Abstract

Gliomas are the most common central nervous tumors in children and adolescents. However, spinal cord low-grade gliomas (sLGGs) are rare, with scarce information on tumor genomics and epigenomics. To define the molecular landscape of sLGGs, we integrated clinical data, histology, and multi-level genetic and epigenetic analyses on a consecutive cohort of 26 pediatric patients. Driver molecular alteration was found in 92% of patients (24/26). A novel variant of KIAA1549:BRAF fusion (ex10:ex9) was identified using RNA-seq in four cases. Importantly, only one-third of oncogenic drivers could be revealed using standard diagnostic methods, and two-thirds of pediatric patients with sLGGs required extensive molecular examination. The majority (23/24) of detected alterations were potentially druggable targets. Four patients in our cohort received targeted therapy with MEK or NTRK inhibitors. Three of those exhibited clinical improvement (two with trametinib, one with larotrectinib), and two patients achieved partial response. Methylation profiling was implemented to further refine the diagnosis and revealed intertumoral heterogeneity in sLGGs. Although 55% of tumors clustered with pilocytic astrocytoma, other rare entities were identified in this patient population. In particular, diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumors (n = 3) and high-grade astrocytoma with piloid features (n = 1) and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (n = 1) were present. A proportion of tumors (14%) had no match with the current version of the classifier. Complex molecular genetic sLGGs characterization was invaluable to refine diagnosis, which has proven to be essential in such a rare tumor entity. Moreover, identifying a high proportion of drugable targets in sLGGs opened an opportunity for new treatment modalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of CNS tumors are located intracranially, and only 5% occur in the spinal cord [1]. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors have a glial origin and are biologically low-grade in 95%. Similarly, as in brain low-grade gliomas (LGGs), spinal cord (= intramedullary) low-grade gliomas in children (sLGGs) show a chronic course of the disease affecting the quality of life while the overall survival remains excellent [2]. Treatment of choice is maximal safe surgical resection under intraoperative monitoring which must not endanger neurological function as chemotherapy can stabilize the progression of the disease in 40–50% [3, 4].

The urge is to predict the risk of progression and search for novel, effective treatment approaches. Molecular data are seldom, suggesting that the most prevalent alteration is KIAA1549:BRAF fusion [5]. Due to the rarity of the disease, genomic data are scarce or incomplete, and the use of targeted therapy in sLGGs was not demonstrated yet. Therefore, an institutional integrated clinical and comprehensive genetic study was conducted to reveal sLGG-associated molecular alterations and their therapeutic implications, assess intertumoral heterogeneity using methylation profiling, and demonstrate the effect of targeted therapy in this group of patients.

Methods

Patient cohort and clinical follow-up

Tumor samples and clinical data from patients with sLGGs diagnosed and treated at our center from 2000 to 2021 were retrieved for survival, radiologic data, and molecular evaluation. Patients were followed on an out-patient or in-patient basis with regular MRI imaging. All clinical data were collected retrospectively. The last patient was enrolled on 02/11/2020, and the disease status for all patients was updated on 01/07/2021. The institutional review board approved the study, and all patients obtained informed consent as per our routine procedure.

Volumetric analysis

Volumetric analysis was implemented to measure tumor response to the targeted therapy. Lesions' volumes were estimated with open-source software 3D Slicer (version 4.10.2) using basic modules (Segment Editor, Segment Statistics) [6]. MRI sequences with the best spatial and contrast resolution were selected from available examinations for lesion volume evaluation.

DNA and RNA extraction

The nucleic acids were extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue block using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Quiagen, Germany) for genomic DNA and using high pure RNA paraffin kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for total RNA. In the case of fresh frozen sections, extraction of genomic DNA and total RNA was manufactured using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, Merelbeke, Belgium). Neuropathologists selected the most representative tissue blocks containing the maximum percentage of tumor tissue before isolation of nucleic acid.

cDNA synthesis and conventional RT-PCR

cDNA was prepared from RNA (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was subjected to conventional RT-PCR amplification with primers specific for common KIAA1549:BRAF variants(ex16:ex9, ex15:ex9, ex16:ex11) as previously described [7].

