Abstract

Recurrent C11orf95-RELA fusions (RELAFUS) are the hallmark of supratentorial ependymomas. The presence of RELA as the fusion partner indicates a close association of aberrant NF-κB activity with tumorigenesis. However, the oncogenic role of the C11orf95 has not been determined. Here, we performed ChIP-seq analyses to explore genomic regions bound by RELAFUS and H3K27ac proteins in human 293 T and mouse ependymoma cells. We then utilized published RNA-Seq data from human and mouse RELAFUS tumors and identified target genes that were directly regulated by RELAFUS in these tumors. Subsequent transcription factor motif analyses of RELAFUS target genes detected a unique GC-rich motif recognized by the C11orf95 moiety, that is present in approximately half of RELAFUS target genes. Luciferase assays confirmed that a promoter carrying this motif is sufficient to drive RELAFUS-dependent gene expression. Further, the RELAFUS target genes were found to be overlapped with Rela target genes primarily via non-canonical NF-κB binding sites. Using a series of truncation and substitution mutants of RELAFUS, we also show that the activation domain in the RELAFUS moiety is necessary for the regulation of gene expression of these RELAFUS target genes. Lastly, we performed an anti-cancer drug screening with mouse ependymoma cells and identified potential anti-ependymoma drugs that are related to the oncogenic mechanism of RELAFUS. These findings suggested that RELAFUS might induce ependymoma formation through oncogenic pathways orchestrated by both C11orf95 and RELA target genes. Thus, our study unveils a complex gene function of RELAFUS as an oncogenic transcription factor in RELAFUS positive ependymomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ependymomas are primary glial tumors that can occur in all ages and locations of the central nervous system [39]. Current therapeutic options for all tumors largely depend on maximal safe surgical resection and radiation therapy, whereas no significant survival benefit was observed for standard chemotherapy [34, 43, 68]. Recent large-scale genome sequencing studies of ependymomas have identified nine molecular subgroups associated with distinct genomic alterations, clinical behavior, age distribution, and anatomical location [44]. Supratentorial ependymomas are characterized by mutually exclusive recurrent RELA and YAP1-related gene fusions, thereby being segregated into two subgroups denoted as ST-EPN-RELA and YAP1 [44]. The ST-EPN-RELA subgroup displays a dismal prognosis, and incomplete surgical resection of these tumors is associated with increased recurrence rates and poor outcome, signifying that the development of new therapies is essential for these cases [9, 34, 44, 68]. Thus, the identification of clinically relevant subtypes and oncogenic drivers could provide the opportunity to develop specific targeted therapies for individual tumor types.

Recurrent C11orf95-RELA fusion (RELAFUS) genes were identified in a large fraction of supratentorial ependymomas [45]. RELAFUS1 (Type 1) and RELAFUS2 (Type 2), the two most frequent fusion variants are potent driver oncogenes capable of inducing human ependymoma-like tumors in mice, and therefore likely represent the tumor-initiating events in human patients [41, 45, 60]. RELA is a well-known master transcription factor in the NF-κB pathway, which is intimately involved in various pathophysiological processes such as inflammation and cancer [6, 69]. Upon external stimuli, RELA is released from IκBα-mediated cytoplasmic sequestration and translocated into the nucleus, thereby transcriptionally regulating the expression of the target genes [69]. Given that the fusion protein preferentially localizes in the nucleus, persistent activation of the NF-κB pathway is thought as the primary mechanism for the RELAFUS -driven ependymoma formation as bolstered by high NF-κB activity in human and mouse RELAFUS tumors [41, 45]. However, dysregulation of many non-NF-κB pathways was also commonly identified in these tumors. Furthermore, expression of wild type RELA or activating RELA mutants failed to induce brain tumor formation in mice, strongly suggesting an important role of non-NF-κB pathways in the RELAFUS-driven ependymoma formation [41, 45].

The recent identification of active super-enhancers (SE) specific to human RELAFUS ependymomas gave significant insights into the activated oncogenic pathways and potential therapeutic targets in these tumors [31]. Although a subset of these super-enhancers highlighted oncogenic driver genes and pathways associated with tumorigenesis, not all direct targets of RELAFUS could be identified due to the technical limitations in accurately determining enhancer target genes [46]. Further, transcription factors generally function in a context-dependent manner [24]. Therefore, a different approach would be useful to further scrutinize genes directly regulated by RELAFUS. Here, to dissect the oncogenic program underlying ependymoma formation, we explored transcriptional target genes directly regulated by the RELAFUS1-HA protein using HA tag and H3K27ac-ChIP-seq analyses in human 293T and mouse ependymoma cells, and uncovered the complex epigenetic regulation by RELAFUS1. In addition, we performed an anti-cancer drug screening to validate the potential therapeutic relevance of downstream effectors driven by RELAFUS1 targets. Our study further deepens our understanding of the molecular functions of RELAFUS in driving tumorigenesis, thus providing significant clues to identify therapeutic targets for RELAFUS positive ependymomas [31].

Materials and methods

Generation of murine RELAFUS1 tumors

All animal experiments were done in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and followed NIH guidelines for animal welfare. The RCAS/tv-a system used in this work has been described previously [16,17,18, 41, 42]. Mouse RELAFUS1 tumors were generated with the injection of RCAS-RELAFUS1 or RELAFUS1-HA virus into newborn pups brains in N/tv-a;Ink4a-Arf−/−;Ptenfl/fl mice. The mice were sacrificed when they developed symptoms of the disease and the brain tumors were used for the generation of tumor cell lines.

Generation of mouse neurosphere and ependymoma cell lines

Neurosphere lines were generated by mechanical dissociation from forebrains of newborn pups in N/tv-a;Ink4a-Arf−/−;Ptenfl/fl or B/tv-a mice and then maintained in serum-free neurosphere medium (Stem Cell Technologies) [4, 41]. Murine ependymoma cell lines were generated by mechanical dissociation from brain tumors driven by RCAS-RELAFUS1 (H41, H57 and H59) or RCAS-RELAFUS1-HA (H1203) and then maintained as adherent cells in serum-free neurosphere medium (Stem Cell Technologies) [41]

Cell culture, transfections and infections

293T cells (ATCC: CRL-3216) and DF-1 cells (ATCC: CRL-12203) were maintained according to the manufacture’s protocol. RCAS virus was produced in DF-1 packaging cells as previously described [16,17,18]. Transient transfection of luciferase reporter and/or RCAS plasmids into 293T or 293T/tv-a cells was performed with X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent according to the manufacture’s protocol (Merck by Roche). 293T/tv-a cell lines lentivirally expressing the tv-a-myc/6xHis were generated with standard protocol and maintained in a medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin as previously described [42]. For the generation of 293T/tv-a cells expressing the relevant RCAS virus, cells were subjected to retroviral infection using the RCAS viral supernatant in the DF-1 cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (ChIP-seq)

293T/tv-a cells infecting RCAS-RELAFUS1-HA, RELAFUS1−S486E-HA and mEPN cells (H41 and H1203) were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, stopped the fixation with 0.125 M glycine, and then collected ice-cold 1 × PBS(−) containing 1 mM PMSF according to the standard protocol. Nuclei preparation and chromatin digestion was performed according to manufacturer's instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, #9003) with modification [20]. Nuclei pellets were resuspended with ChIP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM PMSF and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail). Samples were sonicated by using Bioruptor II (BM Equipment, BR2006A) to generate DNA fragments of ~ 200 base pairs. Antibodies (2 µg) for H3K27ac (Abcam, #4729, Lot GR3252404) or HA (Abcam, #9110, Lot GR235874-5) were added into the sheared chromatin (10 ~ 30 µg), and incubated in an ultrasonic water bath for 30 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, supernatants were incubated with FG Beads HM Protein G (Tamagawa Seiki, TAB8848N3173) for 30 min at 4 °C. Beads were washed twice with ChIP buffer and washed with Wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate and 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0) and LiCl buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 250 mM LiCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate and 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). Immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted and reverse-crosslinked according to manufacturer's instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, #9003). Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified by using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, #28106). DNA libraries were prepared by using QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit (QIAGEN, #180492). The size determination and quantification of DNA libraries was done by qPCR (New England Biolabs, E7630) and by using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. DNA libraries were sequenced on Illumina sequencers (Illumina HiSeq 3000 or NovaSeq 6000). Detailed antibody information, library preparations and Illumina sequencers in this study were described in Additional file 9: Table S1A.

