Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has been proposed as diagnostic entity and was added to the section 3 of the DSM 5. Nevertheless, little is known about the long-term course of this disorder and many studies have pointed to the fact that NSSI seems to be volatile over time. We aimed to assemble studies providing longitudinal data about NSSI and furthermore included studies using the definition of deliberate self-harm (DSH) to broaden the epidemiological picture. Using a systematic search strategy, we were able to retrieve 32 studies reporting longitudinal data about NSSI and DSH. We furthermore aimed to describe predictors for the occurrence of NSSI and DSH that were identified in these longitudinal studies. Taken together, there is evidence for an increase in rates of NSSI and DSH in adolescence with a decline in young adulthood. With regards to predictors, rates of depressive symptoms and female gender were often reported as predictor for both NSSI and DSH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has been proposed as a new diagnostic entity in the section 3 (conditions for further study) of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM 5) [1]. The introduction of this new category has been discussed extensively [2–4], with strong arguments both for the implementation (such as i.e. avoiding to falsely label adolescent self-injurers as having borderline personality disorder, and addressing a topic with a high prevalence rate) and for the opposite (i.e. incorrectly calling a behavior “non-suicidal” which is a clear risk factor for suicide attempts). There is still an ongoing debate about how to correctly define self-harming behaviors, with part of the scientific community using the term Deliberate Self Harm (DSH) to describe any self-directed harmful behaviors (indirect or direct), regardless of their suicidal intent [5,6]. In contrast, NSSI defines only directly harmful behaviors without suicidal intent [1].

It remains undisputed that NSSI is a very prevalent phenomenon among adolescents, with lifetime prevalence rates of at least one self-injuring event around 18% in community samples worldwide [7,8]. First studies using the proposed section 3 DSM 5 criteria reported rates between 4% and 7% for adolescent community samples and around 50% for child and adolescent psychiatric samples (for review: see [9]). A recent review also found prevalence rates of NSSI and DSH in adolescents to be comparable [7]. A recent comparison of 12 European countries (using the definition of “direct self-injurious behavior”, which seems close to both a NSSI and a DSH definition), reported a mean prevalence rate of 27.6% in adolescents reaching from 17.1% in Hungary to 38.7% in France [10]. There are only very few studies assessing rates of NSSI in adult community samples. Klonsky reported a 5.9% lifetime prevalence rate of NSSI using a random digit dialing sample from the US [11]. This inconsistency of high lifetime prevalence rates in adolescence and rather low lifetime prevalence rates in adults [8] requires further exploration. One explanation might be a re-attribution in adulthood, considering adolescent NSSI as being “nothing important to report”, which would lead to underestimation in studies about lifetime NSSI rates in adults. Furthermore, there might be a memory bias of adults not remembering how frequently they had engaged in NSSI in adolescence. Alternatively, it might be possible that NSSI has increased in recent years, however, no indication for a rise of prevalence rates was found in the two systematic reviews of the literature [7,8]. Given that both NSSI and DSH are highly prevalent in community sample and emerge in adolescence, research about predictors of these behaviors are highly relevant as they could inform preventive interventions. As predictors can be best identified through longitudinal research, studies focusing on a longitudinal assessment have the potential to inform researchers and policy makers.

Given this questions, it seems worthwhile to pay a closer look to the longitudinal development of NSSI and DSH. We therefore performed a systematic literature review to include every study that assessed NSSI and DSH longitudinally. Aims of this review were to (1) assess the stability of prevalence rates of NSSI and DSH over time. Further, (2) to compare 12-month incidence rates of NSSI and DSH in adolescents and adults and (3) to identify predictors for NSSI and DSH that have been reported constantly in longitudinal research.

Review

We performed a systematic review of the literature using Medline and OVID. As a search strategy we used the terms “NSSI”, “DSH”, “self-harm”, “self-injury”, “deliberate self-harm”, “nonsuicidal self-injury” in conjunction with “longitudinal” or “course”. Only studies written in English or German providing longitudinal data about NSSI or DSH and published before the 1st of August 2014 were included. Only studies measuring NSSI/DSH at - at least - two consecutive points in the same individuals were included. We excluded studies focusing on self-harm in populations with pervasive developmental disorders or mental retardation or studies providing longitudinal data about predictors of NSSI or DSH but just measuring NSSI/DSH at one point in time (see Figure 1). This led to the inclusion of 43 studies (see Tables 1 and 2).

Results

Of the 32 studies selected, 22 (69%) represented studies on NSSI, whereas ten studies (31%) used a definition of DSH (see Tables 1 and 2). Combining both, 24 (75%) of the studies presented data from community samples and nine studies (25%) reported data from clinical samples or from clinical studies (including the study by Prinstein et al. [12], presenting data both from a community and a clinical sample; for details see Tables 1 and 2). Twenty-five (78%) of all studies reported on participants who were in their adolescence during baseline.