Sanger sequencing

PCR and Sanger sequencing were conducted to examine hotspot mutations at codons 27 and 34 of H3F3A, codon 600 of BRAF ex15, codons 546 and 656 of FGFR1 ex12, and codon of FGFR1 ex14 using previously described primer pairs. Amplification was performed using 2 × PCRBIO HS Taq Mix Red (PCR Biosystems Ltd., London, UK). The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel and were recovered using the Gel DNA Fragments Extraction Kit (Geneaid, Taiwan). Sanger sequencing was performed using Big Dye Terminator v 3.1 chemistry (LifeTechnologies) and an ABI PRISM 3130 genetic analyzer Applied Biosystems. Results were analyzed using Chromaslite 2.01 (Technelysium, PtyLtd, Brisbane, Australia).

MLPA

SALSA® MLPA® probemix P370 can be used to detect genomic duplications leading to the KIAA1549:BRAF, SRGAP3:RAF1, and FGFR1:TACC1 fusion genes and for detection of copy number aberrations in the BRAF, CDKN2A/2B, FGFR1, MYB, and MYBL1 genes. Furthermore, this probemix contains five specific probes detecting the BRAF p.V600E & four predominant IDH1 p.R132H and p.R132C and IDH2 p.R172M and p.R172K point mutations, which will only generate a signal when the mutation is present. MLPA was performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Data were analyzed using Coffalyser Software (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

RNA panel sequencing

Based on the quality of preserved nucleic acid in the samples, we were using one of Archer® FusionPlex® (Archer DX, Boulder, Colorado) commercially available panels—either Lung kit or Oncology Research kit. Despite different nucleic acid quality requirements resulting from the different number of analyzed genes, both panels are used for fusion and SNV identification with the advantage of identifying the fusion even with an unknown partner. Archer® FusionPlex® also offers robust performance even for FFPE samples. RNA extraction, library preparation, and parallel sequencing were performed as per the manufacturer's recommendation. Anchored Multiplex polymerase chain reaction amplicons were sequenced on Illumina MiSeq, and the data were analyzed using the Archer and Arriba [8] (https://github.com/suhrig/arriba/) softwares. RT-PCR was performed to validate the fusion transcript identified by RNA sequencing (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Methylation profiling

DNA methylation was performed using the Infinium Methylation EPICBeadChip Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). A total of 250 ng of DNA from fresh frozen tumor tissue was treated with bisulfite conversion using the ZymoResearch EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA, USA). In the case of FFPE samples, DNA restoration was performed as per the manufacturer's instructions (Infinium FFPE DNA Restoration kit, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). According to the manufacturer's explicit specifications, the Infinium HD Methylation Assay was performed at the laboratories of the Department of Pediatric Haematology and Oncology, Second Faculty of Medicine in Prague. The methylation class was established using web-based analysis via https://www.molecularneuropathology.org/ using publically available v11b4 and v12.5 versions of brain classifier. To compare spinal cord glioma samples with the DKFZ reference cohort, t-SNE analysis was performed with 10,000 most differentially methylated probes using Rtsne package v.0.13 as previously described [9].

Statistical analysis

Progression-free survival and overall survival were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and p-values reported using the log-rank test in an open-source R statistical environment (v4.1.2), using R packages survival (v2.41–3), and ggplot2 (v2.2.1).

Results

Patient selection

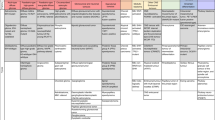

During the study period, 42 pediatric patients with spinal cord tumors were diagnosed, excluding non-biopsied patients with known Neurofibromatosis type 2. Diagnosis of sLGGs was made in 23 patients; 12 patients were diagnosed with ependymoma, and four patients with ATRT or other entity (Fig. 1a). Retrospective evaluation of the spinal cord tumor cohort revealed discordance between histology and the clinical course of the disease in three patients. Additional testing done in 2 ependymoma patients with atypical clinical course revealed rather glial tumors with ependymal features. Furthermore, one long-term surviving patient with an inoperable tumor initially described as anaplastic astrocytoma showed rather low-grade biology of the tumor with multiple progressions over many years of follow-up. In this particular patient, molecular studies revealed NTRK2 fusion and confirmed a glial origin of the tumors with low-grade behavior. Therefore, these three patients were added to the sLGGs group in this article to a total number of 26 patients (Additional file 2: Table S2; sLGG_01—sLGG_26), representing 7% of all institutional pediatric LGGs (total number = 350). Median age at diagnosis for the sLGGs group was 4.55 years (range from 1.15 to 17.54 years). Histologically, the sLGGs group comprised predominantly of pilocytic astrocytoma, diffuse astrocytoma, and ganglioglioma.