ChIP-seq data analysis

The RelA ChIP-seq datasets in murine embryonic fibroblasts after three hours of TNF stimulation were obtained from GSE132540 [37]. Sequencing reads from ChIP-seq experiments were mapped to the hg19 version of the human genome or mm9 version of the mouse genome with Bowtie (v2.2.9) and parameters–local, respectively [25]. Gene annotations were obtained from Ensemble (v.75). Duplicate reads were removed by Samtools (v1.3.1). Heatmaps to visualize enriched regions (ERs) around TSS ± 10 kb were generated with NGSplot (v2.63) [56]. The normalized ERs were visualized with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v2.3.91) [50]. ChIP-seq ERs were called using MACS (v1.4.2) with the default parameters (p value cutoff; 1e-5) with the relevant input as control [70]. ChIP-seq peak statistics were summarized in Additional file 9: Table S1A. A correlation heatmap to evaluate the relationship between samples was generated by DiffBind (v2.4.8) [52]. For the differential binding analyses, we consolidated the peaks into a consensus set using a “minOverlap” of 2. The count reads were then TMM normalized implemented in DiffBind. Batch annotation of ERs was performed using ChIPpeakAnno (v3.10.2) as a Bioconductor package [73] within the statistical programming environment R (v3.4.1). Motif analyses of C11orf95-RELA fusion and Rela protein binding sites were performed using MEME-ChIP (v5.0.1) with sequences of ERs [30]. Overlapping peaks of ERs between different ChIP-seq experiments were obtained by using “findOverlapsOfPeaks” function under the default setting in ChIPpeakAnno. This setting counts the peaks as the minimal involved peaks in any group of connected/overlapped peaks. Super-enhancers were defined by H3K27ac peak rank order using ROSE algorithm [29, 65]. Enhancer profiles specific for human ST-EPN-RELA ependymomas and RELA-EnhancerAssociatedGene (Subgroup specific enhancers and super enhancers detected in ST-EPN-RELA ependymoma) were obtained in the previous study [31]. For the purpose of pathway enrichment analysis, gene ontology networks were generated using ClueGO (v2.5.1) [3] through Cytoscape (v3.6.1) [55]. We used the following ontologies: KEGG_20.11.2017 and REACTOME_Pathways_20.11.2017. To calculate enrichment/depletion tests, two-sided tests based on the hypergeometric distribution were performed. To correct the p values for multiple testing, Bonferroni step down method was used. We used min:3 max:8 GO tree interval, a minimum of 3 genes per GO term, kappa score of 0.4.

Lists of the target gene were generated by removing duplicate gene annotations from the peak list obtained at TSS ± 10 kb (Additional file 9: Table S1E). A list of ‘previously reported-NFkB target genes’ was previously described [12, 41]. For comparison of our mouse gene list to the human, all mouse gene symbols were converted to humans using the MGI homology map with the BioMart browser in the Ensembl database. The normalized ChIP-seq tracks were visualized on the IGV genome browser (v2.3.91). RELAFUS1-HA, RELAFUS1−S486E-HA, Rela, H3K27ac and input peaks are shown with the same scale in each figure (Fig. 5b, c, i, j, Additional file 5: S4B, E, F and Additional file 7: S6D). 5′-BGKGGCCCCBG-3′ (B = C or G or T, K = G or T) and 5′-GGGRNWYYCC-3′ (R = A or G, N = any base, W = A or T, and Y = C or T) sequences were used to find a genomic position of the 293T-RELAFUS1-MEME-2 and canonical NF-κB consensus motif, respectively. The position of the 293T-RELAFUS1-MEME-2 and κB site is shown as a blue vertical bar on positive (+) and negative (−) DNA strands. Transcriptional start sites (TSSs) were analyzed using the DBTSS; Data Base of Transcriptional Start Sites online tool [59]. Representative images in two technical replicates were shown in the figures.

RNA-seq datasets and gene expression analysis

For gene expression analyses, RNA-seq datasets of human ependymomas and mouse brain tissues were obtained from the Pediatric Cancer Genome Project (PCGP, EGAS00001000254) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE93765), respectively [7, 41, 45]. The human ependymoma samples were analyzed between RELAFUS positive ST-EPNs and all negative ependymomas including RELAFUS negative ST-EPNs and PF-EPNs. The aligned reads were counted for gene associations against the Ensemble genes database with featureCounts (v1.5.0) [27]. Transcriptomic signature genes of ST-EPN in single-cell RNA-seq analysis were obtained in the previous publication and used for an overlapping analysis with RELAFUS1 target genes [13]. Microarray gene expression data of the human ST-EPN-RELA and YAP1 subgroup was obtained from publicly available data (GSE64415) and used for pathway enrichment analysis [44]. Differential expression analyses were performed using the R/Bioconductor package edgeR (v3.18.1) [51]. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v7.0.0).

Vector constructs

All vectors and sgRNA target sequences used in this study are listed in Additional file 14: Table S6A. The DNA fragments for the RELAFUS1 and C11orf95 mutant vector construction were PCR-amplified on the relevant DNA template to obtain appropriate restriction sites and then inserted in RCAS vector.

The luciferase reporter vectors for the RELAFUS1-motifs were generated by insertion of the synthetic oligonucleotide for the relevant motif sequence as between Kpn I and EcoRV sites in the pNL3.2 vector containing the minimal promoter (Promega). The C11orf95 5′-upstream luciferase reporter construct was generated by PCR-amplifying the human C11orf95 gene sequence from genomic DNA of 293T cells. The PCR fragment was then subcloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) to obtain appropriate restriction sites and subsequently inserted into the pNL3.2 (minimal promoter) vector (Promega). For RCAS-C11orf95-NLS-VP64-HA (CNVP-HA) and lentiCRISPRv2-dCas9-sgGFP1 vector construction, SV40-NLS-VP64-HA and sgGFP target sequences as previously described, were synthesized and inserted in the relevant vector, respectively [47, 54].

pLJM1-EGFP was a gift from David Sabatini (Addgene plasmid #19319; http://n2t.net/addgene:19319; RRID: Addgene_19319) [53]. psPAX2 was a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12260; http://n2t.net/addgene:12260; RRID: Addgene_12260). pMD2.G was a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12259; http://n2t.net/addgene:12259; RRID: Addgene_12259). lentiCRISPR v2-dCas9 was a gift from Thomas Gilmore (Addgene plasmid #112233; http://n2t.net/addgene:112233; RRID: Addgene 112233).

Western blot analysis

Cells were cultured, lysed, and processed for western blotting as previously described [41]. Antibodies were listed in Additional file 14: Table S6C. All western blot analyses were performed at least twice and successfully repeated in the experiments. The representative images were shown in the figures.

For immunoblot and qPCR analyses in 293T cells as shown in Fig. 3j–l, 5g and Additional file 5: Fig. S4C, RCAS vectors were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmid concentration to adjust the protein expression level between samples. After 48 h of the transfection, cells were collected and split for RNA and protein extractions. Then, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. RNAs were used for subsequent qPCR analysis.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis

Total RNAs were extracted from mEPN cells or 293T cells using the miRNeasy or RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) and were used to synthesize cDNA by using the SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SYBR Green real-time PCR was performed using the relevant gene-specific primer sets, PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (2X) (ThermoFisher SCIENTIFIC), and Fast run protocol from Applied Biosystems in a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System. The ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the relative gene expression normalized to the reference gene (RPS18 or Rps18). Each biological replicate in the PCR reaction was assayed in four technical replicates. Data (mean ± SD) are displayed as the relative ratio to the relevant control sample (e.g. GFP cells). Circles in the figure indicate relative mean values of each biological replicate. Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. All primers used in this study are listed in Additional file 14: Table S6B [64].

Luciferase reporter assay

293T/tv-a cells retrovirally infecting the relevant RCAS virus were seeded at a density of 7.5 × 104 cells in a 24 well format in triplicates the day prior to transfection. Cells were then co-transfected pGL4.53[luc2/PGK] (control vector) and pNL3.2 (test vector) with 1:9 ratio (total 0.2 μg/well) using X-treamGENE9 transfection reagent (Roche) in 500 μL/well of culture medium. After 24 h of the transfection, cells were lysed with the Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega E1941) (100 μL/well) and the lysates of 80 μL/well were transferred in white 96 well plates, followed by analyzed for luciferase activity using the Nano-Glo Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega N1630) on a GloMax Explorer luminometer (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

For analysis in transient expression of RCAS vectors as shown in Fig. 3g, h, 5h, 293T cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells in a 6 well format the day prior to transfection. Cells were then co-transfected pGL4.53[luc2/PGK] (control vector), pNL3.2 (test vector) and RCAS vector with 1:9:10 ratio (total 2 μg) using X-treamGENE9 transfection reagent (Roche) in 2 mL/well of culture medium. After 24 h of the transfection, cells were lysed with the Passive Lysis Buffer of 500 μL/well and the lysates of 80 μL/well were transferred in white 96 well plates in triplicate, followed by analyzed for luciferase activity as well.

Relative luciferase activity was calculated as the ratio of NanoLuc normalized to Firefly luciferase and GFP control cells. The box plots in all luciferase reporter assays extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. Whiskers of all box plots extend to the most extreme data point. Circles in the box plots indicate relative mean values of each biological replicate. Analysis was done using repeated measures (RM) one-way ANOVA or paired two-tailed t-test using Graph-Pad Prism 8 software, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Immunofluorescence

For analysis of subcellular localization of C11orf95-HA, RELA-HA and RELAFUS1-HA proteins, DF-1 cells infecting the relevant RCAS viruses grown on Lab-Tek Chamber Slide (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Subsequently, cells were immunostained with an anti-HA tag (Roche, 11867423001) antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen #A21210). The analysis was performed by immunofluorescent microscopy (Leica DMI6000 microscope, FW4000 software). GFP fusion proteins were observed using fluorescent microscopy (OLYMPUS CKX53 microscope and cellSens Standard software).