On average, duration of follow-up was 19.53 months (SD: 18.76) in studies concerning NSSI and 67.4 months (SD: 66.7) in studies concerning DSH. Although the huge difference was driven by the studies by Moran et al., [13], and Wedig et al., [14] who provided a follow-up for around 15 and 16 years respectively concerning DSH, exclusion of these outliers still yielded a result of a longer follow-up period in DSH studies (M = 38.5 months, SD = 30.4). Number of participants encompassed N = 969,197 in studies on NSSI (mean number of participants: N = 44,054; SD = 199,341). As this number was mainly due to the large number of participants from a registry study [15], calculations after exclusion of this study showed smaller numbers (N = 32,748; mean number of participants: N = 1,559; SD = 3,025). Overall, 20,496 individuals participated in longitudinal studies of DSH (mean number: N = 2,049, SD = 1,688).

Developmental course of NSSI and DSH

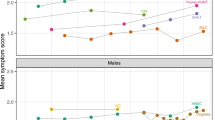

It was possible to retrieve data about decline or increase of rates from 17 studies on NSSI and five studies on DSH. There was a decrease in rates of NSSI during the follow-up in 12 ([12]: both study populations; [16–25]) and an increase in five ([26–30]) of these 17 studies on NSSI. The course of NSSI throughout adolescence is shown in Figure 2. However, only seven studies provided data on community samples of adolescents measuring the same time-frame of prevalence (i.e. 6-months prevalence) of NSSI at all time-points.

Studies on prevalence of NSSI in adolescent community samples. Only studies giving information about mean age of participants, and which used the same prevalence measures for each time-point, were included. For individual prevalence time-frames (i.e. 3-months, 6 months, etc.) of each study see Table 1.

Interestingly, five out of the six studies showing an increase of rates of NSSI, were performed in younger adolescents. A decrease in NSSI was mainly found in older adolescents and adults (see Figure 2 and Table 1).

An incidence rate of NSSI within a 12 month time frame was provided in five studies of NSSI in community samples of adolescents and young adults (mean incidence rate: 4.32%, SD: 1.08). In studies using a DSH definition, a decline was described in four ([13,14,31,32], and an increase in one [33] of the five eligible studies (see Table 2).

Predictors of NSSI and DSH

Analyzing the predictors of NSSI and DSH, only longitudinal predictors (existing at or before baseline) for NSSI during or at follow-up were included. A similar pattern could be found for NSSI and DSH. For NSSI, the predictor cited most often was previous NSSI, followed by depression, female gender, suicidality and psychological distress (see Table 3).

For DSH, higher scores of depression were described as predictor in the majority of studies, followed by female gender, lower self-esteem and alcohol/ drug use. Past behavior (previous DSH) as predictor of future DSH was described in two studies. Overall, numerous predictors overlapped in studies of NSSI and DSH.

Conclusion

Performing a systematic review of the literature, we were able to retrieve 32 studies, which assessed either NSSI or DSH longitudinally. Overall, both NSSI and DSH showed high volatility between assessment points with some studies reporting an increase, and some reporting a decrease of self-harming behaviors over time. Even within studies, there were high rates of discontinuation vs. new initiation of self-harming behaviors. A pattern emerged in studies of NSSI with studies being performed in young adolescents showing an upward trend in rates of NSSI, whereas studies in older adolescents or young adults showed a decrease in rates.

This could point to a natural course of NSSI with an increase in young adolescence and a decrease in late adolescence/young adulthood. The only study, which covered the whole time range from adolescence to adulthood, so far, is that of Moran et al. [13]. Although the study focused on self-harm, thus also including suicidal behavior, the authors described a decrease in self cutting/burning behavior from adolescence to adulthood. Since this study is the most long-lasting and one of the largest studies in this field of research, it seems possible to suggest that both NSSI and DSH peak in adolescence at around 15 to 17 years and then remit in young to middle adulthood. Describing NSSI as a behavior that seems to change quickly, it makes sense to restrict possible diagnostic criteria of NSSI disorder to a short time span. As proposed in section three of the DSM 5 [1], there should be repeated incidents of NSSI within a year to define the behavior. NSSI that has remitted for longer than a year or is not repetitive in its nature should not be classified as a disorder.

With regards to a developmental course, it would be interesting to follow up a broad range of risk behaviors over time. NSSI has been described as strong risk factor for later suicidality repeatedly (for review see [34]), with suicide attempts also increasing in adolescence for the first time [35]. Future studies therefore need to shed light on possible changes in behavior, i.e. NSSI possibly diminishing over time but being substituted by suicidal behavior or other risk seeking behavior such as illicit drug use.