a Overview of the total number of 42 spinal cord tumors diagnosed within 2000–2021. b Pie of pie demonstrates three molecular alteration groups in sLGGs; tumors driven with canonical BRAF fusions, non-canonical BRAF fusions, and non-BRAF alterations. c Oncoplot summarizes the relation of demographic (sex, age), clinical (progression, survival), and molecular-pathology data (histology, driver alteration, CDKN2A status), d Comparison of the molecular alterations, anatomical location, and extent of the tumors. The position of vertical lines shows the anatomical location of the tumor and the length of vertical lines outlines the levels of the spinal cord affected by each tumor sample. Molecular subtypes are shown in colors. On the left side are displayed common KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (pink) in contrast with the right side where are rare KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (yellow), a novel type of KIAA1549:BRAF fusion (red), non-KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (green) and non-BRAF alterations (blue)

Comprehensive genomic analysis uncovered a novel and rare alterations within the MAPK pathway

Comprehensive genetic analysis consisting of Sanger sequencing, MLPA, and RNA sequencing was employed to determine the genetic landscape of pediatric LGGs. Oncogenic driver alterations were detected in 93% (n = 24) of patients; no alterations were detected in two patients where analysis failed due to insufficient tissue quality. Alterations found across sLGGs could be classified into two groups (Fig. 1b: 1) BRAF alteration consisting of KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (75%) with the high occurrence of rare and novel fusion variants, and non-KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (8%), 2) non-BRAF alterations (17%). Surprisingly, no case harboring BRAFV600E or H3F3A/HIST1H3B mutation was identified. We also evaluated the presence of the secondary alterations and found two cases of CDKN2A homozygous deletion in non-BRAF tumors. (Fig. 1c) Furthermore, pathogenic MET and EGFR variants were detected in two KIAA1549:BRAF cases.

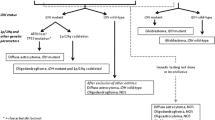

A novel variant of KIAA1549:BRAF fusion (ex10:ex9) was identified using RNA sequencing in four cases (Fig. 2a). Rare types of KIAA1549:BRAF fusions (ex13:ex9, ex13:ex11, ex16:ex11, ex15:ex11) were identified in further 21% sLGG patients. Non-canonical BRAF fusions were detected in two patients; accounting for BCAS1:BRAF and GNAI1:BRAF. Two independent methods verified those rare and novel BRAF fusions using RT-PCR with specific primers and chromosome 7q34 duplication using MLPA.

a Novel KIAA1549:BRAF fusion variant—ex9:ex10. The diagram shows an in-frame fusion gene incorporating the kinase domain of BRAF oncogene. b MRI images demonstrate similarities in the anatomical location of sLGGs in patients with detected novel KIAA1549:BRAF ex9:ex10 fusion variant. Tumors are delineated with green line

Anatomical distribution of the genetic alterations (Fig. 1d) interestingly showed KIAA1549:BRAF ex10:ex9-positive tumors located in the upper half of the spinal cord with partial medulla oblongata involvement in two cases (two cases in the cervical spine (C1–C7), one case in the cervical and upper thoracic spine (C2–T2), and one in the upper thoracic spine (T2–T7) (Fig. 2b). To evaluate the frequency of the KIAA1549:BRAF ex10:ex9 fusion variant, the cohort was expanded using 205 institutional cases of intracranial pediatric LGGs of various locations with known molecular drivers (Additional file 3: Fig. S1). Among more than 50 cases with detectable KIAA1549:BRAF, no case harbored an ex10:ex9 variant suggesting exclusive occurrence in the spinal cord.