Anti-cancer drug screening

H41- and H1203-mEPN cells (5,000/well) were seeded on a 384-well culture plate in mouse neurosphere medium in duplicate (Stem Cell Technologies) and cultured overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 (day 0). Ten micromolar of 164 FDA-approved anti-cancer drugs and 15 selected potential NF-κB inhibitors (final 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) was then added to the cells using the Bravo Automated liquid handling platform (Agilent technologies) (day 1), and cell viability was assessed with a CCK-8 kit (Cell Counting Kit-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) after 72 h of incubation (day1 to day 4) (Additional file 13: Table S5A, B). The mean cell viability (% of control) was calculated (n = 2) as follows: (A sample-A blank)/(A 0.1% DMSO-treated control-A blank) (where, A = Absorbance at 450 nm) and experiments were repeated twice. Two Sorafenib Tosylate (SPL30 and SPL180) and Vorinostat (SPL70 and SPL179) from the different suppliers were tested in this screening because of redundancy between two drug libraries.

To determine the cell sensitivity to these drugs, anti-cancer drugs serially diluted in mouse neurosphere medium were added to the mEPN cells in duplicate and cultured for 72 h. Cell viability was then assessed by a CCK-8 kit as well. IC50 values were calculated by drawing four-parameter curve fitting using GraphPad Prism (version 7, GraphPad Software).

Protein domain illustrations

Illustrations of protein domain as shown in Fig. 4a, Additional file 2: Fig. S1D, Additional file 6: Fig. S5B, G and Additional file 8: Fig. S6F were generated using the IBS software (illustrator of biological sequences) [28]. In Fig. 4a, Additional file 2: Fig. S1D and Additional file 8: Fig. S 6F, Blue and red boxes represent portions of C11orf95 (UniProtKB—C9JLR9) and RELA (UniProtKB—Q04206) coding sequences, respectively. ZF, zinc finger (SPIN-DOC-like, zinc-finger); RHD, Rel homology domain; TAD, transactivation domain; black boxes in the C-terminus, HA-tag; NLS, nuclear localization signal. NLS prediction in C11orf95 protein was done using the cNLS mapper online tool (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) [22]. The amino acid position of three predicted bipartite NLSs (210–239, 254–286 and 456–487) in C11orf95 are shown as black bars and the yellow box (cut-off score = 4.0) in Fig. 4a.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses in this study were performed using GraphPad Prism 7, 8, or R software and described with the significance values and sample size in the respective figure legends, corresponding results sections, or methods section in detail.

Materials availability

All cell lines, plasmids and other reagents generated in this study are available from the corresponding authors with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

Results

HA tag ChIP-seq analyses identified unique genomic binding sites of RELAFUS1

Accumulating evidence suggests that—in addition to known NF-κB targets—also non-NF-κB target genes contribute to the tumorigenesis of RELAFUS [31, 35, 41, 45]. Therefore, to identify direct transcriptional target genes of RELAFUS and to clarify the mechanisms of how RELAFUS causes tumor formation, we initially performed an HA-tag protein immunoprecipitation and sequencing (HA ChIP-seq) analysis on 293T/tv-a cells retrovirally infected with either RCAS-RELAFUS1-HA or RELAFUS1−S486E-HA (A serine-to-glutamine substitution at Ser-486 of RELAFUS1 corresponding to Ser-276 in the Rel homology domain of RELA, which has been previously shown to severely impair the tumor-forming capacity of RELAFUS1) (Additional file 2: Fig. S1A–D; Additional file 9: Table S1A) [41]. HA ChIP-seq analyses identified a large number of significant RELAFUS1 DNA-binding sites throughout the genome (Fig. 1a, b, Additional file 2: Fig. S1E; Additional file 9: Table S1B, C). Interestingly, RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E presented an overall similar DNA-binding pattern (Fig. 1a, b). However, RELAFUS1 peaks showed somewhat higher enrichment in intronic and intergenic regions but a lower enrichment in proximal promoter regions compared to RELAFUS1−S486E (Fig. 1c, d), signifying an existence of DNA regulatory elements specific for RELAFUS1 as previously described [31].

HA tag ChIP-seq analyses identified unique genomic binding sites of RELAFUS1. a, b Genome-wide RELAFUS1-HA (a) and RELAFUS1−S486E-HA (b) binding demonstrated by HA ChIP-seq analyses in 293T/tv-a cells. Heatmaps represent HA ChIP enrichments at the regions (TSS ± 10 kb) ranked by the sum of the enrichment values. Heatmaps for two biological replicates are shown individually. Input controls are also shown. c, d Bar graphs display the genomic distribution of the RELAFUS1-HA (c) and RELAFUS1−S486E-HA (d) peaks in 293T/tv-a cells. e Volcano plot illustrating differences in gene expression between human RELAFUS positive and all negative ependymomas (DEGs: false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, n = 5507). Differences in Log2 fold change in gene expression values are plotted on the x-axis. Adjusted p values calculated using the Benjamin-Hochberg method are plotted on the y-axis. RELAFUS1 target genes annotated within the TSS ± 10 kb are shown as large circles. LMX1B, C11orf95, RELA, CCND1 and L1CAM genes are indicated by the arrows. f Scatter plots showing the mRNA expression of direct RELAFUS1 target genes in the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (logFC) between human RELAFUS positive and all negative ependymomas. Genes are grouped based on the distance of the RELAFUS1 binding to location to the TSS of the gene (FDR < 0.05, ± 50 kb- ± 1 kb; n = 870, 769, 645, 501, 350, 261, 214 and 179). The expression level of DEGs bound by RELAFUS1 within the TSS ± 10 kb were compared to those bound by RELAFUS1 at other distances as indicated in the x-axis. g, h Venn diagram showing the number of the overlapping between the RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E peaks (g) and target genes (h) identified within the TSS ± 10 kb in 293T/tv-a cells. i Scatter plots showing the mRNA expression of target genes differentially bound by RELAFUS1 and/or RELAFUS1−S486E in the DEGs (logFC) between human RELAFUS positive and all negative ependymomas. The target genes of FUS1 (DBPs for RELAFUS1: logFCDBPs > 1, FDR < 0.05, n = 64), S486E (DBPs for RELAFUS1−S486E: logFCDBPs > 1, FDR < 0.05, n = 42) and common (No differential peaks between RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E: |logFC|DBPs < 1, n = 404) are shown in the x-axis. DBPs: Differential binding peaks. Statistical differences were assessed with a Mann–Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. n.s.: not significant

We then determined which transcriptional target genes of RELAFUS1 might be involved in RELAFUS1-driven ependymoma formation. We used publicly available expression data of human ependymomas [45] and detected significantly higher expression of RELAFUS1 target genes (identified by our ChIP-seq analysis) in human RELAFUS-positive ependymomas compared to RELAFUS-negative sependymomas (Fig. 1e). Further, up-regulation of many RELAFUS1 target genes was also observed in a second ependymoma dataset (Additional file 2: Fig. S1F) [44]. We focused our subsequent analysis on genes bound by RELAFUS1 at ± 10 kb of the transcription start sites (TSSs), since these genes were significantly up-regulated compared to genes bound at ±30, 40, or 50 kb of the TSSs (Fig. 1f). We observed significant peaks of both RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E in these loci and identified 619 (in 887 peaks) and 446 (in 592 peaks) direct target genes of RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E, respectively (Fig. 1g, h; Additional file 9: Table S1B–E). Interestingly, more than half of the RELAFUS1−S486E target genes (64%; 287 out of 446 RELAFUS1−S486E target genes) still overlapped with the RELAFUS1 target genes (46%; 287 out of 619 RELAFUS1 target genes) (Fig. 1h). Notably, when comparing the expression of genes that were occupied by either only RELAFUS1 or only RELAFUS1−S486E (at TSS ± 10 kb) in human RELAFUS-positive versus negative ependymomas, we observed a significantly lower up-regulation of RELAFUS1−S486E target genes (Fig. 1i), signifying that the transcriptional activity of the mutant form might be somewhat impaired, thus likely explaining the lack of the tumor-forming potential [41]. These results suggest that RELAFUS1 might function as a transcription factor and induce aberrant gene expression for ependymoma formation.

