Abstract

Epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a physiological process necessary to normal embryologic development. However in genesis of pathological situations, this transition can be perverted and signaling pathways have different regulations from those of normal physiology. In cancer invasion, such a mechanism leads to generation of circulating tumor cells. Epithelial cancer cells become motile mesenchymal cells able to shed from the primary tumor and enter in the blood circulation. This is the major part of the invasive way of cancer. EMT is also implicated in chronic diseases like fibrosis and particularly renal fibrosis. In adult organisms, healing is based on EMT which is beneficial to repair wounds even if it can sometimes exceed its goal and elicit fibrosis. In this review, we delineate the clinical significance of EMT in both physiological and pathological circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epithelial tissues are the basis of most complex organs. Apical-basal polarity, cell-cell junctions allow tight physical coupling and enable epithelial cells to form sheet structures of generally crystalline order [1,2]. Epithelial sheets can actively migrate during physiological or pathological processes: embryogenesis, wound healing and cancer development. Over the course of these events, individual mesenchymal cells undergo a dispersion supported by an epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT drives cells between two opposite flexible states: epithelial or mesenchymal. Such bold phenotypes are not an absolute rule. Rather than being all-or-nothing EMT is a fine-tuned manner regulated transition for each individual cancer cells. If EMT is a pathological phenomenon in cancer, its embryonic mirror picture will lead to organogenesis, necessary to living beings development. Moreover EMT occurs during the wound healing process. The latter leads when deregulated to fibrosis. In this review we will consider EMT through embryogenesis, in pathological situations like wound healing, fibrosis and finally in oncologic relapses and metastasis. We shall underline what could be the role of EMT in clinical applications.

Review

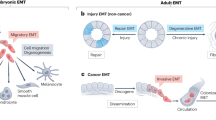

EMT appears to occur in developmental steps during neural crest formation, gastrulation in the primitive streak somite decondensation, cardiac valve formation and other embryological events [3]. Common signaling pathways lead to delamination and migration of epithelial cells. EMT throughout embryogenesis highlights and provides important clues to explain abnormal development or loss of the differentiated state. Many signaling proteins and transcription factors are involved in EMT. Epithelia layered on extracellular matrix (ECM) are separated from it by basal membrane. Their cells have an apical-basal polarity and they are linked together by junctions. The latter are made of specific proteins which build adherens junctions and desmosomes. At the top lateral zones, tight junctions provide sealed connexions. Cells are also related one to another by gap junctions which furthermore support metabolism exchanges [4]. E-cadherin is a typical cadherin implicated in cell adherens junctions. Cadherins are linked to the cortical actin cytoskeleton via catenins. Desmosomes contribute to adhesion. Their structure includes cadherins, desmocollins and desmogleins which interact with cytokeratins through plakoglobulin and plakophilins. Integrins of hemidesmosomes account for basal adhesion [5-7]. The EMT event is characterized by up or down regulation of many proteins that support the epithelial architecture. The regulation is dependent on a web of chemical pathways specific to the type of EMT and tissues. EMT can be classified according to the circumstances of its occurrence. In embryology the phenomenon is called Type 1 EMT [8]. In the context of cancer, EMT is subverted and termed Type 3 EMT. Type 2 EMT leads to generation of new fibroblasts particularly in the field of renal injury [9].

EMT and embryogenesis

EMT is a normal process necessary to development of the body plan: histogenesis and organogenesis. It was known from embryologists studies as soon as 1879 [10] and its revival was highlighted by publications of Greenburg and Hay [11,12]. Gastrulation, a reorganization of single layed embryo into three layers formation was first described by Trelstad et al. They described this phenomenon in chick embryo [13]. From these results, there were exponential publications on this topic.

