Abstract

Background

Delay in commencing insulin among type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) patients is common. One of the reasons is patients' psychological insulin resistance, which is particularly prevalent in Chinese patients. This study examined the correlation between socio-demographic and clinical characteristics; and attitudes towards commencing insulin in Chinese primary care patients.

Method

A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 303 insulin-naïve Type 2 DM patients recruited from 15 primary care clinics across Hong Kong using the Chinese Attitudes to Starting Insulin Questionnaire (Ch-ASIQ). Subject selection criteria were patients on maximal oral anti-diabetes treatment who needed to commence insulin therapy. Linear regression was used to identify correlations between age, sex, educational level, occupation, body mass index, diabetes disease duration, laboratory test indicating disease control and biochemical markers including glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level, low density lipoprotein level and estimated glomeruli filtration rate, and presence of diabetic complications with the four sub-scales (self-image and stigmatization; factors promoting self-efficacy; fear of pain or needles; time and family support ) and the overall Ch-ASIQ score.

Results

The most prevalent negative attitude was ‘fear of needle injections’ (70.1 %). The most common positive attitude was ‘I can manage the skill of injecting insulin’ (67.5 %). The mean Ch-ASIQ score of 2.50 (S.D. = 0.38) was equal to the mid-score, which signified an overall ambivalent attitude among the study population. Women scored significantly higher in the fear of pain or needles subscale (p = 0.011) and had an overall more negative attitude towards commencing insulin (p = 0.016). Subjects with lower HbA1c levels also had a significantly lower Ch-ASIQ sum score (p = 0.048) indicating a more negative attitude towards commencing insulin.

Conclusion

In Chinese primary care patients with Type 2 DM, the need to commence insulin was associated with a number of negative emotions, which lead to a lower motivation to accept treatment. Perception of need as indicated by HbA1c level may be an important influencing factor determining a patient’s overall attitude towards starting insulin. Fortunately, in our setting, the injection technique does not appear to be a major barrier. However, needle fears are common, especially amongst women. Target interventions to acknowledge and help them to overcome their fears are essential before insulin treatment is commenced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Current guidelines recommend that insulin treatment should be initiated as early as possible in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) who fail to achieve adequate glycemic control on oral drugs only, as early initiation of insulin has been shown to improve outcomes [1]. Delays in commencing insulin are commonly observed in studies conducted in the United States and the United Kingdom [2, 3], which have been shown to result in higher risks of DM complications [4]. Previous studies have identified that the reasons for delay are often related to psychological, cognitive and physical barriers from the perspectives of both patients and their physicians [5]. Patients’ reluctance to initiate insulin, termed ‘Psychological Insulin Resistance’ (PIR) [6] is an area of interest to researchers because health care professionals need to be informed on how to assist patients to overcome their barriers. There is evidence of ethnic differences in the reasons behind the resistance to starting insulin [7]. In Asia, and in particular Chinese patients with DM, a higher fear of injection and a greater perception of hardship towards using insulin was observed when compared with patients in Western settings [8, 9]. Women and patients with lower education levels have also been identified as having greater PIR [10].

Worldwide, as the prevalence of Type 2 DM increases, the number of patients needing to commence insulin is foreseeably going to rise [11]. Health care professionals will start to encounter more and more patients with PIR, and there will be a need for more evidence-based strategies on how to help patients overcoming their barriers to commencing insulin.

The predictors and factors associated with specific key attitudes towards insulin can inform the development of evidence-based interventions, to help patients to overcome their PIR and enhance acceptance to initiate insulin [12]. Therefore, this study aimed at exploring the relationship between socio-demographics and clinical characteristics (as indicated by their laboratory results and presence of diabetic complications), and attitudes towards commencing insulin in type 2 DM patients requiring insulin [13].

Methods

Participants

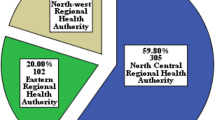

Subjects were recruited from 15 government-funded primary care general outpatient clinics (GOPCs) located in Kowloon, New Territories and Lantau Island of Hong Kong. Clinic nurses and doctors identified all eligible Chinese-speaking DM patients using the computerized laboratory result enquiry system and the drug dispensing system from July 2011 to March 2013. Inclusion criteria included: age between 18 and 80 years; on maximum recommended dosage of oral anti-diabetes treatment OADs (defined by either on Gliclazide 320 mg, Gliclazide modified release 120 mg, Glibenclamide 15 mg or metformin ≥2 g daily or Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors or alpha glucosidase inhibitor); and the most recent HbA1c level ≥7.5 % (58.5 mmol/mol) within past 12 months indicating insufficient glycaemic control [1, 14]. Subjects who were pregnant, or unable to answer a questionnaire due to mental incapacity, or who had already commenced on insulin were excluded.