Most RELAFUS1 target genes are actively transcribed

To further characterize RELAFUS1 target genes, we also investigated the transcriptional profile of RELAFUS1 in mouse ependymoma (mEPN) cells derived from the RCAS-RELAFUS1-HA-driven ependymoma (H1203 cells) (Additional file 3: Fig. S2A; Additional file 9: Table S1A) [41]. HA ChIP-seq analysis of the mEPN cells successfully identified a large number of the RELAFUS1 binding sites throughout the entire genome (Fig. 2a; Additional file 10: Table S2A). We observed a higher frequency of RELAFUS1 peaks in intronic and a lower frequency in proximal promoter regions in mEPN cells, compared to 293T-RELAFUS1 cells (Figs. 1c, 2b). We then examined the expression levels of RELAFUS1 target genes in RNA-seq data of normal mouse brains, PDGFA-driven gliomas, and RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas (Fig. 2c–f) [41]. We observed that many RELAFUS1 target genes were significantly up-regulated in RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas compared to both normal brains (Fig. 2c, d) and PDGFA-driven gliomas (Fig. 2e, f). We again observed that RELAFUS1 target genes bound within ± 10 kb of the TSS were significantly up-regulated (Fig. 2d, f) and thus focused our subsequent analysis on these genes. We identified 520 RELAFUS1 target genes from 649 RELAFUS1 peaks in the mEPN cells (Additional file 9: Table S1E, Additional file 10: Table 2A). We observed that a significant portion of these genes was commonly up- or down-regulated in RELAFUS1-driven mouse ependymomas compared to normal brains or PDGFA-driven gliomas, indicating the creation of a RELAFUS1-specific transcriptional network (Fig. 2g, h). Of note, dysregulation of PDGF signaling in human and mouse RELAFUS tumors has been previously shown [41, 44, 45]. However, it is noteworthy that the RELAFUS-specific transcriptional program was observed even when compared to the PDGF-driven mouse glioma samples in our analysis, thus implying that RELAFUS likely induces tumor formation by co-activating several oncogenic pathways driven by the activation of several RELAFUS target genes in addition to PDGF signaling.

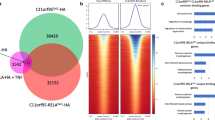

Most RELAFUS1 target genes are actively transcribed. a Genome-wide RELAFUS1-HA binding or H3K27ac marks in mEPN (H1203) cells. The enrichment of H3K27ac within the RELAFUS1-HA binding region is shown in heatmaps. b Bar graphs display the genomic distribution of the RELAFUS1 peaks in H1203 cells. c, e Volcano plots illustrating differences in gene expression between RCAS-RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas (FUS1) and mouse normal brains (NB) (c) or RCAS-PDGFA-driven glioblastomas (PDGFA) (e) (FDR < 0.05, n = 11,574 (c), n = 8,059 (e)). Differences in Log2 fold change in gene expression values are plotted on the x-axis. Adjusted p values calculated using the Benjamin-Hochberg method are plotted on the y-axis. RELAFUS1 target genes annotated within the TSS ± 10 kb in H1203 cells are shown as large circles. 2700081O15Rik, Ccnd1 and Lmx1b genes are indicated by the arrows. d, f Scatter plots showing the mRNA expression of direct RELAFUS1 target genes in the DEGs (logFC) between RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas and normal brains (d) or PDGFA-driven glioblastomas (f). Genes are grouped based on the distance of the RELAFUS1 binding to location to the TSS of the gene (FDR < 0.05, ± 50 kb- ± 1 kb; n = 1,083, 943, 826, 668, 511, 412, 342 and 295). The expression level of DEGs bound by RELAFUS1 within the TSS ± 10 kb were compared to those bound by RELAFUS1 at other distances as indicated in the x-axis. g, h Venn diagram showing the number of the overlapping of up- and down-regulated RELAFUS1 target genes (within TSS ± 10 kb) in RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas relative to normal brains or PDGFA-driven glioblastomas. i Venn diagram showing the number of the overlapping of H3K27ac peaks in H41 plus H1203 cells and RELAFUS1 peaks in H1203 cells. j Venn diagram showing the number of the overlapping of RELAFUS1 peaks and super-enhancers (SEs) identified in H1203 cells. k Inflection plots representing SEs in H41 and H1203 cells. Representative genes are shown along with their rankings. l, m Venn diagrams showing the number of the overlapping of Rela peaks in MEFs after 3 h of TNF stimulation (see Methods) and RELAFUS1 peaks in H1203 cells (l) or H3K27ac peaks within the entire genome (m) in H41 and H1203 cells. n, o Venn diagrams showing the number of the overlapping of Rela target genes in MEFs and RELAFUS1 target genes in H1203 (n) or 293T (o) cells. Statistical tests are as described in Fig. 1

Subsequently, to examine whether these RELAFUS1 target genes were actively transcribed, we performed H3K27ac ChIP-seq (a histone mark of active chromatin) with two mEPN (H41 and H1203) cells and investigated actively transcribed regions, including promoters and enhancers (Fig. 2a, Additional file 3: Fig. S2A, B; Additional file 9: Table S1A, Additional file 10: Table S2B, C). We identified 36,859 peaks that were present in both mEPN cells (Fig. 2i, Additional file 3: Fig. S2C). Interestingly, most of the RELAFUS1 peaks in the TSS ± 10 kb region overlapped with H3K27ac peaks (94%; 812 out of 867 RELAFUS1 peaks, p = 9.4 × 10–271) (Fig. 2i). Furthermore, 41% of RELAFUS1 peaks overlapped with super-enhancers (SEs) identified by an exceptionally high degree of enrichment of H3K27ac peak (Fig. 2j, k, Additional file 3: Fig. S2D; Additional file 10: Table S2D–F) [48, 65]. We noticed that some RELAFUS1 peaks (TSS ± 10 kb) overlapped with SE regions that were annotated to well-known cancer-associated genes such as CCND1 (a representative NF-κB target gene) [14, 15], PIK3R2 (proto-oncogene), DOT1L (histone modifier gene) in addition to RELA and 2700081O15Rik (mouse homolog of C11orf95) (Fig. 2k; Additional file 10: Table S2F). Further, we also found that enhancer- and SE-annotated genes identified in mouse ependymoma cells and human RELAFUS tumors were significantly overlapping (Additional file 3: Fig. S2E, F), thus supporting a close association of our analysis with human ependymomas [31].

To further dissect the molecular mechanism of RELAFUS-driven ependymoma formation, we examined the implication of RELA target genes in the RELAFUS1 transcription network using publicly available Rela ChIP-seq data in murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) after TNF stimulation [37]. We found that approximately 22% of RELAFUS1 peaks in mEPN cells overlapped with Rela peaks in MEFs (Fig. 2l) as also supported by a significant overlap between the H3K27ac peaks in mEPN cells and Rela peaks in MEFs (Fig. 2m). More specifically, approximately 27 and 10% of RELAFUS1 target genes in mEPN and 293T-RELAFUS1 cells overlapped with the Rela target genes in MEFs, respectively, indicating a critical implication of RELA target genes in RELAFUS1-driven ependymoma formation (Fig. 2n, o). Interestingly, 27% of the previously reported-NF-κB target genes (n = 366) were present in the Rela-target genes (Additional file 3: Fig. S2G) [12, 41]. By contrast, only 1.1 and 4.4% of these NF-κB target genes were identified in the RELAFUS1 target genes in 293T-RELAFUS1 and H1203 cells, respectively, highlighting the importance of yet unknown- or non-NF-κB target genes in the RELAFUS-driven ependymoma formation (Additional file 3: Fig. S2H, I).

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing analyses of ependymomas identified diverse neoplastic subpopulations characterized by specific transcriptomic signatures [11, 13]. We also examined an association between the RELAFUS1 target genes and the single-cell transcriptomic signature genes of ST-ependymomas [13] and observed a significant overlap between “ST-RELA-variable” signature genes and RELAFUS1 target genes in both 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells, likely implying an important role of this subpopulation on tumorigenesis (Additional file 10: Table S2G). RELAFUS1 target genes from 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells were also found in “ST-Radial-Glia-like” and ‘ST-Metabolic’ signature genes, respectively. Taken together, these results suggest that most RELAFUS1 target genes were actively transcribed, thereby driving specific oncogenic pathways necessary for ependymoma formation in significant collaboration with the RELA/NF-κB pathway.

RELAFUS1 binds on specific DNA regions through the unique DNA-binding motif

High NF-κB activity mediated by the transcriptional activity of RELAFUS1 is thought to play a critical role in the RELAFUS1-driven ependymoma formation [41, 45]. Although some overlap between RELAFUS1 and Rela target genes were observed, non-Rela target genes were more predominantly identified among the RELAFUS1 target genes (Fig. 2n, o), implying the creation of a unique DNA-binding motif of RELAFUS1, which is independent of RELA/NF-κB regulation. Of note, the RELA/NF-κB dimer can be associated with many non-NF-κB consensus sequences [32, 67]. We thus used the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) Suite to explore what transcription factor (TF) binding motifs are enriched in RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E ChIP-seq peaks in 293T/tv-a cells (Fig. 1a–d) [1], and identified unique DNA-binding motifs, some of which were shared between them (Fig. 3a and Additional file 4: Fig. S3A). Interestingly, the canonical NF-κB consensus motif, termed as κB site (5′-GGGRNWYYCC-3′, R = A or G, N = any base, W = A or T, and Y = C or T) was not present among the top 10 motifs in either RELAFUS1 or RELAFUS1−S486E peaks (Additional file 11: Table S3A) [5, 24, 36]. In turn, when applying the TF motif analysis to Rela Peaks in MEFs [37], the NF-κB-like motif (5′-KGGAAADYCCM-3′, K = G or T, D = A or G or T, M = A or C) was identified in only 17.4% of the Rela target genes as the most enriched motif, thus confirming the presence of Rela binding on non-NF-κB consensus sequence (Additional file 4: Fig. S3B). The RELAFUS1 motifs or any related motifs were not present among the top 5 motifs in Rela peaks (Additional file 11: Table S3B).