From this pioneer work many research developments were led on role of EMT in gastrulation, heart formation (including endothelial mesenchymal transition), neural crest. They were realized by using different animal models: drosophila, sea urchin, chicken and mouse embryos. One the best embryological example of EMT is described in mouse embryo gastrulation. The latter is characterized by down regulation of E-cadherin. This protein is controlled at the transcriptional level by Snail1 and at posttranscriptional level by P38 interacting protein [14-16]. Among typical events of EMT, like involution (partial EMT), ingression is a process that allows single cells to delaminate and migrate into the sub-epiblast territory. At the cellular level, it can be explained by a cascade of biochemical reactions. When a cell with intact junctional complexes and epithelial polarity is submitted to EMT, growth factors activate membrane receptors in such a manner that actin cytoskeleton is remodeled and apical-basal polarity lost. Then DDR1 complex is able to activate RhoE resulting in actomyosin contractility weakness [17]. Non canonical pathways are triggered by tight junctions TGFβ receptors leading to ubiquitynilation and degradation of RhoA that destabilize cortical actin microfilaments. Then activation of Snail and Serpent, among transcriptional repressors down regulates genes encoding for E-cadherin, claudin and occludin [18-20]. In addition Srp represses Crb apical polarity gene leading to redistribution of E-cadherin and Snail represses Crumbs3. Zeb1, Crumbs3 and Lgl2 interact. Total EMT can be executed by Snail even through the activation of matrix metalloproteinases. SNAI1 and SNAI2 are key inducers of EMT in gastrulating mouse [21]. Snail1 is prevalent on Snail2 as deletion of Snail2 in mice shows no EMT failure [22]. Schemes describing signaling pathways of EMT can be found in the major publication of Lim and Thierry [23]. EMT failure can be involved in embryological pathology. In this way, EMT seems to be implicated in cleft palate defect. The latter is one of the most common human congenital anomalies affecting around one case in 500–2500 live births. During palatal fusion, the midline epithelial seam between the palatal shelves degrades to achieve mesenchymal confluence. Fusion of the two palate shelves is a process involving cell death, adhesion and EMT. It implies EMT as a regulator of palatal fusion. The main inductor of this transition is TGFβ3 able to activate key EMT transcription factors like Lef1, Twist and Snail1. To support this hypothesis it was demonstrated that TGFβ3 null mice develop cleft palate [24]. Among other embryological pathologies issue from EMT deregulation, congenital heart defects can be suspected. Valvuloseptal endocardial cushion tissue arises from endothelial cells through a phenomenon called endothelial mesenchymal transition. The latter is mainly regulated by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), TGFβ and mesenchymal status (EMT) that are essential area of medical research [25].

Wound healing and EMT

EMT has a major role in wound healing and can explain some of its pathological aspects. EMT is mediated by inflammatory cells and fibroblasts. These cells secrete inflammatory molecules able to interact with proteins of ECM like collagens, laminins, elastin, and tenacins. [26]. Tissue wound healing evolves in three phases: inflammatory, proliferative and maturation phases. The aim of inflammation is to limit tissue damage through phagocytosis. The second phase leads to formation of granulation tissue, angiogenesis, deposition of new ECM and then re-epithelialization. The key step of wound healing is re-epithelialization. Keratinocytes become actively moving cells from the edges to the hole of the wound. Normally the epithelial layer of keratinocytes goes through differentiation of progenitor cells until cell death. This process causes the formation of the epidermis outer layer (cytokeratin skeleton and lipids mixture). This mechanical and hydration barrier protects the underlying tissue. The re-epithelialization is sustained by conversion of cells from sedentary state to the migratory one. This is due to EMT which is essential for wound repair. This modification of cellular phenotype is clearly profitable opposite to changes that occur in a tumor. Comparison of cancer and re-epithelialization EMT has clinical implications. Effectively it can give rise to conflict between cancer therapy and wound healing [27].

TGFβ is a major cytokine inducing EMT and also has other implications in wound healing. Moreover different growth factors can play a role in the EMT process. They include: hepatocyte growth factor, epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, connective tissue growth factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and fibroblast growth factor [8]. High levels of TGFβ have been detected in granulation tissue from healing thermal burn wounds and correlatively there was high expression of TGFβ receptors in fibroblasts involved in wound repair. The up-regulation of TGFβ can exceed its goal and leads to hypertrophic scars [28].

Osteopontin (OPN), a glycoprotein also named Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 has been implicated in 3 types (EMT associated with migration of cancer cells (metastasis) is referred as Type III. EMT process ongoing in embryogenesis is named Type I and Type II is linked to regeneration/fibrosis). OPN is able to bind different integrin receptors and several transcription factors regulated by TGFβ sustain the expression of OPN. Thus, OPN seems to play a central role in TGFβ-dependent processes and is involved in TGFβ dependent EMT [29].