Looking into predictors reported from longitudinal research, there seems to be an overlap between studies focusing on NSSI and those focusing on DSH. Namely, among the predictors found in several studies on DSH and NSSI, past self-harming behavior seems to be one of the strongest predictors for future behaviors. In addition, depressive symptomatology as well as female gender were reported in multiple studies. Knowledge about predictors could aid the development of preventive interventions, which could focus i.e. on the detection of depressive symptoms and need to be tailored for gender.

In addition to prevention programs, early interventions programs need to be established, focusing on those already injuring themselves and trying to stop the self-harming behavior which in itself is a predictor of future behavior. Several reviews have also identified social and family factors contributing to NSSI and DSH, suggesting preventive interventions should also address this topic (such as by integrating strategies against bullying).

However, due to the vast heterogeneity of the studies included in this review, general comments about the longitudinal course and predictors of NSSI/DSH are not easy to come up with. First, this is due to the different definitions of self-injurious behaviors used across studies. Further, assessment tools ranged from one question (i.e. “have you ever intentionally harmed yourself”) to extensive interviews. Also, a number of studies did not assess self-injury homogeneously at all time-points (i.e. lifetime-NSSI at baseline and 3-months prevalence at follow-up), which made interpretation difficult at times. Moreover, follow-up periods were very heterogeneous, ranging from several months to 16 years. Therefore, a standardized definition of self-injurious behaviors and an establishment of evaluated tools for measuring NSSI seems to be well needed.

Limitations: This review presents a wide range of studies with different aims, therefore description of predictors and according to the numbers of studies in which the predictors were described is in no way meant as weighing predictors against each other. As some studies have looked at special aspects of NSSI or DSH, the range of predictors that were examined was restricted. Nevertheless, there seems to be a pattern of certain predictors that were described repeatedly and consistently throughout studies, which seems to be an interesting finding. Further, only studies in English or German language were included. This was due to language skills of the authors and limited resources, which did not allow for translation of articles in all relevant languages.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Wilkinson P, Goodyer I. Non-suicidal self-injury. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:103–8.

Plener PL, Kapusta ND, Kölch MG, Kaess M, Brunner R. Nicht-suizidale Selbstverletzung als eigenständige Diagnose: Implikationen des DSM-5 Vorschlages für Forschung und Klinik selbstverletzenden Verhaltens bei Jugendlichen. Zeitschrift Kinder Jugendpsychiatrie Psychotherapie. 2012;40:113–20.

De Leo D. DSM-V and the future of suicidoloy. Crisis. 2011;32:233–9.

Madge N, Hawton K, McMahon EM, Corcoran P, De Leo D, de Wilde EJ, et al. Psychological characteristics, stressful life events and deliberate self-harm: findings from the child and adolescent self-harm in Europe (CASE) study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:499–508.

Kapur N, Cooper J, O'Connor RC, Hawton K. Non-suicidal self-injury v. attempted suicide: new diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:326–8.

Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2012;6:10.

Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:273–303.

Plener PL, Kapusta ND, Brunner R, Kaess M: Nicht-suizidales selbstverletzendes Verhalten (NSSV) und Suizidale Verhaltensstörung (SVS) im DSM-5. Zeitschrift Kinder Jugendpsychiatrie Psychotherapie, in press.

Brunner R, Kaess M, Parzer P, Fischer G, Carli V, Hoven CW, et al. Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:337–48.

Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1981–6.

Prinstein MJ, Heilbron N, Guerry JD, Franklin JC, Rancourt D, Simon V, et al. Peer influence and nonsuicidal self injury: longitudinal results in community and clinically-referred adolescent samples. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:669–82.

Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Olsson C, Borschmann R, Carlin JB, et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2012;379:236–43.

Wedig MM, Silverman MH, Frankenburg FR, Reich B, Fitzmaurice G, Zanarini MC. Predictors of suicide attempts in patients with borderline personality disorder over 16 years of prospective follow-up. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2395–404.

Modén B, Ohlsson H, Merlo J, Rosvall M. Risk factors for diagnosed intention self-injury: a total population-based study. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;24:286–91.

You J, Leung F, Fu K. Exploring the reciprocal relations between nonsuicidal self-injury, negative emotions and relationship problems in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal cross-Lag study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:829–36.

Franklin JC, Puzia ME, Lee KM, Prinstein MJ. Low implicit and explicit aversion toward self-cutting stimuli longitudinally predict nonsuicidal self-injury. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:463–9.