RELAFUS1 binds on specific DNA regions through the unique DNA-binding motif. a Top three transcription factor (TF) binding motifs enriched within the RELAFUS1-HA peaks identified by the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) tool in 293T/tv-a cells. E-value, enrichment p value. b RCAS-GFP, RELA-HA, RELAFUS1-HA (FUS1-HA) and RELAFUS1−S486E-HA (4E-HA) vector expression in 293T/tv-a cells. c–e Relative Nanoluc reporter activity to the RELAFUS1-responsive element (RE) normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity and GFP cells in the 293T/tv-a cells (n = 6 or 8, in technical triplicate). MEME-1, 2 and 3 denote RELAFUS1-responsive reporters for top three (3×) or five (5×) tandem RELAFUS1-motif as shown in Additional file 4: Fig. S3D–F. f Top TF binding motif enriched within the RELAFUS1-HA peaks in mEPN cells. g, h Relative Nanoluc reporter activity to the top three tandem (3×) or top five single RELAFUS1-MEME-2 motifs normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity and GFP cells in 293T cells (n = 4 or 5, in technical triplicate). i Relative Nanoluc reporter activity to the NF-κB-RE normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity and GFP cells in 293T/tv-a cells (n = 8, in technical triplicate). Analysis was done using RM one-way ANOVA (c-e) or paired two-tailed t-test (g–i). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. j RCAS vector expression in 293T cells. C11-HA, RCAS-C11orf95-HA k Relative NFKBIA mRNA expression in 293T cells. Data (mean ± SD) are displayed as the relative ratio to GFP cells (n = 3, in technical quadruplicate). Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. l IκBα protein expression in 293T cells. See Methods for j–l

To systematically examine whether RELAFUS1 activates the gene expression via DNA-binding motifs identified by ChIP-seq, we generated luciferase reporter constructs for three RELAFUS1 motifs ranked at the top 3 and tested them in 293T/tv-a cells (Fig. 3b–e, Additional file 4: Fig. S3C-F; Additional file 11: Table S3A). We found that RELAFUS1 responded to the RELAFUS1-MEME-2 motif (5′-BGKGGCCCCBG-3′, B = C or G or T) but not to MEME-1 and 3 (Fig. 3c–e; Additional file 11: Table S3C). Further, RELAFUS1 also responded to both the triple tandem of the MEME-2 sequence ranked at 1st to 3rd in the de novo motif discovery analysis and the single MEME-2 sequence ranked within the top 4 when transiently introduced the RELAFUS1 in 293T cells (Fig. 3 g, h, Additional file 4: Fig. S3G; Additional file 11: Table S3C). Interestingly, RELAFUS1−S486E also evidently reacted to the MEME-2 motif to a somewhat lower degree compared to the RELAFUS1, whereas wild-type RELA barely responded to the MEME-2 motif (Fig. 3d). Of note, RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS1−S486E proteins were less expressed than RELA in the 293T/tv-a cells (Fig. 3b), thus emphasizing their actual activities to the MEME-2 motif. Further, when applying the TF motif analysis to mEPN cells (Fig. 2a, b), a very similar GC-rich motif (5′-CNGGGGCCACR-3′) to the 293T-RELAFUS1-MEME-2 motif was identified as the top-ranked motif (Fig. 3f; Additional file 11: Table S3D, E). These GC-rich motifs were present in 44.2 (123 out of 278 peaks) and 43.5 (194 out of 446 peaks) percent of all RELAFUS1 peaks in 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells, respectively. Again, no enrichment for the canonical NF-κB consensus motif was detected in the top 10 motifs in mEPN cells (Additional file 11: Table S3D).

To subsequently test if RELAFUS1 is able to directly activate the expression of NF-κB target genes via binding to the NF-κB consensus motif, we used a reporter construct containing the NF-κB responsive element (5 × κB sequence). As expected, expression of wild-type RELA strongly activated the reporter system and induced mRNA and protein expression of NFKBIA, a representative NF-κB target gene (Fig. 3i–l), whereas expression of RELAFUS1 only minimally activated the system (Fig. 3i). Nevertheless, forced-expression of RELAFUS1 steadily induced mRNA and protein expression of NFKBIA in a dose-dependent manner, signifying that RELAFUS1 is competent to regulate the NF-κB pathway via the consensus sequence (Fig. 3j–l, Additional file 4: Fig. S3H) [58]. In turn, RELAFUS1−S486E did not activate the reporter assay (Fig. 3i). These results suggested that RELAFUS1 might form its unique transcription network through the GC-rich MEME-2 motif in collaboration primarily with a yet unknown-NF-κB motif, rather than the consensus NF-κB motif.

C11orf95 determines the RELAFUS1-binding region through the unique GC-rich motif

The minimal response of RELA to the RELAFUS1-MEME-2 motif leads to the suggestion that the C11orf95 domain rather than RELA might be a critical determinant for the DNA binding of RELAFUS1 proteins to the MEME-2 motif (Fig. 3d). RELAFUS1-HA proteins preferentially localized in the nucleus compared to RELA-HA proteins (Fig. 4a, b) [45]. So far, C11orf95 protein function has not been described well. However, as predicted by multiple C2H2 type zinc finger domains and the putative nuclear localization signal (NLS), the C11orf95 proteins predominantly accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 4a, b) [22, 45]. Interestingly, the C11orf95 portion (C11ΔC) of the RELAFUS1 was sufficient for the nuclear localization despite the fact that the putative NLS of C11orf95 is lost, implying the presence of an additional NLS (Fig. 4a, c). We thus hypothesized that the C11ΔC portion preserving one zinc finger domain might contribute to nuclear localization and DNA-binding through the unique binding motif of RELAFUS1 proteins, thereby regulating the transcriptional activity of the target genes by the RELA’s activation domain in the RELAFUS1 protein. To reveal the molecular mechanism by which RELAFUS1 regulates the expression of specific target genes with the MEME-2 motif, we generated several C11orf95 mutants and analyzed their ability to activate the 5xMEME-2 luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 4a). The C11ΔC-NLS (CN-HA) and C11ΔC-NLS-GFP fusion (CNG-HA) were unable to activate the MEME-2 reporter, likely due to the absence of a functional activation domain (Fig. 4d, e). In turn, a construct that replaced the RELA portion of RELAFUS1 with SV40NLS-VP64, in which VP64 is a tetrameric repeat of herpes simplex VP16 minimal activation domain (C11ΔC-NLS-VP64; CNVP-HA), evidently activated the MEME-2 reporter (Fig. 4a, d, e) [2, 47]. In addition, we tested the ability of RELAFUS8 (Type 8)—a naturally occurring variant of RELAFUS, lacking most of the Rel homology domain (RHD)—as well as CRHD-HA, a RELAFUS1 mutant lacking the activation domains in the RELA portion (Fig. 4a, f) [9, 36]. RELAFUS8 strongly activated the MEME-2 reporter at levels comparable to RELAFUS1 (Fig. 4g). In turn, deletion of the RELA activation domain (CRHD-HA) resulted in the inability to activate the MEME-2 reporter (Fig. 4g). Of note, the RELAFUS8 failed to induce brain tumor formation in mice [60], thus signifying that the RHD was indispensable for the tumor-forming potential of RELAFUS1, whereas might be dispensable for the transcriptional activity via the MEME-2 motif. Taken together, these observations suggested that the C11ΔC portion primarily determined the DNA binding loci of RELAFUS1 on the MEME-2 motif. However, the cooperation of both the C11ΔC and RELA portion are essential for the regulation of the transcriptional target genes of RELAFUS1.

C11orf95 determines the RELAFUS1-binding region through the unique GC-rich motif. a Schematic of RCAS vector constructs (See Methods) b Subcellular localization of RELA-HA, C11orf95-HA and RELAFUS1-HA in DF-1 cells. c Subcellular localization of GFP and GFP-fusion proteins. DF-1 cells expressing the relevant RCAS virus were observed with fluorescent microscopy. Representative images were shown in b and c. d, f RCAS vectors expression in 293T/tv-a cells. e, g Relative Nanoluc reporter activity to the RELAFUS1-RE-luciferase (MEME-2) normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity and GFP cells in the 293T/tv-a cells expressing the indicated RCAS virus as shown in the d or f. (e, n = 6; g, n = 5 or 9 in technical triplicate) Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test (e) or RM one-way ANOVA (g). *p < 0.05

RELA FUS1 transcriptionally regulates the target gene expression through DNA binding on the RELAFUS1-MEME-2 sequence

In general, transcription factors regulate the expression of target genes in a context-dependent manner [24]. In fact, L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM), a well-known downstream marker of RELAFUS was identified as a RELAFUS1 target gene in 293T-RELAFUS1 but not in mEPN cells (Additional file 5: Fig. S4A–D) [45]. Therefore, we examined the overlap between RELAFUS1 ChIP-seq peaks in 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells (Figs. 1a, 2a). Unexpectedly, we found that only 41 genes were shared between these cells, implying a flexible DNA-binding capacity of RELAFUS as a TF function, depending on the cellular context (Fig. 5a; Additional file 9: Table S1E). However, it is noteworthy that CCND1, H-Ras, PIK3R2, and DOT1L in addition to C11orf95 were identified in the common target genes. 24 out of the 41 shared genes were located within SE regions, presumably serving as core target genes responsible for RELAFUS1-driven ependymoma formation (Figs. 2k, 5a and Additional file 5: Fig. S4E–G).