Fibrosis and EMT

The best fibrosis model depicted in clinical pathology is renal interstitial fibrosis. It is a progressive and lethal disease due to different grounds like urinary tract obstruction, chronic inflammation and diabetes [30]. EMT plays a key role in the development of renal tubular fibrosis and synthesis of extracellular matrix. Pathways of this pathological EMT are studied by numerous laboratories as new therapies could target it and be opposed to its progression. TGFβ upstream regulates many pathways. Among them are included Smad as well as MAPK-PI3k signaling pathways, TGFβ receptor kinase phosphorylates Smad 2 and 3. The activated latter interact with Smad4 that undergoes nucleus translocation, thus regulating transcription TGFβ target genes. TGFβ/Smad3 regulation seems to be essential in pathological fibroses [31].

Renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis leads to end-stage renal failure [32]. This process associates ECM deposition, inflammatory cells infiltration, fibroblasts accumulation with loss of tubular epithelial cells. The pathology is sustained by EMT targeting tubular cells. The latter acquire the classical markers of this pathway. The major growth factor driving the transformation is TGFβ. The reversion of EMT reduces fibroblasts proliferation and deposition of ECM in the cortical interstitium. Thus, the best choice to prevent progressive renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis is to regulate EMT [33]. Activation of hedgehog signaling that induces TGFβ expression has profibrogenic effects [34]. This pathway is activated by binding of the ligands including sonic hedgehog (Shh) to its membrane receptor patched 1 (Ptch1). Transduction by Smoothened (Smo), leads to translocation of the transcription factor Gli1 to the nucleus. This activation of hedgehog induces fibrogenesis. EMT in renal fibrosis has been debated [35-37]. Inoue et al. demonstrated that disease models and murine strains used in experimental conditions have to be taken into account to explain reported discrepancies [38]. Finally in a review, Galichon and Hertig showed the role of EMT markers in the diagnosis and prognosis of kidney failures [39]. They indicated that among EMT markers used in immunohistochemistry, the best could be simultaneously vimentin and β-catenin. At the opposite they excluded the fibroblast-specific protein (FSP1) and E-cadherin. They reported their study on renal allograft: three months after transplantation, vimentin and β-catenin had prognostic value and were associated with a more rapid progression towards graft interstitial fibrosis and decrease in renal function at twelve months. This paper is a proof that EMT research can be translated to clinical applications [40].

Recent publications of Leask et al. demonstrated that TGFβ is able to promote tissue repair and fibrosis trough the noncanonical focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway. FAK is implicated in myofibroblast differentiation. Thus acting on FAK pathway could be a major point to treat fibrosis disease. In a similar way excessive scarring could benefit from the same drugs [41,42].

Cancer and EMT

The major headline of EMT in clinical application is related to cancer disease. Effectively there is a close link between EMT, circulating tumor cells (CTC) and metastasis. EMT endows tumor cells with new features, chemo and radiotherapy resistances. Thus, EMT is a major target to break the deleterious cycle of cancer. From the primary tumor, some epithelial cells can lose their cell-cell adhesion and become motile and invasive mesenchymal cells. These cells invade the ECM and migrate along a newly formed matrix of fibronectin and type I collagen [8]. They can move as single cells or be part of a collective migration: cell clusters. The latter made of cells with mixed phenotype (epithelial-mesenchymal) can avoid anoikis and lead more easily than single cells to metastasis [43]. Thus these results suggest that mesenchymal cells can protect from anoikis epithelial cells included in a cluster. Shed cells cross the ECM to reach vessels (intravasation) and by extravasation they colonize a distant organ in a specific niche. Then they stay as dormant tumor cells, micrometastasis or grow as a macrometastasis. The fate of such a new localization is depending on the mesenchymal epithelial transition (MET) which is the reverse way of EMT. We will review the different steps of this phenomenon.

From an epithelial tumor, cancer cells can reach vessels leading to CTCs. Many factors induce shedding of cancer cells. Transcription factors acting on gene expression are able to promote loss of cell-cell adhesions. As a result there is a shift in cytoskeletal anatomy and a change from epithelial morphology to the mesenchymal one. The EMT switch is on a signaling pathway dependence of TGFβ, BMP, Wnt–β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, and receptor tyrosine kinases. Many studies reported the role of several micro RNAs in the regulation of EMT and their interactions with ZEB1 and ZEB2 [44]. Izumchenko et al. demonstrated that the role of microRNA network on EMT-associated kinase switch [45]. Studies on EMT and micro RNA relations are a hot field now and would deserve a specific review. Moreover abnormal cancer epigenome is also implicated in control of EMT and stemness. Epigenetic deregulation evidently has a role in cancer that can be targeted in clinical trials [46].