Wan YH, Xu SJ, Chen J, Hu CL, Tao FB: Longitudinal effects of psychological symptoms on non-suicidal self-injury: a difference between adolescents and young adults in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014, doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0917-x.

Hamza CA, Willoughby T. A longitudinal person-centered examination of nonsuicidal self-injury among university students. J Youth Adolescence. 2014;43:671–85.

You J, Lin MP, Leung F: A Longitudinal Moderated Mediation Model of Nonsuicidal Self-injury among Adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2014, doi:10:1007/s10802-014-9901-x.

Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury: a I-year longitudinal study in young adults. Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. 2011;42:751–62.

Barrocas AL, Giletta M, Hankin BL, Prinstein MJ, Abela JRZ: Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescence: Longitudinal Course, Trajectories, and Intrapersonal Predictors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2014, doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9895-4.

Guerry JD, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal prediction of adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: examination of cognitive vulnerability-stress model. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39:77–89.

McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ralevski E, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, et al. Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: toward a hybrid model of axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:883–9.

Tuisku V, Kiviruusu O, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Strandholm T, Marttunen M. Depressed adolescents as young adults – predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:313–219.

Hasking P, Andrews T, Martin G. The role of exposure to self-injury among peers in predicting later self-injury. J Youth Adolescence. 2013;42:1543–56.

Marshall SK, Tilton-Weaver LC, Stattin H. Non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms during middle adolescence: a longitudinal analysis. J Youth Adolescence. 2013;42:1234–42.

Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. Change in emotion regulation strategy Use and its impact on adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: a three-year longitudinal analysis using latent growth modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:487–98.

Hankin BL, Abela JRZ. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: prospective rates and risk factors in a 2 ½ year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:65–70.

Baetens I, Claes L, Onghena P, Grietens H, Van Leeuwen K, Peters C, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: a longitudinal study of the relationship between NSSI, psychological distress and perceived parenting. J Adolesc. 2014;37:817–26.

O’Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Hawton K. Predicting deliberate self-harm in adolescents: a Six month prospective study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;39:364–75.

Rossow I, Norström T. Heavy episode drinking and deliberate self-harm in young people: a longitudinal cohort study. Addiction. 2014;109:930–6.

Larsson B, Sund AM. Prevalence, course, incidence, and 1-year prediction of deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts in early Norwegian school adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:152–64.

Andover MS, Morris BW, Wren A, Bruzzese ME. The co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and attempted suicide among adolescents: distinguishing risk factors and psychosocial correlates. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2012;6:11.

Nock MK, Borges G, Bromets EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–54.

Tatnell R, Kelada L, Hasking P, Martin G. Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:885–96.

Martin G, Thomas H, Andrews T, Hasking P, Scott JG: Psychotic experiences and psychological distress predict contemporaneous and future non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in a sample of Australian school-based adolescents. Psychological Medicine 2014, doi:10.1017/S00332917114001615/1-9.

Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Baral Abrams G, Barreira P, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:486–92.

Rosenbaum Asarnow J, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2011;8:772–81.

Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the adolescent depression antidepressants and psychotherapy trial (ADAPT). Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501.

Lundh LG, Wangby-Lundh M, Paaske M, Ingesson S, Bjärehed J. Depressive symptoms and deliberate self-harm in an community sample of adolescents: a prospective study. Depression Research and Treatment. 2011;935871:1–11.

Bjärehed J, Wangby-Lundh M, Lundh LG. Nonsuicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents: subgroups, stability, and assocations with psychological difficulties. J Res Adolesc. 2012;22:678–93.

Stallard P, Spears M, Montgomery AA, Phillips R, Sayal K. Self-harm in young adolescents (12–16 years): onset and short-term continuation in a community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:1–14.

Wichstrom L. Predictors of non-suicidal self-injury versus attempted suicide: similar or different? Arch Suicide Res. 2009;13:105–22.

Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, Cooper J, Steeg S, Ness J, et al. Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:1212–9.

Sinclair J, Hawton K, Gray A. Six year follow-up of a clinical sample of self-harm patients. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:247–52.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the helpful comments of the reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

PLP declares no competing interests. He is PI in a study for Lundbeck. He got research grants from the BMBF (German Ministries for Research and Education) and the BfArM (German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical devices). He received travel grants from the DFG, DAAD and IACAPAP. He isn’t stockholder or share-holder in the pharmaceutical industry. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PLP designed the review strategy, carried out the systematic review and drafted the manuscript. TS retrieved the literature and analyzed the provided material. LMM analyzed and summarized the studies. RCG participated in designing and coordinating the review and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Plener, P.L., Schumacher, T.S., Munz, L.M. et al. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature. bord personal disord emot dysregul 2, 2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0024-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0024-3