RELAFUS1 transcriptionally regulates the target gene expression through DNA binding on the RELAFUS1-MEME-2 sequence. a Venn diagram showing the number of the RELAFUS1 target genes overlapped between 293T and mEPN cells. 41 common targets were shown in the right table. SE-located genes were highlighted in yellow. b, c, i, j RELAFUS1-HA, RELAFUS1−S486E-HA and H3K27ac binding profiles surrounding the human C11orf95 and LMX1B in 293T/tv-a, and mouse 2700081O15Rik and Lmx1b loci in mEPN (H1203 and H41) cells. Rela binding profile in MEFs was also shown in mouse 2700081O15Rik locus. The position of the MEME-2 and κB sites are shown as a blue vertical bar on positive (+) and negative (−) DNA strands. d Boxplots of C11orf95 and LMX1B mRNA expression in human RELAFUS positive (n = 14) and negative (n = 54) ependymomas. e, f Boxplots of 2700081O15Rik and Lmx1b mRNA expression in mouse normal brain (NB) and RCAS-RELAFUS1-driven ependymoma or PDGFA-driven glioma tissues in the N/tv-a (e) or N/tv-a;Ink4a-Arf−/−;Ptenfl/fl (KO) (f) mice (n = 4 in each group). All box plots showing mRNA expression extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. Whiskers of the box plots extend to the most extreme data point (d–f). Gene expression analysis was done using unpaired two-tailed t-test (d, e) or Ordinary one-way ANOVA (f). **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. g Relative C11orf95 and LMX1B mRNA expression in 293T cells. Data are displayed as the relative ratio to GFP cells. qPCR data (mean ± SD) for C11orf95 and LMX1B expression are displayed as the relative ratio to GFP cells (n = 3, in technical quadruplicate). Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (See Methods). h Relative Nanoluc reporter activity to the upstream sequence of C11orf95 gene normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity and GFP cells in the 293T cells (n = 6, in technical triplicate). Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test. ****p < 0.0001 k Relative Lmx1b mRNA expression in H1203 cells introduced with the indicated dCas-sgRNA. Data are displayed as the relative ratio to sgGFP vector-infected cells. Data from two independent experiments with two technical replicates are shown in the figures. Each qPCR was performed in technical quadruplicate. Analysis was done using paired two-tailed t-test. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The fact that C11orf95 was a RELAFUS1 target in both cell types provides significant insights into the understanding of the oncogenic mechanism of RELAFUS1. Prominent peaks of RELAFUS1 binding were detected around the TSS within both the C11orf95 and 2700081O15Rik loci in the HA ChIP-seq analyses (Fig. 5b, c). Interestingly, multiple MEME-2 sites were concomitantly found in the RELAFUS1 peaks, thus strongly suggesting a direct transcriptional regulation of C11orf95 gene expression by RELAFUS1 (Fig. 5b, c). Indeed, human RELAFUS ependymomas exhibited significantly higher C11orf95 mRNA expression than negative ones (Fig. 1e, 5d and Additional file 2: Fig. S1F). Further, as bolstered by the overlapping of H3K27ac peaks with the RELAFUS1 peaks in the 2700081O15Rik gene (Fig. 5c), 2700081O15Rik was remarkably up-regulated in RELAFUS1-driven ependymomas relative to normal brains and PDGFA-driven gliomas (Fig. 5e, f). Forced-expression of RELAFUS1 in 293T cells was able to induce C11orf95 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3j, 5g). Further, to confirm if RELAFUS1 had a direct impact on the C11orf95 expression, we cloned an immediate upstream sequence of the C11orf95 gene, including three MEME-2 motifs into a luciferase reporter vector (Additional file 4: Fig. S3C, Additional file 6: Fig. S5A). We found that the expression of RELAFUS1 strongly activated this reporter, suggesting that RELAFUS1 is able to up-regulate its own expression directly (Fig. 5h). Since RELAFUS is caused by the genomic rearrangement involving C11orf95 and RELA loci [45], the expression of the RELAFUS gene is thought to be controlled by the C11orf95 promoter, thus possibly resulting in the formation of an autoregulatory feedback loop in the tumors (Additional file 6: Fig. S5B). Of note, 2700081O15Rik was found to be a direct Rela target gene, as shown by a Rela peak with multiple κB sites in the gene locus, which are different from MEME-2 sites (Fig. 5c; Additional file 9: Table S1E). However, the lack of RELAFUS1 binding to the κB sites suggests a specific 2700081O15Rik gene regulation by RELAFUS independent of Rela.

The distribution of RELAFUS1 binding loci in our ChIP-seq analyses suggests that RELAFUS1 might also control the gene expression via an intronic enhancer regulatory region. Thus, to further investigate the TF function of RELAFUS1, we focused on the LMX1B gene, a brain-developmental transcription factor, which was one of the common RELAFUS1 target genes in 293T-RELAFUS1 and mouse ependymoma cells and was also selected as one of the enhancer-associated genes specific for human RELAFUS tumors and mouse ependymoma cells (Fig. 2k, 5a) [31]. RELAFUS1 bound similar positions on the LMX1B gene locus in 293T and mouse ependymoma cells. Two RELAFUS1 peaks containing the MEME-2 motif were found in the putative promoter region (upstream of the TSS) and second long intron of both human and mouse genes (Fig. 5i, j). The H3K27ac peaks were also concomitantly identified in these loci in mEPN cells, suggesting the direct gene regulation by RELAFUS1 (Fig. 5j). As expected, a significant upregulation of LMX1B was observed in both human and mouse RELAFUS tumors (Fig. 1e, 5d–f). Further, forced-expression of RELAFUS1 in 293T cells was able to induce LMX1B expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3j, 5g). Interestingly, GeneHancer profiling indicated an association between the promoter and enhancer regulatory elements in the second intron of the human LMX1B gene (Additional file 6: Fig. S5C) [8]. Therefore, to dissect a mechanism of LMX1B gene regulation by RELAFUS1, we examined if physical perturbation of RELAFUS1 binding on these loci affected the gene expression using the CRISPR-dCas9 system [49]. We designed multiple sgRNAs to target the CRISPR-dCAS9-sgRNA complexes in two regions around the MEME-2 motif denoted as Region-1 and -2 (R1 and R2), and then lentivirally introduced them in mEPN cells (Fig. 5j, Additional file 6: Fig. S5D-F). Targeting R1 (intronic region) but not R2 (promoter region) resulted in significant downregulation of Lmx1b gene expression (Fig. 5k, Additional file 6: Fig. S5G). Collectively, these findings appear to represent prototypic examples for epigenetic gene regulation of RELAFUS1, thus confirming the oncogenic TF function of RELAFUS1 on the MEME-2 sequence.

Anti-cancer drug screening highlights oncogenic signaling driven by RELAFUS1 target genes

We finally used Gene Ontology (GO) analysis based on our ChIP-seq experiments to explore the signaling network directly regulated by RELAFUS1 target genes. As expected by the small number of RELAFUS1 target genes shared between 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells, diverse signaling networks were enriched in these cells with a little overlap between both cell types (Fig. 5a, 6a, b) [3]. Target genes of the 293T-RELAFUS1 were notably involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells, VEGF signaling, and Regulation of PTEN gene transcription (Fig. 6a; Additional file 12: Table S4A). On the other hand, GO terms enriched in mEPN cells converged to Glioma, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Signaling by PDGF, VEGF signaling pathway, RNA Polymerase II Transcription, Protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, and non-integrin membrane-ECM interactions (Fig. 6b; Additional file 12: Table S4B). Target genes of 293T-RELAFUS1−S483E presented somewhat different signaling pathways from those of 293T-RELAFUS1 as suggested by the number of target genes shared between these cells, presumably due to an impairment of DNA and/or protein binding due to the mutation in the RHD (Fig. 1g, h, 6a, Additional file 7: Fig. S6A, Additional file 12: Table S4A, C). Interestingly, when focusing on common pathways between the 293T-RELAFUS1 and mEPN cells, we identified an enrichment of ‘Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs)’, particularly VEGF signaling (Fig. 6c). Association of aberrant RTK activity, such as EFN, PDGF, and FGFR signaling, with ependymomagenesis was previously reported [19, 31, 41, 44] and thereby implicated as potential therapeutic targets for this tumor type (Additional file 7: Fig. S6B, C, Additional file 12: Table S4D-G). Further, PDGF signaling was found to be a direct transcriptional target of RELAFUS1 in mEPN cells (Additional file 7: Fig. S6D), consistent with previous observations that PDGF signaling was up-regulated in human and mouse RELAFUS1 tumors [41, 44, 45]. Therefore, to examine if blockade of these signaling pathways had a significant inhibitory effect on the tumor growth, we performed an anti-cancer drug screening using the FDA-approved drug library with additional selected-NF-κB inhibitors in two mEPN cells (Additional file 3: Fig. S2A; Additional file 13: Table S5A) [40]. We treated the cells with these drugs and focused on drugs presented over 85% growth inhibition (Fig. 6d, e, Additional file 8: Fig. S6E; Additional file 13: Table S5B). As expected, multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as Sorafenib (targeting VEGFR, PDGFR and RAF) and Ponatinib (targeting BCR-ABL, Src, VEGFR, FGFR, and PDGFR) were able to effectively inhibit the growth of these cells (Fig. 6e; Additional file 13: Table S5B) [38, 66]. Interestingly, in addition to an IκB kinase inhibitor (IKK-16), HDAC inhibitors (Belinostat, Romidepsin, Vorinostat) and a Proteasome inhibitor (Bortezomib), both of which were known to block NF-κB signaling were able to effectively inhibit the growth of mEPN cells, likely supporting the contribution of NF-κB activity in RELAFUS1 ependymomas [26, 33, 62]. We then determined the half-maximal inhibitory concentration values (IC50) of these drugs and selected six representatives from these drug categories. The IC50 values of these drugs were very similar between both mEPN cells, indicating the high specificity of these inhibitors to RELAFUS1 (Fig. 6f, g). These results suggest that inhibitors against NF-κB and RTK signaling (most notably drugs targeting VEGFR and PDGFR) could be promising therapeutic agents for RELAFUS tumors.