The major stimulus able to activate the TGFβ pathway is hypoxia acting through HIF1α. The epithelial cobblestone growth pattern is held together by cell adhesion molecules (claudins and E-cadherin). The basal membrane anchors epithelial cells, through hemidesmosomes, to the ECM and provide their apical-basal polarity. Hallmarks of EMT are decreased expression of E-cadherin, tight junction proteins (ZO-1 and occludin) and cytokeratins while mesenchymal markers are overexpressed (vimentin, N-cadherin). Individual motile and shape spindle cells enter the ECM to reach vessels. This scheme is not as simple as described. Effectively a continuum of transformation from epithelial to mesenchymal cells has been suggested [47]. Moreover in two recent publications Jolly et al. proposed a mathematical model related to the process evolution [48,49]. They described the hybrid phenotype (epithelial and simultaneously mesenchymal) that gains likelihood stemness. This model could define the characteristics of cell clusters which are found among CTCs. Cancer stem cells have particular properties as they have the capacity to both self renew and differentiate into non stem tumor cells. A closed relation between induction of EMT and endowing of stemness characteristic has been demonstrated [46,50,51]. These kinds of hybrid cells seem likely to support micrometastasis and or relapses. In a recent publication, Ilie et al. demonstrated that cluster of hybrid cells are evidenced in the blood of patients with obstructive bronchopathy, at least 3 years before a primary lung tumor can be detected [52]. Aceto et al. demonstrated that CTC clusters are 50 fold more metastatic than single CTCs [43]. All these published results lead to the hypothesis that the major target to avoid relapse and metastasis in cancer are the hybrid phenotype (epithelial and mesenchymal) cells. Another therapeutic opportunity would be to interact on the reversion of EMT: MET. Effectively the major result of EMT is extravasation of CTCs into ectopic organs. After this step, cancer cells must survive in the adverse environment of organ parenchyma. There are new evidences that EMT is not irreversible and that reexpression of adhesion molecules due to MET promote survival and proliferation of cancer cells. One major factor of this reverse process seems to be the transcription factor MYB [53]. Moreover Ocana et al. showed that Twist downregulation favors metastasis formation. However silencing Twist alone is not sufficient to induce metastasis in the presence of PRRX1. PRRX1 loss is sufficient to reverse EMT even in the presence of other EMT inducers such as Twist1. Thus downregulation of PRRX1 leads to MET which goes along with acquisition of stem cell properties and increase of intermediary cell phenotype (epithelioid-mesenchymal) proliferation [54]. Targeting cells having EMT and cancer stem cell features appears a difficult task as normal stem cells share many identical characteristics. However Kreso et al. described a new therapeutic way to downregulate the BMI1-related self renewal without alteration of normal stem cells [55].

Many authors have compared EMT in different pathophysiological conditions. They assess similarities and discrepancies in protein expression and or signaling pathways in cancer and wound healing [56-58]. The CCN protein family interacts with integrins leading to release of growth factors, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. CCN2 and CCN4 are specifically up-regulated during wound healing while CCN3 and CCN5 are down-regulated [59-61]. The spectrum of CCN proteins could be one of the discrepancies between EMT of wound healing and cancer. Effectively, CCN1 and CCN6 have been characterized to have tumor promoting activity [62-64]. Both the Ras/ERK/MAPK pathway [65,66] and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis [67,68] are used in wound healing and cancer EMT. The discrepancy is rather based on transcription factor activity. Thus while Slug activity is upregulated in both wounded epithelium and in tumor cells [69-74], Snail has not been described as a major player during wound healing [75-80]. Moreover Zeb1, Ets-1, and FoxC2 seem to be an hallmark of cancer EMT. As both types of EMT share many similar signaling pathways, it is difficult to develop therapies targeting solely cancer EMT or wound healing EMT.

