin resistance from blood cultures. J Clin Microb 40:1514–1517

Martinez B, Celda MF, Anastasio B, Garcia I, Lopez-Mendoza MC (2010) Microbiological sampling of carcasses by excision or swabbing with three types of sponge or gauze. J Food Protect 73:81–87

Mulders MN, Haenen APJ, Geenen PL, Vesseur PC, Poldervaart ES, Bosch T, Huijsdens XW, Hengeveld PD, Dam-Deisz WDC, Grant EAM, Mevius D, Voss A, Van de Giessen AW (2010) Prevalence of livestock-associated MRSA in broiler flocks and risk factors for slaughterhouse personnel in The Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 138:743–755

Onyango LA, Dunstan RH, Gottfries J, Von Eiff C, Roberts TK (2012) Effect of low temperature on growth and ultra-structure of Staphylococcus aureus. PlosOne 7:e29031

Rasschaert G, Vanderhaeghen W, Dewaele I, Janez N, Huijsdens X, Butaye P, Heyndrickx M (2009) Comparison of fingerprinting methods for typing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 398. J Clin Microb 47:3313–3322

Stegger M, Lindsay JA, Moodley A, Skov R, Broens EM, Guardabassi L (2011) Rapid PCR detection of Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 398 by targeting the restriction-modification system carrying sau1-hsdS1. J Clin Microb 49:732–734

Strandén A, Frei R, Widmer AF (2003) Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Can PCR replace pulsed-field gel electrophoresis? J Clin Microb 41:3181–3186

Szabó I, Beck B, Friese A, Fetsch A, Tenhagen BA, Roesler U (2012) Colonization kinetics of different methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sequence types in pigs and host susceptibilities. Appl Environ Microb 78:541–548

Van Cleef BAGL, Broens EM, Voss A, Huijsdens XW, Zuchner L, Van Benthem BHB, Kluytmans JAJW, Mulders MN, Van de Giessen AW (2010) High prevalence of nasal MRSA carriage in slaughterhouse workers in contact with live pigs in The Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 138:756–763

Van Loo IHM, Diederen BMW, Savelkoul PHM, Woudenberg JHC, Roosendaal R, Van Belkum A, Toom NLD, Verhulst C, Van Keulen PHJ, Kluytmans JAJW (2007) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in meat products, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1753–1755

Vanderhaeghen W, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P (2010) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food production animals. Epidemiol Infect 138:606–625

Verhegghe M, Pletinckx LJ, Crombé F, Van Weyenberg S, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P, Heyndrickx M, Rasschaert G (2014) Genetic diversity of livestock-associated MRSA isolates obtained from piglets from farrowing until slaughter age on four farrow-to-finish farms. Vet Res 45:89, 10.1186/s13567-014-0089-4

Weese JS, Reid-Smith RJ, Rousseau J, Avery B (2010) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) contamination of retail pork. Can Vet J 51:749–752

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT) project 070596. We thank Pieter Siau for the sampling and laboratory assistance and the slaughterhouse for the collaboration to this study. Special thanks to Miriam Levenson for the English-language editing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

MV carried out the samplings, the sample analyses and drafted the manuscript. FH, PB, LH, MH and GR participated in the design of the study. GR coordinated the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40550-015-0016-0.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Verhegghe, M., Herman, L., Haesebrouck, F. et al. Preliminary evaluation of good sampling locations on a pig carcass for livestock-associated MRSA isolation. FoodContamination 2, 5 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-015-0013-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-015-0013-3