Anti-cancer drug screening highlights oncogenic signaling driven by RELAFUS1 target genes. a, b Pathway enrichment analysis for RELAFUS1 target genes in 293T-RELAFUS1 (a) and H1203-mEPN (b) cells. Color nodes and the size represent the enriched gene set and the number of genes in each gene set, respectively. c Venn diagram showing the number of the overlapping of pathways involved with the 293T-RELAFUS1, 293T-RELAFUS1−S486E, and H1203-RELAFUS1 target genes. Common GO term of dysregulated pathways driven by RELAFUS1 target genes within the TSS ± 10 kb in 293T-RELAFUS1 and H1203 cells is shown in the right panel. d Correlation of cell viability in two mEPN cells (H41 and H1203). Cells were treated with 179 anti-cancer drugs with 10 μM for 72 h in two technical replicates. The mean values of two independent experiments for each cells are shown in x and y axis, respectively. Analysis was done using two-tailed Pearson's correlation. e List of twenty drugs presented over 85% growth inhibition relative to the 0.1% DMSO-treated control. The mean values of cell viability in H41 and H1203 cells are shown in the figure. f, g Cell viability of mEPN cells (f H41 and g H1203 cells) treated with six selected drugs. The IC50 values of each anti-cancer drug were shown in the figures

Discussion

In this study, we performed ChIP-seq experiments to explore target genes that are directly regulated by RELAFUS1 and unveiled the unique epigenetic regulation of RELAFUS in ependymoma formation (Additional file 8: Fig. S6F). Activation of the NF-κB pathway has been so far well-documented in human and mouse RELAFUS ependymomas [41, 45]. However, it remained to be determined how this pathway contributes to tumorigenesis and if it might serve as an actual therapeutic target in patients. Our findings suggest that RELAFUS1 might induce brain tumor formation through two main oncogenic pathways regulated by C11orf95 and RELA target genes (Additional file 8: Fig. S6F). The NF-κB pathway driven by the RELA portion was essential for tumorigenesis, although unknown-RELA/NF-κB target pathways were likely more common than canonical pathways via the κB site. Thus, blockade of active NF-κB pathways will likely be one option for RELAFUS-positive ependymoma therapy.

RELA regulates NF-κB target genes by forming homo- or heterodimers, and the selectivity of the NF-κB response is variable according to the dimerization partner [23, 57]. Of note, the RELA/NF-κB dimer can interact with both NF-κB consensus motif and many non-consensus sequences [32, 67]. It is not known whether RELAFUS forms dimers or if the dimerization is necessary for tumorigenesis. However, our reporter assays with the MEME-2 and NF-κB motifs and the absence of the κB site in the DNA sequences bound by RELAFUS1 indicate that DNA binding of RELAFUS1 might have deviated from that of RELA, thus suggesting unusual dimerization of RELAFUS1.

The RELAFUS1−S486E mutant remarkably responded to the MEME-2 motif but completely failed to recognize the κB site. Phosphorylation of S276 in the RHD by PKAc induces the conformation change of RELA and subsequent recruitment of p300/CBP, thereby resulting in promoting the transcriptional activity [71]. Thus, severe impairment of the oncogenicity of the mutant might be explained by the inability to exert a precise conformation change, consequently losing the capacity to activate the NF-κB pathway. Similarly, the RELAFUS8 variant, which is lacking the RHD, was capable of recognizing the MEME-2 motif and displayed prominent transcriptional activity but failed to induce brain tumors [60]. These observations support that both RELA/NF-κB activity and binding to the MEME-2 motif on its own is insufficient but essential for the tumor-forming potential of RELAFUS1.

We observed RELAFUS1 binding peaks concomitant with MEME-2 sequences, which is recognized by the C11orf95 portion of RELAFUS1,within the regulatory regions of RELAFUS1 target genes. The RELA subunit preferentially binds to a DNA sequence consisting of a series of G bases at the 5′ position followed by a central A/T base for fine transcriptional regulation [10, 36, 63]. Therefore, the absence of the central A/T bases, characteristic for the consensus NF-κB motif sequence, in the MEME-2 motif strongly suggests that transcriptional regulation of these C11orf95 target genes by RELAFUS1 was independent of gene regulation via the consensus NF-κB motif [63]. Interestingly, we have recently shown that RELAFUS variants with one C2H2 type zinc finger domain in the C11orf95 portion (RELAFUS1 and RELAFUS4) presented a more aggressive phenotype compared to those with two zinc finger domains (RELAFUS2 and RELAFUS3), supporting the importance of the RELAFUS function via the C2H2 type zinc finger domain [60]. Taken together, these observations suggested that two independent programs driven by C11orf95 and RELA target genes are likely central players in the tumorigenic functions of RELAFUS.

Our anti-cancer drug screening highlighted several compounds targeting signaling pathways associated with the oncogenic mechanisms of RELAFUS1, such as RTK, HDAC and NF-κB inhibitors including a proteasome inhibitor. Interestingly, Actinomycin D, previously identified as a potential drug for RELAFUS tumors, was also selected in the top-ranked drugs, thus supporting a specificity of our screening to the RELAFUS [61]. Further, a Phase II Clinical Trial of Marizomib, a second-generation irreversible proteasome inhibitor is currently ongoing for “Recurrent Low-Grade and Anaplastic Supratentorial, Infratentorial and Spinal Cord Ependymoma” (NCT03727841). The therapeutic effect is predicted especially against RELAFUS tumors. However, it is of note that such a screening is generally biased toward identifying cytotoxic agents, as also demonstrated by our screening. Thus, a more careful selection would be essential for precisely evaluating the specificity of compounds.

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the RELAFUS-driven ependymoma formation is increasingly deepened by recent key reports [31, 72]. In this study, we not only successfully reproduced many of the data shown in the previous studies but also presented a more detailed functional analysis of RELAFUS in several aspects [31, 72]. Our analyses similarly identified L1CAM, IGF2, C11orf95, DOT1L, CCND1 and RELA genes as direct RELAFUS targets that contain the specific RELAFUS binding motif. Further, we experimentally demonstrated the transcriptional regulation of target genes by RELAFUS and highlighted a potential autoregulatory feedback loop by RELAFUS of itself in these tumors. Interestingly, several RELAFUS target genes such as L1CAM and IGF2 were not necessarily common in 293T and mouse ependymoma cells in our analyses, indicating the fact that the transcriptional programs activated by RELAFUS are context-dependent. Thus, our study emphasizes the significance to examine TF functions in various experimental settings. In contrast to gene fusions involving protein kinases, such as the BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia [21], therapeutic targets for cancers harboring gene fusion involving transcription factors are more elusive owed to their complex functions, as shown in this study. Therefore, our experimental approach integrating with ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, functional studies, and drug screenings will be helpful for not only a better understanding of ependymoma biology but also the identification of the precise therapeutic targets. Ependymomas are still lethal brain tumors, and hopefully, the results of this study will greatly contribute to the advancement of ependymoma research.

Conclusions

So far, the contribution of the C11orf95 moiety to RELAFUS-driven ependymoma formation has been considerably underestimated. Our study revealed that the C11orf95 moiety was a key determinator for the nuclear localization and DNA binding of RELAFUS, consequently forming the complex oncogenic signaling networks in significant collaboration with the RELA targets. These findings will provide therapeutic insights for patients with RELAFUS positive ependymoma.

Data availability

ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) with the accession numbers DRA010686.

Code availability

All codes in this study are available upon request.