Data collection

All eligible subjects were flagged in the computerized appointment system before their scheduled clinic appointment. Following the medical consultation with the GOPC doctor, the targeted subjects were approached by trained research assistants (RAs) who explained the study, obtained signed informed consent, and distributed the study questionnaire. Participants were encouraged to self-administer the traditional Chinese questionnaire as far as possible. However, as a large proportion of the patients attending the GOPCs are elderly and have poor literacy or eyesight, the RAs helped to administer the questionnaires using local Cantonese to those who were unable to complete the questionnaire by themselves.

Questionnaires

A locally validated instrument, the 13-item Chinese Attitudes to Starting Insulin Questionnaire (Ch-ASIQ) was used to assess patients’ attitudes to starting insulin. The psychometric properties of the Ch-ASIQ have been evaluated and found to have four sub-scales consisting of 3 items related to ‘Self-image and stigmatization’; 5 items related to ‘Factors promoting self-efficacy; 3 items related to ‘Fear of pain or needles’; and 2 items related to ‘Time and family support’ (Appendix) [13]. Responses to each item are scored using a 4-point Likert scale (Totally disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Agree = 3; Totally Agree = 4). Individual scale scores are calculated by summing of the item responses. For two of the subscales ‘Factors promoting self-efficacy’ and ‘Time and family support’, higher scores indicates more positive attitudes towards the use of insulin. For the other two subscales ‘Self-image and stigmatization’ and ‘Fear of pain or needles’ a higher score indicates a more negative attitude towards insulin initiation. The weighted sum of all four scale scores, converting two positively coded scales to negatively coded scales, calculates the Ch-ASIQ overall score with higher scores indicating more negative attitude to starting insulin. All subscale and overall scores range from 1 to 4, with a mid-point of score 2.5. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four factors were above 0.60 (0.62–0.80). It is the first psychometric validated questionnaire on barriers to starting insulin for diabetic patients in the primary care setting [13].

DM complications assessment

All Type 2 DM patients who attend the GOPC undergo routine laboratory tests, retinal photo or ophthalmologist assessment and nurse-led diabetes complication screening clinics under the Risk Factor Assessment & Management Programme (RAMP) [15, 16] which is conducted once every 1–2 years as part of their usual chronic disease managed care. Plasma glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; ml min−11.73 m−2) by Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Formula, lipid profile (including low density lipoprotein LDL; mmol/L), urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; mg/mmol) were assessed in associated hospital or Department of Health Central Laboratories. Presence of foot ulcers and DM neuropathy (by using 10-g monofilament plus testing vibration perception threshold) were assessed by trained GOPC nurses. Presence of diabetic retinopathy diagnosis was confirmed either by registered optometrist, ophthalmologist or GOPC physicians. Presence of DM complications, physician diagnosis of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke, all the biomedical and socio-demographic data were reviewed via the Hospital Authority’s computerized patient records.

Ethics

The Research Ethics Committee of the Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority of Hong Kong granted research ethics approval of the research protocol.

Statistical analysis

From the power analysis with a sample size of 303 patients recruited in this study, a 99.8 % power was achieved to detect an R-square of 0.126 attributed to 13 independent variables using an F-test with a significance level of 0.05. Hence, the sample size retained the sufficiently high power for regression analysis.

Descriptive statistics were calculated with median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, and frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Proportions of patients giving choices of “Agree” or “Totally Agree” for each item of Ch-ASIQ were calculated. Mean and standard deviation of 13 individual item scores and 4 scale scores were shown. Linear regressions were performed to explore the associations of scale scores and overall score of Ch-ASIQ with patients’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 statistical software was used to conduct descriptive and linear regression analyses.

Results

Of the 306 potential subjects approached, three refused to participate (response rate =99.0 %). The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Typical of the patient population attending government-funded primary care clinics, these subjects were elderly (median age 63, interquartile range (IQR) = 54–70), had lower levels of educational attainment (56.5 % primary or below), and only one third were in full-time employment.