Non-BRAF alterations were detected in four tumor samples consisting of CLIP2:NTRK2, KANK1:NTRK2, RAF1:QKI, and KRAS Q61H. The young age of three years and under at diagnosis characterized this group of patients. This group's histological appearance was not typical for LGG, and molecular testing helped refine the diagnosis. CLIP2:NTRK2 case was diagnosed as an anaplastic astrocytoma grade 3. Despite HGG histology, the presence of CDKN2A homozygous deletion, and multiple progressions, the patient was alive 15 years from the time of diagnosis. Pathologists reported two cases (KANK1:NTRK2 and RAF1:QKI) as ependymomas, but these tumors were reclassified as low-grade glioma due to the clinical course, underlying molecular alteration, and methylation profile. Based on the molecular profile, the case with KANK1:NTRK2 that also harbored CDKN2A homozygous deletion was treated with a radiation-sparing approach using chemotherapy only as first-line therapy. Patient with sLGG harboring RAF1:QKI underwent subtotal resection followed by careful observation. KRAS Q61H mutated case had histology of low-grade glioneuronal tumor (LGNT), and the patient was observed only after partial resection.

Methylation profiling revealed significant intertumoral heterogeneity among sLGGs

The current version (v12.5) of the Heidelberg methylation classifier does not provide any methylation class specific for spinal cord gliomas in contrast to spinal cord ependymomas. Therefore, we performed methylation profiling to evaluate how would sLGGs be classified based on the epigenetic features and to discern intertumoral heterogeneity. The analysis was performed using publically available Heidelberg classifier v12.5. Out of 22 patients (91.6%) with sufficient tissue available, 12 tumors (55%) were predicted as pilocytic astrocytoma, subclass posterior fossa (PA-PF) despite variable calibrated scores (calibrated scores (CS) 0.35–0.99). Three tumors (14%) with 1p deletion matched with diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor (DLGNT), methylation class 1 (DLGNT – MC1) (two CS 0.99, one CS 0.25). One anaplastic astrocytoma with CLIP2:NTRK2 fusion was classified as anaplastic pilocytic astrocytoma (CS 0.62), currently also known as high-grade astrocytoma with piloid features (HGAP). The other NTRK2 fused glioma (KANK1:NTRK2), originally diagnosed as ependymoma, was classified as pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) (CS 0.90). One case (QKI:RAF1) was clustered with a subtype A of glioneuronal tumors (CS 0.99). One case (KIAA1549:BRAF ex10:ex9) was classified as desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma / desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma (CS 0.59). The remaining three tumors (14%) matched with control tissue most probably due to low tumor tissue content. Moreover, t-SNE analysis using a previously published reference cohort was performed to further refine the methylation class prediction. As classified by v12.5, significant proportion of the samples clustered nearby PA-PF cluster. They seemed to be forming a separate cluster suggesting a possible distinction from posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytoma. Remaining samples clustered with DLGNT, GNT, PXA, and other clusters as predicted with the classifier (Fig. 3).

T-SNE plot demonstrates the intertumoral heterogeneity among sLGGs. Prague samples (large red dots) are displayed among cases relevant methylation classes. This figure displays a close-up of the t-SNE with the whole reference cohort (see Additional file 4: Fig S2)

Clinical outcome and exploitation of molecular targets

At a median follow-up of 6.96 years (IQR: 3.42–12.22), 5-year progression-free survival was 67.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 50.8–89.1%). Overall survival rate at 5 years was 95.2% (95% [CI], 86.6–100.0%) (Fig. 4a). Infants of three years and younger fared significantly worse compared to those older than three with 5-year PFS 37.5% (CI 95%, 16.2–86.8%) and 85.9% (CI 95%, 69.5–100%), respectively (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b) Three patients died of the disease 15, 10, and two years after diagnosis respectively due to the progressive disease, regardless of the histological grade or molecular alteration (one with CLIP2:NTRK2, one without known driver alteration, and one with KIAA1549:BRAF ex10:ex9 variant).

Based on molecularly identified targets, four patients received targeted therapy using MAPK pathway inhibitors. Three patients with KIAA1549:BRAF fusion were treated with MEK-inhibitor trametinib. According to the volumetric measurements, one of the patients (sLGG_15) responded with stable disease, and two patients (sLGG_06 and sLGG_07) exhibited partial responses (reduction of 51% and 61%) that were achieved after 5 and 8 months, respectively. Patient (sLGG_22) with CLIP2:NTRK2 fusion was treated with TRK inhibitor larotrectinib with quickly induced volume reduction, not meeting partial response (40%), detectable on magnetic resonance 54 days after the therapy initiation (Fig. 5). The radiological volume reduction was accompanied by significant clinical improvement with no remarkable drug-related toxicity. Unfortunately, tumor progression accompanied by clinical decline was detected after 22 months of targeted therapy. After another five months, the patient died due to the tumor progression to the brainstem. DNA sequencing from autopsy material did not reveal any point mutations in the NTRK1/2/3 kinase domain; thus, the mechanism of acquired resistance remained unknown [10].