Conclusion

EMT is a central physiological process for homeostasis and health of live beings. When shapely, fine tuned, during embryo development it leads to a normal anatomical body. The least failure of its regulating pathways sustained embryological defects. In a fully developed organism, when EMT is perverted, its activation is accountable for pathological situations as demonstrated in cancer and fibrosis diseases. EMT is still a beneficial way when acting in repair wounds. Nevertheless if we compared wound healing and cancer growth, we can consider cancer growth as a wound healing process that goes over its aim. Such opposing roles underline the difficulties to develop EMT drugs. Many therapies have been proposed to act on the receptors and/or signaling pathways that give rise to EMT. As mechanisms between cancer EMT and wound healing are shared, a conflict can rise between therapy of cancer and promotion of wound healing [27]. This review underlines the complexity of pharmacological improvements as EMT has conflicting aims according to its role in the targeted pathologies: fibrosis, wound healing, cancers.

Abbreviations

- EMT:

-

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

- MET:

-

Mesenchymal epithelial transition

- CTC:

-

Circulating tumor cell

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix.

References

Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:887–901.

Martin-Belmonte F, Mostov K. Regulation of cell polarity during epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:227–34.

Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re8.

Goodenough DA, Goliger JA, Paul DL. Connexins, connexons, and intercellular communication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:475–502.

Wei Q, Huang H. Insights into the role of cell-cell junctions in physiology and disease. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;306:187–221.

Capaldo CT, Farkas AE, Nusrat A. Epithelial adhesive junctions. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:1.

Brooke MA, Nitoiu D, Kelsell DP. Cell-cell connectivity: desmosomes and disease. J Pathol. 2012;226:158–71.

Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–8.

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90.

Duval M. Atlas d’Embryologie. Paris: Masson; 1879.

Greenburg G, Hay ED. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:333–9.

Hay ED. The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:706–20.

Trelstad RL, Hay ED, Revel JD. Cell contact during early morphogenesis in the chick embryo. Dev Biol. 1967;16:78–106.

Zohn IE, Li Y, Skolnik EY, Anderson KV, Han J, Niswander L. p38 and a p38interacting protein are critical for downregulation of Ecadherin during mouse gastrulation. Cell. 2006;125:957–69.

Lee JD, Silva-Gagliardi NF, Tepass U, McGlade CJ, The AKV, FERM. protein Epb4.1 l5 is required for organization of the neural plate and for the epithelialmesenchymal transition at the primitive streak of the mouse embryo. Development. 2007;134:2007–16.

Hirano M, Hashimoto S, Yonemura S, Sabe H, Aizawa S. EPB41L5 functions to post-transcriptionally regulate cadherin and integrin during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1217–30.

Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Hooper S. Chaudhry S I, Williamson P, Harrington K, Leitinger B and Sahai E: Collective cell migration requires suppression of actomyosin at cell-cell contacts mediated by DDR1 and the cell polarity regulators Par3 and Par6. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:49–58.

Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Wahlbuhl M, Dimmler A, Bauer K, Sultan A. The transcriptional repressor ZEB1 promotes metastasis and loss of cell polarity in cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:537544.

Whiteman EL, Liu CJ, Fearon ER, Margolis B. The transcription factor snail represses Crumbs3 expression and disrupts apico-basal polarity complexes. Oncogene. 2008;27:3875–9.

Campbell K, Whissell G, Franch-Marro X, Batlle E, Casanova J. Specific GATA factors act as conserved inducers of an endodermal-EMT. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1051–61.

Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005;132:3151–61.

Jiang R, Lan Y, Norton CR, Sundberg JP, Gridley T. The Slug gene is not essential for mesoderm or neural crest development in mice. Dev Biol. 1998;198:277–85.

Lim J, Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: insights from Development. Development. 2012;139:3471–86.

Martínez-Alvarez C, Blanco MJ, Pérez R, Rabadán MA, Aparicio M, Resel E, et al. Snail family members and cell survival in physiological and pathological cleft palates. Dev Biol. 2004;265:207–18.

Sakabe M, Matsui H, Sakata H, Ando K, Yamagishi T, Nakajima Y. Understanding heart development and congenital heart defects through developmental biology: a segmental approach. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2005;45:107–18.

Volk SW, Iqbal SA. Bayat A: Interactions of the Extracellular Matrix and Progenitor Cells in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2:261–72.