The median duration of Type 2 DM was 11 years (IQR = 7 to 16 years) and median HbA1c level was 8.3 % (67.2 mmol/mol) [IQR = 7.9 % (62.8 mmol/mol) to 9.1 % (76.0 mmol/mol)] indicating overall very poor level of glycemic control. Most subjects (94.7 %) were on two kinds of OADs (combination of metformin with another sulphonylurea) while 1.3 % were on monotherapy and 4 % were on 3 kinds of OADs (combination of metformin with sulphonylurea and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors or alpha glucosidase inhibitor). Seventy-two percent of them were either obese (54.2 %) or overweight (17.4 %). Most of them (81.2 %) had concomitant hypertension, while few subjects had coexisting stroke (4.8 %) and ischemic heart disease (1.7 %). Their LDL level (median = 2.5 mmol/L,IQR 2.0–3.0) and estimated glomerular filtration rate eGFR (median =88.0 ml/min/1.73 m2, IQR 70.5–108.0) were overall clinically optimal. The most common DM complication in this population was retinopathy (57.5 %), followed by nephropathy (16.8 %) and neuropathy (2.0 %).

Descriptive statistics of the 13 items and overall score of Ch-ASIQ are shown in Table 2. Due to missing values, 8 (2.6 %), 30 (9.9 %), 10 (3.3 %), 18 (5.9 %), and 41 (13.5 %) patients were excluded from the analysis of scale 1, scale 2, scale 3, scale 4 and the overall Ch-ASIQ score, respectively. Mean scores for each subscale were calculated. Higher mean subscale scores in scale 1 (self-image and stigmatization) and scale 3 (fear of pain or needles) showed more negative attitudes towards insulin, whilst higher mean subscale scores in scale 2 (factors promoting self-efficacy) and scale 4 (Time & family support) showed more positive attitudes. The overall Ch-ASIQ scored 2.50 (S.D. 0.38) which was the mid-point score. It indicated overall ambivalence to starting insulin. The highest three negative attitudes regarding starting insulin were “I am afraid of needle injection” (70.6 %), followed by “injecting insulin is painful” (66.9 %), and “There is no social support available if I have to inject insulin” (55.6 %). The highest three positive attitudes towards starting insulin all belonged to scale 2: the factors promoting self-efficacy: “I can manage the skill of injecting insulin” (67.5 %); followed by “I can pay as close attention to my diet as my insulin treatment required” (66.7 %); and “insulin can help control blood glucose and prevent complications” (63.7 %).

Results of the linear regression analysis showing the factors and the scores of Ch-ASIQ are shown in Table 3. More negative attitudes to starting insulin were found in women (p = 0.01 6). Being female accounted for 16.4 % of variance of the negative attitude towards insulin. While the most significant factors among women was fear of pain or needles (p = 0.011), which accounted for 26.2 % of the variance of the negative attitude. Interviewer administered subjects had lower self-efficacy when compared with self-administered subjects. Subjects with lower HbA1c levels had significantly higher barriers to starting insulin. Subjects on larger number of OADs had more factors promoting self-efficacy for insulin therapy (p = 0.04) including: better up-to-date knowledge (item#4);better social support for insulin treatment (item#7); higherbelief that insulin can help control blood sugar (item#5); better confidence that they can manage the skill of injecting insulin (item#6) and diet control (item#8). Age, education level, working status, duration of DM, coexisting hypertension and complicated with retinopathy showed no significant differences in the overall scores and subscales of Ch-ASIQ.

Discussion

The study population characteristics showed that they were representative of the type 2 DM patients attending GOPCs in Hong Kong [17]. Despite their overall older age 63 (IQR: 54–70) and low education level (56.5 % attained primary education or below), more than 65 % of them believed that they could manage theinjection skill and diet modifications associated with insulin treatment (item #6 & #8) (Appendix), which had been found to be a barrier to insulin in previous studies [18]. These positive attitudes could be acknowledged and reinforced when health care professionals tried to introduce insulin to their patients. On the other hand, a negative self-image and fear on insulin injection might cause much emotional distress, which could potentially outweigh their perceived confidence in managing the treatment. Understanding such commonly encountered ambivalent negative emotions and positive cognitions [5] is an essential basic step to build trusting relationships with patients. Training in proper injection techniques and provision of a structured program of face-to-face and telephone support are helpful strategies in initiating insulin in the primary are setting [12]. Involvement of a multidisciplinary health care team, provision of equipment for injection, and home sugar monitoring appear to be essential elements for the successful initiation of insulin in primary care setting [19].