Change history

27 May 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01157-y

Abbreviations

- RELAFUS :

-

C11orf95-RELA fusion

- RELAFUS1 :

-

C11orf95-RELA type 1 fusion

- mEPN:

-

mouse ependymoma

- SE:

-

super-enhancer

- ST-EPN:

-

supratentorial ependymoma

- TF:

-

transcription factor

- TSS:

-

transcription start site

References

Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS (2009) MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W202-208. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp335

Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Dreier B, Barbas CF 3rd (1998) Toward controlling gene expression at will: specific regulation of the erbB-2/HER-2 promoter by using polydactyl zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:14628–14633. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.25.14628

Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman WH, Pages F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J (2009) ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 25:1091–1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101

Charles N, Ozawa T, Squatrito M, Bleau AM, Brennan CW, Hambardzumyan D, Holland EC (2010) Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.001

Chen FE, Ghosh G (1999) Regulation of DNA binding by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors: structural views. Oncogene 18:6845–6852. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1203224

DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M (2012) NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev 246:379–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x

Downing JR, Wilson RK, Zhang J, Mardis ER, Pui CH, Ding L, Ley TJ, Evans WE (2012) The pediatric cancer genome project. Nat Genet 44:619–622. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2287

Fishilevich S, Nudel R, Rappaport N, Hadar R, Plaschkes I, Iny Stein T, Rosen N, Kohn A, Twik M, Safran M et al (2017) GeneHancer: genome-wide integration of enhancers and target genes in GeneCards. Database (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bax028

Fukuoka K, Kanemura Y, Shofuda T, Fukushima S, Yamashita S, Narushima D, Kato M, Honda-Kitahara M, Ichikawa H, Kohno T et al (2018) Significance of molecular classification of ependymomas: C11orf95-RELA fusion-negative supratentorial ependymomas are a heterogeneous group of tumors. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6:134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0630-1

Ghosh G, Wang VY, Huang DB, Fusco A (2012) NF-kappaB regulation: lessons from structures. Immunol Rev 246:36–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01097.x

Gillen AE, Riemondy KA, Amani V, Griesinger AM, Gilani A, Venkataraman S, Madhavan K, Prince E, Sanford B, Hankinson TC et al (2020) Single-cell RNA sequencing of childhood ependymoma reveals neoplastic cell subpopulations that impact molecular classification and etiology. Cell Rep 32:108023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108023

Gilmore TD Retrieved from http://www.bu.edu/nf-kb/gene-resources/target-genes/

Gojo J, Englinger B, Jiang L, Hubner JM, Shaw ML, Hack OA, Madlener S, Kirchhofer D, Liu I, Pyrdol J et al (2020) Single-cell RNA-seq reveals cellular hierarchies and impaired developmental trajectories in pediatric ependymoma. Cancer Cell 38(44–59):e49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.06.004

Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, Pestell RG, Baldwin AS Jr (1999) NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol 19:5785–5799. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785

Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, Heder A, Scheidereit C, Strauss M (1999) NF-kappaB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol 19:2690–2698. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.19.4.2690

Holland EC, Celestino J, Dai C, Schaefer L, Sawaya RE, Fuller GN (2000) Combined activation of Ras and Akt in neural progenitors induces glioblastoma formation in mice. Nat Genet 25:55–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/75596

Holland EC, Hively WP, DePinho RA, Varmus HE (1998) A constitutively active epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with disruption of G1 cell-cycle arrest pathways to induce glioma-like lesions in mice. Genes Dev 12:3675–3685

Holland EC, Varmus HE (1998) Basic fibroblast growth factor induces cell migration and proliferation after glia-specific gene transfer in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:1218–1223

Johnson RA, Wright KD, Poppleton H, Mohankumar KM, Finkelstein D, Pounds SB, Rand V, Leary SE, White E, Eden C et al (2010) Cross-species genomics matches driver mutations and cell compartments to model ependymoma. Nature 466:632–636. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09173

Kaneko S, Son J, Shen SS, Reinberg D, Bonasio R (2013) PRC2 binds active promoters and contacts nascent RNAs in embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:1258–1264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2700

Kantarjian H, Sawyers C, Hochhaus A, Guilhot F, Schiffer C, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Niederwieser D, Resta D, Capdeville R, Zoellner U et al (2002) Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med 346:645–652. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011573

Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H (2009) Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:10171–10176. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900604106

Kunsch C, Ruben SM, Rosen CA (1992) Selection of optimal kappa B/Rel DNA-binding motifs: interaction of both subunits of NF-kappa B with DNA is required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol 12:4412–4421. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.12.10.4412

Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR, Weirauch MT (2018) The human transcription factors. Cell 172:650–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029

Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923

Leus NG, Zwinderman MR, Dekker FJ (2016) Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC 3) as emerging drug target in NF-kappaB-mediated inflammation. Curr Opin Chem Biol 33:160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.06.019

Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W (2014) featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30:923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656

Liu W, Xie Y, Ma J, Luo X, Nie P, Zuo Z, Lahrmann U, Zhao Q, Zheng Y, Zhao Y et al (2015) IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics 31:3359–3361. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv362

Loven J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, Bradner JE, Lee TI, Young RA (2013) Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 153:320–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036

Machanick P, Bailey TL (2011) MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 27:1696–1697. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189

Mack SC, Pajtler KW, Chavez L, Okonechnikov K, Bertrand KC, Wang X, Erkek S, Federation A, Song A, Lee C et al (2018) Therapeutic targeting of ependymoma as informed by oncogenic enhancer profiling. Nature 553:101–105. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25169

Martone R, Euskirchen G, Bertone P, Hartman S, Royce TE, Luscombe NM, Rinn JL, Nelson FK, Miller P, Gerstein M et al (2003) Distribution of NF-kappaB-binding sites across human chromosome 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:12247–12252. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2135255100

McConkey DJ, Zhu K (2008) Mechanisms of proteasome inhibitor action and resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat 11:164–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2008.08.002

Merchant TE, Bendel AE, Sabin ND, Burger PC, Shaw DW, Chang E, Wu S, Zhou T, Eisenstat DD, Foreman NK et al (2019) Conformal radiation therapy for pediatric ependymoma, chemotherapy for incompletely resected ependymoma, and observation for completely resected, supratentorial ependymoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 37:974–983. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01765

Mohankumar KM, Currle DS, White E, Boulos N, Dapper J, Eden C, Nimmervoll B, Thiruvenkatam R, Connelly M, Kranenburg TA et al (2015) An in vivo screen identifies ependymoma oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes. Nat Genet 47:878–887. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3323

Mulero MC, Wang VY, Huxford T, Ghosh G (2019) Genome reading by the NF-kappaB transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 47:9967–9989. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz739

Ngo KA, Kishimoto K, Davis-Turak J, Pimplaskar A, Cheng Z, Spreafico R, Chen EY, Tam A, Ghosh G, Mitchell S et al (2020) Dissecting the regulatory strategies of NF-kappaB RelA target genes in the inflammatory response reveals differential transactivation logics. Cell Rep 30(2758–2775):e2756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.108

O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, Adrian LT, Zhou T, Huang WS, Xu Q et al (2009) AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell 16:401–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, Patil N, Waite K, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2019) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol 21:v1–v100. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noz150

Oyama R, Takahashi M, Yoshida A, Sakumoto M, Takai Y, Kito F, Shiozawa K, Qiao Z, Arai Y, Shibata T et al (2017) Generation of novel patient-derived CIC- DUX4 sarcoma xenografts and cell lines. Sci Rep 7:4712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04967-0

Ozawa T, Arora S, Szulzewsky F, Juric-Sekhar G, Miyajima Y, Bolouri H, Yasui Y, Barber J, Kupp R, Dalton J et al (2018) A De Novo mouse model of C11orf95-RELA fusion-driven ependymoma identifies driver functions in addition to NF-kappaB. Cell Rep 23:3787–3797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.099

Ozawa T, Riester M, Cheng YK, Huse JT, Squatrito M, Helmy K, Charles N, Michor F, Holland EC (2014) Most human non-GCIMP glioblastoma subtypes evolve from a common proneural-like precursor glioma. Cancer Cell 26:288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2014.06.005

Pajtler KW, Mack SC, Ramaswamy V, Smith CA, Witt H, Smith A, Hansford JR, von Hoff K, Wright KD, Hwang E et al (2017) The current consensus on the clinical management of intracranial ependymoma and its distinct molecular variants. Acta Neuropathol 133:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1643-0

Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, Wani K, Tatevossian R, Punchihewa C, Johann P et al (2015) Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across All CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell 27:728–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.002

Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, Lee R, Tatevossian RG, Phoenix TN, Thiruvenkatam R et al (2014) C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature 506:451–455. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13109

Pennacchio LA, Bickmore W, Dean A, Nobrega MA, Bejerano G (2013) Enhancers: five essential questions. Nat Rev Genet 14:288–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3458

Perez-Pinera P, Kocak DD, Vockley CM, Adler AF, Kabadi AM, Polstein LR, Thakore PI, Glass KA, Ousterout DG, Leong KW et al (2013) RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods 10:973–976. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2600