Leopold PL, Vincent J, Wang H. A comparison of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and re-epithelialization. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:471–83.

Rorison P, Thomlinson A, Hassan Z, Roberts SA, Ferguson MW, Shah M. Longitudinal changes in plasma Transforming growth factor beta-1 and post-burn scarring in children. Burns. 2010;36:89–96.

El-Tanani M, Platt-Higgens A, Rudland PS, Campbell FC. Ets gene PEA3 cooperates with beta-catenin-Lef-1 and c-Jun in regulation of osteopontin transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20794–806.

Border WA, Noble NA. TGF-β in kidney fibrosis: a target for gene therapy. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1388–96.

Roberts AB, Tian F, Byfield SD, Stuelten C, Ooshima A, Saika S, et al. Smad3 is key to TGF-beta-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis, tumor suppression and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:19–27.

Meran S, Steadman R. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in renal fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:158–67.

Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, Mammoto T, Charytan D, Strutz F, et al. BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat Med. 2003;9:964–8.

Syn WK, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Abdelmalek M, Guy CD, Yang L, et al. Hedgehog-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenic repair in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1478–88.

Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:85–97.

Koesters R, Kaissling B, Lehir M, Picard N, Theilig F, Gebhardt R, et al. Tubular overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta1 induces autophagy and fibrosis but not mesenchymal transition of renal epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:632–43.

Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Duffield JS. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–27.

Inoue T, Umezawa A, Takenaka T, Suzuki H, Okada H. The contribution of epithelialmesenchymal transition to renal fibrosis differs among kidney disease models. Kidney Int. 2014;doi:10.1038/ki.2014.235.

Galichon P, Hertig A. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a biomarker in renal fibrosis: are we ready for the bedside? Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2011;4:11.

Hertig A, Anglicheau D, Verine J, Pallet N, Touzot M, Ancel PY, et al. Early Epithelial phenotypic changes predict graft fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1584–91.

Focal LA, Kinase A. A Key Mediator of Transforming Growth Factor Beta Signaling in Fibroblasts. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2:247–9.

Guo F, Carter DE. Leask A: miR-218 regulates focal adhesion kinase-dependent TGFβ signaling in fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1151–8.

Aceto N, Bardia A, Miyamoto DT, Donaldson MC, Wittner BS, Spencer JA, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014;158:1110–22.

Díaz-López A, Moreno-Bueno G, Cano A. Role of microRNA in epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis and clinical perspectives. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:205–16.

Izumchenko E, Chang X, Michailidi C, Kagohara L, Ravi R, Paz K, et al. The TGFβ-miR200-MIG6 pathway orchestrates the EMT-associated kinase switch that induces resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3995–4005. Erratum in. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4950–1.

Czerwinska P, Kaminska B. Regulation of breast cancer stem cell features. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2015;19:A7–15.

Barrière G, Riouallon A, Renaudie J, Tartary M, Rigaud M. Mesenchymal and stemness circulating tumor cells in early breast cancer diagnosis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:114.

Jolly MK, Huang B, Lu M, Mani SA, Levine H, Ben-Jacob E. Towards elucidating the connection between epithelial-mesenchymal transitions and stemness. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20140962.

Lu M, Jolly MK, Levine H, Onuchic JN, Ben-Jacob E. MicroRNA-based regulation of epithelial-hybrid-mesenchymal fate determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:18144–9.

Jung HY, Yang J. Unraveling the TWIST between EMT and cancer stemness. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:1–2.

Abell AN, Johnson GL. Implications of Mesenchymal Cells in Cancer Stem Cell Populations: Relevance to EMT. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2014;2:21–6.

Ilie M, Hofman V, Long-Mira E, Selva E, Vignaud JM, Padovani B, et al. "Sentinel" circulating tumor cells allow early diagnosis of lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111597.

Hugo HJ, Pereira L, Suryadinata R, Drabsch Y, Gonda TJ, Gunasinghe NP, et al. Direct repression of MYB by ZEB1 suppresses proliferation and epithelial gene expression during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R113.

Ocaña OH, Córcoles R, Fabra A, Moreno-Bueno G, Acloque H, Vega S, et al. Metastatic colonization requires the repression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer Prrx1. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:709–24.