Radiological response to the targeted therapies. The white line (a.1) indicates tumor volume before initiation of NTRK inhibitor in patients sLGG_22, and (a.2) shows a 40% tumor volume reduction after 54 days of therapy. Likewise, the white line (b.1) shows tumor volume before initiation of MEK inhibitor in patient sLGG_07, and (b.2) shows a 61% tumor volume reduction after eight months of therapy

Discussion

Here we present a study with comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis in a 20-year retrospective single institutional non-selected cohort of 26 consecutive sLGG patients in the context of clinical course, including quantitative imaging analysis and employment of novel treatment modalities. New findings regarding significant epigenetic heterogeneity were for the first time reported in pediatric sLGG population. Furthermore, identification of fusion landscape including novel fusion variants highlighted the impact of our data on diagnostics and new therapeutic opportunities.

We confirmed that the majority of pediatric sLGGs harbored KIAA1549:BRAF fusions, but unlike intracranial location, rare and novel variants were predominantly present. In particular, the novel KIAA1549:BRAF ex10:ex9 was uncovered in our study. Importantly, this fusion variant was not found in any of our institutional pediatric intracranial LGGs cases, making this variant specific for the spinal cord compartment. Moreover, to our knowledge, this fusion variant has not been reported yet in the literature. As reported in other KIAA1549:BRAF variants, the variant ex10:ex9 also lacked the autoinhibitory domain and caused MAPK activation in the same manner [11, 12] (Fig. 2a).

Non-BRAF fusions were detected in children younger than three years and consisted of tumors with NTRK2 and RAF1 fusions and KRAS mutation. The clinical course of the disease in non-BRAF fusion patients tended to progress requiring multiple treatment modalities. Furthermore, two patients with non-canonical BRAF fusions (BCAS1:BRAF, GNAI1:BRAF) were revealed and confirmed that non-canonical BRAF fusions could occur in the sLGGs. Interestingly, there was no spinal cord glioblastoma characterized by histone H3F3A mutation in the presented cohort of spinal cord tumors [13]. No BRAF V600E mutation was detected in our cohort, probably due to a limited number of patients and a low prevalence of BRAF V600E mutation in sLGG [5, 14].

Survival in regards to 5-year PFS (67.3%) and OS (95.2%) was comparable with more extensive series with predominantly intracranial pediatric LGGs or sLGGs [5, 14]. Importantly, significantly worse PFS in younger children compared to the older ones stood out in the presented cohort. The extent of resection did not influence our PFS data as only two patients had their sLGGs completely removed. Therefore, the poorer outcome of younger children might have been related to the presence of non-BRAF alterations in combination with more frequent occurrence of cases with atypical histology. Our observation of a poorer prognosis was consistent with previously published clinical trials where young children fared significantly worse [15, 16]. Frequent non-BRAF fusions in younger children with sLGGs and histology not typical for true pediatric LGGs resembled cases of infant hemispheric gliomas, [17, 18] underlying the necessity of multi-layer diagnosis integrating histopathology and molecular genetics analysis. Some of our very young children with sLGGs were diagnosed with "ependymoma-like" histology, and further molecular investigation helped to refine the diagnosis.

Previously published studies evaluated the genomic landscape of spinal cord gliomas. More extensive series usually presented limited information on molecular alterations restricted to data from molecular biology methods such as FISH, NanoString platform, or RT-PCR [5], most probably due to poor tumor tissue availability. Grob et al. showed that 42% of sLGGs tested positive for KIAA1549:BRAF fusion [5]. It is essential to underline that the most frequent alterations in our cohort were rare and novel KIAA1549:BRAF fusion variants. The mechanism of BRAF activation remains the same, but commonly used diagnostic methods (RT-PCR with specific primers/NanoString) will not detect rare fusion variants, potentially compromising an opportunity for targeted therapy for those patients. The rare KIAA1549:BRAF ex13:ex11 fusion variant was only described in one case of spinal glioneuronal tumor [19]. RAF:QKI1 is known to activate MAPK/ERK and PI3K/mTOR signaling and was already described in a single case report of an adult diagnosed with spinal pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [20]. Moreover, some other larger studies focused on single nucleotide variants rather than gene fusions in the adult population and therefore were unable to capture the whole landscape of fusions related to pediatric sLGG [21, 22].