As with many other studies, fear of pain and needles was an important barrier to starting insulin [9, 10] especially in women [8, 20]. Patients with a needle phobia would typically want to avoid medical treatments involving needles [20]. This finding was consistent to patients’ avoidance of insulin injection despite their poor glycemic control. Health care professionals can consider different interventions to overcome needle phobia, such as use of different injection devices or injection sites,[19, 21] and specific counselling to overcome needle phobias [22].

Subjects with lower HbA1c were observed to have greater attitudinal barriers to starting insulin. This seems to be unique to our setting as no such association has been reported in previous studies [8, 10, 23]. Patients may understand their glycemic control as “better” or “acceptable” evidenced by lower HbA1c level. This finding could possibly be explained by previous study finding that the refusal of insulin was caused by patients did not see the necessity for insulin and they actively seek ways to control blood sugar within insulin [5]. Patients may perceive insulin as the last resorts [24]. Subjects in this study had recent HbA1c levels >7.5 %, which signified poor control yet, they may not have perceived that their DM control was sufficiently poor to require insulin. Such disagreements between patient perceptions of glycemic control with the actual HbA1c level may need to be addressed during patient education process. Patient empowerment programs involving self-awareness of treatment target and control level may be helpful to define the best time to starting insulin [25, 26].

Subjects using more types of OADs were found to have significantly higher scores in the subscale related to promoting self-efficacy, which was a positive factor for starting insulin. Adding more types of OADs may be one of the acceptable ways to control blood sugar without insulin. Yet, more types of OADs will raise the patients’ awareness of poor glycemic control. They may possibly be better mentally prepared to accept insulin therapy. Health care professionals can target the patients on multiple OADs for insulin education program.

There were several limitations in this study. The questionnaires were interviewer-administered in majority of the subjects as our patient population has poor literacy levels. It is possible that the Ch-ASIQ score may differ if self-administered. The observed correlation might not be applicable to other cultural or age group patients because all subjects were Chinese in primary care outpatient clinics and most of them were older adults. The resulting score were asked attitude to insulin initiation by cross sectional survey, which might not reflect actual patient refusal behavior when physicians prescribed insulin to them.

Conclusion

In summary, the most significant barriers to commencement of insulin in poorly controlled Type 2 DM Chinese primary care patients appears to be fear of pain and needles. However, most patients are aware of the clinical effectiveness of insulin and have sufficient confidence to learn the skill of insulin injection and how to manage their diet when taking insulin. Women and subjects with lower HbA1c had more negative attitude towards starting insulin. Women had higher fear of pain or needles. Subjects on more types of OADs may be more ready to receive new DM treatment information. To better address conflicting attitudes towards insulin, health care professionals can offer tailored education, which has been shown to be beneficial to poorly controlled DM patients to specifically address the negative attitudes identified in this study.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

Albumin-to-creatinine ratio

- Ch-ASIQ:

-

Chinese attitudes to starting insulin questionnaire

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- eGFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- GOPCs:

-

General outpatient clinics

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- LDL:

-

low density lipoprotein

- OADs:

-

Oral anti-diabetes treatment

- PIR:

-

Psychological insulin resistance

- RAMP:

-

Risk factor assessment & management programme

- RAs:

-

Research assistants

References

American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S14–80.

Brown JB, Nichols GA, Perry A. The burden of treatment failure in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1535–40.

Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, Kvasz M, Tennis P. Delayed initiation of subcutaneous insulin therapy after failure of oral glucose-lowering agents in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a population-based analysis in the UK. Diabetic Med. 2007;24:1412–8.

Hsu WC. Consequences of delaying progression to optimal therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving glycemic goals. South Med J. 2009;102:67–76.

Wang H, Yeh MC. Psychological resistance to insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes: mixed method systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:743–57.

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, Villa-Caballero L, Edelman SV. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2543–5.

Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Jacober SJ, Grunberger G, et al. The influence of treatment modality and ethnicity on attitudes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:313–8.