Kreso A, van Galen P, Pedley NM, Lima-Fernandes E, Frelin C, Davis T, et al. Arrowsmith CH8, Szentgyorgyi E, Gallinger S, Dick JE, O'Brien CA: Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20:29–36.

Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–96.

Grünert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:657–65.

Weber CE, Li NY, Wai PY, Kuo PC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, TGF-β, and osteopontin in wound healing and tissue remodeling after injury. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:311–8.

Brieher WM, Yap AS. Cadherin junctions and their cytoskeleton(s). Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:39–46.

Hansen SM, Berezin V, Bock E. Signaling mechanisms of neurite outgrowth induced by the cell adhesion molecules NCAM and N-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3809–21.

Cavallaro U, Christofori G. Cell adhesion and signalling by cadherins and Ig-CAMs in cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2004;4:118–32.

Zhang Y, Pan Q, Zhong H, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Inhibition of CCN6 (WISP3) expression promotes neoplastic progression and enhances the effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 on breast epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R1080–9.

Davies SR, Davies ML, Sanders A, Parr C, Torkington J, Jiang WG. Differential expression of the CCN family member WISP-1, WISP-2 and WISP-3 in human colorectal cancer and the prognostic implications. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1129–36.

Haque I, Mehta S, Majumder M, Dhar K, De A, McGregor D, et al. Cyr61/CCN1 signaling is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness and promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:8.

Janda E, Lehmann K, Killisch I, Jechlinger M, Herzig M, Downward J, et al. Ras and TGF[beta] cooperatively regulate epithelial cell plasticity and metastasis: dissection of Ras signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:299–313.

Janda E, Litos G, Grunert S, Downward J, Beug H. Oncogenic Ras/Her-2 mediate hyperproliferation of polarized epithelial cells in 3D cultures and rapid tumor growth via the PI3K pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:5148–59.

Keniry M, Parsons R. The role of PTEN signaling perturbations in cancer and in targeted therapy. Oncogene. 2008;27:5477–85.

Wu T, Mohan C. The AKT axis as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:145–50.

Arnoux V, Nassour M, L’Helgoualćh A, Hipskind RA, Savagner P. Erk5 controls Slug expression and keratinocyte activation during wound healing. Mol Biol Cel. 2008;19:4738–49.

Shirley SH, Hudson LG, He J, Kusewitt DF. The skinny on Slug. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2010;49:851–61.

Savagner P, Yamada KM, Thiery JP. The zinc-finger protein slug causes desmosome dissociation, an initial and necessary step for growth factor-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1403–19.

Savagner P, Kusewitt DF, Carver EA, Magnino F, Choi C, Gridley T, et al. Developmental transcription factor slug is required for effective re-epithelialization by adult keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:858–66.

Kusewitt DF, Choi C, Newkirk KM, Leroy P, Li Y, Chavez MG, et al. Slug/Snai2 is a downstream mediator of epidermal growth factor receptor-stimulated reepithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:491–5.

Hudson LG, Newkirk KM, Chandler HL, Choi C, Fossey SL, Parent AE, et al. Cutaneous wound reepithelialization is compromised in mice lacking functional Slug (Snai2). J Dermatol Sci. 2009;56:19–26.

Sou PW, Delic NC, Halliday GM, Lyons JG. Snail transcription factors in keratinocytes: enough to make your skin crawl. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1940–4.

Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial–mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83.

Guaita S, Puig I, Franci C, Garrido M, Dominguez D, Batlle E, et al. Snail induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in tumor cells is accompanied by MUC1 repression and ZEB1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39209–16.

Olmeda D, Jorda M, Peinado H, Fabra A, Cano A. Snail silencing effectively suppresses tumour growth and invasiveness. Oncogene. 2007;26:1862–74.

Medici D, Hay ED, Olsen BR. Snail and Slug promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition through beta-catenin-T-cell factor-4-dependent expression of transforming growth factor-beta3. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4875–87.

Vincent T, Neve EP, Johnson JR, Kukalev A, Rojo F, Albanell J, et al. A SNAIL1-SMAD3/4 transcriptional repressor complex promotes TGF-beta mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:943–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

Equal contribution of each author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barriere, G., Fici, P., Gallerani, G. et al. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition: a double-edged sword. Clin Trans Med 4, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-015-0055-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-015-0055-4