Methylation profiling using Heidelberg classification [9] was demonstrated as a powerful research tool in pediatric CNS tumors. We employed the whole-genome DNA methylation array to uncover epigenetic features of sLGGs. A dominant cluster with the methylation class "pilocytic astrocytoma, posterior fossa" suggested a possibility of a common cell of origin with the most frequent intracranial group of LGGs. Nevertheless, the current classifier scored 55% of tumors in our sLGGs group between 0.3 and 0.97. This was in keeping with t-SNE analysis demonstrating these tumors form a cluster nearby the PA-PF cluster. This data could suggest distinct epigenetic features of sLGGs compared to PA-PF. Moreover, tumors clustering with rare methylation classes were detected, in particular DLGNT, HGAP, and PXA. Three DLGNT cases were circumscribed as spinal cord lesions without any evidence of dissemination through the neuroaxis. HGAP and PXA were represented by cases with uncharacteristic histology (not clear LGGs), either anaplastic astrocytoma or anaplastic ependymoma, presence of NTRK2 fusions, and long-term survival. Several cases (n = 3) did not match any methylation classes suggesting either high normal tissue content or a rare entity yet to be defined [23]. Previous study attempted to characterize spinal cord gliomas using methylation profiling. The cohort consisted of 19 adults and seven children with high-grade and low-grade gliomas, and therefore a portion of cases clustered with Diffuse Midline Glioma H3FA3-positive and glioblastoma IDH wild-type. They also described two adult cases with HGAP and very short survival, two cases with IDH mutant glioma, and one DLGNT. Eight cases matched with pilocytic astrocytoma, but the tissue was not available to perform RNA sequencing, and therefore authors were not able to demonstrate the presence of characteristic fusions [24].

Comprehensive genomic analysis was critical not only to uncover the molecular landscape of pediatric sLGGs but also to identify high-priority targets for novel therapies. In particular, targeted therapy was used in four sLGGs patients with progressive disease who presented with neurological decline. Previously, MEK-inhibitor trametinib was shown to benefit a proportion of patients with progressive NF1 or BRAF-driven LGGs [25, 26], and our series of cases suggest clinical benefit with objective responses documented on magnetic resonance imaging in sLGGs. In addition, NTRK inhibitors have shown high efficacy in multiple NTRK-driven cancers [27], and our case demonstrated significant clinical benefit of such therapy in the patient with NTRK2 fused sLGG.

A relatively small cohort size, short follow-up, and retrospective data collection did not allow a more comprehensive prognostic marker evaluation. Furthermore, volumetry was used as a method for response evaluation considering bidimensional measurement less feasible [28], especially in our sLGG patients frequently suffering from significant spinal deformities. Therefore, response assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology (RAPNO) was not implemented in this study [29].

Nevertheless, we have assembled a coherent group of solely pediatric patients with extensive molecular analysis, and our data demonstrated the importance of integrative molecular-pathological diagnosis and enlightening the potential of targeted treatment for sLGGs. Future large prospective studies evaluating prognostic markers, the efficacy of targeted therapies, and volumetric response assessment in sLGG are needed.

Conclusion

This study provides essential data on the molecular background of purely pediatric cohort of anatomically defined low-grade gliomas confined to the spinal cord. Methylation profiling revealed epigenetic landscape of sLGG demonstrating that 55% of cases cluster with posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytoma samples with the remaining 45% being very heterogeneous. Despite this epigenetic heterogeneity, sLGGs harbor driver alterations within MAPK pathway. In contrast to the intracranial LGGs, non-BRAF fusions (including NTRK fusions) and rare KIAA1549:BRAF variants, including novel variant ex9:ex10, represent frequent molecular drivers in sLGG. Our data clearly demonstrated the presence of druggable targets, and our case series demonstrated promising results in disease control with targeted therapy. However, further research and prospective clinical trials are required to evaluate the role of targeted therapy in sLGG patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets are publically available at Mendeley Data https://doi.org/10.17632/xzkgt4jvm2.1.