Nam S, Chesla C, Stotts NA, Kroon L, Janson SL. Factors associated with psychological insulin resistance in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1747–9.

Ho EY, Ho EY, James J. Cultural barriers to initiating insulin therapy in Chinese people with type 2 diabetes living in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2006;30:390–6.

Wong S, Lee J, Ko Y, Chong MF, Lam CK, Tang WE. Perceptions of insulin therapy amongst Asian patients with diabetes in Singapore. Diabetic Med. 2011;28:206–11.

Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:311–21.

Jenkins N, Hallowell N, Farmer AJ, Holman RR, Lawton J. Participants experiences of intensifying insulin therapy during the Treating to Target in Type 2 Diabetes (4-T) trial: qualitative interview study. Diabet Med. 2011;28:543–8.

Fu SN, Chin WY, Wong CK, Yeung VT, Yiu MP, Tsui HY, et al. Development and validation of the Chinese attitudes to starting insulin questionnaire (Ch-ASIQ) for primary care patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):1–9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078933.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–53.

Fung CS, Chin WY, Dai DS, Kwok RL, Tsui EL, Wan YF, et al. Evaluation of the quality of care of a multi-disciplinary risk factor assessment and management programme (RAMP) for diabetic patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:116.

Jiao FF, Fung CSC, Wong CKH, Wan YF, Dai D, Kwok R, et al. Effects of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management program for patients with diabetes mellitus ( RAMP- DM) on biomedical outcomes, observed cardiovascular events and cardiovascular risks in primary care: A longitudinal comparative study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:127.

Wong KW, Ho SY, Chao DV. Quality of diabetes care in public primary care clinics in Hong Kong. Fam Pract. 2012;29:196–202.

Hunt LM, Valenzuela MA, Pugh JA. NIDDM patients’ fears and hopes about insulin therapy. The basis of patient reluctance. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:292–8.

Harris S, Yale JF, Dempsey E, Gerstein H. Can family physicians help patients initiate basal insulin therapy successfully?: randomized trial of patient-titrated insulin glargine compared with standard oral therapy: lessons for family practice from the Canadian INSIGHT trial. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:550–8.

Wright S, Yelland M, Heathcote K, Ng SK, Wright G. Fear of needles--nature and prevalence in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38:172–6.

Iwanaga M, Kamoi K. Patient perceptions of injection pain and anxiety: a comparison of NovoFine 32-gauge tip 6 mm and Micro Fine Plus 31-gauge 5 mm needles. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:81–6.

Sokolowski CJ, Giovannitti Jr JA, Boynes SG. Needle phobia: etiology, adverse consequences, and patient management. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:731–44.

Woudenberg YJ, Lucas C, Latour C, op Reimer WJ S. Acceptance of insulin therapy: a long shot? Psychological insulin resistance in primary care. Diabet Med. 2012;29:796–802.

Tan AM, Muthusamy L, Ng CC, Phoon KY, Ow JH, Tan NC. Initiation of insulin for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: what are the issues? A qualitative study. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:801–9.

Wong CKH, Wong WCW, Wan YF, Chan AKC, Chung KL, Chan FWK, et al. Patient Empowerment Programme in primary care reduced all-cause mortality and cardiovascular diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A population-based propensity-matched cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:128–35.

Wong CK, Wong WC, Lam CL, Wan YF, Wong WH, Chung KL, et al. Effects of Patient Empowerment Programme (PEP) on clinical outcomes and health service utilization in type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: an observational matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95328.

Acknowledgements

The study could not have been completed without the support from all nursing staff, family physicians, and consultants (Special Thanks to Dr. Yiu Yuk Kwan, Chief of Service) of the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority.

Funding source

The project is funded by the Health and Medical Research Fund, Food and Health Bureau, the government of Hong Kong S.A.R. (Reference number 10112261) since Oct 2012. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SF, WC, CW and WL designed the study protocols and the study questionnaire. SF and WL coordinated and supervised data collections in research sites. CW designed and performed statistical analysis and drafted all result tables. SF, CW and WC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, S.N., Wong, C.K.H., Chin, W.Y. et al. Association of more negative attitude towards commencing insulin with lower glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level: a survey on insulin-naïve type 2 diabetes mellitus Chinese patients. J Diabetes Metab Disord 15, 3 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-016-0223-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-016-0223-0