Change history

11 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-022-01467-9

Abbreviations

- ATRT:

-

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CS:

-

Calibrated score

- DLGNT:

-

Diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- Ex:

-

Exon

- FGFR:

-

Fibroblast growth factor receptors

- GNT:

-

Glioneuronal tumor

- HGAP:

-

High-grade astrocytoma with piloid features

- IDH:

-

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LGG:

-

Low-grade glioma

- LGNT:

-

Low-grade glioneuronal tumor

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen‑activated protein kinase

- MC:

-

Methylation class

- MEK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MLPA:

-

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NTRK:

-

Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase

- PA-PF:

-

Pilocytic astrocytoma–posterior fossa

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PXA:

-

Pilomyxoid astrocytoma

- RAPNO:

-

Response assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- sLGGs:

-

Spinal low-grade gliomas

References

Barker DJP, Weller RO, Garfield JS (1976) Epidemiology of primary tumours of the brain and spinal cord: a regional survey in southern England. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 39:290–296

Constantini S, Miller DC, Allen JC, Rorke LB, Freed D, Epstein FJ (2000) Radical excision of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: surgical morbidity and long-term follow-up evaluation in 164 children and young adults. J Neurosurg Spine 93:183–193

Gnekow AK, Kandels D, Van TC, Azizi AA, Opocher E, Stokland T et al (2019) SIOP-E-BTG and GPOH guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents with low grade glioma. Klin Padiatr 231:107–135

Beneš V, Barsa P, Beneš V, Suchomel P (2009) Prognostic factors in intramedullary astrocytomas: a literature review. Eur Spine J 18:1397–1422

Grob ST, Nobre L, Campbell KR, Davies KD, Ryall S, Aisner DL et al (2020) Clinical and molecular characterization of a multi-institutional cohort of pediatric spinal cord low-grade gliomas. Neuro-Oncol Adv 2:1–9

Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S et al (2012) 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging 30:1323–1341

Tian Y, Rich BE, Vena N, Craig JM, MacConaill LE, Rajaram V et al (2011) Detection of KIAA1549-BRAF fusion transcripts in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded pediatric low-grade gliomas. J Mol Diagn 13:669–677

Uhrig S, Ellermann J, Walther T, Burkhardt P, Frohlich M, Hutter B et al (2021) Accurate and efficient detection of gene fusions from RNA sequencing data. Genome Res 31:448–460

Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V, Schrimpf D, Sturm D et al (2018) DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 555:469–474

Cocco E, Schram AM, Kulick A, Misale S, Won HH, Yaeger R et al (2019) Resistance to TRK inhibition mediated by convergent MAPK pathway activation. Nat Med 25:1422–1427

Jones DTW, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Bäcklund LM, Ichimura K et al (2008) Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res 68:8673–8677

Pfister S, Janzarik W, Remke M, Ernst A, Werft W, Becker N et al (2008) BRAF gene duplication constitutes a mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Invest 118(5):1739–1749

Konar SK, Bir SC, Maiti TK, Nanda A (2017) A systematic review of overall survival in pediatric primary glioblastoma multiforme of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg Pediatr 19:239–248

Ryall S, Zapotocky M, Fukuoka K, Nobre L, Guerreiro Stucklin A, Bennett J et al (2020) Integrated molecular and clinical analysis of 1000 pediatric low-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell 37:569–583.e5

Ater JL, Zhou T, Holmes E, Mazewski CM, Booth TN, Freyer DR et al (2012) Randomized study of two chemotherapy regimens for treatment of low-grade glioma in young children: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 30:2641–2647

Gnekow AK, Walker DA, Kandels D, Picton S, Perilongo G, Grill J et al (2017) A European randomised controlled trial of the addition of etoposide to standard vincristine and carboplatin induction as part of an 18-month treatment programme for childhood (≤16 years) low grade glioma: a final report. Eur J Cancer 81:206–225

Clarke M, Mackay A, Ismer B, Pickles JC, Tatevossian RG, Newman S et al (2020) Infant high-grade gliomas comprise multiple subgroups characterized by novel targetable gene fusions and favorable outcomes. Cancer Discov 10:942–963

Guerreiro Stucklin AS, Ryall S, Fukuoka K, Zapotocky M, Lassaletta A, Li C et al (2019) Alterations in ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET drive a group of infantile hemispheric gliomas. Nat Commun 10:1–13

Chiang JCH, Harreld JH, Orr BA, Sharma S, Ismail A, Segura AD et al (2017) Low-grade spinal glioneuronal tumors with BRAF gene fusion and 1p deletion but without leptomeningeal dissemination. Acta Neuropathol 134:159–162

Daoud EV, Wachsmann M, Richardson TE, Mella D, Pan E, Schwarzbach A et al (2019) Spinal pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with a QKI-RAF1 fusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 78:10–14

Chai RC, Zhang YW, Liu YQ, Chang YZ, Pang B, Jiang T et al (2020) The molecular characteristics of spinal cord gliomas with or without H3 K27M mutation. Acta Neuropathol Commun 8:1–11

Zhang M, Iyer RR, Azad TD, Wang Q, Garzon-Muvdi T, Wang J et al (2019) Genomic landscape of intramedullary spinal cord gliomas. Sci Rep 9:1–8

Lebrun L, Bizet M, Melendez B, Alexiou B, Absil L, Van Campenhout C et al (2021) Analyses of DNA methylation profiling in the diagnosis of intramedullary astrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 80:663–673

Biczok A, Strübing FL, Eder JM, Egensperger R, Schnell O, Zausinger S et al (2021) Molecular diagnostics helps to identify distinct subgroups of spinal astrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun 9:119

Selt F, Van Tilburg CM, Bison B, Sievers P, Harting I, Ecker J (2020) Response to trametinib treatment in progressive pediatric low-grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol 149:499–510

Kondyli M, Larouche V, Saint-Martin C, Ellezam B, Pouliot L, Sinnett D et al (2018) Trametinib for progressive pediatric low-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol 140:435–444

Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, DuBois SG, Lassen UN, Demetri GD et al (2018) Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med 378:731–739

D’Arco F, O’Hare P, Dashti F, Lassaletta A, Loka T, Tabori U et al (2018) Volumetric assessment of tumor size changes in pediatric low-grade gliomas: feasibility and comparison with linear measurements. Neuroradiology 60:427–436

Fangusaro J, Witt O, Hernáiz Driever P, Bag AK, de Blank P, Kadom N et al (2020) Response assessment in paediatric low-grade glioma: recommendations from the Response Assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology (RAPNO) working group. Lancet Oncol 21:e305–e316

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, Grant No. NU21-07-00419 (DS, AV, MZ, JS), PRIMUS/19/MED/06 Charles University Grant Agency, Prague, Czech Republic (MZ, LK, AM, KV), GAUK No. 204220, MH CZ–DRO, University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic (00064203) (DS, AV, MZ, JS), The project National Institute for Cancer Research (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5102)—Funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. Foundation Národ dětem and Foundation 1000 statečných.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: AM, LK, MZ. Data collection: AM, KV, PL, JT, IP, TS. Molecular-genetic experiments: AM, AV, LS, LK. Imaging data analysis: MK, ZH. Histology revision: MK, JZ. Interpretation of the data: AM, MZ, LK, AV, PB, DJ, MS. Critical revision of the article: MZ, DS, LS, VB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent were waived.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from parent or legal guardian. Institutional consent form was used.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the given names and family names of all authors were erroneously transposed and this was corrected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Table of primers used to validate the fusion transcripts identified by RNA sequencing.

Additional file 2: Table S2

. Table showing the complete sLGGs cohort emphasizing the original histology before molecular pathology reevaluation, anatomical location, and molecular-biology data.

Additional file 3: Fig. S1

. A total number of pediatric intracranial LGG patients with known genetic alteration is dividedby anatomical location. Importantly, KIAA1549:BRAF ex9:ex10 variant fusion was detected solely in the upperspine.

Additional file 4: Fig. S2

. T-SNE analysis displaying Prague samples (large red dots) among reference cohort samples.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Misove, A., Vicha, A., Broz, P. et al. Integrated genomic analysis reveals actionable targets in pediatric spinal cord low-grade gliomas. acta neuropathol commun 10, 143 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-022-01446-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-022-01446-0